Overcoming the Scale-Up Barrier: Key Challenges and Advanced Solutions in Molecular Engineering

Scaling molecular engineering processes from laboratory discovery to industrial and clinical application presents a complex set of interdisciplinary challenges.

Overcoming the Scale-Up Barrier: Key Challenges and Advanced Solutions in Molecular Engineering

Abstract

Scaling molecular engineering processes from laboratory discovery to industrial and clinical application presents a complex set of interdisciplinary challenges. This article explores the foundational hurdles in fabrication, stability, and system integration that hinder scale-up. It delves into cutting-edge methodological solutions, including hybrid AI-mechanistic modeling, machine learning-guided design, and advanced computational simulations. The content provides a practical troubleshooting framework for optimizing processes and discusses rigorous validation strategies for cross-scale comparability. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current knowledge to offer a roadmap for navigating the critical path from nanoscale innovation to mass production and therapeutic impact.

The Fundamental Hurdles: Why Scaling Molecular Processes Fails

In molecular engineering, a persistent and fundamental challenge is the loss of precise control when scaling processes from the nano- to the macroscale. At the nanoscale, researchers can manipulate individual molecules and structures with high precision, exploiting unique physical and chemical phenomena. However, maintaining this fine level of control over material properties, reaction kinetics, and structural fidelity in larger-volume production systems often proves difficult. This diminishing control presents a critical bottleneck in translating laboratory breakthroughs into commercially viable products, particularly in pharmaceuticals and advanced materials.

The core of this conundrum lies in the shift in dominant physical forces. In macroscale systems, volume-dependent forces such as gravity and inertia dominate, while at the nanoscale, surface-dependent forces including electrostatics, van der Waals forces, and surface tension become predominant [1]. This transition in force dominance explains why simply "scaling up" a nanoscale process frequently leads to unexpected behaviors and inconsistent results.

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Control Loss in 3D Printed Nanostructured Materials

Problem: During the scale-up of 3D printed materials designed with nanoscale features, the bulk mechanical properties do not match those predicted from nanoscale testing or small-scale prototypes.

Identification: The macroscopic 3D printed object exhibits poor mechanical performance despite characterization showing correct nanoscale morphology in small samples [2] [3].

Systematic Troubleshooting Approach:

Verify Nanostructure Consistency Across Scales

- Action: Use Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) to characterize nanoscale morphology at different locations in the macroscopic object and compare with small-scale reference samples [1].

- Expected Result: Consistent domain sizes and morphologies across all sample locations.

- Failure Indication: Variations in domain size or transition from bicontinuous to discrete globular domains explains mechanical property degradation [2] [3].

Analyze Polymerization Kinetics

- Action: Monitor double bond conversion (α) during the photopolymerization process at different depths and in larger resin vats. Compare kinetics with small-scale successful batches.

- Expected Result: Similar polymerization kinetics (e.g., α ≈ 84% after 30s and ≈ 91% after 60s for PBA94-CTA at 16.5 wt% loading) regardless of production scale [3].

- Failure Indication: Slower polymerization kinetics in larger batches suggests issues with photoinitiator distribution or light penetration, affecting nanostructure formation.

Check Resin Component Homogeneity

- Action: Assess macromolecular chain transfer agent (macroCTA) distribution and aggregation state in large-volume resin preparations before printing.

- Expected Result: Homogeneous, transparent resin mixtures with consistent viscosity values corresponding to small-scale batches (e.g., viscosity increases with both macroCTA Xn and wt%) [3].

- Failure Indication: Phase separation or viscosity variations in the resin before printing leads to inconsistent microphase separation during polymerization.

Resolution: If the investigation reveals inconsistent nanostructure as the root cause, adjust the macroCTA chain length and concentration to maintain the optimal polymer volume fraction that produces bicontinuous domains, which provide enhanced mechanical properties compared to discrete domains [3].

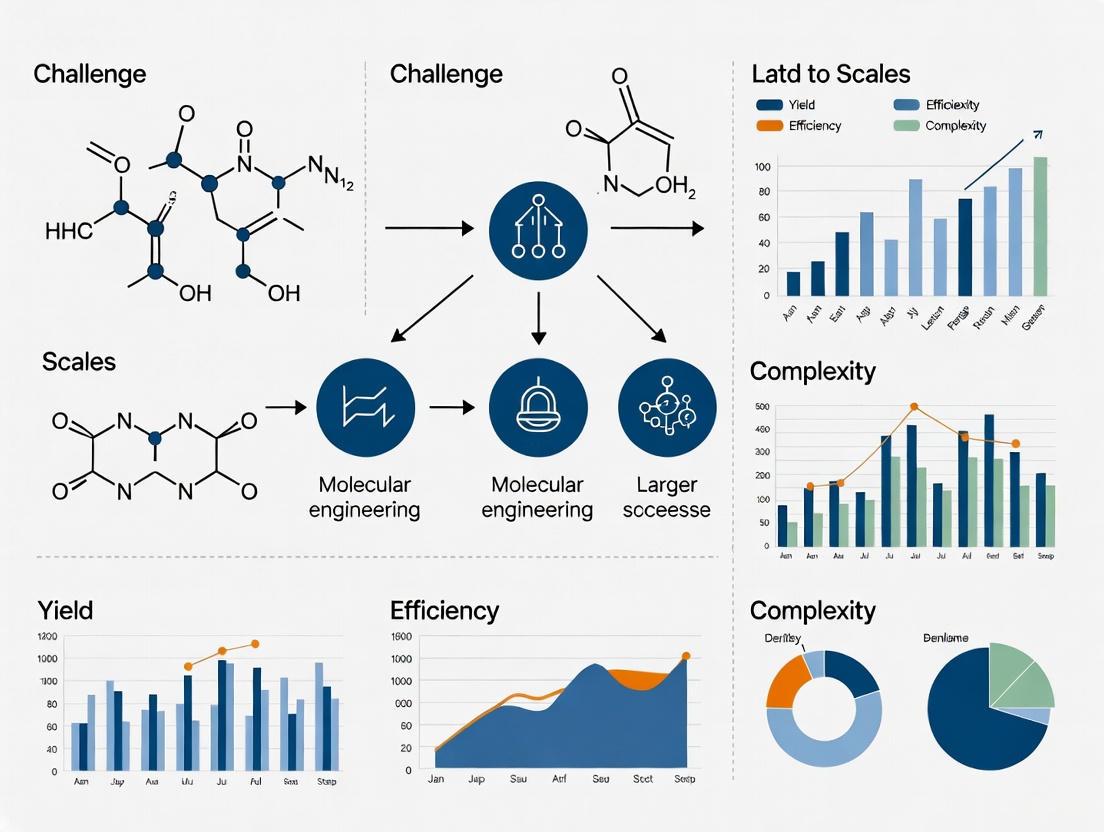

Diagram 1: Troubleshooting loss of nanoscale control in 3D printing scale-up.

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Microreactor to Macroscale Translation

Problem: A chemical synthesis process that achieves high yield and selectivity in a microreactor system suffers from decreased efficiency and product quality when transferred to a large-scale batch reactor.

Identification: The scaled-up process shows lower conversion rates, increased byproducts, and potential thermal runaway in exothermic reactions [1].

Systematic Troubleshooting Approach:

Profile Heat and Mass Transfer Parameters

- Action: Quantify and compare key parameters between systems. Calculate the surface-to-volume ratio (S/V) and measure temperature gradients.

- Expected Result: Minimal temperature variations (±1-2°C) throughout the reaction mixture.

- Failure Indication: Significant temperature gradients (hot spots >5°C variation) and lower S/V ratio in the large-scale reactor confirm heat transfer limitations [1].

Evaluate Mixing Efficiency

- Action: Perform chemical tracer tests to determine mixing times and identify potential dead zones in the large-scale reactor.

- Expected Result: Complete mixing within the designed timeframe.

- Failure Indication: Segregated regions or extended mixing times lead to inconsistent reactant concentrations and byproduct formation.

Assess Flow Dynamics and Residence Time Distribution

- Action: Compare the residence time distribution (RTD) between the microreactor and large-scale system.

- Expected Result: Narrow RTD similar to microreactor plug-flow characteristics.

- Failure Indication: Broad RTD indicates flow irregularities, reducing effective reaction control.

Resolution: If heat transfer limitations are identified, implement process intensification strategies such as segmented flow, advanced agitator designs, or additional cooling surfaces to better approximate microreactor conditions [1].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: Why do molecular machines that function precisely at the nanoscale often fail to maintain that precision when integrated into larger systems?

A1: The primary reason is the transition from deterministic to stochastic control. At the nanoscale, molecular machines operate through specific chemical interactions and short-range forces, where control is direct and precise. In larger assemblies, the cumulative effect of thermal fluctuations, statistical variations in molecular orientations, and inconsistent energy distribution across the system introduces randomness that diminishes overall precision and reliability [4].

Q2: What are the most common factors that disrupt nanoscale morphology during the scale-up of 3D printed materials?

A2: The key factors include:

- Inconsistent polymerization kinetics due to variations in photoinitiator effectiveness or light penetration in larger resin vats [3].

- Macromolecular chain transfer agent (macroCTA) aggregation or incomplete mixing in large-batch resin formulations, leading to heterogeneous domain structures [2] [3].

- Variations in viscosity and diffusion rates during the polymerization induced microphase separation (PIMS) process, altering the self-assembly dynamics of block polymers [3].

Q3: How does the surface-area-to-volume ratio impact scalability from micro/nano to macro scales?

A3: The surface-area-to-volume ratio follows an inverse relationship with scale. As the characteristic length (L) of a system increases, the ratio decreases proportionally (as 1/L) [1]. This has profound implications:

- Heat and Mass Transfer: Rates that are exceptionally high at micro/nano scales become significantly slower at macro scales.

- Force Dominance: Surface forces (electrostatic, capillary) that dominate at small scales give way to body forces (gravity, inertia) at larger scales.

- Control Precision: The high surface-area-to-volume ratio at small scales enables more uniform and rapid control of process parameters, which diminishes with increasing scale.

Q4: What strategic approaches can mitigate scalability control loss in molecular engineering?

A4: Successful strategies include:

- Numbering-Up vs. Scaling-Up: Using multiple parallel microreactors instead of a single large reactor maintains the beneficial characteristics of the small scale [1].

- Hierarchical Design: Creating systems that preserve nanoscale control mechanisms through modular integration rather than homogeneous expansion.

- Advanced Process Analytics: Implementing in-line monitoring techniques (e.g., AFM, Raman spectroscopy) to detect and correct nanostructural deviations in real-time during scale-up.

Quantitative Data: Scaling Effects on Material Properties

Table 1: Effect of MacroCTA Chain Length on Nanostructure and Mechanical Properties in 3D Printing [3]

| MacroCTA Degree of Polymerization (Xn) | Nanoscale Domain Size | Primary Morphology | Relative Mechanical Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 24 | 10-20 nm | Discrete Globular | Low |

| 48 | 20-35 nm | Elongated Discrete | Medium |

| 94 | 35-50 nm | Bicontinuous | High |

| 180 | 50-70 nm | Bicontinuous | High |

| 360 | 70-100 nm | Bicontinuous | Medium |

Table 2: Scaling Effects from Micro/Nano to Macro Systems [1]

| Parameter | Scaling Law | Impact on Process Control |

|---|---|---|

| Surface-to-Volume Ratio | Decreases with 1/L | Reduced control: Lower heat and mass transfer rates, leading to temperature gradients and concentration inhomogeneity. |

| Gravitational Force | Increases with L³ | Increased sedimentation: Enhanced particle settling and stratification in large-scale systems. |

| Surface Tension | Constant | Relative force shift: Becomes less dominant compared to body forces, altering fluid behavior. |

| Flow Characteristics | Transition from laminar to turbulent | Mixing alteration: Changes in flow patterns affect reaction homogeneity and product distribution. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Nanostructure-Controlled 3D Printing [3]

| Reagent/Material | Function | Scalability Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Macromolecular Chain Transfer Agent (MacroCTA) | Controls nanoscale microphase separation during polymerization; determines domain size and morphology. | Batch consistency critical: Requires rigorous characterization (Mn, Ɖ) across production scales. |

| Poly(Ethylene Glycol) Diacrylate (PEGDA) | Crosslinking monomer that forms the rigid matrix; impacts polymerization kinetics and final mechanics. | Viscosity control: Higher volumes may require modified handling to maintain printing resolution. |

| Photoinitiator (e.g., TPO) | Generates radicals upon light exposure to initiate polymerization; concentration affects reaction rate. | Light penetration limits: Concentration may need optimization for larger vat geometries. |

| n-Butyl Acrylate (BA) | Monomer used to synthesize PBA-CTA; forms the soft block in the resulting nanostructured material. | Purity essential: Trace impurities can significantly alter nanoscale self-assembly behavior. |

Industry Context: Scalability in Cell and Gene Therapy

The scalability conundrum is particularly acute in the rapidly advancing field of cell and gene therapy. In 2025, the industry continues to face significant challenges in scaling laboratory processes to commercial manufacturing scales while maintaining precise control over product quality and consistency [5]. The translation from small-scale experimental systems to large-scale production presents hurdles in process control, monitoring, and reproducibility that directly parallel the fundamental nano-to-macro control diminishment discussed in this article. These scalability challenges impact commercial viability and patient access to breakthrough therapies [5].

In molecular engineering and nanomaterial science, self-assembly represents a fundamental bottom-up approach for constructing complex structures from smaller subunits, such as nanoparticles, proteins, and nucleic acids [6]. This process is defined as the spontaneous organization of components into defined and organized structures without human intervention, driven by interactions to achieve thermodynamic equilibrium [6]. While self-assembly offers significant benefits for nanofabrication, including scalability, cost-effectiveness, and high reproducibility potential, several critical challenges impede its reliable implementation at scale [6]. The central obstacles include the presence of parasitic products and long-lived intermediate states that slow reaction processes and limit final product yield [7], difficulties in controlling processes on large scales while maintaining reproducibility [6], and insufficient understanding of fundamental thermodynamic and kinetic mechanisms at the nanoscale [6]. These challenges become particularly pronounced when transitioning from laboratory-scale proof-of-concept demonstrations to industrially relevant production volumes, where yield and reproducibility become economically critical parameters.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are parasitic products in self-assembly systems, and why do they reduce yield? Parasitic products are incorrectly assembled structures that form when subunits interact in non-ideal configurations during the self-assembly process [7]. These unwanted byproducts consume starting materials without contributing to the desired final structure, thereby significantly reducing the overall yield [7]. Unlike the final product, parasitic products often represent metastable states that persist throughout the assembly process, creating kinetic traps that prevent the system from reaching the thermodynamically optimal configuration.

Q2: How does kinetic trapping affect self-assembly reproducibility? Kinetic trapping occurs when assemblies become stuck in metastable states instead of progressing to the global free energy minimum [6]. This phenomenon leads to pathway-dependent outcomes, where the final structure depends not just on the starting conditions but on the specific kinetic pathway taken [6]. This sensitivity to initial conditions and environmental fluctuations directly undermines reproducibility, as identical starting materials can yield different structural outcomes across experimental runs due to variations in formation kinetics.

Q3: What role do thermodynamic parameters play in achieving high-yield self-assembly? Self-assembly is governed by the Gibbs free energy equation ΔGSA = ΔHSA - TΔSSA, where a negative ΔGSA drives the spontaneous assembly process [6]. The balance between enthalpy (ΔHSA, representing intermolecular interactions) and entropy (-TΔSSA, representing disorder) determines the feasibility and efficiency of assembly. For high yields, the thermodynamic driving force must be sufficient to overcome entropic losses while allowing sufficient molecular mobility for components to find their correct positions. This delicate balance makes self-assembly highly sensitive to temperature, concentration, and environmental conditions.

Q4: What are the main types of defects in self-assembled structures? Self-assembled structures typically contain both equilibrium defects and non-equilibrium defects [6]. Equilibrium defects exist because the free energy of defect formation (ΔGDF = ΔHDF - TΔSDF) can be negative at experimental temperatures, making some defects thermodynamically favorable [6]. Non-equilibrium defects arise from kinetic limitations during assembly and represent metastable configurations. Current research focuses on controlling defect density through manipulation of assembly conditions and implementation of error-correction mechanisms [6].

Q5: How can proofreading strategies improve self-assembly yields? Recent research demonstrates that proofreading mechanisms can significantly enhance yield and time-efficiency in microscale self-assembly [7]. By designing intermediate states that strongly couple to external forces while creating final products that decouple from these forces, external driving can selectively dissociate parasitic products while leaving correct assemblies intact [7]. This approach, inspired by biological systems, enables error correction during the assembly process rather than relying solely on perfect initial conditions.

Troubleshooting Guide for Common Self-Assembly Challenges

Problem: Low Yield of Target Structure

- Symptoms: Low conversion of starting materials to desired product; high proportion of incomplete or malformed structures; presence of persistent intermediates.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution Approach |

|---|---|---|

| High concentration of parasitic products | Lack of error correction mechanisms | Implement magnetic decoupling proofreading: design intermediates responsive to external fields while final product is field-insensitive [7] |

| Slow assembly kinetics | Insufficient thermal energy for reorganization | Optimize temperature profile to balance mobility and stability; consider stepped temperature protocols |

| Incomplete assembly | Suboptimal stoichiometry or concentration | Systematically vary component ratios; determine optimal concentration window for nucleation vs. growth |

Problem: Poor Reproducibility Between Experimental Runs

- Symptoms: Variable structural outcomes from identical starting materials; inconsistent yield measurements; unpredictable defect densities.

- Potential Causes and Solutions:

| Symptom | Potential Cause | Solution Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Pathway-dependent outcomes | Kinetic trapping in metastable states | Implement annealing protocols (thermal or field-based) to enable error correction [6] |

| Sensitivity to minor environmental fluctuations | Inadequate process control | Standardize mixing protocols, temperature ramps, and container surfaces; implement environmental monitoring |

| Variable defect density | Insufficient understanding of defect thermodynamics | Characterize defect formation energy; adjust temperature to manipulate ΔGDF [6] |

Advanced Technique: Magnetic Proofreading for Enhanced Yield

The recently developed magnetic decoupling strategy provides a powerful approach to address yield limitations in self-assembly systems [7]. This methodology can be implemented as follows:

- Protocol Objective: Selective dissociation of parasitic products to increase yield of target structure

- Materials: Lithographically patterned magnetic dipoles, oscillating magnetic field source, assembly components with responsive elements

- Methodology:

- Design intermediate assembly states with strong coupling to magnetic fields

- Engineer final product with minimal field interaction (decoupled state)

- Apply patterned magnetic driving to selectively destabilize incorrect assemblies

- Optimize field parameters (frequency, amplitude, waveform) for maximum discrimination

- Implement cycling between assembly and proofreading phases

- Key Parameters: Field strength: 10-100 mT; Frequency: 0.1-10 Hz; Duration: Cyclic intervals of 5-30 minutes

- Expected Outcomes: 30-70% yield improvement; significant reduction in parasitic products; faster time to complete assembly [7]

Experimental Protocols for High-Yield Self-Assembly

Thermodynamic Control Protocol for Defect Management

Defect formation is an inherent aspect of self-assembly processes, governed by the equation ΔGDF = ΔHDF - TΔSDF [6]. This protocol enables thermodynamic control of defect density:

- Step 1: Determine the defect formation enthalpy (ΔHDF) for your system using structural analysis techniques

- Step 2: Calculate the temperature at which ΔGDF becomes positive (T < ΔHDF/ΔSDF) to suppress thermodynamically favorable defects

- Step 3: Implement controlled cooling protocols to minimize kinetic defects

- Step 4: Characterize defect density using appropriate analytical methods (e.g., microscopy, scattering)

- Step 5: Iteratively adjust temperature profile to optimize defect density while maintaining practical assembly timescales

Kinetic Pathway Engineering Protocol

To address challenges with kinetic trapping and pathway-dependent outcomes [6]:

- Step 1: Map potential energy landscape of assembly process to identify metastable states

- Step 2: Design seeding strategies to bypass high-energy nucleation barriers

- Step 3: Implement multi-stage assembly with intermediate annealing steps

- Step 4: Utilize external fields (magnetic, electric, acoustic) to guide pathway selection

- Step 5: Monitor pathway progression in real-time using in-situ characterization techniques

Research Reagent Solutions for Self-Assembly Systems

| Reagent / Material | Function in Self-Assembly | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Lithographically patterned magnetic dipoles | Provides spatially controlled magnetic fields for directed assembly and proofreading [7] | Enables magnetic decoupling strategy for yield improvement |

| Field-responsive nanoparticles | Building blocks with tunable interaction with external fields | Allows external control over assembly pathways and error correction |

| Block copolymers | Model system for studying self-assembly thermodynamics and kinetics [6] | Useful for fundamental studies of defect formation and pathway dependence |

| DNA origami tiles | Programmable subunits with specific binding interactions [7] | Enables complex shape formation with high specificity |

| Fluorescent quantum dots | Tracking and visualization of assembly progression [6] | Facilitates real-time monitoring of assembly pathways and intermediate states |

Workflow Diagrams for Self-Assembly Optimization

Magnetic Proofreading Workflow

Defect Formation Thermodynamics

Self-Assembly Kinetic Pathways

Technical Support Center

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most common causes of unreliable electrical contact in single-molecule junctions?

Unreliable electrical contact is primarily caused by the inherent challenges in establishing reproducible electrical contact with only one molecule without shortcutting the electrodes. Conventional photolithography is unable to produce electrode gaps small enough (on the order of nanometers) to contact both ends of the molecules. Furthermore, the use of sulfur anchors to gold, while common, is non-specific and leads to random anchoring. The contact resistance is highly dependent on the precise atomic geometry around the anchoring site, which inherently compromises the reproducibility of the connection [8].

FAQ 2: What strategies can improve signal-to-noise ratios in molecular computing devices?

Molecular computing devices operate at extremely low energy levels, making them highly susceptible to noise. Effective noise reduction strategies include [9]:

- Error Correction Codes: Implementing error correction codes and redundancy at the molecular level to detect and correct noise-induced errors.

- Shielding and Isolation: Employing shielding and isolation techniques to minimize the influence of external noise sources.

- Materials and Design: Utilizing advances in materials science and device design to develop noise-resistant molecular components and architectures.

FAQ 3: How can we address the thermal stability of molecular devices?

Molecular devices must maintain structural and functional integrity under thermal fluctuations. Strategies to enhance thermal stability include [9]:

- Material Selection: Careful selection of materials and optimization of intermolecular forces.

- Robust Architectures: Using covalent bonding, cross-linking, and thermally robust molecular architectures, such as heat-resistant molecular switches.

- Temperature Compensation: Developing temperature-compensated molecular circuits to ensure reliable operation across a wide temperature range.

FAQ 4: What are the main challenges in integrating molecular components with silicon-based electronics?

The primary challenge in creating hybrid molecular-silicon devices is the reliable and reproducible fabrication of molecular-silicon interfaces. This includes achieving compatibility between molecular and silicon processing techniques. A significant issue is the size and impedance mismatch between molecular-scale and macroscale components, which requires novel interface designs like molecular wires and nanoelectrodes to bridge the gap [10] [9].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Low Yield in Molecular Self-Assembly for Device Fabrication

- Problem: Inconsistent or low yields when using molecular self-assembly to build complex molecular structures.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Poor control over molecular interactions and environmental conditions.

- Solution: Precisely engineer molecular interactions and tightly control environmental parameters such as temperature, pH, and concentration during the assembly process [9].

- Cause: Lack of reproducibility in the self-assembly process.

- Solution: Develop standardized protocols for molecular self-assembly to achieve higher yields and scalability for practical applications [9].

Issue 2: Signal Attenuation in Molecular-Scale Interconnects

- Problem: Electrical signals are significantly weakened when transmitted through molecular wires and interconnects.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: High impedance and inherent power dissipation in molecular-scale systems.

- Solution: Design and utilize conductive molecules or molecular assemblies with optimized electronic properties for signal transmission. Signal amplification techniques, such as molecular operational amplifiers, may be required to overcome inherent attenuation [10] [9].

- Cause: Unstable or poorly aligned molecular interconnects.

- Solution: Improve the controlled assembly and alignment of molecular interconnects to enhance stability and reliability under operating conditions [10].

Issue 3: Rapid Degradation of Molecular Device Performance

- Problem: Molecular devices experience a rapid decline in performance or complete failure over a short period.

- Possible Causes & Solutions:

- Cause: Chemical degradation due to environmental exposure (e.g., oxidation, humidity).

- Solution: Implement advanced passivation techniques to protect molecular components from the environment [11].

- Cause: Mechanical stress and wear from extended operation.

- Solution: Investigate and incorporate self-repair and self-healing capabilities into molecular systems to enhance their long-term reliability [9].

- Action: Conduct accelerated aging tests and long-term stability studies to understand failure mechanisms and assess device reliability under various operating conditions [9].

Experimental Data & Protocols

Table 1: Core Challenges in Scaling Molecular Computing Devices [9]

| Challenge Category | Specific Challenge | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Fabrication & Integration | Controlling molecular self-assembly | Precise engineering of molecular interactions and environmental conditions (temp, pH, concentration) |

| Fabrication & Integration | Significant size/impedance mismatch with macroscale systems | Novel interface designs (molecular wires, nanoelectrodes) |

| Signal Processing | Low operating energy levels requiring signal amplification | Molecular switches/transistors as building blocks for amplification circuits; enzymatic cascades |

| Signal Processing | High sensitivity to noise (thermal, electronic) | Error correction codes; shielding and isolation techniques |

| Device Stability & Reliability | Structural disruption from thermal fluctuations | Covalent bonding, cross-linking, thermally robust molecular architectures |

| Device Stability & Reliability | Degradation from chemical/mechanical stress | Self-repair mechanisms; advanced passivation; accelerated aging tests |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Electronics

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| Gold Electrodes | Substrate for anchoring molecules via thiol groups [8] | High affinity for sulfur; facilitates electrical contact |

| Conductive Polymers (e.g., PEDOT, Polyaniline) | Used in antistatic materials, displays, batteries, and transparent conductive layers [8] | Processable by dispersion; tunable electrical conductivity via doping |

| Molecular Wires (e.g., Oligothiophenes, DNA) | Provide electrical connection between molecular components and larger circuitry [10] [12] | Conductive molecules; enables electron transfer over long distances (e.g., DNA over 34 nm) |

| Semiconductor Nanowires (e.g., InAs/InP) | Electrodes for contacting organic molecules, allowing for more tailored properties [8] | Semiconductor-only electrodes with embedded electronic barriers |

| Fullerenes (e.g., C₆₀) | Alternative anchoring group for molecules on gold surfaces [8] | Large conjugated π-system contacts more atoms, potentially improving reproducibility |

| Pillar[5]arenes | Supramolecular hosts that can enhance charge transport when complexed with cationic molecules [8] | Can achieve significant current intensity enhancement (e.g., two orders of magnitude) |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Establishing Single-Molecule Junctions

Objective: To form a reliable metal–molecule–metal junction for measuring charge transport through a single molecule.

Methodology: STM-Based Break Junction [8]

Substrate Preparation:

- Begin with a clean, flat gold substrate (e.g., Au(111)).

- Prepare a dilute solution of the molecule of interest, typically functionalized with anchoring groups (e.g., thiols, amines).

- Deposit a droplet of the molecular solution onto the gold substrate and allow sufficient time for the molecules to adsorb onto the surface, forming a self-assembled monolayer.

Junction Formation:

- Use a scanning tunneling microscope (STM) with a gold-coated tip.

- Approach the STM tip to the molecular layer until a stable tunneling current is established.

- Retract the tip slowly from the substrate. During retraction, metal atoms form a nanowire bridge that eventually thins and breaks.

Molecular Trapping:

- As the gap between the tip and substrate narrows to a few nanometers—matching the length of the target molecule—a molecule can bridge the gap, forming a stable junction.

- This is often observed as a plateau in the conductance vs. distance curve, where the conductance remains relatively constant over a specific distance corresponding to the molecular length.

Data Collection & Analysis:

- Measure the current (I) as a function of the applied bias voltage (V) across the junction to obtain I-V characteristics.

- Perform thousands of such breaking cycles to build a statistical histogram of conductance values, where a peak indicates the most probable conductance value for the single molecule.

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Single-Molecule Junction Measurement Workflow

Hybrid Molecular-Silicon Device Architecture

Material and Structural Instability Under Scaling Thermal and Environmental Stress

FAQs: Fundamentals of Stress in Scaled Systems

Q1: What is the primary cause of material instability under thermal stress during process scaling?

The primary cause is the development of thermal stresses due to non-uniform heating or cooling, or from uniform heating of materials with non-uniform properties [13]. During scaling, these effects are magnified. When a material is heated and cannot expand freely, the increased molecular activity generates internal pressure against constraints. The resulting stress is quantifiable; for a constrained material, the thermal stress (F/A) can be calculated as F/A = E * α * ΔT, where E is the modulus of elasticity, α is the coefficient of thermal expansion, and ΔT is the temperature change [13]. In scaled systems, managing the resulting tensile and compressive stresses is critical to prevent fatigue failure, cracking, or delamination.

Q2: How does rapid temperature change (thermal shock) specifically damage materials at the micro-scale? Thermal shock subjects materials to rapid, extreme temperature fluctuations, inducing high stress from differential thermal expansion and contraction [14] [13]. At the micro-scale, this is particularly severe for interfaces between different materials. The stress can cause micro-cracks in solder joints, fractures in plated-through holes (PTHs), and delamination between material layers [15]. For instance, a rapid transition from -40°C to +160°C can increase PTH failure rates by 30% due to CTE (Coefficient of Thermal Expansion) mismatches [15].

Q3: What is the relationship between a material's Coefficient of Thermal Expansion (CTE) and its susceptibility to thermal stress?

A material's CTE directly determines the amount of strain (ΔL/L) it experiences for a given temperature change (ΔT), as per ΔL/L = α * ΔT [13]. Susceptibility to thermal stress is highest in assemblies where joined materials have significantly mismatched CTEs. For example, in a multilayer PCB, a substrate with a high CTE bonded to a conductor with a low CTE will experience severe stress at their interface during temperature cycles, leading to failure [15]. Selecting materials with similar CTEs is therefore a fundamental design strategy for reliability.

Q4: Why does scaling a process from lab to industrial production often exacerbate environmental stress failures? Laboratory-scale prototypes often operate in controlled, benign environments. Industrial scaling introduces harsher and more variable environmental stresses, including broader temperature swings, mechanical vibration, and humidity [16] [17]. Furthermore, smaller, latent defects (e.g., micro-fractures, weak solder joints) that are tolerable at small scale are amplified in larger systems or over larger production volumes. Techniques like Environmental Stress Screening (ESS) are used in production to precipitate these latent defects into observable failures before the product reaches the customer [16].

Q5: Within a thesis on molecular engineering, why is studying these macro-scale stresses relevant? The principles of thermal and environmental stress are universal across scales. Understanding how bulk materials fail under stress provides critical insights for molecular engineering. For instance, research into molecular machines—synthetic or biological systems that perform specific functions—must account for how these nanoscale structures respond to external energy sources like heat or light [4]. The challenges of CTE mismatch in a PCB mirror the challenges of ensuring the structural integrity of a synthetic molecular motor under thermal activation. Mastering macro-scale stress analysis provides a foundational framework for designing stable and reliable molecular-scale systems.

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Diagnosing and Resolving Thermal Cycling Failures

Problem: Cracks in interconnects, solder joints, or vias observed after repeated temperature cycles.

Investigation & Diagnosis:

- Visually Inspect: Use a microscope (at least 10X magnification) to inspect all critical surfaces and interfaces for micro-cracks, especially after stress screening [16].

- Perform Functional Testing: Verify the component operates within design tolerances before, during, and after thermal cycling tests [16].

- Analyze the Failure: Cross-section the failed joint or via to examine crack propagation. This often reveals a CTE mismatch between the joined materials [15].

Solution:

- Material Selection: Choose substrate, conductor, and solder materials with closely matched Coefficients of Thermal Expansion (CTE) [15]. Refer to Table 1 for common material properties.

- Design Optimization: Implement low-aspect-ratio vias with adequate copper plating thickness to reduce stress concentration [15].

- Process Control: Ensure manufacturing and repair processes meet high workmanship standards to avoid introducing defects [16].

Guide 2: Addressing Catastrophic Failure Under Thermal Shock

Problem: Sudden, catastrophic failure (e.g., material fracture, delamination) upon exposure to a rapid temperature transition.

Investigation & Diagnosis:

- Recreate the Shock: Subject the unit to a controlled thermal shock test, such as moving it between chambers at -55°C and +150°C in seconds [14] [15].

- Identify Weak Points: The failure is likely at the most brittle material or the interface with the greatest CTE mismatch. Non-uniform cooling or heating of a uniform material is a typical cause [13].

Solution:

- Use Robust Materials: For high-temperature applications, switch to ceramics or metal-core substrates which have lower CTEs and higher thermal stability than standard FR-4 [15].

- Moderate Operational Transients: Implement controlled heating and cooling rates in operational procedures to minimize thermal gradients and the resulting stresses [13].

Guide 3: Mitigating Structural Instability in Harsh Environments

Problem: Performance degradation or physical deformation under combined stresses of temperature, vibration, and humidity.

Investigation & Diagnosis:

- Conduct Combined Environment Testing: Use ESS protocols that apply multiple stresses simultaneously, such as random vibration and temperature cycling [16] [17].

- Check for "Out-of-Family" Performance: Compare performance data with other units; results that deviate significantly from the production lot indicate an underlying instability [16].

Solution:

- Apply Environmental Stress Screening (ESS): Implement ESS on 100% of production or repaired units to force latent defects to fail before delivery [16].

- Enhance Mechanical Design: Improve structural support and use damping materials to mitigate vibration. Incorporate protective coatings or seals to guard against humidity and corrosion [18].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Thermal Cycling Test per JEDEC JESD22-A104

- Objective: To evaluate the ability of a component to withstand extreme temperature cycling.

- Methodology:

- Place the Unit Under Test (UUT) in a thermal chamber.

- Cycle the temperature between a defined low (e.g., -65°C) and high (e.g., +125°C) extreme.

- Maintain the temperature at each extreme for a specified dwell time (e.g., 10-15 minutes).

- Use a transition rate of approximately 10°C per minute between extremes.

- Perform interim functional tests at set intervals (e.g., every 100 cycles) and a final functional test upon completion [15].

- Failure Criteria: Any electrical failure, visible crack, or delamination detected during inspection.

Protocol 2: Thermal Shock Test per IPC-TM-650 Method 2.6.7

- Objective: To determine the resistance of a part to sudden, severe temperature changes.

- Methodology:

- Use a dual-chamber system with one chamber set to a cold extreme (e.g., -55°C) and the other to a hot extreme (e.g., +150°C).

- Transfer the UUT between chambers rapidly, with a transfer time of less than 15 seconds to achieve the required shock.

- Expose the UUT to each temperature for a dwell time sufficient to stabilize.

- Repeat the cycle for a specified number of times [14] [15].

- Perform a thorough visual and functional inspection after testing.

- Failure Criteria: Cracking of PTHs, barrel cracks, or separation of material layers identified via microsectioning [15].

Quantitative Data for Common Materials

Table 1: Coefficients of Linear Thermal Expansion for Common Engineering Materials [13]

| Material | Coefficient of Linear Thermal Expansion (α) °F⁻¹ |

|---|---|

| Carbon Steel | 5.8 × 10⁻⁶ |

| Stainless Steel | 9.6 × 10⁻⁶ |

| Aluminum | 13.3 × 10⁻⁶ |

| Copper | 9.3 × 10⁻⁶ |

| Lead | 16.3 × 10⁻⁶ |

Table 2: Key Industry Standards for Environmental Stress Testing

| Standard | Title / Scope | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| MIL-STD-810H | Environmental Test Methods and Engineering Guidelines | Aerospace and defense systems; general hardware qualification [17] |

| JEDEC JESD22-A104 | Temperature Cycling | Semiconductor packages and PCBs [15] |

| IPC-TM-650 2.6.7 | Thermal Shock | Printed board reliability, especially for PTHs [15] |

| DO-160G | Environmental Conditions and Test Procedures for Airborne Equipment | Avionics hardware testing for commercial and military aircraft [17] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Thermal and Environmental Stress Research

| Item | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Tg FR-4 Substrate | A printed circuit board laminate with a high glass transition temperature (Tg >170°C). It provides greater resistance to deformation at elevated temperatures compared to standard FR-4, reducing delamination risk [15]. |

| SAC305 Solder | A common lead-free solder alloy (96.5% Sn, 3.0% Ag, 0.5% Cu). Its fatigue resistance under thermal cycling is a key parameter studied for joint reliability in electronics [15]. |

| Ceramic Substrate | Used for high-temperature and high-power applications due to its low CTE (e.g., ~7 ppm/°C), which minimizes stress when paired with semiconductor dies [15]. |

| Ionic Liquids | Special salts that are liquid at room temperature. In research, they are investigated as green solvents to replace harsh, volatile solvents in chemical processes, improving safety and reducing environmental stress [19]. |

| Biodegradable Polymers | Engineered plastics designed to break down naturally. Their development is crucial for reducing long-term environmental waste, and studying their degradation under various environmental stresses is a key research area [19]. |

| Perovskite Crystals | A class of materials being intensively researched for next-generation solar panels. A major research focus is on improving their stability and longevity when exposed to environmental factors like heat, moisture, and light [19]. |

Workflow and Logic Diagrams

Thermal Stress Test Workflow

Troubleshooting Stress Failures

Bridging the Scale Gap: AI, Hybrid Models, and Computational Tools

Hybrid Mechanistic Modeling and Deep Transfer Learning for Cross-Scale Prediction

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Data Discrepancies Across Scales

Problem: A model trained on detailed laboratory-scale molecular data fails to predict pilot-scale product distributions accurately. The target domain (pilot plant) only provides bulk property measurements, creating a data type mismatch [20].

Solution: Implement a Property-Informed Transfer Learning strategy.

- Integrate Bulk Property Equations: Incorporate mechanistic equations for calculating bulk properties directly into the neural network architecture. This creates a bridge between molecular-level predictions and available pilot-scale data [20].

- Fine-Tune with Limited Data: Use the limited pilot-scale bulk property data to fine-tune only the relevant parts of the pre-trained model. This adapts the model to the new scale without requiring extensive new molecular-level data [20].

Preventive Measures:

- Plan data collection at different scales early in the project, ensuring alignment between measured variables where possible.

- Design the initial laboratory-scale data-driven model with future integration of bulk property calculations in mind.

Guide 2: Optimizing Transfer Learning Network Architecture

Problem: Poor performance after transferring a laboratory-scale model to a pilot-scale application. The standard trial-and-error approach for deciding which network parameters to freeze or fine-tune is inefficient and ineffective [20].

Solution: Adopt a structured deep transfer learning network architecture that mirrors the mechanistic model's logic.

- Deconstruct the Model Logic: Design the network with separate modules to handle different inputs, similar to a mechanistic model. For instance, use a

Process-based ResMLPfor process conditions and aMolecule-based ResMLPfor feedstock composition [20]. - Selective Fine-Tuning: Based on the scale-up scenario, fine-tune only the affected modules.

Preventive Measures:

- Document the source domain (lab-scale) model's architecture and training parameters thoroughly.

- Perform an ablation study during the initial model development to understand the contribution of different network modules.

Guide 3: Ensuring Model Interpretability and Fairness in Clinical Applications

Problem: A transferred learning model for clinical prognosis, such as Ischemic Heart Disease (IHD) prediction, provides accurate results but lacks explainability, raising concerns about clinical adoption and potential demographic bias [21].

Solution: Integrate Explainable AI (XAI) and fairness-aware strategies into the transfer learning pipeline.

- Implement SHAP Analysis: Use SHapley Additive exPlanations (SHAP) to quantify the contribution of each input feature (e.g., clinical marker) to the final prediction, providing transparency for clinicians [21].

- Apply Demographic Reweighting: During the model training or fine-tuning phase, apply a reweighting strategy to the training data to minimize performance disparities across different demographic subgroups (e.g., based on age or gender) [21].

Preventive Measures:

- Select source domain data for pre-training that is as demographically diverse as possible.

- Build interpretability and fairness metrics into the initial model validation protocol, not as an afterthought.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the core principle behind using hybrid modeling for scale-up? A1: Hybrid modeling separates the problem: a mechanistic model describes the intrinsic, scale-independent reaction mechanisms, while a deep learning component, trained on data from the mechanistic model, automatically captures the hard-to-model transport phenomena that change with reactor scale. This combines physical knowledge with data-driven flexibility [20].

Q2: Why is transfer learning particularly suited for cross-scale prediction in chemical processes? A2: During scale-up, the apparent reaction rates change due to variations in transport phenomena, but the underlying intrinsic reaction mechanisms remain constant. Transfer learning leverages this by transferring knowledge of the fundamental mechanism (from the source domain) and only fine-tunes the model to adapt to the new flow and transport regime of the target scale, reducing data and computational costs [20].

Q3: My pilot-scale data is very limited. Can transfer learning still be effective? A3: Yes. The primary advantage of transfer learning in this context is its ability to achieve high performance in the target domain (pilot scale) with minimal data by leveraging knowledge gained from the data-rich source domain (laboratory scale) [20].

Q4: How can I ensure my model's predictions are trusted by process engineers or clinicians? A4: For chemical processes, using a network architecture that reflects the structure of the mechanistic model builds inherent trust. For clinical applications, integrating explainable AI (XAI) tools like SHAP provides clear, quantifiable reasoning for each prediction, highlighting the most influential clinical features [20] [21].

Q5: What are the common pitfalls when fine-tuning a model for a new scale? A5: The two most common pitfalls are:

- Over-fitting: This occurs when using a small target-scale dataset and over-optimizing the model on it. Mitigate this by using data augmentation and selectively freezing parts of the network [20].

- Catastrophic Forgetting: The model forgets the general knowledge learned from the source domain. This is addressed by using a well-designed network architecture that allows for targeted fine-tuning of specific modules [20].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Developing a Molecular-Level Kinetic Model for Naphtha FCC

This protocol forms the foundation for generating the source domain data [20].

Objective: To develop a high-precision molecular-level kinetic model from laboratory-scale experimental data.

Methodology:

- Feedstock Characterization: Use analytical techniques (e.g., GC-MS) to determine the detailed molecular composition of the naphtha feedstock.

- Laboratory-Scale Experiments: Conduct experiments in a laboratory-scale reactor (e.g., fixed fluidized bed) under a wide range of controlled conditions (temperature, pressure, catalyst-to-oil ratio).

- Product Analysis: Analyze the product stream to obtain a detailed molecular-level distribution of outputs.

- Reaction Network Generation: Use a framework like the Structural Unit and Bond-Electron Matrix (SU-BEM) to generate a comprehensive reaction network [20].

- Parameter Estimation: Regress the kinetic parameters from the experimental data to complete the mechanistic model.

Protocol 2: Implementing Hybrid Transfer Learning for Scale-Up

This protocol details the transfer of knowledge from laboratory to pilot scale [20].

Objective: To adapt a laboratory-scale data-driven model to accurately predict pilot-scale product distributions.

Methodology:

- Source Model Training:

- Inputs: Process conditions and feedstock molecular composition from the laboratory-scale kinetic model.

- Outputs: Product molecular composition.

- Architecture: A neural network with separate ResMLPs for process conditions and molecular composition, feeding into an integrated ResMLP [20].

- Training Data: A large dataset generated by running the validated molecular-level kinetic model.

- Model Adaptation:

- Data Augmentation: Expand the limited pilot-scale dataset through augmentation techniques.

- Network Modification: Incorporate bulk property calculation equations into the output layer of the pre-trained network.

- Selective Fine-Tuning: Freeze the

Molecule-based ResMLPand fine-tune theProcess-basedandIntegrated ResMLPsusing the augmented pilot-scale data and bulk property targets [20].

- Validation: Compare model predictions against held-out pilot-scale experimental data.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Key Performance Metrics from Cross-Scale Learning Applications

This table summarizes quantitative outcomes from implementing hybrid and transfer learning models in different domains.

| Field of Application | Model / Architecture | Key Performance Metric | Result | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Engineering (Naphtha FCC) | Hybrid Mechanistic + Transfer Learning | Prediction of pilot-scale product distribution | Achieved with minimal pilot-scale data | [20] |

| Healthcare (IHD Prognosis) | X-TLRABiLSTM (Explainable Transfer Learning) | Classification Accuracy | 98.2% | [21] |

| Healthcare (IHD Prognosis) | X-TLRABiLSTM (Explainable Transfer Learning) | F1-Score | 98.1% | [21] |

| Healthcare (IHD Prognosis) | X-TLRABiLSTM (Explainable Transfer Learning) | Area Under the Curve (AUC) | 99.1% | [21] |

| Healthcare (IHD Prognosis) | X-TLRABiLSTM (with Fairness Reweighting) | Max F1-Score Gap (Demographic Fairness) | ≤ 0.6% | [21] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular-Level Modeling

This table lists key computational tools and frameworks used in advanced molecular engineering and scale-up research.

| Item Name | Function / Purpose | Specific Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular-Level Kinetic Modeling Framework | Describes complex reaction systems at the molecular level to generate high-precision training data. | Structure-Oriented Lumping (SOL), Molecular Type and Homologous Series (MTHS), Structural Unit and Bond-Electron Matrix (SU-BEM) [20] |

| Neural Network Potential (NNP) | Runs molecular simulations millions of times faster than quantum-mechanics-based methods while matching accuracy. | Egret-1, AIMNet2 (available on platforms like Rowan) [22] |

| Physics-Informed Machine Learning Model | Predicts molecular properties (e.g., pKa, solubility) by combining physical models with data-driven learning. | Starling (for pKa prediction, available on platforms like Rowan) [22] |

| Residual Multi-Layer Perceptron (ResMLP) | A core building block in deep learning architectures designed for complex reaction systems, helping to overcome training difficulties in deep networks. | Used to create separate network modules for process conditions and molecular features [20] |

| Explainable AI (XAI) Toolbox | Provides post-hoc interpretability for model predictions, crucial for clinical and high-stakes applications. | SHAP (SHapley Additive exPlanations) [21] |

Workflow Visualizations

Cross-Scale Model Architecture

Selective Fine-Tuning Logic

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key differences between GNNs and Transformers for molecular property prediction?

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) and Transformers represent two powerful but architecturally distinct approaches for molecular machine learning. GNNs natively operate on the graph structure of a molecule, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. They learn representations by passing messages between connected nodes, effectively capturing local topological environments. [23] [24] Transformers, adapted for molecular data, often rely on a linearized representation of the molecule (like a SMILES string) or can be integrated into graph structures (Graph Transformers) to leverage self-attention mechanisms. This allows them to weigh the importance of different atoms or bonds regardless of their proximity, potentially capturing long-range interactions within the molecule more effectively. [25]

Q2: My model performs well on the QM9 dataset but poorly on my proprietary compounds. What could be wrong?

This is a classic issue of dataset shift or out-of-distribution (OOD) generalization. The QM9 dataset contains 134,000 small organic molecules made up of carbon (C), hydrogen (H), oxygen (O), nitrogen (N), and fluorine (F) atoms. [26] If your proprietary compounds contain different atom types, functional groups, or are significantly larger in size, the model may fail to generalize. To troubleshoot:

- Check Data Similarity: Analyze the distribution of key molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, polarity) between QM9 and your dataset.

- Use OOD Splits: During development, benchmark your model's performance on OOD splits, such as splitting by molecular scaffolds, to better simulate real-world performance. [25] [27]

- Transfer Learning: Consider pre-training your model on a larger, more diverse chemical dataset before fine-tuning it on your specific data.

Q3: How can I handle the variable size and structure of molecular graphs in a GNN?

GNNs are inherently designed to handle variable-sized graphs. The key is the use of a readout layer (or global pooling layer) that aggregates the learned node features into a fixed-size graph-level representation. Common methods include:

- Global Mean Pooling: Takes the element-wise mean of all node features in the graph. This is simple and often effective. [26]

- Global Sum Pooling: Takes the element-wise sum of all node features.

- Global Max Pooling: Takes the element-wise maximum of all node features. This fixed-size graph-level vector is then passed to fully connected layers for the final property prediction. [26]

Q4: What are some common data preprocessing steps for molecular graphs?

Proper featurization is critical for model performance. Standard preprocessing includes:

- Atom Featurization: Encoding atom properties such as element symbol, number of valence electrons, number of hydrogen bonds, and hybridization state into a numerical vector. [23]

- Bond Featurization: Encoding bond properties such as bond type (single, double, triple, aromatic) and whether it is conjugated. [23]

- Graph Generation: Using tools like RDKit to convert SMILES strings into molecule objects, from which atom features, bond features, and connectivity information (pair indices) can be extracted. [23]

Q5: Why is my graph transformer model overfitting on the small BBBP dataset?

The BBBP dataset is relatively small (2,050 molecules), [23] [25] and transformer models, with their large number of parameters, are prone to overfitting. You can mitigate this by:

- Increasing Regularization: Apply aggressive dropout and weight decay.

- Using Simplified Architectures: As demonstrated in recent research, a standard self-attention mechanism coupled with a GPS Transformer framework can be effective and more efficient in low-data regimes. [25]

- Data Augmentation: Artificially expand your training set using techniques like SMILES randomization or adding noise to molecular coordinates.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Model Performance is Poor or Stagnant

Checklist:

- Data Quality and Splitting: Ensure your data is correctly featurized and that you are using a scaffold split to avoid data leakage and get a realistic performance estimate, especially for the BBBP dataset. [25]

- Model Capacity: Your model might be too simple or too complex. For smaller datasets like BBBP, a simpler GCN or a specifically designed transformer for low-data regimes is advisable. [26] [25] For larger datasets like QM9, you can use deeper architectures.

- Hyperparameter Tuning: Systematically tune key hyperparameters such as learning rate, hidden layer dimensions, number of layers, and dropout rate. The table below summarizes architectures from successful implementations.

Table 1: Representative Model Architectures and Performance

| Model | Dataset | Architecture Details | Key Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| MPNN [23] | BBBP (2,050 molecules) | Message-passing steps followed by readout and fully connected layers. | Implementation example for molecular property prediction. |

| GCN [26] | QM9 (130k+ molecules) | 3 GCN layers (128 channels), global mean pool, 2 linear layers (64, 1 unit). | Test MAE: 0.74 (on normalized target). |

| GPS Transformer [25] | BBBP (2,050 molecules) | Graph Transformer with Self-Attention, designed for low-data regimes. | State-of-the-art ROC-AUC: 78.8%. |

Problem: Long Training Times or Memory Issues

Checklist:

- Batch Size: Reduce the batch size. This is the most direct way to lower GPU memory usage.

- Model Simplification: Reduce the number of hidden units or GNN/transformer layers.

- Graph Size: If your molecules are very large (many atoms), consider techniques to sample subgraphs or use pooling layers to coarsen the graph structure during training.

- Mixed Precision: Use mixed-precision training (e.g., using tf.float16 or torch.float16) to speed up training and reduce memory footprint.

Problem: Inability to Reproduce Published Results

Checklist:

- Data Preprocessing: Verify that you are using the exact same data split (train/validation/test) and preprocessing steps (featurization, normalization) as the original paper.

- Code and Libraries: Ensure you are using the same library versions. Differences in deep learning frameworks or graph neural network libraries can lead to varying results.

- Random Seeds: Set random seeds for all random number generators (Python, NumPy, TensorFlow/PyTorch) to ensure reproducible parameter initialization and data shuffling. [23]

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing a GNN for Molecular Property Prediction (e.g., on QM9)

This protocol outlines the steps to train a Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) on the QM9 dataset, following a standard practice. [26]

Dataset Loading & Preprocessing:

- Load the QM9 dataset using a library like

torch_geometric. - The dataset contains 130,831 molecules. Each node has 11 atomic features.

- Shuffle the dataset with a fixed random seed (e.g., 42) for reproducibility.

- Split the data into training (110,831 graphs), validation (10,000), and test (10,000) sets.

- Normalize the target property using the mean and standard deviation computed from the training set.

- Load the QM9 dataset using a library like

Model Definition:

- Architecture:

GraphClassificationModel[26]- Input Layer: Accepts node features (dimension=11).

- GCN Layers: Three consecutive GCN layers with ReLU activation, transforming node features to 128 dimensions.

- Readout Layer: A global mean pooling layer to create a fixed-size graph representation (128 dimensions).

- Classifier: Two fully connected (linear) layers. The first reduces the dimension from 128 to 64 (with ReLU and Dropout), and the second outputs the final prediction.

- See the GCN Forward Pass diagram below.

- Architecture:

Training Configuration:

- Loss Function: Mean Squared Error (MSE) for regression.

- Optimizer: Adam.

- Evaluation Metric: Mean Absolute Error (MAE) on the test set.

Diagram 1: GCN Forward Pass

Protocol 2: Training a Transformer for BBBP Permeability Prediction

This protocol describes how to achieve state-of-the-art results on the BBBP dataset using a transformer architecture. [25]

Dataset:

Model Definition - GPS Transformer:

- The model is based on the General, Powerful, Scalable (GPS) Graph Transformer framework. [25]

- The key innovation is the integration of a standard Self-Attention mechanism within the GPS framework, which has been shown to perform exceptionally well in this low-data regime.

- The model processes local structural information through a GNN-like component and global interactions through the self-attention mechanism.

Training and Evaluation:

- The primary evaluation metric for this binary classification task is the Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve (ROC-AUC).

- The target is to achieve a ROC-AUC of 78.8% or higher, which represents the state-of-the-art for this dataset. [25]

Diagram 2: Graph Transformer Architecture

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Software and Data Resources for Molecular ML

| Item Name | Type | Function / Application | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [23] | Cheminformatics Library | Converts SMILES strings to molecular graphs; generates atomic and molecular features. | Open-source, widely used for feature generation and molecular manipulation. |

| MolGraph [24] | GNN Library | A Python package for building GNNs highly compatible with TensorFlow and Keras. | Simplifies the creation of GNN models for molecular property prediction. |

| PyTorch Geometric [26] | GNN Library | A library for deep learning on graphs, built upon PyTorch. | Provides many pre-implemented GNN layers and standard benchmark datasets (e.g., QM9). |

| QM9 Dataset [26] [27] | Benchmark Dataset | A comprehensive dataset of 134k small organic molecules for quantum chemistry. | Contains 19 regression targets; a standard benchmark for molecular property prediction. |

| BBBP Dataset [23] [25] | Benchmark Dataset | A smaller dataset for binary classification of blood-brain barrier permeability. | Contains 2,050 molecules; ideal for testing models in low-data regimes. |

| ColorBrewer [28] [29] | Visualization Tool | Provides colorblind-friendly color schemes for data visualization. | Ensures accessibility and clarity in charts and diagrams. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Workflow Setup

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between using Rosetta for de novo enzyme design versus for thermostability prediction?

Rosetta is used for two distinct major tasks in computational enzyme engineering, each with different protocols and underlying principles.

- De novo Enzyme Design: This process aims to create entirely new enzyme activity in a protein scaffold. The Rosetta

enzyme_designapplication is used to repack or redesign protein residues around a ligand or substrate. A critical component is the use of catalytic constraints—predefined geometric parameters (distances, angles, dihedrals) between catalytic residues and the substrate that penalize non-productive conformations. The protocol involves iterative cycles of sequence design and minimization with these constraints to create a functional active site [30] [31]. - Thermostability Prediction: This task focuses on improving the stability of an existing enzyme. Modern approaches use Rosetta Relax or ddG applications on an ensemble of protein conformations (e.g., generated from AlphaFold models) rather than a single static structure. This accounts for protein flexibility and eliminates "scaffold bias," leading to more accurate predictions of changes in the free energy of unfolding (ΔΔG) upon mutation [32].

Q2: How do I choose between a cluster model and a QM/MM approach for studying my enzyme's reaction mechanism?

The choice depends on the scientific question and available computational resources. The table below summarizes the key differences.

Table: Comparison of QM Cluster and QM/MM Models for Reaction Mechanism Studies

| Feature | QM Cluster Model | QM/MM Model |

|---|---|---|

| System Size | Small, chemically active region (a few hundred atoms) [33]. | Full enzyme structure [33]. |

| Methodology | Truncates the active site; uses DFT, MP2, or DFTB methods [33]. | Partitions system into a QM region (active site) and an MM region (protein environment) [33]. |

| Advantages | Computationally efficient; easier to set up and run [33]. | More realistic; accounts for full protein electrostatic and steric effects [33]. |

| Disadvantages | Neglects effects of the protein environment and long-range electrostatics [33]. | Higher computational cost; requires handling of QM-MM boundary [33]. |

| Ideal Use Case | Initial, rapid scanning of possible reaction pathways or transition state geometries [33]. | Detailed study of mechanism within the native protein environment, including the role of second-shell residues [33]. |

Q3: Why is my designed enzyme stable in simulations but inactive in the lab?

This common issue in scaling molecular engineering processes often stems from limitations in conformational sampling or the energy function.

- Insufficient Conformational Sampling: Short MD simulations (nanoseconds to microseconds) may not capture large-scale conformational changes or rare events crucial for function, such as substrate access or product release [33]. Enhanced sampling techniques may be required.

- Static vs. Dynamic Design: Traditional Rosetta design often uses a single, static backbone conformation. A more robust approach involves designing against ensembles of conformations generated by MD simulations or AlphaFold, which can capture native state flexibility and lead to designs that are functional across multiple states [32].

- Over-reliance on Energetics: The Rosetta energy function is classical and may not perfectly capture quantum mechanical effects essential for catalysis. While catalytic constraints guide geometry, they may not fully represent the electronic environment. Supplementing Rosetta with QM/MM simulations can provide a more complete picture [33] [34].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Rosetta Enzyme Design Produces Unstable Variants

This problem occurs when the drive to enhance catalytic activity compromises the structural integrity of the protein scaffold.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Identify Destabilizing Mutations:

- Action: Use the

Rosetta ddg_monomerapplication or the more advanced ensemble-based Relax protocol to calculate the ΔΔG of folding for your designed variants [32]. - Interpretation: A positive ΔΔG value indicates a destabilizing mutation. Focus on variants with predicted ΔΔG < 0 (stabilizing) or minimally destabilizing.

- Action: Use the

Employ FuncLib for Smart Library Design:

- Action: Instead of random mutagenesis, use the FuncLib server. This computational methodology combines Rosetta design with phylogenetic analysis to predict highly stable and functional multi-mutant variants. It ranks sequences based on predicted stability, ensuring your experimental library is enriched with folded, stable proteins [34].

- Example: FuncLib was successfully used to design Kemp eliminase variants that showed both enhanced activity and increased denaturation temperatures, overcoming the classic activity-stability trade-off [34].

Validate with Ensemble-Based Stability Prediction:

- Protocol:

- Step 1: Generate an ensemble of conformations for your wild-type and designed enzyme using MD simulations or multiple AlphaFold models [32].

- Step 2: Run the Rosetta

Relaxapplication on each model in the ensemble for both sequences [32]. - Step 3: Calculate the average Rosetta energy score across the entire ensemble for both the wild-type and the variant.

- Step 4: A significant increase in the average energy for the variant suggests destabilization, even if a single static structure appears stable [32].

- Protocol:

Problem: MD Simulations Show Poor Catalytic Residue Positioning

The active site geometry in simulations deviates from the theoretically ideal catalytic conformation, leading to poor activity.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Verify Force Field Parameters:

- Action: Ensure that the protonation states of all catalytic residues (e.g., Asp, Glu, His, Lys) are correct for the reaction being catalyzed. Use a tool like

H++orPROPKAbefore running the simulation. - Action: For non-standard residues or substrates, carefully generate accurate force field parameters using tools like

CGenFForACPYPE.

- Action: Ensure that the protonation states of all catalytic residues (e.g., Asp, Glu, His, Lys) are correct for the reaction being catalyzed. Use a tool like

Apply Restraints to Preserve Active Site Geometry:

- Action: In your MD simulation input, apply soft harmonic or flat-bottomed restraints to the key atomic distances, angles, and dihedrals that define the catalytic mechanism. These should be based on your QM calculations or crystal structures of analogous enzymes.

- Rationale: This allows the rest of the protein to move dynamically while maintaining the crucial catalytic geometry [31].

Use QM/MM to Guide the Design:

- Action: If restraints are too artificial, run shorter QM/MM MD simulations. These simulations use a more accurate QM potential for the active site, allowing the enzyme to naturally find its optimal configuration for catalysis.

- Protocol:

- Step 1: Set up the system, partitioning it into QM (substrate, catalytic residues, cofactors) and MM (rest of protein, solvent) regions [33].

- Step 2: Run a QM/MM geometry optimization to relax the structure.

- Step 3: Perform a QM/MM MD simulation to sample configurations and identify stable, catalytically competent states [33].

- Diagram: The workflow for integrating computational methods to resolve active site issues is as follows:

Problem: Low Experimental Activity Despite High Predicted Activity

Your computational models suggest a highly active enzyme, but wet-lab assays show minimal turnover.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Check for Catalytic Constraints in Rosetta:

- Action: Ensure your

enzyme_designrun correctly included the catalytic constraints file (-enzdes::cstfile). Verify that theREMARK 666lines in your input PDB file correctly match the residues specified in the constraint file [31]. - Troubleshooting: Run a control design without constraints. If the results are similar, the constraints may not be applied correctly.

- Action: Ensure your

Investigate Substrate Access and Product Release:

- Action: Run long-timescale MD simulations (if feasible) starting from the product-bound state of your designed enzyme.

- What to look for: Observe if the product dissociates from the active site. A clogged or overly rigid active site can trap the product, preventing multiple turnover and leading to low observed activity. Analyze tunnels and channels using tools like

CAVER.

Identify and Eliminate Non-Productive Substrate Binding Poses:

- Action: Perform multiple replicates of MD simulations with the substrate docked in the active site.

- Example: In the engineering of a Kemp eliminase, molecular simulations revealed that the origin of catalytic enhancement in the best variant was the "progressive elimination of a catalytically inefficient substrate conformation" present in the original design [34]. Use simulation data to identify such non-productive poses and redesign the active site to disfavor them.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools and Resources for Enzyme Engineering

| Tool/Resource | Function | Key Application in Enzyme Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | A comprehensive platform for macromolecular modeling and design [30] [32] [31]. | enzyme_design: For de novo design and active site optimization [31]. Relax/ddG: For predicting mutational effects on stability [32]. FuncLib: For designing smart, stable mutant libraries [34]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER, NAMD) | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time [33]. | Sampling enzyme conformational dynamics. Studying substrate binding/release. Identifying non-productive poses and allosteric networks [33]. |

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) Software (e.g., Gaussian, ORCA) | Solves the Schrödinger equation to model electronic structure and chemical reactions [33]. | Calculating energy profiles of reaction pathways. Characterizing transition states. Providing parameters for catalytic constraints [33]. |

| Hybrid QM/MM Software | Combines QM accuracy for the active site with MM speed for the protein environment [33]. | Modeling bond breaking/formation in a realistic protein environment. Obtaining detailed, atomistic insight into catalytic mechanisms [33]. |

| AlphaFold2 | Protein structure prediction from amino acid sequence [32]. | Generating high-quality structural models for scaffolds lacking crystal structures. Creating initial models for MD or Rosetta [32]. |

| Catalytic Constraint (CST) File | A text file defining the ideal geometry for catalysis in Rosetta [31]. | Guiding Rosetta's design algorithm to create active sites with the correct geometry to stabilize the transition state [31]. |

Advanced Fermentation and Bioprocess Control for Microbial Biomanufacturing Scale-Up

FAQs: Addressing Common Scale-Up Challenges

FAQ 1: What are the most critical process parameters to monitor during fermentation scale-up, and why? The most critical process parameters to monitor are dissolved oxygen (DO), pH, temperature, and agitation rate [35]. During scale-up, factors like mixing time and mass transfer efficiency change significantly. For instance, mixing time can increase from seconds in a lab-scale bioreactor to several minutes in a commercial-scale vessel, leading to gradients in oxygen and nutrients [36]. Precise, real-time monitoring and control of these parameters are essential to maintain optimal conditions for microbial growth and product formation, ensuring batch-to-batch consistency [35].

FAQ 2: How can we mitigate contamination risks during pilot and production-scale fermentation? Mitigating contamination requires a multi-layered approach:

- Closed System Operations: Utilize features like sterile sampling ports, magnetically coupled agitators (to eliminate dynamic seals), and aseptic connectors to minimize human intervention and system openings [35].

- Robust Sterilization: Implement Steam-in-Place (SIP) sterilization protocols for the entire bioreactor and associated fluid paths [35].

- Raw Material Control: Carefully select and test animal-origin-free raw materials to prevent the introduction of adventitious agents [37].

- Process Control: Establish a comprehensive program that includes adventitious-agent testing of cell banks and monitoring of harvest materials [37].

FAQ 3: What advanced control strategies move beyond basic PID control for complex bioprocesses? For highly non-linear and complex bioprocesses, advanced control strategies offer significant advantages:

- Model Predictive Control (MPC): A multivariate control algorithm that uses a real-time process model to predict future states and optimize a cost function, improving steady-state response and predicting disturbances [38].

- Adaptive Control & Fuzzy Logic: These systems can handle imprecise domain knowledge and noisy data, imitating human decision-making to adapt to changing process conditions [38] [39].

- Artificial Neural Network (ANN)-based Control: ANNs are designed for pattern recognition, classification, and prediction, making them suitable for modeling complex bioprocess kinetics [38]. These strategies are often implemented within a Distributed Control System (DCS) framework, where they perform high-level optimization while PID controllers manage device-level actuation [39].