Molecular Engineering Thermodynamics: Fundamentals for Drug Design and Biomedical Innovation

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of molecular engineering thermodynamics, bridging fundamental principles with cutting-edge applications in drug discovery and biomedical research.

Molecular Engineering Thermodynamics: Fundamentals for Drug Design and Biomedical Innovation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive exploration of molecular engineering thermodynamics, bridging fundamental principles with cutting-edge applications in drug discovery and biomedical research. Tailored for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it details the energetic forces driving molecular interactions, from foundational laws and statistical mechanics to practical methodologies like calorimetry and computational modeling. The content further addresses critical challenges such as entropy-enthalpy compensation, offers strategies for thermodynamic optimization in ligand design, and validates approaches through comparative analysis of experimental and computational data. By synthesizing these domains, the article serves as a vital resource for leveraging thermodynamic insights to develop more effective and specific therapeutic agents.

The Energetic Blueprint: Core Principles of Molecular Interactions

Laws of Thermodynamics and Their Molecular Interpretation

The laws of thermodynamics form the foundational framework governing energy, entropy, and the direction of spontaneous processes in physical systems. Within molecular engineering, these principles provide the predictive power necessary to design advanced technologies at the molecular and nano scales, from targeted drug delivery systems to novel energy storage materials [1]. This whitepaper delineates the core thermodynamic laws through a molecular lens, providing researchers and drug development professionals with the theoretical tools to manipulate molecular interactions systematically. The molecular interpretation of these laws bridges macroscopic observables with microscopic behavior, enabling the rational design of molecular systems with tailored properties.

The Zeroth Law and Thermal Equilibrium

Macroscopic Statement and Definition

The Zeroth Law of Thermodynamics establishes the transitive property of thermal equilibrium: if two systems are each in thermal equilibrium with a third system, then they are in thermal equilibrium with each other [2]. This law provides the empirical basis for temperature as a fundamental and measurable property, allowing for the creation of reliable temperature scales.

Molecular Interpretation of Temperature

At the molecular level, temperature is a direct measure of the average kinetic energy associated with the random motion of particles within a system [3]. When two bodies at different temperatures make contact, molecular collisions at the interface facilitate energy transfer. Higher-energy molecules in the hotter body transfer kinetic energy to lower-energy molecules in the colder body through these collisions. Thermal equilibrium is achieved when the average molecular kinetic energy equalizes across both systems, resulting in no net heat flow [3]. This state defines temperature equality from a molecular perspective.

The First Law and Energy Conservation

The Principle of Energy Conservation

The First Law of Thermodynamics is a restatement of energy conservation for thermodynamic systems. It asserts that energy cannot be created or destroyed, only transformed between different forms or transferred between a system and its surroundings [2] [4]. The change in a system's internal energy (ΔU) is mathematically given by: ΔU = Q - W where Q is the heat added to the system, and W is the work done by the system on its surroundings [2]. Alternative conventions exist, but this formulation defines work as energy expended by the system.

Molecular Basis of Internal Energy, Heat, and Work

- Internal Energy (U): At the molecular level, internal energy is the sum of the kinetic and potential energies of all constituent particles [3]. Kinetic energy components include translational, rotational, and vibrational motions, while potential energy arises from intermolecular forces such as van der Waals interactions and hydrogen bonding [3].

- Heat Transfer (Q): Heat represents energy transfer driven by a temperature gradient. Molecularly, this occurs through collisions between particles or the transfer of vibrational, rotational, or electronic energy. During phase changes like vaporization, added heat overcomes intermolecular attractive forces without increasing temperature [3].

- Work (W): Work involves energy transfer through organized, macroscopic motion against an external force. During gas expansion, for example, the collective motion of molecules pushing against a piston represents work done by the system, thereby reducing its internal energy [3].

Table 1: Molecular Components of Internal Energy

| Energy Mode | Molecular Origin | Example |

|---|---|---|

| Translational Kinetic | Motion of the entire molecule through space | Ideal gas molecules |

| Rotational Kinetic | Rotation of the molecule about its center of mass | Diatomic molecule spinning |

| Vibrational Kinetic | Periodic displacement of atoms within a molecule | Stretching of a chemical bond |

| Potential Energy | Intermolecular forces and interactions | Hydrogen bonding in water |

The Second Law and Entropy

The Direction of Spontaneous Processes

The Second Law of Thermodynamics states that for any spontaneous process, the total entropy of the universe always increases [4]. In all its formulations, it emphasizes the irreversibility of natural processes and the fact that heat cannot spontaneously flow from a colder to a hotter body [2].

Molecular Interpretation of Entropy

Entropy (S) is quantitatively related to the number of possible microstates (W) — the different microscopic arrangements of molecular positions and energies — that correspond to a single macroscopic state [3]. A system with a greater number of accessible microstates has higher entropy and is more disordered.

Processes that increase entropy include:

- Volume expansion of a gas: Molecules can occupy a larger volume, vastly increasing the number of possible positional arrangements [5].

- Phase changes from solid to liquid to gas: Molecular order decreases, and freedom of motion increases, leading to a dramatic increase in the number of microstates [5].

- Dissolving a solute: Solute particles gain new accessible volume and configurations within the solvent [5].

Conversely, reactions that decrease the number of gas molecules (e.g., ( 2NO{(g)} + O{2(g)} \rightarrow 2NO_{2(g)} )) reduce entropy because the physical bonding of atoms restricts their freedom of movement, decreasing the number of microstates [5].

Table 2: Molecular Motions and Their Contribution to Entropy

| Molecular Freedom | Description | Impact on Entropy |

|---|---|---|

| Translational | Movement through space in three dimensions | Highest contribution; increases with available volume |

| Rotational | Rotation around molecular axes | Significant contribution; depends on molecular structure |

| Vibrational | Internal vibration of atomic bonds | Lower contribution; more significant at higher temperatures |

Gibbs Free Energy and Spontaneity

The Gibbs Free Energy (G) combines enthalpy and entropy to predict process spontaneity at constant temperature and pressure: G = H - TS A process is spontaneous when the change in Gibbs Free Energy is negative (ΔG < 0). This provides a crucial tool for molecular engineers to design processes and reactions by balancing energy (H) and disorder (S) [3].

The Third Law and the Absolute Zero

The Law of Minimal Entropy

The Third Law of Thermodynamics states that the entropy of a perfect crystalline substance approaches zero as its temperature approaches absolute zero (0 Kelvin) [5] [2] [4]. A "perfect crystal" implies a single, perfectly ordered arrangement of atoms, molecules, or ions in a well-defined lattice with no impurities or defects [4].

Molecular Basis and Implications

In a perfect crystal at 0 K, all molecular motion ceases: translations and rotations stop, and vibrations reach their minimal quantum mechanical ground state [5]. The system is locked into a single, unique microstate (W=1). Since entropy is related to the number of microstates, it reaches a minimum value of zero [4]. This law provides a fundamental reference point, enabling the calculation of absolute entropy values at other temperatures, which are essential for determining ΔG in chemical reactions [4].

Diagram: The number of accessible microstates decreases with temperature, reaching a single microstate for a perfect crystal at absolute zero, corresponding to zero entropy.

Experimental Protocols in Molecular Thermodynamics

Protocol: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for Binding Energetics

Objective: To directly measure the enthalpy change (ΔH), binding affinity (Kd), stoichiometry (n), and entropy change (ΔS) of a molecular interaction (e.g., drug-protein binding).

Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely purify and buffer-exchange the macromolecule (e.g., protein) and ligand (e.g., drug candidate). Degas all solutions to prevent bubble formation.

- Instrument Setup: Load the macromolecule solution into the sample cell and the ligand solution into the syringe. Set the target temperature with high stability (±0.001°C).

- Titration and Data Acquisition: Program a series of sequential injections of the ligand into the macromolecule cell. After each injection, the instrument automatically measures the nanocalories of heat absorbed or released to maintain the isothermal condition.

- Data Analysis: Integrate the raw heat peaks from each injection. Fit the resulting binding isotherm (heat vs. molar ratio) to a suitable binding model to extract ΔH, Kd, and n. Calculate the Gibbs Free Energy using ΔG = -RT ln(Ka) (where Ka = 1/Kd). Finally, derive the entropic contribution from the relationship: ΔG = ΔH - TΔS.

Protocol: Determination of Phase Equilibria for Mixture Design

Objective: To experimentally map the phase diagram of a binary or ternary mixture, critical for designing separation processes (e.g., distillation, extraction) in pharmaceutical synthesis.

Methodology:

- Apparatus Preparation: Utilize a variable-volume equilibrium cell with transparent windows, pressure sensors, and temperature control.

- Loading and Equilibration: Load the cell with a mixture of known overall composition. Set the desired temperature and adjust the cell volume/pressure until a second phase (e.g., bubble or droplet) is visually observed, indicating the phase boundary.

- Sampling and Analysis: At equilibrium, simultaneously sample from each coexisting phase (e.g., liquid and vapor). Analyze the composition of each phase using analytical techniques such as Gas Chromatography (GC) or High-Performance Liquid Chromatography (HPLC).

- Diagram Construction: Repeat the procedure across a range of temperatures and compositions. Plot the data to construct pressure-composition (P-x-y) or temperature-composition (T-x-y) phase diagrams, which define the regions of stability for different phases.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Materials for Molecular Thermodynamics Research

| Reagent/Material | Function and Molecular Relevance |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Buffer Systems | Provides a stable, defined ionic environment (pH) for biomolecular interactions, ensuring consistent protonation states and minimizing non-specific binding in ITC experiments. |

| Calorimetry Reference Cell Solution | Typically pure water or buffer. Serves as a thermal reference to accurately measure the minute heat changes in the sample cell, enabling precise determination of ΔH. |

| Analytical Chromatography Columns | (GC/HPLC) Used for high-resolution separation and quantitative analysis of mixture components in phase equilibrium studies. |

| Certified Standard Gases & Liquids | Substances with known and certified thermodynamic properties (e.g., heat capacity, enthalpy of vaporization). Used for calibration and validation of thermal analysis instruments. |

| Perfect Crystal Model Systems | Materials like high-purity argon or simple organics that form near-perfect crystals. Used in low-temperature calorimetry to experimentally verify the Third Law and measure absolute entropies. |

The laws of thermodynamics, when interpreted through a molecular lens, transition from abstract principles to a practical design framework for molecular engineers. Understanding that temperature reflects average kinetic energy, entropy quantifies molecular disorder, and the laws set ultimate limits on energy conversion, empowers researchers to innovate rationally. This molecular-level understanding is indispensable for tackling complex challenges in drug development, from predicting ligand-receptor binding affinities to designing scalable and efficient synthesis and purification processes. The continued integration of these fundamental principles with computational modeling and advanced experimental protocols will undoubtedly drive the next generation of breakthroughs in molecular engineering and pharmaceutical sciences.

The rational design of molecules, a core objective of molecular engineering, relies on a profound understanding of the forces governing molecular recognition. Whether engineering a therapeutic antibody, a synthetic enzyme, or a biosensor, the interaction between a molecule and its target is quantified by its binding affinity. This affinity is thermodynamically defined by the Gibbs Free Energy of binding (ΔG), a composite parameter whose value determines the spontaneity of the binding event [6]. A fundamental principle of molecular engineering thermodynamics is that ΔG is not a direct measurable force but is instead a derived quantity governed by the interplay of two distinct thermodynamic components: the enthalpy change (ΔH) and the entropy change (ΔS), related by the equation ΔG = ΔH - TΔS [7] [6] [8].

The relationship ΔG = ΔH - TΔS is deceptively simple. Its profound implication is that an identical binding affinity (the same ΔG) can be achieved through a wide spectrum of vastly different molecular mechanisms, each with a unique thermodynamic signature defined by its specific ΔH and -TΔS values [7]. The enthalpy change, ΔH, reflects the net energy from the formation and breaking of non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and van der Waals contacts, between the ligand, the target, and the solvent. The entropy change, -TΔS, encompasses changes in molecular freedom, including the favorable hydrophobic effect (which is entropically driven) and the often-unfavorable loss of conformational, rotational, and translational freedom upon binding [7] [9].

For the molecular engineer, these thermodynamic signatures are not merely academic; they are crucial design parameters. A drug candidate with a binding affinity driven predominantly by entropy (e.g., through the hydrophobic effect) may have different pharmaceutical properties, such as solubility, compared to one driven by enthalpy (e.g., through specific hydrogen bonds) [9]. Recent research has demonstrated that these signatures can even influence functional biological outcomes beyond mere binding. For instance, in the development of HIV-1 cell entry inhibitors, the unwanted triggering of a conformational change in the viral gp120 protein was directly correlated with a specific enthalpically-driven thermodynamic signature, similar to that of the natural receptor CD4 [7]. This guide will deconstruct the interplay of ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS, providing molecular engineers with the theoretical framework and experimental toolkit to harness these principles for advanced molecular design.

Theoretical Foundations: The Thermodynamic Equation of State

The Meaning of ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS

The Gibbs Free Energy change (ΔG) is the ultimate determinant of binding spontaneity under constant temperature and pressure conditions. Its value, which can be measured experimentally via the dissociation constant ((K_D)), dictates the equilibrium between bound and unbound states [8]. The relationship is given by:

ΔG = RT ln((K_D)) [8]

where (R) is the gas constant and (T) is the absolute temperature in Kelvin. The sign and magnitude of ΔG directly correspond to the feasibility and strength of binding, as summarized in Table 1.

Table 1: The Meaning of ΔG Values in Binding Interactions

| ΔG Value | Interpretation | Binding Outcome |

|---|---|---|

| ΔG < 0 | Spontaneous | Favorable, occurs naturally |

| ΔG > 0 | Non-spontaneous | Unfavorable, requires energy input |

| ΔG = 0 | System at equilibrium | Forward and reverse rates are equal |

The two components that constitute ΔG have distinct molecular origins:

- Enthalpy (ΔH): This represents the heat change during binding at constant pressure. A favorable (negative) ΔH typically indicates the formation of strong, specific non-covalent interactions at the binding interface, such as hydrogen bonds, salt bridges, and van der Waals interactions. An unfavorable (positive) ΔH suggests that more energy is required to break existing interactions (e.g., desolvation of polar groups) than is gained from forming new ones [7] [9].

- Entropy (-TΔS): Entropy (ΔS) is a measure of disorder or randomness. The term -TΔS contributes to the free energy. A favorable (negative) -TΔS, which results from a positive ΔS, is often associated with the hydrophobic effect, where the release of ordered water molecules from hydrophobic surfaces into the bulk solvent increases the system's disorder. An unfavorable (positive) -TΔS is common and arises from the severe restriction of a ligand's and protein's conformational and translational/rotational freedoms upon forming a stable complex [7] [9].

The Interplay of ΔH and ΔS in Determining ΔG

Because ΔG is the sum of ΔH and -TΔS, many different combinations can yield the same overall affinity. The generalization of how these components interact to determine spontaneity is summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: General Conditions for Spontaneous Binding (ΔG < 0)

| ΔH | ΔS | -TΔS | Contribution to ΔG | Condition for Spontaneity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Negative (Favorable) | Positive (Favorable) | Negative (Favorable) | Always Negative | Spontaneous at all temperatures |

| Positive (Unfavorable) | Negative (Unfavorable) | Positive (Unfavorable) | Always Positive | Non-spontaneous at all temperatures |

| Negative (Favorable) | Negative (Unfavorable) | Positive (Unfavorable) | Depends on balance | Spontaneous at low temperatures |

| Positive (Unfavorable) | Positive (Favorable) | Negative (Favorable) | Depends on balance | Spontaneous at high temperatures |

A critical phenomenon in molecular recognition is enthalpy-entropy compensation, where a favorable change in enthalpy is partially or wholly offset by an unfavorable change in entropy, and vice versa [9]. This compensation makes it challenging to improve overall binding affinity by optimizing only one parameter. For example, introducing a new hydrogen bond to make ΔH more negative may immobilize flexible groups, making ΔS more negative and thus reducing the net gain in ΔG. A key goal in molecular engineering is to overcome this compensation to achieve simultaneous improvement in both enthalpy and entropy [9].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Direct Measurement of Binding Thermodynamics with Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) is the premier experimental technique for a full thermodynamic characterization of a binding interaction in a single experiment. It directly measures the heat released or absorbed during the binding reaction, providing direct access to ΔH, the binding constant ((KA = 1/KD)), and thus ΔG and ΔS [7] [9].

Detailed Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely prepare solutions of the ligand and the macromolecular target in the same buffer to eliminate heats of dilution. Degas samples to prevent bubble formation in the instrument.

- Instrument Setup: Load the target solution into the sample cell and the ligand solution into the injection syringe. Set the experimental temperature, stirring speed, and the number/timing of injections.

- Titration and Data Acquisition: The instrument performs a series of automated injections of the ligand into the target cell. After each injection, the instrument measures the microcalories of heat required to maintain the sample cell at the same temperature as a reference cell.

- Data Analysis: The plot of heat released per injection versus the molar ratio is integrated to yield a binding isotherm. Nonlinear regression of this isotherm directly provides the enthalpy change (ΔH), the association constant ((K_A)), and the stoichiometry (n) of binding.

- Derivation of Thermodynamic Parameters:

- ΔG is calculated from (KA) using: ΔG = -RT ln((KA)).

- ΔS is derived from the relationship: ΔS = (ΔH - ΔG)/T.

To measure the heat capacity change (ΔC~p~), a key parameter indicative of the burial of surface area upon binding, a series of ITC experiments must be conducted at different temperatures. The slope of a plot of ΔH versus temperature yields ΔC~p~ [7].

Computational Prediction of Binding Affinity

AI and deep learning methods have emerged as powerful tools for predicting drug-target binding affinity (DTA), accelerating virtual screening in drug discovery [10] [11]. These methods typically treat DTA prediction as a regression task.

Detailed Protocol for a Cross-Scale Graph Contrastive Learning Approach (CSCo-DTA):

- Data Collection and Curation: Assemble a dataset of known drug-target pairs with experimentally measured affinity values (e.g., (KD), (Ki), IC~50~). Key resources include the PPB-Affinity dataset for protein-protein interactions, PDBbind, and BindingDB for drug-target pairs [12] [10] [11].

- Feature Representation:

- Drug Molecules: Represent each drug as a molecular graph where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. Use Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System (SMILES) strings or Extended Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFPs) [10] [11].

- Target Proteins: Represent proteins by their amino acid sequences, or for structure-based methods, as contact maps or 3D grids.

- Model Architecture (CSCo-DTA Example):

- Molecule-Scale Feature Extraction: Use Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) to learn features from the drug molecular graph and the protein contact map [10].

- Network-Scale Feature Extraction: Construct a drug-target bipartite network. Use GNNs to learn features for drugs and proteins from the topology of this network [10].

- Cross-Scale Contrastive Learning: A module designed to maximize mutual information between the molecule-scale and network-scale features of the same drug/target, improving representation learning [10].

- Affinity Prediction: The combined features are fed into a multilayer perceptron (MLP) to predict the continuous binding affinity value [10].

- Model Training and Validation: Train the model on a labeled dataset using a loss function like mean squared error. Critically, assess and mitigate dataset bias, such as the model learning to predict affinity based solely on protein similarity rather than true interaction patterns. Services like BASE provide bias-reduced datasets for more robust model development [11].

Data Presentation and Analysis

Case Study: Thermodynamic Signatures in Drug Discovery

The practical impact of thermodynamic profiling is exemplified by the evolution of HIV-1 protease inhibitors. Analysis of first-in-class versus best-in-class drugs reveals a clear thermodynamic trajectory. First-generation inhibitors often rely heavily on a favorable entropy contribution, typically driven by the hydrophobic effect. In contrast, later, more advanced best-in-class drugs achieve their superior potency and drug-resistance profiles through improved, more favorable enthalpy contributions, indicating better optimization of specific polar interactions with the target [9].

Table 3: Thermodynamic Parameters for CD4/gp120 and Inhibitor Binding at 25°C

| Compound / Protein | ΔG (kcal/mol) | ΔH (kcal/mol) | -TΔS (kcal/mol) | K~D~ | Key Structural Consequence |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CD4 (Protein) | -11.0 | -34.5 | +23.5 | 8 nM | Large conformational structuring of gp120, activating coreceptor site [7] |

| NBD-556 (Inhibitor) | -7.4 | -24.5 | +17.1 | 3.7 µM | Mimics CD4 signature, triggers unwanted conformational change and viral infection [7] |

| Optimized NBD-556 Analogs | ~ -7.4 to -8.4 | Smaller magnitude (e.g., -10) | More Favorable (e.g., +2) | ~0.4 - 3.7 µM | Reduced or eliminated unwanted conformational effects and viral activation [7] |

Table 3 illustrates a critical application of thermodynamic deconstruction. The natural ligand CD4 and the initial inhibitor NBD-556 bind with similar, highly enthalpic signatures, which is structurally linked to a large conformational change that activates the virus. By deliberately modifying the inhibitor to shift its thermodynamic signature toward a less enthalpic and more entropically driven profile—while maintaining or improving affinity—researchers successfully engineered out the unwanted biological functional effect [7]. This demonstrates that for certain targets, the thermodynamic signature (ΔH/-TΔS balance) can be a more important design criterion than the overall binding affinity (ΔG) alone.

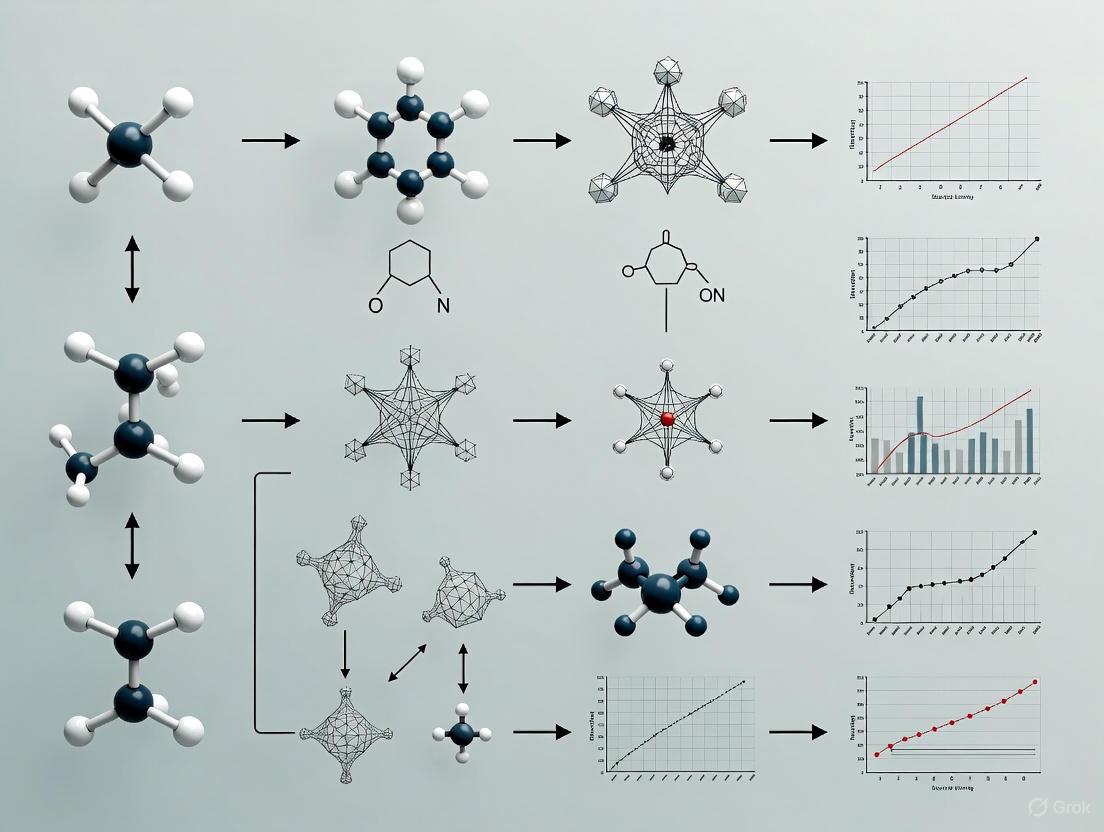

Visualization of Core Concepts and Workflows

Thermodynamic Optimization Plot (TOP)

The Thermodynamic Optimization Plot (TOP) is a conceptual tool to guide the optimization of drug candidates based on their thermodynamic signatures [7]. The plot places ΔH on the y-axis and -TΔS on the x-axis. A lead compound is plotted as a single point on this graph.

Experimental Workflow for Thermodynamic Profiling

The following diagram outlines a comprehensive workflow for determining the thermodynamic profile of a molecular interaction, integrating both experimental and computational approaches.

Successful research in binding thermodynamics and affinity prediction relies on a suite of experimental, computational, and data resources.

Table 4: Research Reagent Solutions for Binding Affinity Studies

| Category / Item | Function / Description | Key Examples / Databases |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental Instrumentation | Directly measures the heat change during binding to obtain full thermodynamic profile. | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) [7] [9] |

| Computational Datasets | Provides curated, experimental data for training and validating AI/ML models for affinity prediction. | PPB-Affinity (Protein-Protein) [12]; PDBbind (general biomolecular) [12] [11]; BindingDB (drug-target) [11] |

| Bias-Reduced Data Services | Provides datasets processed to reduce similarity bias, improving model generalizability. | BASE (Binding Affinity Similarity Explorer) [11] |

| Molecular Representation Tools | Converts molecular structures into numerical features or graphs for machine learning. | RDKit (for ECFP fingerprints) [11]; Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [10] |

| AI Model Architectures | Deep learning frameworks that integrate multiple data types (sequence, structure, network) for accurate affinity prediction. | CSCo-DTA (Cross-Scale Graph Model) [10]; SSM-DTA (Semi-supervised Model) [11] |

The deconstruction of binding affinity into its fundamental thermodynamic components, ΔH and ΔS, provides molecular engineers with a powerful, multi-dimensional framework for design that transcends the one-dimensional metric of ΔG. As demonstrated, the thermodynamic signature of a molecular interaction is not merely a reflection of affinity but is deeply encoded with structural and functional information, governing phenomena from conformational change to drug resistance. The integration of direct experimental measurement via ITC with modern computational approaches like cross-scale AI models represents the cutting edge of molecular engineering thermodynamics. By leveraging the tools, datasets, and conceptual frameworks outlined in this guide—particularly the Thermodynamic Optimization Plot—researchers can now deliberately engineer molecules not just for strong binding, but for the specific, desired thermodynamic character that translates to efficacy and safety in real-world applications.

Statistical mechanics is a foundational mathematical framework that applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities, thereby connecting the microscopic world of atoms and molecules to the macroscopic thermodynamic properties observed in engineering and biological systems [13]. Its primary purpose is to clarify the properties of matter in aggregate—such as temperature, pressure, and heat capacity—in terms of physical laws governing atomic motion [13]. For researchers in molecular engineering and drug development, this connection is paramount; it allows the prediction of bulk material behavior or the binding affinity of a drug candidate from the statistical analysis of molecular-level interactions. This guide elucidates the core principles, quantitative data, and experimental methodologies of statistical mechanics, framing them within the context of molecular engineering thermodynamics fundamentals research.

Theoretical Foundations and Historical Context

The development of statistical mechanics in the 19th century, credited to James Clerk Maxwell, Ludwig Boltzmann, and Josiah Willard Gibbs, provided a bridge between Newtonian or quantum mechanics and classical thermodynamics [13]. The field addresses a central problem: a macroscopic system comprises an astronomically large number of particles (on the order of 10²³), making it impossible to track each one individually [14]. Statistical mechanics solves this by considering macroscopic variables as averages over microscopic ones.

The core of the framework is the concept of a statistical ensemble [13]. Whereas ordinary mechanics considers the behavior of a single state, statistical mechanics introduces a large collection of virtual, independent copies of the system in various states. This ensemble is a probability distribution over all possible microstates of the system. The evolution of this ensemble is governed by the Liouville equation (classical mechanics) or the von Neumann equation (quantum mechanics) [13]. When this ensemble does not evolve over time, the system is in a state of statistical equilibrium, the focus of statistical thermodynamics. The most critical postulate for isolated systems is the equal a priori probability postulate, which states that for a system with a known energy and composition, all accessible microstates are equally probable [13]. From this foundation, the three primary equilibrium ensembles are derived.

The following table summarizes the three key equilibrium ensembles used to describe systems at the macroscopic limit, each corresponding to different experimental conditions.

Table 1: Key Equilibrium Ensembles in Statistical Mechanics

| Ensemble Name | System Description | Fixed Parameters | Fluctuating Quantity | Probability Distribution | Connection to Thermodynamics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Microcanonical | Isolated system [13] | Energy (E), Volume (V), Particle Number (N) [13] | None | Equal probability for all microstates consistent with E, V, N [13] | Direct calculation of entropy: ( S = k_B \ln \Omega ) |

| Canonical | System in thermal equilibrium with a heat bath [13] | Temperature (T), Volume (V), Particle Number (N) | Energy (E) | Boltzmann Distribution: ( P(Ei) \propto e^{-Ei / k_B T} ) [14] | Helmholtz free energy: ( F = -k_B T \ln Z ) |

| Grand Canonical | System in thermal and chemical equilibrium with a reservoir [13] | Temperature (T), Volume (V), Chemical Potential (μ) | Energy (E), Particle Number (N) | ( P(Ei, Nj) \propto e^{-(Ei - \mu Nj) / k_B T} ) | Landau free energy: ( \Omega = -k_B T \ln \Xi ) |

These ensembles provide the mathematical machinery to derive macroscopic thermodynamic properties from the microscopic description. For example, the pressure exerted by a gas in a balloon is not felt as individual molecular collisions but as the average momentum transfer per unit area from a vast number of molecules [14]. Similarly, temperature is related to the average kinetic energy of the constituent particles [14].

Experimental Protocol: Validating Statistical Mechanics in Granular Materials

While traditional statistical mechanics deals with thermal systems, its principles have been extended to non-equilibrium and athermal systems. A key experimental validation involves applying a statistical mechanics framework to granular materials (e.g., sand, sugar), which are ubiquitous in pharmaceutical manufacturing and powder processing.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Granular Packing Experiments

| Item Name | Function/Description | Experimental Role |

|---|---|---|

| 3D-Printed Plastic Beads | Millimeter-sized model grains with tunable surface properties [15] | Serves as the model granular material for the experiment. |

| Roughness-Modified Beads | Beads with engineered surface textures to control inter-particle friction [15] | Allows systematic study of friction's effect on packing statistics and ensemble validity. |

| X-ray Tomography System | Non-invasive 3D imaging apparatus [15] | Precisely monitors and reconstructs the configuration (positions, contacts) of the beads within the container. |

| Periodic Tapping Device | Electromagnetic shaker or mechanical tapper [15] | Provides controlled, periodic excitation to the system, mimicking "thermal" noise and driving it towards stationary states. |

| Edwards' Canonical Volume Ensemble | Theoretical framework where volume plays the role of energy [15] | Provides the statistical model against which experimental volume distribution data is validated. |

Detailed Experimental Methodology

The following workflow details the procedure used to test the Edwards volume ensemble for granular packings [15]:

- System Preparation: 3D-printed plastic beads of several millimeters in diameter are placed in a container. Beads with different surface roughnesses are used in separate experimental runs to investigate the role of friction.

- Protocol-Driven Excitation: The system is excited via periodic tapping of the container. The intensity of the taps is carefully controlled. This excitation randomizes the particle configurations, helping the system reach a stationary state that is independent of its initial preparation history.

- Configuration Imaging: After the system reaches a stationary state under a given tapping intensity, the precise 3D configuration of the beads is captured using x-ray tomography.

- Subsystem Volume Calculation: The central innovation involves defining a "subsystem" as a spherical region of fixed diameter centered on a particle. The volume of this local subsystem is calculated precisely from the tomographic data. Many such subsystems from a single container are treated as independent realizations of the same system for statistical analysis.

- Probability Distribution Analysis: The probability distribution of the subsystem volumes is constructed from the data. Researchers then test whether this distribution follows the functional form predicted by Edwards' canonical volume ensemble.

- Calculation of State Variables: The compactivity (a temperature-like variable for granular materials) and the granular entropy are calculated from the volume distribution data.

This methodology successfully demonstrated that the volume fluctuations in these excited granular systems obey the principles of a statistical ensemble, thereby validating a statistical mechanics approach for this athermal material [15].

Experimental workflow for granular statistical mechanics

Advanced Concepts and Molecular Engineering Applications

Quantum Statistics and Entropy

For molecular systems at the quantum level, the evaluation of the statistical weight of a macrostate must account for the indistinguishability of particles. This leads to two forms of quantum statistics [14]:

- Fermi-Dirac Statistics: Governs particles (like electrons) that obey the Pauli exclusion principle, where no more than one particle can occupy a given quantum state. This is crucial for understanding the behavior of electrons in materials and the structure of atoms, which underlies molecular interactions in drug design.

- Bose-Einstein Statistics: Governs particles (like photons) that can condense into the same quantum state. This explains phenomena such as superconductivity and the behavior of liquid helium.

The entropy, a central concept in thermodynamics, is quantitatively defined in statistical mechanics as being proportional to the logarithm of the number of microstates corresponding to a given macrostate [14]. The evolution of a system toward equilibrium is a move toward more probable macrostates, culminating in the state of maximum entropy [14].

Applications in Modeling and Drug Development

The principles of statistical mechanics are directly applicable to challenges in molecular engineering and drug development:

- Boltzmann's Law: This law states that the probability of a molecular arrangement varies exponentially with the negative of its potential energy divided by ( k_B T ) [14]. This explains and allows for the modeling of evaporation and the exponential variation of atmospheric density with altitude. In molecular contexts, it governs the distribution of ions across a membrane or the binding equilibrium between a protein and a drug candidate.

- Analysis of Fluctuations: Statistical mechanics provides the tools to understand and quantify random fluctuations, such as Brownian motion, which results from the impact of individual molecules on a small macroscopic particle [14]. This is fundamental to dynamic light scattering and other techniques used to characterize biomolecules in solution.

The following diagram illustrates the fundamental logical relationship connecting microscopic behavior to macroscopic observables, which is the core of statistical mechanics.

Logic of statistical mechanics

Intermolecular Forces and Their Role in Biological System Energetics

Intermolecular forces (IMFs) represent the fundamental interactions governing the behavior, stability, and function of biological systems at the molecular level. These forces, which include London dispersion forces, dipole-dipole interactions, and hydrogen bonding, dictate a vast array of physiological and pathological processes by modulating the energetics of molecular recognition, self-assembly, and nano-bio interfaces. Within the framework of molecular engineering thermodynamics, a quantitative understanding of these forces enables the rational design of advanced biomedical technologies. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical examination of IMFs, detailing their theoretical foundations, experimental characterization, and critical role in applications ranging from drug delivery to cancer therapeutics. It is intended to equip researchers and drug development professionals with the methodologies and insights required to harness these forces in the development of next-generation molecular solutions.

Theoretical Foundations of Intermolecular Forces

Intermolecular forces are attractive or repulsive forces between molecules that are distinct from the intramolecular forces that bind atoms together within a molecule. The energy associated with these forces is central to the thermodynamics of molecular interactions in condensed phases, influencing physical properties such as boiling point, solubility, and viscosity [16]. The primary types of IMFs, in order of typical increasing strength, are:

London Dispersion Forces: These are the weakest of all IMFs and are present in all atoms and molecules, regardless of polarity. They arise from temporary, instantaneous dipoles created by the asymmetrical distribution of electrons around the nucleus. This temporary dipole can induce a dipole in a neighboring atom or molecule, resulting in a weak electrostatic attraction. The strength of dispersion forces increases with the polarizability of a molecule—the ease with which its electron cloud can be distorted. Larger atoms and molecules with more electrons are generally more polarizable, leading to stronger dispersion forces [16]. For example, the trend in boiling points of the halogens (F₂ < Cl₂ < Br₂ < I₂) directly correlates with increasing molar mass and atomic radius, which enhances the strength of dispersion forces [16].

Dipole-Dipole Interactions: These occur between molecules that possess permanent molecular dipoles, meaning they have a permanent separation of positive and negative charge. Polar molecules align themselves so that the positive end of one molecule is attracted to the negative end of an adjacent molecule. These interactions are stronger than London dispersion forces and are a key factor in determining the properties of polar substances [16].

Hydrogen Bonding: This is a special category of dipole-dipole interaction that occurs when a hydrogen atom is covalently bonded to a highly electronegative atom (typically nitrogen (N), oxygen (O), or fluorine (F)). The hydrogen atom acquires a significant partial positive charge, allowing it to form a strong electrostatic attraction with a lone pair of electrons on another electronegative atom. Hydrogen bonding is exceptionally important in biological systems, governing the structure of proteins and nucleic acids, and the properties of water [17] [16].

The phase in which a substance exists—solid, liquid, or gas—depends on the balance between the kinetic energies (KE) of its molecules and the strength of the intermolecular attractions. Lower temperatures or higher pressures favor the condensed phases (liquid and solid) where IMFs dominate over KE [16].

Intermolecular Forces at the Nano-Bio Interface

The interaction between engineered nanomaterials and biological systems is governed by the complex interplay of intermolecular forces at the nano-bio interface. The physicochemical properties of nanoparticles (NPs)—such as size, shape, surface characteristics, roughness, and surface coating—directly determine the nature and strength of these interactions, which in turn dictate biocompatibility, bioadverse outcomes, and therapeutic efficacy [18].

When nanoparticles are introduced into a biological environment, they immediately interact with cell membranes and biomolecules. These interactions are mediated by the same fundamental IMFs described above. For instance:

- Hydrogen bonding and dipole-dipole interactions can govern the adsorption of proteins and lipids onto the NP surface, forming a "corona" that defines the biological identity of the particle.

- London dispersion forces become increasingly significant with the size and polarizability of both the NP and the biological molecules it encounters.

- Electrostatic interactions (which can be considered a form of ion-dipole force) between charged functional groups on the NP surface and charged components of the cell membrane are also critical.

Studying these relationships is paramount for designing efficient nanostructures for biomedical applications like drug delivery and cancer therapy. As concluded in a 2025 review, understanding the influences at the interface "allows us to understand the influences these have on the final fate of these nanostructures, making them more efficient and effective in the fight against cancer" [18]. Recent advances, including the study of exosomal corona formation and calcium-functionalized nanomaterials, are reshaping the understanding of cancer nanotherapy through the lens of intermolecular forces [18].

Quantitative Data and Trends

The following tables summarize key quantitative relationships that demonstrate the influence of intermolecular forces on physical properties, providing a basis for predictive molecular design.

Table 1: Effect of Molecular Size on Physical Properties via Dispersion Forces This table illustrates how increasing molar mass and atomic radius strengthen London dispersion forces, leading to higher melting and boiling points in a homologous series (data for halogens) [16].

| Halogen | Molar Mass (g/mol) | Atomic Radius (pm) | Melting Point (K) | Boiling Point (K) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| F₂ | 38 | 72 | 53 | 85 |

| Cl₂ | 71 | 99 | 172 | 238 |

| Br₂ | 160 | 114 | 266 | 332 |

| I₂ | 254 | 133 | 387 | 457 |

Table 2: Boiling Points and Primary Intermolecular Forces of Common Solvents This data, relevant to experimental work, shows how molecular polarity and the ability to form hydrogen bonds significantly elevate boiling points [17].

| Liquid | Molar Mass (g/mol) | Primary Intermolecular Force | Boiling Point (°C) * |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hexane | 86.18 | London Dispersion | ~69 |

| Ethyl Acetate | 88.11 | Dipole-Dipole | ~77 |

| 1-Butanol | 74.12 | Hydrogen Bonding | ~118 |

| Ethanol | 46.07 | Hydrogen Bonding | ~78 |

| Water | 18.02 | Hydrogen Bonding | 100 |

*Representative values; exact figures may vary.

Table 3: Impact of Molecular Branching on Boiling Point Molecular shape affects the surface area available for intermolecular contact, thereby influencing the strength of dispersion forces. This table compares isomers of C₅H₁₂ [16].

| Isomer | Structure | Boiling Point (°C) |

|---|---|---|

| n-Pentane | Linear | 36 |

| Isopentane | Moderately Branched | 27 |

| Neopentane | Highly Branched | 9.5 |

Experimental Protocols for Characterizing Intermolecular Forces

Solubility Testing Protocol

Objective: To determine the miscibility of various organic liquids with water and relate the results to the strengths and types of intermolecular forces present.

Methodology:

- Materials:

- Chemicals: Deionized water, methanol, ethanol, isopropyl alcohol, 1-butanol, ethyl acetate, butyl acetate, hexane.

- Equipment: Seven small test tubes, test tube rack, 1 mL pipettes, non-halogenated organic waste container [17].

Procedure:

- Label seven test tubes from 1 to 7.

- To each test tube, add 1 mL of deionized water.

- Add 1 mL of the assigned liquid to each corresponding test tube:

- Test tube 1: Methanol

- Test tube 2: Ethanol

- Test tube 3: Isopropyl alcohol

- Test tube 4: 1-Butanol

- Test tube 5: Ethyl acetate

- Test tube 6: Butyl acetate

- Test tube 7: Hexane

- Gently shake each test tube for a consistent duration and observe the mixture immediately after shaking.

- Record whether the liquid is soluble (forms one homogeneous phase) or insoluble (forms two distinct phases) in water.

- Dispose of all mixtures in the appropriate non-halogenated organic waste container [17].

Data Interpretation:

- Liquids that are readily soluble in water typically can form strong intermolecular forces with water, such as hydrogen bonding (e.g., methanol, ethanol).

- Liquids that are insoluble lack the ability to form strong enough interactions to overcome the hydrogen-bonding network of water (e.g., hexane).

Evaporation Rate and Temperature Change Protocol

Objective: To measure the cooling effect of various liquids during evaporation and correlate the temperature change with the strength of the intermolecular forces present.

Methodology:

- Materials:

- Chemicals: The same liquids as in the solubility test.

- Equipment: Well plate, Celsius thermometer or temperature probe, 600 mL beaker for waste [17].

Procedure:

- Half-fill separate wells of a well plate with each of the liquids to be tested.

- For the first liquid (e.g., deionized water), immerse the thermometer bulb or probe and wait for the reading to stabilize. Record this as the initial temperature.

- Remove the thermometer from the liquid, hold it in the air, and wait for the temperature to stabilize again. Record this as the final temperature.

- Calculate ΔT = Tinitial - Tfinal.

- Clean and dry the thermometer before repeating the procedure for each subsequent liquid.

- Upon completion, dispose of all liquids in the non-halogenated organic waste container [17].

Data Interpretation:

- A larger temperature drop (ΔT) indicates greater cooling upon evaporation.

- The cooling effect is directly related to the energy required to overcome the liquid's IMFs and transition to the vapor phase. Liquids with stronger overall IMFs (like those with hydrogen bonding) will require more energy to evaporate, leading to a more pronounced cooling effect.

Visualization of Molecular Interactions and Energetics

Hierarchy of Intermolecular Forces

Nano-Bio Interface Interaction Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Investigating Intermolecular Forces in Biological Contexts

| Reagent/Material | Function in Experimental Research |

|---|---|

| Alkanes (e.g., Hexane) | Serves as a model non-polar solvent dominated by London dispersion forces; used as a baseline for solubility and evaporation studies [17]. |

| Polar Aprotic Solvents (e.g., Ethyl Acetate) | Used to study dipole-dipole interactions in the absence of hydrogen bonding; important for understanding solvent effects on molecular recognition [17]. |

| Alcohols (e.g., Methanol, Ethanol, 1-Butanol) | A homologous series used to investigate the strength and effects of hydrogen bonding, and the interplay between alkyl chain length (dispersion forces) and polar head groups [17]. |

| Functionalized Nanoparticles | Engineered NPs with controlled surface chemistry (e.g., -COOH, -NH₂, PEG) are essential for probing specific IMFs (H-bonding, electrostatic) at the nano-bio interface [18]. |

| Cell Membrane Models (e.g., Liposomes) | Simplified biological membrane systems used in vitro to study the fundamental interactions of NPs with lipid bilayers, governed by a combination of IMFs [18]. |

| Spectroscopic Tools (FTIR, NMR) | Used to characterize molecular-level interactions, such as hydrogen bonding strength and conformational changes, in both small molecules and complex nano-bio systems. |

The Molecular Basis of Entropy and Enthalpy in Drug-Target Recognition

The rational design of high-affinity drugs hinges on a quantitative understanding of the molecular forces governing target recognition. The binding interaction between a drug candidate and its biological target is quantified by the Gibbs free energy change (ΔG), which is related to enthalpic (ΔH) and entropic (TΔS) components through the fundamental equation ΔG = ΔH - TΔS [19]. A more negative ΔG signifies stronger binding. The enthalpic component (ΔH) primarily reflects the formation of favorable non-covalent interactions, such as hydrogen bonds and van der Waals forces, between the drug and the target. The entropic component (-TΔS) encompasses changes in the disorder of the system, including the loss of conformational freedom upon binding and the release of ordered water molecules from the binding interfaces. A pervasive and challenging phenomenon in this realm is entropy-enthalpy compensation, where a favorable change in one thermodynamic parameter (e.g., a more negative ΔH) is offset by an unfavorable change in the other (e.g., a more negative TΔS), resulting in little to no net improvement in binding affinity (ΔΔG ≈ 0) [19]. This compensation can severely frustrate rational drug design efforts, as engineered enthalpic gains are negated by entropic penalties.

Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation: Evidence and Implications

Experimental Evidence in Protein-Ligand Binding

Calorimetric studies, particularly using Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC), have generated significant evidence for entropy-enthalpy compensation in various ligand-binding systems. A meta-analysis of approximately 100 protein-ligand complexes revealed a linear relationship between ΔH and TΔS with a slope near unity, suggesting a severe form of compensation [19].

Specific case studies further illustrate this phenomenon:

- In a congeneric series of para-substituted benzamidinium inhibitors of trypsin, the free energy of binding remained almost constant despite large, opposing variations in ΔH and TΔS [19].

- A study on HIV-1 protease inhibitors demonstrated that introducing a hydrogen bond acceptor yielded a favorable enthalpic gain of 3.9 kcal/mol, which was entirely counterbalanced by an entropic penalty, yielding no net affinity increase [19].

- Research on thrombin ligands and trypsin inhibitors with expanded nonpolar rings also reported apparent compensation, attributed to factors like solvent ordering and non-additive effects [19].

Ramifications for Ligand Engineering

The occurrence of severe entropy-enthalpy compensation poses a significant challenge in drug discovery [19]. It implies that:

- Hydrogen Bond Engineering: Strategies to improve affinity by introducing hydrogen bond donors or acceptors may fail if the enthalpic benefit is canceled by a conformational entropic penalty.

- Rigidification Strategies: Efforts to reduce unfavorable entropy by adding internal constraints or removing rotatable bonds to limit flexibility could induce equivalent enthalpic penalties.

- Lead Optimization Frustration: This compensation can lead to non-additive effects, where individual ligand modifications do not translate to expected improvements in overall binding affinity, complicating the lead optimization process.

Quantitative Data on Thermodynamic Compensation

The following table summarizes key experimental observations of entropy-enthalpy compensation from the literature, highlighting the interplay between these parameters across different systems.

Table 1: Experimental Observations of Entropy-Enthalpy Compensation in Protein-Ligand Binding

| System Studied | Modification | ΔΔH (kcal/mol) | TΔΔS (kcal/mol) | ΔΔG (kcal/mol) | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HIV-1 Protease Inhibitors [19] | Introduction of a hydrogen bond acceptor | ≈ -3.9 | ≈ -3.9 | ≈ 0.0 | Severe compensation; enthalpic gain offset by entropic loss. |

| Benzamidinium Inhibitors of Trypsin [19] | Para-substituent variations | Large variation | Large, opposing variation | Minimal variation | Weak compensation within a congeneric series. |

| Thrombin Ligands [19] | Chemical modifications to ligand scaffold | Competing changes | Competing changes | Non-additive | Apparent compensation responsible for non-additivity. |

| Trypsin Ligands [19] | Expansion of a nonpolar ring (benzo group addition) | Favorable change | Unfavorable change | Minimal net change | Compensation attributed to solvent ordering effects. |

Methodologies for Thermodynamic Profiling

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) is a primary experimental technique for directly measuring the thermodynamics of biomolecular interactions [20]. A single ITC experiment provides estimates of the association constant (Ka), and the enthalpy change (ΔH), from which ΔG and TΔS are derived [19]. ITC works by measuring the heat released or absorbed during the binding reaction, providing a complete thermodynamic profile—affinity, enthalpy, and entropy—without the need for labeling or immobilization.

Table 2: Key Methodologies for Evaluating Drug-Target Binding Thermodynamics

| Method | Measured Parameters | Key Advantage | Consideration |

|---|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) [19] [20] | Directly measures ΔH, Ka (from which ΔG and TΔS are derived). | Label-free; provides a complete thermodynamic profile (ΔG, ΔH, TΔS) from a single experiment. | Requires relatively high concentrations of protein and ligand. |

| Van't Hoff Analysis [19] | Determines ΔH, ΔS from the temperature dependence of Ka. | Can be applied to data from various techniques (e.g., fluorescence). | Requires multiple accurate measurements across a temperature range; potential for large errors if linked to heat capacity changes. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

The following table details key reagents and materials essential for conducting thermodynamic evaluations of protein-drug interactions.

Table 3: Research Reagent Solutions for Thermodynamic Binding Studies

| Reagent / Material | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Protein Target | The isolated and purified biological macromolecule (e.g., enzyme, receptor). Requires high purity and stability for reliable calorimetric or spectroscopic data. |

| Characterized Ligand Library | A series of small molecule inhibitors or drug candidates, often congeneric. Structural characterization is vital for correlating thermodynamic data with chemical features. |

| ITC Buffer System | A carefully chosen aqueous buffer that maintains protein stability and activity without generating high background heats from mixing (e.g., during titrations). |

| Calorimeter (ITC Instrument) | The microcalorimetry instrument used to directly measure heat changes upon binding, enabling the determination of ΔH, Ka, and stoichiometry. |

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Thermodynamic Analysis Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the primary experimental and computational workflow for determining and analyzing the thermodynamics of drug-target recognition.

Molecular Determinants of ΔH and TΔS

This diagram deconstructs the key molecular-level contributions to the overall enthalpic and entropic changes observed during drug-target binding.

Understanding the molecular basis of entropy and enthalpy is paramount for advancing rational drug design. The frequent observation of entropy-enthalpy compensation underscores the complexity of molecular recognition, where optimizing one thermodynamic parameter in isolation is often insufficient. Future research must continue to develop more precise experimental and computational methods to disentangle these compensatory effects. A focus on directly assessing changes in binding free energy (ΔG), while leveraging detailed thermodynamic profiles to understand the underlying mechanism, will be crucial for overcoming the challenges posed by compensation and for engineering next-generation therapeutic agents with high affinity and specificity.

From Theory to Therapy: Measuring and Applying Energetic Data

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) is a powerful analytical technique that provides a direct, label-free method for measuring the thermodynamic parameters of molecular interactions in solution. As a cornerstone of molecular engineering thermodynamics, ITC uniquely quantifies the heat changes that occur when two molecules bind, enabling researchers to obtain a complete thermodynamic profile of biomolecular interactions in a single experiment [21] [22]. This capability makes ITC an indispensable tool for fundamental research in biophysics and drug development, offering insights into the forces driving molecular recognition processes that underlie cellular function and therapeutic intervention.

Unlike indirect binding measurement techniques that require labeling or immobilization, ITC measures the inherent heat signature of binding events, providing unperturbed access to the energetic components of molecular interactions [21] [23]. The technique has evolved from specialized applications to a mainstream method capable of characterizing interactions between diverse biomolecules including proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, carbohydrates, and small molecule ligands [22] [24]. For molecular engineering research, ITC provides the critical link between structural information and functional energetics, enabling rational design based on thermodynamic principles.

Theoretical Foundations and Thermodynamic Principles

The fundamental basis of ITC lies in its ability to directly measure the enthalpy change (ΔH) occurring when a ligand binds to its macromolecular target. This direct measurement, combined with the binding constant (K~a~) obtained from the titration isotherm, provides access to the complete thermodynamic profile of the interaction through standard thermodynamic relationships [22]:

The Gibbs free energy change is calculated from the binding constant: ΔG = -RTlnK~a~

The entropy change is derived from the relationship: ΔG = ΔH - TΔS

where R is the gas constant, T is the absolute temperature, and K~a~ is the association constant [22].

This thermodynamic dissection reveals the fundamental forces driving the binding event. Enthalpy changes (ΔH) reflect the formation and breaking of non-covalent bonds including hydrogen bonds, van der Waals interactions, and electrostatic effects. Entropy changes (ΔS) primarily reflect alterations in solvation and conformational freedom [25]. The balance between these components has profound implications for molecular engineering, particularly in drug discovery where enthalpy-driven binders often demonstrate superior selectivity compared to entropy-driven compounds [25].

The c-Value and Experimental Design

A critical parameter in ITC experimental design is the c-value, which determines the shape and interpretability of the binding isotherm [21]:

c = n·[M]~cell~/K~D~

where n is the stoichiometry, [M]~cell~ is the concentration of the macromolecule in the cell, and K~D~ is the dissociation constant.

The c-value dictates the optimal concentration range for ITC experiments. Values between 10-100 yield sigmoidal binding isotherms that allow accurate determination of both K~D~ and n [21]. At c < 10, stoichiometry cannot be accurately determined, while at c > 1000, the dissociation constant cannot be precisely measured, though stoichiometry remains accessible [21]. This relationship guides researchers in selecting appropriate concentrations for characterizing interactions of varying affinities.

Instrumentation and Measurement Methodology

Instrument Design and Operation

The ITC instrument consists of two identical cells constructed of thermally conducting, chemically inert materials such as Hastelloy alloy or gold, surrounded by an adiabatic jacket to minimize heat exchange with the environment [22]. The sample cell contains the macromolecule solution, while the reference cell typically contains buffer or water [22]. A precise syringe, positioned with its tip near the bottom of the sample cell, delivers sequential injections of the ligand solution [26] [22].

The core measurement principle involves maintaining thermal equilibrium between the sample and reference cells throughout the titration. When binding occurs after an injection, heat is either released (exothermic reaction) or absorbed (endothermic reaction), creating a temperature differential between the cells [22]. Highly sensitive thermopile or thermocouple circuits detect this difference, triggering a feedback mechanism that activates heaters to restore thermal equilibrium [22]. The power required to maintain equal temperatures is recorded as a function of time, with each injection producing a peak corresponding to the heat flow [22].

Figure 1: ITC Measurement Principle and Workflow. The diagram illustrates the sequential phases of an ITC experiment from ligand injection to parameter determination.

Quantitative Data Output

The raw data from an ITC experiment appears as a series of heat flow peaks corresponding to each injection. Integration of these peaks with respect to time yields the total heat exchanged per injection [27] [22]. When plotted against the molar ratio of ligand to macromolecule, these integrated heat values produce a binding isotherm that can be fitted to appropriate binding models to extract thermodynamic parameters [27].

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic Parameters Measured by ITC

| Parameter | Symbol | Units | Interpretation | Typical Range |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dissociation Constant | K~D~ | M | Binding affinity; lower values indicate tighter binding | 10⁻² - 10⁻¹² M [23] |

| Enthalpy Change | ΔH | kcal/mol | Heat released or absorbed during binding | -20 to +20 kcal/mol |

| Entropy Change | ΔS | cal/mol·K | Changes in disorder and solvation | Variable |

| Gibbs Free Energy | ΔG | kcal/mol | Overall energy driving binding; must be negative for spontaneous binding | Typically -6 to -15 kcal/mol |

| Stoichiometry | n | - | Number of binding sites per macromolecule | 0.5 - 2 for simple systems |

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Sample Preparation Requirements

Proper sample preparation is critical for successful ITC experiments, with buffer matching representing the most crucial factor. The two binding partners must be in identical buffers to minimize heats of dilution that can obscure the heats of binding [21]. Even minor differences in pH, salt concentration, or additive concentrations can cause significant heat effects that interfere with accurate measurement [21] [27].

For systems involving DMSO, extreme care must be taken as DMSO has high heats of dilution and should be matched "extremely well" between the cell and syringe [21]. Reducing agents can cause erratic baseline drift and artifacts; TCEP is recommended over β-mercaptoethanol and DTT, with concentrations kept at ≤1 mM, especially when the binding enthalpy is small [21]. The use of degassed buffers reduces the introduction of air bubbles that can compromise data quality [22].

Concentration Guidelines and c-Value Optimization

Appropriate concentration selection is essential for obtaining interpretable ITC data. The following table summarizes typical starting concentrations for a 1:1 binding interaction:

Table 2: ITC Sample Requirements and Concentration Guidelines

| Parameter | Sample Cell (Macromolecule) | Syringe (Ligand) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Volume | ≥300 µL (200 µL cell + filling) | 100-120 µL (40 µL syringe + filling) | Exact volumes vary by instrument [21] [26] |

| Concentration | 5-50 µM (at least 10× K~D~) | 50-500 µM (≥10× cell concentration) | Must yield c-value between 10-100 [21] |

| Purity | >90% recommended [28] | High purity essential | Aggregates interfere with measurements [21] |

| Buffer | Identical for both partners | Identical for both partners | Mismatch causes large dilution heats [21] |

| DMSO | Match exactly between solutions | Match exactly between solutions | High heat of dilution [21] [27] |

The c-value equation (c = n·[M]~cell~/K~D~) guides concentration selection [21]. For characterization of unknown affinities, preliminary experiments at different concentrations may be necessary to achieve optimal c-values between 10-100.

Standard Titration Protocol

A typical ITC experiment follows a standardized protocol [26]:

Dialysis and Buffer Matching: Dialyze both interaction partners against identical buffer using appropriate molecular weight cut-off membranes. For small peptides, Pur-A-Lyzer dialysis tubes with 1 kDa MWCO are recommended [26].

Instrument Preparation: Power on the ITC instrument at least one day before use for optimal stability [22]. Determine instrument noise level by titrating water into water; a noise level <1.5 microCal/sec is deemed acceptable [26].

Sample Preparation: Concentrate or dilute samples to target concentrations in matched dialysis buffer. Centrifuge proteins/peptides for 3-5 minutes at 12,300 × g immediately before the experiment to remove aggregates [26].

Loading: Carefully load the sample cell with macromolecule solution (~350 µL for 200 µL cell) using a Hamilton syringe, avoiding bubbles [26]. Fill the titration syringe with ligand solution (minimum 80 µL for 40 µL syringe) [26].

Parameter Settings: Configure experimental parameters [26]:

- Reference power: 5 µcal/sec

- Temperature: Set according to system requirements (typically 20-25°C)

- Stirring speed: 750 rpm

- Initial delay: 60 seconds

- Injection sequence: 22 injections of 2.0 µL each, 4-second duration, 180-second spacing

Data Collection: Initiate the automated titration and monitor baseline stability throughout the experiment.

Control Experiment: Perform a control titration of ligand into buffer alone to measure heats of dilution.

Data Analysis Workflow

Analysis of ITC data typically follows this sequence [27]:

Peak Integration: Integrate each injection peak from baseline to obtain total heat per injection.

Dilution Correction: Subtract control heats of dilution from sample data.

Curve Fitting: Fit the corrected binding isotherm to an appropriate binding model (typically one-site binding for simple interactions).

Parameter Extraction: Obtain K~A~ (association constant), ΔH (enthalpy change), and n (stoichiometry) from the fit.

Derived Parameters: Calculate ΔG = -RTlnK~A~ and ΔS = (ΔH - ΔG)/T.

Figure 2: Thermodynamic Parameter Relationships in ITC Data Analysis. The diagram illustrates how directly measured parameters are used to calculate the complete thermodynamic profile.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Successful ITC experiments require careful selection of reagents and materials to ensure data quality and reproducibility. The following toolkit outlines essential components:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Materials for ITC

| Category | Specific Items | Function and Importance | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buffers | Phosphate, HEPES | Low heat of ionization; recommended for ITC | Avoid TRIS which has high ionization heat [27] |

| Reducing Agents | TCEP | Maintain protein reduction with minimal artifacts | Preferred over βMe and DTT; use ≤1 mM [21] |

| Dialysis | 12 kDa MWCO tubes (proteins), 1 kDa MWCO Pur-A-Lyzer (peptides) | Achieve exact buffer matching | Critical for minimizing dilution heats [26] |

| Filtration | Millex-GP Syringe Filters (0.22 µm) | Remove aggregates and particulates | Centrifuge or filter samples before use [21] [26] |

| Consumables | 0.2 mL tubes for syringe filling [21] | Sample handling and loading | Ensure compatibility with instrument |

| Cleaning | Water, methanol [21] | Instrument maintenance | Prevent cross-contamination between experiments |

Applications in Molecular Engineering and Drug Discovery

ITC provides critical insights for molecular engineering thermodynamics, particularly in structure-based design and lead optimization. The technique's ability to dissect binding energy into enthalpic and entropic components enables researchers to understand the physical basis of molecular recognition [25].

In drug discovery, ITC serves as a key technology for hit validation and lead optimization. Initial screening compounds often exhibit predominantly entropic binding energetics dominated by hydrophobic interactions [25]. Through thermodynamic-guided optimization, researchers can introduce enthalpic contributions by incorporating targeted hydrogen bonds or electrostatic interactions, potentially achieving higher affinity and selectivity [25]. Enthalpically optimized compounds can achieve much higher binding affinities than their entropically optimized counterparts, as entropic optimization based on hydrophobicity faces practical limits due to solubility constraints [25].

ITC also provides critical quality control by measuring binding stoichiometry, enabling evaluation of the proportion of the sample that is functionally active [29]. This application is particularly valuable for characterizing protein fragments, catalytically inactive mutant enzymes, and engineered binding domains [29].

Advanced Applications and Specialized Methodologies

Beyond standard binding characterization, ITC supports several advanced applications:

Competitive Titration for High-Affinity Interactions

For interactions with very high affinity (K~D~ < 10⁻⁹ M) that exceed the direct measurement range of ITC, competitive binding experiments extend the technique's capabilities [23]. In this approach, a high-affinity ligand is displaced from its target by an even higher-affinity competitor, allowing determination of affinities in the picomolar range (10⁻⁹ to 10⁻¹² M) [23].

Temperature Dependence and Heat Capacity Measurements

Performing ITC experiments at multiple temperatures provides access to the heat capacity change (ΔC~p~) of binding, calculated from the temperature dependence of ΔH [30]. Heat capacity changes provide insights into burial of solvent-accessible surface area during binding and can signal conformational changes coupled to the binding event [30].

Protonation Linkage Analysis

When binding is coupled to protonation/deprotonation events, ITC can characterize the associated proton movement by performing experiments in buffers with different ionization enthalpies [29] [30]. This approach provides information on the ionization of groups involved in binding and their contribution to the overall binding energetics.

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry provides a direct, label-free method for comprehensively characterizing the thermodynamics of molecular interactions. Its unique ability to simultaneously determine binding affinity, enthalpy, entropy, and stoichiometry in a single experiment makes it an invaluable tool for fundamental research in molecular engineering thermodynamics. As drug discovery increasingly focuses on designing compounds with optimal selectivity and physicochemical properties, ITC's capacity to guide enthalpy-driven optimization represents a critical advantage. When implemented with careful attention to sample preparation, buffer matching, and concentration optimization, ITC delivers unparalleled insights into the energetic forces governing molecular recognition, establishing it as an essential technique in the biophysical toolkit.

Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations are cornerstone computational techniques in molecular engineering, enabling the prediction of material properties and system behaviors from the atomistic to the mesoscale. Molecular engineering thermodynamics relies on these methods to bridge the gap between classical, statistical, and molecular descriptions of matter, providing insights crucial for fields ranging from drug development to energy materials [31] [32]. While both are powerful tools for sampling molecular configurations, their underlying principles and applications differ significantly. MD simulation is a deterministic technique that follows the natural time evolution of a system by solving Newton's equations of motion, thereby providing dynamic information and transport properties [33]. In contrast, MC simulation is a stochastic method that generates a sequence of random states to build up a probabilistic sample of the system's configuration space, making it exceptionally powerful for determining equilibrium properties and free energies [34]. This technical guide examines the core principles, methodologies, and applications of both approaches within the context of molecular engineering thermodynamics research.

Fundamental Principles

Molecular Dynamics Foundations

Molecular Dynamics is a deterministic methodology that numerically solves Newton's equations of motion for a system of interacting atoms:

[ \vec{F}i(t) = mi \frac{d^2\vec{r}_i(t)}{dt^2} ]

where (\vec{F}i(t)) is the force on atom (i) at time (t), (mi) is its mass, and (\vec{r}_i(t)) is its position vector [33]. The forces are derived from a potential energy function (force field) that describes the interatomic interactions. By integrating these equations numerically, MD generates a trajectory of the system's atomic positions and velocities over time, providing access to both structural and dynamic properties.

The fundamental strength of MD lies in its ability to model time-dependent phenomena and transport properties, such as diffusion coefficients, viscosity, and conformational changes in biomolecules. Recent advances include the development of "ultrafast molecular dynamics approaches" that significantly improve computational efficiency for studying complex systems like ion exchange polymers, with one study reporting a ~600% increase in equilibration efficiency compared to conventional methods [35].

Monte Carlo Foundations

Monte Carlo methods are stochastic approaches that use random sampling to solve mathematical and physical problems. Unlike MD, MC does not simulate the actual dynamics of a system but instead generates a Markov chain of states that collectively sample from a specified statistical mechanical ensemble [34]. The core principle involves accepting or rejecting randomly generated trial moves according to an energy-based criterion, most commonly the Metropolis criterion:

[ P_{acc}(o \rightarrow n) = \min\left(1, e^{-\beta \Delta U}\right) ]

where (\Delta U = Un - Uo) is the energy difference between the new and old states, and (\beta = 1/k_B T) [33] [34].

MC simulations are particularly valuable for calculating equilibrium properties, free energies, and sampling complex energy landscapes. Their non-dynamic nature allows for the use of specialized sampling moves that would be physically unrealistic but mathematically valid for enhancing configurational sampling, making them highly efficient for certain classes of problems [34].

Comparative Analysis: MD vs. MC

Table 1: Fundamental comparison between Molecular Dynamics and Monte Carlo simulation approaches.

| Feature | Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Monte Carlo (MC) |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Principle | Deterministic; solves Newton's equations of motion | Stochastic; based on random sampling and acceptance criteria |

| Time Dependence | Provides real dynamical information and time evolution | No real time dependence; generates ensemble averages |

| Natural Ensemble | Microcanonical (NVE) | Canonical (NVT) |