Protein Side-Chain Conformation Prediction: Methods, Benchmarks, and Applications in Drug Discovery

Accurate prediction of protein side-chain conformations is a critical challenge in computational structural biology, with profound implications for protein design, docking, and understanding mutation effects.

Protein Side-Chain Conformation Prediction: Methods, Benchmarks, and Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

Accurate prediction of protein side-chain conformations is a critical challenge in computational structural biology, with profound implications for protein design, docking, and understanding mutation effects. This article provides a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, exploring the foundational principles of side-chain packing, from rotamer libraries to hard-sphere models. It details the evolution of methodological approaches, including Monte Carlo sampling, dead-end elimination, and modern diffusion models like PackPPI. The review systematically addresses troubleshooting for diverse residue environments and data limitations, while offering a rigorous validation of current methods against benchmarks like CASP. By synthesizing performance across soluble proteins, interfaces, and membrane environments, this resource equips scientists to select appropriate tools for applications in therapeutic design and precision medicine.

The Foundations of Protein Side-Chain Packing: From Rotamers to Structural Biology

The Critical Role of Side-Chain Conformation in Protein Function and Drug Design

Protein side-chain conformations are critically important for understanding the atomic details of biological functions, including catalysis, signaling, and molecular recognition. The precise three-dimensional arrangement of side-chain atoms determines how proteins interact with other molecules, form complexes, and perform their biological roles. Accurate prediction of side-chain conformations is essential for practical applications that require atomic-resolution models, such as rational drug design and protein engineering. Over the past decades, numerous computational methods have been developed to address the protein side-chain packing (PSCP) problem—predicting the 3D configuration of side-chain atoms given the arrangement of backbone atoms. The groundbreaking advances in protein structure prediction by AlphaFold have further accelerated this field, though significant challenges remain in achieving consistent atomic-level accuracy, particularly for alternative conformations and protein-protein interfaces [1] [2].

The side-chain conformation prediction problem is fundamentally important because protein structures determined by experimental methods like NMR spectroscopy often have more precisely defined backbone coordinates than side-chain atoms. Additionally, residues at protein-protein interfaces exhibit different conformations than the same residues in isolation, making accurate side-chain prediction crucial for modeling protein complexes and understanding allosteric regulation. With the increasing application of computational models in drug discovery and protein design, the ability to reliably predict side-chain conformations has become indispensable for advancing structural biology research and therapeutic development [3] [4].

Methodologies for Side-Chain Conformation Prediction

Computational methods for side-chain conformation prediction can be broadly categorized into three classes: rotamer library-based algorithms, probabilistic or machine learning approaches, and deep learning or generative modeling-based methods. Rotamer library-based methods leverage the observation that side-chains tend to adopt discrete sets of conformations known as rotamers. These methods typically formulate side-chain prediction as a combinatorial optimization problem, searching for the rotamer combination that minimizes the global energy of the protein structure. Popular implementations include SCWRL4, Rosetta Packer, and FASPR, which employ different search algorithms and scoring functions to identify optimal side-chain arrangements [3] [1].

More recently, deep learning-based methods have demonstrated promising results by leveraging various neural network architectures. These include DLPacker, which uses a voxelized representation of each residue's local environment with a U-net-style architecture; AttnPacker, an end-to-end SE(3)-equivariant deep graph transformer for direct prediction of side-chain coordinates; and diffusion-based approaches like DiffPack that leverage torsional diffusion models for autoregressive side-chain packing. These methods represent the state of the art in PSCP, achieving impressive accuracy when experimentally resolved backbone coordinates are used as input [1].

Performance Comparison of Prediction Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Side-Chain Prediction Methods and Their Accuracy

| Method | Approach Category | Key Features | Reported χ1 Accuracy | Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCWRL4 | Rotamer-based | Graph theory, dead-end elimination | >80% [3] | Fast, widely used |

| Rosetta Packer | Rotamer-based | Monte Carlo, energy minimization | >80% [3] | High accuracy, physically realistic |

| FASPR | Rotamer-based | Optimized scoring, deterministic search | >80% [3] | Fast, optimized scoring |

| OSCAR | Rotamer-based | Genetic algorithm, simulated annealing | >80% [3] | Flexible rotamer model |

| Sccomp | Rotamer-based | Surface complementarity, solvation | >80% [3] | Chemical similarity scoring |

| AlphaFold2/ColabFold | Deep Learning | Evoformer, attention mechanisms | ~86% χ1, ~52% χ3 [5] | End-to-end structure prediction |

| AlphaFold3 | Deep Learning | Improved architecture | Slightly better than AF2 [5] | Enhanced side-chain accuracy |

| AttnPacker | Deep Learning | Graph transformer, coordinate prediction | Varies by backbone source [1] | Direct coordinate prediction |

| DiffPack | Deep Learning | Torsional diffusion | Varies by backbone source [1] | State-of-the-art accuracy |

Table 2: Side-Chain Prediction Accuracy by Structural Environment

| Structural Environment | Prediction Accuracy | Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Buried residues | Highest accuracy [3] | Restricted conformational space |

| Protein-protein interfaces | Better than surface residues [3] | Despite limited training on complexes |

| Membrane-spanning regions | Better than surface residues [3] | Despite limited training on membrane proteins |

| Surface residues | Lower accuracy [3] | High flexibility and solvent exposure |

Experimental Protocols for Side-Chain Conformation Studies

Protocol 1: Assessment of Side-Chain Prediction Accuracy Using Native Backbones

Purpose: To evaluate the performance of side-chain prediction methods using experimentally determined backbone structures as input.

Materials:

- Experimentally determined protein structures (e.g., from PDB)

- Side-chain prediction software (SCWRL4, Rosetta, etc.)

- Computing resources appropriate for the selected methods

Procedure:

- Dataset Preparation: Select a non-redundant set of protein structures from the PDB. Ensure structures cover diverse protein folds and include various structural environments (buried, surface, interface).

- Backbone Extraction: Prepare input files containing only backbone atoms (N, Cα, C, O) for each protein, removing all side-chain atoms beyond Cβ.

- Method Execution: Run each side-chain prediction method using the backbone-only structures as input. Use default parameters for each method unless specifically testing parameter sensitivity.

- Accuracy Assessment: Compare predicted side-chain conformations with experimental structures using the following metrics:

- χ angle accuracy: Calculate the percentage of χ1, χ2, χ3, and χ4 dihedral angles predicted within specific thresholds (typically 20° or 40° of experimental values)

- Root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of side-chain heavy atoms

- Rotamer recovery rate: Percentage of residues predicted in the correct rotameric state

Notes: This protocol establishes baseline performance for each method and reveals systematic strengths and weaknesses across different amino acid types and structural environments [3].

Protocol 2: Validation of NMR Side-Chain Conformations via Packing Calculations

Purpose: To independently validate side-chain conformations in NMR-derived structures using computational packing algorithms.

Materials:

- Ensemble of NMR protein structures

- Side-chain packing software (e.g., based on rotamer libraries)

- X-ray crystal structure of the same protein (for validation)

Procedure:

- Backbone Extraction: Extract backbone coordinates from each conformer in the NMR ensemble.

- Side-Chain Prediction: Apply side-chain packing algorithms to predict side-chain conformations compatible with each NMR-derived backbone.

- Comparison: Compare the packing-predicted side-chain conformations with both the NMR models and available X-ray structures.

- Validation Metrics:

- Calculate agreement percentage between packing predictions and NMR models

- Determine how often agreement between NMR and prediction correlates with agreement with X-ray structure

- Identify questionable conformations in NMR models where predictions disagree

Notes: This approach provides independent validation for side-chain conformations in NMR structures, with reported accuracy of ~78% for confirming correct conformations and ~60% for identifying questionable conformations [4].

Protocol 3: Side-Chain Repacking on AlphaFold-Generated Structures

Purpose: To evaluate and improve side-chain conformations on protein structures predicted by AlphaFold.

Materials:

- AlphaFold-predicted protein structures

- Multiple PSCP methods (SCWRL4, Rosetta Packer, AttnPacker, DiffPack, etc.)

- Scripting environment for integrative approach

Procedure:

- Backbone Preparation: Extract backbone coordinates from AlphaFold-predicted structures.

- Confidence Score Extraction: Extract per-residue pLDDT confidence scores from AlphaFold output.

- Multiple Method Repacking: Repack side-chains using various PSCP methods with AlphaFold backbones as input.

- Integrative Refinement: Implement a confidence-aware greedy energy minimization:

- Initialize structure with AlphaFold's output

- Generate variations using different repacking tools

- Iteratively update χ angles using weighted averages based on backbone pLDDT scores

- Accept changes only when they decrease the overall energy (e.g., calculated with REF2015)

- Validation: Compare repacked structures with experimental data when available, or use internal quality metrics.

Notes: This protocol addresses the challenge that traditional PSCP methods often fail to generalize well when using AlphaFold-predicted backbones instead of experimental ones [1].

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Side-Chain Conformation Studies

| Resource | Type | Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCWRL4 | Software | Rotamer-based side-chain prediction | http://dunbrack.fccc.edu/scwrl4/ |

| Rosetta3 | Software Suite | Monte Carlo side-chain packing with energy minimization | https://www.rosettacommons.org/ |

| FoldX | Software | Side-chain modeling with energy computation | http://foldx.org/ |

| AlphaFold2/ColabFold | Software | End-to-end structure prediction including side-chains | https://github.com/deepmind/alphafold; https://github.com/sokrypton/ColabFold |

| AlphaFold3 | Software | Improved side-chain accuracy | https://alphafoldserver.com/ |

| AttnPacker | Software | Deep learning-based coordinate prediction | https://github.com/ protein-qa/AttnPacker |

| DiffPack | Software | Diffusion-based side-chain packing | https://github.com/ protein-qa/DiffPack |

| Protein Data Bank | Database | Experimental structures for training and validation | https://www.rcsb.org/ |

| Dunbrack Rotamer Library | Database | Backbone-dependent rotamer distributions | http://dunbrack.fccc.edu/bbdep2019/ |

Applications in Drug Design and Protein Engineering

Accurate side-chain conformation prediction enables critical applications in drug discovery and protein design. In structure-based drug design, precise modeling of binding site side-chains allows for more effective virtual screening and rational ligand optimization. Particularly for protein-protein interactions, which often represent challenging drug targets, the ability to predict interface side-chain conformations is essential for designing inhibitors that disrupt these interactions. Side-chain prediction methods have proven valuable for estimating binding affinities and optimizing protein-ligand interactions [3].

In protein engineering, side-chain packing algorithms facilitate the design of proteins with novel functions and modified properties. Examples include designing enzymes with altered substrate specificity, improving protein stability for industrial applications, and creating novel protein-protein interactions for therapeutic purposes. The integration of side-chain prediction with sequence-based models, such as the Potts model, enables exploration of the relationship between mutations, cooperative structural changes, and fitness, providing powerful tools for protein design [5].

Recent advances have demonstrated that integration of sequence-based Potts models with AlphaFold creates a pipeline for exploring the structural consequences of cooperative mutations on side-chain rearrangements. This approach enables large-scale mutational scans to identify strongly cooperative mutational pairs and predict their structural signatures on interacting side-chains, opening new possibilities for understanding sequence-structure-function relationships [5].

Signaling Pathways and Workflow Diagrams

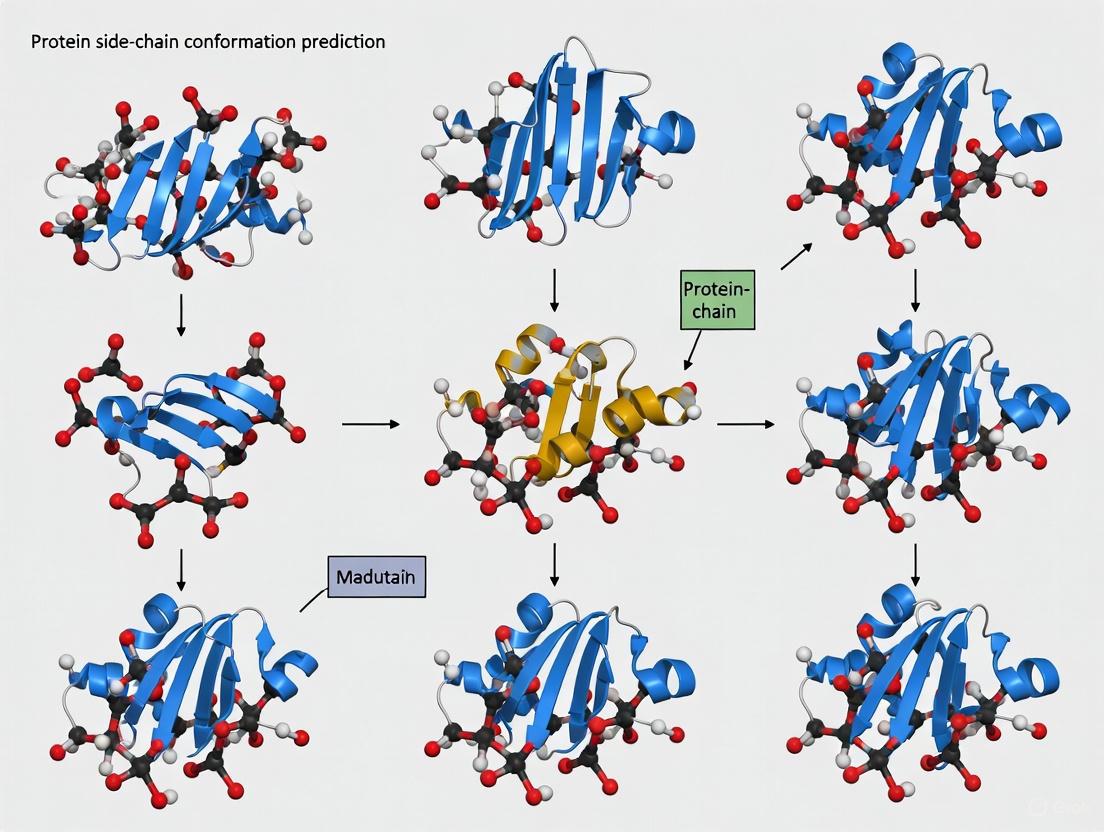

Diagram 1: Relationship between side-chain conformation and protein function. This workflow illustrates how sequence information leads to backbone and side-chain conformation prediction, ultimately enabling applications in drug design and protein engineering.

Diagram 2: Experimental workflow for side-chain conformation prediction studies. This diagram outlines the key steps in predicting and validating protein side-chain conformations using different methodological approaches.

Side-chain conformation prediction remains an active and evolving field despite decades of research. The development of AlphaFold and related deep learning methods has dramatically improved our ability to predict protein structures, but challenges in consistently achieving atomic-level accuracy for side-chains persist. Current methods perform well across diverse structural environments, including buried residues, protein interfaces, and membrane-spanning regions, often exceeding expectations given their training primarily on monomeric soluble proteins [3].

The emerging integration of physical principles with evolutionary information in methods like AlphaFold represents a promising direction. Additionally, the development of specialized approaches for predicting alternative conformations, such as Cfold, expands the applicability of these tools for understanding protein dynamics and allosteric mechanisms. As these methods continue to improve, their impact on drug discovery, protein design, and structural biology will undoubtedly grow, enabling more precise manipulation of protein function and more effective therapeutic development [6].

Future advances will likely focus on improving accuracy for surface residues, which currently show lower prediction accuracy due to their flexibility and solvent exposure, and developing better methods for predicting the side-chain conformations of protein complexes. The incorporation of explicit physical constraints with learned statistical potentials may further enhance prediction reliability, particularly for novel protein folds and engineered proteins not represented in training datasets. As these computational methods mature, they will increasingly become standard tools in structural biology and drug discovery research.

In the intricate field of protein structural biology, rotamer libraries serve as fundamental tools for classifying and predicting the conformations of amino acid side-chains. The term "rotamer" originates from "rotational isomer," describing the discrete, low-energy conformations that side-chains adopt based on rotations around their torsional (χ) angles [7]. These libraries systematically catalog the frequencies, mean dihedral angles, and standard deviations of these conformations, providing a critical foundation for computational methods in protein structure prediction, homology modeling, and protein design [8]. The development of rotamer libraries represents a pivotal advancement in addressing the combinatorial complexity of side-chain packing, as they effectively reduce the vast conformational space to a manageable set of statistically probable states observed in experimental structures or sampled through molecular dynamics simulations [7] [9].

The evolution of rotamer libraries has progressed from backbone-independent collections to more sophisticated backbone-dependent libraries that account for the profound influence of local main-chain conformation on side-chain rotamer preferences [8]. This backbone dependency arises primarily from steric repulsions between backbone atoms, whose positions are determined by the φ and ψ dihedral angles of the Ramachandran map, and the side-chain γ heavy atoms (e.g., CG, OG, SG) [8]. These steric interactions create predictable patterns where certain rotamers become energetically unfavorable at specific backbone conformations, leading to the observed backbone dependence of rotamer populations [8]. The implementation of backbone-dependent rotamer libraries has significantly enhanced the accuracy and efficiency of side-chain prediction algorithms, establishing them as an indispensable component in the computational structural biologist's toolkit [9] [8].

Backbone-Dependent Rotamer Libraries: Core Principles and Development

Historical Development and Theoretical Foundation

The conceptual foundation for backbone-dependent rotamer libraries was established in 1993 when Roland Dunbrack developed the first comprehensive library to assist in predicting side-chain Cartesian coordinates given experimentally determined or predicted main-chain coordinates [8]. This pioneering library was derived from statistical analysis of 132 high-resolution protein structures from the Protein Data Bank, organizing the counts and frequencies of χ1 or χ1+χ2 rotamers for 18 amino acids (excluding glycine and alanine) across 20° × 20° bins of the Ramachandran map [8]. The theoretical underpinning of this approach recognizes that side-chain conformations are not independent of their structural context but are significantly constrained by the local backbone geometry through quantum mechanical and steric effects [9] [8].

A substantial advancement came in 1997 when Dunbrack and Cohen introduced a Bayesian statistical framework for rotamer library construction, enabling more robust probability estimates by incorporating a prior distribution that assumed independent effects of φ and ψ dihedral angles [8]. This Bayesian approach utilized a periodic kernel with 180° periodicity, similar to a von Mises distribution, to smoothly account for side-chain observations across bin boundaries [8]. Further refinement occurred in 2011 with the development of a smoothed backbone-dependent rotamer library employing kernel density estimates and kernel regressions with von Mises distribution kernels, creating continuous probability functions with smooth derivatives essential for mathematical optimization algorithms used in protein design [8]. This evolution from discrete binning to continuous probability distributions represents the increasing sophistication in modeling the complex relationship between backbone conformation and side-chain rotamer preferences.

Molecular Basis of Backbone Dependence

The fundamental mechanism underlying backbone-dependent rotamer preferences stems from steric repulsions between backbone atoms and side-chain heavy atoms. These interactions occur in predictable combinations dependent on the dihedral angles connecting the backbone to the side-chain atoms [8]. Specifically, steric clashes arise when the connecting dihedral angles form specific pairs of values ({-60°,+60°} or {+60°,-60°}) due to a phenomenon related to pentane interference [8].

Table: Backbone-Dependent Steric Interactions for χ1 Rotamers

| Rotamer | N(i+1) Interaction | O(i) Interaction | C(i-1) Interaction | HBond to NH(i) Interaction |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| g+ | ψ = -60° | ψ = +120° | φ = +60° | φ = -120° |

| trans | ψ = 180° | ψ = 0° | - | - |

| g- | - | - | φ = -180° | φ = 0° |

These steric constraints create distinct population patterns observable in Ramachandran plots, where certain rotamers exhibit significantly reduced frequencies at specific φ,ψ combinations [8]. For example, valine exhibits unique behavior among amino acids due to its two γ heavy atoms (CG1 and CG2), which simultaneously interact with the backbone across different χ1 rotamers. This dual interaction explains why valine predominantly adopts the trans rotamer (χ1~180°) across most backbone conformations, unlike other residues [8]. Understanding these molecular principles enables more accurate prediction of side-chain conformations and informs the development of improved energy functions for protein modeling.

Quantitative Analysis of Rotamer Libraries

The effectiveness of rotamer libraries in computational protein modeling can be quantitatively assessed through various statistical measures and performance metrics. Backbone-dependent rotamer libraries typically provide frequency distributions, mean dihedral angles, and standard deviations for each rotamer across different regions of the Ramachandran map [8]. These statistical parameters enable the calculation of probabilistic energy terms (often formulated as E = -ln(p(rotamer(i) | φ,ψ))) that guide side-chain packing algorithms toward biophysically realistic conformations [8].

Performance benchmarking of side-chain packing methods utilizing different rotamer libraries reveals significant differences in accuracy. Traditional metrics include χ angle accuracy (the percentage of correctly predicted χ angles within a specified tolerance, typically 20°-40°) and root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of side-chain atomic positions from native structures [10] [11] [9]. Studies have demonstrated that methods employing backbone-dependent rotamer libraries, such as SCWRL, achieve approximately 74% accuracy for χ1 and 60% for χ1+χ2 angles when placing side-chains on their native backbones, approaching the theoretical limits imposed by experimental uncertainty in the underlying structural data [9]. In more challenging homology modeling scenarios where side-chains are placed on non-native backbones, accuracy decreases to approximately 65% for χ1 and 45% for χ1+χ2 angles, yet still represents a significant improvement over backbone-independent approaches [9].

Table: Performance Comparison of Protein Side-Chain Packing Methods

| Method | Approach | χ1 Accuracy (%) | Runtime (Relative) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SCWRL4 | Rotamer library-based | ~74 | 1x | Backbone-dependent rotamers, graph theory |

| Rosetta Packer | Rotamer library-based | ~76 | 1000x | Monte Carlo minimization, full-atom energy function |

| FASPR | Rotamer library-based | ~75 | 1.5x | Fast search algorithm, optimized scoring |

| AttnPacker | Deep learning | ~79 | 10x | SE(3)-equivariant transformer, no rotamer library |

| DLPacker | Deep learning | ~72 | 100x | Voxelized environment, U-net architecture |

| DiffPack | Deep learning | ~78 | 500x | Torsional diffusion model, generative approach |

Recent large-scale benchmarking in the post-AlphaFold era reveals that while traditional rotamer-based methods perform well with experimental backbone inputs, they often struggle to maintain accuracy when repacking side-chains on AlphaFold-predicted backbone structures [10]. This challenge has prompted the development of hybrid approaches that integrate confidence metrics from AlphaFold (such as pLDDT) with rotamer-based packing algorithms to improve performance on predicted structures [10].

Experimental Protocols for Rotamer Analysis

Protocol 1: Rotamer Dynamics Analysis from MD Simulations

The analysis of rotamer dynamics (RD) from molecular dynamics (MD) simulations provides insights into side-chain conformational flexibility in solution environments, complementing static observations from crystal structures [7]. The following protocol outlines a method for extracting and classifying rotamers from MD trajectories:

Step 1: MD Simulation Setup and Execution

- Perform MD simulations using packages such as AMBER, GROMACS, or CHARMM with appropriate force fields and solvation parameters [7].

- For the example system described in [7], implicit water MD simulations of protein-peptide complexes (e.g., pNGF peptide with TrkA receptor) were conducted using the sander module in AMBER 14 with protonation states optimized for physiological pH (7.4) [7].

Step 2: Trajectory Processing and Frame Extraction

- Convert the trajectory file to PDB format using trajectory processing tools (e.g., cpptraj module in AMBER) [7].

- Extract and save individual frames as separate PDB files to enable sequential analysis of each conformation sampled during the simulation [7].

Step 3: Torsional Angle Calculation

- Calculate torsional angles for each residue across all frames using structural analysis tools (e.g., Bio3D module in R) [7].

- The Bio3D module is particularly efficient as it requires only residue definition rather than manual specification of the four atoms defining each dihedral angle [7].

- Transform the data to organize angle values (columns) by simulation frames (rows) for subsequent analysis [7].

Step 4: Rotamer Classification

- Classify the calculated torsional angles into specific rotamers using a reference library (e.g., the penultimate rotamer library) [7].

- Implement classification rules using conditional (if/else) statements based on the angular ranges defined in the rotamer library [7].

- The penultimate rotamer library is particularly suitable for this analysis due to its backbone independence, countable number of rotamers, and simple nomenclature (e.g., ptp rotamer for Methionine indicates p for χ1, t for χ2, and p for χ3) [7].

Step 5: Data Visualization and Interpretation

- Generate graphical representations of rotamer distributions and transitions over the simulation timeframe [7].

- Analyze rotamer-rotamer relationships, correlations with secondary structure elements, and flexibility metrics for functional interpretation [7].

Diagram 1: Workflow for rotamer dynamics analysis from MD simulations illustrating the five major protocol steps and required resources.

Protocol 2: Side-Chain Prediction with SCWRL for Homology Modeling

SCWRL (Side-Chains With a Rotamer Library) employs a backbone-dependent rotamer library to efficiently predict side-chain conformations in homology modeling [9]. The algorithm operates through the following methodological steps:

Step 1: Input Structure Preparation

- Obtain main-chain atom coordinates (N, Cα, C, O) from an experimentally determined structure or homology model [9].

- For homology modeling, ensure proper alignment between target sequence and template structure [9].

Step 2: Initial Rotamer Placement

- Assign the most probable rotamer from a backbone-dependent rotamer library to each residue position based on its local φ and ψ angles [9].

- Use the Dunbrack backbone-dependent rotamer library, which provides rotamer probabilities conditional on backbone conformation [9] [8].

Step 3: Steric Clash Detection

- Identify steric clashes between initially placed side-chains using a modified van der Waals energy function [9].

- Define clashes based on atomic overlap beyond tolerated distances [9].

Step 4: Combinatorial Search for Clash Resolution

- For residues involved in steric clashes, perform a combinatorial search through alternative rotamer assignments [9].

- Search order is prioritized by rotamer probabilities from the library and the severity of steric interactions [9].

- Implement efficient pruning strategies to reduce the combinatorial complexity of the search space [9].

Step 5: Final Model Output

- Output the final model with optimized side-chain conformations in standard PDB format [9].

- Validation metrics may include calculation of χ angle accuracies and RMSD when native structures are available for comparison [9].

Diagram 2: SCWRL algorithm workflow for side-chain prediction showing the sequential process from input preparation to final model generation.

Table: Essential Resources for Rotamer Library Research and Application

| Resource Name | Type | Function/Application | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dunbrack Rotamer Library | Backbone-dependent rotamer library | Provides probabilities and mean angles for side-chain conformations dependent on backbone φ,ψ angles | http://dunbrack.fccc.edu/rotlib/ |

| Penultimate Rotamer Library | Backbone-independent rotamer library | Classification of rotamers with simple nomenclature; useful for MD analysis | Richardson Lab (Duke University) |

| SCWRL4 | Software tool | Fast side-chain prediction using graph theory and backbone-dependent rotamers | http://dunbrack.fccc.edu/scwrl/ |

| Rosetta/PyRosetta | Software suite | Protein structure prediction and design with Monte Carlo rotamer packing | https://www.rosettacommons.org/ |

| AttnPacker | Deep learning tool | SE(3)-equivariant transformer for side-chain packing without discrete rotamer sampling | https://github.com/ protein-qa/AttnPacker |

| AMBER with cpptraj | MD software and analysis | MD simulations and trajectory processing for rotamer dynamics studies | https://ambermd.org/ |

| Bio3D (R package) | Analysis tool | Extraction of torsional angles from protein structures for rotamer classification | https://cran.r-project.org/package=bio3d |

| Dynameomics Library | MD-derived rotamer library | Rotamer distributions from molecular dynamics simulations | Daggett Lab (University of Washington) |

Advanced Applications and Future Directions

Emerging Deep Learning Approaches

The field of protein side-chain packing is undergoing a significant transformation with the emergence of deep learning methods that challenge traditional rotamer-based approaches. Methods such as AttnPacker employ SE(3)-equivariant transformer architectures to directly predict side-chain coordinates without delegating to discrete rotamer libraries or performing expensive conformational sampling [11]. These approaches demonstrate several advantages, including significantly improved computational efficiency (over 100× faster than some traditional methods), reduced steric clashes, and enhanced accuracy on both native and non-native backbone structures [11]. Unlike rotamer-based methods that select from predefined conformations, deep learning approaches can explore a continuous conformational space, potentially capturing novel side-chain arrangements beyond those cataloged in existing libraries [10] [11].

Other innovative deep learning architectures include DiffPack, which leverages torsional diffusion models for autoregressive side-chain packing, and FlowPacker, which employs torsional flow matching with continuous normalizing flow models [10]. These generative approaches represent the cutting edge of side-chain conformation prediction, achieving impressive accuracy when experimental backbone coordinates are used as input [10]. However, benchmarking studies reveal that these methods, like their traditional counterparts, face challenges in maintaining accuracy when processing AlphaFold-predicted backbone structures rather than experimental ones [10]. This limitation highlights the ongoing need for improved methods that can effectively leverage predicted protein structures from tools like AlphaFold2 and AlphaFold3.

Continuous Rotamers in Protein Design

The concept of continuous rotamers represents another significant advancement beyond traditional discrete rotamer libraries. Rather than representing each side-chain conformation as a single discrete state, continuous rotamer models allow side-chains to explore the continuous conformational space around low-energy regions [12]. This approach addresses a fundamental limitation of rigid rotamer models: the inability to account for small conformational adjustments that can resolve steric clashes and optimize packing interactions without completely changing rotameric state [12].

Research has demonstrated that protein design using continuous rotamers produces sequences that are more similar to native sequences and have lower energies compared to those obtained through rigid rotamer models [12]. Importantly, simply increasing the sampling of discrete rotamers within the continuous space does not provide a practical alternative to true continuous rotamer models, as computationally feasible sampling densities consistently yield higher energies than continuous approaches [12]. Algorithms such as iMinDEE (improved Minimized Dead-End Elimination) have been developed to make continuous rotamer search feasible for larger systems, providing guarantees of finding the optimal solution while maintaining computational efficiency comparable to discrete DEE algorithms [12]. These advances in continuous rotamer methods highlight the importance of modeling realistic protein flexibility in computational design, with significant implications for applications in enzyme design, drug discovery, and protein therapeutics.

Challenges in the Post-AlphaFold Era

Despite remarkable progress in protein structure prediction through AlphaFold, significant challenges remain for rotamer-based methods in the post-AlphaFold era. Large-scale benchmarking reveals that traditional protein side-chain packing methods perform well with experimental backbone inputs but struggle to generalize when repacking side-chains on AlphaFold-generated structures [10]. This performance gap persists even when integrating AlphaFold's self-assessment confidence scores (pLDDT) into the packing process [10]. While confidence-aware integrative approaches can yield modest improvements over AlphaFold's native side-chain predictions, these gains are often statistically insignificant and lack consistency across different targets [10].

These limitations underscore the need for next-generation side-chain packing methods specifically optimized for predicted backbone structures rather than experimental ones. Future directions may include the development of end-to-end deep learning approaches that jointly predict backbone and side-chain conformations, hybrid methods that combine physical principles with learned statistical preferences, and rotamer libraries specifically derived from AlphaFold-predicted structures to capture any systematic biases in these models. As the structural coverage of the protein universe expands through computational prediction rather than experimental determination, the evolution of rotamer libraries and side-chain packing methods will continue to play a crucial role in translating these structural models into biologically meaningful insights for drug development and protein engineering.

Protein function is intimately tied to the three-dimensional arrangement of its structure, with side-chain conformations playing a critical role in molecular interactions, binding specificity, and catalytic activity [13] [14]. While the protein backbone provides the structural framework, the side chains confer functional diversity through their chemical properties and spatial arrangements. Understanding side-chain conformational diversity is therefore essential for research in protein engineering, drug discovery, and structural biology.

Traditional structural biology often depicts proteins as static entities, yet in reality, side chains exhibit significant dynamic behavior [13]. This article systematizes side-chain conformations into four distinct categories—fixed, discrete, cloud, and flexible—based on extensive analysis of experimental data from X-ray crystallography and cryo-EM studies. This classification provides researchers with a framework for interpreting structural data, predicting functional mechanisms, and designing experiments that account for protein dynamics.

The accurate prediction of these conformational states remains a formidable challenge in computational structural biology. While advances in deep learning, such as AlphaFold2, have revolutionized protein structure prediction, limitations persist in capturing the full spectrum of side-chain dynamics, particularly for alternative conformations [15] [6] [16]. This article details experimental protocols for characterizing side-chain conformations and discusses their implications for structure-based drug design.

Classification of Side-Chain Conformations

Based on comprehensive analysis of electron density maps and structural variability in the Protein Data Bank, side-chain conformations can be systematically categorized into four distinct types [13]. Each type represents a different mode of structural flexibility with implications for protein function and molecular recognition.

Fixed Conformations

Fixed conformations represent side chains constrained to a single, well-defined spatial arrangement. These residues are typically buried within the protein core or tightly involved in specific structural motifs, where their movements are restricted by extensive packing interactions with neighboring atoms [17] [13].

Characteristics:

- Electron density maps show clear, continuous density for all side-chain atoms

- No significant alternative locations observed in crystallographic data

- Low B-factors (temperature factors) indicating minimal vibrational motion

- Typically found in hydrophobic cores or specific binding sites where precise positioning is functionally critical

Functional significance: Fixed side chains often contribute to protein stability through hydrophobic interactions or serve as critical components in catalytic sites where precise geometry is essential for function. Their constrained nature makes them highly predictable in structure modeling approaches.

Discrete Conformations

Discrete conformations occur when a side chain adopts two or more distinct, well-defined spatial arrangements. These alternative states are often stabilized by different molecular environments or represent intermediate states in functional mechanisms [13].

Characteristics:

- Electron density maps reveal separate, distinct densities for the same side chain

- Documented as alternate locations (e.g., 'A' and 'B') in PDB files with specific occupancy values

- Each discrete state has clear electron density support

- Transitions between states may occur in response to ligand binding or environmental changes

Functional significance: Discrete conformations are frequently observed in proteins with allosteric regulation, enzyme active sites with multiple substrate specificities, and molecular switches. They enable proteins to adopt different functional states without major backbone rearrangements.

Cloud Conformations

Cloud conformations describe side chains that occupy a continuous region of space rather than discrete positions. The electron density suggests a dynamic equilibrium between multiple similar states or a single state with substantial spatial fluctuation [13].

Characteristics:

- Electron density maps show broad, continuous regions of density covering more area than a single atom would occupy

- Often represented as a single conformational model with elevated B-factors

- Occupancy values may sum to 1.0 but represent an average across multiple similar states

- More common in longer side chains with multiple rotatable bonds

Functional significance: Cloud conformations provide a mechanism for entropy-driven processes and enable structural adaptability in molecular recognition. They may serve as intermediate states in conformational selection mechanisms or facilitate binding to multiple partners with slightly different geometries.

Flexible Conformations

Flexible conformations represent side chains with high mobility that cannot be precisely determined from experimental electron density maps. These residues lack clear electron density for some or all of their side-chain atoms, indicating either dynamic disorder or multiple highly divergent conformations [13].

Characteristics:

- Incomplete or absent electron density for side-chain atoms even at moderate resolutions

- High B-factors indicating significant thermal motion

- Often found in surface-exposed regions or flexible loops

- May represent genuinely disordered states that only become ordered upon binding

Functional significance: Flexible side chains are common in protein-protein interaction interfaces, ligand-binding sites that accommodate multiple substrates, and intrinsically disordered regions. Their conformational entropy can contribute significantly to binding thermodynamics and specificity.

Table 1: Characteristics of the Four Side-Chain Conformation Types

| Conformation Type | Electron Density Pattern | B-Factor Range | Structural Context | Predictability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed | Clear, continuous density for all atoms | Low | Buried cores, active sites | High |

| Discrete | Separate distinct densities | Variable between states | Allosteric sites, molecular switches | Moderate |

| Cloud | Broad, continuous density | Moderate to high | Surface regions, binding interfaces | Low to moderate |

| Flexible | Weak or absent density | High | Surface loops, disordered regions | Low |

Quantitative Analysis of Conformational Variations

Systematic analysis of protein structures reveals distinct patterns in side-chain conformational variability across different environments and residue types. Understanding these quantitative relationships is essential for accurate interpretation of structural data and improvement of prediction algorithms.

Environmental Influence on Conformational Flexibility

The protein environment significantly influences side-chain conformational preferences. Statistical analyses demonstrate that 71% of protein complexes exhibit Cα RMSD < 2Å between bound and unbound forms, indicating that side-chain rearrangements often dominate binding-induced conformational changes [17]. Core residues demonstrate significantly smaller conformational changes compared to surface residues, with the average root-square deviation of dihedral angles (RSD) for interface residues increasing from 40.5° for residues with one dihedral angle to 135.0° for residues with four dihedral angles [17].

Solvent accessibility strongly correlates with conformational flexibility. Quantitative studies show that approximately 72% of surface residues have reliable side-chain atom coordinates in high-resolution structures, compared to over 90% of core residues [13]. This environmental influence extends to binding interfaces, where conformational changes upon complex formation increase both polar and nonpolar surface areas, with a disproportionately larger increase in nonpolar area across all classes of protein complexes [17].

Residue-Specific Conformational Propensities

Different amino acids exhibit distinct tendencies for conformational variability based on their chemical properties and side-chain topology:

Long side chains (e.g., Arg, Lys, Glu) with three or more dihedral angles frequently undergo large conformational transitions (~120° χ angle changes) and are more likely to adopt discrete or cloud conformations [17]. These residues account for the majority of significant conformational changes observed in protein-protein associations.

Short side chains (e.g., Val, Ile, Phe) with one or two dihedral angles typically undergo local readjustments (~40° RSD) rather than full rotamer transitions [17]. These residues more commonly adopt fixed conformations, particularly when buried.

Aromatic and charged residues (Phe, Tyr, Asp, Glu) show distinct patterns where the χ angle closest to the backbone often changes most significantly, contrary to the general trend where the most distant dihedral angle shows largest changes [17].

Table 2: Side-Chain Conformational Statistics by Residue Type

| Residue Type | Average RSD (°) | Preferred Conformation Types | Interface Propensity |

|---|---|---|---|

| Arginine (Arg) | 135.0° | Discrete, Cloud | High |

| Lysine (Lys) | 135.0° | Discrete, Cloud | High |

| Methionine (Met) | 135.0° | Cloud, Flexible | Moderate |

| Glutamate (Glu) | 111.3° | Discrete, Cloud | High |

| Aspartate (Asp) | 55.1° | Fixed, Discrete | High |

| Phenylalanine (Phe) | 40.5° | Fixed, Discrete | High |

| Valine (Val) | 40.5° | Fixed | Moderate |

| Cysteine (Cys) | 40.5° | Fixed | Low |

Experimental Protocols for Conformational Analysis

Electron Density Map Analysis Protocol

Purpose: To classify side-chain conformations based on experimental electron density maps from X-ray crystallography.

Materials:

- High-resolution crystal structure (≤2.5Å recommended)

- Structure factors file (.mtz format)

- Molecular graphics software (Coot, PyMOL, or Chimera)

- Electron density visualization tools

Procedure:

- Load the refined structural model and corresponding electron density map (2mFo-DFc map) into molecular graphics software

- Set the electron density contour level to 1.0σ for initial assessment

- Systematically examine each residue, adjusting contour levels to detect weak density (0.5-0.7σ)

- Classify side chains according to the following electron density characteristics:

- Fixed: Continuous density for all atoms at 1.0σ with no significant disconnected density

- Discrete: Separate distinct densities for the same side chain, often with assigned alternate locations

- Cloud: Broad, continuous density covering more space than individual atoms would occupy

- Flexible: Incomplete or absent density for some side-chain atoms at 0.5σ

- Record occupancy values for residues with alternate locations

- Calculate electron density values for each atom using map statistics

- Correlate conformational classifications with B-factors and solvent accessibility

Interpretation: Residues with reliable electron density (>1σ in 2mFo-DFc map) for all side-chain atoms can be confidently modeled. Atoms with density <1σ indicate flexibility or disorder. Approximately 81.6% of residues in high-resolution structures show reliable density for all atoms [13].

Conformational Variability Assessment Protocol

Purpose: To quantify side-chain conformational variations across multiple structures of the same protein.

Materials:

- Multiple crystal structures of the same protein (same or different conditions)

- Structure alignment software (PyMOL, Chimera, or custom scripts)

- Dihedral angle calculation tools

- Rotamer library reference

Procedure:

- Collect multiple structures of the same protein from the PDB

- Align structures using backbone Cα atoms to minimize RMSD

- Calculate side-chain dihedral angles (χ1, χ2, χ3, χ4) for each residue in all structures

- Identify residues with significant dihedral angle variations (>40° for χ1, >60° for later χ angles)

- Calculate root-square deviation (RSD) of dihedral angles for variable residues:

[ RSD = \sqrt{\frac{1}{N}\sum{i=1}^{N}(\chi{i,bound} - \chi_{i,unbound})^2} ]

- Correlate conformational changes with structural context (interface vs. core, ligand binding, etc.)

- Classify variable residues into discrete, cloud, or flexible categories based on the pattern of variation

Interpretation: Residues showing consistent dihedral angles across structures suggest fixed conformations. Those with discrete clusters of angles indicate discrete conformations, while continuous distributions suggest cloud conformations. On average, interface residues show RSD values of 40.5-135.0° depending on side-chain length [17].

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for side-chain conformation classification

Computational Prediction of Side-Chain Conformations

AI-Based Structure Prediction Accuracy

Recent advances in deep learning have revolutionized protein structure prediction, yet significant challenges remain in accurately predicting side-chain conformations. AlphaFold2 and its implementations such as ColabFold achieve varying accuracy across different dihedral angles [15]:

- χ1 angles: ~14% prediction error on average

- χ3 angles: Error increases to ~48% on average

- χ4 angles: Highest error rates due to increased flexibility

Non-polar side chains demonstrate higher prediction accuracy than polar residues, and the use of structural templates improves χ1 prediction by approximately 31% on average [15]. However, these methods exhibit bias toward the most prevalent rotamer states in the PDB, limiting their ability to capture rare conformations effectively.

Alternative Conformation Prediction Methods

Novel approaches specifically target the prediction of alternative side-chain conformations:

Cfold: This AlphaFold2-derived network trained on conformationally split PDB data successfully predicts over 50% of experimentally known nonredundant alternative conformations with high accuracy (TM-score > 0.8) [6]. Two primary sampling strategies enable this capability:

- MSA Clustering: Sampling different subsets of the multiple sequence alignment to generate diverse coevolutionary representations

- Dropout: Using dropout at inference time to exclude different information randomly from each prediction

Deep Generative Models (DGMs): Variational autoencoders, generative adversarial networks, and diffusion models learn parametric models of the equilibrium distribution of protein conformations, enabling rapid generation of diverse structural samples [18]. These approaches effectively explore conformational landscapes that are prohibitively expensive to access with conventional molecular dynamics simulations.

Table 3: Computational Methods for Side-Chain Conformation Prediction

| Method | Strengths | Limitations | Best Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold2/ColabFold | High overall accuracy, fast prediction | Bias toward common rotamers, limited alternative conformations | Single-state prediction of stable structures |

| Cfold | Specialized for alternative conformations, uses conformational splits | Requires specific training, limited to seen conformation types | Proteins with known multiple states |

| Deep Generative Models | Samples full conformational landscape, physics-informed | Computationally intensive, training data requirements | Exploring conformational diversity, flexible regions |

| Molecular Dynamics | Physically realistic dynamics, environmental effects | Extremely computationally expensive, limited timescales | Detailed mechanistic studies of specific systems |

Figure 2: Computational workflow for predicting side-chain conformations

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Side-Chain Conformational Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Application Context | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| High-resolution Crystal Structures | Experimental reference for conformation classification | All conformational studies | Provides electron density maps, B-factors, occupancy data |

| AlphaFold2/ColabFold | AI-based structure prediction | Initial structure modeling, single-state prediction | Fast prediction, high accuracy for common conformations |

| Cfold | Alternative conformation prediction | Proteins with known multiple states | Specialized for conformational diversity, uses structural partitions |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Sampling conformational landscape | Detailed dynamics studies, flexible regions | Physically realistic simulation, environmental effects |

| Rotamer Libraries | Reference for preferred side-chain conformations | Structure validation, prediction | Statistics-based probabilities, backbone-dependent preferences |

| Cryo-EM Structures | Alternative to crystallography for conformation analysis | Large complexes, flexible proteins | Captures near-native states, different conformational preferences |

Applications in Drug Discovery

Understanding side-chain conformational diversity has profound implications for structure-based drug design. Each conformation type presents distinct challenges and opportunities for therapeutic development:

Fixed conformations provide well-defined targets for drug design, enabling precise optimization of complementary interactions. These residues are ideal for anchoring specific interactions in binding pockets.

Discrete conformations require consideration of multiple binding modes or the design of conformation-selective compounds that stabilize specific functional states. Allosteric modulators often target residues with discrete conformations to lock proteins in active or inactive states.

Cloud conformations present challenges for traditional structure-based design but offer opportunities for designing compounds that exploit conformational entropy or induce conformational selection.

Flexible conformations in binding sites may necessitate dynamic docking approaches or the design of compounds that can accommodate structural heterogeneity.

Recent studies indicate that incorporating conformational diversity into drug discovery pipelines improves success rates, particularly for targets with known conformational heterogeneity. Experimental protocols for classifying side-chain conformations enable researchers to identify critical flexible residues that contribute to binding and specificity.

The classification of side-chain conformations into fixed, discrete, cloud, and flexible categories provides a valuable framework for understanding protein function and guiding structure-based drug design. Experimental protocols for conformational analysis enable researchers to accurately characterize these states, while computational methods continue to advance in their ability to predict conformational diversity.

As structural biology continues to recognize the importance of protein dynamics, accounting for side-chain conformational heterogeneity will become increasingly critical for explaining biological mechanisms and designing effective therapeutics. The integration of experimental data with improved computational sampling techniques promises to enhance our ability to predict and exploit the full conformational landscape of protein side chains in pharmaceutical applications.

Within the field of computational structural biology, the prediction of protein side-chain conformations is a critical task for applications ranging from protein design and docking to understanding the effects of mutations [3] [13]. Despite decades of research, two fundamental challenges persistently limit prediction accuracy: the combinatorial explosion of possible conformations and the limitations of current energy functions to accurately score them [3] [19]. This Application Note dissects these core challenges, provides quantitative data on their impact, and outlines detailed protocols for researchers to benchmark and improve their side-chain prediction methodologies, particularly for difficult cases like surface residues.

The Combinatorial Problem in Side-Chain Packing

Nature of the Problem

The combinatorial problem arises because each amino acid side-chain can adopt multiple low-energy conformations known as rotamers [3]. The task of selecting the optimal rotamer for every residue in a protein, such that the overall energy is minimized and no atomic clashes occur, becomes a problem of immense scale. The total number of possible combinations grows exponentially with the number of residues. For a protein with N residues, each having an average of R rotamers, the total conformational space to search is on the order of RN. This makes an exhaustive search computationally intractable for all but the smallest proteins [3].

Algorithmic Strategies and Their Limitations

To tackle this, developers have employed a range of optimization algorithms. Table 1 summarizes the primary strategies used by various prediction methods.

Table 1: Search Algorithms in Side-Chain Prediction Methods

| Method | Primary Search Algorithm | Key Features and Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| SCWRL4 [3] | Graph Decomposition & Dead-End Elimination (DEE) | Represents residue interactions as a graph; uses DEE to prune rotamers that cannot be part of the global minimum energy conformation. Efficient for many proteins but can struggle with highly connected networks. |

| Rosetta-fixbb [3] | Monte Carlo (MC) | Initializes multiple runs with random structures; uses MC sampling to find low-energy states. Can escape local minima but offers no guarantee of finding the global minimum. |

| OSCAR [3] | Genetic Algorithm & Simulated Annealing | Uses a population of structures, applies crossover and mutation operations. Good for exploring diverse regions of conformational space, but computationally intensive. |

| Sccomp-I [3] | Iterative Greedy Optimization | Builds side-chains sequentially in order of neighbor count. Fast but highly sensitive to the initial build order, leading to suboptimal solutions. |

| Sccomp-S [3] | Stochastic (Boltzmann) Sampling | Chooses rotamers based on a Boltzmann distribution. Better at modeling conformational diversity but may not converge to the single lowest-energy state. |

| RASP [3] | Hybrid (DEE + Branch-and-Terminate/MC) | Applies DEE first to reduce search space, then solves remaining problem with exact or stochastic methods. Balances efficiency and thoroughness. |

The following diagram illustrates the typical decision workflow and algorithmic strategies employed to manage the combinatorial complexity of side-chain packing.

Figure 1: Algorithmic strategies to solve the combinatorial problem in side-chain prediction. DEE, Graph Decomposition, Monte Carlo, Genetic Algorithms, and Iterative methods are used to navigate the vast conformational space.

Limitations of Energy Functions

Components of Energy Functions

Even with a perfect search algorithm, prediction accuracy is ultimately limited by the quality of the energy function used to score conformations. Most force fields are a weighted sum of several terms, which typically include [3] [19]:

- Van der Waals forces: Attractive and repulsive atomic interactions.

- Hydrogen bonding: Directional interactions critical for polar residues.

- Solvation effects: Models for interactions with the solvent environment.

- Electrostatics: Interactions between charged groups.

- Torsional potentials: Preferences for certain dihedral angles based on rotamer libraries.

A significant challenge is that these energy terms are often inexact and poorly balanced. For instance, inaccuracies in modeling solvation and entropic effects are a major source of error, especially for surface residues which are highly exposed to solvent [19].

The Entropy Challenge and the Colony Energy Solution

Surface side-chains are more flexible and have higher conformational entropy than buried residues. Traditional energy functions that focus solely on enthalpy (e.g., van der Waals and hydrogen bonding) fail to capture this entropy, leading to poor prediction accuracy for surface residues [19].

The colony energy approach is a phenomenological method developed to address this limitation by approximating entropic effects [19]. It favors rotamers located in densely populated, low-energy regions of conformational space, effectively smoothing the potential energy landscape. The colony energy Gi for a rotamer i is calculated as:

Gi = -RT * ln[ Σj exp( -Ej/(RT) - β(RMSDij/RMSDavg)γ ) ]

where Ej is the conformational energy of rotamer j, the sum is over all rotamers of the residue, and RMSDij is the heavy-atom root-mean-square deviation between rotamers i and j [19]. The use of colony energy has been shown to improve χ1 prediction accuracy for surface side-chains from 65% to 74% [19].

Quantitative Assessment of Prediction Accuracy

The interplay of the combinatorial problem and energy function limitations results in variable prediction accuracy across different residue environments and types. The data in Table 2 and Table 3, compiled from large-scale assessments, quantify these performance disparities.

Table 2: Side-Chain Prediction Accuracy by Structural Environment [3]

| Structural Environment | χ1 Angle Accuracy (≈ within 40°) | Key Challenges |

|---|---|---|

| Buried | Highest (~90% for χ1 in high-pLDDT AF2 models [15]) | Fewer rotamers, high packing density. Steric clashes are the primary concern. |

| Protein Interface | Better than surface residues | Geometry is constrained by partner protein, simplifying the problem. |

| Membrane-Spanning | Better than surface residues | Lipid bilayer imposes constraints on side-chain orientations. |

| Surface | Lowest (e.g., 73-82% for χ1 [19]) | High flexibility, solvent interactions, and inaccurate entropy modeling. |

Table 3: Side-Chain Prediction Error by Dihedral Angle and Residue Type (Example Data from ColabFold) [15]

| Amino Acid | χ1 Error (%) | χ2 Error (%) | χ3 Error (%) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| All Residues | ~14-17% (with/without templates) | N/A | ~47-50% (with/without templates) | Accuracy decreases for higher χ angles [15]. |

| Non-polar | Lower error | N/A | N/A | Easier to predict due to dominant van der Waals interactions. |

| Polar (General) | Higher error | N/A | N/A | Difficult due to hydrogen bonding and solvent interactions. |

| Polar (H-bonded) | 79% Accuracy [19] | N/A | N/A | Defined H-bond partners greatly improve prediction. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Side-Chain Prediction Methods

Objective: To quantitatively evaluate and compare the performance of different side-chain prediction methods on a set of high-resolution protein structures.

Materials:

- Software: SCWRL4, Rosetta-fixbb, FoldX, OSCAR, or other methods [3].

- Dataset: A curated non-redundant set of high-resolution (<2.0 Å) crystal structures from the PDB. The set should include monomeric, multimeric, and membrane proteins to test generality [3] [20].

- Computing Environment: Linux-based high-performance computing cluster.

Procedure:

- Dataset Preparation:

- Download your selected PDB structures.

- Remove all heteroatoms (water, ions, ligands) and alternate conformations to create a clean input structure.

- Generate the "native" backbone structure by stripping all side-chains beyond Cβ.

Run Predictions:

- For each method and each protein, input the native backbone and predict the side-chain conformations.

- Use each software's default parameters unless specifically testing parameter sensitivity.

Accuracy Calculation:

- Compare the predicted structure to the original experimental structure.

- For each residue, calculate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of heavy side-chain atoms and the deviation of dihedral angles (χ1, χ2, etc.).

- A χ angle is typically considered correctly predicted if it is within 40° of the experimental value [15] [19].

- Calculate the percentage of correctly predicted χ angles (% within 40°) for the entire protein and for subgroups: buried vs. surface, by amino acid type, etc. [3] [19].

Analysis:

- Use the data to create tables like Table 2 and Table 3 above.

- Identify which methods perform best for specific environments (e.g., surfaces, interfaces).

Protocol 2: Assessing Energy Function Components with In Silico Mutagenesis

Objective: To probe the limitations of an energy function by measuring its ability to predict the stability changes caused by point mutations (ΔΔG).

Materials:

- Software: A method with a customizable energy function, such as FoldX [3] or Rosetta.

- Dataset: A set of proteins with experimentally measured ΔΔG values upon mutation (e.g., from thermal denaturation studies).

Procedure:

- Structure Preparation:

- Use the wild-type crystal structure. Repair any structural defects (e.g., missing atoms, bad rotamers) using the software's repair function.

Generate Mutants:

- For each mutant in the benchmark set, use the software's mutagenesis function to introduce the mutation and repack the side-chains.

Energy Calculation:

- Calculate the folded state energy for both the wild-type and mutant structures.

- The software will often compute and output the predicted ΔΔG directly.

Validation:

- Plot predicted ΔΔG vs. experimental ΔΔG.

- Calculate the correlation coefficient (Pearson's r) and the root-mean-square error (RMSE). A low correlation or high RMSE highlights inaccuracies in the energy function, such as poor modeling of solvation or electrostatic effects.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item Name | Function/Application | Specifications & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| SCWRL4 [3] | Side-chain prediction for homology modeling and protein design. | Uses graph decomposition and DEE; fast and accurate for core residues. |

| Rosetta-fixbb [3] | High-resolution structure refinement and design. | Uses Monte Carlo sampling with a detailed physical- and knowledge-based energy function. |

| FoldX [3] | Protein engineering & stability prediction (ΔΔG). | Its RepairPDB function is useful for preparing structures for benchmarking. |

| Colony Energy [19] | Improve prediction of surface and flexible residues. | A computational term to approximate side-chain entropy; can be implemented in custom protocols. |

| Dunbrack Rotamer Library [3] | Provides discrete side-chain conformations for prediction. | A backbone-dependent rotamer library used by many methods (e.g., SCWRL4, Rosetta). |

| PDB Structures | Source of "native" conformations for benchmarking. | Use high-resolution (<1.8 Å) structures with clear electron density for reliable ground truth [13]. |

| AlphaFold2/ColabFold [15] [2] | State-of-the-art backbone and side-chain prediction. | Useful for generating starting models; but assess side-chain confidence (pLDDT) critically, as χ accuracy can be low [15]. |

Relationship Between Packing Density, Solvent Accessibility, and Predictability

The accurate prediction of protein side-chain conformations is a critical determinant of success in computational structural biology, impacting applications ranging from protein design to drug development. The predictability of a side-chain's conformation is not uniform across a protein structure but is heavily influenced by its local structural environment. This application note examines the central relationship between two key structural properties—local packing density and solvent accessibility—and their combined influence on the predictability of side-chain conformations. Framed within a broader thesis on protein side-chain conformation prediction methods, this document provides a detailed analysis of this relationship, supported by quantitative data, experimental protocols, and practical guidelines for researchers. Evidence consistently demonstrates that while both factors are important, local packing density, often quantified by metrics such as Weighted Contact Number (WCN), is the dominant structural determinant of side-chain conformational variability and prediction accuracy [21] [22].

The correlation between structural features and predictability has been quantified through various studies. The table below summarizes key findings on how packing density and solvent accessibility influence side-chain conformational predictability.

Table 1: Influence of Packing Density and Solvent Accessibility on Side-Chain Predictability

| Structural Feature | Quantitative Measure | Impact on Predictability | Key Evidence |

|---|---|---|---|

| Local Packing Density (Core Regions) | High Weighted Contact Number (WCN) / Contact Number (CN) | >90% prediction accuracy for core residues in soluble proteins, protein-protein interfaces, and transmembrane proteins [23]. | Core residues are densely packed, restricting side-chains to a limited set of stable rotamers [23]. |

| Solvent Accessibility (Non-Core Regions) | Relative Solvent Accessibility (rSASA) | High predictability (~80% within 30°) is maintained up to rSASA ≈ 0.3 [23]. | Predictability decreases as solvent accessibility increases, but a threshold exists where packing still dominates [23]. |

| Comparative Influence | Correlation with evolutionary rate (a proxy for constraint/predictability) | Local packing density (WCN/CN) is a ~4x stronger determinant of sequence variability than solvent accessibility (RSA) [21]. | Packing density provides a superior explanation for site-specific evolutionary constraints compared to solvent accessibility [21]. |

| Protein-Protein Interfaces | Normalized WCN (zWCN) of unbound subunit interfaces | Central interface residues are more rigid (higher WCN) than non-interface residues; peripheral interface residues are more flexible (lower WCN) [22]. | Interfaces have a distinct dynamic pattern that influences side-chain conformations even before binding [22]. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Quantifying Packing Density and Solvent Accessibility

This protocol details the calculation of Weighted Contact Number (WCN) and Relative Solvent Accessibility (rSASA), two fundamental metrics for characterizing a residue's local environment.

- Objective: To compute standardized measures of local packing density and solvent accessibility for each residue in a protein structure.

- Input: A protein structure file in PDB format.

Software Requirements:

Methodology:

- Calculate Weighted Contact Number (WCN):

- For a given residue

i, the WCN is calculated using the formula:w_i = Σ_{j≠i} (1 / r_ij^2)wherer_ijis the distance between the Cα atoms of residueiand residuej[21] [22]. - Summation is typically performed over all other residues

jin the same protein chain. - The resulting WCN value is a residue-specific measure of its local packing density, with higher values indicating a more densely packed environment [22].

- For a given residue

- Calculate Solvent Accessibility:

- Compute the Absolute Solvent Accessibility (ASA) for each residue by rolling a probe of 1.4 Å (representing a water molecule) over the residue's molecular surface [21].

- Calculate the Relative Solvent Accessibility (rSASA) by normalizing the ASA by the maximum solvent accessibility for that specific amino acid type found in an extended Gly-X-Gly tripeptide conformation [22].

rSASA = ASA / ASA_max

- Data Normalization (for cross-protein comparison):

- To compare WCN across proteins of different sizes, normalize the WCN values to z-scores for all surface residues within a single subunit:

z = (w - μ_w) / σ_w, whereμ_wandσ_ware the mean and standard deviation of WCN for that subunit [22].

- To compare WCN across proteins of different sizes, normalize the WCN values to z-scores for all surface residues within a single subunit:

- Calculate Weighted Contact Number (WCN):

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Side-Chain Prediction Accuracy

This protocol outlines a standard procedure for evaluating the performance of side-chain packing (PSCP) methods on experimental and predicted protein structures.

- Objective: To assess the accuracy of a PSCP method in predicting side-chain conformations given a fixed backbone structure.

- Input:

- A set of high-resolution protein crystal structures (e.g., from CASP datasets).

- AlphaFold2/3-predicted structures for the corresponding sequences [10].

Software Requirements:

Methodology:

- Data Preparation:

- Obtain a benchmarking dataset, such as single-chain targets from CASP14 or CASP15, with lengths under 2,000 residues [10].

- For each target, gather the experimental (native) structure and the corresponding AlphaFold-predicted structure.

- Run Side-Chain Packing:

- Using the native backbone as input, run the PSCP method to repack all side-chains. This establishes a baseline performance on ideal inputs.

- Using the AlphaFold-predicted backbone as input, run the same PSCP method to repack the side-chains. This tests the method's robustness to inaccuracies in predicted backbones [10].

- Accuracy Assessment:

- For each residue, calculate the deviation between the predicted dihedral angles (χ₁, χ₂, etc.) and the angles in the experimental reference structure.

- A prediction is typically considered correct if all χ angles are within 40° of the experimental values [15].

- Calculate the overall accuracy for the entire protein, as well as stratified by residue type, secondary structure, and SASA/rSASA bins (e.g., core: rSASA < 0.1, boundary: 0.1 ≤ rSASA < 0.3, surface: rSASA ≥ 0.3) [23].

- Analysis:

- Compare the accuracy of side-chain predictions on native vs. AlphaFold-predicted backbones.

- Correlate prediction accuracy with the local packing density (WCN) and solvent accessibility (rSASA) of residues to identify environments where prediction fails or succeeds.

- Data Preparation:

Diagram 1: Workflow for Side-Chain Predictability Analysis. This diagram outlines the logical sequence for analyzing how packing density and solvent accessibility influence side-chain prediction accuracy.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

The following table lists essential computational tools and resources for conducting research on protein side-chain conformations.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Side-Chain Conformation Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| SCWRL4 [10] | Software Algorithm | Widely-used rotamer library-based method for Protein Side-Chain Packing (PSCP). |

| Rosetta/PyRosetta [10] | Software Suite | Provides the "Packer" function for PSCP using rotamer libraries and energy minimization; used for structural refinement and design. |

| AlphaFold2/3 [15] [10] [6] | Deep Learning Model | Provides highly accurate protein structure predictions, including side-chain coordinates, which serve as a baseline or input for further packing. |

| AttnPacker & DiffPack [10] | Deep Learning Model | State-of-the-art, end-to-end deep learning methods for direct side-chain coordinate prediction. |

| DSSP [22] | Software Algorithm | Standard tool for assigning secondary structure and calculating solvent accessibility from 3D structures. |

| CATH [24] | Database | Provides protein domain classification, used for creating non-redundant benchmarking datasets. |

| Binding Interface Database (BID) [24] | Database | Source of protein-protein interface data for training and testing predictive models of interaction hot spots. |

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) [24] | Database | Primary repository for experimentally-determined 3D structures of proteins and nucleic acids, serving as the source of "ground truth" data. |

Advanced Considerations and Future Directions

The Challenge of Predicting Alternative Conformations

Proteins are dynamic and can adopt multiple conformations. Predicting these alternative states remains a significant challenge. While traditional PSCP methods assume a single, fixed backbone, new approaches are emerging. For example, the Cfold network, trained on a conformational split of the PDB, uses techniques like MSA clustering and dropout during inference to sample alternative side-chain arrangements and backbone shifts from a single input sequence [6]. Conformational changes can be categorized into hinge motions, domain rearrangements, and rare fold switches, each presenting different challenges for side-chain packing algorithms [6].

AlphaFold's Role and Limitations in Side-Chain Prediction

AlphaFold has revolutionized structure prediction, but its side-chain predictions require careful evaluation. Studies show that while AlphaFold's overall structure accuracy is high, its side-chain dihedral angle predictions can have significant errors, particularly for χ₂ and χ₃ angles, with accuracy decreasing as the rotamer index increases [15]. Furthermore, when AlphaFold-predicted backbones are used as input for specialized PSCP methods, the resulting side-chain repacking often does not yield consistent or pronounced improvements over AlphaFold's own initial side-chain predictions [10]. This suggests that the current PSCP methods are highly optimized for experimental backbones and may not fully generalize to the subtle inaccuracies present in predicted backbones. For protein complexes, while AlphaFold3 shows high overall accuracy, it can exhibit major inconsistencies in interfacial contacts and apolar-apolar packing, which are critical for understanding binding affinity and hot spots [25].

Diagram 2: Advanced Multi-Conformation Prediction Workflow. This diagram illustrates a strategy for predicting alternative protein conformations, which can involve different side-chain packing states, using methods like MSA clustering with structure prediction networks.

Methodological Approaches and Practical Applications in Biomedicine