Natural vs. Engineered Molecular Machines: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Therapeutics

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of natural and engineered molecular machines, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals.

Natural vs. Engineered Molecular Machines: A Comparative Analysis for Advanced Therapeutics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive comparison of natural and engineered molecular machines, tailored for researchers and drug development professionals. It explores the fundamental principles of biological nanomachines and the design strategies behind their synthetic counterparts. The scope extends to cutting-edge methodological applications in drug delivery and gene editing, an analysis of key challenges in stability and scalability, and a validation of performance through comparative metrics. The synthesis aims to inform the strategic development of next-generation biomedical technologies.

Deconstructing Nature's Blueprint: The Principles of Biological and Synthetic Molecular Machines

Molecular machines are nanoscale structures, controllable and capable of performing specific machinelike functions such as converting energy into mechanical work or transporting cargo [1] [2]. These entities are fundamental to life, mediating nearly all cellular processes, including cargo transport, energy generation, and cell division [3]. Their discovery and the pioneering synthesis of artificial versions, which earned the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, have blurred the lines between biology and engineering [1]. This guide provides an objective comparison between natural and engineered molecular machines, framing them not as competitors but as complementary technologies advancing nanoscale science. We compare their operational principles, performance metrics under experimental conditions, and therapeutic potential, providing a foundational resource for researchers and drug development professionals navigating this transformative field.

Operational Principles and Fundamental Characteristics

Natural and synthetic molecular machines share the core function of performing work at the molecular scale, yet they diverge significantly in their design, energy sources, and operational contexts.

Natural Molecular Machines

Natural molecular machines are protein-based complexes that have evolved to perform essential functions with high efficiency and specificity. They are characterized by three key features [3]:

- Pronounced Brownian motion due to their nanometer scale.

- Energy derived primarily from ATP hydrolysis, providing a strong, unbalanced driving force.

- The exhibition of periodic orbital motions during operation.

These machines are typically described as following single, highly optimized pathways, though emerging systems biology approaches suggest they may exhibit greater mechanistic heterogeneity and complexity than previously assumed [4].

Synthetic Molecular Machines

Synthetic molecular machines, born from supramolecular chemistry, are human-designed systems that emulate natural principles. Key breakthroughs include Jean-Pierre Sauvage's [2]catenane (1983), Sir J. Fraser Stoddart's molecular shuttle (1991), and Bernard L. Feringa's molecular motor [1]. These systems are structurally diverse, featuring mechanically interlocked components like rotaxanes and catenanes, and are designed to be controlled by external stimuli such as light, pH, or chemical fuels [2] [3]. A primary engineering challenge has been achieving autonomous operation, recently advanced through systems utilizing enzymatic oxidation and chemical reduction in a continuous cycle [5].

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of Natural and Synthetic Molecular Machines

| Characteristic | Natural Molecular Machines | Synthetic Molecular Machines |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Composition | Proteins and protein complexes [3] | Synthetic organic molecules, DNA nanostructures, hybrid materials [2] [3] |

| Typical Size Scale | Nanoscale (molecular weight: tens to hundreds of kDa) [3] | Nanoscale (roughly 1/1000th the width of a hair) [1] |

| Fundamental Motion | Linear propulsion (e.g., kinesin) and rotation (e.g., ATP synthase) [3] | Linear shuttling (e.g., rotaxanes) and rotation (e.g., molecular motors) [1] [2] |

| Primary Energy Source | ATP hydrolysis [3] | Light, chemical fuels, electrochemical gradients, pH changes [3] [5] |

| Inherent Brownian Motion | Pronounced, integral to function [3] | Pronounced, a factor in design [3] |

| Typical Environment | Complex biological milieu (cytoplasm, membrane) | Controlled conditions in research; moving toward biological fluids [2] |

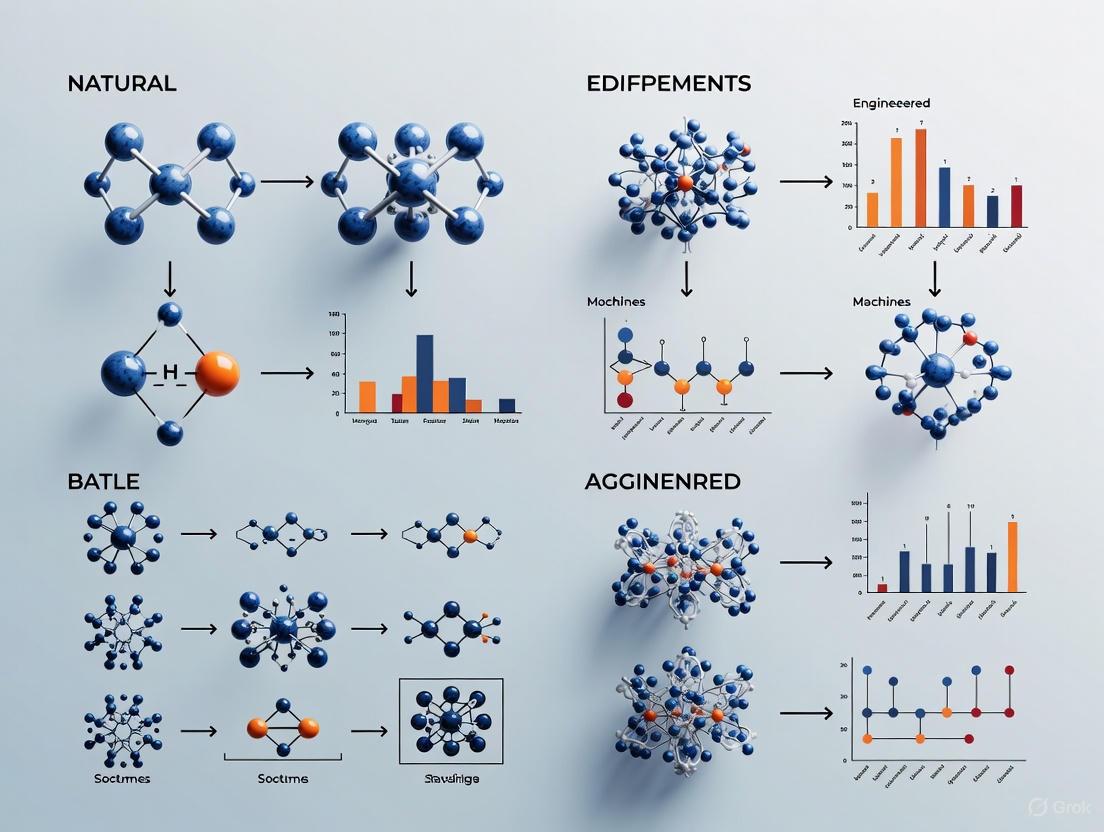

Diagram 1: Operational cycle of molecular machines.

Quantitative Performance Comparison

Objective comparison requires examining hard data on force generation, speed, efficiency, and therapeutic performance. The following tables summarize key experimental findings.

Biophysical and Functional Performance

Table 2: Measured Performance Metrics of Molecular Machines

| Machine Type & Example | Force Generated | Speed / Rate | Efficiency / Energy Input | Experimental Context & Citation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Natural: Kinesin | 5–7 pN [2] | ~100 steps/sec (8 nm/step) [2] | Chemical energy from ATP hydrolysis [3] | In vitro motility assays along microtubules |

| Natural: Myosin | 1–5 pN [2] | Variable, depends on isoform | Chemical energy from ATP hydrolysis [3] | Muscle contraction and actin-based motility |

| Synthetic: Rotaxane-based Lift | ~100 pN [2] | Not specified | Energy from external stimuli (e.g., light) | Surface-based manipulation, AFM measurement |

| Synthetic: DNA Walker | Not specified | ~10 nm/second [2] | Chemical energy from DNA hybridization/strand displacement [2] | Movement along a designed DNA track |

| Synthetic: Redox-driven Motor | Not specified | ~20 hours/360° rotation [5] | Enzyme oxidant (e.g., alcohol dehydrogenase) and chemical reductant (e.g., ammonia borane) [5] | Solution-phase operation with enzymatic fueling |

Therapeutic Performance and Applications

Table 3: Comparison of Applications and Therapeutic Performance

| Application Area | Machine Type | Key Performance Findings | Experimental Model / Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Drug Delivery | Synthetic: Enzyme-sensitive [2]rotaxane | Macrocycle stabilizes drug in bloodstream; enzymatic trigger (β-galactosidase) releases paclitaxel inside tumor cells [3] | In vitro studies with KB cells (human mouth epidermal carcinoma) [3] |

| Membrane Permeabilization | Synthetic: Light-activated rotor | NIR light (2PE) triggers drilling through cell membrane; induces selective cell death [3] | In vitro killing of PC3, HeLa, and MCF7 cancer cell lines with optical precision [3] |

| Controlled Drug Release | Synthetic: Motor-liposome complex | 365 nm light triggers molecular rotation, opening liposome membrane to release small molecules (e.g., calcein) [3] | In vitro model demonstrating on-demand release dependent on motor + UV light [3] |

| Intracellular Transport | Natural: Kinesin/Dynein | Processive movement over micrometers; directional transport of vesicles/organelles along microtubules [3] | Essential function in all eukaryotic cells; reconstituted in in vitro systems |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Reproducibility is paramount. This section details protocols for key experiments measuring the performance and applications outlined above.

Protocol 1: Assessing Synthetic Molecular Machine Performance in Drug Delivery

This protocol outlines the evaluation of an enzyme-sensitive rotaxane for intracellular drug release [3].

- Objective: To determine the efficiency of a [2]rotaxane-based molecular machine in stabilizing a drug payload in circulation and releasing it upon encountering a specific intracellular enzyme.

- Materials:

- Molecular Machine: Synthesized [2]rotaxane 1, incorporating a macrocycle, an enzymatic trigger (a β-galactosidase-sensitive group), and the anticancer drug paclitaxel.

- Cell Line: KB cells (human mouth epidermal carcinoma).

- Key Reagents: Cell culture media, buffers for stability testing, assay kits for quantifying cell viability (e.g., MTT assay).

- Methodology:

- Stability Testing: Incubate the rotaxane-drug conjugate in a simulated bloodstream environment (e.g., serum-containing buffer) at 37°C. Sample at regular intervals and use High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC) to quantify the percentage of intact conjugate and any free paclitaxel released.

- Cellular Uptake and Activation: Culture KB cells. Introduce the rotaxane-drug conjugate to the cell culture medium.

- Intracellular Release: The conjugate enters cells via endocytosis. Inside the cell, the enzyme β-galactosidase cleaves the trigger, decomposing the interlocked architecture and releasing paclitaxel.

- Efficacy Assessment: Measure cell viability after 24-72 hours using an MTT assay. Compare to control groups treated with free paclitaxel or a non-enzyme-sensitive rotaxane control.

- Data Analysis: The half-life of the conjugate in serum and the IC50 value for cell killing are key performance metrics. A successful machine will show high stability in serum but potent efficacy in the target cell line.

Protocol 2: Quantifying Membrane Disruption by Light-Activated Molecular Motors

This protocol describes the method for evaluating cell membrane permeabilization and killing efficacy of a near-infrared (NIR) light-activated molecular motor [3].

- Objective: To demonstrate the targeted killing of specific cancer cells using a peptide-targeted molecular motor activated by NIR light.

- Materials:

- Molecular Motor: A synthetic rotary motor functionalized with a peptide recognition unit for specific cell targeting.

- Cell Lines: Target cancer cell lines (e.g., PC3, HeLa, MCF7) and a non-target control cell line.

- Equipment: Two-photon excitation (2 PE) microscope tuned to 710–720 nm for activation. Viability staining kit (e.g., propidium iodide).

- Methodology:

- Cell Preparation and Targeting: Culture the target and control cells. Incubate the cells with the molecular motor construct to allow peptide-mediated binding to the target cell surface.

- Wash and Irradiate: Gently wash away unbound motors. Expose the culture to NIR light (710–720 nm) via a 3D raster pattern from a two-photon microscope.

- Mechanical Action: The NIR light activates the motors, which undergo rapid rotation, drilling through the cell membrane.

- Viability Quantification: Following irradiation, assess cell death using a viability stain. Propidium iodide, which fluoresces upon entering cells with compromised membranes, is commonly used.

- Data Analysis: Quantify the percentage of dead cells in the targeted (motor + NIR) group versus control groups (no motor + NIR, motor + no NIR, etc.). Specificity is confirmed by low killing in the non-target cell line and the control groups.

Diagram 2: Key research methodologies in molecular machines.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Advancing the field of molecular machines relies on a suite of specialized reagents, computational tools, and experimental platforms.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Machine Research

| Tool / Reagent | Function / Utility | Relevant Machine Type |

|---|---|---|

| Chemputer / XDL | A universal, programmable robotic platform for standardizing and autonomously executing complex chemical syntheses, improving reproducibility [6]. | Synthetic |

| MoleculeNet Benchmark | A large-scale benchmark for molecular machine learning, curating datasets and metrics to standardize the evaluation of property prediction algorithms [7]. | Both |

| Quantum Mechanical (QM) Descriptors (e.g., QMex) | A dataset of quantum-mechanical descriptors used in machine learning models (e.g., ILR) to improve the extrapolative prediction of molecular properties beyond training data [8]. | Synthetic |

| ModelExplorer Software | A computational tool using Monte Carlo sampling to automatically generate and test kinetic models of molecular machine mechanisms, exploring pathway heterogeneity [4]. | Natural |

| Ammonia Borane (Deuterated) | A chemical reductant used in redox-driven molecular motor cycles; deuterated versions help track reaction progress [5]. | Synthetic |

| Alcohol Dehydrogenase | An enzyme used as an oxidant in a novel, autonomous molecular motor cycle, providing spatial control [5]. | Synthetic |

| Photo-sensitive Cyanine Moieties | Light-responsive groups conjugated to membrane proteins to create artificial, light-gated transmembrane channels [3]. | Synthetic |

Natural and synthetic molecular machines represent two powerful, complementary paradigms in nanotechnology. Natural machines offer a benchmark for efficiency, complexity, and seamless integration into biological systems, inspiring synthetic design. Engineered machines provide unparalleled control, programmability, and the ability to operate under non-biological conditions, opening unique therapeutic and technological avenues. The convergence of these fields—powered by automated synthesis, sophisticated computational models, and machine learning—is accelerating the transition from fundamental understanding to real-world application. For researchers and drug developers, the future lies in leveraging the unique strengths of both natural and synthetic molecular machines to create transformative solutions in medicine, materials science, and beyond.

Molecular machines are nature's workhorses, executing essential tasks such as transport, synthesis, and replication within the cell. This guide provides a comparative analysis of key natural molecular machines—myosin, kinesin, ribosomes, and the replisome—framed within the broader research context comparing natural and engineered systems. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the performance metrics, operational mechanisms, and experimental study methods of these biological machines provides crucial insights for designing synthetic analogs and therapeutic interventions. Natural molecular machines operate with efficiencies and specificities that remain aspirational for synthetic systems, yet engineered machines offer unprecedented control and programmability. This comparison delves into the quantitative data and experimental approaches that define their performance, offering a foundation for interdisciplinary innovation.

Comparative Performance Data of Natural Molecular Machines

Table 1: Structural and Functional Comparison of Natural Molecular Machines

| Machine | Primary Function | Track/Substrate | Step Size | Velocity | Energy Source |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesin-1 | Intracellular cargo transport | Microtubule filament | ~8 nm [9] | ~800 nm/s [9] | ATP hydrolysis [9] |

| Myosin XI | Cytoplasmic streaming | Actin filament | ~35 nm [10] | Variable (processive) [10] | ATP hydrolysis [10] |

| Ribosome | Protein synthesis | mRNA template | 1 codon | ~5-20 amino acids/sec [11] | GTP hydrolysis |

| Replisome | DNA replication | DNA template | 1 nucleotide | ~1000 nt/s (bacterial) | ATP hydrolysis |

Table 2: Performance Under Load and Environmental Constraints

| Machine | Stall Force | Processivity | Regulatory Mechanisms |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesin-1 | 6-8 pN [9] | ~1 μm (~100 steps) [9] | Load-dependent kinetics, [9] ATP concentration [9] |

| Myosin XI | Not well characterized | Processive dimer [10] | Cargo binding, [10] calcium signaling |

| Ribosome | Not applicable | Can synthesize entire polypeptides | Translation factors, mRNA structure, nutrient sensing |

| Replisome | Not applicable | Entire genome replication | Checkpoint controls, [12] dNTP availability, DNA damage response |

Experimental Protocols for Studying Molecular Motors

Single-Molecule Optical Trapping for Kinesin and Myosin

Objective: To measure mechanical properties such as velocity, step size, and stall force under controlled loads.

Key Methodologies:

- Fixed Optical Trap: The laser trap remains stationary while the motor moves, resulting in a continuously changing load force. This typically yields a nearly linear relationship between velocity and backward load [9].

- Movable Optical Trap: The trap position is actively controlled via acoustic optical deflectors to maintain constant load on the motor during processive movement. This method typically reveals a sigmoid relationship between velocity and load [9].

Protocol Details:

- Sample Preparation: Purified motor proteins (e.g., kinesin-1) are attached to micrometer-sized beads via engineered chemical linkages [9].

- Flow Chamber Assembly: Microtubules or actin filaments are immobilized on a glass surface within a flow chamber with appropriate buffer conditions.

- Data Acquisition: Bead-motor complexes are captured in optical traps and brought into proximity with immobilized filaments. Movement is recorded at high temporal resolution.

- Force Calibration: Trap stiffness is calibrated using Brownian motion analysis of the trapped bead, typically achieving ~0.1 pN/nm resolution.

- Data Analysis: Step detection algorithms identify discrete 8-nm steps for kinesin [9]. Velocity-force relationships are constructed from multiple traces under varying ATP concentrations.

Key Experimental Variables:

- ATP concentration (affects stepping kinetics) [9]

- Load direction (forward/backward relative to motor directionality)

- Temperature and buffer conditions

- Motor density and bead attachment geometry

Single-Molecule Imaging for Stepping Mechanism Analysis

Objective: To determine the structural states and timing of the mechanochemical cycle.

Key Techniques:

- Total Internal Reflection Dark-Field Microscopy: Utilizes gold nanoparticles (20-40 nm) attached to specific motor domains to visualize state transitions with ~2 nm precision [9].

- Interferometric Scattering Microscopy: Employs smaller gold particles (30 nm) with short linkers for minimal perturbation [9].

- MINFLUX Microscopy: Uses ~1 nm fluorophores for ultra-high precision tracking of head positions [9].

Protocol Details:

- Motor Labeling: Site-specific labeling via cysteine mutations at strategic positions (e.g., S55C in human kinesin) [9].

- Imaging Conditions: Low background illumination with appropriate oxygen scavenging systems for fluorescence methods.

- State Classification: Dwell times in one-head-bound (1HB) and two-heads-bound (2HB) states are measured across ATP concentrations.

- Kinetic Analysis: ATP-binding state is determined based on which dwell time (1HB or 2HB) shows concentration dependence [9].

Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Machine Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent / Material | Function | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Gold nanoparticles (20-40 nm) | Scattering labels for single-particle tracking | Visualizing kinesin head positions [9] |

| Site-specific cysteine mutants | Engineering attachment points for probes | S55C mutation for gold particle attachment [9] |

| Adenosine triphosphate (ATP) | Native energy source for motor proteins | Studying concentration-dependent kinetics [9] |

| Adenosine 5'-[γ-thio]triphosphate (ATPγS) | Non-hydrolyzable ATP analog | Trapping intermediate states |

| Taxol/paclitaxel | Microtubule-stabilizing drug | Maintaining microtubule integrity during assays |

| Orthovanadate (Vi) | Transition-state analog for ATPase | Inhibiting catalytic cycle at specific points |

| Fixed optical trap | Applying resistive load with changing force | Measuring velocity-load relationships [9] |

| Feedback-controlled optical trap | Maintaining constant load during movement | Revealing sigmoidal velocity-force curves [9] |

Operational Mechanisms and Signaling Pathways

Kinesin Stepping Mechanism

Engineering Approaches Comparison

The comparative analysis of natural molecular machines reveals sophisticated design principles that inform emerging synthetic biology and nanotechnology applications. Natural systems like kinesin and myosin demonstrate remarkable mechanical efficiency and precise regulation, while engineered systems offer programmability and novel power sources. For drug development professionals, these insights enable new therapeutic strategies, from light-activated molecular machines for cancer therapy [13] to reusable DNA circuits for sustained drug release [14]. The continuing convergence of biological understanding and engineering capability promises transformative advances in medicine and materials science, as principles from natural molecular machines inspire increasingly sophisticated synthetic analogs.

The intricate molecular machines found in nature, such as kinesin motors that traverse microtubules and membrane transporters that regulate ion flow, have long served as a source of inspiration for synthetic biologists and chemists. [11] These biological marvels demonstrate precise principles of molecular motion, energy conversion, and regulatory control that researchers strive to emulate in engineered systems. This comparison guide examines the current state of synthetic molecular machines—specifically molecular motors, switches, shuttles, and logic gates—contrasting their performance characteristics with natural counterparts and highlighting the experimental approaches used to quantify their function. The fundamental distinction between natural and engineered systems often lies in their design philosophy: natural machines have evolved through evolutionary pressures for biological fitness within cellular environments, while synthetic machines are built through rational design principles emphasizing orthogonality, controllability, and integration with non-biological materials. [15] This framework guides our systematic comparison of how synthetic molecular machines measure against nature's benchmarks and where engineered systems may offer unique advantages for applications in targeted therapy, biosensing, and nanoscale manufacturing.

Molecular Switches: DNA-Based Control Systems

Comparative Performance: Natural vs. Synthetic Switches

Molecular switches form the foundation of regulatory control in both biological and synthetic systems. Natural switches, such as those involved in protein phosphorylation, provide sophisticated regulation through kinase and phosphatase enzymes that process myriad proteins at specific sites for complex cellular signaling. [16] In contrast, synthetic DNA-based switches offer programmable control through designed nucleotide sequences that respond to specific enzymatic triggers.

Table 1: Comparison of Natural and Synthetic Molecular Switches

| Feature | Natural Protein Phosphorylation Switches | Synthetic DNA-Based Switches |

|---|---|---|

| Activation Mechanism | Phosphate group addition/removal by kinases/phosphatases | Enzymatic strand extension/displacement by DNA polymerase/nicking endonucleases |

| Switching Speed | Millisecond to second timescales | Hours for complete switching cycles |

| Energy Source | ATP hydrolysis | dNTP hydrolysis |

| Design Principle | Evolved specificity | Programmable sequence design with TpT barriers to prevent nonspecific reactions |

| Orthogonality | Naturally integrated with cellular processes | Engineered orthogonality through sequence separation |

| Yield | Near-quantitative in proper cellular contexts | ~90% for forward reaction (ON to OFF); ~12% for reverse reaction over 24h |

Experimental Analysis of DNA Molecular Switches

The implementation and validation of synthetic molecular switches rely on carefully designed experimental protocols that demonstrate switching functionality and efficiency. Research on DNA-based switches has established standardized methodologies for characterizing switching performance between ON and OFF states in response to enzymatic triggers. [16]

Experimental Protocol for Type X DNA Switches:

- Switch Construction: Synthesize DNA nanostructures with specific sticky end cohesion sites (x/xC) designed with three-letter coding sequences (A, C, G nucleotides for segment x; C, G, T nucleotides for segment xC) and TpT barriers to prevent undesired extension.

- Forward Reaction (FX) - OFF State: Treat coupled complexes with Bsu DNA polymerase (large fragment) at 37°C for 2 hours or overnight in presence of dTTP, dCTP, and dGTP (no dATP) to enable templated extension exclusively with segment x.

- Backward Reaction (BX) - ON State: Treat decoupled partners with Nt.AlwI nicking endonuclease at 37°C for 1 hour followed by 40°C for 1 hour or overnight to excise extended segments and restore original sticky end pairing.

- Analysis: Characterize reaction yields using native polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE) to quantify assembled vs. disassembled states.

The experimental data demonstrates that synthetic switches achieve robust ON/OFF control with 90% yield for the forward disassembly reaction within 2 hours, though the reverse assembly reaction proceeds more slowly with approximately 12% yield over 24 hours. [16] This performance contrasts with natural phosphorylation switches that typically operate on much faster timescales but with similar high fidelity in proper cellular contexts.

Molecular Motors: From Protein-Based Systems to DNA Nanomachines

Performance Comparison: Natural and Artificial Motors

Molecular motors convert chemical energy into directed mechanical motion, a function critical to both biological systems and prospective nanotechnologies. Natural motors like kinesin achieve directed transport along microtubules with remarkable precision, while synthetic implementations leverage alternative mechanisms such as the "burnt-bridge" principle to achieve directional motion.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Molecular Motors

| Parameter | Natural Kinesin Motors | Lawnmower Protein Motor | DNA-Based Synthetic Motors |

|---|---|---|---|

| Speed | ~1000 nm/s | ~80 nm/s | Variable, typically slower |

| Energy Source | ATP hydrolysis | Peptide bond cleavage (protease activity) | Chemical energy or light |

| Track Guidance | Microtubule filaments | Engineered peptide lawns | Various synthetic tracks |

| Processivity | High (hundreds of steps) | Moderate | Variable by design |

| Directionality | Highly directional | Biased diffusion | Programmable |

| Load Capacity | ~5-7 pN | Not characterized | Limited |

Experimental Characterization of Artificial Motors

The Lawnmower, an autonomous protein-based artificial motor, exemplifies the experimental approaches used to characterize synthetic molecular motors. This system consists of multiple trypsin proteases attached to a spherical hub that cleaves peptide substrates on a surface, generating directional motion through a burnt-bridge Brownian ratchet mechanism. [17]

Experimental Protocol for Lawnmower Motor Characterization:

- Motor Synthesis: Conjugate approximately 500,000 active trypsin molecules to a microspherical hub via surface functionalization, achieving approximately 0.02 trypsins per nm² of surface area.

- Track Preparation: Create two-dimensional peptide lawns by presenting peptide substrates through an F127 polymer brush adhered to a surface, or fabricate one-dimensional tracks through micropatterning for guided motion.

- Imaging and Tracking: Monitor Lawnmower motion using time-lapse microscopy over extended durations (up to 12.5 hours) with 10-second frame intervals.

- Motion Analysis: Calculate mean-squared displacement (MSD) versus time to determine diffusion characteristics (MSD ∝ tα), where α > 1 indicates superdiffusive motion characteristic of active transport.

- Classification: Identify motile Lawnmowers as those with MSD exceeding 10 μm² at τ = 4400 seconds; correct for sample drift by subtracting average trajectory of immotile Lawnmowers.

Experimental results demonstrate that Lawnmowers achieve directional motion with average speeds up to 80 nm/s, comparable to some biological motors, with ensemble-averaged dynamics showing strongly superdiffusive characteristics (αEA = 1.8) at early time points. [17] The motion is saltatory, featuring bursts of directional travel interspersed with quasi-immotile periods, contrasting with the more consistent motion of natural motor proteins.

Molecular Shuttles: Controlled Translational Motion

Natural and Synthetic Shuttling Mechanisms

Molecular shuttles control translational motion along molecular axles, mimicking biological systems that transport cargo within cells. Synthetic shuttles typically employ rotaxane architectures where a macrocycle moves between stations on a linear thread in response to external stimuli.

Single-Molecule Analysis Protocol for Molecular Shuttles:

- Shuttle Design: Synthesize hydrogen-bonded Leigh-type molecular shuttle featuring a tetraamide macrocycle on an oligoethyleneglycol axle with fumaramide (fum) and succinic amide-ester (succ) stations, terminated by diphenylethyl stoppers.

- Hybrid Assembly: Connect single shuttle between two functionalized beads using dsDNA handles - one DNA connects macrocycle to optically trapped bead, another connects fum station stopper to micropipette-held bead.

- Mechanical Testing: Perform pulling-relaxing cycles (200 nm/s rate) to determine mechanical strength of macrocycle-station interactions and measure rupture forces.

- Kinetic Analysis: Apply constant force (~8.5 pN) using feedback-stabilized optical tweezers to monitor real-time shuttling events between stations over minutes.

- Data Collection: Record hundreds of transitions to determine residence times at each station and calculate force-dependent kinetic rates.

Experimental results using this protocol revealed rupture forces of ffum = 8.8 ± 0.6 pN and fsucc = 8.1 ± 0.5 pN, comparable to the strength of multiple hydrogen bonds in biological systems. [18] The free energy of shuttling was calculated as ΔG = 31 ± 2 kBT (approximately 18 kcal/mol), with the distance between stations measured as 15.5 ± 2.5 nm. These quantitative measurements provide crucial parameters for comparing synthetic shuttles with natural transport systems and optimizing future designs.

Molecular Logic Gates: Computational Capabilities at the Nanoscale

Biological and Synthetic Logic Systems

Natural regulatory networks perform complex logical operations through interconnected signaling pathways, while synthetic biology aims to engineer simplified, predictable logic gates for biomedical and biotechnological applications. Recent advances have enabled the creation of protein-based logic gates that execute Boolean operations in therapeutic contexts.

Table 3: Comparison of Natural and Engineered Logic Systems

| Characteristic | Natural Genetic Regulatory Networks | Engineered Protein Logic Gates |

|---|---|---|

| Integration | Highly interconnected with pleiotropic effects | Orthogonal design to minimize cross-talk |

| Logic Operations | Emergent from evolved networks | Programmable AND, OR, NOT gates |

| Components | Transcription factors, promoters, regulatory elements | Bacterial transcription factors, recombinases, CRISPR/Cas |

| Scalability | Complex but difficult to reprogram | Modular design allows expansion to 5+ inputs |

| Design Cycle | Evolutionary timescales | Weeks from design to functional testing |

| Applications | Native biological functions | Targeted therapy, biosensing, controlled bioproduction |

Implementation of Synthetic Biological Logic Gates

The implementation of logic gates in synthetic biology utilizes orthogonal components to minimize interference with host cellular processes while providing programmable control over biological functions. Research in this area has developed standardized architectures for constructing genetic circuits with defined logical operations. [15] [19]

Experimental Framework for Synthetic Gene Circuits:

- Circuit Architecture: Divide circuits into three modules: sensors (detect inputs), integrators (compute logical operations), and actuators (produce outputs).

- Part Selection: Use orthogonal biological components from diverse organisms (e.g., bacterial transcription factors, phage recombinases) to minimize cross-talk with host processes.

- Boolean Implementation: Design series connections of degradable groups for OR gates (cleavage of either group releases cargo) and parallel connections for AND gates (both groups must be cleaved).

- Testing and Validation: Measure circuit performance in model organisms (e.g., E. coli, plants) using reporter proteins (e.g., GFP) to quantify logic fidelity.

Recent advances have dramatically accelerated the design-build-test cycle for protein logic gates, reducing production time from months to weeks and enabling more complex logical operations responsive to up to five different biomarkers. [19] This scalability enhancement represents a significant milestone in closing the gap between natural regulatory networks' complexity and engineered systems' programmability.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Molecular Machine Studies

The study and development of molecular machines requires specialized reagents and tools that enable construction, manipulation, and characterization of these nanoscale systems.

Table 4: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Machine Studies

| Reagent/Tool | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Bsu DNA Polymerase (large fragment) | DNA extension with strand displacement capability | Molecular switch forward reactions [16] |

| Nt.AlwI Nicking Endonuclease | Single-strand DNA cleavage at specific sequences (5'-GGATCNNNN↓N-3') | Molecular switch reverse reactions [16] |

| Trypsin Protease | Peptide bond cleavage for burnt-bridge motor operation | Lawnmower motor propulsion system [17] |

| Optical Tweezers | Single-molecule force measurement and manipulation | Molecular shuttle kinetics studies [18] |

| Orthogonal Transcription Factors | Regulatory elements with minimal host cross-talk | Synthetic gene circuit implementation [15] |

| Site-Specific Recombinases | DNA rearrangement for state switching | Memory elements in genetic circuits [15] |

| dNTPs with Controlled Compositions | Selective template-directed polymerization | Directional control in DNA-based machines [16] |

The comparative analysis of natural and synthetic molecular machines reveals both converging design principles and distinct engineering challenges. Natural systems excel in energy efficiency, integration, and functional complexity evolved for specific biological contexts. Synthetic implementations offer programmability, orthogonality, and customizability for applications ranging from targeted drug delivery to nanoscale manufacturing. While significant progress has been made in emulating natural molecular machines—with synthetic switches achieving 90% yield in forward reactions, protein-based motors reaching speeds comparable to biological counterparts, and logic gates executing multi-input Boolean operations—engineered systems still generally lack the robustness and efficiency of evolved molecular machines. The emerging toolkit of research reagents and experimental methodologies continues to narrow this performance gap, promising enhanced capabilities for controlling matter at the nanoscale through integrative approaches that combine the best features of natural and engineered molecular machines.

Molecular machines, the nanoscale devices that convert various forms of energy into directed mechanical work, represent a fundamental convergence of biological principle and engineering aspiration. In nature, these machines—including motor proteins, ATP synthases, and ion pumps—predominantly rely on the chemical energy stored in adenosine triphosphate (ATP). In contrast, engineered molecular systems increasingly utilize diverse energy inputs such as light, electrical potential, and synthetic chemical fuels. This guide provides a structured comparison of these energy paradigms, offering experimental data and methodologies to facilitate research across biological and engineered nanosystems. The fundamental distinction lies in nature's selection for robust, multifunctional operation within the complex cellular environment, whereas engineering often prioritizes precision, controllability, and integration with human-made systems. Understanding these energy conversion principles provides critical insights for drug development targeting pathological processes and for designing bio-hybrid devices and synthetic biological systems.

The efficiency of energy conversion varies significantly across different molecular machines and energy sources. The table below summarizes key quantitative data for natural and engineered systems.

Table 1: Energy Conversion Efficiencies of Molecular Machines

| Energy Source / System | Reported Efficiency | Key Factors Influencing Efficiency | Experimental Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ATP Hydrolysis (SERCA Pump) [20] | ~12% (estimated) | Membrane lipid composition, Ca²⁺ gradient, thermal dissipation | Reconstituted vesicle system under reduced ion gradient [20] |

| ATP Hydrolysis (Other Natural Motors) | Often claimed near 100% [20] | Coupling mechanism, protein structure, loading conditions | Single-molecule and ensemble measurements |

| Light (Natural Photosynthesis) [21] [22] | 3% to 6% (overall sunlight); Up to 30% (photochemical core) | Photon wavelength, photorespiration, light intensity, metabolic losses | Laboratory measurements of sugar/oxygen production relative to CO₂ uptake [22] |

| Light (Engineered Photovoltaics) [22] | ~10% (average) | Semiconductor material, spectrum management, thermal losses | Standard test conditions for commercial solar cells [22] |

| Electrical (ATP Synthase) [23] | High (Δψ and ΔpH kinetically equivalent) | Proton motive force composition, enzyme activation state | Proteoliposome system with imposed membrane potentials [23] |

| Chemical (Heat to Mechanical Work) [24] | Often <40% (dictated by Carnot equation) | Input (T₁) and output (T₂) temperatures, friction losses | Steam turbines, internal combustion engines [24] |

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

Measuring ATPase Pump Efficiency in Reconstituted Systems

The thermodynamic efficiency of ion pumps like SERCA can be determined using a reconstituted proteoliposome system [20].

Core Workflow:

- Protein Purification: Isolate the ATPase pump (e.g., SERCA) from native tissues or recombinant expression systems.

- Vesicle Reconstitution: Incorporate the purified pump into liposomes of defined lipid composition (e.g., acyl chain length of C16-C20 for maximum SERCA activity).

- Activity Assay: Initiate the reaction by adding ATP to the external solution. Quantify the rate of ATP hydrolysis using a colorimetric or coupled enzymatic assay.

- Ion Transport Measurement: Simultaneously, measure the flux of transported ions (e.g., Ca²⁺ for SERCA) into the liposomes using a radioisotope tracer or fluorescent dye.

- Energetic Calculation:

- Calculate the chemical work performed using the transmembrane ion gradient established: ΔGᵢₒₙ = RT ln([Cout]/[Cin]) + zFΔψ, where z is the ion valence, F is the Faraday constant, and Δψ is the membrane potential.

- Calculate the energy input from the hydrolysis of ATP: ΔGₐₜₚ.

- The thermodynamic efficiency (η) is then estimated as: η = (ΔGᵢₒₙ / ΔGₐₜₚ) × 100%.

Key Considerations: The measured efficiency is highly dependent on the experimental system. The ~12% efficiency for SERCA was observed under nonelectrogenic conditions and a significantly reduced Ca²⁺ gradient, which differs from its native physiological environment [20].

Determining Kinetic Equivalence of Electrical and pH Gradients in ATP Synthesis

A detailed protocol for demonstrating the kinetic equivalence of the electrical (Δψ) and chemical (ΔpH) components of the proton motive force in driving ATP synthesis involves using a well-defined proteoliposome system [23].

- Core Workflow:

- Enzyme Preparation: Use a mutant FoF1-ATP synthase (e.g., from thermophilic Bacillus PS3) with modifications to remove auto-inhibitory domains (e.g., C-terminal domain of the ϵ subunit) to ensure high activity and reproducibility [23].

- Lipid Purification: Critically, remove contaminant potassium ions from the soybean phosphatidylcholine lipid through multiple cycles of centrifugation and resuspension in K⁺-free buffers. Monitor K⁺ levels via atomic absorption spectrophotometry.

- Proteoliposome Reconstitution:

- Solubilize the purified lipid in a detergent (e.g., n-octyl-β-d-glucoside) containing a defined internal buffer (e.g., 40 mM Tricine/MES, pH 8.0) and specific KCl/NaCl ratios.

- Mix with the purified ATP synthase.

- Remove detergent using Bio-Beads SM-2 to form sealed proteoliposomes.

- Imposing Δψ or ΔpH:

- Δψ (K⁺ Diffusion Potential): Incubate proteoliposomes (internal [K⁺] high) in a K⁺-free medium. Add valinomycin (a K⁺ ionophore) to induce K⁺ efflux, generating a membrane potential (inside negative), calculated via the Nernst equation.

- ΔpH (Acid-Base Transition): Pre-incubate proteoliposomes at an internal pH of 8.0, then rapidly mix into an acidic external buffer (e.g., pH 6.0) to create a ΔpH.

- ATP Synthesis Assay: Initiate synthesis by adding ADP and inorganic phosphate (Pi). Quench the reaction at timed intervals and quantify ATP production using a luciferase-based luminescence assay.

- Data Analysis: Plot the initial rate of ATP synthesis against the calculated pmf (where pmf = Δψ + 2.3(kBT/e)ΔpH). The results demonstrate that the synthesis rate depends on the algebraic sum of the two components, confirming their kinetic equivalence within the tested ranges (ΔpH -0.3 to 2.2, Δψ -30 to 140 mV) [23].

Calculating Photosynthetic Efficiency

The efficiency of converting light energy to chemical energy during photosynthesis can be calculated through several methods [21] [22].

Core Workflow:

- Gas Exchange Measurement: Place a leaf or algal sample in a sealed chamber illuminated with a known intensity and spectrum of light.

- Quantify Input and Output:

- Input Energy: Measure the Photosynthetically Active Radiation (PAR, 400-700 nm) incident on the sample using a quantum sensor.

- Output Energy: Monitor the uptake of CO₂ or the evolution of O₂ using infrared gas analyzers or oxygen electrodes.

- Energy Conversion Calculation:

- Convert the moles of CO₂ fixed or O₂ evolved to energy stored in chemical bonds (e.g., the Gibbs free energy for converting CO₂ to glucose is ~114 kcal/mol).

- Convert the incident light energy (in joules) based on photon flux and wavelength.

- Efficiency (%) = (Energy stored in biomass / Incident light energy) × 100.

- Dye-Based Electron Measurement (Alternative): As referenced from MIT research, inject a dye into chloroplasts and measure its color change as electrons are produced during photosynthesis as a proxy for energy conversion activity [22].

Key Considerations: The theoretical maximum efficiency for solar energy conversion in photosynthesis is approximately 11%, but actual overall efficiency in plants is typically 3-6% due to reflection, non-absorbed wavelengths, photorespiration, and other metabolic losses [21].

Energy Conversion Pathways and Experimental Workflows

The following diagrams illustrate the core energy conversion logic in biological molecular machines and a generalized experimental workflow for studying them.

Energy Inputs and Conversion in Biological Molecular Machines

Diagram 1: Energy inputs drive molecular machines via a proton motive force and ATP.

Generalized Workflow for Studying Molecular Machine Efficiency

Diagram 2: A generalized experimental workflow for efficiency studies.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents and Materials

This section details essential reagents and materials used in experimental studies of molecular machines, particularly those involving membrane-embedded systems like ATP synthases and ion pumps.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Machine Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Specific Example |

|---|---|---|

| Proteoliposomes | A synthetic lipid bilayer vesicle reconstituted with purified membrane proteins. Serves as a simplified, controlled model system for studying transport proteins and ATP synthases. | Soybean L-α-phosphatidylcholine (Type II-S), purified to remove contaminant K⁺ ions [23]. |

| Detergents | Amphipathic molecules used to solubilize membrane proteins from native membranes and keep them stable in solution during purification. | n-Octyl-β-d-glucoside, n-Decyl-β-d-maltoside [23]. |

| Ionophores | Lipid-soluble molecules that facilitate the transport of specific ions across biological membranes. Used to impose controlled membrane potentials. | Valinomycin (a K⁺-specific ionophore used to generate a diffusion potential) [23]. |

| Bio-Beads SM-2 | A hydrophobic adsorbent used to remove detergents from protein-lipid mixtures, facilitating the formation of sealed proteoliposomes. | Used in the reconstitution of thermophilic Bacillus PS3 ATP synthase [23]. |

| ATP Detection Kit | A coupled enzymatic assay (often based on luciferase) that produces light in proportion to ATP concentration. Essential for quantifying ATP synthesis or hydrolysis rates. | Luciferase-based luminescence assay [23]. |

| Inhibitory Domain Mutants | Engineered versions of proteins with regulatory domains removed to facilitate consistent, high activity in experimental assays. | TFoF1ϵΔc (ATP synthase with C-terminal inhibitory domain of ϵ subunit removed) [23]. |

The development of artificial molecular machines represents one of the most significant interdisciplinary achievements in modern science, bridging chemistry, materials science, and biomedical engineering. This field, which earned the 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for Jean-Pierre Sauvage, Sir J. Fraser Stoddart, and Bernard L. Feringa, has evolved from fundamental curiosity to a domain with profound practical applications [25] [26]. Rotaxanes—mechanically interlocked molecules consisting of a dumbbell-shaped axle threaded through a macrocyclic ring—have served as particularly promising platforms for creating functional molecular devices [27] [28]. Unlike conventional molecules held together by covalent bonds, rotaxanes maintain their structural integrity through mechanical bonds, enabling controlled molecular-level movements that can be harnessed to perform work [28] [29]. This review traces the historical evolution of rotaxane-based molecular machines, comparing their performance characteristics across development stages and against their natural counterparts, with special emphasis on their emerging applications in drug delivery, sensing, and molecular electronics.

Historical Timeline: Key Milestones in Molecular Machine Development

The conceptual foundation for molecular machinery was laid by physicist Richard Feynman in his visionary 1959 lecture "There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom," where he predicted tremendous potential in engineering at miniature scales [27] [29]. However, the practical realization of molecular machines followed a different trajectory than Feynman's top-down fabrication approach, evolving instead through bottom-up chemical synthesis and molecular design.

Table 1: Historical Evolution of Rotaxane-Based Molecular Machines

| Time Period | Key Development | Primary Innovators | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1960s-1970s | Early statistical synthesis of interlocked molecules | Various groups | Low-yield approaches; limited practical application |

| 1983 | First efficient template-directed synthesis of catenanes | Jean-Pierre Sauvage | Copper(I)-templated synthesis; 42% yield [26] [30] |

| 1991 | Development of functional rotaxanes | Fraser Stoddart | Introduction of electron-deficient stations and molecular shuttling [26] |

| 1994 | Controlled molecular motion in rotaxanes | Fraser Stoddart | Demonstrated precise control over ring positioning along axle [26] |

| 1999 | First unidirectional molecular motor | Ben Feringa | Light-driven motor with repetitive 360° rotation [26] |

| 2000s | Application-oriented prototypes | Multiple groups | Molecular lift (2004), artificial muscle (2005), nano-car (2011) [26] [30] |

| 2016 | Nobel Prize in Chemistry | Sauvage, Stoddart, Feringa | Recognition of molecular machine design and synthesis [25] |

| 2016-Present | Biomedical and electronic applications | Multiple groups | Drug delivery systems, molecular electronics, theranostic agents [27] [28] |

The following diagram illustrates the evolutionary pathway from fundamental discoveries to functional applications in rotaxane-based molecular machines:

Comparative Analysis: Engineered vs. Natural Molecular Machines

Natural systems exhibit remarkable molecular machines that have evolved over billions of years, including kinesin transport proteins, ATP synthase rotary motors, and bacterial flagella [11]. These biological machines operate with exceptional efficiency in aqueous environments, performing essential functions such as intracellular transport, energy conversion, and cell motility [31]. Inspired by these natural systems, researchers have developed artificial molecular machines with distinct operational characteristics and performance metrics.

Table 2: Performance Comparison: Natural vs. Engineered Molecular Machines

| Characteristic | Natural Molecular Machines | Early Synthetic Rotaxanes | Advanced Engineered Rotaxanes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Operating Environment | Aqueous biological milieus | Organic solvents [31] | Increasingly aqueous-compatible [28] [31] |

| Energy Source | ATP hydrolysis, proton gradients | Chemical, light, electrical stimuli [26] | Light, redox chemistry, enzymatic triggers [28] |

| Operational Speed | Microsecond to millisecond timescales | Seconds to hours [26] | Millisecond to second timescales (improved designs) [27] |

| Function | Specific biological processes | Molecular shuttling, switching [29] | Targeted drug delivery, mechanical actuation [28] |

| Efficiency | Highly optimized by evolution | Low to moderate | Moderate to high (device-dependent) [27] |

| Precision | Atomic-level precision | Molecular-level precision | Molecular-level precision with external control [26] |

| Integration | Naturally integrated in cellular systems | Isolved molecules in solution | Surface-bound, molecular arrays, polyrotaxanes [27] [28] |

The 2016 Nobel Prize: Recognizing Foundational Breakthroughs

The 2016 Nobel Prize in Chemistry celebrated three pivotal contributions that enabled the development of functional molecular machines. Jean-Pierre Sauvage's 1983 breakthrough introduced a copper(I)-templated synthesis that efficiently created mechanically interlocked catenanes—two interlocking ring-shaped molecules [25] [30]. This approach achieved an impressive 42% yield, dramatically surpassing previous statistical methods that typically yielded less than 1% [26]. This mechanical bond paradigm established the fundamental architecture for molecular machines.

Fraser Stoddart's 1991 development of rotaxanes introduced controlled linear motion at the molecular level [25] [26]. His design incorporated electron-rich and electron-deficient components that allowed a molecular ring to shuttle between distinct stations along a molecular axle. This molecular shuttle evolved into more sophisticated applications including a molecular lift capable of raising itself 0.7 nanometers, artificial muscles that could bend microscopic gold sheets, and molecule-based computer chips [26] [30].

Bernard Feringa contributed the first unidirectional molecular motor in 1999, overcoming the random thermal motion that typically dominates molecular movements [26]. His design incorporated molecular "rotor blades" that spun consistently in one direction when stimulated by successive pulses of ultraviolet light. Through iterative optimization, Feringa's team increased the rotation speed from slow cycles to an remarkable 12 million revolutions per second by 2014, and even demonstrated a molecular "nanocar" with four motors functioning as wheels [26].

Experimental Approaches and Methodologies

Synthesis and Characterization of Rotaxane Molecular Machines

The experimental protocols for creating and validating rotaxane-based molecular machines have evolved significantly since their inception. Early synthetic approaches relied on statistical methods, but modern template-directed strategies now achieve high yields through molecular recognition and self-assembly processes [29].

Template-Directed Synthesis Protocol:

- Molecular Recognition: Design complementary components with specific interaction sites (e.g., electron-rich and electron-deficient moieties) [26] [29]

- Threading: Facilitate the macrocycle to thread onto the axle molecule in solution through non-covalent interactions

- Capping Reaction: Introduce bulky stopper groups at the axle termini through covalent bond formation to prevent dethreading

- Purification: Isolate the interlocked structure using techniques such as column chromatography, HPLC, or precipitation

- Characterization: Verify structure using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy, mass spectrometry (MS), and X-ray crystallography [29]

Stimuli-Responsive Operation Protocol:

- Energy Input: Apply specific stimuli (light, chemical, electrochemical, or enzymatic) to trigger molecular motion [28]

- Motion Monitoring: Track changes using NMR, UV-Vis spectroscopy, or fluorescence measurements

- State Quantification: Measure switching yields, rotational speeds, or shuttling rates

- Function Verification: Confirm mechanical output (e.g., contraction, rotation, or molecular release) [28]

The following diagram illustrates the experimental workflow for creating and validating rotaxane-based molecular machines:

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Rotaxane-Based Molecular Machine Development

| Reagent/Material | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Cyclodextrins (α, β, γ) | Macrocyclic host components | Biocompatible rotaxanes for drug delivery [28] |

| Cucurbiturils | Synthetic macrocyclic hosts | High-affinity binding stations in rotaxanes [31] |

| Viologen (BIPY²⁺) derivatives | Electron-deficient stations | Molecular shuttles, redox-switchable rotaxanes [27] [31] |

| Tetrathiafulvalene (TTF) | Electron-rich station | Molecular switches with optical readout [29] |

| Phenanthroline ligands | Metal ion coordination sites | Copper(I)-templated catenane and rotaxane synthesis [29] |

| Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNPs) | Solid supports | Rotaxane-based drug delivery platforms [28] |

| Stoppers (e.g., trityl, adamantyl) | Bulky end groups | Preventing dethreading in rotaxane synthesis [29] |

Current Applications and Performance Data

Biomedical Applications: From Laboratory Curiosity to Therapeutic Promise

Rotaxane-based molecular machines have demonstrated remarkable potential in biomedical applications, particularly in targeted drug delivery and controlled release systems. Cyclodextrin-based rotaxanes have emerged as promising platforms due to their enhanced biocompatibility and FDA recognition of cyclodextrins as generally safe [28].

Drug Delivery Performance Metrics:

- Stimuli-Responsive Release: Enzyme-responsive rotaxane-based nanovalves on mesoporous silica nanoparticles demonstrated controlled doxorubicin release triggered by NAD(P)H:quinone oxidoreductase 1 (NQO1), an enzyme often overexpressed in tumor cells [28]

- Autophagy Induction: Methylated-β-cyclodextrin polyrotaxanes preferentially accumulate in the endoplasmic reticulum, inducing endoplasmic reticulum stress-mediated autophagic cell death, even in apoptosis-resistant malignant cells [28]

- Therapeutic Precision: Molecular motors activated by light can apply mechanical forces directly within cells, potentially reducing damage to normal tissues by eliminating the need for chemical agents that act from outside the cell [32]

Recent research has demonstrated that molecular motors with optimized rotation rates can effectively influence biological processes, with slower-rotating motors proving less effective at inducing cell death and calcium release [32]. This mechanical intervention at the cellular level represents a paradigm shift from conventional pharmacological approaches.

Molecular Electronics: Beyond Conventional Silicon Devices

Rotaxane-based molecular switches offer promising solutions for the growing challenges facing traditional semiconductor electronics as Moore's Law approaches physical limits [27]. These molecular devices can function as controllable switches with distinct "ON" and "OFF" states characterized by significant resistance differences.

Table 4: Performance Metrics of Rotaxane-Based Molecular Electronic Devices

| Device Characteristic | Performance Data | Comparative Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Switching Speed | Microsecond to millisecond range [27] | Sufficient for memory applications |

| Device Density | Theoretical > 10¹¹ devices/cm² [27] | ~100x improvement over current CMOS |

| Power Consumption | Significant reduction vs. semiconductor switches [27] | Enables ultra-low power electronics |

| Cycling Endurance | >10,000 cycles demonstrated in some systems [27] | Approaching commercial viability |

| Operating Voltage | Compatible with standard electronics (1-3V) [27] | Facilitates integration |

| Fabrication Cost | Potentially low through chemical synthesis [27] | Bottom-up self-assembly |

The development of rotaxane-based crossbar array architectures has demonstrated particular promise for creating reprogrammable molecular memory and logic systems. These architectures enable the construction of field-programmable gate arrays (FPGAs) at the molecular scale, with potential applications in ultra-dense memory storage and reconfigurable computing [27].

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The transition of rotaxane-based molecular machines from laboratory demonstrations to practical applications faces several significant challenges. For biomedical applications, improving aqueous compatibility remains a priority, as most artificial molecular machines still operate in organic solvents rather than the aqueous environments of biological systems [31]. Recent developments in aqueous artificial molecular pumps represent important steps toward bridging this gap [31].

In molecular electronics, device integration and stability under ambient conditions require further optimization. The development of robust anchoring chemistries for attaching molecular components to electrodes and protecting sensitive molecular states from environmental degradation are active research areas [27]. For both fields, scaling up production while maintaining precise control over molecular structure and function presents substantial synthetic challenges.

The remarkable progress in rotaxane-based molecular machines—from synthetic curiosities to functional devices—illustrates the rapidly advancing capabilities of molecular engineering. As researchers continue to address current limitations, these artificial molecular systems are poised to make increasingly significant contributions to biotechnology, medicine, and information technology, potentially revolutionizing how we approach diagnostics, therapeutics, and computing in the coming decades.

From Bench to Bedside: Methodologies and Therapeutic Applications in Drug Delivery and Gene Editing

The quest to build molecular machines presents a fundamental choice in design strategy: should we draw inspiration from the sophisticated blueprints provided by nature, or pursue the freedom of purely synthetic engineering? This comparison guide objectively evaluates three principal platform technologies that represent different answers to this question: biological DNA origami, synthetic organic chemistry, and integrated hybrid systems. Molecular machines are defined as nanoscale systems capable of consuming energy to produce controlled mechanical motion and perform useful work [33] [34]. In the biological realm, natural molecular machines like kinesin motors and ATP synthase demonstrate extraordinary capabilities, operating efficiently in the complex environment of the cell through mechanisms such as Brownian ratcheting, where energy is used to bias random thermal motion rather than oppose it directly [33]. The platforms discussed herein represent different approaches to mimicking, augmenting, or diverging from these biological paradigms, each with distinct performance characteristics, capabilities, and application potential for researchers and drug development professionals.

Technology Platform Comparison

The table below provides a systematic comparison of the three platform technologies across key performance metrics and characteristics relevant to molecular machine development.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Molecular Machine Platform Technologies

| Parameter | DNA Origami | Organic Synthesis | Hybrid Systems |

|---|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | ~0.34 nm (base-pair level) [35] | Atomic/Sub-atomic (bond-level) | Variable (component-dependent) |

| Structural Programmability | Exceptionally high via Watson-Crick pairing [36] [35] | Moderate (limited by synthetic pathways) | High (combines programmability of components) |

| Structural Addressability | Excellent (precise staple modification) [36] | Challenging (requires complex protecting strategies) | High (utilizes DNA addressability) |

| Material Diversity | Limited (primarily nucleic acids) | Extremely High (periodic table range) [37] | High (integrates multiple material classes) |

| Stimuli-Responsiveness | High (toehold-mediated strand displacement, ionic conditions) [38] [39] | Moderate (redox, light, pH) [33] | High (multiple orthogonal stimuli) |

| Environmental Operation | Aqueous buffers (compatible with physiological conditions) [35] | Varied (organic solvents to aqueous) | Primarily aqueous (buffer-dependent) |

| Throughput & Scalability | High (one-pot self-assembly) [35] | Low to Moderate (step-by-step synthesis) | Moderate (multi-step assembly) |

| Functional Versatility | Biosensing, drug delivery, nanophotonics [36] [40] | Molecular switches, motors, catalysts [33] | Synergistic functions (e.g., controlled permeation) [39] |

| Key Advantage | Precisely programmable nanostructures under mild conditions | Unmatched diversity of molecular structures and functions | Combines strengths of multiple material systems |

DNA Origami: Programmable Biological Nanofabrication

Technology Principles and Experimental Workflow

DNA origami technology utilizes the specific molecular recognition properties of DNA to create programmable nanostructures. The fundamental principle involves folding a long, single-stranded scaffold DNA (typically from the M13mp18 phage, ~7,000 bases) into precise shapes using hundreds of short synthetic "staple" strands [36]. This bottom-up self-assembly process occurs through Watson-Crick base pairing, where staple strands hybridize with specific regions of the scaffold, pulling it into the desired target structure [35]. The resulting nanostructures offer exceptional programmability, stability, and addressability, with the capacity to position functional components with nanometer precision [36].

A typical experimental workflow for creating 2D DNA origami structures involves several key stages [36] [35]:

- Sequence Design: The target shape is designed using computational tools like caDNAno [36]. The scaffold strand is routed through the shape, and complementary staple strands are designed to bind specific segments.

- Staple Preparation: Short staple strands (usually 20-60 nucleotides) are synthesized, purified, and mixed in a stoichiometric ratio with the scaffold strand.

- Thermal Annealing: The mixture is dissolved in an appropriate buffer (typically 1x TE with 10-20 mM MgCl₂) and subjected to a thermal annealing ramp (e.g., from 80°C to 20°C over several hours) to facilitate controlled hybridization and folding.

- Purification & Characterization: The assembled structures are purified from excess staples using techniques like gel electrophoresis or PEG precipitation, and characterized via Atomic Force Microscopy (AFM) or Transmission Electron Microscopy (TEM).

Figure 1: DNA Origami Fabrication Workflow

Performance Data and Applications

DNA origami excels in creating complex, dynamic nanostructures for biomedical applications. Recent advances include wireframe DNA origami capable of vertex-protruding transformation, enabling reconfigurable nanostructures that switch between open and closed forms via toehold-mediated strand displacement [38]. In drug delivery, DNA origami nanostructures (DONs) of 50-400 nm exploit the Enhanced Permeability and Retention (EPR) effect for tumor targeting, with frameworks like the DNA Soccer Framework (DSF) demonstrating enhanced cellular uptake and endosomal escape for siRNA delivery [35]. In biosensing, a supercharged DNA origami-based electrochemical sensor achieved an ultrasensitive detection limit of 0.26 fM for circulating tumor DNA by leveraging the structure's high negative charge to adsorb signal-amplifying electroactive molecules [40].

Organic Synthesis: The Synthetic Chemistry Approach

Technology Principles and Experimental Paradigms

Organic synthesis builds molecular machines through covalent bond formation, creating architectures like rotaxanes, catenanes, and molecular motors from first principles [33] [34]. This approach offers unparalleled freedom in molecular design, enabling the creation of structures not found in nature. The fundamental challenge lies in controlling the directionality of motion at the nanoscale, where Brownian motion dominates and inertial forces are negligible [33]. Synthetic molecular machines overcome this through ratchet mechanisms, where energy input (light, chemical, or electrochemical) creates a non-equilibrium state that biases random thermal fluctuations to produce directed motion [33] [34].

Key experimental paradigms include:

- Rotary Molecular Motors: Synthesis of overcrowded alkenes that undergo unidirectional, photochemically-induced rotary motion around the central double bond [34]. The synthesis involves creating chiral centers to break directional symmetry, ensuring rotation occurs in a single direction rather than random rocking.

- Linear Molecular Motors (Rotaxanes): Synthesis of interlocked structures where a molecular ring threads along a linear axle between different stations. Motion is typically driven by redox, light, or pH changes that alter the relative binding affinities of the stations [33]. This often requires template-directed synthesis and careful control of reaction kinetics.

- Molecular Pumps: Designing systems that use chemical fuel to drive the directional transport of rings onto molecular axles, creating a concentration gradient against equilibrium – a key demonstration of work performance [33].

Figure 2: Organic Synthesis Development Pathway

Performance Data and Applications

Synthetic molecular machines demonstrate remarkable capabilities when integrated into larger systems. When embedded in polymer networks, light-responsive molecular motors can cause macroscopic contraction of the material, translating nanoscale motion to macroscopic work [34]. Molecular switches based on rotaxanes have been organized on surfaces to create memory devices with densities exceeding conventional silicon-based electronics [33]. In catalysis, synthetic molecular machines have been designed to operate as processive catalysts, mimicking natural enzymes that remain attached to their polymeric substrates for multiple rounds of catalysis [33]. The key performance differentiator is the ability to create fundamentally new molecular architectures not constrained by biological building blocks, albeit with significant synthetic challenges in achieving the structural complexity routinely possible with DNA origami.

Hybrid Systems: Integrating Biological and Synthetic Paradigms

Technology Principles and Experimental Strategies

Hybrid molecular machine systems combine the programmability of DNA nanostructures with the functional diversity of synthetic chemistry, creating architectures that transcend the limitations of either approach alone [41]. This integration creates systems where DNA provides the structural framework and addressability, while synthetic components introduce new physical properties and functionalities. The core design principle involves conjugating synthetic molecules to DNA strands at specific locations on DNA tiles or origami structures, enabling higher-order assembly and function guided by orthogonal interactions beyond Watson-Crick base pairing [41].

Key experimental strategies include:

- Hydrophobicity-Guided Assembly: Conjugating small hydrophobic molecules (e.g., dendritic alkyl chains, pyrene, tetraphenylethylene) to single-stranded DNA, which are then incorporated into DNA nanostructures. The hydrophobic interactions drive the controlled hierarchical assembly of DNA building blocks into larger superstructures [41].

- Membrane-Interfacing Systems: Engineering DNA origami structures functionalized with cholesterol anchors that embed in lipid bilayers. These "DNA nanorafts" can be designed to reconfigure their shape in response to molecular signals, enabling programmable remodeling of synthetic cell membranes and even formation of transmembrane channels [39].

- Signal-Responsive Nanodevices: Creating DNA-origami-based systems that undergo large-scale conformational changes in response to specific triggers. For instance, reconfigurable DNA nanorafts have been demonstrated to transition between square (70.8 nm × 55 nm) and elongated rectangular (190 nm × 20 nm) forms with an aspect ratio change from 1.3 to 9.5, driven by toehold-mediated strand displacement [39].

Performance Data and Applications

Hybrid systems demonstrate emergent capabilities not possible with either component alone. In one groundbreaking application, DNA nanorafts functionalized with 12 cholesterol anchors were shown to collectively undergo reversible transitions between disordered and locally ordered states on giant unilamellar vesicle (GUV) membranes [39]. This reconfiguration generated sufficient steric pressure to programmably remodel GUV morphology at the microscale – a dramatic example of nanoscale motion amplifying to macroscopic effects. Most strikingly, during membrane shape recovery, these collectively ordered DNA rafts cooperated with biogenic pores (OmpF) to perforate the membrane, creating sealable synthetic channels that enabled transport of large cargo (up to ~70 kDa) across the membrane [39]. This represents a functional capability approaching that of natural membrane machinery, achieved through hybrid design.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The table below catalogues essential reagents and materials used across the featured molecular machine platforms, with their specific functions in research and development.

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Machine Development

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application | Platform |

|---|---|---|

| M13mp18 Phage DNA | Long single-stranded scaffold for DNA origami assembly [36] | DNA Origami |

| Synthetic Staple Strands | Short DNA oligonucleotides (20-60 nt) for folding scaffold [36] [35] | DNA Origami |

| Magnesium Chloride (MgCl₂) | Critical cation for stabilizing DNA origami structures in buffer [36] [39] | DNA Origami, Hybrid |

| Toehold Strands | DNA sequences enabling strand displacement for dynamic reconfiguration [38] [39] | DNA Origami, Hybrid |

| Cholesterol-TEG Oligos | Membrane anchoring of DNA nanostructures via lipid insertion [39] | Hybrid Systems |

| DBCO-N₃ Chemistry | Bioorthogonal conjugation of synthetic molecules to DNA via SPAAC [41] | Hybrid Systems |

| Hydrophobic Probes (HB1-HB5) | Programmable hydrophobic units guiding DNA assembly [41] | Hybrid Systems |

| Giant Unilamellar Vesicles (GUVs) | Synthetic cell models for testing membrane-machine interactions [39] | Hybrid Systems |

| Overcrowded Alkenes | Molecular backbones for light-driven rotary motors [34] | Organic Synthesis |

| Template Molecules | Structural directing agents for interlocked molecule synthesis [33] | Organic Synthesis |

The pursuit of precision in drug delivery has catalyzed the development of sophisticated nanoscale systems capable of controlling the release of therapeutic agents. Among these, two engineered platforms stand out: synthetic rotaxane-based actuators and mesoporous silica nanoparticles (MSNs). These systems represent a paradigm shift from natural molecular machines, offering unparalleled synthetic tunability and controlled functionality. Rotaxanes, as mechanically interlocked molecules, utilize a unique "push-from-within" release mechanism, while MSNs provide a high-surface-area scaffold for cargo encapsulation. This guide provides a detailed, objective comparison of these technologies, equipping researchers with the experimental data and protocols needed to evaluate their respective applications in advanced drug delivery systems.

The following table provides a direct comparison of the core characteristics, performance metrics, and application landscapes of rotaxane actuators and mesoporous silica nanoparticles.

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Rotaxane Actuators and Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles for Drug Delivery

| Feature | Rotaxane Actuators | Mesoporous Silica Nanoparticles (MSNs) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Structure | Interlocked architecture with a macrocycle on a stoppered axle [42] | Inorganic silica matrix with 2-50 nm pore diameter [43] [44] |

| Release Mechanism | Force-controlled sequential release via mechanochemical scission (e.g., retro Diels-Alder) [42] | Diffusion-controlled, often gated with stimuli-responsive "gatekeepers" [43] [28] |

| Drug Loading Capacity | Defined, stoichiometric loading (e.g., up to 5 cargo molecules per rotaxane) [42] | High, tunable capacity based on pore volume and surface area (700-1300 m²/g) [43] [44] |

| Release Efficiency | 71% (solution, ultrasonication); 30% (bulk, compression) [42] | Varies widely with functionalization; enhanced release in acidic pH (e.g., for cancer therapy) [43] [45] |

| Stimuli Responsiveness | Mechanical force (ultrasonication, compression) [42] | pH, enzymes, redox potential, light, magnetic field [43] [28] |

| Key Advantage | Programmable, multi-cargo release from a single molecular event [42] [46] | Excellent biocompatibility (GRAS status), high stability, and facile functionalization [43] [44] |

| Primary Challenge | Complex synthesis and integration into macroscopic materials [42] | Potential for premature drug release without advanced gating strategies [43] |

| Demonstrated Cargos | Doxorubicin, fluorescent tags, organocatalysts [42] | Ibuprofen, anticancer drugs (Doxorubicin), antibiotics, proteins [43] [44] [45] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Rotaxane-Based Force-Controlled Release

The mechanochemical release using rotaxane actuators is a precise process, as detailed in recent nature research [42].

1. Synthesis of Macromolecular Rotaxane:

- Objective: To create a chain-centered rotaxane structure where the interlocked component is positioned to experience maximal mechanical force.

- Procedure:

- Assembly: Form an inclusion complex between a pillar[5]arene (P5) macrocycle and a C12 alkyl chain axle.

- Stoppering: Cap the axle with a 3,5-bis(trifluoromethyl)benzenesulfonyl (BTBS) group, creating an activated rotaxane precursor.

- Functionalization: Substitute the BTBS group with a pre-synthesized cargo compartment oligomer (bearing furan moieties) via a stopper-exchange reaction.

- Polymerization: Initiate Single-Electron Transfer Living Radical Polymerization (SET-LRP) of methyl acrylate from both the macrocycle and the axle of the rotaxane initiator. This yields a polymer chain (e.g., Poly(Methyl Acrylate), PMA) with the rotaxane at its center, crucial for efficient mechanochemical activation [42].

- Cargo Loading: Attach maleimide-functionalized cargo molecules (e.g., drug, fluorophore) to the furan moieties on the cargo compartment via a Diels-Alder reaction [42].

2. Mechanical Activation and Release:

- Objective: To activate the rotaxane actuator and quantify cargo release.

- Procedure:

- Activation: Subject a dilute solution of the cargo-loaded rotaxane polymer to ultrasonication. The collapsing cavitation bubbles in the solvent generate elongational flow fields that stretch the polymer chain.

- Mechanism: This force pulls the macrocycle along the axle into the cargo compartment. The macrocycle forcefully contacts the sterically bulky Diels-Alder adducts, triggering a retro Diels-Alder reaction that cleaves the covalent bond and releases the cargo molecule [42].

- Monitoring: Track reaction progress using Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) to observe polymer scission. Quantify cargo release efficiency via 1H NMR spectroscopy by comparing the integration of diagnostic peaks of the Diels-Alder adduct versus the revealed furan unit after sonication [42].

- Cargo Recovery: Extract the post-sonication polymer residue with methanol to isolate and recover the released small molecules for further analysis [42].

MSN-Based Stimuli-Responsive Delivery