Navigating a Research Career in Molecular Engineering: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals exploring career paths in molecular engineering.

Navigating a Research Career in Molecular Engineering: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals exploring career paths in molecular engineering. It covers the field's interdisciplinary foundations, core methodological and AI-driven approaches, practical troubleshooting strategies for the lab, and the critical frameworks for validating research. By synthesizing current trends and real-world challenges, the article serves as a roadmap for building a successful research career that bridges scientific discovery and technological innovation.

The Molecular Engineering Landscape: Building an Interdisciplinary Foundation for Your Research Career

Molecular engineering represents a fundamental shift in technological problem-solving, moving away from the traditional approach of working with prefabricated materials whose macroscopic properties are already fixed. Instead, this emerging field employs a "bottom-up" design methodology where materials, devices, and systems are deliberately constructed from their constituent atoms and molecules to achieve specific, pre-determined functions [1]. This approach, first articulated by Arthur R. von Hippel in 1956, stands in stark contrast to conventional "top-down" engineering methods and has been further developed through key conceptual advances in nanotechnology [1]. By directly manipulating molecular structure to influence macroscopic system behavior, molecular engineering creates a rational design framework that complements the traditional cycles of inquiry and discovery with deliberate invention and design [2].

The highly interdisciplinary nature of molecular engineering draws upon principles and methodologies from chemical engineering, materials science, bioengineering, electrical engineering, physics, mechanical engineering, and chemistry [1]. This convergence of disciplines is essential for addressing complex technological challenges that transcend traditional domain boundaries. Molecular engineering prepares professionals for leadership roles across research, technology development, and manufacturing, with graduates positioned to pursue paths in traditional engineering, further postgraduate study, or leveraged quantitative problem-solving skills in fields like consulting, finance, and public policy [2]. The field's development of fundamentally new materials and systems addresses outstanding needs across numerous sectors including energy, healthcare, and electronics, often making trial-and-error approaches obsolete due to their cost and complexity in accounting for multivariate dependencies in sophisticated technological systems [1].

Core Principles and Methodologies

The "Bottom-Up" Design Framework

The foundational principle of molecular engineering involves the deliberate design and testing of molecular properties, behavior, and interactions to assemble superior materials, systems, and processes for specific functions [1]. This rational engineering methodology stands in direct opposition to empirical approaches that rely on well-described but poorly-understood correlations between a system's composition and its properties. Instead, molecular engineers manipulate system properties directly through a detailed understanding of their chemical and physical origins [1]. This approach has become increasingly necessary as technological sophistication has advanced, rendering trial-and-error methods both costly and impractical for complex systems where accounting for all relevant variable dependencies proves challenging [1].

Molecular engineering efforts employ both computational tools and experimental methods, often in combination, to achieve their design objectives [1]. The computational and theoretical approaches include techniques such as molecular dynamics, density functional theory, Monte Carlo methods, and molecular mechanics, while experimental methodologies encompass advanced microscopy, spectroscopy, surface science, and synthetic methods [1]. This integrated methodology enables engineers to traverse the entire development pathway from design theory to materials production, and from device design to product development—a critical challenge that requires bringing together critical masses of expertise across multiple disciplines [1].

Essential Analytical Techniques and Instrumentation

Molecular engineers utilize sophisticated tools and instruments to fabricate and analyze molecular interactions and material surfaces at the nano-scale. The increasing complexity of molecules being introduced at surfaces requires ever-evolving analytical capabilities to characterize surface characteristics at the molecular level [1]. Concurrently, advancements in high-performance computing have dramatically expanded the use of computer simulation for studying molecular-scale systems [1].

The experimental toolkit for molecular engineering includes several categories of advanced instrumentation. Microscopy techniques such as atomic force microscopy (AFM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), and scanning tunneling microscopy (STM) provide unprecedented visualization capabilities at molecular and atomic scales [1]. Molecular characterization methods including chromatography, diffraction, and electrophoresis enable detailed analysis of molecular properties and interactions. Spectroscopic techniques such as mass spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and X-ray photoelectron spectroscopy (XPS) provide additional layers of molecular-level information crucial for rational design [1].

Recent breakthroughs in quantitative molecular analysis demonstrate the rapid advancement of these capabilities. A 2025 study published in the Journal of the American Chemical Society detailed a quantitative analysis strategy for small molecules confined in ZSM-5 zeolite materials, using low-dose transmission electron microscopy to visualize molecular structures with angstrom spatial resolution and precisely calibrate the quantity of small molecules within each zeolite channel [3]. This approach advances the study of molecular sorption, transport, and reaction dynamics while enhancing understanding of microscale mechanisms, host-guest interactions, molecular geometry, and responses to external stimuli [3].

Table 1: Core Methodological Approaches in Molecular Engineering

| Method Category | Specific Techniques | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Approaches | Molecular Dynamics, Density Functional Theory, Monte Carlo Methods, Molecular Mechanics | Molecular modeling and simulation, prediction of molecular properties and behaviors |

| Microscopy | Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM), Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM), Scanning Tunneling Microscopy (STM) | High-resolution imaging of molecular and atomic structures |

| Molecular Characterization | Chromatography, Diffraction, Electrophoresis | Separation and analysis of molecular mixtures and structures |

| Spectroscopy | Mass Spectrometry, Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR), X-ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy (XPS) | Determination of molecular structure, composition, and interactions |

| Surface Science | Langmuir-Blodgett Trough, Self-Assembled Monolayers | Creation and analysis of molecular surface films and structures |

| Synthetic Methods | Atomic Layer Deposition, Molecular Beam Epitaxy, DNA Origami | Precise fabrication of molecular structures and materials |

Computational Frameworks: Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationships (QSAR)

Fundamental Principles and Historical Development

Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling represents a powerful computational framework within molecular engineering that uses molecular descriptors and mathematical models to quantitatively describe the relationship between chemical structure and biological activity [4]. QSAR operates on the fundamental premise that a compound's biological activity is primarily determined by its molecular structure—a hypothesis substantiated by chemical practice where compounds with similar structures often exhibit similar activities, following the principle of molecular similarity [4]. This approach extends the qualitative observations of Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) into quantitative predictive models that enable more precise molecular design, particularly in pharmaceutical applications [4].

The development of QSAR methodologies spans more than six decades, beginning with American chemist Corwin Hansch's introduction of Hansch analysis in the 1960s, which predicted biological activity by quantifying fundamental physicochemical parameters including lipophilicity, electronic properties, and steric effects [4]. This early approach utilized few easily interpretable physicochemical descriptors and simple linear models. Over subsequent decades, the field underwent significant transformation, evolving to incorporate thousands of chemical descriptors and complex machine learning methods—both linear and nonlinear—driven by advancements in cheminformatics [4]. Throughout this evolution, continuous innovations in datasets, descriptors, and modeling methods have been central to enhancing both the interpretability and predictive power of QSAR models.

Modern QSAR Components and Workflows

Contemporary QSAR modeling relies on three fundamental components: high-quality datasets, comprehensive molecular descriptors, and sophisticated mathematical models. Dataset quality profoundly influences model performance, requiring structural information coupled with rigorously acquired biological activity data that encompasses diverse chemical structures to ensure reliable prediction and generalization capabilities [4]. Molecular descriptors serve as critical tools for converting chemical structural features into numerical representations, requiring comprehensive representation of molecular properties, correlation with biological activity, computational feasibility, distinct chemical meanings, and sufficient sensitivity to capture subtle structural variations [4]. The accuracy and relevance of descriptors directly affect model predictive power and stability.

Mathematical models form the bridge between molecular structure and activity, having evolved from early linear regression approaches to contemporary machine learning and deep learning techniques that demand substantial computational resources [4]. Modern QSAR workflows incorporate techniques such as feature selection, model optimization, cross-validation, and dimensionality reduction to enhance prediction accuracy and generalization capability while managing computational complexity [4]. The descriptor landscape has expanded to include representations ranging from 0D (constitutional descriptors reflecting molecular composition) to 4D (incorporating multiple molecular conformations and their interactions), with each level offering distinct advantages and limitations in information content and complexity [4].

Figure 1: QSAR Modeling Workflow - This diagram illustrates the iterative process of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship modeling, from initial data collection through molecular optimization and design.

Experimental Protocol: QSAR Model Development

Phase 1: Dataset Curation and Preparation

- Compound Selection: Curate a diverse set of chemical structures with experimentally determined biological activity values (e.g., IC50, EC50, Ki) from reliable sources such as ChEMBL or PubChem [4].

- Data Preprocessing: Apply rigorous curation procedures including removal of duplicates, structural standardization, and assessment of activity data reliability. Divide the dataset into training (∼80%), validation (∼10%), and test sets (∼10%) using rational division methods such as sphere exclusion or Kennard-Stone sampling to ensure representative chemical space coverage [4].

- Applicability Domain Definition: Establish the chemical space boundaries within which the model can provide reliable predictions based on the structural diversity of the training set [4].

Phase 2: Molecular Descriptor Calculation and Selection

- Descriptor Generation: Calculate comprehensive molecular descriptors using software such as Dragon, PaDEL, or RDKit, encompassing constitutional, topological, geometrical, and quantum chemical descriptors [4].

- Descriptor Preprocessing: Remove constant or near-constant descriptors, address missing values, and normalize descriptor values to comparable scales [4].

- Feature Selection: Apply dimensionality reduction techniques such as Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or feature selection methods including genetic algorithms, stepwise selection, or correlation-based filtering to identify the most relevant descriptors while minimizing redundancy [4].

Phase 3: Model Building and Validation

- Algorithm Selection: Choose appropriate modeling techniques based on dataset characteristics, including multiple linear regression (MLR), partial least squares (PLS), support vector machines (SVM), random forests (RF), or neural networks (NN) [4].

- Model Training: Optimize model parameters using the training set with techniques such as grid search or evolutionary algorithms, employing cross-validation to avoid overfitting [4].

- Model Validation: Rigorously assess model performance using the external test set through statistical metrics including R², Q², RMSE, and MAE. Validate model robustness using Y-randomization and apply domain of applicability analysis to define reliable prediction boundaries [4].

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Engineering Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|

| ZSM-5 Zeolite | Microporous framework for molecular confinement and catalysis | Study of molecular sorption, transport, and reaction dynamics [3] |

| Silver Nanoparticles | Antibacterial agent incorporated into surface coatings | Development of antimicrobial surfaces and consumer products [1] |

| Organic Semiconductor Materials | Electron-conducting components for electronic devices | Fabrication of organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) and flexible electronics [1] |

| CRISPR Components | Gene editing machinery | Genetic engineering and synthetic biology applications [1] |

| Polyelectrolyte Micelles | Nanoscale delivery vehicles | Drug formulation and targeted therapeutic delivery [1] |

| DNA-Conjugated Nanoparticles | Programmable building blocks | 3D assembly of functional nanostructures and materials [1] |

AI and Machine Learning Revolution

Transformative Impact on Molecular Modeling

Artificial intelligence and machine learning are fundamentally reshaping molecular engineering by enabling the extraction of complex patterns and correlations from high-dimensional biological and chemical datasets [5]. The AI revolution in structural biology was dramatically demonstrated by Google's DeepMind with its AlphaFold 2 model, which solved the long-standing challenge of predicting protein 3D structures from amino acid sequences with remarkable accuracy [6]. This breakthrough not only addressed a fundamental scientific puzzle but also demonstrated AI's capacity to learn complex physical and chemical principles directly from data, establishing a precedent for tackling other sophisticated challenges in molecular design and engineering [6]. The significance of this advancement was recognized with the 2024 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, underscoring the transformative potential of AI in molecular sciences [6].

At leading research institutions like the University of Chicago's Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, AI research is organized around three strategic goals. The first focuses on developing AI-guided design-build-test-learn loops and autonomous discovery systems ("self-driving labs") that augment traditional theoretical, computational, and experimental approaches to massively accelerate molecular modeling and simulation [5]. The second aims to advance AI applications for molecular materials and systems understanding, discovery, and design, creating new foundational methods to accelerate simulations, develop quantum-level accuracy materials models, and establish techniques for data-driven molecular and protein design [5]. The third pursues the development of novel AI-enabled algorithms and computing hardware, including explainable AI and physics-aware AI, to extract patterns from complex biological data and design advanced molecular structures for applications including carbon capture and catalysis [5].

Experimental Protocol: AI-Driven Molecular Design

Phase 1: Problem Formulation and Data Preparation

- Objective Definition: Clearly specify target molecular properties or activities, such as binding affinity to a specific protein, solubility, or metabolic stability.

- Training Data Assembly: Curate a comprehensive dataset of molecules with associated experimental measurements for the target properties, ensuring chemical diversity and data quality through rigorous curation procedures [4].

- Molecular Representation: Convert molecular structures into machine-readable formats such as SMILES strings, molecular graphs, or 3D coordinate representations suitable for AI model input [4] [6].

Phase 2: Model Architecture and Training

- Algorithm Selection: Choose appropriate AI architectures based on the problem characteristics, including graph neural networks (GNNs) for molecular property prediction, generative adversarial networks (GANs) or variational autoencoders (VAEs) for molecular generation, or reinforcement learning for molecular optimization [5].

- Model Training: Implement appropriate training protocols using curated molecular datasets, employing techniques such as transfer learning when data is limited and incorporating physical constraints or domain knowledge to improve model robustness and interpretability [5].

- Validation Framework: Establish rigorous evaluation metrics and validation procedures, including hold-out test sets, computational benchmarking against existing methods, and where feasible, experimental validation of top-predicted compounds [4].

Phase 3: Molecular Generation and Optimization

- Design Generation: Utilize trained generative models to propose novel molecular structures with optimized target properties, applying constraints for synthesizability, drug-likeness, or other relevant criteria [5].

- Multi-objective Optimization: Balance competing molecular properties using Pareto optimization techniques or weighted scoring functions to identify optimal compromise solutions [4].

- Experimental Validation: Synthesize and test top-predicted compounds to validate model predictions, creating feedback loops to iteratively refine AI models based on experimental results [5].

Career Pathways and Research Directions

Emerging Skill Requirements and Professional Opportunities

The evolving landscape of molecular engineering has created demand for professionals with specialized skill sets that bridge traditional disciplinary boundaries. Analysis of current STEM job postings reveals six recurring "must-have" skill clusters for R&D roles in 2025, with particular relevance to molecular engineering [7]. The research and data analysis cluster emphasizes Python, bioinformatics, statistical modeling, and machine learning for applications in healthcare and life sciences R&D [7]. The product and software development cluster focuses on AWS cloud technologies, version control systems, testing frameworks, and programming languages including Python and C++ for engineering design and development [7]. Additionally, CAD-driven engineering skills remain crucial for prototyping and design in engineering manufacturing and healthcare devices [7].

Molecular engineering professionals must also develop competencies in quality and regulatory compliance, particularly ISO/GxP standards and documentation protocols essential for life sciences operations [7]. Cross-functional communication and documentation abilities appear in approximately one-third of job postings, with many positions specifically citing interdisciplinary project requirements that integrate data scientists with bench researchers or mechanical engineers with software developers [7]. Finally, automation and robotics systems expertise is increasingly valued, with approximately 13% of positions referencing capabilities in PLC programming, robotics integration, or IoT-based control systems for applications ranging from high-throughput laboratory screening to advanced manufacturing [7].

Figure 2: Molecular Engineering Skill Requirements - This diagram outlines the core competencies required for modern molecular engineering careers, spanning technical, interdisciplinary, and professional skill domains.

Academic Pathways and Research Training

Formal education in molecular engineering is offered through dedicated programs at leading institutions including the University of Chicago, University of Washington, and Kyoto University [1]. These interdisciplinary institutes draw faculty from multiple research areas to provide comprehensive training that bridges fundamental science and engineering applications. The University of Chicago's Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering, for example, offers a BS degree with three specialized tracks: bioengineering (incorporating organic chemistry, biochemistry, quantitative physiology, and cellular engineering), chemical engineering (focusing on fluid mechanics, kinetics and reaction engineering, and thermodynamics of mixtures), and quantum engineering (emphasizing quantum mechanics, optics, electrodynamics, and quantum computation) [2].

These programs aim to develop quantitative reasoning and problem-solving skills while introducing engineering analysis of biological, chemical, and physical systems [2]. A key component is the capstone design sequence, where students work in small teams to address real-world engineering challenges proposed by industry mentors and national laboratory engineers [2]. Recent projects have included developing self-cleaning textiles with photocatalytic antimicrobial properties, applying machine learning to analyze ultrafast X-ray images of liquid jets and sprays, and evaluating technical and economic barriers for emerging plastic recycling approaches [2]. Alternatively, students may pursue a research sequence that provides structured introduction to the research process while developing hands-on experience through faculty-guided projects [2].

Research Applications and Impact Areas

Molecular engineering finds application across diverse sectors, with particularly significant impact in healthcare, energy, and environmental technologies. In consumer products, molecular engineering enables antibiotic surfaces through incorporation of silver nanoparticles or antibacterial peptides, rheological modification in cosmetics using small molecules and surfactants, and advanced display technologies through organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs) [1]. Energy applications include flow batteries with synthesized molecules for high-energy density electrolytes, lithium-ion batteries with improved electrode binders and electrolytes, and advanced solar cells using organic, quantum dot, or perovskite-based photovoltaics [1].

Healthcare innovations represent a major focus area, with molecular engineering contributing to peptide-based vaccines that induce robust immune responses, nanoparticle and liposome delivery vehicles for biopharmaceuticals, CRISPR gene editing technologies, and metabolic engineering for chemical production [1]. Environmental applications include advanced membranes for water desalination, catalytic nanoparticles for soil remediation, and novel materials for carbon sequestration [1]. These diverse applications demonstrate the field's capacity to address pressing global challenges through molecular-level design and engineering.

The career trajectory of Monica Duron Juarez illustrates the interdisciplinary nature and diverse opportunities within molecular engineering. Initially focused on medical school with backgrounds in chemistry and neurobiology, she transitioned to bio- and immunoengineering through a Master of Molecular Engineering program, attracted by the "interdisciplinary approach of melding science and engineering" that would "open more doors" professionally [8]. This pathway demonstrates how molecular engineering can integrate diverse scientific backgrounds to create new career possibilities in research, technology development, and innovation at the intersection of multiple disciplines.

Molecular engineering represents the frontier of modern technology, fundamentally relying on the integration of chemical engineering, biology, physics, and materials science. This interdisciplinary fusion enables the strategic design and manipulation of molecular properties and interactions to create superior materials, systems, and processes with tailored functionalities [9]. The field has evolved from theoretical concepts introduced by Richard Feynman in 1959, who first proposed the possibility of manipulating atoms and molecules to create nano-scale machines [9]. Today, this vision has materialized into a robust discipline driving innovations across pharmaceutical research, materials science, robotics, and biotechnology, considered a "general-purpose technology" with potential impacts across virtually all industries and areas of society [9].

The essential value of this interdisciplinary blend lies in its problem-solving capability. Molecular engineers function as strategic problem-solvers who comprehend molecular-level interactions and scale these processes effectively [10]. This requires knowledge spanning quantum mechanics from physics, reaction kinetics from chemical engineering, biomolecular interactions from biology, and structure-property relationships from materials science. The convergence of these disciplines accelerates technological advancements in targeted drug delivery, renewable energy systems, advanced computing, and sustainable manufacturing processes that would be impossible within any single disciplinary silo.

Foundational Disciplines and Their Contributions

Chemical Engineering Principles in Molecular Design

Chemical engineering provides the critical framework for scaling molecular-level phenomena into practical applications through principles of transport phenomena, thermodynamics, and kinetics. Modern chemical engineering research focuses on process intensification, designing compact equipment like microreactors where reactions occur faster with improved control [10]. These advances enable more efficient manufacturing processes for pharmaceuticals, specialty chemicals, and materials. The field also contributes significantly to sustainability through developing greener chemical processes, replacing toxic solvents with environmentally benign alternatives like ionic liquids or supercritical CO₂, and utilizing renewable biomass as feedstocks [10].

Chemical engineers are pioneering carbon capture technologies through novel sorbents and solvents that effectively remove CO₂ from industrial emissions or directly from ambient air [10]. They also develop catalytic processes to convert captured CO₂ into valuable products like methanol or polymers, creating economic incentives for emissions reduction [10]. These applications demonstrate how chemical engineering principles enable the translation of molecular-scale phenomena into industrial-scale processes that address global challenges.

Biological Systems and Biomolecular Engineering

Biology contributes the most sophisticated molecular systems known to science, providing templates, components, and inspiration for molecular engineering. The biological influence manifests strongly in biomaterials, tissue engineering, and synthetic biology applications. Researchers develop biocompatible materials and scaffolds that mimic the extracellular matrix to promote cell adhesion, growth, and tissue regeneration [11]. Advanced techniques like 3D bioprinting and organ-on-a-chip technologies create sophisticated models for personalized medicine and drug testing [11].

Synthetic biology represents another significant convergence point, where engineers reprogram cellular machinery using techniques like CRISPR and TcBuster to edit cellular genomes [12]. This enables the creation of microbial factories producing biofuels, therapeutic proteins, or novel biomaterials [10]. The emerging field of immunoengineering further illustrates this integration, applying chemical engineering principles to understand and engineer immune responses for advanced therapeutics [13]. These applications demonstrate how biological principles and components are harnessed and modified through engineering approaches to create novel solutions in medicine and industrial biotechnology.

Physics of Molecular and Quantum Systems

Physics provides the fundamental understanding of atomic and molecular interactions, quantum phenomena, and the analytical tools for characterizing materials. The principles of quantum mechanics are particularly crucial for understanding electron behavior in materials, enabling the development of quantum technologies [14]. Research institutions are exploring molecular qubits with precision, designing protein qubits that can be produced by cells naturally, which opens possibilities for precision measurements at the molecular level [14].

Physical characterization techniques are essential for molecular engineering advancements. Methods including scanning electron microscopy (SEM), transmission electron microscopy (TEM), X-ray diffraction (XRD), and various spectroscopy techniques (XPS, FTIR, Raman) enable researchers to investigate nanoscale and microscale features of materials [11]. Advanced computational methods like density functional theory (DFT) and molecular dynamics (MD) simulations allow virtual materials design and prediction of properties at atomic and molecular levels before synthesis [11]. These physical tools and principles provide the foundation for understanding and manipulating matter at the molecular scale.

Materials Science and Nanoscale Engineering

Materials science provides the critical link between molecular structure and macroscopic properties, enabling the design of materials with tailored functionalities. Advances in nanomaterials have revolutionized materials science, with nanoparticles, nanocomposites, nanowires, and nanotubes enabling novel functionalities in electronics, healthcare, energy, and environmental applications [11]. Smart materials with responsive properties represent another frontier, including shape-memory alloys, piezoelectric materials, and magnetostrictive materials that change properties in response to external stimuli [11].

Table 1: Advanced Functional Materials and Their Applications

| Material Category | Key Examples | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Nanostructured Materials | Graphene, quantum dots, metal-organic frameworks | Energy storage, catalysis, sensors, drug delivery [15] [10] |

| Smart Materials | Shape-memory polymers, piezoelectric crystals | Actuators, sensors, self-healing structures [11] |

| Biomaterials | Biocompatible polymers, bioactive ceramics | Medical implants, tissue engineering, drug delivery [11] |

| Energy Materials | Perovskites, solid electrolytes, catalyst coatings | Solar cells, batteries, fuel cells, hydrogen production [15] [10] |

The session on "Nanostructured and Molecularly Engineered Materials for Energy and Catalysis" at the EKC 2025 conference highlights how researchers are creating complex architectures with tunable properties through molecular-level design [15]. These materials enable breakthroughs in renewable energy, green chemistry, and advanced manufacturing, demonstrating the practical applications of fundamental materials science principles.

Experimental Methodologies in Molecular Engineering

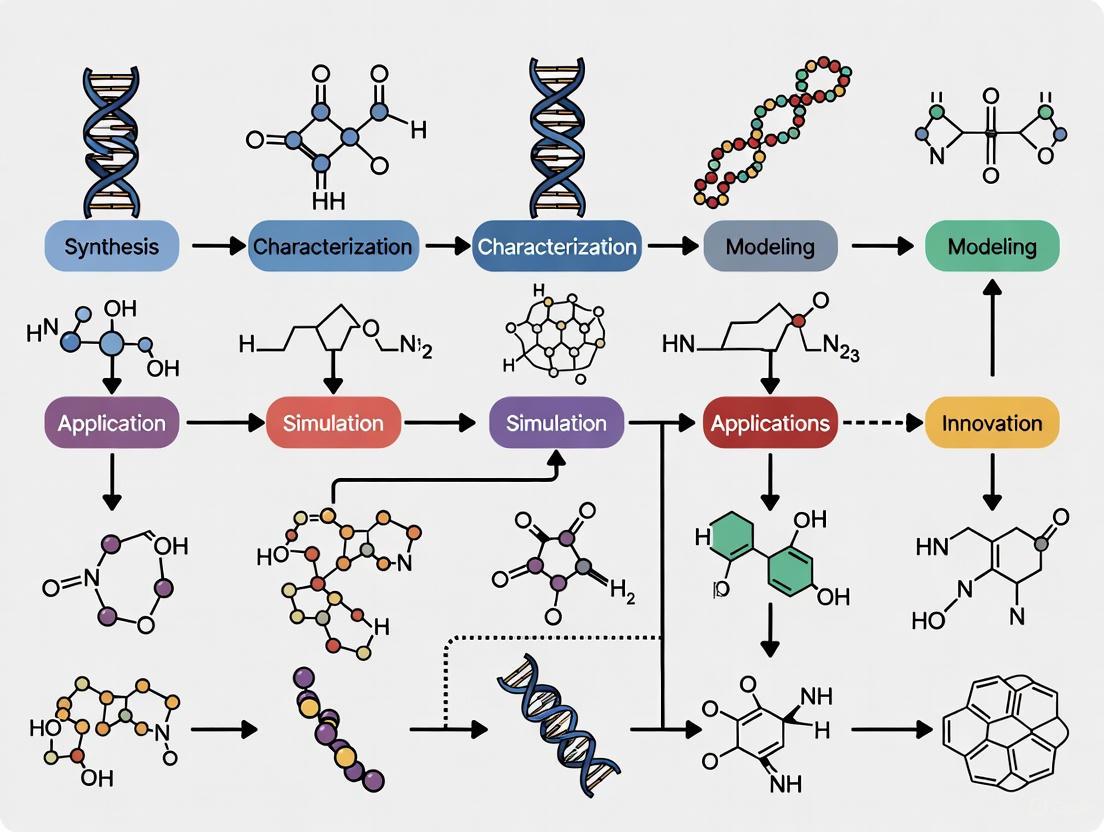

Integrated Workflow for Molecular Engineering

The experimental process in molecular engineering follows a systematic, iterative workflow that integrates techniques from all foundational disciplines. This begins with computational design and molecular modeling, proceeds through synthesis and characterization, and culminates in performance testing and refinement.

Diagram 1: Integrated molecular engineering workflow

Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Molecular engineering research requires specialized reagents and materials that enable precise manipulation and analysis at the molecular scale. These tools form the essential toolkit for experimental work across the discipline.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Materials in Molecular Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Type | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Ionic Liquids | Organic salts liquid at room temperature | Green solvents replacing hazardous organic solvents in synthesis [10] |

| Functional Monomers | Acrylates, vinyl compounds, amino acids | Building blocks for polymers with tailored properties [11] |

| Crosslinking Agents | Glutaraldehyde, genipin, bis-acrylamide | Creating three-dimensional networks in hydrogels and polymers [11] |

| Catalytic Nanomaterials | Platinum, palladium, metal oxides | Accelerating chemical reactions for energy conversion and synthesis [15] [10] |

| Biomolecular Scaffolds | Peptides, collagen, chitosan, hyaluronic acid | Supporting cell growth in tissue engineering [11] |

| Gene Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9, TcBuster transposon | Precise modification of cellular genomes [12] |

Advanced Characterization Techniques

Characterization represents a critical phase in molecular engineering research, requiring sophisticated techniques to probe structure-property relationships at multiple length scales. No single characterization method provides complete information, necessitating complementary approaches that collectively build a comprehensive understanding of materials [15].

Table 3: Advanced Characterization Techniques in Molecular Engineering

| Technique Category | Specific Methods | Key Applications in Molecular Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Microscopy | TEM, SEM, AFM, STM | Nanoscale imaging, surface topography, elemental mapping [15] [11] |

| Spectroscopy | XPS, FTIR, Raman, MS | Chemical composition, bonding, molecular interactions [15] |

| Diffraction | XRD, SAXS | Crystallographic structure, phase identification [11] |

| Thermal Analysis | DSC, TGA | Phase transitions, thermal stability, decomposition [11] |

| Surface Analysis | BET, XPS, ToF-SIMS | Surface area, porosity, surface chemistry [15] |

Modern characterization is evolving toward higher resolution and operational analysis. In situ and operando techniques enable real-time observation of materials under actual working conditions, such as studying battery materials during charge-discharge cycles or catalysts during chemical reactions [15]. These approaches provide dynamic information rather than static snapshots, offering crucial insights into operational mechanisms and degradation processes. Artificial intelligence is increasingly applied to characterization data, enhancing analysis quality and extracting subtle patterns that might escape conventional interpretation [15].

Applications and Career Pathways in Molecular Engineering

Promising Application Domains

The interdisciplinary nature of molecular engineering enables groundbreaking applications across multiple high-impact domains. In healthcare, molecular engineering facilitates tissue engineering, targeted drug delivery systems, and advanced diagnostics [11]. Biomaterials designed to interact with biological systems enable medical implants, wound healing technologies, and tissue repair solutions [11]. The convergence with biology enables innovative approaches in immunoengineering, where chemical engineering principles are applied to understand and manipulate immune responses for therapeutic applications [13].

Energy applications represent another significant domain, where molecular engineers design advanced materials for energy conversion and storage [15]. Research focuses on improving solar cells through novel materials like perovskites, developing next-generation batteries with solid electrolytes, and creating catalyst systems for green hydrogen production [10]. These innovations address critical challenges in clean energy transition and climate change mitigation. Environmental applications include molecularly engineered membranes for water purification, sorbents for carbon capture, and catalytic systems for pollutant degradation [10].

Professional Implementation and Career Trajectories

Molecular engineering qualifications open diverse career paths across multiple sectors. Graduates find opportunities in pharmaceutical research, materials science, robotics, mechanical engineering, and biotechnology [9]. The "general-purpose" nature of the training ensures relevance to virtually all industries dealing with molecular-scale systems [9]. Professional roles span research and development, process design, technical consulting, and entrepreneurship in cutting-edge technological ventures.

Table 4: Career Pathways and Industrial Applications for Molecular Engineers

| Industry Sector | Sample Employers | Typical Roles and Specializations |

|---|---|---|

| Biotechnology & Pharmaceuticals | National Institutes of Health (NIH), Pfizer, Genentech | Drug delivery systems, vaccine manufacturing, therapeutic protein production [10] [16] |

| Energy & Fuels | ExxonMobil, PraxAir, H2Gen Innovations | Battery design, fuel cells, alternative fuels, clean power generation [10] [16] |

| Electronics & Photonics | Naval Research Laboratory, Armstrong World Wide | Semiconductor materials, nanoscale technology, equipment design [11] [16] |

| Advanced Materials | DuPont, W.L. Gore and Associates | Electronic materials, chemical sensors, biocompatible materials [11] [16] |

| Chemical Processing | DuPont, Proctor & Gamble, W.R. Grace | Specialty chemical processing, process design, plant-wide control [16] |

The career prospects for molecular engineers are exceptionally promising, with the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics reporting strong salary potential in related fields like biomedical engineering (median salary of $106,950) and chemical engineering (median salary of $121,860) [9]. These figures reflect the high value placed on the interdisciplinary skill set that molecular engineers bring to technological challenges across diverse industries.

Molecular engineering represents a paradigm shift in technological development, where the intentional design of molecular systems replaces the traditional discovery and optimization approach. This whitepaper has delineated how the integration of chemical engineering, biology, physics, and materials science creates a discipline greater than the sum of its parts, enabling solutions to complex challenges from personalized medicine to sustainable energy. The interdisciplinary methodology allows researchers to not only understand but strategically manipulate matter at the most fundamental levels.

The future trajectory of molecular engineering points toward increasingly sophisticated biomolecular integration, advanced computational design, and sustainable process development. Emerging areas include quantum-enabled technologies [14], synthetic biology for manufacturing [10], and responsive materials systems that adapt to environmental cues [11]. These advancements will continue to blur traditional disciplinary boundaries, creating new professional specializations and industrial applications. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, embracing this interdisciplinary approach is not merely advantageous but essential for driving the next generation of technological innovations that will address pressing global challenges and improve quality of life worldwide.

The field of molecular engineering research represents a convergence of multiple engineering disciplines, driving innovation in areas from drug development to quantum computing. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, understanding the structured academic pathways that feed into this interdisciplinary space is crucial for both career development and strategic research planning. Specialized tracks within traditional engineering programs have emerged as the primary mechanism for developing the sophisticated skill sets required for cutting-edge molecular research. These tracks systematically bridge fundamental engineering principles with specialized applications, creating a talent pipeline capable of addressing complex challenges in therapeutic development, biomaterial design, and quantum-enabled technologies. This technical guide provides a comprehensive analysis of these academic pathways, their experimental methodologies, and their alignment with current research demands in molecular engineering.

Bioengineering Tracks: From Molecular Systems to Medical Devices

Bioengineering programs have evolved well beyond a one-size-fits-all curriculum, now offering sophisticated specialization tracks that target specific sectors within the molecular engineering landscape. These tracks provide structured pathways for developing expertise in interfacing engineering principles with biological systems.

Table 1: Specialized Tracks in Bioengineering

| Track Name | Core Focus | Representative Courses | Associated Career Sectors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biotechnology & Therapeutics Engineering [17] [18] | Utilizes cellular/biomolecular processes to develop therapies, drug-delivery vehicles, and gene/cellular therapies. | Stem Cell Engineering; Therapeutic Development & Delivery; Synthetic Biology; Immunoengineering [17]. | Pharmaceuticals, Biotechnology, Regenerative Medicine, Biomanufacturing [18]. |

| Biomechanics & Biomaterials [19] [17] | Engineering of materials and analysis of mechanical forces for medical applications and tissue interfaces. | Biomechanics; Biomaterials; Tissue Engineering; Mechanical Design of Medical Devices [17]. | Medical Devices/Manufacturing, Biomaterials, Biomaterial Design [20] [18]. |

| Biomedical Instrumentation & Bioimaging [19] [17] | Development of devices, instruments, and imaging technologies for diagnosis, research, and treatment. | Bioimaging; Biosensor Techniques; Optical Microscopy; Python Programming [17]. | Medical Devices, Imaging Technology, Biosensors [20] [18]. |

| Systems & Computational Bioengineering [18] | Multi-scale understanding of biological systems via computational and data science methods. | BME Data Science; Molecular Data Science; Quantitative Biological Reasoning; Bioinformatics [18]. | Computational Biology, Bioinformatics, Precision Medicine, Synthetic Biology [18]. |

These tracks are not merely collections of courses; they represent a pedagogical shift toward creating engineers who can operate at the intersection of biology, medicine, and engineering. For instance, the Systems & Computational Bioengineering pathway explicitly prepares researchers to "obtain, integrate and analyze complex data from multiple scales and sources to develop a quantitative understanding of function" [18], a skill critical for modern drug discovery pipelines. Furthermore, the experimental focus in these tracks is evident in required laboratory courses and design projects, such as the capstone "BME Design Lab" sequence at Cornell, which spans the entire senior year [20].

Experimental Focus: Biotherapeutics Development Workflow

A central methodology in the Biotechnology and Therapeutics track is the development and production of biologics. The following diagram and table outline a generalized experimental workflow and the essential research reagents involved in this process.

Diagram Title: Biologics Process Development Workflow

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Biotherapeutics Development

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| Expression Vectors & Plasmids | Engineered gene constructs for stable integration into host cells (e.g., CHO, HEK293) to produce the target therapeutic protein [21]. |

| Cell Culture Media & Feeds | Chemically defined mixtures of nutrients, vitamins, and growth factors optimized to support high-density cell growth and protein production in bioreactors [18]. |

| Chromatography Resins | Stationary phases (e.g., Protein A, ion-exchange, mixed-mode) for the capture and purification of the target biologic from complex harvest streams [17]. |

| Process Analytics & Assays | Suite of tools (e.g., HPLC, MS, SPR, ELISA) for monitoring critical quality attributes (CQAs) like titer, potency, aggregation, and purity throughout the process [7] [21]. |

Chemical Engineering Tracks: Biomolecular Focus and Sustainable Processes

Chemical engineering has expanded from its traditional roots in process manufacturing to encompass specialized fields that are foundational to molecular engineering research. These tracks often leverage the discipline's core strengths in thermodynamics, kinetics, and transport phenomena and apply them to molecular-level challenges.

Table 3: Specialized Tracks in Chemical Engineering

| Track Name | Core Focus | Representative Courses | Associated Career Pathways |

|---|---|---|---|

| Biomolecular Engineering [22] [23] | Applies chemical engineering principles to biological and biotechnological systems for pharmaceuticals and biotechnology. | Biopharmaceuticals; Metabolic Engineering; Protein Engineering; Molecular Dynamics [22]. | Biopharmaceuticals, Cellular Engineering, Drug Discovery & Manufacturing [24] [22]. |

| Nanomaterials & Nanotechnology [22] | Focuses on science and engineering at the nano-scale for creating novel materials and devices. | Bionanotechnology; Colloids; Polymer Science; Molecular Dynamics [22]. | Nanotechnology, Novel Materials, Bionanotechnology [22]. |

| Sustainability, Energy & Environment [22] | Addresses sustainability, environmental impact, and advanced energy conversion and storage systems. | Batteries; Photovoltaics; Metabolic Engineering; Air Pollution; Separations & Carbon Capture [22]. | Energy Conversion & Storage, Environmental Engineering, Carbon Management [24] [22]. |

| Chemical Design & Manufacturing [22] | The conventional ChE core, covering catalysis, separations, and manufacturing process design. | Machine Learning & Data; Separations & Carbon Capture; Polymer Science; Colloids [22]. | Chemical Processing, Consumer Products, Polymer Materials [24] [22]. |

The Biomolecular Engineering concentration, offered as a formal option at the University of Illinois Urbana-Champaign, "builds upon the traditional principles of chemical engineering, but specializes in biological and biotechnological systems" [23]. This track is explicitly designed for students targeting the food, pharmaceutical, and biotechnology industries. Similarly, the University of Maryland's track includes advanced courses like Protein Engineering and Metabolic Engineering [22], which are directly applicable to the research and development of new biologic therapies and sustainable chemical production—a key interest for many drug development companies seeking greener manufacturing platforms.

Experimental Focus: Nanoparticle Synthesis and Functionalization

A core methodology in the Biomolecular and Nanomaterials tracks is the synthesis of engineered nanoparticles for drug delivery or diagnostic applications. The workflow involves precise control over reaction conditions to achieve target properties.

Diagram Title: Nanoparticle Synthesis and Drug Loading Workflow

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Nanomedicine

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in Experimental Workflow |

|---|---|

| Biocompatible/Functional Polymers | Polymers (e.g., PLGA, PEG, PEI) forming the nanoparticle matrix or corona, providing structure, stealth properties, and controlling drug release kinetics [22] [21]. |

| Crosslinkers & Coupling Agents | Chemicals (e.g., glutaraldehyde, EDC/NHS, click chemistry reagents) for stabilizing the nanoparticle core or conjugating targeting ligands (peptides, antibodies) to the surface [22]. |

| Targeting Ligands | Biological molecules (e.g., antibodies, peptides, aptamers) attached to the nanoparticle surface to enable active targeting and specific binding to cell surface receptors [18]. |

| Characterization Standards | Calibrated standards (e.g., size standards, zeta potential standards, fluorescence quenchers) for validating the size, charge, and stability of nanoparticles using analytical instruments [7]. |

Quantum Engineering Tracks: Emerging Applications in Health and Technology

Quantum engineering represents a frontier in advanced technology, with pathways increasingly finding relevance in biomedical research and instrumentation. Unlike the more established fields, quantum technologies are often offered as specialized pathways within electrical engineering or physics programs, designed to augment other specializations.

The Quantum Technologies Pathway at the University of Washington is explicitly framed as a supplement to other majors, stating that "undergraduate students should use the Quantum Technologies pathway to augment another BSECE pathway" [25]. This pathway provides the foundation in quantum mechanics required for both understanding existing electronic devices and engineering new ones based on quantum principles. The curriculum covers areas from quantum computing and communication to photonic devices operating at single-photon levels [25].

Career Trajectories and Research Synergies

For molecular engineering researchers, the relevance of quantum engineering lies in its applications. Quantum technologies are poised to significantly impact drug discovery and materials science. As noted in the search results, "Quantum computers are expected to speed up the discovery of new medicines" because calculating a molecule's properties is "exponentially difficult on a classical computer" [25]. This makes the field a critical enabler for computational chemists and pharmaceutical researchers. Furthermore, quantum sensing technologies can lead to the development of advanced biosensors and imaging systems with unprecedented sensitivity, directly impacting diagnostic capabilities [25].

Career paths for graduates with this training include roles such as Quantum Engineer, Research Scientist, Process/Test Engineer, and Optics Engineer [25]. However, the search results indicate that "most positions utilizing quantum mechanics for new technologies require a graduate degree" [25], highlighting the importance of advanced study for those aiming to lead research in this domain. The experimental work in this field is heavily reliant on specialized instrumentation, including cryogenic systems, optical benches, and nanofabrication facilities, as reflected in courses like "Introduction to Quantum Hardware" which offers hands-on access to quantum hardware [25].

Cross-Disciplinary Skill Clusters for the Modern Researcher

Beyond domain-specific knowledge, an analysis of in-demand STEM skills reveals consistent clusters of competencies required across bioengineering, chemical, and quantum engineering roles in R&D settings [7]. These clusters represent the practical, applicable skills that research organizations value.

Table 5: In-Demand R&D and STEM Skill Clusters for 2025

| Skill Cluster | Primary Domains | Key Skills & Technologies |

|---|---|---|

| Research and Data Analysis [7] | Healthcare R&D, Life Sciences R&D | Python, Data Analysis, Bioinformatics, Statistical Modeling, Machine Learning. |

| Product/Software Development for R&D [7] | Healthcare Product Development, Engineering Design & Development | AWS Cloud, Git/Version Control, Testing Frameworks, Programming (Python, C++). |

| CAD-Driven Engineering [7] | Engineering & Manufacturing (Design), Healthcare Devices | CAD Tools (AutoCAD), Prototyping, ISO/Quality Systems. |

| Quality and Regulatory [7] | Engineering & Manufacturing (Quality & Regulatory), Life Science Operations | ISO/GxP Compliance, Documentation Protocols, Qualification/Validation. |

| Clinical Operations [7] | Healthcare Clinical, Life Science Clinical Ops | Patient Care Protocols, Lab Services, AWS Use in Clinical Settings. |

| Infrastructure and Systems [7] | Technical & Operations (Infrastructure), Healthcare/Engineering Operations | AWS Architecture, Security & Monitoring, Automation/CI/CD. |

These skill clusters highlight a critical trend: the integration of computational and data science techniques into all aspects of research and development. For instance, analytical thinking is considered the most sought-after core skill by seven out of ten companies [7]. Furthermore, expertise in cloud computing and automation is increasingly prevalent in job postings for research hospitals and national laboratories, with senior roles in these areas commanding significant compensation [7]. For the modern molecular engineering researcher, proficiency in these skill clusters is as important as domain-specific theoretical knowledge.

The specialized tracks within bioengineering, chemical engineering, and quantum engineering provide defined routes into the multifaceted field of molecular engineering research. The Bioengineering tracks offer deep vertical integration with medical and biological applications, the Chemical Engineering tracks provide a fundamental process-oriented understanding of molecular systems, and the Quantum Engineering pathway presents a forward-looking set of tools with transformative potential for computation and sensing. For researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, engaging with these academic structures is essential for strategic workforce planning, continued professional development, and collaborative partnership. The most successful individuals and organizations will be those that can synthesize knowledge and methodologies across these disciplines, leveraging structured academic pathways to build the interdisciplinary expertise required to solve the next generation of challenges in molecular engineering.

Molecular engineering represents a paradigm shift in technological advancement, operating at the molecular level to design and manipulate materials and systems with unprecedented precision. This discipline transcends traditional engineering boundaries by integrating principles from physics, chemistry, biology, and computational sciences to address humanity's most pressing challenges. For researchers and drug development professionals, molecular engineering offers powerful new toolkits for therapeutic innovation, sustainable energy solutions, and environmental remediation. The field's strategic positioning at the convergence of multiple scientific domains enables unique approaches to complex problems that have historically resisted conventional solutions, making it a critical component of modern research infrastructure and a promising career path for scientists seeking transformative impact.

The foundational premise of molecular engineering lies in understanding and controlling molecular interactions to create materials and systems with tailored functionalities. This molecular-level control enables engineers to design materials atom-by-atom, create targeted drug delivery systems that distinguish between healthy and diseased cells, develop quantum sensors with unprecedented sensitivity, and engineer catalytic processes that convert waste into valuable resources. For professionals in drug development, these capabilities translate to more precise therapeutic interventions, reduced side effects, and accelerated discovery timelines through computational prediction and high-throughput screening methodologies.

Advancing Human Health Through Molecular Design

Immunoengineering and Therapeutic Applications

Immunoengineering represents one of the most transformative applications of molecular engineering in healthcare, employing quantitative methods to understand and therapeutically manipulate the immune system. This approach has yielded significant advances in treating cancer, infections, allergies, and autoimmune diseases by applying engineering principles to immunological challenges [26]. At its core, immunoengineering focuses on reprogramming immune cells to enhance their targeting capabilities and effector functions, creating sophisticated biomaterial scaffolds for controlled immune activation, and developing quantitative models to predict immune system behavior across multiple biological scales.

The molecular engineer's toolkit for immunoengineering includes several specialized platforms. Chimeric Antigen Receptor (CAR) T-cell therapies involve genetically engineering patient-derived T-cells to express synthetic receptors that target specific tumor antigens, creating powerful living drugs against cancer. Biomaterial-based vaccine platforms utilize engineered nanoparticles and scaffolds to control the spatial and temporal delivery of immunomodulatory signals, enhancing the potency and durability of immune responses. Targeted cytokine delivery systems employ molecular engineering to direct potent immune-stimulating or suppressing cytokines specifically to diseased tissues, maximizing therapeutic efficacy while minimizing systemic toxicity. These approaches demonstrate how molecular-level design principles can yield clinical interventions with transformative potential for patient outcomes.

Table: Advanced Immunoengineering Platforms and Applications

| Platform Technology | Key Mechanism of Action | Therapeutic Applications | Development Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| CAR-T Cell Engineering | Genetically modified T-cells with synthetic antigen receptors | B-cell malignancies, multiple myeloma | Clinical approval and next-generation development |

| Lipid Nanoparticle mRNA Vaccines | Non-viral delivery of mRNA encoding antigenic proteins | Infectious diseases, cancer immunotherapies | Clinical approval with expanded applications |

| Artificial Antigen-Presenting Cells | Biomaterial scaffolds displaying T-cell activating signals | Cancer immunotherapy, immune monitoring | Preclinical development |

| Bispecific T-cell Engagers | Antibody derivatives connecting T-cells to tumor cells | Hematological malignancies, solid tumors | Clinical approval and optimization |

Experimental Protocol: CRISPR-Based Genome Editing for Immunotherapy

Title: Non-viral CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing in Primary Human T-cells for Immunotherapy Applications

Background: This protocol describes the efficient genome editing of primary human T-cells using CRISPR-Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes delivered via electroporation, enabling the generation of engineered T-cells for adoptive cell therapies without viral vectors.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Human primary T-cells from leukapheresis product

- CRISPR-Cas9 protein (commercial source)

- Synthetic guide RNA targeting TRAC locus

- Electroporation system (e.g., Neon Transfection System)

- RPMI-1640 medium with IL-2 (200 U/mL)

- Anti-CD3/CD28 activation beads

- Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS), characterized

- DMSO (cell culture grade)

Procedure:

- T-cell Isolation and Activation: Isolate T-cells from PBMCs using Ficoll density gradient centrifugation. Activate T-cells with anti-CD3/CD28 beads at 1:1 bead:cell ratio in complete media (RPMI-1640 + 10% FBS + IL-2) for 48 hours.

- RNP Complex Formation: Complex 10μg of CRISPR-Cas9 protein with 5μg of synthetic guide RNA in electroporation buffer. Incubate at room temperature for 10 minutes to form RNP complexes.

- Electroporation: Wash activated T-cells and resuspend at 20×10⁶ cells/mL in electroporation buffer. Mix 10μL cell suspension with 5μL RNP complex and electroporate using manufacturer's optimized parameters (typically 1600V, 10ms, 3 pulses).

- Recovery and Expansion: Immediately transfer electroporated cells to pre-warmed complete media with IL-2. Remove activation beads after 24 hours. Culture cells at 0.5-1×10⁶ cells/mL, maintaining density and replenishing IL-2 every 2-3 days.

- Validation: Assess editing efficiency 72 hours post-electroporation via flow cytometry (for surface marker knockout) or T7E1 assay/TIDE analysis (for genomic modification).

Troubleshooting:

- Low editing efficiency: Optimize guide RNA design, verify RNP complex formation, and titrate cell concentration during electroporation.

- Poor cell viability: Reduce electric pulse duration, optimize recovery conditions, and ensure immediate transfer to pre-warmed media post-electroporation.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Engineering in Biomedicine

Table: Key Research Reagents for Biomedical Molecular Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Research Function | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Tools | CRISPR-Cas9 RNPs, AAV vectors, TALENs | Targeted gene knockout, insertion, or correction | Off-target effects, delivery efficiency, immunogenicity |

| Nanoparticle Systems | Lipid nanoparticles, polymeric nanoparticles, inorganic NPs | Drug/gene delivery, imaging, diagnostics | Biocompatibility, payload capacity, surface functionalization |

| Cytokines & Growth Factors | IL-2, IL-15, IFN-γ, TGF-β | T-cell expansion, differentiation modulation | Concentration optimization, temporal control |

| Flow Cytometry Reagents | Fluorescent antibodies, viability dyes, cell tracking dyes | Immune phenotyping, functional assessment | Panel design, spectral overlap, sample processing |

| Cell Culture Materials | Activation beads, serum-free media, extracellular matrices | In vitro cell expansion and differentiation | Lot-to-lot variability, xeno-free requirements |

Sustainable Energy Solutions Through Molecular Innovation

Next-Generation Energy Storage and Conversion Systems

Molecular engineering approaches are revolutionizing energy technologies through the rational design of materials for enhanced energy storage, conversion, and efficiency. Research in this domain focuses on developing novel materials for energy harvesting and conversion, advanced battery technologies, and clean catalytic processes [27]. These innovations share a common foundation in the precise control of molecular structure to optimize electron and ion transport, catalytic activity, and interfacial phenomena at critical junctions in energy systems.

Quantum engineering represents a particularly advanced frontier in molecular engineering for energy applications. Quantum-based sensors enable precise monitoring of energy materials under operating conditions, providing unprecedented insight into degradation mechanisms and performance limitations. Quantum computing accelerates the discovery of new energy materials by simulating molecular interactions and properties at scales inaccessible to classical computational methods [26]. These capabilities are transforming the development timeline for energy technologies, moving from serendipitous discovery to rational design.

Table: Molecular Engineering Approaches for Energy Applications

| Technology Platform | Molecular Engineering Strategy | Performance Metrics | Research Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Perovskite Solar Cells | Crystal structure engineering, interface passivation, 2D/3D heterostructures | Power conversion efficiency (>25%), operational stability | Scalable fabrication, long-term stability, lead-free alternatives |

| Solid-State Batteries | Solid electrolyte design, interface engineering, composite electrodes | Energy density, cycle life, safety | Ionic conductivity, interface resistance, manufacturing |

| Electrocatalysts for Fuel Cells | Single-atom catalysts, alloy nanoparticles, metal-organic frameworks | Mass activity, durability, cost reduction | Catalyst stability, membrane performance, fuel flexibility |

| Quantum Dot Solar Cells | Bandgap engineering via size control, surface chemistry manipulation | Tunable absorption, multiple exciton generation | Charge transport, integration with conventional electronics |

Experimental Protocol: Synthesis of Solid-State Electrolyte for Lithium Metal Batteries

Title: Solution-Phase Synthesis of Li₇La₃Zr₂O₁₂ (LLZO) Solid-State Electrolyte with Al doping for High-Performance Batteries

Background: This protocol describes the synthesis of garnet-type LLZO solid electrolyte with aluminum doping to stabilize the cubic phase, enabling high ionic conductivity and compatibility with lithium metal anodes for next-generation batteries.

Reagents and Equipment:

- Lithium nitrate (LiNO₃, 99.99% trace metals basis)

- Lanthanum nitrate hexahydrate (La(NO₃)₃·6H₂O, 99.999%)

- Zirconyl nitrate hydrate (ZrO(NO₃)₂·xH₂O, 99%)

- Aluminum nitrate nonahydrate (Al(NO₃)₃·9H₂O, 99.997%)

- Citric acid (anhydrous, 99.5%)

- Ethylene glycol (anhydrous, 99.8%)

- Tube furnace with controlled atmosphere

- Planetary ball mill with zirconia containers

- Hydraulic pellet press

- Electrochemical impedance spectrometer

Procedure:

- Precursor Solution Preparation: Dissolve stoichiometric amounts of metal nitrates (target composition Li₆.₂₈La₃Zr₂Al₀.₂₄O₁₂) in deionized water with cation ratio Li:La:Zr:Al = 6.28:3:2:0.24. Add citric acid (1.5:1 molar ratio of citric acid to total metal cations) and ethylene glycol (2:1 molar ratio to citric acid).

- Polymerization and Gel Formation: Heat solution at 90°C with continuous stirring for 12 hours to promote esterification and form a viscous gel.

- Combustion and Precursor Formation: Transfer gel to alumina crucible and heat at 350°C for 2 hours in muffle furnace. Spontaneous combustion yields fluffy precursor powder.

- Calcination: Ball mill precursor powder for 2 hours at 300 rpm. Heat treated powder at 900°C for 6 hours in covered alumina crucible with sacrificial powder of same composition to prevent lithium loss.

- Pellet Formation and Sintering: Press calcined powder into pellets at 300 MPa. Sinter pellets at 1150°C for 12 hours in air with heating and cooling rates of 5°C/min.

- Characterization: Measure ionic conductivity via electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) from 25°C to 100°C. Verify phase purity by X-ray diffraction.

Critical Parameters:

- Lithium excess (5-10%) is required to compensate for lithium volatilization during high-temperature treatment.

- Controlled heating/cooling rates prevent cracking of sintered pellets.

- Atmosphere control during sintering is essential to maintain phase purity.

Environmental Protection and Resource Sustainability

Water Resource Management and Materials for Sustainability

Molecular engineering approaches to environmental challenges focus on developing sustainable solutions for water purification, resource recovery, and environmentally benign materials. Research in materials for sustainability encompasses extracting valuable elements from seawater, synthesizing polymers with bio-inspired properties, and engineering self-assembled materials for environmental applications [26]. These technologies share a common foundation in molecular-level design principles that optimize separation, catalytic, and sensing functions for environmental monitoring and remediation.

Advanced membrane technologies represent a particularly impactful application of molecular engineering in water sustainability. Molecularly engineered membranes with precisely controlled pore architectures, surface chemistries, and antifouling properties enable more efficient desalination, wastewater treatment, and resource recovery. These systems often incorporate biomimetic design principles, taking inspiration from biological membranes that achieve remarkable selectivity and efficiency through molecular-level organization. Similarly, molecular engineering enables the development of smart materials that autonomously respond to environmental triggers, such as pH, temperature, or specific contaminants, creating adaptive systems for environmental management.

Table: Molecular Engineering Solutions for Environmental Applications

| Application Area | Molecular Engineering Approach | Key Performance Indicators | Implementation Status |

|---|---|---|---|

| Water Purification | Biomimetic membranes, responsive polymers, photocatalytic nanomaterials | Contaminant removal efficiency, energy consumption, fouling resistance | Pilot-scale demonstration, early commercial deployment |

| Carbon Capture | Metal-organic frameworks, porous polymer networks, functionalized membranes | CO₂ capacity, selectivity, regeneration energy | Laboratory validation, prototype development |

| Resource Recovery | Selective adsorbents, catalytic converters, electrochemical systems | Recovery efficiency, product purity, energy intensity | Laboratory to pilot scale |

| Biodegradable Materials | Engineered polymers, bio-based composites, programmable degradation | Material properties, degradation rate, non-toxic byproducts | Commercial availability for selected applications |

Quantitative and Logic Modeling in Environmental Molecular Engineering

Mathematical modeling represents an essential component of molecular engineering for environmental applications, enabling the prediction and optimization of system behavior before resource-intensive experimental implementation. Quantitative and logic modeling approaches allow researchers to understand complex biomolecular systems whose behaviors cannot be intuitively derived from individual components [28]. These computational tools are particularly valuable for environmental applications where field testing is costly and system-level impacts must be carefully evaluated.

Quantitative models based on chemical kinetics and transport phenomena enable precise prediction of molecular separation efficiency, catalytic activity, and material degradation under operational conditions. These models incorporate fundamental physical principles and molecular interaction parameters to simulate system performance across temporal and spatial scales. Complementarily, logic models provide a framework for understanding qualitative system behaviors, such as threshold responses to pollutant concentrations or switching between different functional states in responsive materials. The integration of these modeling approaches creates powerful in silico platforms for molecular engineering design iteration, significantly accelerating the development timeline for environmental technologies.

Emerging Frontiers and Convergent Technologies

AI-Driven Biomolecular Design and High-Throughput Development

The integration of artificial intelligence with molecular engineering is creating transformative opportunities across health, energy, and environmental applications. AI-powered platforms accelerate genomic analysis, predict protein structures, and optimize molecular designs with unprecedented speed and accuracy [29]. These capabilities are particularly valuable for drug development professionals, enabling the identification of therapeutic targets and optimization of drug candidates through in silico prediction rather than purely empirical screening.

High-throughput experimental systems represent another critical frontier in molecular engineering. Automated laboratory systems allow researchers to rapidly test thousands of molecular variants, while robotic liquid handling ensures reproducibility and precise control of experimental conditions [29]. The combination of CRISPR technology with high-throughput systems enables genome-wide functional studies that systematically identify gene functions and their relevance to disease mechanisms. Similarly, single-cell sequencing technologies provide unprecedented resolution in understanding cellular diversity and function, enabling more precise engineering of cellular therapies and diagnostic tools.

Sustainable Bioprocess Engineering and Green Manufacturing

Molecular engineering approaches are increasingly focused on developing sustainable bioprocesses that reduce environmental impact while maintaining economic viability. Bio-based solutions include developing biodegradable plastics, renewable biofuels, and biological alternatives to petrochemical products [29]. These technologies leverage biological systems as manufacturing platforms, creating molecular products through environmentally benign processes rather than traditional chemical synthesis.

Carbon capture and utilization represents a particularly promising application of molecular engineering for climate change mitigation. Engineered biological systems can capture and convert carbon dioxide into valuable products, including biofuels, plastics, and food ingredients [29]. These approaches transform carbon emissions from waste products into manufacturing feedstocks, creating circular carbon economies that reduce net greenhouse gas emissions. Molecular engineers contribute to these technologies through the design of efficient catalytic systems, optimization of metabolic pathways in production organisms, and development of separation technologies for product purification.

Molecular engineering provides a unified framework for addressing interconnected challenges in health, energy, and the environment through molecular-level design and manipulation. For researchers and drug development professionals, this discipline offers powerful new capabilities for creating targeted therapies, sustainable energy systems, and environmental technologies. The convergence of molecular engineering with artificial intelligence, high-throughput experimentation, and sustainable design principles creates unprecedented opportunities for innovation across multiple sectors.

Career paths in molecular engineering research span academic institutions, national laboratories, and industrial R&D divisions, with opportunities in biotechnology, energy, pharmaceuticals, environmental technology, and materials science. The interdisciplinary nature of molecular engineering enables professionals to transition between application domains while maintaining a consistent foundation in molecular-level design principles. As global challenges in health, energy, and environment continue to evolve, molecular engineering will play an increasingly critical role in developing the sophisticated solutions needed for a sustainable and healthy future.

For molecular engineering researchers, the contemporary career landscape is broadly structured across three primary sectors: academia, industry, and government-funded national laboratories. Each pathway offers distinct environments, missions, and career progression models. Understanding the core characteristics, advantages, and challenges of each sector is crucial for scientists and drug development professionals to navigate their career trajectories effectively. These sectors are not mutually exclusive; many researchers build hybrid careers, moving between them or collaborating across boundaries to leverage the unique strengths of each [30].

The choice among these paths fundamentally influences research direction—from fundamental, curiosity-driven inquiry to mission-oriented applied research and public service. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these ecosystems, with a specific focus on applications within molecular engineering, nanotechnology, and drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Research Sectors

The table below summarizes the key characteristics of the three main research sectors, highlighting differences in mission, funding, work style, and career advancement.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Research Sectors

| Feature | Academia | National Labs | Industry |

|---|---|---|---|

| Primary Mission | Fundamental knowledge creation, education, and publication [30] | Mission-oriented R&D for national challenges (security, energy, health) [31] | Product development and commercialization for market success [30] |

| Typical Employers | Universities, research institutes [30] | Federally Funded R&D Centers (FFRDCs) like Argonne, Sandia, Oak Ridge [31] | Biotech, pharmaceutical, materials science companies [30] [32] |

| Funding Source | Competitive grants (e.g., NSF, NIH) [30] [33] | Primary federal funding from agencies like DOE, DOD, NASA [31] | Corporate R&D budgets; venture capital [30] |

| Research Freedom | High autonomy to pursue self-directed research interests [30] | Aligned with broad agency missions; often team-based on large-scale projects [30] [31] | Directed by company goals and product timelines; lower individual autonomy [30] |

| Work Structure | Flexible schedule with significant time spent on grant writing, teaching, and mentorship [30] | Typically a 9-to-5 structure with greater stability [30] | Typically a 40-hour work week, though project deadlines can dictate hours [30] |

| Career Security | Highly competitive tenure track; reliance on soft money from grants [33] | Historically stable and secure federal employment [30] | Potentially vulnerable to economic downturns and corporate restructuring [30] |

| Compensation | Generally lower than other sectors [30] | Starting salaries often higher than academia, but may stagnate over time [30] | Highest earning potential, with salaries often significantly above academia [30] |

| Career Progression | Faculty ranks (Asst., Assoc., Full Prof.) to administration [30] | Scientific staff to group leader, project manager, or senior scientist [31] | Bench scientist to lab manager, project lead, regulatory affairs, or executive roles [30] |

The Academic Research Pathway

Defining the Environment and Mission