Validating Biosynthetic Pathways: From Computational Prediction to Experimental Confirmation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating biosynthetic pathways, essential for researchers and drug development professionals working with natural products.

Validating Biosynthetic Pathways: From Computational Prediction to Experimental Confirmation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating biosynthetic pathways, essential for researchers and drug development professionals working with natural products. It covers foundational concepts in pathway discovery, explores cutting-edge computational and experimental methodologies, addresses troubleshooting and optimization challenges, and establishes rigorous validation standards. By integrating multi-omics data, artificial intelligence, and synthetic biology approaches, this guide bridges the gap between in silico predictions and functionally confirmed pathways, accelerating the development of bioactive compounds for biomedical applications.

Laying the Groundwork: Principles of Biosynthetic Pathway Discovery

Plant specialized metabolites, historically known as secondary metabolites, represent one of nature's most formidable reservoirs of chemical diversity. With an estimated 200,000 to 1,000,000 distinct compounds across the plant kingdom, these metabolites are essential for plant adaptation, defense, and interaction with the environment [1] [2]. Unlike primary metabolites, which are conserved and vital for growth, the biosynthesis of specialized metabolites is often species-, organ-, and tissue-specific, and dynamically regulated by developmental and environmental cues [1] [3]. This immense diversity, however, presents a significant scientific challenge: the vast majority of biosynthetic pathways for these therapeutically valuable compounds remain partially or completely unknown. This guide objectively compares the performance of modern experimental and computational methodologies dedicated to elucidating these elusive pathways, providing a framework for researchers to validate biosynthetic functionality.

Comparative Analysis of Pathway Elucidation Strategies

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, outputs, and validation requirements of the primary methodologies used in pathway discovery.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Pathway Elucidation Methodologies

| Methodology | Key Output | Typical Experimental Validation Required? | Spatial Resolution | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| In vitro Culture & Elicitation [4] | Enhanced metabolite yield; precursor relationships | Yes, for pathway confirmation | Bulk tissue (Low) | Culture instability; yield not always predictive of native pathway |

| Spatial Mass Spectrometry Imaging [2] | Spatial distribution maps of metabolites | Yes, for compound identity and function | Tissue to single-cell (High) | Limited sensitivity for low-abundance metabolites |

| Computational Pathway Simulation [5] | Predicted metabolite flux changes; candidate enzyme impacts | Yes, for model predictions | Not applicable | Model accuracy dependent on prior knowledge and parameters |

| Over-representation Analysis (ORA) [6] | Statistically enriched pathways from a metabolite list | Yes, for functional validation | Bulk tissue (Low) | Highly sensitive to background set and database choice |

Detailed Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol for Computational Pathway Prediction and Validation

Computational models simulate metabolic networks to predict how genetic variations or perturbations influence metabolite concentrations, providing testable hypotheses for experimental biology [5].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for Computational & ORA Studies

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Curated Metabolic Pathway Model (e.g., from BioModels) [5] | Provides the computational framework of biochemical reactions, metabolites, and enzymes. |

| Organism-Specific Pathway Database (KEGG, Reactome) [6] | Defines the set of known pathways and metabolites for enrichment analysis. |

| Assay-Specific Background Metabolite Set [6] | Serves as the reference list in ORA to prevent false-positive pathway enrichment. |

| Enzyme Reaction Rate Parameters [5] | Basal kinetic constants are systematically adjusted in silico to simulate genetic variants. |

Workflow Description: The process begins with a curated metabolic model. Enzyme reaction rates are systematically perturbed to simulate the effect of genetic variations, and differential equations are solved to predict changes in metabolite concentrations. These predictions are compared against empirical data from techniques like mGWAS to validate and refine the model, prioritizing variant-metabolite pairs for experimental investigation [5].

Protocol for Spatial Mapping of Specialized Metabolites

Spatial metabolomics technologies like MALDI-MSI and DESI-MSI are critical for correlating metabolite accumulation with specific tissues or cell types, providing essential clues about pathway activity location [2].

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Spatial Metabolomics

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Matrix (e.g., CHCA, DHB) for MALDI-MSI [2] | Embeds the tissue section to absorb laser energy and desorb/ionize metabolites. |

| Cryostat or Microtome [2] | Prepates thin, consistent tissue sections (5-20 µm) for imaging analysis. |

| High-Resolution Mass Spectrometer (e.g., TOF, Orbitrap) [2] | Analyzes the mass-to-charge ratio of ionized metabolites with high accuracy. |

| Spectral Library & Imaging Software [2] [7] | Annotates detected features and maps their spatial distribution. |

Workflow Description: A plant tissue sample is first harvested and flash-frozen to preserve its metabolic state. It is then sectioned into thin slices and mounted on a target plate. For MALDI-MSI, a matrix is applied to the section to facilitate desorption and ionization. The plate is rasterized under a laser or ion beam, and a mass spectrum is acquired for each pixel, generating a hyperspectral dataset. Specialized software is used to reconstruct the spatial distribution of hundreds to thousands of metabolites across the tissue [2].

Protocol for Functional Validation Using In Vitro Cultures

Plant cell, tissue, and organ cultures (PCTOC) provide a controlled system to manipulate and validate pathway functionality through elicitation and metabolic engineering [4].

Workflow Description: The process begins with establishing an in vitro culture system, such as a hairy root or cell suspension culture, from the medicinal plant of interest. These cultures are then treated with biotic or abiotic elicitors (e.g., jasmonic acid, UV light, or fungal extracts) to trigger a defense response and stimulate the biosynthesis of target specialized metabolites. The metabolic response is profiled using techniques like LC-MS/MS or GC-MS. This data is used to compute metabolic flux and identify key pathway nodes, which can be further validated through metabolic engineering or enzyme assays [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key materials and their functions for conducting research in this field, as derived from the cited experimental protocols.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Pathway Elucidation

| Research Reagent / Solution | Function in Pathway Research |

|---|---|

| Hairy Root or Cell Suspension Cultures [4] | Provides a genetically stable, controllable, and scalable system for producing specialized metabolites and testing pathway function. |

| Elicitors (e.g., Methyl Jasmonate, Chitosan) [4] [3] | Used to perturb biosynthetic pathways, induce defense responses, and study the upregulation of pathway genes and metabolites. |

| LC-MS/MS with High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry [4] [7] | The core analytical platform for sensitive identification and quantification of a wide range of specialized metabolites in complex extracts. |

| KEGG, Reactome, MetaCyc Pathway Databases [6] | Provide the reference knowledge of curated biochemical reactions and pathways essential for ORA and computational modeling. |

| MetaboAnalyst Software Platform [7] | A comprehensive web-based tool for performing statistical, pathway, and enrichment analysis on metabolomics data. |

No single methodology can fully resolve the complex biosynthetic pathways of plant specialized metabolites. Computational ORA and modeling are powerful for generating hypotheses but are contingent on database quality and require experimental cross-validation [6] [5]. Spatial metabolomics provides unparalleled insight into the localization of pathway products but often lacks the sensitivity to detect all intermediates [2]. Functional validation in in vitro cultures remains the gold standard for confirming pathway activity, though it can be hampered by low yields and the disconnect from the native plant environment [4]. The path forward lies in a multi-omics, integrated approach, where computational predictions guide spatial and functional experiments, and experimental results, in turn, refine computational models. This synergistic strategy is key to systematically illuminating the vast, dark matter of plant specialized metabolism and unlocking its potential for drug discovery and development.

Elucidating complete biosynthetic pathways represents a significant bottleneck in metabolic research, particularly for the vast "dark matter" of uncharacterized plant specialized metabolites [8]. While individual omics technologies provide valuable snapshots of biological systems, they offer limited insights when used in isolation. Transcriptomics measures RNA expression as an indirect measure of DNA activity, proteomics identifies and quantifies the functional protein products, and metabolomics focuses on the ultimate mediators of metabolic processes—the small molecule metabolites [9]. Multi-omics integration has emerged as a powerful solution, providing a comprehensive view of biological systems by combining these complementary data layers to uncover complex patterns and interactions that remain invisible in single-omics analyses [9] [10]. This approach is particularly valuable for validating biosynthetic pathway functionality, as it allows researchers to connect gene expression with subsequent metabolic products through known reaction rules and correlation patterns [8]. By simultaneously analyzing multiple molecular layers, scientists can achieve deeper insights into molecular mechanisms, identify novel biomarkers, and uncover therapeutic targets with greater confidence than previously possible [9].

Comparative Analysis of Multi-Omics Integration Methodologies

Classification of Integration Strategies

Multi-omics data integration strategies can be broadly categorized into three main approaches: combined omics integration, correlation-based strategies, and machine learning integrative approaches [9]. Combined omics integration explains what occurs within each type of omics data in an integrated manner, generating independent datasets. Correlation-based strategies apply statistical correlations between different omics datasets to create network structures representing these relationships. Machine learning approaches utilize one or more types of omics data to comprehensively understand responses at classification and regression levels, particularly in relation to diseases [9].

More technically, these strategies can be further broken down into five distinct frameworks: early, mixed, intermediate, late, and hierarchical integration [11]. Early integration concatenates all omics datasets into a single matrix for machine learning application. Mixed integration first independently transforms each omics block into a new representation before combining them. Intermediate integration simultaneously transforms original datasets into common and omics-specific representations. Late integration analyzes each omics separately and combines their final predictions. Hierarchical integration bases dataset integration on prior regulatory relationships between omics layers, following biological principles such as the central dogma of molecular biology [11].

Table 1: Classification of Multi-Omics Integration Approaches

| Integration Strategy | Key Principle | Best Use Cases | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early Integration | Direct concatenation of all omics data into single matrix | Small datasets with minimal noise; when feature relationships are straightforward | Prone to overfitting with high-dimensional data; requires careful feature selection |

| Intermediate Integration | Simultaneous transformation to find common representations | Identifying cross-omics patterns; data with complementary information | Computationally intensive; requires specialized algorithms (e.g., MOFA, iCluster) |

| Late Integration | Separate analysis with prediction fusion | Heterogeneous data types; when omics have different statistical properties | Preserves data-specific characteristics; may miss subtle cross-omics interactions |

| Hierarchical Integration | Based on known biological hierarchies (e.g., central dogma) | Pathway elucidation; causal inference studies | Requires prior biological knowledge; excellent for mechanistic insights |

| Correlation-Based | Statistical correlations between omics layers | Gene-metabolite network construction; hypothesis generation | Can identify spurious correlations; requires large sample sizes for robustness |

Performance Benchmarking of Integration Methods

Comprehensive evaluations of multi-omics integration methods have revealed critical insights for practical implementation. Contrary to intuitive expectations, incorporating more omics data types does not always improve predictive performance and can sometimes degrade results due to the introduction of noise and redundant information [12] [13]. A large-scale benchmark study evaluating 31 possible combinations of five omics data types (mRNA, miRNA, methylation, DNAseq, and CNV) across 14 cancer datasets found that using only mRNA data or a combination of mRNA and miRNA data was sufficient for most cancer types [13]. For some specific cancers, the additional inclusion of methylation data improved predictions, but generally, introducing more data types resulted in performance decline.

The Quartet Project has provided groundbreaking resources for objective multi-omics method evaluation by developing reference materials from immortalized cell lines of a family quartet (parents and monozygotic twin daughters) [10]. This approach provides "built-in truth" defined by both the genetic relationships among family members and the information flow from DNA to RNA to protein, enabling rigorous quality control and method validation. Their research identified reference-free "absolute" feature quantification as the root cause of irreproducibility in multi-omics measurement and established the advantages of ratio-based profiling that scales absolute feature values of study samples relative to a concurrently measured common reference sample [10].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Multi-Omics Data Combinations in Survival Prediction

| Data Combination | Average Performance (C-index) | Clinical Utility | Implementation Complexity |

|---|---|---|---|

| mRNA only | 0.745 | Sufficient for most cancer types | Low |

| mRNA + miRNA | 0.751 | Best balance for general use | Moderate |

| mRNA + miRNA + Methylation | 0.749 | Beneficial for specific cancers | High |

| All five omics types | 0.732 | Suboptimal despite comprehensive data | Very High |

Experimental Protocols for Multi-Omics Pathway Elucidation

Workflow for Integrated Pathway Analysis

A standardized workflow for multi-omics pathway elucidation begins with experimental design and sample preparation, where consistent handling across all omics platforms is critical [10]. For transcriptomics, RNA sequencing is performed using platforms such as DNBSEQ-T7 with quality control measures including RIN scores and alignment rates [14]. Metabolomics analysis typically employs ultra-performance liquid chromatography coupled with tandem mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS/MS) with extraction in 70% methanol containing internal standards [14]. Data preprocessing includes quality filtering, normalization, and feature identification against standardized databases [14].

Integration proceeds through correlation analysis, typically using Mutual Rank-based correlation to maximize highly correlated metabolite-transcript associations while minimizing false positives [8]. Bioinformatics tools then leverage reaction rules and metabolic structures from databases like RetroRules and LOTUS to assess whether observed chemical differences between metabolites can be logically explained by reactions catalyzed by transcript-associated enzyme families [8]. Joint-Pathway Analysis and interaction databases like STITCH further reveal altered pathway networking [15]. Validation steps include qRT-PCR for gene expression confirmation and independent cohort testing [14].

Specialized Tools for Multi-Omics Integration

Several specialized computational tools have been developed specifically for multi-omics integration in pathway elucidation. MEANtools represents a significant advancement as a systematic and unsupervised computational workflow that predicts candidate metabolic pathways de novo by leveraging reaction rules and metabolic structures from public databases [8]. It uses mutual rank-based correlation to capture mass features highly correlated with biosynthetic genes and assesses whether observed chemical differences between metabolites can be explained by reactions catalyzed by transcript-associated protein families [8].

Other approaches include Similarity Network Fusion (SNF), which builds similarity networks for each omics data type separately before merging them to highlight edges with high associations across omics networks [9]. Weighted Correlation Network Analysis (WGCNA) identifies co-expressed gene modules and correlates them with metabolite abundance patterns to identify metabolic pathways co-regulated with specific gene modules [9]. For plant specialized metabolism, tools like plantiSMASH, PhytoClust, and PlantClusterFinder identify gene clusters likely to encode enzymes associated with specialized metabolite pathways [8].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Multi-Omics Pathway Studies

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Example Application | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Quartet Reference Materials | Multi-omics ground truth for QC | Method validation across platforms | Enables ratio-based profiling [10] |

| LOTUS Database | Natural product structure resource | Metabolite annotation | Comprehensive well-annotated resource [8] |

| RetroRules Database | Enzymatic reaction rules | Predicting putative reactions | Includes known and predicted protein domains [8] |

| String Database | Protein-protein interactions | Network construction | Maps proteins to functional associations [14] |

| KEGG Pathway Database | Pathway mapping | Functional annotation | Essential for pathway enrichment analysis [15] |

Case Studies in Pathway Elucidation

Radiation Response Pathways

A pioneering multi-omics study investigating radiation-induced altered pathway networking demonstrated the power of integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics in uncovering complex biological responses [15]. Researchers exposed murine models to 1 Gy and 7.5 Gy of total-body irradiation and analyzed blood samples at 24 hours post-exposure. Transcriptomic profiling revealed differential expression of 2,837 genes in the high-dose group, with Gene Ontology-based enrichment analysis showing significant perturbation in pathways associated with immune response, cell adhesion, and receptor activity [15].

Integrated analysis identified 16 metabolic enzyme genes that were dysregulated following radiation exposure, including genes involved in lipid, nucleotide, amino acid, and carbohydrate metabolism such as Aadac, Abat, Aldh1a2, and Hmox1 [15]. Joint-Pathway Analysis and STITCH interaction mapping revealed that radiation exposure resulted in significant changes in amino acid, carbohydrate, lipid, nucleotide, and fatty acid metabolism, with BioPAN predicting specific fatty acid pathway enzymes including Elovl5, Elovl6 and Fads2 only in the high-dose group [15]. This comprehensive approach provided unprecedented insights into the metabolic consequences of radiation exposure, demonstrating how multi-omics integration could uncover complex pathway networking alterations following environmental stressors.

Plant Specialized Metabolism

Multi-omics integration has proven particularly valuable for elucidating plant specialized metabolic pathways, which are often difficult to characterize using traditional methods. In a study on the medicinal plant Bidens alba, integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics revealed organ-specific biosynthesis of flavonoids and terpenoids [14]. Researchers identified 774 flavonoids and 311 terpenoids across different tissues, with flavonoids enriched in aerial tissues while certain sesquiterpenes and triterpenes accumulated in roots [14].

Transcriptome profiling revealed tissue-specific expression of key biosynthetic genes—including CHS, F3H, FLS for flavonoids and HMGR, FPPS, GGPPS for terpenoids—that directly correlated with metabolite accumulation patterns [14]. Several transcription factors, including BpMYB1, BpMYB2, and BpbHLH1, were identified as candidate regulators of flavonoid biosynthesis, with BpMYB2 and BpbHLH1 showing contrasting expression between flowers and leaves [14]. For terpenoid biosynthesis, BpTPS1, BpTPS2, and BpTPS3 were identified as putative regulators. This systematic approach demonstrates how multi-omics integration can decode the complex regulatory networks underlying tissue-specific secondary metabolism in medicinal plants.

Multi-omics integration represents a paradigm shift in biosynthetic pathway elucidation, moving beyond single-layer analyses to provide comprehensive views of complex biological systems. The methodologies and case studies presented demonstrate how combining genomics, transcriptomics, and metabolomics enables researchers to connect genetic potential with metabolic outcomes, uncovering regulatory networks and pathway functionalities that remain invisible in isolated analyses. As the field advances, key considerations include the strategic selection of omics combinations rather than comprehensive inclusion of all available data types, implementation of robust reference materials like the Quartet standards for quality control, and adoption of ratio-based profiling approaches to enhance reproducibility across platforms and laboratories [10] [13].

Future developments will likely focus on improving computational methods for handling the complexity and volume of multi-omics data, particularly through artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches that can identify subtle patterns across omics layers [9] [11]. Additionally, the integration of temporal data through time-series experiments will provide dynamic views of pathway regulation and metabolic flux. As these technologies become more accessible and standardized, multi-omics integration will continue to transform our understanding of complex biological systems, accelerating the discovery of novel metabolic pathways and enabling more precise manipulation of biosynthetic processes for therapeutic and biotechnological applications.

Biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) are genomic regions containing collaboratively functioning genes that encode the biosynthetic machinery for producing secondary metabolites [16]. These metabolites, which include non-ribosomal peptides (NRPs), polyketides (PKs), ribosomally synthesized and post-translationally modified peptides (RiPPs), terpenoids, and siderophores, play crucial roles in microbial defense, communication, and environmental adaptation [17] [18] [16]. Beyond their biological functions, these compounds have significant pharmaceutical and biotechnological applications, serving as antibiotics, anticancer agents, immunosuppressants, and agrochemicals [18]. The identification and characterization of BGCs across biological kingdoms—from bacteria and archaea to plants—have been revolutionized by next-generation sequencing technologies and sophisticated bioinformatics tools [17] [16]. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of contemporary BGC discovery platforms, experimental validation methodologies, and research reagents, framed within the broader context of validating biosynthetic pathway functionality for drug development and natural product discovery.

Computational Tools for BGC Identification: A Performance Comparison

The initial identification of BGCs in genomic or metagenomic sequences relies predominantly on computational tools that employ either rule-based or machine learning approaches [16]. Rule-based methods like antiSMASH (antibiotics and Secondary Metabolite Analysis SHell) utilize known biosynthetic patterns and conserved domain databases to identify BGCs, while machine learning approaches leverage trained models to detect novel BGC classes beyond predefined categories [16]. More recently, deep learning models employing transformer architectures have demonstrated superior capability in capturing location-dependent relationships between biosynthetic genes, enabling more accurate prediction of both known and novel BGCs [16].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Major BGC Prediction Tools

| Tool | Approach | Strengths | Limitations | Reported AUROC | Speed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| antiSMASH | Rule-based | Excellent for known BGC categories; comprehensive annotation [18] | Limited novel BGC detection; scalability issues [16] | N/A (benchmark standard) | Moderate [16] |

| BGC-Prophet | Transformer-based deep learning | High accuracy; ultrahigh-throughput; novel BGC detection [16] | >90% [16] | Several orders faster than DeepBGC [16] | |

| DeepBGC | BiLSTM deep learning | Improved novel BGC detection over rule-based [16] | Loses long-range dependencies; computationally intensive [16] | Comparative benchmark | Slow [16] |

| ClusterFinder | Machine learning | Identifies putative BGCs [16] | Higher false positive rate [16] |

Table 2: BGC Type Distribution Across Phylogenetic Lineages

| BGC Type | Most Enriched Phyla/Environments | Potential Products | Detection Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Non-Ribosomal Peptide Synthetases (NRPS) | Actinomycetota, Marine bacteria [17] [18] | Antibiotics, siderophores [17] | Well-detected by both rule-based and ML tools [16] |

| Polyketide Synthases (PKS) | Actinomycetota, Marine γ-proteobacteria [18] [16] | Antimicrobials, anticancer agents [17] | Type I, II, III PKS require different detection rules [19] |

| Ribosomally Synthesized and Post-translationally Modified Peptides (RiPPs) | Widespread across lineages [16] | Antimicrobial peptides, toxic compounds [18] | Challenging due to precursor gene diversity; specialized tools needed (NeuRiPP, DeepRiPP) [16] |

| NI-siderophores | Marine Vibrio, Photobacterium [18] | Vibrioferrin, amphibactins [18] | Structural variability in accessory genes affects detection [18] |

| Terpenoids | Plants, some bacteria [19] [20] | Therapeutic compounds, pigments [20] | Plant BGCs less compact; require integrated omics [19] |

Experimental Protocols for BGC Characterization and Validation

Genome Sequencing, Assembly, and BGC Identification

Protocol Objective: Obtain high-quality genome sequences and identify putative BGCs.

Methodology:

- DNA Extraction: Use commercial kits (e.g., DNeasy UltraClean Microbial Kit) with quality control via agarose gel electrophoresis and quantification using fluorescent assays (Qubit dsDNA HS Assay Kit) [17].

- Sequencing: Employ both short-read (Illumina NovaSeq, 2×150 bp) and long-read (Oxford Nanopore Technologies MinION) platforms for hybrid assembly [17].

- Genome Assembly and Polishing: Perform hybrid assembly using Unicycler v0.4.8, followed by sequential polishing with Medaka v1.2.3 (ONT reads) and Polypolish v0.5.0/polCA v4.0.5 (Illumina reads) [17].

- Quality Assessment: Evaluate assembly quality using Quast v5.0.2 and CheckM v1.1.3 [17].

- BGC Prediction: Screen assembled genomes using antiSMASH 7.0 with default settings, enabling KnownClusterBlast, ClusterBlast, SubClusterBlast, and Pfam domain annotation [18].

Technical Notes: Hybrid assembly produces more complete genomes, essential for identifying intact BGCs. antiSMASH parameters should be adjusted based on kingdom-specific considerations—bacterial BGCs are typically more compact and easier to delineate than plant BGCs, which may require additional co-expression evidence [19] [18].

Phylogenetic and Comparative Genomic Analysis of BGCs

Protocol Objective: Contextualize identified BGCs within evolutionary frameworks and assess their diversity.

Methodology:

- Gene Cluster Family (GCF) Analysis: Process antiSMASH results with BiG-SCAPE (Biosynthetic Gene Similarity Clustering and Prospecting Engine) v2.0 to group BGCs into families based on domain sequence similarity [18].

- Network Visualization: Import BiG-SCAPE output networks into Cytoscape v3.10.3 for visualization and exploration [18].

- Phylogenetic Analysis: For specific BGC families (e.g., NI-siderophores), extract core biosynthetic genes, perform multiple sequence alignment using Clustal Omega, and construct maximum likelihood phylogenies with MEGA11 (1000 bootstrap replicates) [18].

- Genetic Variability Assessment: Annotate alignments in Geneious Prime to identify conserved core biosynthetic genes and variable accessory regions [18].

Technical Notes: BiG-SCAPE similarity cutoffs of 30% define broad gene cluster families, while 10% resolves fine-scale diversity [18]. For vibrioferrin BGCs, this approach revealed 12 families at 10% similarity that merged into one GCF at 30% similarity [18].

Functional Validation of BGC Pathway

Protocol Objective: Confirm the biosynthetic capability of predicted BGCs and elucidate pathway steps.

Methodology:

- Heterologous Expression: Clone candidate genes into appropriate expression vectors (e.g., pET series for E. coli, yeast integration vectors for S. cerevisiae) [21].

- Enzyme Assays: Purify recombinant enzymes (e.g., via Ni-affinity chromatography) and perform in vitro activity assays with proposed substrates and cofactors [21].

- Pathway Reconstitution: Use transient expression systems (e.g., Agrobacterium-mediated infiltration in Nicotiana benthamiana) to co-express multiple pathway genes [21] [20].

- Gene Silencing: Implement virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) in native hosts to disrupt candidate genes and observe metabolic consequences [21].

- Metabolite Analysis: Employ liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (LC-MS) to identify and quantify pathway intermediates and final products [21].

Technical Notes: For plant BGCs with non-compact architecture, co-expression analysis of transcriptomic and metabolomic data across tissues helps establish gene-to-metabolite relationships before functional validation [19] [21]. In the elucidation of the hydroxysafflor yellow A pathway, this integrated approach identified CtCGT, CtF6H, Ct2OGD1, and CtCHI1 as key enzymes, which were subsequently validated through VIGS, heterologous expression in N. benthamiana, and in vitro assays [21].

BGC Characterization Workflow

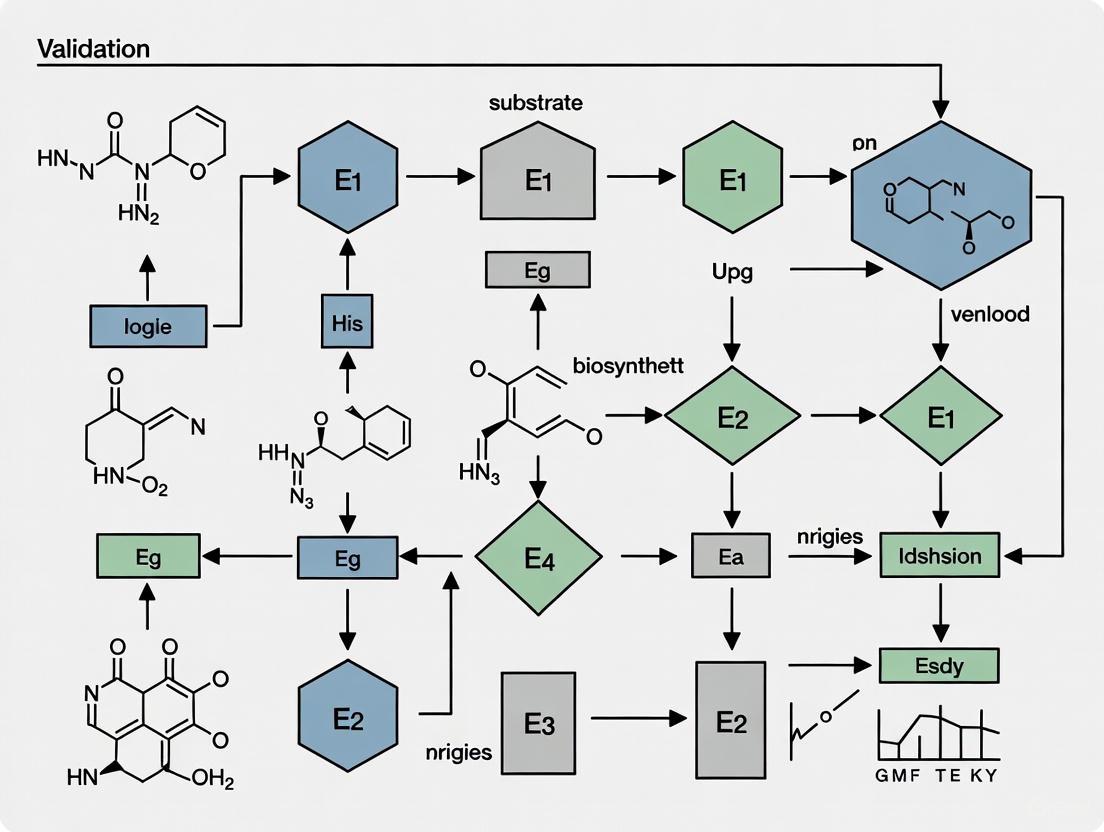

The following diagram illustrates the integrated computational and experimental workflow for BGC identification and characterization:

BGC Identification and Characterization Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions for BGC Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for BGC Identification and Characterization

| Category | Specific Reagents/Tools | Function/Application | Examples from Literature |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Sequencing Kits | Illumina NovaSeq, Oxford Nanopore Rapid Sequencing Kit (SQK-RBK004) [17] | Whole genome sequencing for BGC discovery | Antarctic Actinomycetota strain analysis [17] |

| DNA Extraction Kits | DNeasy UltraClean Microbial Kit [17] | High-quality DNA extraction from microbial cultures | Antarctic strain genome sequencing [17] |

| BGC Prediction Software | antiSMASH 7.0 [18], BGC-Prophet [16], BiG-SCAPE [18] | BGC identification, classification, and comparative analysis | Marine bacteria BGC diversity studies [18] |

| Pathway Databases | MIBiG [16], KEGG [22], MetaCyc [22] | Reference data for known BGCs and pathways | Vibrioferrin BGC annotation [18] |

| Compound Databases | PubChem [22], NPAtlas [22], LOTUS [22] | Metabolite structure and bioactivity information | Natural product identification [22] |

| Enzyme Databases | BRENDA [22], UniProt [22], PDB [22] | Enzyme functional and structural information | Candidate enzyme characterization [21] |

| Cloning & Expression Systems | pET vectors (E. coli), WAT11 yeast [21], Agrobacterium (N. benthamiana) [21] [20] | Heterologous expression of BGC genes | HSYA pathway elucidation [21] |

| Chromatography & MS | LC-MS systems [21] | Metabolite separation and identification | HSYA quantification in safflower [21] |

The integration of computational prediction tools with experimental validation frameworks has dramatically accelerated the pace of BGC discovery and characterization across biological kingdoms. While rule-based methods like antiSMASH remain robust for identifying known BGC classes, emerging deep learning approaches such as BGC-Prophet offer unprecedented scalability and sensitivity for novel BGC detection [16]. However, computational prediction represents only the initial phase—comprehensive functional validation requires sophisticated experimental workflows including heterologous expression, enzyme assays, and metabolic profiling [21]. The continuing evolution of BGC research methodologies, particularly the integration of multi-omics data and the development of kingdom-specific approaches, promises to unlock the vast potential of biosynthetic gene clusters for drug discovery and biotechnology applications. As these tools become more accessible and refined, researchers will be better equipped to navigate the complex landscape of biosynthetic pathway functionality, ultimately enabling the sustainable production of valuable natural products through synthetic biology approaches [19] [20].

This guide provides an objective comparison of four key bioinformatics resources—LOTUS, KEGG, MetaCyc, and MIBiG—for researchers validating biosynthetic pathway functionality. The evaluation focuses on data content, curation quality, and applicability in drug discovery and metabolic engineering.

LOTUS (The Natural Products Online Database) is an open, curated resource integrating chemical, taxonomic, and spectral data of natural products to accelerate research in metabolomics and natural product discovery [22]. It serves as a key resource for identifying novel bioactive compounds.

KEGG (Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes) is a comprehensive database that integrates genomic, chemical, and systemic functional information [22]. It provides valuable data on pathways, diseases, drugs, and organisms, making it a cornerstone for bioinformatics and systems biology studies [22]. KEGG pathways often represent consolidated mosaics of related metabolic functions from multiple species rather than organism-specific pathways [23] [24].

MetaCyc is a curated database of experimentally elucidated metabolic pathways and enzymes, providing detailed information on biochemical reactions across diverse organisms [22]. It collects pathways with experimentally demonstrated functionality, emphasizing a higher degree of manual curation and organism-specific pathway definitions compared to KEGG [23] [24]. It also includes attributes like taxonomic range and enzyme regulators that enhance pathway prediction accuracy [23] [25].

MIBiG (Minimum Information about a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster) is a standardized framework for annotating and reporting biosynthetic gene clusters for natural products, enabling systematic data sharing and comparative analysis [22]. While not a database per se, it provides critical community standards for biosynthetic pathway data.

Quantitative Comparison of Database Content

Table 1: Comparative quantitative analysis of database content and coverage

| Resource | Primary Content Type | Pathway Count | Reaction Count | Compound Count | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LOTUS | Natural product compounds & occurrences | N/A | N/A | 130,000+ natural products (as of 2025) [22] | Focus on natural products with taxonomic origins |

| KEGG | Integrated pathways & networks | 179 modules, 237 maps [23] | 8,692 total (6,174 in pathways) [23] | 16,586 total (6,912 as substrates) [23] | Broad coverage of metabolic & non-metabolic pathways |

| MetaCyc | Curated metabolic pathways | 1,846 base pathways, 296 super pathways [23] | 10,262 total (6,348 in pathways) [23] | 11,991 total (8,891 as substrates) [23] | Higher curation depth, organism-specific pathways |

| MIBiG | Biosynthetic gene cluster standards | N/A | N/A | N/A | Standardized annotation for natural product biosynthesis |

Table 2: Qualitative comparison of database attributes and applications

| Attribute | KEGG | MetaCyc | LOTUS | MIBiG |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Curation Level | Moderate (reference pathways only) [24] | High (extensive manual curation) [24] | Curated natural products [22] | Community standard |

| Taxonomic Range | Broad, multi-species | Specific, organism-focused | Natural product-producing organisms | Microbial biosynthetic clusters |

| Pathway Conceptualization | Consolidated metabolic maps [24] | Individual biological pathways [24] | Natural product occurrences | Biosynthetic gene clusters |

| Experimental Data | Limited experimental metadata | Extensive (kinetics, regulation, citations) [24] | Chemical structures & spectral data | Gene cluster annotations |

| Drug Discovery Utility | Pathway context for drug targets | Metabolic pathway engineering | Natural product identification | Natural product biosynthesis |

Experimental Validation Protocols

Protocol for Cross-Database Pathway Validation

Objective: To experimentally validate the functional presence of a predicted biosynthetic pathway using multi-database evidence.

Materials:

- Target organism genomic DNA

- HPLC-MS system for metabolite profiling

- cDNA synthesis kit for transcript analysis

- PCR reagents and primers

- Relevant chemical standards

Methodology:

In Silico Prediction Phase

- Query target compound in LOTUS to identify known producers and structural analogs [22]

- Search KEGG for conserved pathway modules associated with target compound class [24]

- Consult MetaCyc for experimentally validated pathway variants and enzyme mechanisms [23]

- Check MIBiG for characterized biosynthetic gene clusters producing similar compounds [22]

Genomic Validation

- Design PCR primers based on conserved enzyme domains identified across databases

- Amplify candidate genes from target organism genomic DNA

- Sequence and confirm homology to known biosynthetic genes

Functional Validation

- Measure transcript levels of candidate genes under inducing conditions

- Profile metabolite production using HPLC-MS

- Correlate gene expression with metabolite accumulation

- Heterologously express candidate genes in model host for functional confirmation

Validation Metrics: Pathway confirmation requires (1) genomic presence of all essential enzymes, (2) correlation between gene expression and product accumulation, and (3) enzymatic activity demonstration in vitro.

Protocol for Database Accuracy Assessment

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate the accuracy and completeness of pathway predictions from different databases.

Experimental Design:

- Select a benchmark set of 10-20 well-characterized biosynthetic pathways

- Extract pathway predictions from each database for identical starting compounds

- Compare predictions against experimentally validated pathways from literature

- Evaluate using precision, recall, and F1-score metrics

Analysis Workflow:

Experimental Workflow for Pathway Validation

The following diagram illustrates the integrated experimental workflow for validating biosynthetic pathways using multiple database resources:

Table 3: Key research reagent solutions for biosynthetic pathway validation

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Pathway Validation | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| KEGG MODULE | Identifies conserved functional units in metabolism | Rapid assessment of pathway completeness in new genomes [23] |

| MetaCyc Enzyme Profiles | Provides detailed enzyme kinetic data and regulatory information | Predicting rate-limiting steps in heterologous expression [24] |

| LOTUS Natural Product Records | Links compounds to producing organisms and chemical structures | Identifying candidate organisms for pathway discovery [22] |

| MIBiG Annotation Standards | Ensures consistent reporting of biosynthetic gene clusters | Comparative analysis of natural product biosynthesis across species [22] |

| Pathway Tools Software | Enables visualization and analysis of metabolic networks | Creating organism-specific metabolic models from MetaCyc data [24] |

This comparison demonstrates that LOTUS, KEGG, MetaCyc, and MIBiG offer complementary strengths for biosynthetic pathway validation. KEGG provides the most extensive compound coverage and broad metabolic maps, while MetaCyc offers superior curation depth and organism-specific pathway definitions. LOTUS delivers unique value for natural product discovery, and MIBiG provides essential standardization for biosynthetic gene cluster characterization. Researchers validating pathway functionality should employ an integrated approach, leveraging the distinct advantages of each resource while acknowledging their specific limitations in coverage, curation, and pathway conceptualization.

The field of biosynthetic pathway discovery is undergoing a fundamental transformation, moving from traditional, hypothesis-driven targeted methods to comprehensive, data-rich untargeted approaches. This paradigm shift is redefining how researchers validate pathway functionality, leveraging advanced analytical technologies and computational tools to uncover complex metabolic networks without prior assumptions. This guide objectively compares the performance of these methodologies within the broader context of validating biosynthetic pathway functionality.

The choice between targeted and untargeted metabolomics represents a fundamental decision in experimental design, with each approach offering distinct advantages and limitations for pathway discovery [26].

Targeted metabolomics is a hypothesis-driven approach that requires a previously characterized set of metabolites for analysis. It applies absolute quantification using isotopically labeled standards to measure approximately 20 predefined metabolites with high precision, reducing false positives and analytical artifacts. This method is ideal for validating previously identified processes and establishing baseline measurements in healthy versus impaired comparisons [26].

Untargeted metabolomics establishes foundations for discovery and hypothesis generation. This global approach involves qualitative identification and relative quantification of thousands of endogenous metabolites in biological samples, both known and unknown. It enables an unbiased systematic measurement of a large number of metabolites, leading to the discovery of previously unidentified or unexpected changes relevant to pathway elucidation [26].

The evolution from targeted to untargeted strategies reflects the growing emphasis on comprehensive system-level understanding in biosynthetic research, particularly valuable for de novo pathway discovery where the full metabolic landscape is uncharted [27].

Performance Comparison: Experimental Data and Metrics

A 2025 comparative study evaluating enrichment methods for untargeted metabolomics provides critical performance data that highlights the practical implications of this paradigm shift [28]. The research compared three popular enrichment analysis approaches—Metabolite Set Enrichment Analysis (MSEA), Mummichog, and Over Representation Analysis (ORA)—using data from Hep-G2 cells treated with 11 compounds with five different mechanisms of action.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Enrichment Analysis Methods for Untargeted Metabolomics

| Method | Similarity to Other Methods | Consistency | Correctness | Overall Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mummichog | Moderate similarity with MSEA | Highest | Highest | Best performance for in vitro data |

| MSEA | Highest similarity with Mummichog | Moderate | Moderate | Outperformed by Mummichog |

| ORA | Low similarity with other methods | Lowest | Lowest | Poorest performance |

The study concluded that Mummichog showed the best performance for in vitro untargeted metabolomics data in terms of consistency and correctness, highlighting the importance of selecting appropriate computational tools to maximize the value of untargeted approaches [28].

Table 2: Characteristics of Targeted vs. Untargeted Metabolomics

| Characteristic | Targeted Metabolomics | Untargeted Metabolomics |

|---|---|---|

| Scope | ~20 predefined, known metabolites | Thousands of metabolites, known and unknown |

| Quantification | Absolute using isotopic standards | Relative quantification |

| Precision | High | Decreased due to relative quantification |

| Bias | Reduced dominance of high-abundance molecules | Bias toward higher abundance metabolites |

| Primary Application | Hypothesis testing and validation | Discovery and hypothesis generation |

| Data Complexity | Lower, more manageable | High, requires extensive processing |

| Identification Challenge | Minimal (pre-characterized metabolites) | High for unknown metabolites |

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Pathway Validation

The validation of biosynthetic pathway functionality employs distinct experimental workflows depending on the approach taken. Below are the detailed methodologies for implementing these paradigms in research settings.

Targeted Pathway Validation Protocol

Targeted approaches follow a focused, sequential workflow for hypothesis-driven validation [26]:

Sample Preparation:

- Apply extraction procedures optimized for specific metabolites

- Incorporate relevant internal standards for quantification

- Use purification techniques to reduce matrix effects

Data Acquisition:

- Utilize LC-MS, GC-MS, or NMR platforms with method parameters optimized for target analytes

- Employ multiple reaction monitoring (MRM) on mass spectrometers for enhanced sensitivity

- Implement calibration curves with isotopically labeled standards

Data Analysis:

- Apply absolute quantification against standard curves

- Perform statistical analysis (e.g., t-tests, ANOVA) on predefined metabolite sets

- Conduct pathway mapping using established databases (KEGG, MetaCyc)

Untargeted Pathway Discovery Protocol

A 2025 study on oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neurotoxicity exemplifies a modern untargeted workflow [29]:

Sample Preparation:

- Collect biological samples (e.g., 84 serum samples from gastric cancer patients)

- Apply global metabolite extraction procedures (no specific internal standards required)

- Use protein precipitation and sample dilution as needed

Data Acquisition:

- Employ ultra-high-performance liquid chromatography-Q-Exactive Orbitrap tandem mass spectrometry (UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap-MS/MS)

- Implement full-scan mode to capture all detectable ions

- Include quality control samples (pooled quality controls) throughout the run

Data Processing:

- Perform peak picking, alignment, and normalization using platforms like MetaboScape

- Conduct multivariate statistical analysis (PCA, PLS-DA) to identify differentially expressed metabolites

- Apply false discovery rate (FDR) correction for multiple comparisons

Pathway Analysis:

- Utilize enrichment analysis methods (Mummichog, MSEA, ORA)

- Integrate SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) analysis to identify key biomarkers

- Perform pathway enrichment analysis to identify affected metabolic pathways

Integrated Approaches: Bridging Discovery and Validation

Contemporary research increasingly demonstrates that the most effective strategy for pathway validation involves integrating both targeted and untargeted approaches [26]. This hybrid methodology leverages the strengths of both paradigms while mitigating their respective limitations.

One effective integrated workflow involves:

- Discovery Phase: Using untargeted metabolomics to screen novel candidate biomarkers and identify potential pathway alterations [29]

- Validation Phase: Applying targeted metabolomics with absolute quantification to verify the identified biomarkers and precisely measure their changes [26]

- Functional Validation: Implementing heterologous expression systems (e.g., Nicotiana benthamiana) to experimentally confirm pathway functionality [20]

This integrated approach has delivered valuable insights across multiple domains. In plant natural products research, combining multi-omics data with functional validation has accelerated the elucidation of complex biosynthetic pathways for compounds like strychnine, vinblastine, and colchicine [27]. Similarly, in clinical research, this strategy has identified novel biomarkers for oxaliplatin-induced peripheral neuropathy, revealing alterations in amino acid metabolism, lipid metabolism, and nervous system metabolism [29].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Successful implementation of pathway discovery and validation workflows requires specific research reagents and analytical solutions.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Solutions for Pathway Validation

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| UHPLC-Q-Exactive Orbitrap-MS/MS | High-resolution separation and detection of metabolites | Untargeted metabolomics for comprehensive metabolite profiling [29] |

| Isotopically Labeled Standards | Enable absolute quantification of specific metabolites | Targeted metabolomics for precise measurement of known compounds [26] |

| MetaboAnalyst Software | Web-based platform for enrichment analysis | Statistical and bioinformatic interpretation of untargeted data [28] |

| Nicotiana benthamiana | Plant-based heterologous expression system | Functional validation of putative biosynthetic pathways [20] |

| Agrobacterium tumefaciens | Vector for transient gene expression in plants | Delivery of candidate genes for functional characterization [27] |

| CRISPR/Cas9 Systems | Precise genome editing tool | Functional validation of candidate genes in native hosts [20] |

| Solvent Extraction Mixtures | Global metabolite extraction from biological samples | Sample preparation for untargeted metabolomics [26] |

The evolution from targeted to untargeted approaches represents not a replacement but an expansion of the methodological toolkit for validating biosynthetic pathway functionality. While untargeted methods excel at novel pathway discovery and hypothesis generation, targeted approaches remain indispensable for precise validation and quantification. The emerging paradigm emphasizes integrative strategies that leverage the comprehensive scope of untargeted methods with the precision of targeted approaches, accelerated by advanced computational tools like Mummichog for enrichment analysis and heterologous expression systems for functional validation. This synergistic framework enables researchers to more efficiently bridge the gap between pathway discovery and functional validation, ultimately accelerating the development of biologically significant findings into therapeutic applications.

Advanced Tools and Techniques for Pathway Prediction and Assembly

Elucidating the biosynthetic pathways of specialized metabolites is a fundamental challenge in plant biology and drug development. For decades, discovery approaches have primarily been target-based, relying heavily on prior knowledge of a specific compound or enzyme to serve as 'bait' for identifying other pathway components [8] [30]. This requirement presents a significant bottleneck, leaving the vast landscape of plant 'dark matter'—metabolites with unknown structures and functions—largely unexplored [8]. While single-omics technologies (genomics, transcriptomics, or metabolomics) have successfully characterized selected pathways, they often fail to provide a systematic view of the entire biosynthetic process [31]. Integrative multi-omics strategies offer a promising solution by providing a comprehensive perspective on the cooperative interplay of genes and metabolites. In this context, MEANtools emerges as a systematic and unsupervised computational workflow designed to predict candidate metabolic pathways de novo by leveraging paired transcriptomic and metabolomic data, without the need for prior knowledge [8] [30] [32].

MEANtools: Workflow and Core Computational Methodology

MEANtools (Multi-omics Integration for Metabolic Pathway Prediction) integrates mass features from metabolomics data and transcripts from transcriptomics data to predict plausible metabolic reactions, generating testable hypotheses for experimental validation [30]. Its analytical power stems from a structured workflow that combines statistical integration with biochemical reaction rules.

The MEANtools Analytical Pipeline

The MEANtools workflow can be dissected into several core stages, as visualized below.

Data Integration and Correlation Analysis: The process begins with formatting and annotating input transcriptomic and metabolomic data, ideally from experiments spanning various conditions, tissues, and time points [8]. MEANtools then employs a mutual rank (MR)-based correlation method to identify mass features (putative metabolites) and transcripts that show highly correlated abundance patterns across samples [8] [30]. This step is crucial for reducing false positives that commonly occur when correlation is used in isolation [8].

Database-Driven Annotation and Prediction: In parallel, the pipeline annotates mass features by matching their masses to known metabolite structures in the LOTUS database, a comprehensive resource of natural products [8] [30]. Concurrently, it leverages the RetroRules database, which contains general enzymatic reaction rules annotated with associated protein domains and enzyme families [8]. MEANtools cross-references these reaction rules with the correlated transcripts, assessing whether the enzymatic reactions they represent can logically connect the correlated mass features based on mass shifts and structural compatibility [8] [30]. This integration allows MEANtools to construct a directed reaction network where nodes are mass features and edges are enzymatic reactions, enabling the de novo prediction of candidate metabolic pathways [30].

Performance Comparison: MEANtools vs. Alternative Approaches

The performance of MEANtools can be objectively evaluated by comparing its methodology and validation outcomes with those of other prevalent computational strategies in plant biosynthetic pathway discovery.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Computational Approaches for Pathway Discovery

| Feature / Tool | MEANtools | Genomics/plantiSMASH | Transcriptomic Co-expression | Metabolomic Mass Shift Networks |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Omics Data | Transcriptomics, Metabolomics | Genomics | Transcriptomics | Metabolomics |

| Core Methodology | Mutual-rank correlation + Reaction rule integration | Identification of genomic co-localization (BGCs) | Gene expression pattern correlation | Analysis of mass differences between features |

| Prior Knowledge Dependency | Unsupervised (Low) [8] | Low (for BGC prediction) | High (often requires bait gene) [8] [31] | Medium (requires predefined transformations) |

| Key Strength | Untargeted, systematic hypothesis generation; Integrates biological activity (correlation) with biochemical logic [30] | Effective for clustered pathways; identifies physical gene linkages [31] | Powerful for co-regulated, non-clustered genes [31] | Excellent for proposing structural relationships between metabolites |

| Key Limitation | Reliability depends on database coverage (e.g., RetroRules, LOTUS) [30] | Many plant pathways are not clustered [31] | High rate of false positives without additional filtering [8] | Cannot directly link metabolites to genes/enzymes |

| Experimental Validation (Case Study) | 5/7 steps correctly predicted in tomato falcarindiol pathway [8] [32] | Has characterized ~30-40 BGCs in plants [31] | Successfully used in noscapine and podophyllotoxin pathways [31] | Used in tools like MetaNetter; validation is metabolite-focused [8] |

This comparison highlights MEANtools' distinctive position as an integrator. While genomics-based tools like plantiSMASH are powerful for finding biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), a significant portion of plant metabolic pathways are not genetically co-localized [31]. Conversely, transcriptomic co-expression analyses can find related genes but often produce false positives and require a starting point [8]. MEANtools addresses these gaps by combining the strengths of these methods, using correlation to find associations and biochemical rules to validate their plausibility, all within an unsupervised framework.

Experimental Validation and Application

The true value of a computational tool lies in its performance against experimentally characterized pathways. MEANtools has been rigorously validated using a real-world case study.

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Falcarindiol Pathway Validation

The validation methodology for MEANtools serves as a template for testing its predictive power [8] [30]:

- Dataset Curation: A paired transcriptomic and metabolomic dataset previously generated to reconstruct the falcarindiol biosynthetic pathway in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) was used. The data was sourced from public repositories (NCBI BioProject: PRJNA509154 and EBI's MetaboLights: MTBLS1039) [8].

- Data Pre-processing: The raw omics data underwent pre-processing. This included generating an expression matrix from the RNA-seq data and a feature table with m/z values and retention times from the metabolomic data [8].

- MEANtools Execution: The pre-processed data were input into the MEANtools pipeline. The tool computed mutual-rank correlations between all transcripts and mass features.

- Pathway Prediction: Using the correlated pairs and the integrated RetroRules and LOTUS databases, MEANtools generated a network of putative reactions and pathways.

- Result Comparison: The computationally predicted pathway steps were directly compared to the seven enzymatically characterized steps of the falcarindiol biosynthetic pathway.

Key Experimental Findings and Performance

In this validation experiment, MEANtools correctly anticipated five out of the seven characterized steps in the falcarindiol pathway [8] [32]. This high rate of success demonstrates the tool's potential for accurate, untargeted hypothesis generation. Furthermore, the analysis identified other candidate pathways involved in specialized metabolism, showcasing its ability to uncover novel biological insights beyond the specific pathway used for validation [8].

The following diagram illustrates the logical process of this validation experiment, from data input to the final comparative analysis.

The application of MEANtools and similar integrative workflows relies on a foundation of specific computational and data resources. The table below details key components of this research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Resources for Multi-omics Pathway Discovery

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Workflow |

|---|---|---|

| RetroRules Database [8] [30] | Biochemical Database | Provides a comprehensive set of enzymatic reaction rules, annotated with enzyme families (e.g., PFAM), used to link correlated transcripts to plausible biochemical transformations. |

| LOTUS Database [8] [30] | Natural Product Database | A curated resource of known natural product structures used to annotate mass features from metabolomics data by molecular weight matching. |

| MetaNetX [30] | Metabolic Network Repository | Used to identify mass shifts between substrates and products of enzymatic reactions, facilitating the matching of mass differences in the data to known biochemical reactions. |

| Paired Omics Datasets | Data | Simultaneously generated transcriptomic and metabolomic data from the same samples under varying conditions; the fundamental input for correlation analysis. |

| MEANtools Software [8] | Computational Workflow | The core integrative platform that executes the correlation, database query, and network prediction steps. It is open-source and freely available on GitHub. |

MEANtools represents a significant paradigm shift in computational biosynthetic pathway discovery. By moving from a targeted, knowledge-dependent approach to a systematic, unsupervised integration of multi-omics data, it directly addresses the challenge of plant metabolic "dark matter." Its validated performance in predicting over 70% of a known pathway, combined with its ability to generate novel, testable hypotheses, makes it a powerful addition to the toolkit of researchers and drug development professionals. As public omics datasets continue to expand, tools like MEANtools will become increasingly critical for unlocking the full potential of plant specialized metabolism for applications in medicine and biotechnology.

The design of efficient biosynthetic pathways is a cornerstone of synthetic biology, enabling the production of high-value compounds, from renewable biofuels to anticancer drugs [22]. However, this process is notoriously challenging and time-consuming, often requiring massive investment of human effort to navigate the vast chemical and enzymatic search space [22]. Traditional rule-based computational methods, which rely on manually encoded chemical knowledge, have been limited in their scalability and ability to generalize to novel compounds [33].

The advent of artificial intelligence (AI) has ushered in a new paradigm. Template-free, deep learning models, particularly those leveraging the Transformer architecture, are now capable of learning the complex patterns of organic and biochemical reactions directly from data, mimicking human chemical intuition [33] [34]. These models have dramatically advanced the field of retrosynthesis prediction, a crucial task where the goal is to identify precursor molecules for a given target compound. Among these new approaches, the Graph-Sequence Enhanced Transformer (GSETransformer) has emerged as a powerful tool specifically touted for its performance on the complex structures of natural products [35].

This guide provides an objective comparison of GSETransformer against other leading AI-driven retrosynthesis models. By synthesizing current research, presenting quantitative performance data, and detailing experimental methodologies, we aim to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the information needed to select and validate appropriate computational tools for their work in biosynthetic pathway design.

Comparative Analysis of Retrosynthesis Models

The landscape of AI models for retrosynthesis can be broadly categorized into template-based, semi-template-based, and template-free approaches [34]. More recently, the differentiation has also centered on the underlying architecture, with Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), Transformers, and hybrid models representing the state of the art. The following table summarizes the key characteristics and reported performance of several prominent models.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of AI-Driven Retrosynthesis Models

| Model Name | Model Type | Architecture | Key Innovation | Reported Top-1 Accuracy (USPTO-50k) | Strengths / Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GSETransformer [35] | Template-Free | Graph-Sequence Transformer | Integrates graph structural information with sequential dependencies. | State-of-the-art (Specific value not provided in search results) | Natural Product biosynthesis; single- & multi-step tasks. |

| RSGPT [34] | Template-Free | Generative Pretrained Transformer | Pre-trained on 10 billion synthetic data points; uses RLAIF. | 63.4% | Massive-scale pre-training; high accuracy on benchmark datasets. |

| Molecular Transformer [33] | Template-Free | Sequence-to-Sequence Transformer | Treats retrosynthesis as a machine translation task using SMILES. | ~54.1% (with extended training) [33] | Pioneering model; predicts reactants, reagents, and solvents. |

| Graph2Edits [34] | Semi-Template-Based | Graph Neural Network | End-to-end model predicting a sequence of graph edits. | N/A | Improved interpretability and handling of complex reactions. |

| GNN Baselines (e.g., ChemProp) [36] | Varies | Graph Neural Network | Message-passing neural networks on molecular graphs. | Varies (Used as baseline in studies) | Strong performance on many molecular property tasks. |

The search results highlight RSGPT as the current benchmark for raw prediction accuracy on standard datasets, achieving a remarkable 63.4% Top-1 accuracy on the USPTO-50k dataset [34]. This performance is attributed to its unprecedented scale of pre-training on 10 billion synthetically generated reaction datapoints, followed by reinforcement learning from AI feedback (RLAIF) [34].

In contrast, while specific accuracy scores for GSETransformer are not provided in the searched literature, it is explicitly noted for achieving state-of-the-art performance in the specific domain of natural product (NP) biosynthesis [35]. Its key innovation lies in its hybrid graph-sequence architecture, which allows it to leverage both the spatial-structural information from molecular graphs and the sequential patterns learned from SMILES strings. This is particularly valuable for NPs, which often possess complex, chiral, and highly functionalized structures that are poorly characterized by traditional methods [35].

Other models like the Molecular Transformer represent foundational work in treating chemistry as a language, while semi-template-based approaches like Graph2Edits offer a different balance between accuracy and interpretability [34] [33].

Experimental Protocols for Model Validation

To objectively compare these models and validate their predictions for biosynthetic pathway functionality, researchers rely on standardized benchmarks and rigorous evaluation metrics. Below is a detailed methodology for a typical validation experiment as described across multiple studies.

Dataset Preparation and Benchmarking

- Datasets: The most commonly used benchmark is the USPTO dataset, with USPTO-50k (containing 50,000 reactions) and USPTO-FULL (containing ~2 million reactions) being the standard for training and evaluation [34] [33]. For biosynthesis, specialized datasets containing enzymatic reactions are used.

- Data Splitting: Datasets are split into training, validation, and test sets, typically using a temporal or random split to ensure the model is evaluated on unseen data.

- Input Representation: Models are fed with the product molecule(s). For sequence-based models (e.g., RSGPT, Molecular Transformer), this is the SMILES string of the product [34] [33]. For graph-based models (e.g., GSETransformer, GNNs), the input is a molecular graph where nodes represent atoms and edges represent bonds [36] [35].

Model Training and Evaluation Metrics

- Training Protocol: Models are trained to predict the reactant(s) given the product. State-of-the-art models like RSGPT employ a multi-stage process: 1) Pre-training on a massive corpus of synthetic data, 2) Reinforcement Learning from AI Feedback (RLAIF), where the model's own predictions are validated by an algorithm (e.g., RDChiral) and rewarded for correctness, and 3) Fine-tuning on the target benchmark dataset [34].

- Key Metrics:

- Top-N Accuracy: The percentage of test reactions for which the correct set of reactants is found within the model's top N predictions. Top-1 accuracy is the most stringent metric [34] [33].

- Round-Trip Accuracy: A robust metric introduced to validate single-step predictions. It checks if the suggested precursors, when fed into a forward reaction prediction model, produce the original target product [33].

- Coverage and Diversity: Measure the model's ability to propose valid routes for a wide range of targets and suggest chemically diverse solutions [33].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Retrosynthesis

| Reagent / Resource | Type | Function in Research | Example / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| USPTO Dataset | Chemical Reaction Data | Provides standardized, annotated reaction data for training and benchmarking retrosynthesis AI models. | United States Patent and Trademark Office [34] [33] |

| RDChiral | Algorithm | A reverse synthesis template extraction algorithm used to generate synthetic reaction data and validate proposed reaction steps. | [34] |

| SMILES | Molecular Representation | A string-based notation for representing molecular structures; the "language" for sequence-based AI models. | [34] [33] |

| Molecular Graph | Molecular Representation | A graph-based representation where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges; the input for graph-based AI models. | [36] [35] |

| ECFP Fingerprints | Molecular Descriptor | A fixed-length vector representing molecular features; used as input for traditional machine learning baselines (e.g., XGBoost). | Extended Connectivity Fingerprints [36] |

| Reaction Classifier | Evaluation Model | A separate model that classifies the type of predicted reaction, used to assess the chemical plausibility of a proposed step. | [33] |

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow for the multi-stage training and validation process used by advanced models like RSGPT, integrating both synthetic data generation and RLAIF.

Architectural Insights: GSETransformer and Graph-Based Models

A key differentiator among modern retrosynthesis models is their underlying architecture and how they represent molecular information. The competition between Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Transformer-based models is particularly relevant.

GNNs, such as ChemProp and GIN-VN, operate on molecular graphs through a message-passing mechanism, where nodes (atoms) update their states by aggregating information from their neighbors (bonds) [36]. While highly effective for capturing local chemical environments, traditional GNNs can struggle with capturing long-range dependencies within a large molecular graph [37].

Pure Transformer models (e.g., Molecular Transformer) use self-attention mechanisms that allow every atom in a molecule (represented as a token in a SMILES string) to interact with every other atom, effectively modeling global relationships [33]. However, this comes at the cost of quadratic computational complexity, and the SMILES representation can sometimes lack explicit structural information [37] [36].

The GSETransformer represents a hybrid approach designed to get the best of both worlds. It is a graph-sequence model that enhances the transformer architecture by explicitly incorporating graph structural information [35]. This allows it to better handle the complex spatial and chiral arrangements prevalent in natural products, which are often lost in sequential SMILES representations.

Furthermore, research into Graph Transformers (GTs) like Graphormer shows that they can be competitive with or even surpass GNNs on various molecular property prediction tasks, especially when enriched with 3D structural context or trained with auxiliary tasks [36]. However, their computational cost remains a challenge. Innovations like the GECO layer have been proposed to replace the standard self-attention mechanism with a more scalable combination of local propagation and global convolutions, offering a quasilinear alternative for large-scale graph learning [37]. The following diagram illustrates the core architectural difference between a standard GNN and a Graph-Transformer hybrid, akin to the GSETransformer's design.

The field of AI-driven retrosynthesis is rapidly evolving, with different models excelling in different dimensions. For researchers whose primary goal is achieving the highest possible accuracy on standard organic chemistry benchmarks, models like RSGPT, trained on billions of data points, currently set the bar. However, for the critical task of biosynthetic pathway design, particularly for complex natural products, the GSETransformer presents a compelling, state-of-the-art alternative. Its hybrid graph-sequence architecture is specifically engineered to capture the intricate structural nuances of these molecules, an area where pure sequence-based models may falter.

Validation of these tools remains paramount. Integrating round-trip accuracy checks and pathway feasibility assessment within a broader Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle is essential for transitioning computational predictions into functional biosynthetic pathways in the lab. As these models continue to develop, the integration of ever-larger datasets, more sophisticated reinforcement learning strategies, and scalable architectures will further close the gap between computational prediction and empirical feasibility, solidifying AI's role as an indispensable partner in synthetic biology.

The design and optimization of biosynthetic pathways in living cells is a cornerstone of synthetic biology and metabolic engineering, with profound implications for sustainable manufacturing, therapeutic development, and basic research. However, a significant bottleneck has persisted: the inherently slow pace of designing, building, and testing these pathways in living organisms. Traditional methods require encoding pathway enzymes in DNA, inserting them into a host organism (such as E. coli or yeast), and waiting for the cells to grow and express the proteins—a process that can take six to twelve months for a single design-build-test cycle [38]. This slow iteration cycle drastically impedes progress in validating biosynthetic pathway functionality.

The iPROBE platform (in vitro Prototyping and Rapid Optimization of Biosynthetic Enzymes) represents a paradigm shift. This cell-free framework accelerates the prototyping phase from months to just weeks by moving the critical steps of pathway assembly and testing out of living cells and into a test tube [39] [38]. By leveraging cell-free protein synthesis (CFPS) and high-throughput screening, iPROBE allows researchers to rapidly explore hundreds of biosynthetic hypotheses without the constant need to re-engineer living microbes, thereby dramatically accelerating the validation of biosynthetic pathways.

Core Principles and Workflow

The iPROBE platform is built on the foundation of cell-free gene expression (CFE), which uses the transcription and translation machinery extracted from cells to synthesize proteins and run metabolic pathways in a controlled, test-tube environment [40]. This approach bypasses the constraints of cell growth, viability, and the complex regulatory networks of a living organism, offering unprecedented flexibility.

The workflow can be broken down into four key stages:

- Design and Assembly: DNA templates encoding the biosynthetic enzymes of interest are prepared. iPROBE excels at testing numerous homologs (variants from different organisms) for each enzymatic step in the pathway.

- Cell-Free Protein Synthesis: These DNA templates are added to a cell-free extract, a crude lysate containing the necessary cellular machinery (ribosomes, tRNAs, enzymes) to transcribe and translate the DNA into functional proteins [40]. This step enriches the extract with the specific enzymes required for the target pathway.

- Pathway Activation and Analysis: The enzyme-enriched extract is supplemented with buffers, salts, an energy source (like glucose), and starting substrates. The biosynthetic pathway is activated, and products are allowed to accumulate. The mixture is then analyzed using techniques like mass spectrometry to quantify pathway performance [39].

- Data-Driven Optimization: The performance data for hundreds of unique enzyme combinations are used to identify the optimal set for the desired product. This "best-performing" pathway is then implemented in a living production host.

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and the key advantage of the iPROBE platform compared to the traditional, in vivo cycle.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The iPROBE platform relies on a suite of specialized reagents and components that form the "scientist's toolkit" for cell-free prototyping. The table below details these essential materials and their functions.

Table 1: Key Research Reagent Solutions for iPROBE Experiments

| Reagent / Component | Function in the iPROBE Workflow |

|---|---|

| Cell-Free Extract | Crude lysate (e.g., from E. coli) providing the core transcriptional and translational machinery (ribosomes, tRNAs, polymerases) [39] [40]. |

| DNA Templates | Plasmids or linear DNA encoding the target biosynthetic enzymes. Multiple homologs are used for each step to screen for optimal performance [39]. |