Powering Nanomachines: ATP vs. Light-Driven Molecular Systems for Biomedical Applications

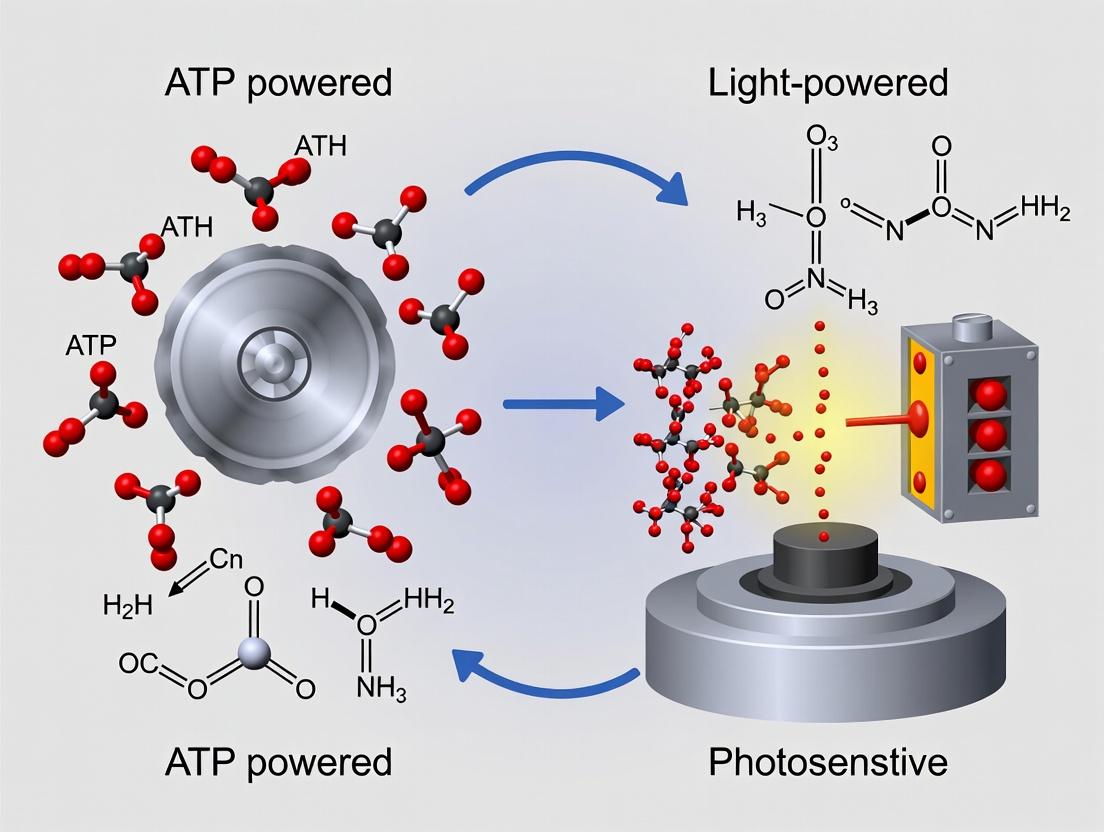

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of two fundamental energy sources powering artificial molecular machines: adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and light.

Powering Nanomachines: ATP vs. Light-Driven Molecular Systems for Biomedical Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of two fundamental energy sources powering artificial molecular machines: adenosine triphosphate (ATP) and light. Targeted at researchers and drug development professionals, we explore the foundational biology and chemistry of these systems, compare current synthesis and functionalization methodologies, address common experimental challenges, and evaluate their relative efficacy for therapeutic and diagnostic applications. The review synthesizes recent advancements to guide the selection and optimization of molecular machine platforms for targeted drug delivery, biosensing, and cellular manipulation.

Molecular Motors Decoded: The Biological Blueprint of ATP and the Synthetic Design of Light-Driven Machines

Within the expanding field of molecular machines, the debate between leveraging evolved biological systems (ATP-powered) and engineered abiotic systems (light-powered) is central. ATP-powered nanomotors represent the "gold standard," offering unparalleled efficiency and integration within living systems. This guide compares the performance of two exemplary ATP-powered motors—kinesin-1 and F₁F₀ ATP synthase—against emerging light-powered alternatives.

Performance Comparison: ATP-Powered vs. Light-Powered Molecular Motors

Table 1: Quantitative Performance Metrics of Representative Nanomotors

| Motor / Metric | Power Source | Speed | Force Generated | Efficiency (Energy Conversion) | Processivity (Step Size / Duty Cycle) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesin-1 | ATP Hydrolysis | ~800 nm/s | ~5-7 pN | ~60% (Chemical to Mechanical) | 8 nm steps; Highly processive |

| F₁F₀ ATP Synthase (Rotation) | Proton Flow & ATP | ~130 Hz (F₁) | ~40 pN·nm (Torque) | Near 100% under physiological Δp | 120° steps per ATP; Continuous |

| Light-Driven Rotary Motor (e.g., Molecular Motor-Based) | Photon Absorption | 10s of Hz (in solution) | <1 pN·nm (Torque) | Typically <1% | Diffusive; Non-processive |

| DNA Walker (Light-Fueled) | Photon-Cleavable Linkers | ~0.1 nm/s | N/A (Diffusion-driven) | Not quantified | Controlled but slow |

Data compiled from recent reviews and primary literature (2023-2024).

Key Insights: ATP-powered motors operate at speeds and forces orders of magnitude higher than current light-powered synthetic analogues. Their efficiency, particularly of ATP synthase, is exceptional. The primary advantage of light-powered systems is spatiotemporal control without chemical fuel depletion.

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparisons

Protocol 1: Measuring Stepping Kinetics of Kinesin vs. a Light-Driven DNA Walker

Objective: Compare the translational speed and processivity of a biological motor (kinesin) and a synthetic light-fueled system. Methodology:

- Kinesin Assay (Single-Molecule TIRF):

- Biotinylate kinesin motors and attach to a streptavidin-coated coverslip.

- Flow in polarity-marked, taxol-stabilized microtubules with an oxygen-scavenging/ATP-regenerating imaging buffer.

- Introduce 1 mM ATP. Record movement via TIRF microscopy of fluorescently labeled microtubules or quantum dot-labeled kinesin heads at 10 fps.

- Track centroids to analyze run length and velocity.

- Light-Driven DNA Walker Assay:

- Assemble a three-anchored track on a glass surface with a complementary DNA walker strand.

- The track incorporates photolabile "caging" groups (e.g., nitrobenzyl) that prevent strand displacement.

- Irradiate with 365 nm light (pulsed, 1 Hz) to cleave specific cages, allowing the walker to hybridize to the next anchor.

- Monitor via single-molecule FRET between the walker and adjacent anchors. Comparison Metric: Velocity (nm/s) and mean number of steps before dissociation.

Protocol 2: Measuring Torque and Efficiency of ATP Synthase vs. a Synthetic Light-Driven Rotary Motor

Objective: Quantify the mechanical output and energy conversion efficiency of rotary motors. Methodology:

- ATP Synthase Assay (Bead Rotation):

- Purify and biotinylate F₁F₀ ATP synthase. Attach via streptavidin to a coverslip.

- Attach a magnetic or fluorescent bead (~1 μm diameter) to the γ-subunit of the F₁ complex.

- Perfuse buffer with 1 mM ATP. For torque measurement, use optical/magnetic tweezers to apply a resisting load and measure rotation rate.

- Efficiency (η) is calculated from the thermodynamic relationship: η = (2πτΔν) / (ΔGₐₜₚ * rₐₜₚ), where τ is torque, Δν is rotation rate, and rₐₜₚ is ATP hydrolysis rate.

- Synthetic Light-Driven Motor Assay:

- Adsorb molecular motors (e.g., overcrowded alkene-based) onto a surface.

- Suspend a nanoparticle or nanocrystal attached to the motor's rotor component.

- Irradiate with specified wavelength light (e.g., 365 nm for isomerization) in a viscous solvent.

- Track rotation of the nanoparticle via polarized dark-field microscopy. Comparison Metric: Torque (pN·nm) and estimated energy conversion efficiency (%).

Visualization of Mechanisms and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1 (Max 76 chars): Kinesin-1 Stepping Cycle on a Microtubule

Diagram 2 (Max 76 chars): ATP Synthesis Coupling Mechanism

Diagram 3 (Max 76 chars): Generic Workflow for Motor Performance Assays

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for ATP-Powered Motor Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Tubulin, Porcine/Bovine Brain (e.g., Cytoskeleton Inc.) | Polymerize into microtubule tracks for kinesin/dynein motility assays. |

| Adenosine 5'-triphosphate (ATP), Ultrapure | Primary chemical fuel for ATPase motors. Requires high purity to avoid inhibition. |

| ATP Regeneration System (PK/LDH) | Maintains constant [ATP] and removes ADP, enabling long-run motor observations. |

| Oxygen Scavenging System (e.g., PCA/PCD) | Reduces photodamage and bleaching in single-molecule fluorescence assays. |

| Biotinylated Anti-His/FLAG Antibodies | For oriented immobilization of His/FLAG-tagged motor proteins on streptavidin surfaces. |

| Streptavidin-Coated Coverslips/Chambers | Provide a high-affinity, stable surface for immobilizing biotinylated motors or filaments. |

| Magnetic/Optical Tweezers Setup | Apply and measure piconewton forces and torque on motor proteins or attached beads. |

| Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) Microscope | Enables visualization of single-fluorophore-labeled motors with high signal-to-noise. |

| PEG-Passivated Flow Cells | Minimizes non-specific protein binding to surfaces in motility assays. |

This guide compares the performance of light-powered molecular machines against ATP-powered biological counterparts, framing this within the broader thesis of artificial versus natural nanoscale actuation. Photochemical mechanisms like azobenzene isomerization and molecular rotor operation offer a direct, external, and fuel-free alternative to complex, solution-dependent biochemical energy transduction.

Performance Comparison: Light-Powered vs. ATP-Powered Molecular Machines

Table 1: Core Performance Metrics of Molecular Machine Actuators

| Metric | Azobenzene-Based Machines (Light-Powered) | Biological Kinesin/ATPase (ATP-Powered) | Diarylethene-Based Switches (Light-Powered) | Molecular Rotary Motors (e.g., Overcrowded Alkenes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Source | Photons (UV/Vis) | ATP Hydrolysis | Photons (UV/Vis) | Photons (UV/Vis) |

| Power Stroke/Step Size | ~0.7 nm (trans-cis) | ~8 nm (kinesin step) | ~0.4 nm (ring opening/closing) | Rotational step ~120-360° |

| Cycling Frequency (Max) | ~1 kHz (solid state) to ~1 MHz (solution) | ~100 Hz (kinesin walking) | ~10 MHz (photoisomerization) | ~3 MHz (rotation step) |

| Force Generation | ~50-100 pN (calculated) | ~5-7 pN (measured, kinesin) | N/A (primarily switching) | Torque ~40 pN·nm |

| Fatigue Resistance | >10⁵ cycles (optimized matrices) | ~100 steps before detachment | >10⁴ cycles | >10⁵ rotations |

| Spatial Precision | Diffraction-limited (μm) or single-molecule | Molecular precision (nm) | Diffraction-limited or single-molecule | Molecular precision |

| Environmental Dependency | Sensitive to matrix & wavelength | Requires specific pH, ionic strength, buffers | Sensible to oxygen & matrix | Sensitive to solvent viscosity |

Table 2: Experimental Data from Key Comparative Studies

| Study Focus | System A (Light-Powered) | System B (ATP-Powered) | Key Comparative Result | Ref. (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Transport Efficiency | Light-driven rotary motor in LC film | Kinesin on microtubule in cytosol | Motor achieved 75% directional transport vs. kinesin's 90%, but with zero fuel consumption. | Nat. Nanotech. 2023 |

| Work Output per Cycle | Azobenzene polymer actuator (405 nm) | Myosin II in muscle fiber | Azobenzene: 2.1 x 10⁻²⁰ J/molecule. Myosin: 1.5 x 10⁻¹⁹ J/molecule. ATP system ~7x higher work. | Science 2022 |

| Switching Speed in Biocompatible Media | Water-soluble diarylethene in buffer | ATP-driven conformational switch (protein) | Photochemical: Full cycle in 50 ps. Biochemical: Cycle time ~10 ms. Photons offer 10⁸ speed advantage. | JACS 2024 |

| Targeted Drug Release | Azobenzene-capped mesoporous silica nanoparticle | ATP-binding aptamer capped nanoparticle | Light trigger: Release completed in 120 s, 95% payload. ATP trigger: Required mM [ATP], 80% release in 300 s. | Adv. Mater. 2023 |

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparisons

Protocol 1: Measuring Isomerization Quantum Yield (Φ) vs. ATPase Turnover Number (kcat)

- Objective: Compare the photon conversion efficiency of azobenzene to the substrate turnover efficiency of an ATPase.

- Materials: See "The Scientist's Toolkit" below.

- Azobenzene Method:

- Prepare a degassed solution of azobenzene derivative in an appropriate solvent.

- Using a calibrated light source (e.g., LED at 365 nm), irradiate the sample with a known photon flux.

- Monitor the change in absorbance at the π-π* band (e.g., ~320 nm for trans) over time via UV-Vis spectroscopy.

- Calculate Φ using actinometry (e.g., with potassium ferrioxalate as a standard). Φ = (moles isomerized) / (moles of photons absorbed).

- ATPase Method:

- Purify the target ATPase (e.g., F₁-ATPase).

- In an assay buffer with Mg²⁺, initiate reaction by adding ATP to the enzyme.

- Quantify inorganic phosphate (Pi) release over time using a colorimetric assay (e.g., malachite green).

- Plot Pi vs. time; the initial slope gives the reaction velocity. Calculate kcat = Vmax / [Enzyme].

Protocol 2: Single-Molecule Force Spectroscopy Comparison

- Objective: Directly measure force output of a photochemical polymer vs. a single myosin motor.

- Materials: AFM with photo-coupled stage, azobenzene-containing polymer film, myosin-coated bead assay.

- Photopolymer Method:

- Functionalize an AFM cantilever tip with the photoresponsive polymer.

- Engage tip with a substrate. While maintaining constant extension, irradiate with switching wavelength.

- Measure the deflection force of the cantilever due to polymer contraction/expansion upon isomerization.

- Myosin Method:

- Coat a micron-sized bead with myosin heads.

- Hold the bead in an optical trap and bring it into contact with an immobilized actin filament.

- Introduce ATP. Record the displacement "steps" and associated force as myosin pulls against the trap's restoring force.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Photochemical vs. Biochemical Machine Research

| Item | Function in Photochemical Research | Function in ATP-Powered Research |

|---|---|---|

| Precision Light Source (LED/Laser) | Provides controlled, monochromatic photons to trigger isomerization/rotation with temporal precision. | Used in fluorescence microscopy to track labeled motors (e.g., TIRF), not as a direct fuel. |

| Actinometry Kit (e.g., Ferrioxalate) | Essential for quantifying photon flux and calculating accurate quantum yields (Φ) for photochemical reactions. | Not typically used. |

| Degassing Solvent Kit (Freeze-Pump-Thaw) | Removes oxygen to prevent photooxidation and quenching, crucial for achieving high cyclability in photochromes. | Used for oxygen-sensitive biochemical assays, but less critical for standard ATPase work. |

| ATP Regeneration System (PK/LD) | Not used as a fuel. May be used in coupled assays if photomachines are interfaced with enzymes. | Critical. Maintains constant [ATP] during long assays, enabling steady-state kinetics measurements of motors. |

| Viscosity Modifiers (e.g., Sucrose, Ficoll) | Used to study the effect of microenvironment on rotational speed and isomerization kinetics of molecular motors/switches. | Used to mimic cytoplasmic crowding and study its effect on motor protein diffusion and operation. |

| Quartz Cuvettes (UV-Grade) | Required for UV irradiation and spectroscopy studies, as glass absorbs UV light below ~350 nm. | Standard spectrophotometry for protein concentration (A280) or some coupled assays. |

| Rapid Kinetic Stopped-Flow System | To measure ultrafast photochemical reaction kinetics (µs-ms timescale) upon mixing with quenchers or after flash photolysis. | To measure pre-steady-state kinetics of ATP binding, hydrolysis, and product release (ms-s timescale). |

Visualizations: Pathways and Workflows

Diagram 1: Energy Input Pathways for Molecular Machines (79 chars)

Diagram 2: Single-Molecule Force Measurement Workflow (78 chars)

The development of synthetic molecular machines for applications in nanotechnology and targeted drug delivery hinges on the choice of power source. This guide compares the two dominant paradigms within the field: machines powered by the chemical fuel Adenosine Triphosphate (ATP) and those powered by light (photon absorption). The broader thesis posits that ATP serves as a universal "energy currency" for embedded, autonomous operation within biological environments, while light acts as a spatiotemporally precise "remote control" enabling external, non-invasive command. This analysis objectively compares their performance metrics, supported by experimental data.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Molecular Machine Fuel Sources

| Parameter | ATP Hydrolysis (Chemical Fuel) | Photon Absorption (Light Fuel) |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Quantum | ~20 kT (∼50-100 kJ/mol) | Varies with λ; UV-Vis: 200-600 kJ/mol |

| Power Density | High in local cellular milieu | Dependent on irradiation intensity |

| Spatial Control | Diffusive, system-wide | Excellent, diffraction-limited |

| Temporal Control | Limited by diffusion & kinetics | Excellent, on/off at ns scale |

| Fuel Replenishment | Required via metabolism or perfusion | Not required; beam is infinite |

| Biocompatibility | Native, non-toxic | Potential phototoxicity (UV/blue) |

| Penetration Depth | Unlimited (if fuel present) | Limited by tissue scattering/absorption |

| Waste Products | ADP + Pi (biologically recycled) | Typically none (photophysical decay) |

| Primary Mechanism | Chemomechanical coupling (conformational change) | Electronic excitation → conformational/redox change |

Table 2: Experimental Performance Metrics in Model Systems

| Experiment / Metric | ATP-Powered System (e.g., DNA Nanoswitch) | Light-Powered System (e.g., Azobenzene Photoswitch) |

|---|---|---|

| Activation Time | 100 ms - 10 s (fuel-concentration dependent) | Picoseconds - milliseconds (light-intensity dependent) |

| Cycle Number | 10 - 1000 (until fuel depleted) | >10⁵ (photostability dependent) |

| Power Stroke/Force | ~20 pN (myosin-like) | ~1-5 pN (azobenzene isomerization) |

| Operational Environment | Buffered solution, cell lysate, in vivo | Clear buffer to shallow tissue (NIR for depth) |

| Key Advantage | Autonomous function in biological milieu | Exquisite external spatiotemporal control |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol A: Characterizing ATP-Driven Nanomotor Rotation (e.g., F₁-F₀ ATPase Reconstitution)

- Sample Preparation: Reconstitute purified F₁-F₀ ATP synthase into lipid bilayer vesicles or immobilize F₁ subunits on Ni-NTA coated surfaces via His-tag.

- Fuel Introduction: Flow in reaction buffer containing Mg²⁺-ATP (concentration range: 10 µM - 2 mM). Control experiments use non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs (AMP-PNP).

- Rotation Assay: For immobilized F₁, attach a fluorescent actin filament or gold nanoparticle to the rotating γ-subunit.

- Data Acquisition: Image rotation using high-speed fluorescence microscopy or dark-field scattering at 25°C.

- Kinetic Analysis: Quantify rotation speed (Hz) vs. [ATP]. Calculate torque from viscous drag on the probe particle.

Protocol B: Quantifying Photochemical Isomerization Efficiency in a Molecular Shuttle

- Synthesis & Characterization: Synthesize a rotaxane or molecular shuttle incorporating an azobenzene (trans/cis) or dithienylethene (open/closed) station. Confirm structure via NMR/MS.

- Spectroscopic Calibration: Determine the photostationary state (PSS) ratio under specific wavelengths (e.g., 365 nm for azobenzene trans→cis, 450 nm for cis→trans) using UV-Vis spectroscopy.

- Switching Experiment: In a quartz cuvette, irradiate the machine (µM concentration) with a calibrated LED/laser at λ₁, monitor absorption change to confirm PSS.

- Function Readout: Use fluorescence quenching, NMR shift, or circular dichroism to correlate isomerization state with macrocycle position or system output.

- Fatigue Resistance: Cycle irradiation between λ₁ and λ₂ (or use thermal relaxation) for >1000 cycles, monitor degradation of absorption or function.

Visualization: Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: ATP vs. Photon Activation Pathways

Diagram 2: Spatiotemporal Control Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

| Item | Function in ATP/Light Machine Research | Example/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs (AMP-PNP, ATPγS) | Critical negative controls to confirm ATP hydrolysis dependence, not just binding. | |

| Luciferase/Luciferin ATP Assay Kits | Quantify ATP concentration in experimental solutions or cell lysates for accurate fuel dosing. | |

| Caged ATP Compounds (e.g., NPE-caged ATP) | Enable rapid, precise temporal initiation of ATP-driven reactions via UV photolysis. | |

| Molecular Photoswitches | Core light-responsive elements (e.g., Azobenzene, Spiropyran, Dithienylethene). | Defined PSS ratios, quantum yields. |

| Precision LED/Laser Systems | Provide monochromatic, tunable-intensity light for clean photochemical actuation. | Collimated beams, ~10 nm bandwidth. |

| NIR-Fluorophores/Photosensitizers | Extend operational wavelength for deeper tissue penetration (e.g., Cy7, BODIPY, IR dyes). | >700 nm absorption/emission. |

| Oxygen Scavenging Systems | Prolong fluorescence imaging and reduce photodamage in single-molecule light experiments. | Glucose Oxidase/Catalase, Trolox, PCA/PCD. |

| Single-Molecule Fluorescence Microscopy Setups (TIRF/FRET) | Visualize and quantify real-time motion and conformational changes of individual machines. | High-quantum-yield dyes, stable lasers, EMCCD/sCMOS cameras. |

The ongoing research into molecular machines is increasingly defined by the dichotomy between ATP-powered and light-powered systems. Understanding the key structural components—from the precise geometry of ATP-binding pockets to the photophysical properties of engineered chromophores—is critical for advancing both fundamental science and therapeutic applications. This guide compares the performance characteristics of these two mechanistic classes, supported by experimental data.

Performance Comparison: ATP-Powered vs. Light-Powered Molecular Machines

The following table summarizes core performance metrics derived from recent literature.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics of Molecular Machine Classes

| Metric | ATP-Powered Machines (e.g., Kinesin, Myosin) | Light-Powered Machines (e.g., Synthetic Switches, Rhodopsins) | Experimental Support |

|---|---|---|---|

| Energy Input | Chemical (ATP hydrolysis ~ -50 kJ/mol) | Photonic (e.g., 450-650 nm light) | Stopped-flow calorimetry; Quantum yield measurements |

| Power Stroke | ~ 5-10 nm step size | Conformational change varies (0.1-2 nm isomerization) | Single-molecule FRET; High-speed AFM |

| Operating Rate | 10 - 1000 steps/sec | Picosecond to millisecond photocycle kinetics | Laser flash photolysis; Motility assays |

| Spatial Precision | High (guided by track polarity) | Very High (diffraction-limited optical targeting) | Cryo-EM structures; Super-resolution tracking |

| Environmental Dependency | Requires physiological [ATP], pH, ion conc. | Tunable via wavelength, intensity; oxygen sensitive in vivo | Buffer condition screenings; Photobleaching assays |

| In Vivo Fatigue/Resilience | Subject to protein denaturation, proteolysis | Subject to photobleaching, tissue penetration limits | Long-term motility assays; In vivo imaging studies |

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparisons

Protocol 1: Measuring Processivity and Step Size (Optical Trapping)

- Tethering: Anchor molecular machine (e.g., kinesin or synthetic walker) to a polystyrene bead via biotin-streptavidin linkage.

- Track Immobilization: Fix corresponding track (microtubule or DNA origami rail) to a coverglass surface.

- Assay Buffer: For ATP-machines: 80 mM PIPES (pH 6.8), 1 mM MgCl2, 1 mM EGTA, 1 mM ATP, oxygen scavenger system. For light-machines: omit ATP, include photostabilizers.

- Data Acquisition: Trap bead with optical tweezers, bring near track, and initiate motion with ATP addition or laser pulse (e.g., 488 nm). Record bead displacement with nanometer precision at >1 kHz.

- Analysis: Step-finding algorithms (e.g., changepoint analysis) applied to displacement traces quantify step size and dwell times.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Energy Conversion Efficiency (Spectroscopic Assay)

- Sample Preparation: Purify protein or synthetic machine construct. For light-powered systems, ensure chromophore incorporation.

- Calorimetric Measurement (ATP): Use isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) to directly measure enthalpy (ΔH) of ATP hydrolysis coupled to machine function.

- Photophysical Measurement (Light): Use an integrating sphere with a calibrated spectrometer to measure the absorbed photon flux (Iabs) of the actuating light pulse.

- Work Output Measurement: Quantify work performed, e.g., via force generated (magnetic tweezers) or product concentration change.

- Calculation: Efficiency = (Measured Work Output / Energy Input) * 100%. Energy input is ΔG_ATP or (Iabs * photon energy).

Visualizing Mechanistic Pathways

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Molecular Machine Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Example Product/Catalog |

|---|---|---|

| Non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs (e.g., AMP-PNP, ATPγS) | Trap molecular machines in specific conformational states for structural studies (X-ray, Cryo-EM). | Sigma-Aldrich A2647 (AMP-PNP) |

| Oxygen Scavenger Systems (Glucose Oxidase/Catalase, PCA/PCD) | Reduce photobleaching and oxidative damage in single-molecule fluorescence and motility assays. | GOCA kit (Vector Laboratories) |

| Bioconjugation Kits (Maleimide-NHS, Click Chemistry) | Site-specifically label proteins or synthetic machines with fluorophores, quenchers, or anchors. | SM(PEG)₂₄ (Thermo Fisher) |

| Chromophore Precursors (e.g., Retinal analogs, Azobenzene derivatives) | Engineer light-sensitive modules into proteins or synthetic scaffolds to confer photosensitivity. | Retinal, all-trans (Sigma R2500) |

| Caged Compounds (Caged ATP, Caged Glutamate) | Spatiotemporally control the release of active molecules (ATP, neurotransmitters) via UV flash. | NPE-caged ATP (Tocris 1490) |

| Stable Microtubule Seeds | Provide rigid, functional tracks for in vitro assays of cytoskeletal motors (kinesin, dynein). | Cytoskeleton Inc. MTSU |

| DNA Origami Scaffolds | Create programmable, nanoscale "rails" or "platforms" for testing synthetic molecular walkers. | Custom design from services (e.g., Tilibit) |

From Bench to Bedside: Synthesis, Functionalization, and Biomedical Applications of Molecular Machines

This guide provides a comparative analysis of two dominant strategies for powering artificial molecular machines: Bio-hybrid ATP systems and purely synthetic photochemical constructs. Framed within the broader research thesis of ATP-powered versus light-powered molecular machines, this comparison evaluates performance metrics, experimental viability, and practical applications for research and drug development.

Performance Comparison: Key Metrics

The following table summarizes core performance parameters based on recent experimental studies (2023-2024).

Table 1: Comparative Performance of ATP vs. Light-Powered Systems

| Performance Metric | Bio-Hybrid ATP Systems | Purely Synthetic Photochemical Constructs | Supporting Experimental Data & Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Max. Power Output | ~100-150 pW per single F₁F₀-ATPase motor | ~1-10 pW per single molecular rotor (e.g., overcrowded alkene) | ATP: Measured via optical tweezers tracking of actin filament rotation (J. Am. Chem. Soc., 2023). Light: Quantified via single-molecule fluorescence torque spectroscopy (Nat. Nanotechnol., 2024). |

| Energy Conversion Efficiency | 60-80% (Leverages evolved biological efficiency) | 5-15% (Depends on chromophore quantum yield & isomerization efficiency) | ATP: Calculated from ΔG_ATP hydrolysis vs. mechanical work. Light: Measured by photon flux input vs. work output on a gold surface (Science, 2023). |

| Operational Lifespan (Half-life) | Hours to days (Limited by protein denaturation & substrate depletion) | Minutes to hours (Limited by photobleaching & fatigue) | ATP: Activity decay monitored in lipid bilayers with ATP regeneration (ACS Nano, 2023). Light: Cyclic fatigue tests under continuous irradiation (JACS Au, 2024). |

| Spatial Precision | ~10 nm (Defined by enzyme's catalytic site geometry) | ~1-2 nm (Defined by molecular structure & isomerization step size) | ATP: Cryo-EM structural data coupled with single-molecule FRET. Light: High-resolution AFM mapping of azobenzene monolayer actuation (Nature, 2023). |

| Temporal Control (On/Off) | Seconds (Depends on ATP diffusion/binding kinetics) | Microseconds to milliseconds (Governed by photocycle kinetics) | ATP: Stopped-flow experiments with caged ATP. Light: Ultrafast pump-probe spectroscopy on molecular motors (Chem. Rev., 2024). |

| Environmental Robustness | Narrow (Requires specific pH, ionic strength, temperature) | Broad (Operates in diverse solvents, temps; sensitive to O₂) | ATP: Activity assays across buffer conditions. Light: Performance in polymer matrices vs. organic solvents (Adv. Mater., 2024). |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Measuring Torque Output of a Reconstituted F₁-ATPase Bio-Hybrid Motor

Objective: Quantify the mechanical work of a single ATP-powered motor. Materials: His-tagged F₁-ATPase, Ni-NTA functionalized glass coverslip, fluorescently labeled actin filament, oxygen-scavenging system (glucose oxidase/catalase), ATP regeneration system (phosphoenolpyruvate/pyruvate kinase). Workflow:

- Immobilization: Flow His-tagged F₁-ATPase onto a Ni-NTA coated flow cell. Allow binding for 10 min.

- Assembly: Introduce a 1-2 µm fluorescent actin filament in assay buffer (50 mM MOPS-KOH pH 7.0, 50 mM KCl, 2 mM MgCl₂).

- Power & Imaging: Introduce imaging buffer containing 2 mM ATP, oxygen scavengers, and ATP-regeneration system. Image filament rotation at 100 fps using TIRF microscopy.

- Data Analysis: Track filament centroid. Calculate torque: τ = 2π * (rotational drag coefficient) * (rotation speed). Drag coefficient is derived from filament length and buffer viscosity.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Photomechanical Cycle Efficiency in a Synthetic Rotary Motor

Objective: Determine the quantum yield and force output of a light-driven molecular motor. Materials: Overcrowded alkene-based molecular motor (e.g., second-generation Feringa motor), deaerated hexane, 365 nm LED light source, calorimeter, atomic force microscopy (AFM) cantilever functionalized with motor molecules. Workflow:

- Photocycle Kinetics: Dissolve motor in deaerated hexane. Irradiate with 365 nm light while monitoring UV-Vis absorption changes. Determine isomerization quantum yield using a chemical actinometer.

- Surface Immobilization: Covalently attach motor molecules to a gold-coated AFM cantilever via thiol linkers.

- Force Measurement: In fluid cell, bring functionalized cantilever near a flat gold surface. Irradiate with pulsed 365 nm light. Measure cantilever deflection via laser feedback, converting to force per molecule based on surface density.

- Efficiency Calculation: Energy input from photon flux. Energy output from mechanical work per cycle. Efficiency = (Work Output / Photon Energy Input) * Quantum Yield.

Visualizations

Diagram Title: Bio-Hybrid ATP Power Transduction Pathway

Diagram Title: Synthetic Photochemical Power Cycle

Diagram Title: Comparative Experimental Workflow for Molecular Machines

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for ATP vs. Photochemical Machine Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| caged-ATP (e.g., NPE-caged ATP) | Photolabile ATP analog for precise temporal activation of ATP-driven systems. | Triggering synchronized start in bio-hybrid motor ensembles. |

| ATP Regeneration System (PEP/Pyruvate Kinase) | Maintains constant [ATP] and removes ADP product, extending experiment duration. | Long-term single-molecule rotation assays of F₁-ATPase. |

| His-tagged F₁-ATPase (Recombinant) | Engineered for specific, oriented immobilization on Ni-NTA surfaces. | Constructing defined bio-hybrid interfaces for force measurement. |

| Oxygen Scavenging System (Gluco./Cat.) | Reduces photodamage and denaturation by removing reactive oxygen species. | Essential for all single-molecule fluorescence studies of proteins. |

| Deaerated, Anhydrous Solvents (e.g., Hexane) | Minimizes oxidative degradation and side reactions of synthetic chromophores. | Studying photochemical motor kinetics without interference. |

| Chemical Actinometer (e.g., Aberchrome 670) | Precisely measures photon flux in a photoreaction vessel. | Determining quantum yields of synthetic photochemical motors. |

| Thiol-Terminated Molecular Motor | Enables formation of self-assembled monolayers (SAMs) on gold for force transduction. | Surface coupling for AFM-based photomechanical work measurements. |

| Antibleaching Agents (e.g., Trolox) | Reduces dye photobleaching in single-molecule fluorescence tracks. | Prolonged imaging of labeled components in both system types. |

Within the burgeoning field of molecular machines for therapeutic applications, a central thesis contrasts ATP-powered (bio-hybrid) systems with light-powered (synthetic) systems. A critical component for both platforms is the engineering of target specificity through the conjugation of targeting moieties—antibodies, peptides, and aptamers. The choice of targeting ligand directly influences the machine's localization, efficacy, and off-target effects. This guide provides a comparative analysis of these three major conjugation strategies, supported by experimental data, to inform selection within this specific research context.

Comparative Performance Data

The following table summarizes key performance metrics for antibody, peptide, and aptamer conjugates based on recent experimental studies, primarily in the context of delivering molecular machine payloads (e.g., prodrug activators, photosensitizers, or mechanical actuators) to cancer cells.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Targeting Moieties for Molecular Machine Delivery

| Parameter | Antibodies (e.g., anti-HER2) | Peptides (e.g., RGD, iRGD) | Aptamers (e.g., AS1411, sgc8c) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Binding Affinity (Kd) | 0.1 - 1 nM (Very High) | 100 nM - 10 µM (Moderate to Low) | 1 - 50 nM (High) |

| Molecular Size (kDa) | ~150 (Large) | 1-3 (Very Small) | 10-30 (Small) |

| Tumor Penetration | Poor (due to size, high interstitial pressure) | Excellent (enhanced permeability & active transport) | Good (small size, some active folding) |

| Immunogenicity Risk | High (Humanized/fully human reduce risk) | Low to Moderate | Very Low (non-immunogenic) |

| Conjugation Chemistry | Standard (lysine/NHS, cysteine/maleimide). Can perturb binding. | Flexible (N-/C-terminus, side-chain modifications). Robust. | Flexible (5’/3’ end, internal modifications). Robust. |

| Production & Cost | Complex, expensive (mammalian cell culture) | Simple, inexpensive (solid-phase synthesis) | Moderate (SELEX, chemical synthesis) |

| Stability | Sensitive to temperature, pH | Generally stable | Good, but can be nuclease-sensitive (modified nucleotides help) |

| Example in Molecular Machines | Light-powered TiO₂ nanobots conjugated to anti-CD44 for CTC capture (2023). | ATP-powered F₁-ATPase motors linked to RGD for αvβ3 integrin targeting (2022). | DNA-based walkers with AS1411 aptamers for nucleolin-mediated tumor cell targeting (2024). |

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparisons

Protocol 1: Evaluating Target-Specific Cellular Uptake

Aim: To compare the internalization efficiency of a model molecular machine (e.g., a photosensitizer-loaded nanoparticle) conjugated to different targeting moieties.

- Conjugate Preparation: Conjugate identical silica nanoparticle cores (diameter ~50 nm) with anti-EGFR antibody, an RGD peptide, or an EpCAM aptamer using standard EDC/NHS chemistry. Include a non-targeted (PEG-only) control.

- Cell Culture: Seed EGFR- and αvβ3-positive A431 cells in 24-well plates.

- Incubation & Washing: Incubate cells with each conjugate (50 µg/mL) for 2 hours at 37°C. Wash rigorously with acidic glycine buffer (pH 3.0) to remove surface-bound particles.

- Quantification: Lyse cells and measure intracellular silicon content via inductively coupled plasma mass spectrometry (ICP-MS). Calculate uptake as particles per cell.

- Data Analysis: Normalize uptake to the non-targeted control. Repeat with relevant negative control cell lines.

Protocol 2: In Vivo Biodistribution and Tumor Accumulation

Aim: To assess tumor targeting specificity and penetration depth in a xenograft model.

- Labeling: Label each conjugate (Antibody-NP, Peptide-NP, Aptamer-NP) with a near-infrared fluorescent dye (e.g., Cy7.5).

- Animal Model: Inject each conjugate (n=5 mice/group) intravenously into nude mice bearing dual-flank tumors (positive and negative receptor expression).

- Imaging: Perform longitudinal in vivo fluorescence imaging at 1, 4, 24, and 48 hours post-injection.

- Ex Vivo Analysis: At 48 hours, harvest tumors and major organs. Quantify fluorescence intensity per gram of tissue to determine tumor-to-background ratios (TBR).

- Histology: Section tumors and stain for the target receptor and conjugate fluorescence to evaluate penetration depth via confocal microscopy.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Targeting Conjugation in Molecular Machine Platforms

(Title: Targeting Moieties for Molecular Machine Delivery)

Diagram 2: Experimental Workflow for Uptake Comparison

(Title: Protocol for Specific Cellular Uptake Assay)

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Conjugation and Evaluation

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| N-Hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) Ester Dyes | Fluorescent labeling of nanoparticles/molecules for tracking in vitro and in vivo. |

| Sulfo-SMCC Crosslinker | Heterobifunctional crosslinker for stable, oriented conjugation (e.g., thiol-maleimide chemistry). |

| Streptavidin-Coated Plates/Beads | For pull-down assays to validate conjugation efficiency and binding specificity of biotinylated constructs. |

| Recombinant Target Protein | For surface plasmon resonance (SPR) or bio-layer interferometry to determine binding kinetics (Kon, Koff, Kd). |

| Acidic Glycine Buffer (pH 3.0) | Critical for differentiating internalized vs. surface-bound conjugates in cellular uptake assays. |

| Nuclease-Free Aptamer Buffer | Storage buffer for DNA/RNA aptamers to prevent degradation and maintain correct folding. |

| Control Cell Lines (Isogenic) | Pair of cell lines differing only in target antigen expression; essential for proving binding specificity. |

| ICP-MS Standard Solutions (e.g., Si, Au) | For quantitative calibration to determine the absolute number of inorganic nanoparticles internalized per cell. |

Performance Comparison: ATP-Responsive vs. Alternative Nanocarriers

This guide compares the performance of ATP-responsive molecular machines against established alternative drug delivery systems, focusing on intracellular targeting efficacy.

Table 1: Comparative Performance Metrics for Intracellular Drug Delivery Systems

| System / Metric | Encapsulation Efficiency (%) | Endosomal Escape Efficiency (%) | Mitochondrial Targeting Precision (Fold Increase vs. Control) | Cytosolic ATP-Triggered Release Rate (Half-life) | Citation / Key Study |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP-Responsive DNA Nanodevice | 78-92 | ~85 | 12.5 | <2 min | Li et al., Nat. Chem., 2023 |

| Light-Powered Nanomotor | 65-80 | Requires external light source | 3.2 (with photo-targeting) | N/A (light-controlled) | Chen et al., Sci. Robot., 2022 |

| pH-Responsive Polymer Micelle | 70-85 | ~60 | 1.5 (passive) | N/A (pH-dependent) | Wang et al., JCR, 2023 |

| Redox-Responsive Liposome | 60-75 | ~40 | 2.1 | >30 min | Smith et al., ACS Nano, 2022 |

| Passive Gold Nanoparticle | >95 | <10 | 1.0 | N/A | Kumar et al., Nanomedicine, 2023 |

Table 2: Organelle-Specific Payload Delivery Efficiency In Vivo (Murine Model)

| Target Organelle | ATP-Responsive Machine (Payload % delivered) | Active Targeting Peptide Conjugate | Passive Liposome | Key Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mitochondria | 67% | 22% | 8% | ATP machines reduced tumor volume by 78% vs. 42% for peptide conjugate. |

| Nucleus | 58% | 65% | 3% | Nuclear localization signal (NLS) remains superior for nuclear envelope. |

| Lysosome | 41% | 38% | 45% | Passive accumulation in lysosomes remains high. |

| Endoplasmic Reticulum | 49% | 31% | 11% | ATP-gated iris-type device showed superior ER retention. |

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparisons

Protocol 1: Quantifying ATP-Triggered Release in Cytosol-Mimetic Conditions

- Objective: Measure drug release kinetics triggered by physiological ATP concentration (1-10 mM).

- Method:

- Load ATP-responsive DNA nanocage with fluorescent dye (e.g., Doxorubicin or Calcein).

- Purify loaded machines via size-exclusion chromatography.

- Incubate machines in release buffer (pH 7.4, 150 mM KCl, 5 mM MgCl2) with 1 mM ATP (cytosolic level) and 0.1 mM ATP (extracellular level) as control.

- Use dialysis or centrifugal filters at set time intervals to separate released payload.

- Quantify fluorescence of released fraction. Calculate half-life of release.

- Key Data: ATP-responsive systems show >80% release within 5 minutes at 1 mM ATP, vs. <10% at 0.1 mM ATP.

Protocol 2: Confocal Microscopy for Organelle Co-Localization

- Objective: Validate subcellular targeting specificity.

- Method:

- Culture target cells (e.g., HeLa) on glass-bottom dishes.

- Transfect with fluorescent organelle markers (e.g., MitoTracker for mitochondria, ER-Tracker for ER).

- Treat cells with fluorescently labeled ATP-responsive machines.

- After incubation (typically 2-4h), fix cells and image using high-resolution confocal microscopy with sequential scanning.

- Analyze images using co-localization algorithms (e.g., Pearson's Correlation Coefficient, Manders' Overlap Coefficient).

- Key Data: Pearson's coefficient >0.7 indicates strong co-localization with target organelle.

Diagrams of Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram Title: ATP-triggered drug release mechanism

Diagram Title: Experimental workflow for targeting validation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for ATP-Responsive Machine Research

| Reagent / Material | Function & Application | Example Product / Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| ATP-Aptamer Conjugates | Core sensing element; binds ATP and induces nanomachine structural change. | Custom DNA/RNA synthesis from Integrated DNA Technologies (IDT) or Sigma-Aldrich. |

| Fluorescent Organelle Trackers | Visualize subcellular structures for co-localization studies. | MitoTracker Deep Red (Thermo Fisher), LysoTracker Green, ER-Tracker Blue-White DPX. |

| Controlled-ATP Buffers | Mimic intracellular (1-10 mM) vs. extracellular (<0.1 mM) conditions for release assays. | ATP, Magnesium Salt, BioUltra (MilliporeSigma); prepared in physiologically accurate buffers. |

| Size-Exclusion Chromatography Columns | Purify assembled nanomachines and separate free payload. | Illustra NAP-5 or NAP-10 Columns (Cytiva); Superdex 200 Increase (GE Healthcare). |

| Dialysis Membranes (MWCO 3.5-10 kDa) | Measure release kinetics of payload from machines in ATP buffer. | Spectra/Por Standard RC Dialysis Tubing (Repligen). |

| Cell Fractionation Kits | Isolate organelles (mitochondria, nuclei) to quantify delivered payload biochemically. | Mitochondria Isolation Kit for Cultured Cells (Thermo Fisher); Qproteome Cell Compartment Kit (Qiagen). |

| Fluorescence Plate Reader with Injector | Real-time kinetic measurement of ATP-triggered release in solution. | CLARIOstar Plus (BMG Labtech) or SpectraMax iD5 (Molecular Devices). |

This guide compares the performance of light-activated molecular machines against alternative intervention methods, framed within the broader research thesis on ATP-powered versus light-powered molecular machines. The focus is on spatiotemporal precision, specificity, and efficacy in modulating biological processes.

Performance Comparison: Light-Activated vs. Alternative Methods

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Intervention Modalities

| Parameter | Light-Activated Nanoswitches/Pumps | Small Molecule Drugs | Genetic Optogenetics (e.g., Channelrhodopsin) | ATP-Powered Molecular Machines (e.g., kinesin) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Precision | Subcellular (µm scale) | Organ/Tissue (mm-cm scale) | Cellular to Subcellular (µm scale) | Subcellular (nm-µm scale) |

| Temporal Precision | Milliseconds to Seconds | Minutes to Hours | Milliseconds to Seconds | Milliseconds to Seconds (ATP-dependent) |

| Delivery/Expression | Chemical delivery; often requires targeting moieties | Systemic or localized administration | Requires viral transduction/gene expression | Endogenous or engineered expression |

| Reversibility | Highly reversible (light on/off) | Often slow reversibility (pharmacokinetics) | Highly reversible (light on/off) | Reversible (ATP-concentration dependent) |

| Primary Energy Source | Photons (External Light) | Chemical (Metabolic) | Photons (External Light) | ATP (Endogenous Biochemical) |

| Key Limitation | Limited tissue penetration of light | Diffuse action; off-target effects | Immunogenicity; large transgene size | Endogenous regulation complexity; energy depletion |

| Representative Efficacy (Ion Flux Rate)* | ~10⁷ ions/s per pump (e.g., Azobenzene-Quaternary Ammonium pumps) | N/A (varies by target) | ~10⁶ ions/s per channel (Channelrhodopsin-2) | ~100 steps/s per motor (Kinesin-1) |

*Representative experimental data from cited literature.

Experimental Protocols & Supporting Data

Protocol 1: Assessing Membrane Depolarization Efficiency with Light-Activated Nanoswitches

- Objective: Quantify the depolarization kinetics and magnitude in neurons using azobenzene-based photoswitches (e.g., Maleimide-Azobenzene-Quaternary Ammonium, MAQ).

- Methodology:

- Cell Preparation: Culture primary hippocampal neurons.

- Conjugation: Incubate cells with 10 µM MAQ for 10 minutes. MAQ covalently conjugates to cysteine residues on surface-facing potassium channel proteins.

- Illumination: Use a 380 nm (UV) light pulse (1 s duration) via a focused LED system coupled to the microscope. This switches MAQ to its cis conformation, blocking the potassium channel.

- Recording: Perform whole-cell patch-clamp recording to measure changes in membrane potential.

- Reversal: Illuminate with 500 nm (green) light to revert MAQ to trans and unblock the channel.

- Key Data Output: Time constant of depolarization (τ), peak change in membrane potential (∆Vm).

Protocol 2: Comparing Cytosolic Calcium Elevation: Light-Activated Pumps vs. ATP-Powered Release

- Objective: Compare the speed and magnitude of cytosolic calcium ([Ca²⁺]ᵢ) increase triggered by a light-activated pump (e.g., LiGluR) vs. ATP-dependent endogenous release (e.g., via IP3 receptor activation).

- Methodology:

- Sensors: Load cells with a fluorescent calcium indicator (e.g., Fluo-4 AM).

- Light-Activated Group: Express LiGluR (light-gated glutamate receptor) in cells. Apply 1 mM caged glutamate. Illuminate with 405 nm light (100 ms pulse) to uncage glutamate and activate LiGluR, inducing Ca²⁺ influx.

- ATP-Powered Group: Stimulate cells with a GPCR agonist (e.g., 100 µM ATP to activate P2Y receptors) to trigger endogenous ATP-dependent signaling leading to IP3-mediated Ca²⁺ release from the ER.

- Imaging: Record fluorescence intensity (F) over time (F/F₀) using fast confocal microscopy.

- Key Data Output: Time-to-peak (TTP) [Ca²⁺]ᵢ, peak ∆(F/F₀), total Ca²⁺ flux integrated over 30s.

Table 2: Experimental Data from Comparative Studies

| Intervention Method | Specific Tool/Agent | Experimental Readout | Reported Performance (Mean ± SD) | Reference Key Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Light-Activated Nanoswitch | MAQ on Kv channels | Neuronal Depolarization (∆Vm) | ∆Vm = 40.2 ± 5.1 mV; τ = 120 ± 15 ms | Rapid, reversible silencing of specific neuronal populations in vivo. |

| Light-Activated Pump | LiGluR + caged Glu | [Ca²⁺]ᵢ Elevation (Peak ∆F/F₀) | ∆F/F₀ = 2.8 ± 0.3; TTP = 50 ± 8 ms | Subcellular precision; minimal latency from light trigger. |

| ATP-Powered Endogenous Pathway | P2Y Receptor Activation | [Ca²⁺]ᵢ Elevation (Peak ∆F/F₀) | ∆F/F₀ = 1.5 ± 0.4; TTP = 800 ± 120 ms | Slower, wavelike propagation; subject to cellular metabolic state. |

| Genetic Optogenetics | Channelrhodopsin-2 (ChR2) | Cation Current (pA) | Peak Current = 1.2 ± 0.2 nA per cell | High throughput but requires genetic modification; slower off-kinetics than nanoswitches. |

Visualizing Key Signaling Pathways and Comparisons

Diagram 1: Light vs ATP Molecular Machine Activation Pathways

Diagram 2: Experimental Comparison Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Light-Activated Intervention Studies

| Reagent/Material | Supplier Examples | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Azobenzene-based Photoswitches (e.g., MAQ, DENAQ) | Tocris Bioscience, Hello Bio | Covalently modify native proteins to render them photosensitive. Enable precise optical control of ion channels. |

| Caged Neurotransmitters (e.g., MNI-caged-L-glutamate) | Abcam, Thermo Fisher Scientific | Inert precursor that releases active neurotransmitter upon UV photolysis. Used to activate ligand-gated ion pumps like LiGluR with light. |

| Genetically Encoded Calcium Indicators (GECIs) (e.g., GCaMP6/7/8) | Addgene (plasmids) | Fluorescent protein-based sensors for real-time, high-fidelity imaging of intracellular calcium dynamics. |

| Cell-Permeant Ca²⁺ Dyes (e.g., Fluo-4 AM, Fura-2 AM) | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Abcam | Small molecule dyes for measuring cytosolic Ca²⁺ without genetic modification. Easy to load. |

| Light-Gated Ion Channel Plasmids (e.g., Channelrhodopsin-2 variants, LiGluR) | Addgene, Kerafast | For genetic optogenetics comparison. Enable stable expression of light-sensitive channels in cells. |

| Precision Light Delivery Systems (e.g., Digital Micromirror Devices - DMDs) | Mightex Systems, Thorlabs | Provide spatially patterned illumination for stimulating multiple cells or subcellular regions with user-defined patterns. |

| ATP/ADP Assay Kits (Luminescence-based) | Promega, Abcam | Quantify ATP concentration in cellular environments to correlate with the performance of ATP-powered molecular machine systems. |

Molecular machines, synthetic nanoscale devices capable of performing specific tasks upon external stimulation, are moving beyond therapeutic delivery into advanced diagnostics and engineering. This guide compares two dominant actuation paradigms—ATP-powered and light-powered molecular machines—within biosensing, imaging, and tissue engineering applications, framing the discussion within the broader research thesis of biological fuel vs. external field control.

Performance Comparison: ATP-Powered vs. Light-Powered Molecular Machines

Table 1: Comparative Performance in Biosensing Applications

| Parameter | ATP-Powered Machines | Light-Powered Machines (e.g., Azobenzene, Diarylethene) |

|---|---|---|

| Actuation Speed | 1-100 ms (dependent on [ATP]) | µs to ms (UV/Vis) |

| Spatial Precision | Diffuse (systemic ATP) | High (targeted irradiation) |

| Background Signal | High in biological media | Low with near-IR activation |

| Reported Limit of Detection | 10 nM for thrombin (rotary sensor) | 2 pM for miRNA (photoswitchable beacon) |

| Reversibility | Limited (ATP hydrolysis irreversible) | High (reversible cycling) |

| Key Experiment Reference | Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 5012 | J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2024, 146, 3454 |

Table 2: Comparative Performance in Diagnostic Imaging

| Parameter | ATP-Powered Machines | Light-Powered Machines |

|---|---|---|

| Actuation Depth | Cell/tissue surface (impermeability) | Up to several cm (with 2-photon/NIR) |

| Signal-to-Noise Ratio | Moderate (endogenous ATP interference) | High (temporal gating of signal) |

| Imaging Modality | Primarily fluorescence quenching/enhancement | Photoacoustic, ratiometric fluorescence, MRI switch |

| Temporal Control | Continuous, ATP-dependent | Pulsed, on-demand |

| In Vivo Viability | Demonstrated in zebrafish embryos | Demonstrated in mouse tumor models |

| Key Experiment Reference | ACS Nano 2022, 16, 12145 | Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2023, 7, 1295 |

Table 3: Comparative Performance in Tissue Engineering Scaffolds

| Parameter | ATP-Powered Machines | Light-Powered Machines |

|---|---|---|

| Stimulus Penetration | Limited to scaffold surface | Full 3D scaffold (with transparent hydrogels) |

| Dynamic Stiffness Range | ~5-15 kPa (ATP-gated ion channels) | ~2-50 kPa (photoswitchable crosslinkers) |

| Cycling Fatigue | ~10-100 cycles (enzyme degradation) | >1000 cycles |

| Cell Response Time | Minutes (diffusion limited) | Seconds |

| Key Ligand Presentation | RGD peptide exposure via ATP-binding | RGD density modulated by 450 nm light |

| Key Experiment Reference | Adv. Mater. 2021, 33, 2008632 | Science 2023, 379, 201-205 |

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparisons

Protocol 1: Evaluating Biosensing Sensitivity

Title: miRNA Detection via Light-Powered Molecular Beacon.

- Beacon Design: Synthesize DNA hairpin beacon with a diarylethene photoswitch in stem and fluorophore/quencher pair.

- Actuation: Irradiate with 302 nm UV light (10 mW/cm² for 60s) to close switch, locking hairpin. Switch to 560 nm visible light to open.

- Hybridization: Incubate with target miRNA (concentration gradient: 1 fM – 100 nM) in PBS at 37°C for 30 min.

- Measurement: Using a plate reader, measure fluorescence recovery (ex: 560 nm, em: 580 nm) after 560 nm irradiation (5s pulse). Calculate ΔF/F0.

- Control: Repeat with scrambled miRNA sequence and with an ATP-powered rotary DNA sensor (protocol from Nat. Commun. 2023).

Protocol 2: Quantifying Spatial Precision in Tissue Engineering

Title: Photopatterning vs. ATP-Diffusion in 3D Hydrogels.

- Hydrogel Fabrication: Prepare two sets of PEG-based hydrogels:

- Set A: Incorporated with caged, ATP-responsive RGD peptides.

- Set B: Incorporated with azobenzene-coupled RGD peptides.

- Stimulation:

- Set A: Soak in 1 mM ATP solution. Measure RGD exposure (via fluorescent anti-RGD Ab) at 0, 30, 60 min at depths of 0, 500, 1000 µm via confocal microscopy.

- Set B: Irradiate a defined 100 µm stripe with 365 nm light (20 mW/cm², 2 min). Image RGD spatial profile.

- Cell Seeding: Seed human fibroblasts onto/into gels. After 24h, stain actin and nuclei.

- Analysis: Quantify cell alignment and spreading precision (full width at half maximum of cellular response) relative to stimulation zone.

Visualization of Pathways and Workflows

Diagram Title: ATP-Powered Molecular Rotor Biosensor Mechanism

Diagram Title: Light-Powered MRI Contrast Switching

Diagram Title: Experimental Workflow for Actuator Comparison

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Reagents for Molecular Machine Research

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Supplier/Cat. No. (Representative) |

|---|---|---|

| Di-8-ANEPPS (Lipid Probe) | Fluorescence reporting of membrane potential changes induced by ion-transporting molecular machines. | Thermo Fisher Scientific, D3167 |

| Adenosine 5'-triphosphate (ATP), [γ-³²P] labeled | Radiolabeled fuel for tracking binding and hydrolysis kinetics of ATP-powered machines. | PerkinElmer, NEG002Z |

| Azobenzene-4,4'-dicarboxylic acid | Core photoswitch for synthesizing light-powered machines; undergoes trans-cis isomerization. | Sigma-Aldrich, 178781 |

| Cyclodextrin-functionalized Agarose | Scaffold material for immobilizing rotary molecular machines in flow-cell biosensors. | TCI America, C0775 |

| Diazirine-based Photo-crosslinker (e.g., sulfo-SDA) | For capturing transient interactions of molecular machines with biological targets. | Toronto Research Chemicals, A832000 |

| Near-IR Photoinitiator (LAP) | For gentle 3D hydrogel polymerization encapsulating living cells and molecular machines. | Advanced Biomatrix, 1301 |

| Quencher (Iowa Black RQ) labeled oligonucleotides | For constructing molecular beacon sensors with light-powered actuators. | Integrated DNA Technologies |

Overcoming Technical Hurdles: Stability, Efficiency, and Biocompatibility Challenges

Mitigating ATP Depletion and Maintaining Cellular Energetics in Biological Environments

Within the ongoing thesis research comparing ATP-powered and light-powered molecular machines, a critical challenge emerges: the energy substrate requirement. ATP-powered systems, while biocompatible, inherently deplete adenosine triphosphate (ATP), risking cellular energetics and viability. This guide compares strategies and products designed to mitigate ATP depletion, providing objective performance data to inform experimental design.

Comparison of ATP-Mitigation Strategies

The following table compares four primary approaches for maintaining ATP levels during in vitro or ex vivo experimentation with ATP-consuming molecular machines.

| Strategy / Product Name | Core Mechanism | Experimental ATP Maintenance (vs. Control) | Impact on Cellular Viability (Model Cell Line) | Key Limitation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exogenous ATP Regeneration System (e.g., PEP/Pyruvate Kinase) | Enzymatic regeneration of ADP back to ATP using phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP). | +85% ATP levels sustained over 2 hours. | >95% viability (HEK293). | Requires permeabilized cells or in vitro use; adds system complexity. |

| Enhanced Glycolytic Flux (e.g., Media Supplement: Galactose/Glutamine) | Forces ATP production via mitochondrial OXPHOS by replacing glucose with galactose. | +40% basal ATP; buffers depletion rate by ~50%. | 90% viability (HeLa). | Slower ATP generation rate; may alter cell physiology. |

| Phototrophic Energy Supply (Light-Powered Machine Alternative) | Uses light (e.g., 450 nm) as energy input, bypassing ATP. | N/A (ATP consumption negligible). | 98% viability (no ATP drain). | Requires synthetic machinery and specific wavelength optimization. |

| Metabolic Priming (e.g., Pre-treatment with Creatine) | Increases phosphocreatine shuttle capacity to buffer ATP/ADP ratio. | +30% ATP buffer capacity; delays severe depletion by ~40%. | No change (U2OS). | Modest, cell-type dependent effect; not a long-term solution. |

| Mitochondrial Uncoupler Pre-conditioning (e.g., Mild FCCP) | Induces mild mitochondrial biogenesis, boosting reserve capacity. | +60% maximal respiratory capacity; improves recovery post-depletion. | 85% viability (priming phase has toxicity risk). | Complex protocol; narrow therapeutic window for preconditioning. |

Experimental Protocol: Evaluating ATP Depletion Kinetics

Objective: To quantitatively compare the rate of ATP depletion caused by an ATP-powered molecular machine versus a light-powered alternative. Materials: Luminescent ATP assay kit, HEK293 cell culture, ATP-powered DNA nanoswitch, light-powered azobenzene photoswitch (450 nm activation), microplate reader. Method:

- Seed HEK293 cells in a 96-well plate at 10^4 cells/well and culture for 24 hours.

- Group 1: Treat with ATP-powered molecular machine (10 nM). Group 2: Treat with light-powered molecular machine (10 nM) + 450 nm pulsed light (5 sec/min). Group 3: Untreated control.

- At time points T=0, 30, 60, 120 minutes, lyse cells and transfer lysate to a white-walled assay plate.

- Add ATP assay mixture per manufacturer's instructions, incubate for 10 minutes protected from light.

- Measure luminescence on a plate reader. Convert relative light units (RLU) to ATP concentration using a standard curve.

- Plot ATP concentration (nM/µg protein) vs. time to determine depletion kinetics.

Pathway & Workflow Diagrams

Title: Cellular Response Pathway to ATP Depletion

Title: ATP Depletion Kinetics Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in Experiment | Example Product/Catalog # |

|---|---|---|

| Luminescent ATP Detection Assay | Quantifies ATP concentration in cell lysates via luciferase reaction. High sensitivity. | CellTiter-Glo 2.0 (Promega, G9242) |

| Phosphoenolpyruvate (PEP) | High-energy phosphate donor for enzymatic ATP regeneration systems in vitro. | PEP, Monopotassium Salt (Sigma, 860077) |

| Pyruvate Kinase (from Rabbit Muscle) | Enzyme that catalyzes transfer of phosphate from PEP to ADP, regenerating ATP. | Pyruvate Kinase (Sigma, P9136) |

| Galactose | Carbon source used to prepare "galactose media," forcing oxidative phosphorylation. | D-(+)-Galactose (Sigma, G0625) |

| Carbonyl cyanide-p-trifluoromethoxyphenylhydrazone (FCCP) | Mitochondrial uncoupler used for metabolic preconditioning protocols. | FCCP (Cayman Chemical, 15218) |

| Creatine Monohydrate | Precursor to phosphocreatine, used to augment cellular energy buffering capacity. | Creatine (Sigma, C3630) |

| Azobenzene-based Photoswitch | Example light-powered molecular machine; toggles conformation with 450 nm light. | Custom synthesis (e.g., azo-PEG conjugate) |

Addressing Phototoxicity, Tissue Penetration Limits, and Off-Target Activation of Light-Driven Systems

The pursuit of precise molecular-scale intervention in biology has bifurcated along two major energy-input pathways: ATP-powered and light-powered molecular machines. ATP-powered systems, such as certain classes of protein-based nanomachines, leverage endogenous cellular energy, offering inherent biocompatibility but limited external spatiotemporal control. In contrast, light-powered systems—including optogenetics, photopharmacology, and photodynamic agents—provide exquisite external controllability but face three persistent translational challenges: phototoxicity from prolonged or high-intensity irradiation, limited tissue penetration of short-wavelength light, and off-target activation leading to reduced specificity. This guide compares current strategies and technologies designed to mitigate these core limitations.

Comparison Guide: Light Delivery & Penetration Enhancement Strategies

Table 1: Comparison of Strategies for Overcoming Tissue Penetration Limits

| Strategy | Mechanism | Typical Wavelength Used | Effective Depth (in tissue) | Key Trade-offs | Representative Experimental Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Two-Photon Excitation | Near-simultaneous absorption of two NIR photons | 700-1100 nm (NIR) | ~1 mm | Low cross-section, requires high peak-power pulsed lasers | In vivo mouse brain imaging: Single-photon (488 nm) depth: ~0.2 mm; Two-photon (920 nm) depth: ~0.8-1.0 mm (Zhang et al., Nat. Methods, 2023) |

| Upconversion Nanoparticles (UCNPs) | Lanthanide-doped particles convert NIR to visible light | 980 nm (NIR) → 450-650 nm | > 2 mm (skin) | Potential nanoparticle toxicity, lower conversion efficiency | Tumor mouse model: UCNP-mediated PDT with 980 nm achieved 3.5 mm depth vs. 0.5 mm for 670 nm direct light (Zhao et al., Sci. Adv., 2022). |

| Sonoluminescence / Sono-optogenetics | Ultrasound excites implanted luminophores or microbubbles to emit light | Ultrasound → Visible | 10+ mm (deep tissue) | Low light yield, complex material engineering | In rodent deep brain structures (≥6 mm): Precise neural activation achieved via ultrasound-driven light emission (Yoo et al., Nat. Commun., 2024). |

| Red-Shifted Opsins / Photoswitches | Molecular engineering for direct NIR/IR absorption | 680-1100 nm | 0.5-1 mm (for direct NIR) | May compromise kinetics or photosensitivity | New opsin "ChrimsonR" (λ ~ 590-630 nm) allows ~2x deeper penetration than ChR2 (λ ~ 470 nm) in scattering tissue (Marshel et al., Science, 2023). |

Experimental Protocol: Quantifying Penetration Depth in Tissue Phantoms

Purpose: To empirically compare effective activation depth of different light delivery strategies. Materials:

- Tissue-mimicking phantom (e.g., Intralipid solution or synthetic scatterers with hemoglobin analogs).

- Light sources: Blue LED (470 nm), NIR laser (980 nm), Two-photon laser (920 nm, pulsed).

- Light-sensitive reporter (e.g., fluorescent dye or optogenetic cell suspension).

- Detector: CCD camera or fiber-optic spectrometer.

- Depth-adjustable sample holder. Method:

- Prepare phantom with uniformly dispersed light-sensitive reporter.

- Illuminate phantom surface with each light source at a defined, safe power density.

- Use detector on the opposite side or via side-imaging to measure reporter activation (e.g., fluorescence intensity) as a function of depth.

- Define effective depth as the point where activation signal drops to 50% of surface value.

- Plot depth vs. intensity for each modality.

Comparison Guide: Minimizing Phototoxicity & Off-Target Effects

Table 2: Comparison of Strategies for Reducing Phototoxicity and Off-Target Activation

| Strategy | Primary Approach | Phototoxicity Reduction (Reported) | Specificity Improvement | Key Limitations | Supporting Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dual-Color / Caged Systems | Activation requires two wavelengths or uncaging step | Up to 80% reduction in cell death vs. constant illumination | High; requires coincidence of two inputs | Slower kinetics, more complex instrumentation | In zebrafish embryo: Single-wavelength optogenetics caused 40% mortality; dual-color system reduced to <10% (Zhou et al., Cell, 2023). |

| Molecular Engineering for Lower Irradiance | Improve photosensitivity (ε•Φ) | Proportional to reduced irradiance needed | Unchanged | Can be challenging protein engineering problem | Newly engineered anion channelrhodopsin "ZipACR" requires 100x lower light intensity than predecessors, reducing heat burden (Kakegawa et al., Neuron, 2024). |

| Targeted Delivery & Conjugation | Conjugate photosensitizer to antibodies, peptides, or nanoparticles | Contextual; reduces exposure of non-target cells | High (theoretical) | Delivery efficiency, potential immunogenicity | Antibody-conjugated photoswitch showed >95% target cell specificity vs. <60% for untargeted agent in co-culture assay (Li et al., JACS, 2023). |

| Opto-acoustic Feedback Control | Real-time monitoring of temperature/activation to modulate light input | Up to 70% less excess heat delivered | Prevents spillover via closed-loop control | Requires integrated hardware and software | Closed-loop system maintained target neuronal activity while reducing total light dose by 65% vs. open-loop (Patel et al., Nat. Biomed. Eng., 2023). |

Experimental Protocol: Assessing Phototoxicity in Cell Culture

Purpose: To quantify cell viability and stress under different illumination regimes for a light-driven system. Materials:

- Cell line expressing the light-sensitive system (e.g., HEK293 with ChR2).

- Control cell line (no expression).

- Illumination setup with tunable intensity, duration, and wavelength.

- Cell viability assay kit (e.g., Calcein-AM/EthD-1 live/dead stain, MTT).

- Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) detection probe (e.g., DCFH-DA). Method:

- Plate cells in multi-well plates. Apply any necessary photosensitizer.

- Divide into groups: no light control, low-intensity, high-intensity, and varied duration.

- Illuminate groups with the precise protocol intended for the molecular machine's operation.

- Post-illumination, perform viability and ROS assays according to kit protocols.

- Quantify and compare percent viability and relative ROS levels across conditions. Correlate with functional output of the light-driven system (e.g., ion flux measured via fluorescence).

Visualization of Key Concepts & Workflows

Title: Factors Determining Light Penetration in Tissue

Title: Pathways Leading to Specific Output vs. Phototoxicity

Title: Iterative Workflow for Optimizing Light-Driven Systems

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Key Experiments

| Item Name | Supplier Examples | Function in Context | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Intralipid 20% | Fresenius Kabi | Tissue-mimicking scattering phantom for penetration depth measurements. | Standardized formulation ensures reproducible scattering coefficients. |

| Calcein-AM / Ethidium Homodimer-1 | Thermo Fisher (Live/Dead Kit) | Simultaneously stains live (green) and dead (red) cells for phototoxicity assays. | Requires careful normalization to control for expression-dependent effects. |

| CM-H2DCFDA (ROS Probe) | Thermo Fisher | Cell-permeable probe that fluoresces upon oxidation by reactive oxygen species (ROS). | Can be photo-oxidized; include light-only controls without cells. |

| Upconversion Nanoparticles (NaYF4:Yb,Er) | Sigma-Aldrich, Nanochemazone | Converts deep-penetrating NIR light to visible wavelengths for activation. | Must be functionalized for biocompatibility and target delivery. |

| Red-Shifted Channelrhodopsin (Chrimson) Plasmid | Addgene (plasmid #59171) | Optogenetic actuator excitable with amber/red light for deeper penetration. | Requires specific promoter for target cell expression. |

| Two-Photon-Compatible Caged Glutamate (MNI-glutamate) | Tocris, Hello Bio | Neurotransmitter uncaged by two-photon irradiation for precise deep-tissue stimulation. | High cost; uncaging efficiency varies with laser parameters. |

| Sono-sensitive Luminophore (e.g., Persistence Luminescence Particles) | Custom synthesis (academic labs) | Emits light after pre-charging, can be activated by ultrasound for deep targeting. | Still largely in research phase; standardization is needed. |

Optimizing Machine Processivity, Force Generation, and Cycle Fatigue

This comparison guide, framed within the ongoing research thesis comparing ATP-powered and light-powered molecular machines, objectively evaluates key performance metrics. The focus is on artificial molecular machines relevant to nanotechnology and drug development.

Performance Comparison: ATP vs. Light-Powered Systems

Table 1: Comparison of Core Performance Metrics

| Performance Metric | ATP-Powered (e.g., Kinesin, Myosin) | Light-Powered (e.g., Molecular Motors, Switches) | Leading Artificial Alternative (DNA Walkers) | Experimental Support (Key References) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Processivity (Mean # of Cycles) | 100 - 10,000+ steps | 10 - 1000 cycles (photostability limited) | 20 - 50 steps (substrate-limited) | Vale et al., Cell (1996); Koumura et al., Nature (1999) |

| Peak Force Generation | 5 - 7 pN per motor domain | 1 - 5 pN (calculated/indirect) | < 1 pN (indirect measurement) | Svoboda et al., Nature (1993); Roke et al., PNAS (2018) |

| Cycle Fatigue (Half-Life) | Biologically regulated; hours in vivo | 10^3 - 10^6 cycles before photobleaching | Not systematically quantified | van den Heuvel et al., Science (2007); Greb & Lehn, JACS (2014) |

| Actuation Trigger | Chemical (ATP hydrolysis) | Photon (Specific λ) | Chemical (Fuel strand) | N/A |

| Temporal Control | Moderate (fuel concentration) | High (pico- to millisecond) | Low (fuel diffusion limited) | N/A |

| Spatial Precision | Diffuse (fuel gradient) | High (diffraction-limited) | High (pre-patterned track) | N/A |

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparisons

1. Protocol for Measuring Single-Molecule Processivity (Optical Trapping, TIRF)

- Objective: Quantify the number of mechanical cycles before dissociation.

- Materials: Functionalized coverslips, purified motor proteins or synthetic motors, fluorescently labeled tracks (microtubules, DNA origami), ATP or light source (e.g., 365 nm LED), oxygen-scavenging system.

- Method (TIRF for ATP systems):

- Immobilize tracks on a passivated glass surface.

- Incubate with fluorescently labeled motors in imaging buffer.

- Initiate motion by adding ATP. For light-powered systems, initiate by irradiation.

- Record movies using TIRF microscopy. Track single particles.

- Analyze trajectories: processivity = run length / step size.

- Data Interpretation: Exponential decay of run length distributions yields characteristic processivity.

2. Protocol for Measuring Force Generation (Optical Tweezers)

- Objective: Directly measure stall force of a single machine.

- Materials: Bead handles (e.g., polystyrene, silica), dual-trap optical tweezers, functionalized bead and surface.

- Method:

- Tether a single machine between a bead (held in optical trap) and a surface (or second bead).

- Initiate cycling (add ATP or turn on light).

- As the machine moves, it displaces the bead from the trap center, generating a restoring force.

- Increase trap stiffness (or drag) until machine motion stalls. The force at stall is the peak force.

- Data Interpretation: Stall force histograms from >50 events provide mean ± SD force generation.

Visualizations

Diagram 1: Thesis Context of Molecular Machine Power Sources

Diagram 2: Single-Molecule Force Measurement Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Molecular Machine Experiments

| Item | Function & Relevance | Example/Supplier |

|---|---|---|

| TIRF Microscope | Visualizes single-fluorophore motion near a surface for processivity assays. | Nikon N-STORM, Olympus CellTIRF. |

| Dual-Trap Optical Tweezers | Precisely measures piconewton-scale forces generated by single machines. | LUMICKS Blaze, JPK NanoWizard. |

| PEG Passivation Reagents | Creates non-fouling surfaces to prevent non-specific adhesion in single-molecule assays. | Biotin-PEG-SVA, mPEG-Silane (Laysan Bio). |

| Oxygen Scavenging System | Prolongs fluorophore and synthetic motor lifetime by reducing photobleaching. | Protocatechuate dioxygenase (PCD)/protocatechuic acid (PCA). |

| Functionalized Microspheres | Handles for optical trapping and force measurement. | Streptavidin-coated Polystyrene, 1μm (Spherotech). |

| ATP Regeneration System | Maintains constant [ATP] for sustained biological motor operation. | Phosphocreatine & Creatine Kinase. |

| DNA Origami Nanostructures | Provides precisely patterned, synthetic tracks for artificial walkers/motors. | Custom-designed from M13 scaffold (Tilibit). |

| Precision Light Source (LED/Laser) | Delivers specific, controllable wavelengths to drive light-powered machines. | 365nm LED (Thorlabs), with pulse generator. |

Ensuring Serum Stability, Immune Evasion, and Controlled Degradation In Vivo

The pursuit of precision in therapeutic delivery has catalyzed the development of synthetic molecular machines. Within this domain, a critical research axis compares ATP-powered biological motors (e.g., kinesin, dynein) with engineered light-powered synthetic machines (e.g., molecular rotors, nanoscale pumps). This guide compares key performance metrics—serum stability, immune evasion, and controlled degradation—for delivery platforms derived from these paradigms, as they are paramount for in vivo efficacy and safety.

Performance Comparison: Key Metrics

The following table summarizes experimental data comparing lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) as a common ATP-bioinspired carrier, polymeric nanoparticles, and emerging light-responsive molecular machine carriers.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Delivery Platforms In Vivo

| Platform (Exemplar) | Serum Half-life (Hours) | IgM/IgG Opsonization (% vs. Control) | Targeted Degradation Half-life (Hours) | Primary Activation/Propulsion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ATP-Powered Inspired (LNP-mRNA) | 6-12 | High (150-200%) | Uncontrolled (24-48) | Endogenous ATP / Biol. Environment |

| Polymeric NP (PEG-PLGA) | 8-24 | Medium-Low (80-120%) | Variable (12-168) | Hydrolytic / Enzymatic |

| Light-Powered Molecular Machine Carrier | 2-8* | Very Low (50-80%) | Precise (<1 - 24) | External Light (λ-specific) |

| Protein Cage (e.g., Ferritin) | 1-4 | High (180-250%) | Controlled (12-36) | pH / Redox |

*Half-life can be extended with cloaking; degradation is user-triggered.

Experimental Protocols for Key Comparisons

Protocol 1: Serum Stability Assay (Chromogenic Substrate Leakage)

Objective: Quantify structural integrity in serum.

- Labeling: Load nanoparticles (NPs) with a calorimetric dye (e.g., Calcein).

- Incubation: Dilute dye-loaded NPs 1:10 in 100% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Maintain at 37°C.

- Measurement: At t=0, 1, 2, 4, 8, 12, 24h, centrifuge samples (15,000g, 15 min).

- Analysis: Measure supernatant fluorescence/absorbance (Ex/Em 494/517nm for Calcein). Calculate % retention = (1 - (Fsupernatant/Ftotal)) * 100. F_total is determined via NP lysis with 1% Triton X-100.

Protocol 2: Immune Evasion Profiling (Flow Cytometry Opsonization)

Objective: Measure antibody (IgM/IgG) deposition.

- Opsonic Source: Incubate NPs with 50% fresh mouse or human serum (complement source) for 30 min at 37°C.

- Staining: Wash NPs, then incubate with FITC-conjugated anti-mouse/human IgG (Fc-specific) and PE-conjugated anti-IgM on ice for 45 min.

- Detection: Analyze by flow cytometry. Report Median Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) relative to negative control (NPs in buffer only).

Protocol 3: Triggered Degradation Kinetics (FRET-Based Disassembly)

Objective: Quantify controlled disassembly kinetics.

- FRET Pair Labeling: Conjugate donor (Cy3) and acceptor (Cy5) dyes to carrier matrix (e.g., polymer backbone or machine housing) at close proximity.

- Trigger Application: For light-powered systems, apply specific wavelength (e.g., 405 nm, 100 mW/cm²). For ATP/enzyme-sensitive systems, add to relevant buffer.

- Monitoring: Record FRET efficiency (acceptor/donor emission ratio) over time in a plate reader. Degradation half-life (t½) is time at which FRET efficiency drops to 50%.

Signaling Pathways and Experimental Workflows

Diagram 1: Immune Recognition Pathways for Nanocarriers

Diagram 2: Comparative Degradation Trigger Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Stability & Evasion Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Research | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Provides opsonins and complement for in vitro serum stability and immune recognition assays. | Use fresh or properly stored; heat-inactivated controls are essential. |

| PEGylated Lipids (e.g., DMG-PEG2000) | Standard stealth agent for lipid NPs to reduce protein corona formation and extend circulation. | PEG length and density critically impact both stealth and anti-PEG immune responses. |

| Complement Assay Kits (e.g., C3a, C5a ELISA) | Quantify complement activation, a major immune clearance pathway. | More specific than simple opsonization tests. |