Optimizing Molecular Similarity Thresholds in QSAR: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing molecular similarity thresholds in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling.

Optimizing Molecular Similarity Thresholds in QSAR: From Foundational Principles to Advanced Applications in Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on optimizing molecular similarity thresholds in Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling. We explore the fundamental principles of molecular similarity, from traditional structural comparisons to advanced 3D-QSAR and machine learning approaches. The content covers practical methodologies for threshold determination, addresses common challenges like activity cliffs and data imbalance, and presents rigorous validation frameworks. By synthesizing current research and emerging trends, this resource offers actionable strategies for enhancing the predictive accuracy and reliability of QSAR models in biomedical research and clinical development.

Understanding Molecular Similarity: The Bedrock of Effective QSAR Modeling

Molecular similarity is a foundational concept in cheminformatics and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling. The core principle, often called the "similar property principle," states that structurally similar molecules are expected to have similar properties or biological activities [1]. However, the definition of "similar" is highly subjective and context-dependent. Relying solely on structural resemblance is often insufficient for robust predictions, leading to the "similarity paradox" where similar molecules exhibit unexpectedly different activities [2] [3]. This technical guide explores the multifaceted nature of molecular similarity and provides practical protocols for optimizing its application in QSAR research, focusing on the critical role of similarity thresholds.

FAQs & Troubleshooting Guides

FAQ 1: What defines molecular similarity beyond simple structural resemblance?

Structural (2D) similarity, often based on molecular graphs and fingerprints, is just one perspective. True molecular similarity for biological activity depends on the context of the interaction and can be defined by several higher-order characteristics [2] [1]:

- Shape Similarity (3D): The three-dimensional molecular shape is a key determinant for how a molecule fits into a biological target. Molecules with different 2D structures can share similar 3D shapes, leading to similar activities.

- Surface Physicochemical Similarity: Properties like electrostatic potential, hydrophobicity, and polarizability, projected onto the molecular surface, directly influence binding. Similar surface properties can enable different structures to interact with a target in functionally equivalent ways.

- Pharmacophore Similarity: This describes the essential 3D arrangement of functional features (e.g., hydrogen bond donors/acceptors, hydrophobic regions) required for biological activity. It is a high-level abstraction focused on interaction capacity rather than the underlying scaffold.

- Biological Similarity: Similarity can be defined based on shared biological profiles, such as gene expression responses or other phenotypic readouts from high-throughput screening (HTS) [2].

FAQ 2: Why is optimizing the similarity threshold critical in QSAR and virtual screening?

The similarity threshold is a cutoff used to decide whether two molecules are sufficiently similar to infer similar properties. Optimizing this threshold is crucial for balancing prediction reliability and the identification of true positives [4].

- Too Low a Threshold: Includes too many dissimilar compounds, increasing background noise and the rate of false positives. This reduces the confidence in predictions.

- Too High a Threshold: Imposes too strict a requirement, potentially filtering out valid active compounds (false negatives) and limiting the exploration of novel chemical space, such as in scaffold hopping [5]. Research shows that the distribution of effective similarity scores is fingerprint-dependent, and applying an optimized, fingerprint-specific threshold can significantly enhance the confidence of predictions in tasks like target fishing [4].

Troubleshooting Guide 1: Addressing the "Similarity Paradox" and Activity Cliffs

Problem: Your QSAR model performs well on validation but fails to predict certain compounds accurately, even though they are structurally similar to compounds in the training set. This may be due to the "similarity paradox" or "activity cliffs," where small structural changes lead to large activity differences [2] [3].

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Large prediction errors for a subset of seemingly similar compounds. | Presence of activity cliffs; the model cannot capture critical local interactions. | Integrate matched molecular pair analysis (MMPA) to identify specific substitutions that cause drastic activity changes [3]. |

| Model is robust in cross-validation but poor in external prediction. | Experimental errors in the modeling set are misleading the model. The dataset may contain problematic structural or activity data [6]. | Use consensus QSAR predictions to flag compounds with large prediction errors for manual verification. Perform rigorous data curation [6]. |

| Inability to predict activity for a new scaffold. | The model's applicability domain (AD) is too narrow, failing to generalize. The new scaffold is outside the chemical space of the training set. | Use a read-across structure-activity relationship (RASAR) approach. This method augments traditional descriptors with similarity and error-based metrics from read-across, often improving external predictivity [2]. |

Troubleshooting Guide 2: Poor Performance in Similarity-Based Virtual Screening

Problem: Your similarity search for a target of interest returns too many false positives or fails to find active compounds with novel scaffolds.

| Symptom | Possible Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High hit rate but low confirmation rate in assays (many false positives). | The similarity threshold is set too low, allowing too many dissimilar compounds to pass. | Systematically optimize the similarity threshold for your specific fingerprint and target. Use a reference dataset to find the threshold that maximizes precision [4]. |

| Failure to identify active compounds with different core structures (scaffold hops). | Over-reliance on 2D structural fingerprints that cannot recognize shared 3D features or pharmacophores. | Switch to or combine with 3D similarity methods (shape, pharmacophore) or modern AI-driven representations (e.g., graph neural networks) that can learn complex structure-activity relationships [5]. |

| Inconsistent results when using different fingerprint types. | Each fingerprint captures different aspects of molecular structure; no single representation is universally best. | Use an ensemble approach. Combine the results from multiple fingerprint types (e.g., ECFP, AtomPair, MACCS) and different similarity metrics to get a more consensus and reliable prediction [4]. |

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Determining the Optimal Similarity Threshold for a QSAR/Target Fishing Model

This protocol outlines a systematic approach to find a fingerprint-specific similarity threshold that maximizes the confidence in predictions [4].

1. Objective: To establish a quantitative similarity threshold that effectively filters out background noise and maximizes the identification of true positive associations for a given molecular representation.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- High-Quality Reference Library: A curated database of known ligand-target interactions (e.g., from ChEMBL or BindingDB) with strong bioactivity (e.g., IC50, Ki < 1 μM) [4].

- Fingerprint Calculation Software: RDKit, PaDEL-Descriptor, or other cheminformatics toolkits.

- Computational Environment: Python/R environment with libraries for data analysis and machine learning.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Data Preparation. Prepare a benchmark dataset from your reference library. Ensure it contains known true positives (active compounds for a target) and true negatives (inactive or random compounds).

- Step 2: Molecular Representation. Calculate multiple types of 2D fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4, AtomPair, MACCS, RDKit) for all compounds in your dataset [4].

- Step 3: Similarity Calculation. For each query molecule, compute the pairwise Tanimoto similarity to all reference ligands in the library. The Tanimoto coefficient is calculated as: ( sim(x,y) = \frac{fp(x) \cdot fp(y)}{||fp(x)||^2 + ||fp(y)||^2 - fp(x) \cdot fp(y)} ) where ( fp(x) ) and ( fp(y) ) are the fingerprint vectors of two molecules [7].

- Step 4: Performance Evaluation. Conduct a leave-one-out cross-validation. For each query, retrieve the top-k most similar reference ligands and check if they are associated with the correct target. Measure performance using metrics like Precision, Recall, and ROC AUC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic curve) [6] [4].

- Step 5: Threshold Determination. Plot the Precision and Recall values against a range of possible similarity thresholds (e.g., from 0.1 to 0.9). The optimal threshold is often chosen at the point where Precision and Recall are balanced, for instance, by maximizing the F1-score. This threshold is fingerprint-specific [4].

4. Expected Output: A set of validated similarity thresholds, one for each fingerprint type, that can be applied to future virtual screening or QSAR studies to enhance prediction confidence.

Protocol 2: Workflow for Integrating Multiple Similarity Contexts in a RASAR Model

This protocol describes how to integrate various similarity concepts into a Read-Across Structure-Activity Relationship (q-RASAR) model, which enhances traditional QSAR [2].

1. Objective: To develop a predictive q-RASAR model that combines structural, physicochemical, and biological similarity descriptors to improve predictivity, especially for compounds near the applicability domain boundary.

2. Materials & Reagents:

- Endpoint Data: A curated dataset with biological activity/toxicity values.

- Descriptor Software: Tools like Dragon, PaDEL-Descriptor, or RDKit to calculate traditional molecular descriptors.

- Similarity Calculation Tools: Custom scripts to compute similarity matrices.

3. Methodology:

- Step 1: Calculate Traditional Descriptors. Generate a set of standard 1D, 2D, and 3D molecular descriptors for all compounds in the dataset.

- Step 2: Calculate Similarity Descriptors.

- Structural Similarity: Compute the maximum Tanimoto similarity for each compound to all other compounds in the training set using a fingerprint like ECFP4.

- Property Similarity: Calculate similarity based on key physicochemical properties (e.g., LogP, molecular weight).

- Error-based Descriptors: Include descriptors that capture the prediction error of a preliminary baseline QSAR model for the nearest neighbors [2].

- Step 3: Descriptor Fusion. Amalgamate the traditional descriptors and the new similarity/error-based descriptors into a single, comprehensive descriptor pool for the RASAR model.

- Step 4: Model Building and Validation. Split the data into training and test sets. Use a machine learning algorithm (e.g., Random Forest, PLS) to build a model on the training data. Critically validate the model using both internal cross-validation and external validation on the held-out test set. The applicability domain should be defined.

4. Expected Output: A validated q-RASAR model with (hopefully) superior external predictivity compared to a standard QSAR model, achieved by leveraging multiple facets of molecular similarity.

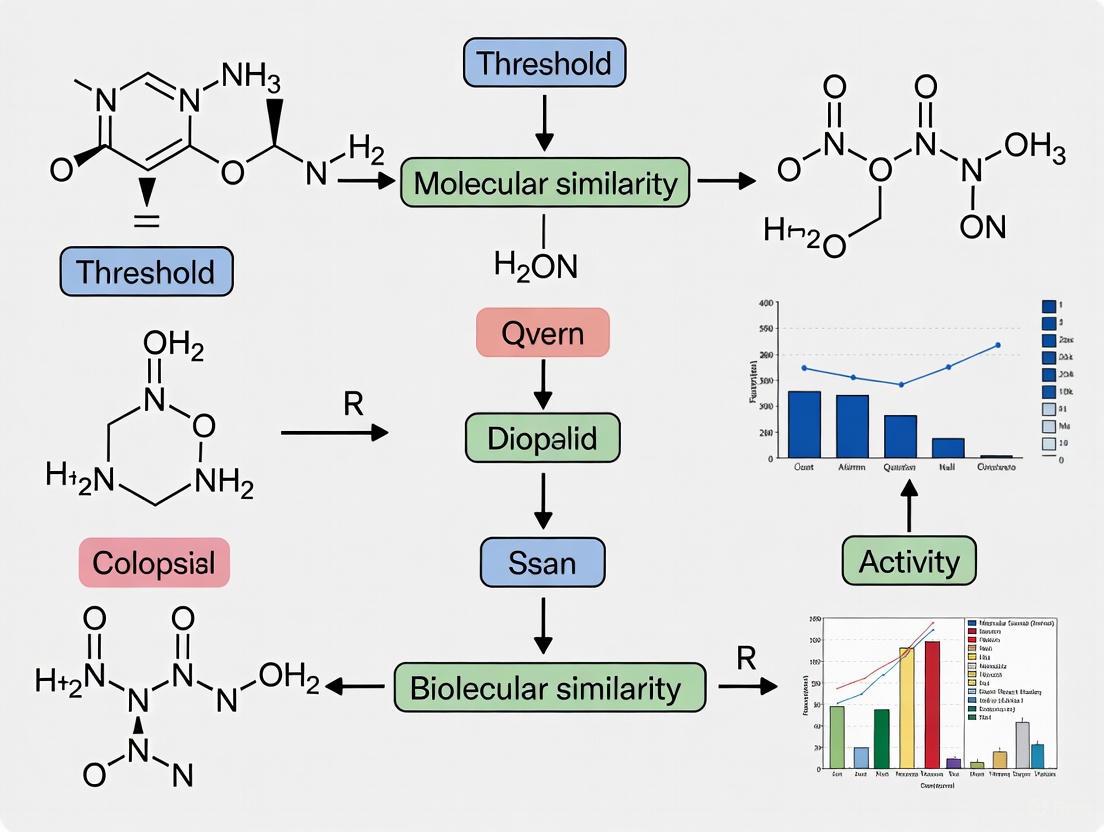

Visualization of Workflows

Diagram 1: Molecular Similarity Threshold Optimization

Diagram 2: q-RASAR Model Development Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Similarity Studies

| Item Name | Function/Application | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit (Open-Source Cheminformatics) | Calculates molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and performs structural standardization. | Core toolkit for prototyping; supports ECFP, AtomPair, and other key fingerprints [4]. |

| Dragon / PaDEL-Descriptor | Commercial (Dragon) and open-source (PaDEL) software for calculating thousands of molecular descriptors. | Essential for generating a comprehensive pool of descriptors for traditional QSAR and RASAR models [8]. |

| ChEMBL / BindingDB | Publicly accessible, curated databases of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. | Source for building high-quality reference libraries for target fishing and model training [4]. |

| Tanimoto Coefficient | A standard metric for calculating the similarity between two molecular fingerprints. | The most widely used similarity metric for 2D fingerprints; values range from 0 (no similarity) to 1 (identical) [7]. |

| ECFP4 (Extended-Connectivity Fingerprint) | A circular topological fingerprint that captures molecular features at a diameter of 4 bonds. | A widely used and generally effective fingerprint for similarity searching and as a descriptor in QSAR models [5]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | A deep learning model that operates directly on molecular graph structures. | A modern AI-driven representation that can capture complex structure-activity relationships beyond the capacity of predefined fingerprints [5]. |

FAQs: Troubleshooting Chemical Descriptor Applications

FAQ 1: How do I choose the right molecular fingerprint for my QSAR study?

Selecting the appropriate fingerprint is critical and depends on your specific dataset and the properties you wish to predict. Different fingerprints capture fundamentally different aspects of the chemical space, leading to substantial differences in pairwise similarity and model performance [9]. Below is a structured guide to aid your selection.

Table: A Guide to Selecting Molecular Fingerprints for QSAR

| Fingerprint Category | Key Principle | Best Use Cases | Common Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Circular Fingerprints | Dynamically generates circular atom neighborhoods from a molecular graph. Excellent at capturing local structural features [10]. | Generally a strong, default choice for drug-like compounds and complex structures like Natural Products (NPs) [9] [11]. | ECFP, ECFP6, FCFP [12] [9] |

| Path-Based Fingerprints | Indexes all linear paths through the molecular graph up to a given length [9]. | A robust and widely used option for general-purpose QSAR modeling. | FP2, Daylight [12] [10] |

| Substructure-Based (Structural Keys) | Uses a predefined dictionary of functional groups and substructural motifs [9] [10]. | Rapid filtering and searching for known pharmacophores. Good for interpretability. | MACCS, PubChem Fingerprints [12] [9] |

| Pharmacophore Fingerprints | Encodes atoms based on their role in molecular interactions (e.g., hydrogen bond donor) rather than structural identity [9]. | Focusing on biological activity and ligand-receptor interactions when structure is less critical. | Pharmacophore Pairs (PH2), Triplets (PH3) [9] |

| Shape-Based Fingerprints | Compares molecules based on their 3D steric volume and morphological features [10]. | Identifying novel bioactive ligands that are structurally dissimilar but shape-similar to a known active compound. | ROCS, USR [13] [10] |

Recommendation: For a standard QSAR study, begin with a circular fingerprint (e.g., ECFP). If you are working with specialized molecules like natural products, which have high structural complexity, do not assume ECFP is best; benchmark multiple fingerprint types as other encodings may match or outperform them [9].

FAQ 2: My QSAR model is overfitting. How can I improve its generalizability?

Overfitting often occurs when the model is too complex for the amount of available data. Key strategies involve optimizing the model architecture, the molecular representation, and the training process.

- Simplify the Fingerprint: A shorter fingerprint length or a smaller radius for circular fingerprints reduces the number of features and can prevent the model from learning overly specific patterns from your training set. For example, one study found a significant positive correlation between the radius of circular fingerprints and their accuracy on a specific task, suggesting that a larger radius captures more features, which could lead to overfitting on smaller datasets [11].

- Use a Validation Set: During model training, use a separate validation set to monitor performance. The training should be halted when the error on the validation set begins to increase, even if the error on the training set continues to decrease. This technique, known as early stopping, is a standard practice to prevent overfitting [12].

- Increase Data Diversity: If possible, augment your training set with more structurally diverse compounds. This helps the model learn the underlying structure-activity relationship rather than memorizing the training examples.

FAQ 3: What is an appropriate similarity threshold for a virtual screening campaign?

The optimal Tanimoto similarity threshold is not universal; it is highly context-dependent and influenced by the fingerprint type and the chemical space being explored.

- Common Starting Point: A threshold of 0.4 - 0.6 is often used for many tasks with standard fingerprints like ECFP [7] [9]. For instance, a widely adopted benchmark for molecular optimization requires maintaining a structural similarity greater than 0.4 [7].

- Task-Dependent Adjustment:

- For scaffold hopping (finding actives with novel core structures), you may need to lower the threshold (e.g., 0.2 - 0.4) to capture more diverse chemotypes.

- For lead optimization, where the goal is to find close analogs of a potent lead compound, a higher threshold (e.g., 0.7 - 0.8) might be more appropriate.

- Empirical Determination: The most reliable method is to conduct a retrospective analysis. Use known active and inactive molecules from your project's history to determine which threshold provides the best enrichment of actives.

FAQ 4: How should I handle the comparison of complex natural products?

Natural products (NPs) present a unique challenge due to their large, complex scaffolds with multiple stereocenters and a high fraction of sp³-hybridized carbons [9] [11]. Standard fingerprints developed for drug-like compounds may not perform optimally.

- Benchmark Multiple Fingerprints: Do not rely on a single fingerprint. Systematically evaluate the performance of various fingerprint types (circular, path-based, etc.) on your specific NP dataset and bioactivity prediction task [9].

- Consider Specialized Methods: For modular natural products like nonribosomal peptides and polyketides, retrobiosynthetic alignment algorithms (e.g., GRAPE/GARLIC) that compare molecules based on their biosynthetic origins can outperform conventional 2D fingerprints [11].

- Leverage High-Contrast Fingerprints: Some studies suggest that for certain NP classes, fingerprints like Atom Pair (AP) and Pharmacophore Triplets (PH3) can provide a high degree of contrast and good performance in classification tasks [9].

Experimental Protocol: Developing a Fingerprint-Based QSAR Model

This protocol outlines the key steps for creating a robust QSAR model using a fingerprint-based Artificial Neural Network (FANN-QSAR), a method validated for predicting biological activities and identifying novel lead compounds [12].

1. Dataset Curation and Preparation

- Data Source: Collect a set of compounds with consistent experimental bioactivity data (e.g., IC₅₀, Kᵢ). The dataset should be as large and structurally diverse as possible.

- Standardization: Process all molecular structures to remove salts, neutralize charges, and generate canonical tautomers using a tool like the ChEMBL structure curation package or RDKit [9]. This ensures consistency in fingerprint generation.

- Data Division: Randomly split the dataset into three parts:

2. Molecular Fingerprint Generation

- Selection: Choose at least two or three different types of fingerprints from distinct categories (e.g., ECFP6, FP2, MACCS) to compare their performance [12] [9].

- Generation: Use cheminformatics software (e.g., RDKit, OpenBabel, ChemAxon) to compute the fingerprints for every compound in your dataset. Ensure you use consistent parameters (e.g., a radius of 3 for ECFP, 1024 bits length) across all molecules [12].

3. Model Training with a Neural Network

- Architecture: Implement a feed-forward neural network. The fingerprint bits serve as the input layer. A typical setup includes one or two hidden layers with a non-linear activation function (e.g., ReLU) and a single neuron in the output layer for regression (predicting pIC₅₀) [12].

- Training Process: Train the network using a backpropagation algorithm on the training set. After each training epoch (a full pass through the training data), evaluate the model on the validation set.

- Early Stopping: Monitor the validation error. Halt the training process when the validation error has not decreased for a pre-defined number of epochs (patience). This ensures the model does not overfit to the training data [12].

4. Model Validation and Application

- Final Evaluation: Use the held-out test set to assess the model's generalization ability. Report standard statistical metrics like R² and Root Mean Square Error (RMSE).

- Virtual Screening: The validated model can screen large chemical databases (e.g., NCI, ZINC). Input the fingerprint of each database compound to predict its bioactivity, then prioritize the top-ranked compounds for experimental testing [12].

The workflow for this protocol is summarized in the following diagram:

Diagram Title: FANN-QSAR Modeling Workflow

Table: Key Computational Tools for Descriptor-Based Research

| Tool / Resource Name | Function / Application | Key Features & Notes |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit for generating fingerprints, standardizing structures, and molecular modeling. | Supports ECFP, FCFP, Atom Pairs, topological torsion, and MACCS keys. The de facto standard for Python-based cheminformatics [9]. |

| OpenBabel | A chemical toolbox designed to speak many languages related to chemical data. | Used for converting file formats and generating fingerprints like FP2 and MACCS [12]. |

| ROCS (Rapid Overlay of Chemical Structures) | A shape-based similarity method for virtual screening. | Used for identifying novel bioactive ligands that are shape-similar to a query, even if structurally dissimilar [13] [10]. |

| MATLAB with Neural Network Toolbox | High-level technical computing language for building and training machine learning models like ANN. | Used in the development of the FANN-QSAR method for its robust neural network implementation [12]. |

| Python Scikit-Learn | A free machine learning library for Python. | Provides simple and efficient tools for data mining and data analysis, ideal for building QSAR models after generating fingerprints with RDKit. |

| COCONUT & CMNPD Databases | Extensive, curated databases of natural products (NPs). | Essential sources of NP structures for benchmarking fingerprints and building models on complex chemical space [9]. |

FAQs on the Similarity Principle & QSAR

Q: What is the similarity principle in chemistry? A: The similarity principle, often called the similar property principle, states that similar compounds are likely to have similar properties [14]. This is a foundational concept in cheminformatics and drug design, suggesting that making minor structural changes to a molecule should not drastically alter its biological activity [15].

Q: How is molecular similarity quantified in QSAR studies? A: Similarity is typically quantified by first converting molecular structures into numerical representations called molecular fingerprints, and then calculating a similarity coefficient between them [14] [15]. The most common metric is the Tanimoto coefficient, which measures the overlap of features between two fingerprint vectors, yielding a score between 0 (no similarity) and 1 (identical) [15].

Q: What is an 'activity cliff' and why is it problematic? A: An activity cliff is a key exception to the similarity principle, where structurally similar compounds exhibit large differences in biological potency [15]. These are challenging for QSAR models because they represent a stark discontinuity in the chemical space where the similar property principle breaks down [15].

Q: What are the main types of molecular fingerprints used? A: Fingerprints can be categorized by the structural features they encode. The table below summarizes common types [15]:

| Fingerprint Type | Core Concept | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|

| Path-Based | Encodes linear paths of atoms and bonds through the molecular graph. | Simple, computationally efficient, good for substructure matching [15]. |

| Circular | Encodes the local environment (substructures) around each atom up to a defined radius. | Excellent at separating active from inactive compounds with similar properties [15]. |

| Atom-Pair | Encodes pairs of atoms and the topological distance (number of bonds) between them. | Informative for medium-range structural features, suitable for rapid similarity comparisons [15]. |

Q: Is a Tanimoto score of 0.85 always indicative of similar activity? A: No. While a threshold of T > 0.85 (for Daylight fingerprints) has been commonly used to define similar structures, it is a misunderstanding that this always reflects similar bioactivity [14]. The significance of a similarity score is highly context-dependent and varies with the fingerprint type, target class, and the specific assay [15].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: High similarity scores but divergent biological activity (Activity Cliffs).

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| 2D Similarity Masking 3D Differences | 2D fingerprints may not capture critical conformational or stereochemical differences. | Calculate 3D similarity measures (e.g., 3D pharmacophore fingerprints) or perform molecular alignment and shape comparison [15]. |

| Over-reliance on a Single Fingerprint | Different fingerprints highlight different structural aspects. | Benchmark multiple fingerprint types against your specific dataset and biological endpoint to identify the most predictive one [15]. |

| Insufficient Chemical Space Analysis | The similarity may be local and not representative of the broader structure-activity relationship (SAR). | Use dimensionality reduction techniques (like PCA, t-SNE, or UMAP) to project compounds into a 2D chemical space and visually inspect clustering; this complements numerical scores [15]. |

Problem: Poor performance of a QSAR model built using similarity-based descriptors.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Check | Proposed Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Narrow Chemical Diversity in Training Set | The model has not learned a broad enough SAR. | Ensure the training set encompasses a wide variety of chemical structures and that the model's applicability domain is clearly defined [16]. |

| Inadequate Data Quality | The biological activity data used for training is noisy or inconsistent. | Curate the dataset rigorously, checking for experimental consistency and error [16]. |

| Limitations of the Mathematical Model | A simple linear model may be unable to capture complex, non-linear SAR. | Explore more complex machine learning or deep learning models that can handle non-linear relationships in the data [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Molecular Similarity Analysis

Protocol 1: Conducting a Similarity-Based Virtual Screen

This methodology is used to identify potentially active compounds in large databases by using a known active molecule as a query [14].

- Query Selection: Select a compound with confirmed, potent biological activity as your query structure.

- Fingerprint Generation: Convert the query structure and all database structures into a consistent molecular fingerprint representation (e.g., Daylight, ECFP).

- Similarity Calculation: For every compound in the database, calculate its similarity to the query compound using the Tanimoto coefficient.

T(A,B) = c / (a + b - c), where:cis the number of features common to both molecules A and B.aandbare the number of features in molecules A and B, respectively [15].

- Ranking & Selection: Rank the database compounds in descending order of their similarity score to the query. Select the top-ranked compounds for experimental testing.

The following diagram illustrates this virtual screening workflow:

Protocol 2: Benchmarking Fingerprint Performance

This protocol helps identify the best fingerprint type for a specific research question.

- Curate a Benchmark Dataset: Assemble a dataset of compounds with reliable biological activity data for a specific target. Ensure it contains both active and inactive molecules and, if possible, known activity cliffs [16].

- Generate Multiple Fingerprints: Represent each compound in the dataset using several different types of fingerprints (e.g., Path-based, Circular, Atom-Pair) [15].

- Establish Similarity-Activity Relationships: For each fingerprint type, calculate the pairwise similarity matrix for all compounds. Analyze how well similarity scores correlate with similar activity.

- Evaluate Performance: Use metrics like Enrichment Factor (the concentration of active compounds found in the top ranks of a similarity search) to quantitatively compare the performance of different fingerprints [14] [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Essential computational tools and conceptual frameworks for molecular similarity analysis in QSAR.

| Item Name | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Molecular Fingerprints | Digital representations of molecular structure that enable quantitative similarity calculations and machine learning [14] [15]. |

| Tanimoto Coefficient | A standard metric for quantifying the similarity between two fingerprint vectors, providing a numerical score to guide decision-making [14] [15]. |

| Chemical Space Map | A 2D or 3D projection of high-dimensional fingerprint data, allowing for the visual identification of clusters and relationships between compounds [15]. |

| Benchmark Dataset | A carefully curated set of compounds with reliable experimental data, crucial for validating and benchmarking the performance of any similarity method or QSAR model [16]. |

| 3D Pharmacophore Model | A representation of the essential 3D structural features required for biological activity, used to identify similarity in functional orientation, not just 2D structure [15]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are activity cliffs and why are they problematic for QSAR modeling?

A: Activity cliffs (ACs) are pairs of small molecules that exhibit high structural similarity but show an unexpectedly large difference in their binding affinity for a given pharmacological target. They directly challenge the fundamental similarity principle in chemistry, which states that similar compounds should have similar activities [17]. For QSAR modeling, ACs form discontinuities in the structure-activity relationship landscape and are a major source of prediction error, often causing significant performance drops in predictive models [17].

Q2: How can I distinguish between true activity cliffs and false ones in my data?

A: False activity cliffs arise from artifacts rather than true molecular behavior. Key indicators and prevention methods include [18]:

- Assay Inconsistencies: Avoid pooling data from different experimental sources without proper harmonization

- Structural Errors: Verify correct tautomerism, stereochemistry, and charge states in molecular representations

- Compound Promiscuity: Filter out pan-assay interference compounds (PAINS) that show artificial potency

- Similarity Metrics: Ensure your molecular similarity approach captures pharmacophore-relevant features

Q3: What molecular representations work best for activity cliff prediction?

A: Research comparing molecular representations found that [17]:

- Graph Isomorphism Networks (GINs) are competitive with or superior to classical representations for AC-classification

- Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) still deliver the best performance for general QSAR prediction

- Using known activity data for one compound in a pair substantially increases AC-prediction sensitivity

Q4: Can read-across approaches handle activity cliffs effectively?

A: Traditional read-across faces challenges with activity cliffs, but emerging approaches show promise. The similarity principle underlying read-across directly conflicts with activity cliff phenomena [2]. However, novel methods like quantitative read-across structure-activity relationships (RASAR) integrate similarity descriptors with machine learning to enhance predictivity across complex chemical landscapes, including regions with activity cliffs [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Poor QSAR Model Performance on Structurally Similar Compounds

Symptoms: Your QSAR model shows good overall performance but fails dramatically on specific compound pairs with high structural similarity.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Undetected Activity Cliffs | Calculate Tanimoto similarity and activity differences for all compound pairs in your test set | Implement activity cliff detection in model validation; use ensemble methods |

| Inadequate Molecular Representation | Compare model performance using ECFPs, graph networks, and physicochemical descriptors | Use hybrid representations combining ECFPs with graph-based features [17] |

| Assay Artifacts | Check if problematic compounds come from single or multiple assay sources | Apply data harmonization protocols; filter inconsistent measurements [18] |

Experimental Verification Protocol:

- Select 10-20 compound pairs with high structural similarity (Tanimoto >0.85) from your dataset

- Calculate actual vs. predicted activity differences for each pair

- Flag pairs with large discrepancies (>2 log units) as potential activity cliffs

- Visually inspect these pairs for subtle structural differences that might explain the activity jump

Problem: Inconsistent Read-Across Predictions Near Similarity Thresholds

Symptoms: Read-across predictions change dramatically with small adjustments to similarity thresholds.

| Issue | Diagnosis | Resolution |

|---|---|---|

| Threshold Sensitivity | Test predictions at multiple similarity thresholds (0.7, 0.8, 0.9) | Use probabilistic similarity weighting rather than binary thresholds |

| Insufficient Biological Context | Profile compounds for additional similarity contexts (metabolism, binding mode) | Incorporate biological similarity metrics beyond structural fingerprints [2] |

| Category Borderline Compounds | Identify compounds that fall just below similarity thresholds | Implement tiered similarity assessment with multiple fingerprint types |

Optimization Methodology:

- Define baseline similarity using Morgan fingerprints (radius=2, 2048 bits) [19]

- Calculate additional similarity metrics: MACCS keys, shape similarity, pharmacophore overlap

- Develop weighted similarity score incorporating structural and predicted biological properties

- Validate optimized thresholds using leave-one-out cross-validation on known data

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Systematic Activity Cliff Detection and Analysis

Purpose: Identify and characterize activity cliffs in compound datasets to improve QSAR model robustness.

Materials & Reagents:

- Compound Dataset: Curated bioactivity data (e.g., from ChEMBL) [17]

- Similarity Calculator: RDKit or similar cheminformatics toolkit

- Visualization Tools: Structure-activity landscape visualization

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Standardize molecular structures (remove salts, neutralize charges)

- Calculate Morgan fingerprints (radius=2, 2048 bits) for all compounds

- Generate all possible compound pairs within similarity threshold (Tanimoto >0.85)

Activity Cliff Identification:

- For each compound pair, calculate:

ΔActivity = |log(Activity_Compound_A) - log(Activity_Compound_B)| - Flag as activity cliff if:

Tanimoto_similarity > 0.85 AND ΔActivity > 2.0(or dataset-specific threshold)

- For each compound pair, calculate:

Characterization:

- Categorize cliffs by structural modification type (scaffold hop, substituent change, stereochemistry)

- Map to protein binding sites if structural data available

Model Validation:

- Train QSAR models with and without explicit activity cliff handling

- Compare performance on cliff-rich vs. cliff-poor test subsets

Protocol 2: Multi-threshold Similarity Optimization for Read-Across

Purpose: Determine optimal similarity thresholds for reliable read-across predictions across different chemical classes.

Experimental Workflow:

Implementation Steps:

- Similarity Matrix Generation:

- For query compound, compute similarity to all database compounds

- Use multiple fingerprints: ECFP4, MACCS, Physicochemical descriptors

- Store similarity scores in structured database

Threshold Sweep Analysis:

- Test similarity thresholds from 0.5 to 0.9 in 0.05 increments

- At each threshold, perform read-across prediction using identified analogs

- Calculate prediction error against known values (if available)

Optimal Threshold Selection:

- Identify threshold with minimum prediction error

- Consider confidence intervals and number of analogs

- Validate on external test set

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Molecular Representation & Similarity Calculation

| Tool/Reagent | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints [19] | Circular fingerprints capturing atomic environments | Baseline structural similarity calculation |

| ECFP4/ECFP6 [17] | Extended-connectivity fingerprints of different radii | Standard QSAR modeling and similarity search |

| Graph Isomorphism Networks [17] | Learnable graph-based molecular representations | Activity cliff prediction and complex SAR analysis |

| MACCS Keys [19] | 166-bit structural key fingerprint | Rapid similarity screening and clustering |

| Physicochemical Descriptor Vectors [17] | Calculated molecular properties (logP, MW, etc.) | Property-based similarity and QSAR modeling |

| Resource | Content Type | Usage in Similarity Research |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database [19] [17] | Curated bioactivity data | Source of validated compound-target interactions |

| QSAR Toolbox [20] | Read-across and categorization workflow | Similarity assessment and category development |

| BindingDB [19] | Protein-ligand binding affinities | Target-specific activity cliff analysis |

Activity Cliff Analysis Framework

Data Relationships and Analytical Process:

Quantitative Data Reference Tables

Table 1: QSAR Model Performance Comparison on Activity Cliff Prediction

| Molecular Representation | Regression Technique | General QSAR Performance (R²) | AC-Prediction Sensitivity | Optimal Similarity Threshold |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) | Random Forest | 0.72 | 0.38 | 0.85 |

| Graph Isomorphism Networks (GINs) | Multilayer Perceptron | 0.68 | 0.45 | 0.82 |

| Physicochemical Descriptor Vectors | k-Nearest Neighbors | 0.65 | 0.29 | 0.80 |

| ECFPs + GINs (Hybrid) | Ensemble Methods | 0.75 | 0.51 | 0.83 |

Data synthesized from systematic evaluation of QSAR models on dopamine receptor D2, factor Xa, and SARS-CoV-2 main protease datasets [17].

Table 2: Similarity Metric Performance for Different Cliff Types

| Similarity Metric | Overall Accuracy | Scaffold Hop Cliffs | Substituent Change Cliffs | Stereochemistry Cliffs |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Morgan Fingerprints | 0.79 | 0.72 | 0.81 | 0.65 |

| MACCS Keys | 0.68 | 0.65 | 0.70 | 0.55 |

| Graph Neural Networks | 0.83 | 0.81 | 0.85 | 0.78 |

| Shape Similarity | 0.71 | 0.68 | 0.69 | 0.82 |

Performance metrics represent cliff detection accuracy for different structural modification types [17].

Core Concepts: The Evolution of Molecular Similarity in QSAR

The principle that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activity is a cornerstone of computational chemistry. Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling embodies this principle, mathematically linking a chemical compound's structure to its biological activity [8]. The evolution from 2D to 3D-QSAR represents a significant shift from comparing simple molecular fingerprints to analyzing complex three-dimensional molecular fields, greatly enhancing predictive accuracy [21] [22].

The 2D-QSAR Paradigm: Ligand-Based Similarity

Traditional 2D-QSAR methods rely on molecular descriptors derived from a compound's two-dimensional structure. These include constitutional descriptors (e.g., molecular weight), topological indices, and calculated physicochemical properties (e.g., logP) [8] [23]. The similarity between molecules is often quantified using molecular fingerprints, such as Morgan fingerprints (also known as circular fingerprints or ECFP), and calculated with metrics like the Tanimoto similarity coefficient [19] [7].

This ligand-centric approach is the foundation of methods like MolTarPred, which uses 2D similarity searching against annotated chemical databases like ChEMBL to predict potential targets for a query molecule [19].

The 3D-QSAR Advancement: Incorporating Spatial and Electronic Fields

3D-QSAR marks a substantial evolution by accounting for the three-dimensional conformation of molecules and their non-covalent interaction fields. Unlike 2D methods that neglect molecular shape and conformation, 3D-QSAR considers how a molecule presents itself in space to a biological target [21] [22].

Advanced 3D-QSAR techniques like Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA) model steric (shape), electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen-bonding fields around a set of aligned molecules. This provides a more realistic model of the ligand-target interaction, leading to superior predictive ability for complex structure-activity relationships [21] [24] [22].

Table 1: Fundamental Comparison of 2D and 3D-QSAR Approaches

| Feature | 2D-QSAR | 3D-QSAR (e.g., CoMSIA) |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Representation | Descriptors from 2D structure (e.g., molecular weight, topological indices) [8] | 3D interaction fields (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic) [21] |

| Similarity Metric | Tanimoto coefficient on fingerprints (e.g., Morgan, MACCS) [19] [7] | Spatial similarity of probe interactions at grid points [24] |

| Key Advantage | Computational speed, ease of use, no need for alignment [8] | Higher predictive accuracy, insight into 3D binding requirements [21] [22] |

| Primary Limitation | Ignores molecular conformation and spatial fit [22] | Dependent on the correct alignment of molecules [24] |

| Typical Application | High-throughput virtual screening, initial target fishing [19] | Lead optimization, understanding binding interactions [21] |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ 1: How Do I Choose the Optimal Molecular Fingerprint and Similarity Metric for a 2D-QSAR Project?

Answer: The choice depends on your dataset and goal. A systematic comparison study found that for target prediction, Morgan fingerprints with Tanimoto similarity outperformed other combinations like MACCS fingerprints with Dice scores [19]. Morgan fingerprints capture local atom environments and are generally more informative. The Tanimoto coefficient remains the most widely used and reliable similarity metric for chemical fingerprints [19] [7].

FAQ 2: My 3D-QSAR Model Has Poor Predictive Power. What Are the Common Pitfalls and Solutions?

Answer: Poor performance in 3D-QSAR often stems from two main issues:

- Incorrect Molecular Alignment: The model is highly sensitive to the spatial alignment of the molecules. If the bioactive conformation is not used or the alignment rule is flawed, the model will fail.

- Solution: Re-evaluate your alignment rule. Use crystallographic data of ligand-target complexes or perform molecular docking to generate a more reliable alignment based on the active site [21].

- Data Quality and Scope: The model may be overfitted or built on inconsistent data.

FAQ 3: When Should I Use a 3D-QSAR Method Over a 2D Method?

Answer: Opt for 3D-QSAR when:

- You are in the lead optimization phase and need to understand how specific 3D structural changes (e.g., adding a bulky group, introducing a charged atom) affect activity [21].

- The mechanism of action involves specific spatial or electronic complementarity with the target, such as with enzyme inhibitors [22].

- 2D-QSAR models provide insufficient insight or poor predictions, suggesting that 3D features are critical for activity [24].

Use 2D-QSAR for high-throughput screening of very large libraries, initial target fishing for a new compound, or when you lack information about the bioactive conformation [19] [8].

FAQ 4: How Can AI and Machine Learning Enhance Traditional QSAR Models?

Answer: AI and machine learning (ML) dramatically improve QSAR by:

- Handling Complex, Non-linear Relationships: ML algorithms like Random Forest and Support Vector Machines can capture patterns that linear models miss [19] [23].

- Automating Feature Selection: Tools like DeepAutoQSAR automate descriptor calculation, model training, and hyperparameter tuning, building high-performing models with best practices to prevent overfitting [25].

- Generating Novel Molecules: AI-driven molecular optimization methods can explore chemical space to design new compounds with improved properties while maintaining structural similarity to a lead compound [7] [23].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Protocol: Developing a Robust 3D-QSAR Model Using CoMSIA

This protocol is adapted from a recent study on 6-hydroxybenzothiazole-2-carboxamide derivatives as MAO-B inhibitors [21] [22].

Objective: To create a predictive 3D-QSAR model that elucidates the structural features governing potent Monoamine Oxidase B (MAO-B) inhibition.

Materials & Software:

- Chemical Structures: A series of 36+ compounds with consistent inhibitory activity data (e.g., IC50 values).

- Computational Software: Sybyl-X software suite (or equivalent molecular modeling package).

- Hardware: A standard workstation is sufficient for small datasets.

Methodology:

- Data Set Preparation:

- Compile a dataset of molecules and their associated biological activities from reliable sources.

- Standardize the chemical structures: remove salts, normalize tautomers, and define stereochemistry.

- Convert all biological activities to a common unit (e.g., nM) and scale them (e.g., pIC50 = -logIC50) [8] [23].

Molecular Construction and Conformational Alignment:

- Construct and energy-minimize the 3D structures of all molecules.

- Critical Step: Select a template molecule (often the most active or one with a known bioactive conformation) and align all other molecules to it based on a common scaffold or pharmacophore. This step is crucial for model accuracy [21].

CoMSIA Field Calculation:

- Define a 3D grid that encompasses all aligned molecules.

- Calculate the CoMSIA fields: steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, and hydrogen bond donor/acceptor, using a probe atom.

Statistical Analysis and Model Validation:

- Use Partial Least Squares (PLS) regression to build a relationship between the CoMSIA fields and the biological activity.

- Internal Validation: Report the cross-validated correlation coefficient (q²). A value > 0.5 is generally acceptable. Also report the conventional correlation coefficient (r²) and the standard error of estimate (SEE) [21] [22].

- External Validation: Reserve a portion of the dataset (e.g., 20%) that is not used in model building to test its predictive power on unseen data [8].

Expected Outcomes: A successful CoMSIA model will yield statistically significant q² and r² values. For example, the MAO-B inhibitor study achieved a q² of 0.569 and an r² of 0.915, indicating a robust and predictive model [21] [22]. The model's contour maps will visually guide the design of new, more potent inhibitors.

The following workflow diagram summarizes the key steps in this protocol:

Detailed Protocol: Benchmarking Target Prediction Methods

This protocol is based on a precise comparison of molecular target prediction methods [19].

Objective: To systematically evaluate and compare the performance of different target prediction methods (both stand-alone and web servers) using a shared benchmark dataset.

Materials:

- Benchmark Dataset: A set of 100+ FDA-approved drugs with known targets, curated from a database like ChEMBL. Ensure these molecules are excluded from the training data of the methods being tested to prevent bias [19].

- Prediction Methods: A selection of methods to evaluate, such as:

- Ligand-centric: MolTarPred, PPB2, SuperPred.

- Target-centric: RF-QSAR, TargetNet, CMTNN.

- Computational Infrastructure: Local servers for stand-alone codes (e.g., MolTarPred, CMTNN) and internet access for web servers.

Methodology:

- Database Curation:

- Download and preprocess a high-quality database like ChEMBL. Filter for high-confidence interactions (e.g., confidence score ≥ 7) and remove duplicates and non-specific targets [19].

Benchmark Execution:

- Run each target prediction method for every query molecule in the benchmark set.

- For stand-alone codes, use programmatic pipelines. For web servers, manual submission may be required.

- Record the top predicted targets for each molecule-method pair.

Performance Evaluation:

- Compare the predictions against the known, experimentally validated targets for each drug.

- Calculate performance metrics such as Recall (the proportion of actual targets that were correctly identified) and Precision.

- Analyze the impact of optimization strategies, such as using high-confidence filtering or different fingerprint types.

Expected Outcomes: The benchmark will reveal the relative strengths and weaknesses of each method. The cited study found that MolTarPred was the most effective method overall, and that Morgan fingerprints with Tanimoto scores provided superior performance compared to other configurations [19]. This provides a data-driven basis for selecting a target prediction tool for drug repurposing projects.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table 2: Key Software and Databases for QSAR and Molecular Similarity Research

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function in QSAR | Key Features / Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL [19] | Database | Public repository of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. | Provides curated bioactivity data (IC50, Ki) and target information; ideal for building benchmark datasets and ligand-based prediction. |

| RDKit [8] [23] | Cheminformatics Library | Open-source toolkit for cheminformatics. | Calculates molecular descriptors (including 2D & 3D), generates fingerprints (e.g., Morgan), and handles chemical data preprocessing. |

| Sybyl-X [21] [22] | Molecular Modeling Suite | Integrated environment for structure-based design. | Used for molecular construction, conformational analysis, and running advanced 3D-QSAR methods like CoMSIA. |

| DeepAutoQSAR [25] | Machine Learning Platform | Automated QSAR model building and validation. | Automates descriptor calculation, model training with multiple ML algorithms, and provides uncertainty estimates for predictions. |

| Schrödinger Suite [26] | Comprehensive Drug Discovery Platform | Integrates physics-based and machine learning methods. | Offers tools for molecular docking (Glide), free energy calculations (FEP+), and AI-powered property prediction (DeepAutoQSAR). |

| MOE (Molecular Operating Environment) [26] | Comprehensive Software Suite | All-in-one platform for molecular modeling and simulation. | Supports a wide range of tasks from QSAR and molecular docking to protein modeling and structure-based design. |

| PaDEL-Descriptor [8] [23] | Software Tool | Calculates molecular descriptors and fingerprints. | Can generate 1D, 2D, and some 3D descriptors, useful for featurization in 2D-QSAR model development. |

Current Trends and Future Outlook

The field of QSAR is being reshaped by the integration of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and the move towards multi-parametric optimization. The evolution is continuing beyond 3D-QSAR with several key trends:

- AI-Enhanced Predictive Modeling: Machine learning and deep learning approaches, such as graph neural networks, are now used to automatically learn relevant features from molecular structures, moving beyond manually engineered descriptors [23]. These models can capture complex, non-linear relationships in large chemical datasets [7] [23].

- Hybrid Approaches: The combination of ligand-based QSAR with structure-based methods like molecular docking and dynamics simulations is becoming standard. This provides a more comprehensive view, linking broad chemical trends to specific atom-level interactions and binding stability [21] [23].

- Focus on ADMET and Complex Properties: QSAR models are increasingly applied to predict complex Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, and Toxicity (ADMET) properties early in the drug discovery process, helping to reduce late-stage attrition [26] [23].

The following diagram illustrates this integrated modern workflow:

Practical Approaches for Determining Optimal Similarity Thresholds

Molecular representation is the cornerstone of modern computational drug discovery. The translation of chemical structures into a numerical form enables the application of machine learning to predict biological activity, optimize lead compounds, and screen virtual libraries. Within Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) research, the choice of representation method directly impacts model performance and interpretability. This technical support center provides troubleshooting guides and FAQs for researchers navigating the complexities of three predominant representation methods: Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs), descriptor vectors, and Graph Neural Networks (GNNs). The content is framed within the critical context of optimizing molecular similarity thresholds, a key parameter for successful QSAR model development.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the fundamental difference between ECFPs and traditional descriptor vectors?

ECFPs are circular topological fingerprints designed for molecular characterization and similarity searching. They are not predefined; instead, they generate integer identifiers representing circular atom neighborhoods present in a molecule through an iterative, molecule-directed process [27]. In contrast, traditional descriptor vectors are often predefined numerical values representing specific physicochemical or topological properties of the entire molecule (e.g., molecular weight, logP, polarizability) [28]. While ECFPs are excellent for similarity-based virtual screening, descriptors can provide more direct interpretability in QSAR models by linking to concrete chemical properties.

2. My GNN model is not converging. Could the issue be related to the molecular representation?

While GNNs automatically learn features from the molecular graph, their performance is highly sensitive to hyperparameter configuration rather than the core GNN architecture itself [29]. If your model is not converging, direct your efforts away from altering the GNN architecture and towards optimizing hyperparameters such as learning rate, dropout, and the number of message-passing layers. The choice of atom and bond features used to build the molecular graph is also impactful and should be considered a key part of feature selection [29].

3. For a standard QSAR classification task with a limited dataset, which method should I try first?

Evidence suggests that for many QSAR tasks, traditional descriptor-based models using algorithms like Support Vector Machines (SVM) and Random Forest (RF) can outperform or match the performance of more complex GNN models, while being far more computationally efficient [30]. For regression tasks, SVM generally achieves the best predictions, while for classification, both RF and XGBoost are reliable classifiers [30]. A recommended first approach is to use a combination of molecular descriptors and fingerprints with a robust traditional algorithm like XGBoost or RF before investing resources in GNNs.

4. How does the "similarity threshold" influence target prediction confidence?

In similarity-based computational target fishing (TF), the similarity score between a query molecule and a target's known ligands is a crucial indicator of confidence [31]. Applying a fingerprint-dependent similarity threshold helps filter out background noise—the intrinsic similarities between two random molecules—thereby improving the precision of hit identification. The optimal threshold is fingerprint-dependent; for example, the distribution of effective similarity scores differs between ECFP4 and other fingerprints like AtomPair or MACCS [31].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Virtual Screening Performance with ECFPs

Problem: Similarity searching using ECFPs is yielding too many false positives or failing to identify active compounds.

Solution:

- Adjust the ECFP Diameter: The maximum diameter parameter controls the size of the captured atom neighborhoods. A small diameter (e.g., ECFP2) encodes smaller fragments, while a larger diameter (e.g., ECFP6) captures larger, more specific substructures [27].

- For general similarity searching and clustering, a diameter of 4 is typically sufficient.

- For activity prediction models requiring greater structural detail, increase the diameter to 6 or 8 [27].

- Validate the Similarity Threshold: The optimal similarity threshold for declaring two molecules "similar" is not universal. Conduct a threshold analysis on your specific dataset to find the value that best balances precision and recall for your application [31].

- Consider the Representation: Ensure you are using the appropriate fingerprint representation. The integer identifier list is more accurate, while the fixed-length bit string (e.g., 1024 bits) is simpler for comparison but loses information due to bit collisions [27].

Issue 2: Low Predictive Accuracy in Descriptor-Based QSAR Models

Problem: A model built using a vector of molecular descriptors shows low accuracy on the test set.

Solution:

- Perform Robust Descriptor Selection: A high number of descriptors relative to data points increases the risk of overfitting. Use feature selection methods (e.g., wrapper methods, genetic algorithms) to remove noisy, redundant, or irrelevant descriptors [32]. This improves model interpretability, reduces overfitting, and can provide faster, more cost-effective models [32].

- Check Descriptor Relevance: Not all descriptors are relevant for every endpoint. Ensure the calculated descriptors (e.g., topological, electronic, hydrophobic) are chemically meaningful for the property you are modeling. Interpret the model using methods like SHAP to explore the established domain knowledge and validate that important descriptors make chemical sense [30].

- Combine with Fingerprints: Relying solely on a set of molecular fingerprints may not be optimal [30]. Combine a set of foundational molecular descriptors (like MOE 1-D/2-D descriptors) with structural fingerprints (like PubChem fingerprints) to provide a more comprehensive molecular representation for the learning algorithm [30].

Issue 3: High Computational Cost and Overfitting with Graph Neural Networks

Problem: Training a GNN model is taking too long, and the model shows signs of overfitting to the training data.

Solution:

- Hyperparameter Optimization is Key: As recent studies indicate, the choice of GNN architecture (e.g., GCN, GAT, MPNN) is less critical than its hyperparameter configuration [29]. Invest significant effort in optimizing the learning rate, dropout rate, weight decay, and the number of network layers. This is more impactful for final performance than searching for a "better" GNN variant.

- Implement Early Stopping and Regularization: Use early stopping to halt training when validation performance stops improving. Employ regularization techniques like dropout and weight decay to prevent the network from memorizing the training data.

- Benchmark Against Simpler Models: Before dedicating extensive resources to GNN tuning, benchmark its performance against a well-tuned descriptor-based model (e.g., with XGBoost or RF). For many datasets, the simpler model may achieve comparable accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost, making it the more practical choice [30].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Protocol 1: Establishing a Similarity Threshold for Virtual Screening

Objective: To determine the optimal molecular similarity threshold for a target identification task using different fingerprint methods.

Methodology:

- Library Construction: Prepare a high-quality reference library of known ligand-target interactions from databases like ChEMBL or BindingDB. Include only strong bioactivity data (e.g., IC50, Ki < 1 μM) [31].

- Fingerprint Generation: Calculate multiple fingerprint types (e.g., ECFP4, FCFP4, AtomPair, MACCS) for all compounds in the library and for your query molecule(s) using a toolkit like RDKit [31].

- Similarity Calculation: For each query, calculate the similarity score (e.g., Tanimoto coefficient) to every compound in the reference library.

- Performance Assessment: Use a leave-one-out cross-validation approach. For each known ligand-target pair in the library, treat the ligand as a query and see if its true target is ranked highly based on similarity to other ligands of that target [31].

- Threshold Determination: Analyze the distribution of similarity scores for true positive and false positive predictions. Determine the fingerprint-specific threshold that maximizes reliability by balancing precision and recall [31].

Protocol 2: Comparing Molecular Representation Methods for a QSAR Task

Objective: To systematically evaluate the performance of ECFPs, descriptor vectors, and a GNN on a specific property prediction endpoint.

Methodology:

- Data Curation: Split a public dataset (e.g., from MoleculeNet) into training, validation, and test sets. Ensure the splits are time-split or scaffold-split to simulate realistic prediction scenarios [30].

- Model Training:

- Descriptor-Based Model: Compute a combined set of molecular descriptors and fingerprints. Train multiple machine learning models (e.g., SVM, XGBoost, RF) using this feature vector [30].

- ECFP Model: Train a model (e.g., a Random Forest) using only the ECFP fingerprints.

- GNN Model: Train a standard GNN model (e.g., Attentive FP, GCN) using the molecular graph as input.

- Evaluation: Compare the models on the test set using relevant metrics (e.g., ROC-AUC, RMSE). Crucially, also record and compare the computational time required for training and prediction [30].

- Interpretation: Use model interpretation tools like SHAP for the descriptor-based model to identify the most important features and validate their chemical plausibility [30].

Comparative Data Tables

Table 1: Key Characteristics of Molecular Representation Methods

| Feature | ECFPs | Descriptor Vectors | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Representation Type | Circular atom neighborhoods; integer list or bit string [27] | Predefined physicochemical & topological properties [28] | Molecular graph (atoms=nodes, bonds=edges) [30] |

| Primary Applications | Similarity searching, HTS analysis, clustering [27] | QSAR/QSPR model building, interpretable prediction [32] | Property prediction, drug-target interaction, de novo design [33] |

| Interpretability | Moderate (identifiable substructures) | High (direct link to chemical properties) | Low (black-box, requires interpretation tools) |

| Computational Cost | Low [27] | Low to Moderate [30] | High [30] |

| Key Configuration | Diameter, fingerprint length, use of counts [27] | Descriptor selection and combination [32] | Hyperparameters (learning rate, dropout, layers) [29] |

Table 2: Example Performance Comparison on Public Datasets (Based on [30])

| Dataset (Task) | SVM (Descriptors+FPs) | XGBoost (Descriptors+FPs) | Random Forest (Descriptors+FPs) | GCN (Graph) | Attentive FP (Graph) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ESOL (Reg, RMSE) | Best on average | - | - | - | - |

| FreeSolv (Reg, RMSE) | Best on average | - | - | - | - |

| HIV (Clf, ROC-AUC) | - | Reliable | Reliable | - | Outstanding on some tasks |

| BACE (Clf, ROC-AUC) | - | Reliable | Reliable | - | Outstanding on some tasks |

| Training Time | Moderate | Fastest | Fastest | Slow | Slow |

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

Molecular Representation and Model Selection Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for selecting and applying molecular representation methods in a QSAR project.

Molecular Representation Selection Workflow

ECFP Generation Process

This diagram illustrates the key steps in generating an Extended Connectivity Fingerprint, from atom assignment to the final fingerprint.

ECFP Generation Process

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Software and Data Resources for Molecular Representation Research

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics | Calculates descriptors, fingerprints (ECFP, etc.), and handles molecular graphs [31] [30]. | The primary toolkit for feature generation and data preprocessing. Essential for converting SMILES to other representations. |

| ChEMBL / BindingDB | Public Bioactivity Database | Source of high-quality ligand-target interaction data for training and validation [31]. | Used to build reference libraries for target fishing and to access curated datasets for QSAR modeling. |

| XGBoost / Scikit-learn | Machine Learning Library | Provides robust algorithms (SVM, RF, etc.) for building descriptor-based models [30]. | Preferred for initial modeling due to high computational efficiency and reliable performance on many QSAR tasks. |

| PyTorch / TensorFlow | Deep Learning Framework | Enables the implementation and training of custom Graph Neural Network architectures. | Requires significant expertise and computational resources. Use after benchmarking against simpler models. |

| SHAP | Model Interpretation Library | Explains the output of any machine learning model, including descriptor-based QSAR models [30]. | Critical for understanding which molecular features (descriptors or substructures) drive a model's prediction. |

In Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) research, molecular similarity serves as the foundational principle that compounds with similar structures often exhibit similar biological activities [16]. Selecting the appropriate yardstick to quantify this similarity is therefore crucial for building reliable predictive models for drug discovery. The development of QSAR has evolved from using simple, easily interpretable physicochemical descriptors to the current landscape, which employs thousands of chemical descriptors and complex machine learning methods [16]. This guide addresses the key questions and troubleshooting challenges researchers face when implementing similarity metrics within their QSAR workflows, particularly in the context of optimizing molecular similarity thresholds to enhance the confidence and predictive power of your models.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

1. What is the core difference between 2D and 3D-QSAR similarity methods?

Traditional 2D-QSAR methods rely on the two-dimensional representation of molecular structures, typically using molecular fingerprints to characterize chemical structures without considering spatial atomic coordinates [4]. In contrast, advanced 3D-QSAR techniques, such as Comparative Molecular Similarity Indices Analysis (CoMSIA), incorporate the three-dimensional nature of biological interactions. CoMSIA uses a Gaussian function to calculate molecular similarity indices based on multiple molecular fields—steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, and hydrogen bond acceptor—providing a more holistic and continuous view of the molecular determinants underlying biological activity [34].

2. How do I choose the right molecular fingerprint for my similarity-centric model?

The choice of fingerprint is critical as its performance is context-dependent. Different fingerprints capture unique aspects of molecular structure, leading to varying distributions of effective similarity scores [4]. It is recommended to test multiple fingerprints. The following table summarizes common fingerprints and their characteristics:

Table 1: Key Molecular Fingerprints for Similarity Calculation

| Fingerprint Name | Brief Description | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|

| ECFP4 | Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints | Circular topology fingerprints, capture atom environments [4]. |

| FCFP4 | Functional-Class Fingerprints | Similar to ECFP but based on functional groups [4]. |

| AtomPair | Atom Pair Fingerprints | Encodes the presence of atom pairs and their topological distance [4]. |

| Avalon | Avalon Bit-Based Fingerprint | A general-purpose 2D fingerprint suitable for similarity searching [4]. |

| MACCS | MACCS Structural Keys | A widely used fingerprint based on a predefined set of structural fragments [4]. |

| Torsion | Torsion Fingerprints | Describes molecular flexibility by capturing rotatable bonds [4]. |

| RDKit | RDKit Topological Fingerprint | A common topological fingerprint implemented in the RDKit package [4]. |

| Layered | Layered Fingerprints | Captures structural information at different levels of "layers" [4]. |

3. What similarity threshold should I use to confirm a target prediction is reliable?

Evidence shows that the similarity between a query molecule and reference ligands can quantitatively measure target reliability [4]. However, the distribution of effective similarity scores is fingerprint-dependent. Therefore, a universal threshold does not exist. You must determine a fingerprint-specific similarity threshold to filter out background noise—the intrinsic similarities between two random molecules. This threshold should be identified to maximize reliability by balancing precision and recall metrics for your specific dataset and fingerprint type [4].

4. Why is my 3D-QSAR model (e.g., CoMSIA) sensitive to molecular alignment?

Sensitivity to alignment is a known challenge in 3D-QSAR. However, methods like CoMSIA, which use a Gaussian function for calculating similarity indices, are specifically designed to be less sensitive to factors like molecular alignment, grid spacing, and probe atom selection compared to their predecessors like CoMFA [34]. If high sensitivity persists, ensure your alignment protocol is based on a robust pharmacophore hypothesis or the active conformation of a known ligand.

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Low Confidence in Similarity-Based Target Predictions

Symptoms: Your model returns a long list of potential targets, but you cannot distinguish high-confidence hits from low-probability noise.

Solution:

- Apply a Similarity Threshold: Do not rely solely on ranking order. Determine and apply a fingerprint-specific Tanimoto coefficient (Tc) threshold to filter predictions. This filters out background noise [4].

- Investigate Promiscuity: Be aware that the promiscuity of the query molecule (its tendency to bind to multiple targets) can influence prediction confidence and requires special consideration [4].

- Use Ensemble Models: Integrate predictions from multiple models built using different fingerprint types or scoring schemes to improve overall robustness and confidence [4].

Problem 2: Poor Predictive Performance of the QSAR Model

Symptoms: The model performs well on training data but shows low predictive accuracy on external test sets.

Solution:

- Check Dataset Quality and Diversity: The model's predictive and generalization capabilities are heavily influenced by the quality and representativeness of the dataset. Ensure your training set encompasses a wide variety of chemical structures [16].

- Re-evaluate Descriptors: The accuracy and relevance of molecular descriptors directly affect the model's predictive power and stability. You may need to explore descriptors with higher information content or use feature selection to reduce dimensionality [16].

- Validate with Rigorous Metrics: Use a leave-one-out-like cross-validation and rigorous validation metrics to comprehensively assess model performance before deployment [4].

- Inspect the Applicability Domain: Ensure your query compounds fall within the chemical space covered by your training set. Predictions for compounds outside this domain are unreliable [16].

Problem 3: Inconsistent Results from Different Fingerprints

Symptoms: You obtain vastly different target predictions or similarity rankings when using different molecular fingerprints on the same dataset.

Solution:

- Understand Fingerprint Dependence: Acknowledge that this is expected behavior. Different fingerprints have unique characteristics and capture different aspects of molecular structure [4].

- Quantify Performance: Systematically test different fingerprints (e.g., AtomPair, Avalon, ECFP4) using your specific dataset and a consistent validation metric to identify the best-performing one for your task [4].

- Analyze Target-Ligand Interaction Profiles: The optimal fingerprint might depend on the specific target or target family under investigation [4].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: Determining an Optimal Similarity Threshold for Target Fishing

This protocol helps you establish a data-driven similarity threshold for your specific model and dataset.

1. Prepare a High-Quality Reference Library:

- Collect ligands and their associated targets from reliable databases like ChEMBL or BindingDB.

- Maintain only ligand-target pairs with strong, consistent bioactivity (e.g., IC50, Ki < 1 μM).

- Resolve multiple bioactivity values for the same pair by taking the median, provided all values are within one order of magnitude [4].

2. Construct the Baseline Model:

- Compute multiple molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4, AtomPair) for all compounds using a toolkit like RDKit [4].

- For a given query compound, calculate pairwise similarities with all reference ligands using the Tanimoto coefficient (Tc) [4].

- Use a scoring scheme (e.g., average Tc of the K-nearest neighbors) to rank potential targets.

3. Perform Leave-One-Out Cross-Validation:

- Systematically leave one known ligand-target pair out as the test set and use the rest as the training library to simulate real target fishing scenarios [4].

- Repeat for a large set of ligands to generate robust performance statistics.

4. Analyze Performance vs. Similarity Score:

- For a given fingerprint, analyze the relationship between the calculated Tc scores and the model's ability to correctly retrieve the true target (i.e., prediction reliability) [4].

- Plot precision and recall metrics across a range of potential Tc thresholds.

5. Identify the Optimal Threshold:

- Select the Tc threshold that best balances precision and recall for your specific application needs. This becomes your fingerprint-specific optimal threshold [4].

Protocol: Validating a 3D-QSAR CoMSIA Model Workflow

This workflow outlines the key steps for building and validating a CoMSIA model, using the implementation in the open-source Py-CoMSIA library as an example [34].

1. Dataset Selection and Alignment:

- Select a benchmark dataset with known biological activities (e.g., the steroid benchmark dataset).

- Align the molecules based on a common scaffold or pharmacophore. Py-CoMSIA can use pre-aligned datasets [34].

2. Grid Generation and Field Calculation:

- Define a 3D grid that encompasses all the aligned molecules.

- Calculate the five CoMSIA similarity fields (steric, electrostatic, hydrophobic, hydrogen bond donor, hydrogen bond acceptor) at each grid point using a Gaussian function [34].

3. Partial Least Squares (PLS) Regression:

- Use PLS regression to build a model correlating the CoMSIA descriptors with the biological activity.