Molecular Engineering: Principles, Applications, and AI-Driven Advances in Drug Development

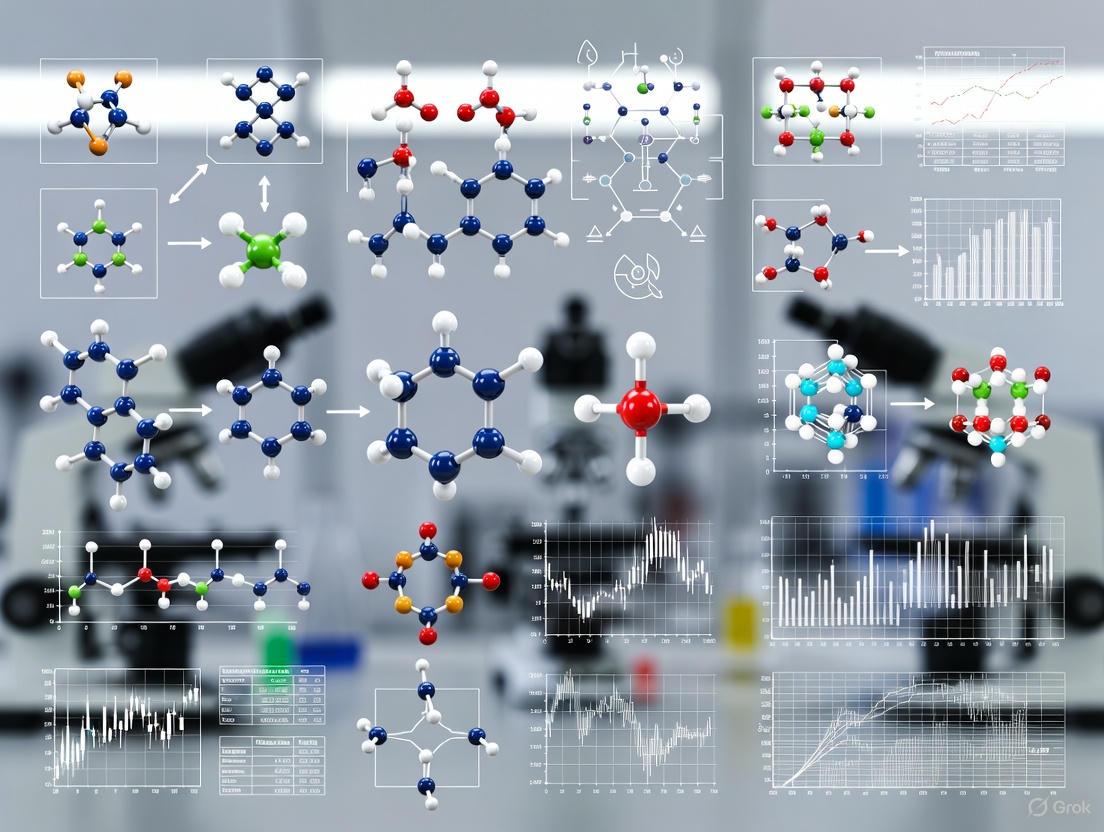

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular engineering, an interdisciplinary field focused on the rational design and synthesis of molecules to achieve specific functions.

Molecular Engineering: Principles, Applications, and AI-Driven Advances in Drug Development

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of molecular engineering, an interdisciplinary field focused on the rational design and synthesis of molecules to achieve specific functions. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores foundational 'bottom-up' principles, key methodological approaches in biotechnology and electronics, and the pivotal role of AI in troubleshooting complex optimization challenges. It further examines validation strategies and comparative analyses of computational tools that are revolutionizing the pace of discovery, with a particular emphasis on transformative applications in biomedicine.

The Foundations of Molecular Engineering: A Bottom-Up Approach to Designing Matter

Molecular engineering represents a fundamental shift in the approach to designing and constructing functional materials and devices. It is defined as the design and synthesis of molecules with specific properties and functions in mind, essentially constituting a form of "bottom-up" engineering that uses molecules and atoms as building blocks [1]. This discipline moves beyond merely observing molecules as subjects of scientific inquiry to actively engineering with molecules, selecting those with the right chemical, physical, and structural properties to serve as the foundation for new technologies or the optimization of existing ones [2].

The core paradigm involves selecting molecules with the desired properties and organizing them into specific nanoscale architectures to achieve a target product or process [2]. This approach often draws inspiration from nature, where complex molecular architectures like DNA and proteins demonstrate sophisticated functionality that molecular engineering seeks to understand, mimic, and even improve upon [2] [1]. Unlike traditional engineering disciplines, where scaling down macroscopic equations is sufficient, molecular engineering operates at a scale where these conventional equations break down, necessitating new models that account for the unique properties substances exhibit at the molecular and nanoscale level [2].

Core Principles and Methodologies

The Molecular Engineering Process

The practice of molecular engineering typically follows a systematic cycle of design, synthesis, and characterization. The process begins with molecular design, where a molecule is conceptualized based on its intended application, such as a drug for a specific disease or a catalyst for a particular reaction [1]. Design strategies can involve modifying existing molecules with new chemical groups to alter properties like hydrophobicity and electronic environment, or de novo design, which creates entirely new chemical structures from scratch without a template, a method common in protein engineering [1].

A pivotal methodology in this domain is Computer-Aided Molecular Design (CAMD). CAMD is defined as a technique that, given a set of building blocks and a set of target properties, determines the molecule or molecular structure that matches these requirements [3]. It integrates structure-based property prediction models—such as group contribution methods, quantitative structure-property relationships (QSPR), and molecular descriptors—with optimization algorithms to design optimal molecular structures possessing desired physical and/or thermodynamic properties [3]. This framework tackles the reverse problem of property estimation: instead of determining properties from a known structure, it identifies structures that deliver a specified set of properties [3].

Computational molecular modeling is extensively used for visualizing molecular structures, predicting properties, and understanding interactions. It employs mathematical models and algorithms, increasingly including machine learning, to accelerate discovery in areas like drug design (e.g., predicting ligand-target interactions) and materials science (e.g., designing advanced polymers and nanomaterials) [1].

Following design, molecular synthesis is critical. The choice of synthetic method—whether solution-phase synthesis, solid-phase synthesis, click chemistry, or metal-catalyzed coupling reactions—provides control over stereochemistry and molecular weight, which is essential for ensuring the final engineered molecule possesses the desired properties and functions [1].

Finally, characterization is indispensable for verifying that engineered molecules meet their design specifications. A vast array of techniques is employed, including spectroscopic methods (NMR, Mass, IR Spectroscopy), microscopy (TEM, SEM, AFM), crystallography (X-ray), thermal analysis (DSC, TGA), and chromatographic techniques (HPLC, UPLC) [1]. This comprehensive analysis confirms the success of the engineering process and provides insights that can inspire future designs.

Key Quantitative Benchmarks and Data

The field relies on standardized benchmarks to evaluate the efficacy of new design and prediction methodologies. A significant contribution is MoleculeNet, a large-scale benchmark for molecular machine learning [4]. MoleculeNet curates multiple public datasets, establishes evaluation metrics, and provides high-quality implementations of featurization and learning algorithms. Its benchmarks demonstrate that learnable representations are powerful tools but also highlight challenges, such as struggles with complex tasks under data scarcity and the critical importance of physics-aware featurizations for quantum mechanical and biophysical datasets [4].

The following table summarizes a selection of key datasets used for benchmarking in molecular machine learning, illustrating the diversity of tasks and data types:

Table 1: Selected MoleculeNet Benchmark Datasets for Molecular Property Prediction

| Category | Dataset Name | Data Type | Task Type | Number of Compounds | Recommended Metric |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics | QM9 | SMILES, 3D coordinates | Regression (12 tasks) | 133,885 | MAE |

| Physical Chemistry | ESOL | SMILES | Regression (1 task) | 1,128 | RMSE |

| Physical Chemistry | Lipophilicity | SMILES | Regression (1 task) | 4,200 | RMSE |

| Biophysics | - | - | - | - | - |

Recent research introduces even more comprehensive multi-modal benchmarks like ChEBI-20-MM, which encompasses 32,998 molecules characterized by 1D textual descriptors (SMILES, InChI, SELFIES), 2D graphs, and external information like captions and images [5]. Such resources facilitate the evaluation of model performance across a wide range of tasks, from molecule generation and captioning to property prediction and retrieval. Analysis of modal transition probabilities within such benchmarks helps identify the most suitable data modalities and model architectures for specific task types, guiding more efficient research and development [5].

Experimental and Computational Protocols

Detailed CAMD Methodology

The Computer-Aided Molecular Design (CAMD) workflow is a structured process for in silico molecular discovery. The following diagram illustrates the key stages of a generalized CAMD protocol, particularly for a solvent design application:

CAMD Workflow for Molecular Design

The methodology can be broken down into the following detailed steps:

Problem Definition: Precisely define the set of target properties (e.g., solubility parameters, toxicity, boiling point) and their required values or ranges. Structural constraints (e.g., allowable functional groups, molecular complexity) are also established at this stage [3].

Model Selection: Choose appropriate structure-property relationship models. These are often Group Contribution (GC) methods, where molecular properties are estimated as the sum of contributions from the constituent functional groups. Other models include Quantitative Structure-Property Relationships (QSPR) and models based on molecular descriptors [3].

Optimization Formulation: Formulate the design problem as a Mixed-Integer Non-Linear Programming (MINLP) problem. The objective function can be single-objective (e.g., minimizing cost) or multi-objective (e.g., balancing performance and environmental impact). Algorithms like the weighted sum, sandwich algorithm, or Non-dominated Sorting Genetic Algorithm-II (NSGA-II) are employed to navigate the complex search space [3].

Candidate Generation: The optimization algorithm systematically combines the predefined building blocks (functional groups) to generate molecular structures that satisfy the property and structural constraints [3].

Validation: The top-ranking candidate molecules are then synthesized and characterized experimentally to validate the model predictions and confirm their performance in the real-world application [3] [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Molecular engineering relies on a suite of computational and experimental tools. The following table details key resources, particularly for a computational design campaign.

Table 2: Key Reagents and Materials for Computational Molecular Design

| Item / Resource | Function / Description | Application Example |

|---|---|---|

| SMILES/String | A line notation for representing molecular structures using ASCII strings. | Standardized representation of molecules for database storage, search, and as input for machine learning models [4] [5]. |

| DeepChem Library | An open-source toolkit for the application of deep learning to molecular science problems. | Provides high-quality implementations of featurization methods and learning algorithms for molecular machine learning tasks [4]. |

| Group Contribution Parameters | Parameters for property prediction models based on the contributions of functional groups. | Used in CAMD to predict thermodynamic and physical properties of candidate molecules without experimental data [3]. |

| MoleculeNet Datasets | Curated public datasets for benchmarking molecular machine learning algorithms. | Serves as a standard benchmark to compare the efficacy of new machine learning methods for property prediction [4]. |

| RDKit | Open-source cheminformatics software. | Used to generate 2D molecular graphs from SMILES strings, calculate molecular descriptors, and handle chemical data [5]. |

Applications and Current Research Trends

Key Application Domains

Molecular engineering has enabled breakthroughs across a diverse spectrum of fields:

Electronics and Nanomaterials: The drive for miniaturization has made molecular engineering essential. It enables the development of conductive polymers, semiconducting molecules, quantum dots, graphene materials, carbon nanotubes, and self-assembled monolayers, which form the core of advanced molecular electronics [1].

Medicine and Healthcare: This is one of the most impactful domains. Applications include drug discovery (designing therapeutic molecules), drug delivery (using engineered nanomaterials as targeted carriers), in vivo imaging, cancer therapy, neuroengineering, and the creation of diagnostic assays [1].

Biotechnology: The field is deeply intertwined with biotechnology, particularly through genetic engineering. Molecular engineering principles have led to more resilient crops, potential cures for genetic disorders, recombinant proteins like insulin, industrial enzymes, and therapeutic antibodies [1].

Environmental Science: Molecular engineering contributes to sustainability through the development of biofuels (engineering microorganisms and enzymes), pollution control (designing molecules to break down toxins), sustainable chemical processes, and environmentally friendly agrochemicals [1].

Smart Materials: Engineers design molecules that respond to specific stimuli (e.g., pH, temperature, light) as building blocks for smart materials. These materials can adapt to their environment, with applications ranging from color-changing pH indicators in bandages to self-healing polymers [1].

Emerging Trends and Future Outlook

Current research is being shaped by several powerful trends, with the integration of artificial intelligence standing out. Machine learning (ML) and large language models (LLMs) are introducing a fresh paradigm for tackling molecular problems from a natural language processing perspective [5]. LLMs enhance the understanding and generation of molecules, often surpassing existing methods in their ability to decode and synthesize complex molecular patterns [5]. Research is now focused on quantifying the match between model and data modalities and identifying the knowledge-learning preferences of these models, using multi-modal benchmarks like ChEBI-20-MM for evaluation [5].

Another significant trend is the refined understanding and application of molecular similarity. Similarity measures serve as the backbone of many machine learning procedures and are crucial for drug design, chemical space exploration, and the comparison of large molecular libraries [6]. Furthermore, the development of multi-objective optimization (MOO) in CAMD is receiving increasing attention, as it allows for the simultaneous consideration of conflicting objectives, such as balancing economic criteria with environmental impact, which cannot easily be combined into a single metric [3]. As these computational tools mature, they are poised to dramatically accelerate the discovery and design of novel molecules, transforming technologies and improving human health.

Molecular engineering represents a foundational shift in materials science, centering on the precise design and synthesis of novel molecules to achieve desirable physical properties and functionalities [7]. At the core of this discipline lies the 'bottom-up' paradigm, a methodology that constructs complex multidimensional structures from fundamental molecular or nanoscale units, mirroring nature's own assembly processes [8]. This approach leverages weak intermolecular interactions—such as van der Waals forces, hydrogen bonding, and hydrophobic effects—to direct the self-organization of materials with defined architectures and properties. Unlike top-down methods that carve out structures from bulk materials, bottom-up assembly builds complexity from simple components, offering unprecedented control over material organization at the nanoscale and microscale. This technical guide explores the fundamental principles, key methodologies, and cutting-edge applications of bottom-up assembly, framing them within the broader context of molecular engineering research and its transformative impact across fields including medicine, biotechnology, and materials science.

The philosophical underpinning of bottom-up assembly is powerfully illustrated in single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM), where diffraction-unlimited super-resolution images are constructed through the gradual accumulation of individual molecular positions over thousands of frames [9]. Each molecule acts as a quantum of information, and when accumulated stochastically, reveals the underlying nanoscale structure—a process analogous to how bottom-up manufacturing builds complex materials from molecular components [9]. This principle of emergent complexity from simple, directed interactions forms the theoretical foundation for the methodologies and applications detailed in this guide.

Fundamental Methodologies and Mechanisms

DNA-Mediated Programmable Assembly

DNA-mediated assembly has emerged as a particularly powerful strategy within the bottom-up paradigm due to the inherent molecular recognition and sequence programmability of DNA molecules [8]. This approach utilizes synthetic DNA strands as addressable linkers that direct the spatial organization of nanoscale building blocks into predetermined architectures. The specificity of Watson-Crick base pairing allows for the design of complex hierarchical structures through complementary interactions, enabling the construction of one-dimensional, two-dimensional, and three-dimensional assemblies with nanometer precision. The versatility of DNA-mediated assembly stems from the ability to functionalize various nanomaterial surfaces with DNA oligonucleotides, which then serve as programmable "bonds" between building blocks. This methodology has been successfully applied to organize metallic nanoparticles, semiconductor quantum dots, and proteins into functional materials with tailored optical, electronic, and catalytic properties.

Table: Key Characteristics of DNA-Mediated Assembly

| Feature | Description | Advantage |

|---|---|---|

| Programmability | Sequence-specific hybridization directs assembly | Enables precise control over geometry and topology |

| Addressability | Unique sequences target specific building blocks | Allows hierarchical organization of multiple components |

| Reversibility | Temperature-dependent hybridization/dehybridization | Facilitates error correction and self-healing |

| Versatility | Compatible with diverse nanomaterials (metals, semiconductors, polymers) | Enables multifunctional material design |

Molecular Engineering of Self-Assembling Nanoparticles

Recent advances in molecular engineering have produced innovative self-assembling polymer nanoparticles that transition from molecular dissolved states to organized structures in response to mild environmental triggers. Researchers at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering have developed a system where polymer-based nanoparticles self-assemble in water upon a slight temperature increase from refrigeration to room temperature [10]. This system eliminates the need for harsh chemical solvents, specialized equipment, or complex processing—addressing major scalability challenges in nanoparticle production for therapeutic delivery.

The molecular design process involved synthesizing and fine-tuning more than a dozen different polymer structures to achieve the desired thermoresponsive behavior [10]. The resulting polymers remain dissolved in cold aqueous solutions but undergo controlled self-assembly into uniformly sized nanoparticles (20-100 nm) when warmed to physiological temperatures. This transition is driven by delicate balance of hydrophobic and hydrophilic interactions within the polymer architecture, which can be precisely engineered at the molecular level to control particle size, morphology, and surface charge. The simplicity of this platform—requiring only temperature modulation for assembly—makes it particularly valuable for applications requiring gentle handling of fragile biological cargoes.

Single-Molecule Approaches as Bottom-Up Quanta

The conceptual framework of bottom-up assembly finds a powerful analogy in single-molecule localization microscopy (SMLM), where the "quanta" are individual fluorescent molecules [9]. In SMLM, the intrinsic sparsity of activated molecules in each measurement frame enables precise localization of individual emitters with nanometer precision, bypassing the diffraction limit of light. As different random subsets of molecules are activated and localized over thousands of frames, a super-resolution image gradually emerges through accumulation of these molecular quanta [9]. This approach exemplifies the core bottom-up philosophy: complex information (a high-resolution image) is reconstructed from the coordinated assembly of minimal information units (single-molecule positions).

The data structure generated by SMLM further reflects bottom-up principles. Rather than producing conventional pixel-based images, SMLM generates molecular coordinate lists—point clouds of continuous spatial coordinates and additional molecular attributes that can be flexibly processed, transformed, and analyzed without information loss [9]. This format enables versatile image operations including drift correction, multi-view registration, and correlation with other microscopy data, demonstrating how bottom-up data structures facilitate more robust and adaptable analytical capabilities compared to traditional top-down formats.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol: Temperature-Triggered Polymer Nanoparticle Assembly

This protocol describes the methodology for creating self-assembling polymer nanoparticles for therapeutic delivery, based on the system developed at UChicago PME [10].

Materials and Reagents:

- Thermoreversible block copolymer (e.g., PLGA-PEG-PLGA triblock copolymer)

- Ultrapure water (4°C)

- Biological cargo (protein, siRNA, or mRNA)

- Cryoprotectant (e.g., trehalose) for lyophilization

- Phosphate buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4

Equipment:

- Temperature-controlled water bath or thermal cycler

- Lyophilizer

- Dynamic light scattering (DLS) instrument for size characterization

- Transmission electron microscope (TEM)

- Zeta potential analyzer

Procedure:

Polymer Solution Preparation: Dissolve the thermoresponsive polymer in cold ultrapure water (4°C) at a concentration of 1-10 mg/mL. Maintain the solution at 4°C throughout preparation to prevent premature assembly.

Cargo Loading: Add the therapeutic cargo (protein or nucleic acid) to the polymer solution at the desired concentration. Gently mix by inversion to avoid foam formation. For protein delivery, typical loading concentrations range from 0.1-1 mg/mL; for siRNA, 10-100 μM.

Thermal Assembly: Transfer the polymer-cargo solution to a water bath or thermal cycler pre-equilibrated to 25°C. Incubate for 15-30 minutes to allow complete nanoparticle assembly. The assembly process is indicated by the solution turning slightly opalescent.

Characterization: Analyze the assembled nanoparticles using DLS to determine size distribution and polydispersity index. Measure zeta potential to assess surface charge. Verify morphology and monodispersity by TEM with negative staining.

Lyophilization (Optional): For long-term storage, add cryoprotectant (5% w/v trehalose) to the nanoparticle suspension and freeze at -80°C for 2 hours. Lyophilize for 24-48 hours until completely dry. The lyophilized powder can be stored at -20°C for several months.

Reconstitution: Reconstitute lyophilized nanoparticles in cold water (4°C) and warm to room temperature immediately before use. The nanoparticles should reassemble with comparable size distribution and cargo encapsulation efficiency.

Validation Experiments:

- Determine encapsulation efficiency using HPLC (for proteins) or fluorescence spectroscopy (for labeled nucleic acids).

- Perform in vitro release studies by dialysis against PBS at 37°C with regular sampling.

- Assess biological activity through cell-based assays or in vivo models relevant to the intended application.

Protocol: DNA-Mediated Assembly of Nanomaterials

This protocol outlines the general approach for using DNA hybridization to direct the organization of nanoscale building blocks into higher-order structures [8].

Materials and Reagents:

- Nanoscale building blocks (gold nanoparticles, quantum dots, proteins)

- DNA-functionalized ligands (thiol-modified DNA for gold, silane-modified for oxides)

- Buffer solutions (PBS, Tris-EDTA, saline buffer)

- Magnesium chloride (MgCl₂, for promoting hybridization)

Functionalization Procedure:

Surface Modification: Incubate nanomaterials with DNA-modified ligands at appropriate stoichiometry. For gold nanoparticles, use thiol-modified DNA (1-100 μM) in low-salt buffer to avoid aggregation.

Purification: Remove excess unbound DNA by repeated centrifugation and washing (for nanoparticles) or dialysis (for larger structures).

Hybridization-Driven Assembly: Mix DNA-functionalized building blocks in stoichiometric ratios in appropriate buffer containing 5-15 mM MgCl₂.

Thermal Annealing: Heat the mixture to 50-60°C (above melting temperature) and cool slowly to room temperature over 4-8 hours to facilitate specific hybridization.

Validation: Confirm assembly using ultraviolet-visible spectroscopy (plasmon shift for metals), gel electrophoresis, and electron microscopy.

Advanced Applications in Synthetic Biology and Medicine

Bottom-Up Construction of Synthetic Cells

The bottom-up paradigm finds one of its most ambitious applications in the construction of synthetic cells (SynCells) from molecular components [11]. This approach aims to assemble minimal cellular systems that mimic fundamental functions of living cells, including metabolism, growth, division, and information processing. Unlike top-down synthetic biology that modifies existing cells, bottom-up SynCell construction starts from non-living molecular building blocks—membranes, genetic material, proteins, and metabolites—to create functional entities that provide insights into fundamental biology and offer applications in medicine, biotechnology, and bioengineering [11].

Key modules being developed for functional SynCells include:

- Compartmentalization Systems: Lipid vesicles, emulsion droplets, polymersomes, and proteinosomes that define cellular boundaries and enable concentration of biomolecules [11].

- Information Processing: Cell-free transcription-translation (TX-TL) systems reconstructed from purified components or based on cellular extracts that enable gene expression [11].

- Metabolic Networks: Reconstituted pathways for energy production (ATP synthesis) and building block synthesis to maintain cellular functions out of thermodynamic equilibrium [11].

- Growth and Division Mechanisms: Systems for membrane synthesis, ribosome biogenesis, and contractile ring formation to enable self-replication [11].

The integration of these modules presents significant challenges, as compatibility between subsystems must be engineered while maintaining functionality. Recent workshops and conferences, such as the inaugural SynCell Global Summit, have brought together researchers worldwide to establish collaborative frameworks for addressing these integration challenges [11].

Table: Functional Modules for Synthetic Cell Construction

| Module | Key Components | Current Status | Major Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| Compartment | Phospholipids, polymers, membranes | Well-established | Compatibility with internal modules |

| Information Processing | DNA, RNA polymerases, ribosomes | Partially functional | Limited efficiency and duration |

| Energy Metabolism | ATP synthase, respiratory chains | Early demonstration | Low energy yield and regeneration |

| Growth & Division | Lipid synthesis, FtsZ proteins | Preliminary | Lack of coordinated control |

| Spatial Organization | DNA origami, protein scaffolds | Early development | Dynamic reorganization |

Therapeutic Delivery Systems

The temperature-triggered polymer nanoparticle platform exemplifies how bottom-up molecular engineering enables advanced therapeutic delivery [10]. This system has demonstrated versatility in encapsulating and delivering diverse biological cargoes:

- Vaccine Development: Nanoparticles carrying protein antigens elicited long-lasting antibody responses in mouse models, demonstrating potential for vaccine applications [10].

- Immunotherapy: For allergic asthma, nanoparticles delivered immune-suppressive proteins to prevent inappropriate immune activation [10].

- Cancer Therapy: Direct tumor injection of nanoparticles carrying siRNA cancer therapeutics resulted in significant tumor growth suppression in murine models [10].

The platform's ability to protect fragile biological cargoes, coupled with its simple production method requiring only temperature shift for assembly, positions it as a promising technology for global health applications where complex manufacturing infrastructure is limited [10]. The freeze-drying capability further enhances stability, enabling storage and transportation without refrigeration.

Quantum Material Engineering

Bottom-up approaches are revolutionizing quantum material synthesis through techniques like molecular beam epitaxy, which builds quantum-grade materials atom by atom [12]. Researchers at the University of Chicago Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering have pioneered a bottom-up method for creating rare-earth ion-doped thin crystals with unique atomic structures ideal for quantum memory and interconnect applications [12]. These materials, such as yttrium oxide crystals doped with erbium ions, are produced at the wafer-scale for potential mass production, demonstrating the scalability of bottom-up manufacturing.

The precisely controlled atomic structure of these materials enables exceptionally long preservation of quantum states—a critical requirement for quantum computing and networking [12]. Recent breakthroughs include the demonstration of a long-coherence spin-photon interface at telecom wavelength, paving the way for quantum memory devices that could form the backbone of a future quantum internet [12]. This application highlights how bottom-up control at the atomic level enables macroscopic quantum technologies with potential for global impact.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table: Key Research Reagents for Bottom-Up Assembly

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Thermoresponsive Polymers | Form nanoparticles upon temperature increase | Drug delivery vehicles, protein encapsulation |

| DNA Oligonucleotides | Programmable linkers for directed assembly | Organized nanostructures, positional control |

| Phospholipids | Form vesicle membranes and compartments | Synthetic cell chassis, drug delivery |

| Cell-Free TX-TL Systems | Enable gene expression without living cells | Synthetic cell information processing |

| Rare-Earth Ions | Quantum states for information storage | Quantum memory devices, spin qubits |

| Functionalized Nanoparticles | Building blocks with specific surface chemistry | Multifunctional materials, sensors |

| Molecular Buffers | Maintain pH and ionic conditions | Biomolecular assembly, stability |

| Crosslinkers | Stabilize assembled structures | Enhanced material durability |

Future Perspectives and Challenges

The continued advancement of bottom-up molecular engineering faces several significant challenges that represent opportunities for future research. For synthetic cell construction, a major hurdle is module integration—achieving compatibility between diverse synthetic subsystems to create a functioning whole [11]. The parameter space for combining essential building blocks is enormous, and theoretical frameworks are needed to predict the behavior and robustness of reconstituted systems when multiple modules are combined [11]. Similar integration challenges exist in nanomaterial assembly, where controlling hierarchical organization across multiple length scales remains difficult.

Technical challenges include improving the efficiency and controllability of bottom-up processes. In synthetic cells, current cell-free gene expression systems have limited protein synthesis capacity compared to living cells [11]. In nanoparticle drug delivery, precise targeting and release kinetics need refinement [10]. For quantum materials, maintaining quantum coherence in larger-scale systems presents difficulties [12].

Ethical considerations must also guide development, particularly for synthetic life forms. Researchers have emphasized the need to safeguard SynCell technologies against accidental and intentional misuse while enabling broad and responsible adoption [11]. Establishing clear ethical frameworks and safety protocols will be essential as these technologies mature.

Despite these challenges, the bottom-up paradigm continues to expand into new domains. Emerging directions include the development of autonomous molecular factories that synthesize complex products, adaptive materials that respond dynamically to their environment, and hybrid living-nonliving systems that combine the robustness of synthetic materials with the complexity of biological functions. As molecular engineering capabilities grow more sophisticated, the bottom-up approach will likely yield increasingly transformative technologies across medicine, computing, and materials science.

The progression of bottom-up assembly reflects a broader shift in scientific methodology—from observation to creation, from analysis to synthesis. As researchers increasingly focus on constructing complex systems from molecular components, they not only create useful technologies but also develop deeper insights into the fundamental organizational principles governing matter across scales. This synergistic relationship between understanding and creation positions bottom-up molecular engineering as a foundational discipline for 21st-century scientific and technological advancement.

Molecular engineering represents a fundamental shift in applied science, focusing on the design and construction of complex functional systems at the molecular scale. This field has evolved from theoretical concepts to practical applications that are revolutionizing medicine and biotechnology. The trajectory from Richard Feynman's visionary 1959 lecture "There's Plenty of Room at the Bottom" to contemporary CRISPR-based therapeutics and synthetic molecular machines demonstrates the remarkable progress in our ability to understand, manipulate, and engineer biological systems with atomic-level precision. This whitepaper examines key technological milestones, current experimental methodologies, and emerging applications that define the state of molecular engineering research, providing researchers and drug development professionals with a comprehensive technical framework for navigating this rapidly advancing field.

The convergence of biological discovery, computational power, and nanoscale fabrication has created an unprecedented opportunity to address fundamental challenges in human health through molecular engineering. By treating biological components as engineerable systems rather than merely observable phenomena, researchers can now design therapeutic solutions with precision that was unimaginable just decades ago. This paradigm shift enables the creation of molecular machines that perform specific mechanical functions, gene-editing systems that rewrite disease-causing mutations, and synthetic biological circuits that reprogram cellular behavior—all representing the practical realization of Feynman's challenge to manipulate matter at the smallest scales.

The CRISPR Revolution: From Bacterial Defense to Precision Medicine

Clinical Translation and Therapeutic Validation

The transition of CRISPR-Cas9 from a bacterial immune mechanism to a human therapeutic platform represents one of the most significant advances in molecular engineering. The 2023 approval of Casgevy, the first CRISPR-based medicine for sickle cell disease and transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia, established the clinical viability of genome editing [13]. This ex vivo approach involves extracting patient hematopoietic stem cells, editing them to produce fetal hemoglobin, and reinfusing them to alleviate disease symptoms. The success of Casgevy has paved a regulatory pathway for subsequent CRISPR therapies and demonstrated that precise genetic modifications can produce durable therapeutic effects in humans.

Recent clinical advances have expanded beyond ex vivo applications to in vivo gene editing. In 2025, researchers achieved a landmark milestone with the first personalized in vivo CRISPR treatment for an infant with CPS1 deficiency, a rare genetic liver disorder [13]. The therapy was developed and delivered in just six months using lipid nanoparticles (LNPs) as a delivery vehicle, with the patient safely receiving multiple doses that progressively improved symptoms. This case established several critical precedents: the feasibility of rapid development of patient-specific therapies, the safety of LNP-mediated in vivo delivery, and the potential for redosing to enhance efficacy—an approach previously considered untenable with viral vectors due to immune concerns [13].

Next-Generation Editing Systems

While CRISPR-Cas9 remains the most widely recognized editing platform, molecular engineering has produced numerous enhanced systems with improved properties:

Compact Editors: Newly discovered Cas12f-based cytosine base editors are sufficiently small to fit within therapeutic viral vectors while maintaining editing efficiency. Through protein engineering, researchers have developed strand-selectable miniature base editors like TSminiCBE, which has demonstrated successful in vivo base editing in mice [14].

Enhanced Cas12f Variants: Dramatically improved versions of compact gene-editing enzymes called Cas12f1Super and TnpBSuper show up to 11-fold better DNA editing efficiency in human cells while remaining small enough for viral delivery [14].

Epigenetic Editors: A single LNP-administered dose of mRNA-encoded epigenetic editors has achieved long-term silencing of Pcsk9 in mice, reducing PCSK9 by approximately 83% and LDL cholesterol by approximately 51% for six months [14]. This approach enables durable, liver-specific gene repression with minimal off-target effects via transient mRNA delivery.

Transposase Systems: Research into Tn7-like transpososomes reveals molecular machines that can cut and paste entire genes into specific genomic locations without creating double-strand breaks [15]. This system uses an RNA-guided mechanism similar to CRISPR but facilitates precise DNA insertion rather than disruptive cutting, potentially offering a more efficient approach to gene integration [15].

Table 1: Comparison of Genome Editing Platforms

| Editing System | Mechanism of Action | Key Advantages | Current Limitations | Therapeutic Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 | Creates double-strand breaks in DNA | Well-characterized, highly efficient | Relies on DNA repair pathways, potential for off-target effects | Sickle cell disease, beta thalassemia (approved therapies) |

| Base Editors | Chemical conversion of one DNA base to another | Does not create double-strand breaks, higher precision | Limited to specific base changes, smaller editing window | Research applications, preclinical development |

| Prime Editors | Uses reverse transcriptase to copy edited template | Precise insertions, deletions, all base changes | Larger construct size, variable efficiency | Proof-of-concept for genetic skin disorders |

| Epigenetic Editors | Modifies chromatin state without changing DNA sequence | Reversible, regulates endogenous gene expression | Potential for epigenetic drift over time | Preclinical models of cholesterol regulation |

| Transposase Systems | Precise insertion of DNA sequences without breaks | Avoids DNA repair uncertainties, seamless insertion | Early development stage, efficiency challenges in mammalian cells | Bacterial systems, potential for human gene therapy |

Experimental Methodologies in Molecular Engineering

Delivery System Engineering

The effective delivery of molecular machinery to target cells remains one of the most significant challenges in therapeutic development. Current approaches include:

Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs) LNPs have emerged as a versatile delivery platform, particularly for liver-directed therapies. These nanoscale particles form protective vesicles around nucleic acids or editing machinery and demonstrate natural tropism for hepatic tissue when administered systemically [13]. The recent demonstration that LNPs enable redosing of CRISPR therapies represents a significant advantage over viral vectors, which typically elicit immune responses that prevent repeated administration [13]. LNP formulation protocols generally involve:

- Dissolving ionizable lipids, phospholipids, cholesterol, and PEG-lipids in ethanol

- Preparing an aqueous buffer containing the nucleic acid payload (mRNA or gRNA)

- Rapid mixing of organic and aqueous phases using microfluidic devices

- Dialysis or tangential flow filtration to remove ethanol and exchange buffers

- Characterization of particle size, polydispersity, encapsulation efficiency, and in vitro/in vivo activity

Viral Vectors Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) remain the delivery vehicle of choice for certain applications despite immunogenicity concerns. Engineering efforts focus on developing novel capsids with enhanced tissue specificity and reduced pre-existing immunity. The compact size of newly discovered Cas variants (Cas12f systems) significantly expands the packaging capacity of AAV vectors, enabling delivery of more complex editing systems [14].

AI-Enhanced Experimental Design

The integration of artificial intelligence has dramatically accelerated the design and optimization of molecular engineering experiments. CRISPR-GPT, developed at Stanford Medicine, serves as an AI "copilot" that assists researchers in designing gene-editing experiments, predicting off-target effects, and troubleshooting design flaws [16]. The system leverages 11 years of published CRISPR experimental data and expert discussions to generate optimized experimental plans, significantly reducing the trial-and-error period typically required for designing effective editing strategies [16].

For tabular biological data, foundation models like TabPFN enable highly accurate predictions on small datasets, outperforming traditional gradient-boosted decision trees with substantially less computation time [17]. This approach uses in-context learning across millions of synthetic datasets to generate powerful prediction algorithms that can be applied to diverse experimental contexts from drug discovery to biomaterial design [17].

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Engineering

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Technical Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genome Editing Enzymes | Cas9, Cas12f, base editors, prime editors | Catalyze specific DNA modifications | Size, PAM requirements, editing efficiency, specificity |

| Delivery Vehicles | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), AAV vectors, lentiviral vectors | Transport editing machinery into cells | Packaging capacity, tropism, immunogenicity, production scalability |

| Guide RNA Components | crRNA, tracrRNA, sgRNA | Direct editing machinery to target sequences | Specificity, secondary structure, modification strategies |

| Detection Assays | NEXT-generation sequencing, DISCOVER-Seq, GUIDE-seq | Identify on-target and off-target editing | Sensitivity, throughput, cost, computational requirements |

| Cell Culture Models | Primary cells, iPSCs, organoids, xenograft models | Provide experimental systems for testing | Physiological relevance, scalability, genetic stability |

| Analytical Tools | CRISPR-GPT, TabPFN, off-target prediction algorithms | Design and analyze editing experiments | Data requirements, computational infrastructure, interpretability |

Visualization of Molecular Engineering Workflows

Therapeutic Genome Editing Development Pathway

Therapeutic Genome Editing Development Pathway

Molecular Machine Engineering Architecture

Molecular Machine Engineering Architecture

Emerging Applications and Future Directions

Molecular Machines for Therapeutic Applications

Beyond nucleic acid editing, molecular engineering has enabled the development of synthetic molecular machines that perform mechanical work within biological systems. Recent research demonstrates that light-activated molecular motors can influence critical cell behaviors, including triggering apoptosis in cancer cells [18]. These nanoscale machines apply mechanical forces directly within cells, fundamentally changing approaches to medical intervention by operating from inside cells rather than through external chemical agents [18].

Another innovative approach involves heat-rechargeable DNA circuits that enable sustained molecular computation without chemical waste accumulation [19]. These systems use kinetic traps that store energy when heated and release it to power molecular operations, creating reusable systems that can perform complex tasks like neural network computations or logic operations at the nanoscale [19]. Such platforms could enable long-term therapeutic interventions with single-administration treatments that remain active for extended periods.

Advanced Delivery and Sensing Systems

The integration of molecular engineering with advanced materials has produced innovative delivery and diagnostic platforms:

Self-Limiting Genetic Systems Researchers have developed CRISPR-based self-limiting genetic systems that cause female sterility while being transmitted through mosquito populations via fertile males, successfully demonstrating population elimination in laboratory settings [14]. This approach combines the efficiency of gene drive technology with containment benefits, offering potential solutions for controlling vector-borne diseases like malaria.

Advanced Diagnostic Platforms The ACRE platform represents a significant advancement in molecular diagnostics, combining rolling circle amplification with CRISPR-Cas12a to detect respiratory viruses with attomole sensitivity within 2.5 minutes [14]. This one-pot isothermal assay requires no reverse transcription or specialized equipment, enabling rapid molecular diagnostics in clinical settings with single-nucleotide specificity.

Molecular engineering has matured from theoretical concept to practical discipline, producing revolutionary technologies that are reshaping therapeutic development. The field continues to evolve at an accelerating pace, with recent advances in CRISPR systems, molecular machines, and AI-assisted design demonstrating the increasingly sophisticated capabilities available to researchers and drug development professionals. As these technologies converge, they create unprecedented opportunities to address complex diseases through precise molecular interventions.

The ongoing miniaturization of editing systems, improvement of delivery platforms, and enhancement of computational design tools suggest that molecular engineering will continue to expand its therapeutic impact. Researchers working at this intersection of biology, engineering, and computer science are well-positioned to develop the next generation of molecular solutions to humanity's most challenging health problems, fully realizing Feynman's vision of manipulating matter at the smallest possible scales.

Molecular engineering represents a foundational discipline in modern pharmaceutical research, integrating principles of chemistry, biology, and materials science to design and construct functional molecular structures. Within drug development, this field focuses on the deliberate design and synthesis of novel molecular entities with predefined biological activities and physicochemical properties. The process encompasses a systematic approach from initial computational design and chemical synthesis to comprehensive characterization and biological evaluation, forming a critical pipeline for translating theoretical molecular concepts into viable therapeutic candidates. This guide details the core technical concepts and methodologies underpinning molecular engineering, with specific emphasis on applications in pharmaceutical research and development.

Molecular Design Principles

The design phase is the critical first step in molecular engineering, where target molecules are conceptualized and modeled based on desired interactions with biological systems.

Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) and Target Engagement

Molecular design prioritizes establishing strong Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR), which are the correlations between a molecule's chemical structure and its biological activity. For a molecule to be therapeutically relevant, it must effectively engage its biological target, such as an enzyme or receptor. This involves:

- Identifying Key Interactions: Designing molecules to form specific, high-affinity interactions—such as hydrogen bonds, ionic interactions, and van der Waals forces—with the target's active site.

- Optimizing Binding Affinity: Using computational models to predict how modifications to the molecular scaffold will affect the energy and stability of the target-ligand complex.

- Ensuring Selectivity: Engineering structures to minimize off-target interactions, thereby reducing potential side effects. This often involves exploiting subtle differences between similar binding sites in related proteins.

Physicochemical Property Optimization

A potent molecule is ineffective if it cannot be delivered to its site of action. Key physicochemical properties must be optimized during the design phase [20]:

- Solubility: Adequate aqueous solubility is crucial for drug absorption and distribution. A new machine learning model, FastSolv, has been developed to predict the solubility of a given molecule in hundreds of organic solvents, accounting for the effect of temperature. This helps chemists select optimal solvents for synthesis and identify less hazardous alternatives to traditional, environmentally damaging solvents [20].

- Permeability: The ability to cross biological membranes, often predicted by properties like lipophilicity (log P) and polar surface area.

- Metabolic Stability: Designing molecules to resist rapid degradation by metabolic enzymes, thereby extending their half-life in the body.

Table 1: Key Physicochemical Properties in Molecular Design

| Property | Design Objective | Common Predictive Models |

|---|---|---|

| Aqueous Solubility | Ensure sufficient dissolution for absorption | FastSolv, Abraham Solvation Model |

| Lipophilicity (Log P) | Balance membrane permeability vs. solubility | Quantitative Structure-Property Relationship (QSPR) |

| Molecular Weight | Influence oral bioavailability; often aim for <500 g/mol | N/A |

| Hydrogen Bond Donors/Acceptors | Impact permeability and solubility; often follow the "Rule of 5" | N/A |

Synthesis and Experimental Protocols

Translating a designed structure into a tangible compound requires robust and reproducible synthetic methodologies.

Synthetic Scheme and Workflow

The synthesis of novel compounds follows a logical sequence from starting materials to the final, purified product. The workflow for synthesizing and characterizing a target molecule can be summarized as follows:

Detailed Synthesis Protocol: Sulphonyl Hydrazide Derivatives

The following protocol, derived from recent research, outlines the synthesis of sulphonyl hydrazide derivatives (R1–R5) with reported anti-inflammatory activity [21].

- Reagents: High-purity benzene, p-toluene sulphonyl chloride, 2,4-dinitrophenyl hydrazine, trimethylamine, ethyl acetate, methanol, chloroform, hexane. All reagents and solvents were dehydrated before use [21].

- Procedure:

- Reaction Setup: The synthetic reactions were carried out following a scheme as documented in prior work, leading to the development of five novel complexes, R1-R5 [21].

- Characterization: All synthesized compounds were characterized using a range of physicochemical and spectroscopic methods:

- Physicochemical Analysis: Melting points were determined using electrothermal melting point apparatus [21].

- Spectroscopic Analysis:

- Fourier-Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy: Functional groups were identified using a spectrophotometer with a wavelength range of 4000 to 400 cm⁻¹ [21].

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy: Room temperature ¹H and ¹³C NMR spectra were obtained using a Bruker Advanced Digital 300 MHz spectrometer, using DMSO as the internal reference [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Synthesis and Characterization

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application |

|---|---|

| p-Toluene Sulphonyl Chloride | Key starting material for introducing the sulphonyl group in synthesis [21]. |

| 2,4-Dinitrophenyl Hydrazine | Reactant used in the formation of hydrazide derivatives [21]. |

| Dehydrated Solvents (e.g., Methanol, Chloroform) | Used as reaction media and for purification; dehydration prevents unwanted side reactions [21]. |

| Dimethyl Sulfoxide (DMSO) | Deuterated solvent for NMR spectroscopy [21]. |

| COX-2 (Human Recombinant) | Enzyme target for in vitro anti-inflammatory evaluation [21]. |

| 5-Lipoxygenase (5-LOX, Human Recombinant) | Enzyme target for in vitro anti-inflammatory evaluation [21]. |

| Carrageenan | Agent used to induce paw edema in animal models for in vivo anti-inflammatory testing [21]. |

Characterization and Biological Evaluation

Rigorous characterization and biological screening are essential to confirm the structure and potential efficacy of synthesized compounds.

In Vitro Enzyme Inhibition Assays

To evaluate the therapeutic potential of the synthesized sulphonyl hydrazide compounds (R1–R5), they were screened for inhibitory activity against key enzymes in the inflammatory pathway: cyclooxygenase-2 (COX-2) and 5-lipoxygenase (5-LOX) [21].

Anti-Cyclooxygenase (COX-2) Assay Protocol

A standardized procedure was followed [21]:

- A 300 U/mL concentration of the human recombinant COX-2 enzyme solution was prepared.

- The enzyme solution (10 µL) was activated by adding 50 µL of a cofactor solution (containing 0.9 mM glutathione, 0.1 mM hematin, and 0.24 mM TMPD in 0.1 M Tris HCl buffer, pH 8.0) and refrigerated on ice for five minutes.

- Test samples (20 µL), at concentrations ranging from 125 to 3.91 µg/mL, were incubated with 60 µL of the activated enzyme solution for five minutes at room temperature.

- The reaction was initiated by adding 20 µL of 30 mM arachidonic acid.

- After a five-minute incubation, the absorbance was measured at 570 nm using a UV-visible spectrophotometer.

- The percentage of COX-2 inhibition was calculated, and IC₅₀ values (µM) were determined by plotting inhibition against sample concentration. Celecoxib and indomethacin were used as positive controls [21].

5-Lipoxygenase (5-LOX) Inhibitory Assay Protocol

A previously described methodology was used [21]:

- Synthesized compounds were prepared at concentrations ranging from 125 to 3.91 µg/mL.

- An enzyme solution of 10,000 U/mL 5-lipoxygenase and an 80 mM linoleic acid substrate solution were prepared.

- Test compounds were dissolved in 0.25 mL of phosphate buffer (50 mM, pH 6.3), and 0.25 µL of the lipoxygenase enzyme solution was added.

- The mixture was incubated at 25°C for 5 minutes.

- After adding 1.0 mL of the 0.6 mM linoleic acid solution and mixing, the absorbance was measured at 234 nm.

- The percentage inhibition was calculated, and IC₅₀ values were determined. Zileuton was used as a reference standard [21].

Signaling Pathways and Molecular Mechanisms

Inflammation involves the release of arachidonic acid from cell membrane phospholipids. This acid is subsequently converted into pro-inflammatory prostaglandins and thromboxane A₂ via the COX-2 pathway and into leukotrienes via the 5-LOX pathway [21]. Inhibiting both pathways simultaneously can provide broader anti-inflammatory effects while potentially reducing adverse effects associated with targeting only one pathway [21]. The following diagram illustrates this key inflammatory pathway and the site of action for the inhibitors:

Data Analysis and Validation

The results from in vitro and in vivo studies must be rigorously analyzed to validate the efficacy and mechanism of action of the synthesized compounds.

Table 3: Quantitative Results from In Vitro Enzyme Inhibition Assays

| Compound | COX-2 Inhibition IC₅₀ (µM) | 5-LOX Inhibition IC₅₀ (µM) | Cytotoxicity (Hek293 cell line) |

|---|---|---|---|

| R1 | Significant activity (P < 0.05) [21] | Significant activity (P < 0.05) [21] | Evaluated using MTT assay [21] |

| R2 | Significant activity (P < 0.05) [21] | Significant activity (P < 0.05) [21] | Evaluated using MTT assay [21] |

| R3 | 0.84 [21] | 0.46 [21] | Evaluated using MTT assay [21] |

| R4 | Significant activity (P < 0.05) [21] | Significant activity (P < 0.05) [21] | Evaluated using MTT assay [21] |

| R5 | Significant activity (P < 0.05) [21] | Significant activity (P < 0.05) [21] | Evaluated using MTT assay [21] |

| Reference Drug (e.g., Celecoxib) | Used as positive control [21] | N/A | N/A |

- In Vivo Anti-inflammatory Potential: The compounds were further evaluated in vivo for anti-inflammatory potential using a model like carrageenan-induced paw edema, followed by an acute toxicity study. Compound R3, for instance, led to a statistically significant decrease in paw edema from the 1st to the 5th hour after carrageenan injection [21].

- Mechanism of Action: To confirm the anti-inflammatory pathway, the most potent compounds were evaluated against various phlogistic mediators, including histamine, bradykinin, leukotrienes, and prostaglandins [21].

- Computational Validation (Molecular Docking): The binding strategies of the compounds were identified using molecular docking assays (e.g., using Molecular Operating Environment - MOE software). This involved examining the interaction between the compounds and the amino acid residues in the binding pockets of the COX-2 and 5-LOX enzymes. Compound R3 showed a strong binding affinity with the targeted receptors, providing a structural rationale for its potent inhibitory activity [21].

The integrated process of molecular design, synthesis, and characterization forms the cornerstone of molecular engineering in pharmaceutical applications. The case study of sulphonyl hydrazide derivatives demonstrates a complete research pipeline: starting from rational design aimed at inhibiting key inflammatory targets (COX-2 and 5-LOX), proceeding through a well-defined synthetic protocol, and culminating in comprehensive characterization and biological evaluation. The convergence of experimental data—from physicochemical analysis and in vitro enzyme kinetics to in vivo efficacy and computational docking studies—provides a robust framework for validating new molecular entities. This systematic approach is critical for advancing drug discovery, enabling researchers to efficiently translate molecular concepts into promising therapeutic candidates with well-understood mechanisms of action.

Molecular engineering represents a fundamental shift in scientific research, moving beyond traditional disciplinary silos to embrace an integrative approach that combines chemistry, biology, physics, and materials science. This interdisciplinary framework enables engineers and scientists to address complex biological problems that are intractable through single-discipline approaches. The field operates on the principle that biological systems can be understood and manipulated using engineering principles, creating a powerful convergence of knowledge and methodologies [22]. This paradigm has become particularly transformative in pharmaceutical research, where molecular engineering provides novel tools for drug discovery, synthesis, and development through the rational design of biological systems [23].

The interdisciplinary nature of molecular engineering mirrors that of biophysics, which similarly bridges multiple scientific domains to unravel life's mysteries. Biophysics integrates physics, biology, chemistry, and mathematics to study living systems across multiple scales—from individual molecules to entire ecosystems [22]. This convergence of disciplines creates what might be termed a "super-powered toolkit" for investigating biological phenomena, enabling breakthroughs that were previously unimaginable through singular disciplinary lenses. The engineer's view of biology transforms cells into industrial biofactories and biological components into programmable devices, fundamentally reorienting approaches to drug discovery and development [23].

Theoretical Foundations: Core Principles and Quantitative Frameworks

Contributions of Individual Disciplines

The interdisciplinary framework of molecular engineering draws upon distinct but complementary contributions from its constituent fields. Physics provides the fundamental laws governing matter and energy behavior at molecular and cellular levels, including thermodynamic principles that dictate biomolecular interaction energetics, kinetic theories that describe reaction rates and enzyme catalysis, and mechanical models that explain cellular and tissue properties [22]. Biology contributes essential knowledge of living systems—their structures, functions, and evolutionary adaptations—providing the necessary biological context for molecular engineering problems and ensuring the biological relevance of engineered solutions [22]. Chemistry offers understanding of biomolecular chemical properties and interactions, which proves crucial for studying the molecular basis of biological processes and designing effective molecular interventions [22]. Materials science provides principles for designing and characterizing novel biomaterials with tailored properties for specific applications, particularly in drug delivery and biomedical devices.

Mathematics serves as the unifying language, supplying tools for quantitative analysis, modeling, and simulation of biological systems. Differential equations describe continuous changes in biological systems over time; probability theory models stochastic processes like gene expression and ion channel gating; and graph theory represents complex biological networks including metabolic pathways and signaling cascades [22]. These mathematical frameworks enable the prediction of system behaviors in response to perturbations, a critical capability for both understanding natural systems and designing synthetic ones.

Quantitative Data Framework for Interdisciplinary Research

Table 1: Key Physical Principles and Their Applications in Molecular Engineering

| Physical Principle | Governing Equations | Biological Applications | Quantitative Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermodynamics | ΔG = ΔH - TΔS | Protein folding, Membrane transport | Binding constants (Kd), Enthalpy (ΔH), Entropy (ΔS) |

| Kinetics | d[A]/dt = -k[A] | Enzyme catalysis, Signal transduction | Rate constants (k), Activation energy (Ea) |

| Mechanics | F = ks·Δx | Cellular adhesion, Tissue elasticity | Elastic modulus (E), Viscosity (η), Adhesion strength |

| Diffusion | ∂C/∂t = D∇²C | Molecular transport, Gradient formation | Diffusion coefficient (D), Concentration gradient (∇C) |

Table 2: Spectroscopic and Analytical Techniques in Molecular Engineering

| Technique | Physical Basis | Spatial Resolution | Information Obtained | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| X-ray Crystallography | X-ray diffraction by crystals | Atomic (0.1-1 Å) | 3D atomic structure | Protein structure determination [22] |

| NMR Spectroscopy | Magnetic properties of atomic nuclei | Atomic (0.1-1 nm) | Structure, dynamics, interactions | Biomolecules in solution [22] |

| Cryo-EM | Electron scattering | Near-atomic (1-3 Å) | 3D structure of complexes | Large biomolecular assemblies [22] |

| FT-IR Spectroscopy | Molecular vibrations | 1-10 μm | Chemical bonding, conformation | Protein secondary structure [24] |

Methodological Integration: Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Molecular Biology and Genetic Engineering Protocols

The experimental foundation of molecular engineering relies heavily on standardized molecular biology protocols that enable precise genetic manipulation. DNA restriction and analysis form the cornerstone of genetic engineering, with restriction enzyme digestion protocols allowing specific DNA cleavage at recognition sites [25]. These reactions typically utilize 0.1-2 μg DNA, 1-2 units of restriction enzyme, and appropriate reaction buffers, incubated at 37°C for 1-2 hours. The resulting fragments are analyzed by agarose gel electrophoresis (0.8-2% gels in TAE or TBE buffer) with ethidium bromide or SYBR Safe staining for visualization under UV light [25].

Nucleic acid amplification and sequencing protocols enable gene cloning and analysis. Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) protocols employ thermal cycling (95°C denaturation, 50-65°C annealing, 72°C extension) with DNA template, primers, dNTPs, and thermostable DNA polymerase in appropriate buffer solutions [25]. Modern sequencing approaches, including next-generation sequencing (NGS) platforms, provide comprehensive genetic information that informs engineering decisions. Molecular cloning protocols integrate these techniques through ligation reactions (using T4 DNA ligase with vector and insert DNA at specific ratios) followed by bacterial transformation (chemical or electroporation methods) with selection on antibiotic-containing media [25]. These fundamental protocols provide the genetic manipulation toolkit essential for constructing synthetic biological systems.

Protein Engineering and Analysis Methods

Protein engineering methodologies enable the design and optimization of molecular components for specific functions. Protein detection and analysis protocols include SDS-PAGE for molecular weight determination using discontinuous buffer systems with stacking and resolving gels, followed by Western blotting for specific antigen detection using primary and secondary antibodies with chemiluminescent or colorimetric substrates [25]. ELISA protocols (direct, indirect, sandwich) provide quantitative protein detection through antibody-antigen interactions with enzymatic signal amplification [25].

Protein purification protocols employ various chromatographic techniques based on specific properties. Affinity purification utilizes tags (e.g., His-tag, GST-tag) with corresponding resin systems (Ni-NTA for His-tagged proteins) with binding, washing, and elution steps under native or denaturing conditions [25]. Protein quantification employs multiple assay types: absorbance assays (A280 for aromatic residues, A205 for peptide bonds) and colorimetric assays (Bradford, Lowry, BCA) based on different color formation mechanisms with bovine serum albumin (BSA) standards for calibration [25]. These protein methodologies enable the characterization and optimization of engineered enzymes and structural proteins.

Computational and Modeling Approaches

Computational methods provide the mathematical framework for analyzing and predicting the behavior of engineered biological systems. Molecular dynamics simulations apply Newton's laws of motion and empirical force fields to predict biomolecular motion and interactions, providing atomic-level insights into dynamic processes [22]. Quantum mechanics calculations determine electronic structure and reactivity for enzyme active sites and photosynthetic pigments, enabling precise engineering of catalytic properties [22]. Bioinformatics algorithms analyze large-scale biological data—genomic sequences, protein structures, gene expression profiles—to extract meaningful patterns and identify engineering targets [22].

These computational approaches operate across multiple scales, from atomic-level interactions to system-level behaviors, and require specialized infrastructure for implementation. The OU Supercomputing Center for Education and Research represents the type of computational resources needed for these analyses, providing advanced computing capabilities for science and engineering research [24]. Chemical informatics resources, including comprehensive chemometrics and specialized spectral databases, support the analysis and interpretation of complex molecular data [24].

Experimental Workflow: Integrated Research Pipeline

Diagram 1: Molecular Engineering Workflow

Research Toolkit: Essential Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Engineering Experiments

| Reagent/Material | Composition/Properties | Function in Experiments | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Restriction Enzymes | Endonucleases with specific recognition sequences | DNA cleavage at specific sites | Molecular cloning, plasmid construction [25] |

| DNA Ligases | Enzymes catalyzing phosphodiester bond formation | Joining DNA fragments | Vector-insert ligation in cloning [25] |

| Polymerases | Enzymes synthesizing DNA polymers | DNA amplification and synthesis | PCR, cDNA synthesis, sequencing [25] |

| Plasmids | Circular double-stranded DNA vectors | Gene cloning and expression | Recombinant protein production, genetic circuits [25] |

| Agarose | Polysaccharide from seaweed | Matrix for nucleic acid separation | Gel electrophoresis of DNA/RNA [25] |

| Antibodies | Immunoglobulins with specific binding | Protein detection and purification | Western blot, ELISA, immunofluorescence [25] |

| Chromatography Resins | Matrices with specific functional groups | Biomolecule separation | Protein purification (affinity, ion exchange) [25] |

| Cell Culture Media | Balanced nutrient solutions | Cell growth and maintenance | Mammalian cell culture, bacterial growth [25] |

Interdisciplinary Signaling in Synthetic Biology

Diagram 2: Synthetic Biology Signaling

Applications in Pharmaceutical Sciences: Synthetic Biology for Drug Discovery

The interdisciplinary approach of molecular engineering finds particularly powerful application in pharmaceutical sciences, where synthetic biology is reorienting the field of drug discovery. Synthetic biology applies engineering principles to biological systems, creating engineered genetic circuits that support various drug development stages [23]. These approaches address the high attrition rate in drug development, where approximately 95% of drugs tested in Phase I fail to reach approval, by creating more predictive models and targeted therapies [23].

A landmark achievement in this field was the bioproduction of artemisinin by engineered microorganisms, representing a tour de force in protein and metabolic engineering [23]. This success demonstrated the potential of synthetic cells as biofactories for complex natural products that are difficult to produce by traditional chemical synthesis. Beyond bioproduction, engineered genetic circuits serve as cell-based screening platforms for both target-based and phenotypic-based drug approaches, decipher disease mechanisms, elucidate drug mechanisms of action, and study cell-cell communication within bacterial consortia [23]. These applications address fundamental challenges in drug development, including drug resistance and toxicity.

Mining Natural Product Space Through Engineering

Natural products have provided countless therapeutic agents throughout human history, including antibiotics, antifungals, antitumors, immunosuppressants, and cholesterol-lowering agents [23]. Major classes of therapeutically relevant natural products include polyketides, non-ribosomal peptides (NRPs), terpenoids, isoprenoids, alkaloids, and flavonoids [23]. The difficulty in resynthesizing these complex molecules initially limited their pharmaceutical development, but synthetic biology approaches have enabled in-depth exploration of this rich chemical space.

The foundation for modern natural product engineering was established in the 1990s with the discovery that antibiotics like erythromycin are synthesized by giant biosynthetic units comprising multiple protein modules from single gene clusters [23]. These biosynthetic units can be isolated, genetically manipulated, and implemented in host organisms to produce natural product derivatives [23]. Large-scale genome and metagenome sequencing of microorganisms, coupled with bioinformatics tools like Secondary Metabolite Unknown Regions Finder (SMURF) and antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell (antiSMASH), has dramatically expanded the discovery of such biosynthetic gene clusters [23]. When these clusters remain cryptic or silent under standard culture conditions, synthetic biology approaches can activate expression through designed synthetic transcription factors, ligand-controlled aptamers, riboswitches, or "knock-in" promoter replacement strategies [23].

Molecular Engineering in Drug Resistance and Toxicity Studies

Synthetic biology approaches provide powerful tools for addressing two fundamental challenges in drug development: toxicity and drug resistance. Engineered genetic circuits can be designed to detect and respond to toxic compounds, creating cellular sentinels for toxicity screening [23]. Similarly, synthetic quorum sensing systems can model population-level behaviors in bacterial communities, providing insights into antibiotic persistence and resistance mechanisms [23]. These approaches enable researchers to study complex biological phenomena in controlled, engineered systems that are more predictive than traditional models.

Protein engineering, as another key tool of synthetic biology, enables the optimization of enzymatic properties for pharmaceutical applications. Site-directed mutagenesis can enhance the regio- or stereospecificity of enzymes, increase ligand binding constants, or select between enzyme isoforms [23]. Directed evolution approaches apply selective pressure to engineer enzymes with novel functions, while mutational biosynthesis (mutasynthesis) forces supplemented substrate analogs to be processed by engineered enzymes through selective evolution [23]. These protein engineering strategies generate biological components with optimized properties for pharmaceutical applications.

Educational and Research Infrastructure

The interdisciplinary nature of molecular engineering requires correspondingly integrated educational and research programs. The University of Chicago's Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering exemplifies this approach through its PhD program, which accepts students with bachelor's degrees in STEM fields and explicitly does not require GRE scores for admission [26]. The program organizes research around thematic areas including Materials for Sustainability, Immunoengineering, and Quantum Science and Engineering, with admissions decisions released by these research areas [26].

At the undergraduate level, Research Experiences for Undergraduates (REU) programs provide immersive interdisciplinary research opportunities. The University of Chicago's REU in molecular engineering offers undergraduate students from non-research institutions the opportunity to work in PME faculty research labs on projects spanning self-assembling polymers for nanomanufacturing, immune system engineering, quantum material development, and molecular-level energy storage and harvesting [27]. These programs specifically aim to broaden the STEM pipeline for students from institutions with limited research opportunities [27].

The interdisciplinary integration of chemistry, biology, physics, and materials science within molecular engineering represents a paradigm shift in scientific research, enabling unprecedented capabilities to understand and manipulate biological systems. This convergence of disciplines creates a holistic framework for addressing complex challenges in pharmaceutical development, materials design, and therapeutic innovation. As molecular engineering continues to evolve, its interdisciplinary nature will likely deepen, incorporating additional fields such as computer science, artificial intelligence, and advanced robotics. The continued development of this interdisciplinary approach promises to accelerate the translation of basic research findings into practical applications, from novel therapeutic agents to advanced biomaterials and diagnostic technologies. Through its integrative framework, molecular engineering exemplifies the power of interdisciplinary approaches to drive scientific innovation and address complex societal challenges.

Methodologies and Transformative Applications in Medicine and Technology

Molecular engineering operates at the intersection of chemistry, physics, and biology, focusing on the deliberate design and manipulation of molecules at the atomic and molecular scale to create materials and systems with specific, user-defined properties [28]. This discipline represents a fundamental shift from traditional engineering, which deals with bulk materials, toward the construction of functional devices and solutions at the nanoscale [28]. The field is being transformed by a powerful triad of core techniques: computational modeling, which predicts molecular behavior; de novo design, which creates entirely new proteins and molecules from first principles; and directed evolution, which optimizes these designs in the laboratory. These methodologies enable researchers to solve problems in ways previously unimaginable, with applications spanning healthcare, energy, and biotechnology [29] [28]. This technical guide examines the principles, methodologies, and integration of these techniques, providing a framework for their application in advanced research and development, particularly in drug development and therapeutic protein engineering.

Computational Modeling: The Predictive Foundation

Computational modeling provides the theoretical and predictive foundation for modern molecular engineering. It transforms the design of proteins and molecules from a trial-and-error process into a rational, physics-based endeavor.

Key Principles and Methodologies

At its core, computational protein design is formulated as an optimization problem: given a desired structure or function, design methods seek to predict an optimal sequence that stably adopts that structure and performs that function [29]. The challenge is navigating the vast sequence space; for a small 100-residue protein, there are approximately 10^130 possible sequences, making exhaustive sampling impossible [29]. Advanced search algorithms are therefore required to efficiently explore this space.