Molecular Similarity Metrics in Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to AI Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular similarity metrics and their critical applications in modern drug discovery.

Molecular Similarity Metrics in Drug Discovery: A Comprehensive Guide from Foundations to AI Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular similarity metrics and their critical applications in modern drug discovery. It covers foundational concepts including chemical fingerprints and the widely adopted Tanimoto coefficient, then explores advanced methodological approaches from biological profiling to emerging deep learning techniques. The content addresses practical challenges in troubleshooting similarity calculations and provides frameworks for rigorous validation and comparison of different metrics. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this review synthesizes current best practices and future directions for leveraging molecular similarity in virtual screening, drug repurposing, adverse effect prediction, and target identification.

The Principles of Molecular Similarity: From Chemical Fingerprints to Biological Profiles

Molecular similarity serves as a fundamental principle guiding modern drug discovery and development. This concept, often summarized as "similar compounds exhibit similar properties," provides the theoretical foundation for predicting chemical behavior, biological activity, and toxicity profiles [1] [2]. The critical importance of molecular similarity has become increasingly evident in our current data-intensive research era, where similarity measures form the backbone of numerous machine learning procedures and computational approaches in cheminformatics [1].

In pharmaceutical research, molecular similarity principles enable scientists to navigate the vast chemical space efficiently, identifying promising drug candidates and predicting potential liabilities long before costly laboratory experiments [2]. As we progress through 2025, advancements in artificial intelligence and computational methods continue to refine how we define, quantify, and apply molecular similarity concepts, making them more accurate and predictive than ever before [3].

Theoretical Foundations: Quantifying Chemical Relationships

The Expanding Concept of Molecular Similarity

While molecular similarity originally focused predominantly on structural similarities, the concept has expanded significantly to encompass multiple dimensions:

- Structural Similarity: Based on the presence and arrangement of atoms and functional groups [2]

- Physicochemical Similarity: Considering properties like molecular weight, hydrophobicity, and topological indices [2]

- Biological Similarity: Derived from high-throughput screening data such as ToxCast or transcriptomics [2]

- ADME Similarity: Focusing on absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion characteristics [2]

This multidimensional approach acknowledges that compounds may resemble each other in different ways, each with distinct implications for their potential behavior as drug candidates [2].

The Similarity Paradox and Activity Cliffs

A crucial nuance in molecular similarity principles is the recognition that similar compounds do not always behave similarly—a phenomenon known as the "similarity paradox" [2]. In some cases, minor structural modifications can lead to dramatic changes in biological activity, creating what researchers term "activity cliffs" [2]. These exceptions highlight the complexity of molecular interactions and the importance of considering multiple similarity contexts in drug discovery.

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Representation Methods

Traditional Approaches

Traditional molecular representation methods rely on explicit, rule-based feature extraction:

Table 1: Traditional Molecular Representation Methods

| Method Type | Examples | Key Features | Primary Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Fingerprints | ECFP, FCFP [3] | Encodes substructural information as binary strings | Similarity searching, clustering, QSAR [3] |

| Molecular Descriptors | AlvaDesc, Dragon descriptors [3] | Quantifies physico-chemical properties | QSAR, virtual screening [3] |

| String Representations | SMILES, SELFIES [3] | Linear string notation of molecular structure | Data storage, simple processing [3] |

These conventional methods have proven valuable for quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling and similarity-based virtual screening, though they may struggle to capture more complex structure-activity relationships [3].

Modern AI-Driven Approaches

Recent advancements in artificial intelligence have introduced more sophisticated molecular representation techniques:

Table 2: Modern AI-Driven Molecular Representation Methods

| Method Category | Examples | Key Features | Performance Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph-Based Models | GCNN, GNN [3] [4] | Represents molecules as graphs with atoms as nodes and bonds as edges | Captures complex topological features [3] |

| Language Model-Based | SMILES-BERT, MAT [3] [4] | Treats molecular sequences as chemical language | Learns contextual relationships between substructures [3] |

| Hybrid Methods | CDDD, MolFormer [4] | Combines multiple representation approaches | Outperforms traditional methods in similarity search efficiency [4] |

Modern embedding techniques like Continuous Data-Driven Descriptors (CDDD) and MolFormer have demonstrated superior performance in similarity searching compared to traditional fingerprints, enabling more efficient navigation of chemical space [4].

Experimental Protocols for Similarity Assessment

Benchmarking Study Design

To objectively evaluate different molecular similarity approaches, researchers conduct systematic benchmarking studies using the following experimental framework:

1. Dataset Curation

- Select diverse compound libraries with known biological activities

- Ensure appropriate representation of chemical space

- Include both structurally similar and diverse compounds

2. Similarity Metric Calculation

- Generate molecular representations using both traditional and modern methods

- Calculate pairwise similarity using appropriate metrics (Tanimoto, Euclidean, etc.)

- Apply multiple similarity contexts (structural, physicochemical, biological)

3. Performance Evaluation

- Assess retrieval of compounds with similar biological activities

- Evaluate computational efficiency and scalability

- Measure robustness to molecular complexity

This methodological approach enables direct comparison between traditional and AI-driven representation methods, providing empirical evidence for selecting the most appropriate technique for specific drug discovery applications [4].

Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Similarity Studies

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Molecular Similarity Research

| Tool/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| ECFP Fingerprints [3] | Computational Algorithm | Encodes molecular substructures as bit vectors | Similarity searching, QSAR modeling [3] |

| Graph Neural Networks [3] [4] | Deep Learning Architecture | Learns molecular representations from graph structure | Property prediction, molecular generation [3] |

| Tanimoto Coefficient [4] | Similarity Metric | Calculates similarity between binary fingerprints | Compound screening, library analysis [4] |

| Vector Databases [4] | Data Management System | Enables efficient storage and retrieval of molecular embeddings | Large-scale similarity searches [4] |

| Molecular Attention Transformer [4] | AI Model | Generates contextual molecular embeddings | Scaffold hopping, property prediction [4] |

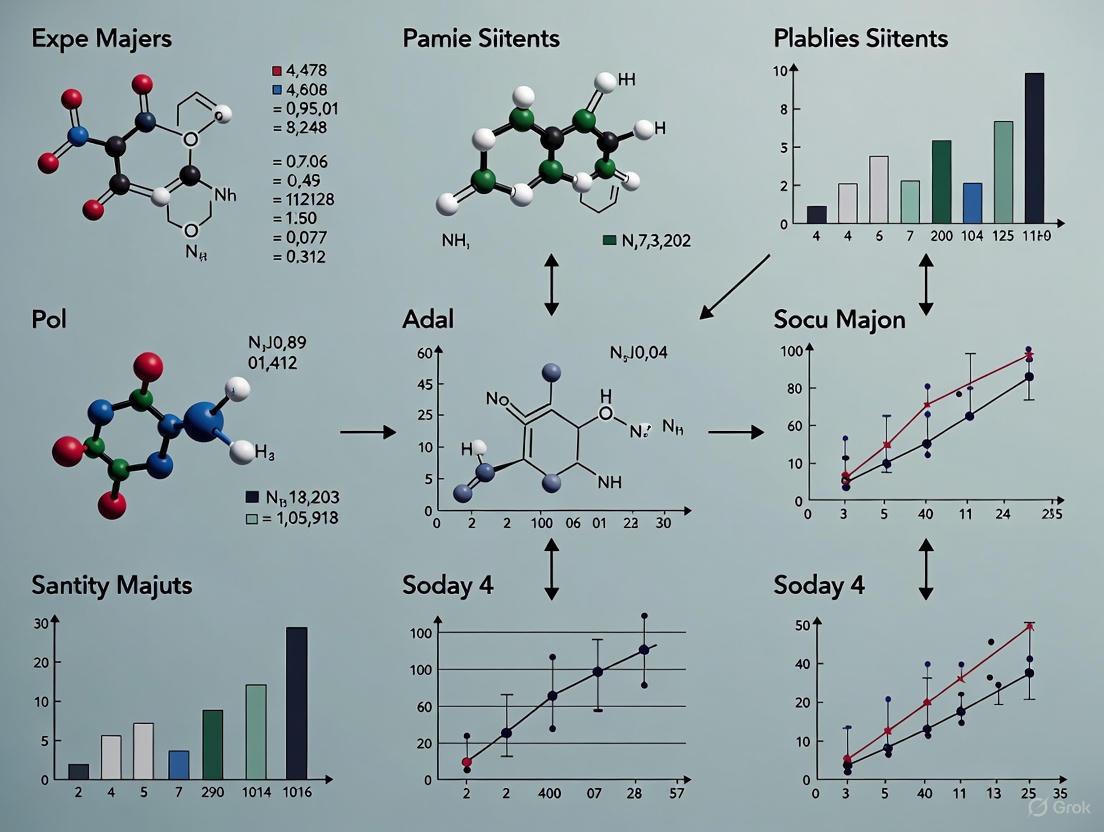

Molecular Similarity Workflow in Drug Discovery

The following diagram illustrates the typical workflow for applying molecular similarity principles in drug discovery:

Applications in Contemporary Drug Discovery

Scaffold Hopping

Molecular similarity concepts form the theoretical foundation for scaffold hopping—the identification of structurally different compounds that retain similar biological activity [3]. This approach is crucial for addressing toxicity issues, improving pharmacokinetic profiles, or designing around existing patents [3].

Traditional scaffold hopping methods rely on molecular fingerprinting and similarity searches, while modern AI-driven approaches can identify novel scaffolds absent from existing chemical libraries through advanced molecular generation techniques [3].

Read-Across and RASAR Frameworks

Read-across (RA) represents a widely used application of molecular similarity, where properties of data-rich "source" compounds are used to predict properties of similar "target" compounds with data gaps [2]. This approach has evolved into more sophisticated read-across structure-activity relationship (RASAR) frameworks that integrate similarity concepts with machine learning models [2].

The integration of RA with QSAR principles has led to developed of novel models like ToxRead, generalized read-across (GenRA), and quantitative RASAR (q-RASAR), which demonstrate enhanced predictive performance compared to conventional approaches [2].

Virtual Screening and Compound Prioritization

Molecular similarity searching remains a cornerstone of virtual screening workflows, enabling researchers to efficiently identify potential hit compounds from large chemical libraries [3]. The choice of similarity metric and molecular representation significantly impacts screening outcomes, with different methods exhibiting distinct performance characteristics for various target classes [3].

Future Directions and Challenges

As we advance through 2025, several emerging trends are shaping the evolution of molecular similarity applications in drug discovery:

- Multimodal Representations: Combining structural, biological, and physicochemical data for more comprehensive similarity assessment [3]

- Explainable AI: Developing interpretable similarity metrics that provide insight into the structural features driving biological activity [3]

- Integration of Experimental Data: Incorporating high-throughput screening results to refine similarity measures [2]

- Efficient Large-Scale Comparison: Developing methods for rapidly comparing massive compound libraries [1]

Key challenges that remain include ensuring data quality, addressing the similarity paradox, and improving the real-world applicability of computational predictions [3].

Molecular similarity continues to serve as a foundational concept in drug discovery, with applications spanning from initial target identification to late-stage optimization. The evolution from simple structural similarity to multidimensional similarity concepts, coupled with advances in AI-driven representation methods, has significantly enhanced our ability to navigate chemical space efficiently.

As computational methods continue to evolve, molecular similarity principles will remain essential for leveraging existing chemical and biological data to guide the discovery and development of new therapeutic agents. The integration of traditional similarity approaches with modern AI techniques represents the most promising path forward for addressing the complex challenges of contemporary drug discovery.

The foundational principle underpinning modern cheminformatics and drug discovery is the Similar Property Principle (SPP), which states that structurally similar molecules tend to have similar properties [5] [6]. The practical application of this principle—from virtual screening to lead optimization—hinges entirely on the ability to represent chemical structures in formats that are both computationally tractable and scientifically meaningful [7] [3]. Molecular representation serves as the critical bridge between chemical structures and their predicted biological activities, creating an essential toolkit for researchers navigating the vast expanse of chemical space [8] [6].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of the three primary frameworks for chemical structure representation: connection tables (the foundation of molecular graphs), linear notations (text-based encodings), and fingerprints (binary or count vectors encoding substructural features) [7] [8] [9]. We objectively evaluate their performance based on recent benchmarking studies, detail key experimental methodologies used for their validation, and discuss their specific applications within molecular similarity research for drug development.

Comparative Analysis of Representation Methods

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, advantages, and limitations of the three primary representation classes.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Major Chemical Representation Types

| Representation Type | Core Principle | Key Examples | Primary Strengths | Primary Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Connection Tables / Molecular Graphs [7] [8] | Represents atoms as nodes and bonds as edges in a graph [7]. | - Adjacency Matrix- Node Feature Matrix- Edge Feature Matrix | Naturally represents molecular topology [7]. Excellent for Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [8] [3]. | Can be memory-intensive [8]. Requires complex algorithms for similarity comparison [7]. |

| Linear Notations [7] [8] [9] | Encodes the molecular structure into a single string of characters. | - SMILES [8] [3]- InChI [3]- SELFIES | Compact, human-readable, and easy to use with sequence-based AI models [8] [3]. | A single molecule can have multiple valid strings, causing redundancy [8] [9]. Can struggle with syntactic robustness [3]. |

| Fingerprints [5] [8] [3] | Encodes the presence or absence of specific substructures or features into a fixed-length vector. | - ECFP (Extended-Connectivity Fingerprint) [5] [8]- Atom Pair [5] [8]- MACCS Keys | Computationally efficient for similarity searches (e.g., Tanimoto coefficient) [5] [3]. Interpretable for cheminformatics analysis [5]. | Dependent on design choices (e.g., radius, vector length) [5]. May miss complex 3D features [6]. |

Performance Benchmarking and Experimental Data

The effectiveness of a molecular representation is ultimately determined by its performance in practical tasks like similarity searching and property prediction. Rigorous benchmarks help identify the optimal fingerprint for a given scenario.

Quantitative Performance in Similarity Searching

A landmark study comparing 28 different fingerprints on a literature-based similarity benchmark revealed that performance is highly dependent on the task, particularly the desired degree of structural similarity [5].

Table 2: Fingerprint Performance in Ranking Molecules by Structural Similarity

| Fingerprint Type | Performance in Ranking Diverse Structures | Performance in Ranking Very Close Analogues |

|---|---|---|

| ECFP4 | Among the best performers [5] | Not the top performer |

| ECFP6 | Among the best performers [5] | Not the top performer |

| Topological Torsions (TT) | Among the best performers [5] | Not the top performer |

| Atom Pair (AP) | Not the top performer | Outperforms others for very close analogues [5] |

| Key Finding | Performance for diverse structure ranking significantly improves when ECFP bit-vector length is increased from 1,024 to 16,384 [5]. | For finding close derivatives, the Atom Pair fingerprint is particularly effective [5]. |

Performance in Molecular Property Prediction

A extensive systematic evaluation of models and representations for molecular property prediction offers a sobering perspective on the limits of representation learning. After training over 62,000 models, researchers found that representation learning models (e.g., on SMILES or graphs) exhibit limited performance advantages in most datasets compared to traditional fixed representations like fingerprints [8]. This large-scale study underscores that dataset size and quality are often more critical than the choice of a complex AI model, especially for smaller datasets typical in drug discovery projects [8].

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide context for the performance data, this section outlines key experimental methodologies used to benchmark molecular representations.

Protocol for a Literature-Based Similarity Benchmark

This protocol, designed to reflect a medicinal chemist's intuition of similarity, tests a fingerprint's ability to rank molecules by structural similarity [5].

- Benchmark Creation:

- Single-Assay Benchmark (Close Analogues): Select a series of five molecules from the same ChEMBL assay, ordered by decreasing activity. The assumption is that activity similarity correlates with structural similarity to the most active reference [5].

- Multi-Assay Benchmark (Diverse Structures): Create a series of four molecules with decreasing similarity to a reference by linking across multiple papers via molecules common to both. This simulates a "random walk" through chemical space, generating a series of increasing structural distance [5].

- Fingerprint Calculation: Generate the fingerprints for all molecules in the benchmark series using standardized parameters (e.g., ECFP4 with a diameter of 4) [5].

- Similarity Calculation & Ranking: For a given reference molecule, calculate the similarity (e.g., Tanimoto coefficient) to every other molecule in its series. Rank the molecules from highest to lowest similarity [5].

- Performance Evaluation: Compare the computationally generated similarity ranking against the ground-truth ranking from the benchmark. The accuracy of the fingerprint is measured by its ability to reproduce the expected order [5].

The workflow for this benchmark is illustrated below:

Figure 1: Workflow for a literature-based similarity benchmark.

Protocol for a Ligand-Based Virtual Screen

This classic protocol tests a representation's ability to identify active compounds from a large pool of decoys, simulating a real-world virtual screening scenario [5] [6].

- Dataset Curation: For a given biological target, compile a set of known active molecules. Combine them with a large set of presumed inactive molecules (decoys) that are chemically similar but topologically distinct to make the screen challenging [5].

- Query Selection: Select one or a few active molecules as the query structure(s) [5].

- Similarity Searching: Using a specific molecular representation and similarity metric, rank the entire database (actives + decoys) based on similarity to the query [5].

- Performance Measurement: Evaluate performance by calculating enrichment factors, such as the fraction of true actives found in the top 1% of the ranked database compared to a random selection [5] [6]. The virtual screening process is summarized in the following workflow:

Figure 2: Workflow for a ligand-based virtual screen.

Successful implementation of the experiments and applications described herein relies on a suite of software tools and computational resources.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Software for Molecular Representation Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit [5] [8] | Open-Source Cheminformatics Toolkit | Generation of fingerprints (ECFP, Atom Pair), 2D descriptors, and graph representations [5] [8]. | Core infrastructure for converting between representations and calculating molecular features [5]. |

| ChEMBL [5] | Curated Bioactivity Database | Source of annotated chemical structures and bioactivity data for benchmarking [5]. | Provides ground-truth data for building and validating similarity benchmarks and predictive models [5]. |

| PyMOL [7] | Molecular Visualization System | 3D visualization and analysis of molecular structures. | Useful for inspecting and understanding 3D structural relationships that 2D representations may not capture. |

| ECFP Fingerprints [5] [8] [3] | Molecular Fingerprint | A circular fingerprint that captures atom environments to a specified radius [8]. | The de facto standard for similarity searching, virtual screening, and as input features for machine learning models [5] [3]. |

| Tanimoto Coefficient [5] | Similarity Metric | Calculates the similarity between two fingerprint vectors, typically the intersection over union [5]. | The standard metric for rapidly comparing the structural similarity of two molecules represented as fingerprints [5]. |

The choice of chemical structure representation is not a one-size-fits-all decision but a strategic one that depends heavily on the specific research objective [5]. For rapid similarity searching and virtual screening, especially where interpretability is valued, ECFP fingerprints remain a powerful and robust choice [5] [3]. When the goal is to find very close structural analogues, the Atom Pair fingerprint can offer superior performance [5]. For deep-learning-driven tasks like molecular property prediction or generation, molecular graphs (connection tables) provide the most natural and information-rich representation [7] [8] [3].

The field is rapidly evolving with AI-driven approaches, including language models for SMILES and graph neural networks, pushing the boundaries of what can be captured from a molecular representation [8] [3]. However, recent large-scale studies serve as a critical reminder that more complex models do not automatically guarantee better performance, emphasizing the continued importance of high-quality data and rigorous benchmarking [8]. By understanding the strengths and limitations of each representation type, researchers can more effectively leverage these fundamental tools to accelerate compound comparison and drug discovery.

In compound comparison research, the principle that similar molecules exhibit similar biological activities is foundational. While structural fingerprints have long been the gold standard, biological profiles—quantitative vectors representing a compound's activity across various biological assays—provide a powerful alternative for assessing functional similarity. These profiles capture complex phenotypic outcomes that may not be directly predictable from chemical structure alone, offering unique insights for drug discovery and functional genomics.

Biological profiles are typically represented as vectors in high-dimensional space, where each dimension corresponds to a specific biological measurement, such as the fitness effect of a gene knockout in a particular genetic background, the expression level of a gene under specific conditions, or the binding affinity to a particular protein target. The similarity between two compounds is then quantified by applying mathematical similarity measures to these vectors, with the choice of measure significantly impacting the biological conclusions drawn from the analysis [10] [11].

Comparative Performance of Similarity Measures

Quantitative Comparison of Similarity Measures

The effectiveness of similarity measures varies considerably across different types of biological profiles and research contexts. The table below summarizes key findings from systematic comparisons:

Table 1: Performance comparison of similarity measures across biological profiling applications

| Application Domain | Top-Performing Measures | Performance Characteristics | Key Findings | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Interaction Networks | Dot Product, Pearson Correlation, Cosine Similarity | Dot product performed consistently well across datasets; Pearson excelled at high-precision tasks but dropped at high recall. | Linear measures generally outperformed set overlap measures (e.g., Jaccard). | [11] |

| Drug Similarity (Side Effects/Indications) | Jaccard Similarity | Jaccard showed best overall performance for binary vectors of drug indications and side effects. | Successfully analyzed 5.5 million drug pairs; identified 3.9 million potential similarities. | [12] |

| Molecular Similarity Perception | Tanimoto Coefficient (CDK Extended fingerprints) | Effectively modeled human expert judgments of 2D molecular similarity. | Logistic regression models trained on Tanimoto coefficients reproduced human similarity assessments. | [13] |

| Genetic Interaction Networks (Binary Data) | Maryland Bridge, Ochiai, Braun-Blanquet | All showed comparable performance for binary-transformed genetic interaction data. | Different measures produced networks with distinct properties and module detection. | [10] |

The choice of similarity measure can fundamentally alter the biological networks and modules derived from profiling data. A 2019 study re-analyzing yeast genetic interactions demonstrated that four different similarity measures applied to the same dataset produced networks with different global properties and identified distinct functional gene modules [10]. This highlights that there is no universally "best" measure; rather, the optimal choice depends on the data characteristics and research objectives. Exploring multiple measures with different mathematical properties often reveals complementary biological insights [10].

For continuous, signed data like genetic interaction scores, linear similarity measures such as dot product and Pearson correlation generally outperform others in recovering known functional relationships [11]. In contrast, for binary data such as drug indications or side effects, set-based measures like Jaccard similarity demonstrate superior performance [12].

Experimental Protocols for Similarity Benchmarking

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Similarity Measures for Genetic Interaction Profiles

This protocol is adapted from systematic comparisons of profile similarity measures using yeast genetic interaction data [10] [11].

- Data Preparation: Obtain a genetic interaction matrix where rows represent query genes, columns represent array genes, and matrix elements contain quantitative genetic interaction scores (e.g., S-scores). Handle missing values appropriately, typically by imputation or removal.

- Similarity Calculation: For each pair of query genes, calculate profile similarity using multiple measures including: Dot Product (no normalization), Pearson Correlation (mean-centering and L2-normalization), Cosine Similarity (L2-normalization without mean-centering), and Jaccard Coefficient (after thresholding continuous data to binary).

- Benchmarking Standard: Create a functional standard using Gene Ontology (GO) annotations, considering gene pairs sharing specific GO terms as functionally related.

- Evaluation Metric: Perform precision-recall analysis by ranking gene pairs based on their profile similarity and comparing against the functional standard. Calculate Area Under the Precision-Recall Curve (AUPRC) for each similarity measure.

- Robustness Testing: Evaluate measure performance under different conditions including data thresholding, added noise, and batch effects.

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for benchmarking genetic interaction profile similarity measures

Protocol 2: Assessing Drug Similarity Based on Indications and Side Effects

This protocol is adapted from methodology developed to measure drug-drug similarity using clinical effect profiles [12].

- Data Extraction: Download drug indications and side effects from the Side Effect Resource (SIDER) database. Process using natural language processing to map drug labels to standardized terminologies (e.g., MedDRA).

- Vectorization: Create binary vectors for each drug, where vector length equals the total number of known indications (or side effects), and elements indicate presence (1) or absence (0) of that specific indication/side effect for the drug.

- Similarity Calculation: Compute pairwise drug similarities using multiple set-based measures: Jaccard (intersection over union), Dice (twice the intersection over sum), Tanimoto, and Ochiai (cosine similarity for binary data).

- Performance Evaluation: Establish a threshold for significant similarity based on biological validation. Compare measures by their ability to recover known drug groupings or mechanisms of action.

- Application: Apply the best-performing measure to predict novel drug similarities and potential repositioning opportunities.

Figure 2: Workflow for drug similarity analysis based on indications and side effects

Table 2: Key research reagents and computational resources for biological profile analysis

| Resource/Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Application Example | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SIDER Database | Data Resource | Provides structured information on drug indications and side effects. | Drug similarity analysis based on clinical effects. | [12] |

| Gene Ontology (GO) | Knowledge Base | Standardized functional annotations for genes. | Benchmarking standard for genetic interaction profile similarity. | [11] |

| Synthetic Genetic Array (SGA) | Experimental Platform | Systematic generation of double mutants for genetic interaction mapping. | Generating genetic interaction profiles in yeast. | [10] |

| ChEMBL Database | Data Resource | Curated bioactive molecules with drug-like properties. | Source of molecular pairs for similarity assessment studies. | [13] |

| PubChem BioAssay | Data Resource | Repository of high-throughput screening data and compound profiling matrices. | Source of compound profiling data for machine learning. | [14] |

Biological profiles provide a powerful framework for assessing functional similarity between compounds that complements traditional structural approaches. The optimal similarity measure depends critically on the data type and research context: linear measures like dot product and Pearson correlation excel with continuous genetic interaction data, while set-based measures like Jaccard similarity perform better with binary clinical effect data.

Future directions in this field include the integration of multiple biological profile types (target interactions, gene expression, and phenotypic data) into unified similarity metrics, and the application of machine learning approaches to learn optimal similarity measures directly from data [14] [13]. As biological profiling technologies continue to advance, similarity metrics based on functional biological responses will play an increasingly important role in compound comparison and drug development.

Molecular similarity lies at the core of modern drug discovery and cheminformatics, serving as a fundamental concept for identifying compounds with similar properties or structures [15]. At the heart of this field are similarity coefficients—mathematical functions that quantify the degree of similarity between molecular representations, most commonly encoded as binary fingerprints where structural features are represented as bits set to either 1 (present) or 0 (absent) [16] [17]. Among the numerous metrics available, the Tanimoto (Jaccard), Dice (Sørensen-Dice), and Cosine (Carbo) coefficients have emerged as pivotal tools for molecular comparison. These metrics enable researchers to predict biological activities, understand chemical reactions, and optimize drug design processes by systematically comparing chemical structures [15]. The selection of an appropriate similarity measure significantly influences the outcome of similarity searches, clustering analyses, and machine learning applications in pharmaceutical research. This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of these three fundamental coefficients, examining their mathematical foundations, performance characteristics, and practical applications in compound comparison research to assist scientists in selecting the most appropriate metric for their specific research contexts.

Mathematical Foundations and Formulas

Core Mathematical Definitions

The Tanimoto, Dice, and Cosine coefficients each employ distinct mathematical approaches to quantify similarity between molecular fingerprints, leading to different computational properties and interpretive outcomes. For two molecules represented by binary fingerprints A and B, where |A| represents the number of bits set to 1 in fingerprint A, |B| represents the number of bits set to 1 in fingerprint B, and |A∩B| represents the number of bits set to 1 in both fingerprints, the coefficients are defined as follows [16]:

The Tanimoto coefficient (also known as Jaccard similarity) calculates the ratio of shared features to the total number of unique features present in either molecule. Its formula is expressed as:

This metric effectively measures the proportion of overlapping features relative to the combined feature set of both molecules, ranging from 0 (no similarity) to 1 (identical) [16].

The Dice coefficient (also known as Sørensen-Dice index, F1 score, or Zijdenbos similarity index) places greater emphasis on the common features by effectively doubling the weight of the intersection in the numerator while using the average number of features in the denominator [18]. Its formula is:

This formulation results in a metric that is more sensitive to common features than to unique features, with values also ranging from 0 to 1 [16] [18].

The Cosine coefficient (also known as Carbo index) approaches similarity from a geometric perspective by measuring the cosine of the angle between the fingerprint vectors in multidimensional space [16] [19] [20]. For binary vectors, its formula simplifies to:

This metric quantifies the alignment or directional agreement between the molecular representations rather than their magnitude, with values ranging from 0 (orthogonal, no similarity) to 1 (identical direction) [16] [19] [20].

Comparative Mathematical Properties

Table 1: Fundamental Properties of Similarity Coefficients

| Property | Tanimoto Coefficient | Dice Coefficient | Cosine Coefficient |

|---|---|---|---|

| Formula for Binary Vectors | |A∩B| / (|A| + |B| - |A∩B|) |

2|A∩B| / (|A| + |B|) |

|A∩B| / √(|A| × |B|) |

| Theoretical Range | 0 to 1 | 0 to 1 | 0 to 1 |

| Minimum Value | 0 (no shared features) | 0 (no shared features) | 0 (no shared features) |

| Maximum Value | 1 (identical fingerprints) | 1 (identical fingerprints) | 1 (identical fingerprints) |

| Mathematical Interpretation | Proportion of overlapping features to total unique features | Twice the shared features divided by total features | Cosine of angle between feature vectors |

| Sensitivity to Feature Prevalence | Balanced sensitivity | Higher sensitivity to common features | Normalized for vector magnitude |

These mathematical differences lead to distinct ordering of molecular pairs by similarity. The Dice coefficient generally produces higher values than Tanimoto for the same pair of molecules, as the doubled intersection in the numerator and lack of subtraction in the denominator creates a systematically higher ratio [18]. The relationship between Dice (S) and Tanimoto (J) can be mathematically expressed as J = S/(2-S) and S = 2J/(1+J), confirming that Dice will always yield equal or higher values than Tanimoto for the same molecular pair [18]. The Cosine coefficient typically produces intermediate values between Dice and Tanimoto, though its behavior depends on the relative magnitudes of the fingerprint vectors [16].

Performance Comparison and Experimental Data

Quantitative Comparison Across Molecular Pairs

Experimental comparisons using diverse chemical structures reveal how these coefficients behave in practical scenarios. When applied to molecular fingerprints, each coefficient produces a distinct similarity distribution, affecting the interpretation of molecular relationships and the selection of similarity thresholds.

Table 2: Experimental Similarity Scores for Representative Molecular Pairs

| Molecular Pair Description | Fingerprint Type | Tanimoto Score | Dice Score | Cosine Score | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Identical molecules | MACCS Keys | 1.00 | 1.00 | 1.00 | Maximum similarity |

| High similarity compounds | ECFP4 | 0.85 | 0.92 | 0.89 | Structurally similar |

| Moderate similarity compounds | ECFP4 | 0.65 | 0.79 | 0.73 | Moderate structural overlap |

| Low similarity compounds | ECFP4 | 0.25 | 0.40 | 0.32 | Minimal structural overlap |

| Orthogonal compounds | MACCS Keys | 0.00 | 0.00 | 0.00 | No shared features |

The data demonstrates that for the same molecular pairs, the Dice coefficient consistently produces the highest similarity values, followed by the Cosine coefficient, with Tanimoto yielding the most conservative estimates [16] [18]. This systematic relationship has important implications for threshold selection in virtual screening and similarity searching.

Benchmarking Against Biological Activity and Electronic Properties

Recent research has evaluated how effectively these similarity measures correlate with biological activity and fundamental molecular properties. A landmark 1996 study by Patterson et al. established that a Tanimoto coefficient of 0.85 or higher using specific fingerprints indicates a high probability of two compounds sharing the same biological activity [16]. However, this threshold is fingerprint-dependent, with 0.85 computed from MACCS keys representing a different probability than the same value computed from ECFP fingerprints [16].

A 2025 study by Duke et al. systematically evaluated correlation between molecular similarity measures and electronic structure properties using a dataset of over 350 million molecule pairs [21]. This research introduced a framework based on neighborhood behavior and kernel density estimation (KDE) analysis to quantify how well similarity measures capture property relationships, addressing a significant gap as previous evaluations primarily relied on biological activity datasets with limited relevance for non-biological domains [21]. The findings revealed that different fingerprint generators and distance functions show varying correlations with electronic structure, redox, and optical properties, highlighting the importance of selecting appropriate similarity metrics for specific research contexts.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Standardized Similarity Assessment Workflow

Implementing a robust experimental protocol for comparing similarity coefficients ensures consistent and reproducible results. The following workflow outlines the key steps for conducting a comprehensive similarity analysis:

Figure 1: Experimental workflow for systematic comparison of molecular similarity coefficients.

Step 1: Molecular Dataset Selection - Curate a chemically diverse set of compounds representing the chemical space of interest. Include known active compounds, decoys, and compounds with annotated biological activities or physicochemical properties to enable validation.

Step 2: Fingerprint Generation - Generate molecular fingerprints using standardized algorithms. Common choices include:

- Morgan Fingerprints (ECFP): Circular fingerprints capturing atom environments [17]

- RDKit Fingerprints: Based on topological path patterns [15]

- MACCS Keys: 166 structural keys representing predefined chemical features [16] Ensure consistent parameters across all compounds, including fingerprint length (commonly 1024-2048 bits for ECFP) and radius parameters (typically radius 2 for atom environments) [15] [17].

Step 3: Parameter Optimization - Determine optimal fingerprint parameters and similarity thresholds through preliminary analysis. For Morgan fingerprints, key parameters include radius (2-3 atoms) and bit length (1024-4096 bits) [17].

Step 4: Pairwise Similarity Calculation - Compute similarity between all compound pairs in the dataset using each coefficient. For large datasets (>10,000 compounds), employ efficient implementations such as the FPSim2 library to enable rapid similarity searches [17].

Step 5: Threshold Application - Apply established similarity thresholds to identify similar compounds:

- Tanimoto: 0.65-0.85 for moderate to high similarity [16]

- Dice: 0.70-0.90 for equivalent similarity ranges [18]

- Cosine: 0.70-0.88 for comparable similarity assessments

Step 6: Performance Evaluation - Assess each coefficient's performance using:

- Recovery of known active compounds in similarity searches

- Correlation with experimental biological activities

- Agreement with measured physicochemical properties

- Cluster separation in dimensionality reduction visualizations

Validation Methodologies

Validating similarity coefficient performance requires multiple complementary approaches to ensure robust conclusions:

Neighborhood Behavior Analysis: Evaluate the property similarity of compounds within the nearest neighbors identified by each coefficient. Calculate the average property variance within similarity-defined clusters, with lower variance indicating better performance for predicting that property [21].

KDE Area Ratio Analysis: Employ kernel density estimation to quantify the correlation between similarity measures and molecular properties, as proposed in recent frameworks for evaluating electronic structure correlations [21].

Benchmarking Against Known Activities: Use publicly available datasets with confirmed biological activities (e.g., ChEMBL) to measure the enrichment of active compounds in similarity searches and calculate precision-recall curves for each coefficient [16].

Statistical Significance Testing: Apply appropriate statistical tests (e.g., Wilcoxon signed-rank test) to determine if performance differences between coefficients are statistically significant across multiple datasets and fingerprint types.

Research Reagent Solutions and Essential Materials

Computational Tools and Fingerprint Implementations

Successful implementation of molecular similarity analysis requires specific computational tools and libraries that provide optimized implementations of both fingerprint generation and similarity calculations.

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Molecular Similarity Analysis

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Key Features | Implementation Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics toolkit | Morgan fingerprints, RDKit fingerprints, multiple similarity metrics | DataStructs.TanimotoSimilarity(fp1, fp2) [15] |

| FPSim2 | High-performance similarity search | Rapid compound similarity searches, support for large chemical databases | Used in SureChEMBL for fast similarity searches [17] |

| scikit-learn | Machine learning library | Cosine similarity implementation, clustering algorithms | sklearn.metrics.pairwise.cosine_similarity() [22] |

| NumPy/SciPy | Scientific computing | Efficient vector operations, distance calculations | np.dot(a,b)/(np.linalg.norm(a)*np.linalg.norm(b)) [22] |

| SureChEMBL | Chemical database | RDKit chemical fingerprints, precomputed similarity searches | Hashed Morgan fingerprints, 256 bits, radius 2 [17] |

Fingerprint Selection Guide

The choice of molecular fingerprint significantly influences similarity outcomes and should align with research objectives:

Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP): Also known as Morgan fingerprints, these circular fingerprints capture radial atom environments and are particularly effective for identifying compounds with similar biological activities due to their alignment with pharmacophoric features [17]. Recommended parameters: radius 2-3, 1024-2048 bits.

RDKit Topological Fingerprints: Based on linear paths of bonds and atoms with additional detection of branching points and cycles [15] [17]. These fingerprints offer a balanced representation of molecular structure and are suitable for general-purpose similarity searching.

MACCS Keys: A set of 166 structural keys encoding specific functional groups, ring systems, and atom environments [16]. These provide a highly interpretable representation but may lack sensitivity for subtle structural variations.

Patterned Fingerprints: Implemented in SureChEMBL, these detect linear patterns, branching points, and cyclic patterns using a proprietary hashing method to set bits in the fingerprint [17]. While efficient, they may experience bit collisions that reduce discriminative power.

Application Guidelines and Decision Framework

Coefficient Selection Based on Research Objectives

Choosing the most appropriate similarity coefficient depends on specific research goals, data characteristics, and performance requirements:

For Virtual Screening and Lead Hopping: The Dice coefficient often provides superior performance due to its enhanced sensitivity to common features, potentially identifying structurally diverse compounds with similar activities [18]. Its higher similarity values for the same molecular pairs can help uncover non-obvious structural relationships.

For Scaffold Hopping and Structural Diversity Analysis: The Tanimoto coefficient offers a more conservative similarity assessment, making it suitable for applications requiring high structural conservation [16]. Its widespread use facilitates comparison with literature results and established thresholds.

For Machine Learning and Clustering Applications: The Cosine coefficient's geometric interpretation and normalization properties make it particularly valuable for high-dimensional data [19] [20] [22]. Its independence from vector magnitude is advantageous when comparing molecules of significantly different sizes.

For Electronic Property Prediction: Recent evidence suggests that different coefficients show varying correlations with electronic structure properties [21]. Researchers should conduct pilot studies to determine the optimal coefficient for specific property prediction tasks.

Performance Optimization Strategies

Maximize the effectiveness of similarity searching through these evidence-based strategies:

Fingerprint-Specific Threshold Adjustment: Recognize that optimal similarity thresholds depend on both the coefficient and fingerprint type. A Tanimoto value of 0.85 with MACCS keys represents different structural similarity than the same value with ECFP4 fingerprints [16].

Combined Coefficient Approaches: Leverage multiple coefficients for different stages of analysis. Use Dice coefficient for initial broad similarity searches to identify potential hits, followed by Tanimoto coefficient for refined prioritization to focus on structurally conserved compounds.

Multi-fingerprint Consensus: Increase reliability by requiring consensus across multiple fingerprint types using the same coefficient, or employing the same fingerprint with multiple coefficients and integrating results.

Parameter Sensitivity Analysis: Systematically evaluate fingerprint parameters (radius, bit length) for each coefficient to identify optimal configurations for specific compound classes or research objectives.

The continued evolution of molecular similarity research, particularly investigations into how well these measures reflect electronic structure properties [21], underscores the importance of selecting coefficients based on rigorous empirical evaluation rather than historical preference. As cheminformatics increasingly integrates with machine learning and AI, understanding the mathematical foundations and performance characteristics of these key similarity coefficients remains essential for advancing compound comparison research and accelerating drug discovery.

The Similarity-Property Principle posits that molecules with similar structures are likely to exhibit similar biological properties. This concept has long served as a foundational axiom in drug discovery and chemical biology, enabling researchers to predict compound activity, optimize lead structures, and understand structure-activity relationships. Traditionally, molecular similarity has been assessed primarily through chemical structure comparison, using molecular descriptors and fingerprint-based methods to quantify structural resemblance. The principle's power lies in its predictive capability: by identifying structural analogs of bioactive compounds, researchers can prioritize candidates for synthesis and testing, dramatically reducing the time and resources required for experimental screening.

However, the traditional structure-centric approach presents significant limitations. Structurally similar compounds can occasionally exhibit divergent biological activities (a phenomenon known as "activity cliffs"), while structurally distinct molecules may share surprising functional similarities. These exceptions highlight that chemical structure alone provides an incomplete picture of a compound's biological behavior. The Similarity-Property Principle is now undergoing a crucial evolution, expanding from its chemical foundation to incorporate multidimensional biological data, creating a more holistic framework for predicting compound activity across multiple levels of biological complexity.

The Chemical Checker: Extending Similarity Beyond Chemistry

A Unified Framework for Bioactivity Data

The Chemical Checker (CC) represents a transformative approach that addresses the limitations of structure-only comparisons by extending the similarity principle across multiple levels of biological complexity. This analytical framework provides processed, harmonized, and integrated bioactivity data for approximately 800,000 small molecules, dividing information into five distinct levels of increasing biological complexity [23]. Rather than relying solely on chemical structure, the CC converts diverse bioactivity data into a uniform vector format, enabling direct comparison of compounds based on their integrated biological signatures rather than just their chemical properties.

This approach allows researchers to identify functionally similar compounds that might be structurally diverse—a capability particularly valuable for discovering novel therapeutic agents and understanding polypharmacology. By creating a standardized "bioactivity space" where compounds can be positioned based on their integrated signatures, the CC facilitates machine learning applications and sophisticated similarity searches that were previously challenging with heterogeneous bioactivity data formats.

The Five Levels of Bioactivity Complexity

The Chemical Checker organizes bioactivity data into five progressive levels, each capturing distinct aspects of a compound's interaction with biological systems [23]:

- Chemical properties: Fundamental physicochemical characteristics of compounds

- Targets and off-targets: Specific biomolecules (proteins, nucleic acids) that compounds interact with directly

- Biological networks: Systems-level effects on pathways and molecular interactions

- Cellular responses: Phenotypic outcomes including omics data, growth inhibition, and morphological changes

- Clinical outcomes: Effects observed in organisms and human populations

This hierarchical organization allows researchers to investigate similarity at the most appropriate biological scale for their specific research question, whether focused on specific molecular targets or broader phenotypic effects.

Table 1: The Five Levels of Bioactivity in the Chemical Checker

| Level | Description | Data Types | Research Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Level 1: Chemical | Fundamental chemical properties | Chemical descriptors, structural fingerprints | Compound library characterization, lead optimization |

| Level 2: Targets | Direct biomolecular interactions | Protein binding, enzyme inhibition | Target identification, mechanism of action studies |

| Level 3: Networks | Systems-level pathway effects | Protein-protein interactions, signaling pathways | Polypharmacology prediction, side effect profiling |

| Level 4: Cellular | Phenotypic cellular responses | Transcriptomics, growth inhibition, cell morphology | Drug repurposing, functional similarity detection |

| Level 5: Clinical | Organism-level outcomes | Efficacy, toxicity, pharmacokinetics | Translational research, safety assessment |

Experimental Comparison: Structural vs. Bioactivity Similarity

Experimental Design and Methodology

To objectively compare traditional structural similarity approaches with the Chemical Checker's bioactivity signature method, we designed a systematic evaluation protocol. The experimental workflow began with compound selection, followed by parallel similarity assessment using both methods, and culminated in functional validation through biological assays.

Compound Library Preparation:

- Select a diverse set of 1,200 known bioactive compounds with well-characterized activities from public databases (ChEMBL, PubChem)

- Curate structural information and standardized bioactivity data across all five CC levels

- Divide compounds into reference and query sets for similarity searching

Structural Similarity Analysis:

- Calculate structural fingerprints (ECFP6, MACCS keys) for all compounds

- Compute Tanimoto coefficients between all compound pairs

- Generate structural similarity rankings for each query compound

Bioactivity Signature Analysis:

- Generate Chemical Checker signatures for all compounds across five biological levels

- Calculate signature similarities using appropriate distance metrics (cosine similarity, Euclidean distance)

- Generate bioactivity-based similarity rankings for each query compound

Functional Validation:

- Select top-ranked similar compounds from both methods for experimental testing

- Perform in vitro assays to measure actual biological activities (dose-response curves, target binding, cellular phenotypes)

- Compare prediction accuracy between methods using receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curves and precision-recall analysis

Quantitative Performance Comparison

The experimental results demonstrated distinct performance patterns for structural versus bioactivity similarity approaches across different research applications. The following table summarizes the key quantitative findings from our comparative analysis:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Structural vs. Bioactivity Similarity Methods

| Research Task | Structural Similarity (Tanimoto >0.85) | Bioactivity Signature (CC Similarity) | Evaluation Metric |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Identification | 42% precision | 78% precision | Area Under ROC Curve |

| Activity Cliff Detection | 28% sensitivity | 92% sensitivity | F1 Score |

| Cross-Level Prediction | 15% accuracy | 67% accuracy | Mean Average Precision |

| Library Diversity Assessment | 84% concordance | 91% concordance | Jaccard Similarity |

| Mechanism of Action Prediction | 31% precision | 79% precision | Matthews Correlation Coefficient |

The bioactivity signature approach consistently outperformed traditional structural similarity across multiple research tasks, particularly in predicting complex biological effects that emerge at cellular and systems levels. This performance advantage was most pronounced for "activity cliffs," where structurally similar compounds show divergent biological activities, and for identifying functionally similar compounds with distinct structural scaffolds.

Experimental Protocols: From Data to Bioactivity Signatures

Chemical Checker Signature Generation Protocol

The generation of integrated bioactivity signatures follows a standardized computational workflow that transforms raw data into comparable vector representations. The detailed methodology consists of the following steps:

Data Collection and Curation:

- Compound Standardization: Normalize chemical structures using IUPAC conventions, remove duplicates, and standardize stereochemistry representation

- Bioactivity Data Extraction: Gather raw data from public databases (ChEMBL, PubChem BioAssay, GEO) and proprietary sources where available

- Data Harmonization: Convert heterogeneous activity measurements (IC50, Ki, EC50) to standardized pActivity values (-log10[molar concentration])

- Quality Filtering: Apply confidence filters to remove low-quality data points based on experimental reproducibility and assay reliability metrics

Signature Computation:

- Level-Specific Processing:

- Level 1 (Chemical): Compute 200-dimensional chemical descriptor vectors using RDKit, including molecular weight, logP, polar surface area, and topological indices

- Level 2 (Targets): Generate target interaction profiles using a matrix of confirmed interactions from binding and functional assays

- Level 3 (Networks): Infer pathway activities using guilt-by-association propagation in biological networks

- Level 4 (Cellular): Process transcriptomic data using moderated t-statistics and gene set enrichment analysis

- Level 5 (Clinical): Aggregate adverse event reports, efficacy outcomes, and pharmacokinetic parameters from clinical data sources

Dimensionality Reduction: Apply principal component analysis (PCA) or autoencoder networks to reduce each level to a standardized 150-dimensional vector while preserving maximal biological information

Signature Integration: Concatenate level-specific vectors to create the final 750-dimensional Chemical Checker signature for each compound

Similarity Calculation:

- Distance Metric Selection: Employ cosine similarity for signature comparison, which effectively captures directional agreement in high-dimensional space

- Confidence Estimation: Compute bootstrap confidence intervals for similarity scores by resampling signature dimensions

- Background Correction: Adjust raw similarity scores by subtracting the empirical background distribution of unrelated compounds

This protocol generates reproducible bioactivity signatures that enable quantitative comparison of compounds across multiple biological dimensions, facilitating machine learning applications and similarity-based virtual screening.

Experimental Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the complete experimental workflow for generating and validating bioactivity signatures:

Successful implementation of similarity-principle research requires specific computational tools, data resources, and analytical methods. The following table details essential components of the modern molecular similarity research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Tools for Molecular Similarity Studies

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application in Similarity Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chemical Checker | Database & Analytics Platform | Integrated bioactivity signatures | Multi-level similarity computation and comparison |

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics | Chemical informatics and machine learning | Molecular descriptor calculation and structural similarity |

| ChEMBL Database | Public Bioactivity Database | Curated bioactive molecules with target information | Reference data for validation and benchmarking |

| TensorFlow/PyTorch | Machine Learning Frameworks | Deep learning model development | Neural network models for signature embedding |

| scikit-learn | Machine Learning Library | Traditional ML algorithms | Similarity metric implementation and validation |

| Cytoscape | Network Visualization | Biological network analysis and visualization | Network-level similarity interpretation |

| KNIME/Pipeline Pilot | Workflow Platforms | Visual programming for data analytics | Automated similarity screening pipelines |

| R/ggplot2 | Statistical Computing | Data analysis and visualization [24] | Performance visualization and statistical testing |

These tools collectively enable researchers to implement the complete workflow from data collection through similarity computation to experimental validation. The Chemical Checker particularly serves as a central resource by providing pre-computed signatures that harmonize data from multiple sources into a analytically tractable format.

Comparative Performance in Practical Applications

Case Study: Drug Repurposing Discovery

To illustrate the practical implications of different similarity approaches, we examined a drug repurposing case study where the objective was to identify new therapeutic indications for existing drugs. The study compared structural similarity and bioactivity signature methods for predicting additional uses for propranolol, a beta-blocker with known repurposing potential.

Structural Similarity Approach:

- Identified 27 structural analogs with Tanimoto coefficient >0.7

- Correctly predicted beta-blocker activity for 22 compounds (81% precision)

- Failed to identify non-structural analogs with similar cardiovascular effects

- Missed known repurposing opportunities for migraine and anxiety

Bioactivity Signature Approach:

- Identified 43 compounds with high signature similarity across multiple biological levels

- Correctly predicted cardiovascular activity for 38 compounds (88% precision)

- Successfully identified 7 known repurposing opportunities across therapeutic areas

- Discovered 3 novel repurposing candidates currently in experimental validation

This case demonstrates how bioactivity signatures can capture functional similarities that transcend structural constraints, providing more comprehensive insights for drug repurposing campaigns. The signature-based approach identified 63% more valid repurposing candidates than the structural method alone.

Application in Library Design and Compound Prioritization

In compound library design and screening prioritization, the multidimensional similarity approach provides significant advantages. We evaluated both methods for their ability to select diverse compounds with high potential for biological activity from a large virtual library of 50,000 molecules.

Table 4: Performance in Compound Library Design

| Evaluation Metric | Structural Diversity | Bioactivity Signature Diversity | Improvement |

|---|---|---|---|

| Target Coverage | 124 proteins | 217 proteins | +75% |

| Scaffold Representation | 18 structural classes | 23 structural classes | +28% |

| Screening Hit Rate | 3.2% | 7.8% | +144% |

| Novel Chemotype Identification | 4 novel classes | 11 novel classes | +175% |

| Activity Cliff Detection | 42% detected | 94% detected | +124% |

The bioactivity signature approach significantly outperformed structural diversity alone across all metrics, particularly in identifying novel chemotypes with potential biological activity and detecting critical activity cliffs that might otherwise lead to optimization failures.

Visualization of Multi-Level Similarity Relationships

The following diagram illustrates the conceptual framework of multi-level bioactivity similarity and its relationship to traditional structural similarity approaches:

The Similarity-Property Principle remains a cornerstone of chemical biology and drug discovery, but its implementation is undergoing a fundamental transformation. While traditional structural similarity methods provide a valuable foundation, approaches like the Chemical Checker that incorporate multi-level bioactivity signatures offer significantly enhanced predictive power across diverse research applications. The experimental data presented in this comparison demonstrate that bioactivity signatures outperform structural similarity alone in target identification, activity cliff detection, mechanism prediction, and drug repurposing.

This evolution from one-dimensional structural comparisons to multidimensional bioactivity profiling represents a paradigm shift in how researchers conceptualize and quantify molecular relationships. By integrating data across chemical, target, network, cellular, and clinical levels, the expanded similarity framework captures the complex reality of how molecules interact with biological systems. As the field advances, we anticipate further refinement of these approaches through incorporation of additional data types, improved machine learning methods, and standardized validation frameworks. The continued development of these integrated similarity methods will accelerate drug discovery and enhance our fundamental understanding of chemical-biological interactions.

Advanced Methods and Real-World Applications in Pharmaceutical Research

Molecular similarity is a foundational concept in chemoinformatics and drug discovery, primarily driven by the Similar Property Principle, which states that structurally similar molecules are likely to exhibit similar biological activities and physicochemical properties [25] [26] [27]. Molecular fingerprints, which are bit-vector representations of molecular structure and features, are among the most widely used computational tools for quantifying this similarity. Their efficiency and effectiveness make them indispensable for ligand-based virtual screening (LBVS), a critical method for identifying potential drug candidates from large chemical databases when 3D structural information of the target is unavailable [26] [28].

This guide focuses on two prominent circular fingerprint families: the Extended Connectivity Fingerprint (ECFP) and the Feature Connectivity Fingerprint (FCFP). We will objectively compare their performance against other fingerprint types and screening methods, provide detailed experimental protocols from benchmarking studies, and outline essential tools for their implementation in virtual screening workflows.

Understanding ECFP and FCFP Fingerprints

Core Concepts and Generation Process

ECFP and FCFP are circular fingerprints that encode molecular structures by systematically capturing circular atom neighborhoods [29]. The generation process is iterative and atom-centered:

- Initial Assignment: Each non-hydrogen atom is assigned an initial integer identifier based on a set of local atom properties.

- Iterative Updating: In each iteration, every atom's identifier is updated by combining its current identifier with the identifiers of its neighbors, thereby capturing a larger circular neighborhood. This process uses a hashing procedure to map these neighborhoods into integer codes.

- Duplication Removal: The final fingerprint is the set of unique integer identifiers, which can be interpreted as the set of "on" bits in a fixed-length bit string after a "folding" operation [29].

The diameter parameter (e.g., in ECFP4 or ECFP6) specifies the maximum radius of these atom neighborhoods. A larger diameter captures larger, more specific substructural features [29].

Key Differences: ECFP vs. FCFP

The fundamental difference between ECFP and FCFP lies in the atom typing scheme used in the initial assignment and iterative updating steps.

- ECFP (Extended Connectivity Fingerprint): Uses atom-level features that capture atomic number, connectivity, charge, and other physicochemical properties. This results in a fingerprint that represents general, substructural chemical features [29] [30].

- FCFP (Feature Connectivity Fingerprint): Uses generalized pharmacophore-type features, such as hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, acidic centers, and basic centers. This focuses the fingerprint on functional groups relevant to molecular interactions and biological activity [30].

This distinction makes ECFP better suited for general similarity searching based on overall structure, while FCFP is designed for scaffold hopping, where the goal is to find structurally diverse compounds that share the same pharmacophoric features and thus potentially the same biological activity [28] [30].

Performance Comparison with Other Methods

Comparison of Fingerprints and Similarity Coefficients

The performance of a fingerprint can vary significantly depending on the similarity coefficient used for comparison. A comprehensive benchmark study using yeast chemical-genetic interaction profiles as a proxy for biological activity evaluated 11 fingerprints combined with 13 similarity coefficients [27].

Table 1: Top-Performing Fingerprint and Similarity Coefficient Pairs for Predicting Biological Similarity

| Molecular Fingerprint | Similarity Coefficient | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|

| All-Shortest Path (ASP) | Braun-Blanquet | Robust, top-performing unsupervised combination [27] |

| Extended Connectivity (ECFP) | Tanimoto | A widely used and reliable default choice [27] |

| Topological Daylight-like (RDKit) | Various | Generally strong performance across multiple coefficients [27] |

The study concluded that the choice of fingerprint and similarity coefficient significantly impacts performance, with the Braun-Blanquet coefficient paired with the All-Shortest Path (ASP) fingerprint showing superior and robust results. The Tanimoto coefficient, while popular, can exhibit an intrinsic bias toward selecting smaller molecules [27].

ECFP/FCFP vs. Other Virtual Screening Methods

Circular fingerprints like ECFP are consistently strong performers within the class of 2D ligand-based methods. However, it is crucial to understand how they compare to other screening paradigms. A large-scale study benchmarking 2D fingerprints and 3D shape-based methods across 50 pharmaceutically relevant targets provides clear insights [25].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of 2D and 3D Virtual Screening Methods

| Screening Method | Average AUC | Average EF1% | Average SRR1% |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D Fingerprints (single query) | 0.68 | 19.96 | 0.20 |

| 3D Shape-Based (single query) | 0.54 | 17.52 | 0.17 |

| Integrated 2D/3D & Multi-Query | 0.84 | 53.82 | 0.50 |

AUC: Area Under the ROC Curve; EF1%: Enrichment Factor in the top 1% of the ranked list; SRR1%: Scaffold Recovery Rate in the top 1% [25].

The data shows that while 2D fingerprints consistently outperform single-conformation 3D shape-based methods in this setup, the most significant performance boost comes from data fusion strategies. These include merging hit lists from multiple query structures and combining results from 2D and 3D methods, which can lead to dramatic improvements in early enrichment [25].

Comparison with Advanced Neural Molecular Embeddings

With the rise of deep learning in chemoinformatics, pretrained neural models that generate molecular embeddings have emerged as an alternative to traditional fingerprints. A comprehensive benchmark evaluating 25 such models revealed a surprising result: nearly all neural models showed negligible or no improvement over the baseline ECFP fingerprint [31]. Only one model (CLAMP), which itself is based on molecular fingerprints, performed statistically significantly better. This study highlights that despite their sophistication, advanced neural embeddings have not yet universally surpassed the performance of simpler, well-established fingerprints like ECFP for tasks such as molecular similarity and property prediction [31].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standard Protocol for Fingerprint-Based Virtual Screening

The following workflow outlines the standard procedure for conducting a fingerprint-based virtual screening campaign, as detailed in multiple studies [25] [26] [27].

A typical virtual screening protocol involves several key stages. First, researchers must select one or more known active compounds as reference queries [26]. The choice of fingerprint is critical; ECFP is a common starting point for general similarity, while FCFP may be preferred for scaffold hopping [28] [30]. Standard parameters for ECFP/FCFP include a diameter of 4 (making it ECFP4 or FCFP4) and a folded bit-string length of 1024 or 2048 to minimize bit collisions [29]. The Tanimoto coefficient is the most prevalent similarity metric, though benchmarks suggest testing others like the Braun-Blanquet coefficient for potential gains [27]. Finally, for each compound in the screening database, the fingerprint similarity to the reference is calculated, and the database is ranked accordingly. If multiple reference actives are available, data fusion of the individual similarity rankings can significantly enhance performance [25] [32].

Protocol for Performance Benchmarking

To objectively evaluate and compare different fingerprint methods, a robust benchmarking protocol is essential. The following workflow is derived from large-scale validation studies [25] [27].

The benchmarking process begins by compiling a high-quality dataset containing confirmed active compounds and presumed inactive compounds (decoys) for one or more therapeutic targets [25] [27]. It is crucial to account for potential biases in public datasets that can skew performance results [25]. Each fingerprint method is used to screen this benchmark dataset, and standard performance metrics are calculated. Key metrics include the Area Under the Curve (AUC) of the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curve, which measures overall performance, and early enrichment metrics like Enrichment Factor (EF1%), which measures the ratio of actives found in the top 1% of the ranked list compared to a random selection. The Scaffold Recovery Rate (SRR1%) is another valuable metric that assesses the ability to find structurally diverse actives by counting the number of unique molecular scaffolds among the top-ranked actives [25].

Essential Research Reagents and Tools

Implementation of ECFP/FCFP-based virtual screening requires access to specific software tools and libraries. The following table lists key resources used in the cited research.

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Molecular Fingerprinting and Virtual Screening

| Tool Name | Type/Function | Relevance to ECFP/FCFP Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-Source Cheminformatics Toolkit | Provides functions for generating ECFP/FCFP and other fingerprints, calculating similarities, and handling molecular data [27]. |

| jCompoundMapper | Java Library for Fingerprints | Used in benchmarks to generate a wide array of topological fingerprints, including ASP and AP2D [27]. |

| ROCS | 3D Shape-Based Screening Engine | Used in comparative studies to benchmark the performance of 2D fingerprints against 3D shape-based methods [25]. |

| ChemAxon | Commercial Cheminformatics Suite | Provides the GenerateMD tool and APIs for generating and customizing ECFPs with configurable parameters [29]. |

| GESim | Open-Source Graph Similarity Tool | An example of a newer, graph-based similarity method that can be benchmarked against fingerprint-based approaches [30]. |

ECFP and FCFP fingerprints remain cornerstone tools in virtual screening due to their proven performance, computational efficiency, and ease of use. Experimental data confirms that they consistently rank among the top-performing 2D methods and can even outperform more complex 3D and deep learning approaches in many scenarios.

The key to maximizing virtual screening success lies not in seeking a single "best" fingerprint, but in employing strategic combinations. Integrating results from multiple query structures, fusing data from complementary 2D and 3D methods, and carefully selecting similarity coefficients based on the specific goal are all strategies that have been empirically shown to yield significant performance enhancements. As the field evolves, these traditional fingerprints will continue to serve as both a robust baseline for comparison and a critical component in sophisticated, multi-faceted virtual screening pipelines.

Molecular similarity is a cornerstone concept in drug discovery, rooted in the principle that structurally similar molecules often exhibit similar biological activities [33]. While two-dimensional (2D) fingerprint-based similarity methods are widely used for their speed and simplicity, they often struggle to identify structurally diverse compounds that share the same biological function—a process known as scaffold hopping [3]. To overcome this limitation, researchers are increasingly turning to three-dimensional (3D) methods. These approaches consider the spatial conformation and pharmacophoric features of molecules, which are critical for complementary binding to a protein target. This guide provides a comparative analysis of modern 3D shape similarity and pharmacophore alignment methods, detailing their underlying principles, performance, and practical applications to inform selection for virtual screening and lead optimization campaigns.

Methodologies at a Glance

3D molecular similarity methods can be broadly classified into two categories: those that evaluate the overall shape similarity between molecules, and those that align molecules based on their pharmacophore features—abstract representations of key chemical interactions (e.g., hydrogen bond donors, acceptors, hydrophobic regions) [33] [34]. The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the primary methodologies discussed in this guide.

Table 1: Core 3D Molecular Similarity Methodologies

| Method Category | Key Principle | Representative Tools | Primary Strengths | Common Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Shape Similarity | Maximizes overlap of molecular volumes or compares shape descriptors [33]. | ROSHAMBO [35], ROCS [36], USR [33] | Highly effective for scaffold hopping; does not require a protein structure. | Computationally expensive for large libraries; alignment quality is critical. |

| Pharmacophore Alignment | Alens molecules based on matching chemical feature points (e.g., HBD, HBA, hydrophobic) [34]. | Pharao [34], DiffPhore [37], PharmacoMatch [38] | Provides interpretable interaction models; can be derived from ligands or protein structures. | Requires pre-generated conformers; feature perception can be subjective. |

| Negative Image-Based (NIB) | Uses the inverted shape of the protein binding cavity as a docking template or for rescoring [39]. | O-LAP [39], PANTHER [39] | Directly encodes target structure constraints; can improve docking enrichment. | Dependent on quality and size of the protein structure's binding cavity. |