Maxwell Relations Decoded: Derivation, Meaning, and Applications in Biomedical Thermodynamics

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Maxwell relations, a cornerstone of equilibrium thermodynamics.

Maxwell Relations Decoded: Derivation, Meaning, and Applications in Biomedical Thermodynamics

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide to Maxwell relations, a cornerstone of equilibrium thermodynamics. Beginning with their elegant derivation from exact differentials and fundamental thermodynamic potentials, we explore their profound physical meaning in connecting measurable system properties. The content details step-by-step derivation methodologies and their crucial applications in fields like drug solubility prediction, protein-ligand binding, and phase equilibrium analysis in pharmaceutical development. We address common pitfalls in derivation and application, offer optimization strategies for complex systems, and validate the relations against experimental data and computational models. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes theoretical foundations with practical implementation, highlighting how Maxwell relations serve as indispensable tools for extracting non-measurable thermodynamic data and optimizing bioprocesses in biomedical research.

Unlocking Maxwell Relations: The Cornerstone of Thermodynamic Connections

Theoretical Foundation and Biomedical Context

Maxwell relations are a cornerstone of equilibrium thermodynamics, derived from the symmetry of second derivatives of thermodynamic potentials. In biomedical systems, these relations provide a powerful, indirect means to relate measurable quantities (e.g., thermal expansion, compressibility, heat capacity) to parameters that are difficult or impossible to measure directly within living tissues or delicate biochemical equilibria. This framework is integral to a broader thesis on the derivation and physical meaning of Maxwell relations, demonstrating their translation from abstract mathematical elegance to practical tools in physiology, biophysics, and drug development.

Core Maxwell Relations and Their Biomedical Interpretations

The four primary relations for a simple compressible system are:

| Thermodynamic Potential | Maxwell Relation | Potential Biomedical Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy (U) | ( \left( \frac{\partial T}{\partial V} \right)S = -\left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial S} \right)V ) | Relates adiabatic temperature change to entropy-driven pressure shifts (e.g., in rapid muscle contraction). |

| Enthalpy (H) | ( \left( \frac{\partial T}{\partial P} \right)S = \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial S} \right)P ) | Connects temperature change under pressure to entropic volume change (e.g., in vascular response). |

| Helmholtz Free Energy (F) | ( \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)T = \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial T} \right)V ) | Most used: Links thermal pressure coefficient to entropy change upon expansion (e.g., protein unfolding, membrane elasticity). |

| Gibbs Free Energy (G) | ( \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial P} \right)T = -\left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T} \right)P ) | Crucial for drug binding: Relates thermal expansion to pressure dependence of entropy (e.g., in binding cavity dynamics). |

Quantitative Data: Thermodynamic Parameters in Biophysical Systems

The following table summarizes key measurable parameters interconnected via Maxwell relations in biomedical contexts.

Table 1: Experimentally Determined Thermodynamic Parameters for Biological Processes

| Process / System | Isobaric Thermal Expansion Coefficient, α (K⁻¹) | Isothermal Compressibility, κ_T (Pa⁻¹) | Constant Pressure Heat Capacity, C_p (J·mol⁻¹·K⁻¹) | Derived Relation (via Maxwell) | Experimental Method |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Protein Unfolding (Lysozyme) | ~8.0 x 10⁻⁴ (unfolded state) | ~1.2 x 10⁻¹⁰ (unfolded state) | ~16,000 (∆C_p upon unfolding) | ( \left( \frac{\partial \Delta V}{\partial T} \right)P = -\left( \frac{\partial \Delta S}{\partial P} \right)T ) | Pressure Perturbation Calorimetry (PPC) |

| Lipid Bilayer (DPPC) | ~3.5 x 10⁻³ (gel to fluid) | ~7.0 x 10⁻¹⁰ (fluid phase) | ~40 (per mol lipid) | ( \left( \frac{\partial \Delta H}{\partial P} \right)T = \Delta V - T\left( \frac{\partial \Delta V}{\partial T} \right)P ) | Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) & Ultrasonic Velocimetry |

| Drug Binding (Small mol. to protein) | N/A (∆V of binding ~ -10 to -100 cm³/mol) | N/A | Can be positive or negative | ( \left( \frac{\partial \Delta S}{\partial P} \right)T = -\left( \frac{\partial \Delta V}{\partial T} \right)P ) | Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) at varied T & P |

| Cellular Volume Regulation | ~0.001 - 0.01 (effective) | ~10⁻¹⁰ - 10⁻⁹ | N/A | ( \left( \frac{\partial π}{\partial T} \right)V = \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)T ) (π = osmotic pressure) | Coulter Counter / Fluorescence Microscopy with osmotic stress |

Experimental Protocols for Key Measurements

Protocol: Pressure Perturbation Calorimetry (PPC) for Protein Solutions

Objective: Determine the partial molar thermal expansion coefficient (α) and volume change (∆V) of protein unfolding. Principle: Measures the heat required to maintain temperature equilibrium during small, rapid pressure jumps. This heat is directly related to ( \left( \frac{\partial \alpha}{\partial T} \right)_P ), integrable to obtain α(T). Combined with DSC data, it yields ∆V(T) via Maxwell relations. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare protein solution (e.g., 1-2 mg/mL lysozyme in chosen buffer) and dialyze exhaustively. Use dialysate as reference.

- Instrument Calibration: Perform baseline scan with matched buffer in both cells.

- Pressure Jump Experiment: a. Set instrument (e.g., MicroCal PPC) to desired scanning temperature (e.g., 10°C to 80°C). b. Apply repeated pressure jumps (e.g., ±5 bar) at each temperature point. c. Record the heat flow (dQ/dt) required to maintain thermal equilibrium after each jump.

- Data Analysis: a. Calculate the coefficient ( \frac{dQ}{dP} ) / (T * Vcell) at each T. b. This equals ( -T \left( \frac{\partial \alpha}{\partial T} \right)P ). c. Integrate with respect to T to obtain α(T) for native and denatured states. d. Combine with DSC unfolding curve to calculate the volume change of unfolding, ∆V(T).

Protocol: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for Binding Thermodynamics

Objective: Determine Gibbs free energy (∆G), enthalpy (∆H), entropy (∆S), and heat capacity change (∆C_p) of a drug-target interaction. Principle: Directly measures heat released or absorbed upon incremental injection of a ligand into a protein solution. A full thermodynamic profile is obtained by performing experiments at multiple temperatures. Procedure:

- Sample Preparation: Precisely match buffer conditions for protein and ligand solutions via dialysis or buffer exchange. Degas samples.

- Instrument Setup: Load protein solution (e.g., 20 µM) into the sample cell. Load ligand solution (e.g., 200 µM) into the syringe.

- Titration Experiment: a. Set temperature (e.g., 25°C). Perform initial injection (0.4 µL), followed by 18-28 injections (e.g., 2-3 µL each) with 180-240s spacing. b. Stir continuously. Record µcal/sec of heat flow. c. Repeat identical experiment at 3-4 other temperatures (e.g., 15°C, 20°C, 30°C, 35°C).

- Data Analysis: a. Integrate peaks to obtain total heat per injection. b. Fit binding isotherm to obtain ∆H and binding constant Ka (hence ∆G = -RT lnKa) at each T. c. Calculate ∆S at each T: ∆S = (∆H - ∆G)/T. d. Plot ∆H vs. T; slope is ∆Cp. e. Apply Maxwell Relation: Use ∆Cp and the relation ( \left( \frac{\partial \Delta V}{\partial T} \right)P = -\Delta \alpha = -\frac{\Delta Cp}{T \cdot \PiT} ) (where ΠT is a pressure factor) to estimate the temperature dependence of the binding volume change.

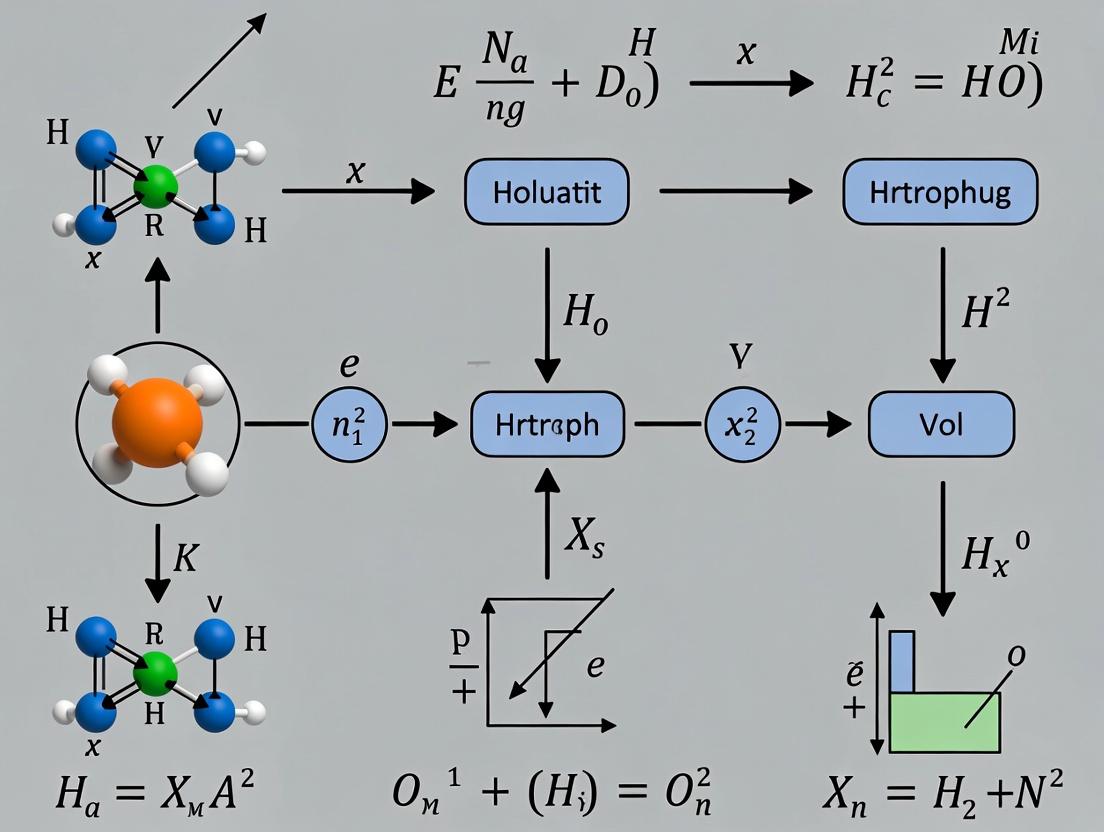

Visualizing Thermodynamic Pathways and Relationships

Thermodynamic Inference Workflow

Maxwell Relation as a Connector

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Thermodynamic Studies in Biomedicine

| Item / Reagent | Function / Role | Example Product / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| High-Precision Calorimeter | Measures heat changes (∆H, C_p) from binding, folding, or phase transitions. | MicroCal PEAQ-ITC, Malvern DSC. |

| Pressure Perturbation Cell | Applies rapid, small pressure jumps to measure thermal expansion coefficient. | MicroCal PPC accessory for VP-DSC. |

| Ultrasonic Velocimeter | Measures speed of sound in solutions to determine adiabatic compressibility. | ResoScan System (TF Instruments). |

| Stable, Dialyzable Buffer Systems | Minimizes heats of dilution in ITC; ensures perfect solvent matching. | Phosphate, Tris, HEPES at ≥20 mM. |

| Reference Proteins (for Calibration) | Validate instrument performance and data analysis protocols. | RNase A, Lysozyme (for unfolding). |

| High-Purity Ligands/Inhibitors | Ensure observed heat signals originate solely from specific binding events. | ≥98% purity, verified by HPLC/MS. |

| Dialysis Cassettes/Cartridges | For exhaustive buffer matching of protein and ligand samples. | Slide-A-Lyzer (10kDa MWCO). |

| Degassing Station | Removes dissolved gases to prevent bubbles in calorimetry cells. | ThermoVac accessory or sonicator. |

Within the broader research on deriving and interpreting Maxwell relations, the concepts of exact differentials and state functions constitute the essential mathematical and thermodynamic bedrock. This guide details their technical foundation, experimental relevance in biophysical chemistry, and their critical role in linking measurable quantities for researchers in drug development.

Mathematical and Thermodynamic Foundations

In thermodynamics, a state function (e.g., internal energy U, enthalpy H, Gibbs free energy G) is a property whose value depends solely on the current state of the system (pressure P, volume V, temperature T, composition N), not on the path taken to reach that state. The differential of a state function is called an exact differential.

For a function Z(x,y), the differential dZ = M dx + N dy is exact if:

- M and N are partial derivatives: M = (∂Z/∂x)_y, N = (∂Z/∂y)_x.

- It satisfies the Euler reciprocity relation: (∂M/∂y)_x = (∂N/∂x)_y.

The path-independence of state functions implies that the cyclic integral of their exact differential is zero: ∮ dZ = 0.

Core State Functions and Their Differentials

The four primary thermodynamic potentials and their exact differentials are:

Table 1: Fundamental Thermodynamic Potentials and Exact Differentials

| State Function & Symbol | Defining Equation | Exact Differential (Natural Variables) | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy (U) | - | dU = T dS – P dV + Σ μᵢ dNᵢ | Fundamental relation, closed systems. |

| Enthalpy (H) | H = U + PV | dH = T dS + V dP + Σ μᵢ dNᵢ | Constant-pressure processes (e.g., calorimetry). |

| Helmholtz Free Energy (A) | A = U – TS | dA = –S dT – P dV + Σ μᵢ dNᵢ | Constant-temperature, constant-volume systems. |

| Gibbs Free Energy (G) | G = H – TS | dG = –S dT + V dP + Σ μᵢ dNᵢ | Phase equilibria, drug binding, constant T & P. |

Where: T=Temperature, S=Entropy, P=Pressure, V=Volume, μᵢ=Chemical potential of component i, Nᵢ=Mole number of i.

Experimental Protocols: Measuring State Function Changes

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for ΔG, ΔH, ΔS

ITC directly measures heat exchange (q) upon incremental binding of a drug (ligand) to a target (protein), providing direct access to ΔH.

Protocol:

- Preparation: Fill the sample cell (≈200 µL) with target protein solution (e.g., 10-100 µM in phosphate buffer). Fill the syringe with ligand solution (10x the protein concentration).

- Equilibration: Equilibrate both cells at constant temperature (e.g., 25°C) with constant stirring (≈750 rpm).

- Titration: Perform 10-20 automated injections of ligand (e.g., 2 µL each) at set time intervals (120-240 s). The instrument measures the heat flow (µJ/s) required to maintain zero temperature difference between sample and reference cells.

- Data Analysis: The integrated heat per injection is fit to a binding model (e.g., single-site) to obtain the binding constant K_b (from which ΔG = –RT lnK_b), ΔH (from the heat), and stoichiometry n. ΔS is then calculated via ΔG = ΔH – TΔS.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) for ΔH of Denaturation

DSC measures the heat capacity (C_P) of a protein solution as a function of temperature, detecting enthalpic changes during thermal denaturation.

Protocol:

- Loading: Precisely load matched protein and reference (buffer) solutions into the sample and reference cells (≈500 µL).

- Scanning: Ramp temperature at a constant rate (e.g., 1°C/min) across a range spanning the native and denatured states (e.g., 20-120°C).

- Baseline & Analysis: Subtract the buffer-buffer reference scan. The area under the excess heat capacity peak (ΔC_P) versus temperature curve yields the enthalpy of denaturation, ΔH_den.

Visualization of Conceptual and Experimental Relationships

Title: From State Functions to Maxwell Relations

Title: ITC Yields ΔG, ΔH, ΔS for Drug Binding

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Thermodynamic Binding Studies

| Item | Function & Explanation |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Buffer Salts (e.g., phosphate, HEPES, Tris) | To maintain constant pH and ionic strength, ensuring reproducible ligand-target interactions and minimizing nonspecific binding heats. |

| Ultrapure Water (≥18.2 MΩ·cm) | Prevents artifacts in calorimetry from impurities that can affect baseline stability and cause signal noise. |

| Lyophilized Target Protein (≥95% purity) | High purity is critical for accurate stoichiometry determination in ITC and clean transitions in DSC. |

| Analytical Grade Ligand/Drug Compound | Precise knowledge of concentration and purity (via NMR, HPLC) is essential for accurate K_b and ΔH calculation. |

| ITC Cleaning Solution (e.g., 20% Contrad 70, 5% acetic acid) | Ensures complete decontamination of the calorimeter cell between experiments, preventing carryover and baseline drift. |

| Reference Buffer (Exact match to sample buffer) | For DSC and ITC, the reference must be identical to the sample buffer except for the macromolecule, allowing subtraction of dilution/mixing heats. |

| Degassing Unit | Removes dissolved gases from solutions prior to loading into calorimeters, preventing bubble formation that disrupts heat measurement. |

This document is a foundational component of a broader thesis research on the derivation and physical meaning of Maxwell relations. The four thermodynamic potentials—Internal Energy (U), Enthalpy (H), Helmholtz Free Energy (F), and Gibbs Free Energy (G)—are the cornerstones from which these relations naturally arise via the symmetry of second derivatives. Understanding their definitions, natural variables, and physical interpretations is prerequisite to appreciating Maxwell relations as powerful tools for connecting measurable properties in materials science, chemistry, and drug development.

The Four Potentials: Definitions and Natural Variables

Each potential is a Legendre transform of the internal energy, designed to be minimized at equilibrium under specific experimental constraints. Their natural variables are critical for deriving correct differential forms and subsequent Maxwell relations.

Table 1: Definitions and Natural Variables of the Four Key Potentials

| Thermodynamic Potential | Symbol & Common Name | Defining Relation | Natural Variables | Equilibrium Condition |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy | U | Fundamental | S, V | dU = 0 (S, V constant) |

| Enthalpy | H | H = U + PV | S, P | dH = 0 (S, P constant) |

| Helmholtz Free Energy | F (or A) | F = U - TS | T, V | dF ≤ 0 (T, V constant) |

| Gibbs Free Energy | G | G = U + PV - TS = H - TS | T, P | dG ≤ 0 (T, P constant) |

Differential Forms and Maxwell Relation Derivation

The differential form of each potential, expressed in terms of its natural variables, provides the direct link to Maxwell relations. For a simple compressible system:

Internal Energy: dU = TdS - PdV

- From the symmetry of exact differentials (∂²U/∂S∂V = ∂²U/∂V∂S), we obtain the first Maxwell relation: (∂T/∂V)ₛ = –(∂P/∂S)ᵥ.

Enthalpy: dH = TdS + VdP

- Symmetry yields: (∂T/∂P)ₛ = (∂V/∂S)ₚ.

Helmholtz Free Energy: dF = -SdT - PdV

- Symmetry yields: (∂S/∂V)ₜ = (∂P/∂T)ᵥ. This is frequently used to relate thermal and mechanical equations of state.

Gibbs Free Energy: dG = -SdT + VdP

- Symmetry yields: –(∂S/∂P)ₜ = (∂V/∂T)ₚ. This connects isothermal compressibility and thermal expansion.

The logical derivation pathway from the potentials to the full set of Maxwell relations is depicted below.

Diagram 1: Derivation Path from Potentials to Maxwell Relations

Physical Interpretation and Relevance to Drug Development

Table 2: Physical Interpretation and Application Context

| Potential | Key Physical Meaning | Experimental Constraint | Application Example in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| U | Total energy of the system. | Adiabatic, constant volume. | Less common in solution-phase biochemistry. |

| H | Heat content at constant pressure. | Constant pressure (open to atmosphere). | Directly measured in calorimetry (e.g., ITC). Enthalpy change (ΔH) quantifies binding heat. |

| F | Maximum reversible work obtainable at constant T, V. | Constant temperature and volume. | Useful in statistical mechanics; models protein folding in a fixed volume. |

| G | Maximum non-PV work obtainable at constant T, P. | Constant temperature and pressure. | Central to drug binding. ΔG° = -RTlnKₐ determines binding affinity (Kₐ). ΔG = ΔH - TΔS. |

The relationship between these potentials and the measurable thermodynamic parameters governing drug binding is illustrated below.

Diagram 2: Linkage of Potentials to Drug Binding Metrics

Experimental Protocol: Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

ITC is the premier experiment for simultaneously determining ΔH, ΔG, and ΔS for molecular interactions (e.g., drug-target binding).

Protocol:

- Preparation: Precisely degas all buffer solutions to prevent air bubble formation in the instrument. Prepare ligand (drug compound) in syringe at 10-20x the concentration of the macromolecule (protein target) in the cell. Both must be in identical buffer.

- Instrument Setup: Load the sample cell with protein solution (typically 200 µL). Fill the reference cell with Milli-Q water or buffer. Load the syringe with ligand solution. Set the target temperature (e.g., 25°C or 37°C).

- Titration Programming: Define the number of injections (typically 19), injection volume (e.g., 2 µL first, then 10-15 µL), injection duration (e.g., 4 s), spacing between injections (e.g., 180 s), and reference power (e.g., 10 µcal/s).

- Data Acquisition: Start the experiment. The instrument injects ligand while adding or removing heat from the sample cell to maintain temperature equality with the reference cell. The power (µcal/s) required over time is recorded.

- Data Analysis: Integrate each injection peak to obtain the total heat per mole of injectant. Fit the binding isotherm (heat vs. molar ratio) to a suitable model (e.g., one-set-of-sites). The fit directly yields the binding constant Kᵦ (=1/K_d), the enthalpy change ΔH, and the stoichiometry n. Calculate ΔG = -RT lnKᵦ and ΔS = (ΔH - ΔG)/T.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Thermodynamic Binding Studies

| Item | Function & Importance |

|---|---|

| High-Purity, Lyophilized Protein Target | The biological macromolecule of interest (e.g., kinase, protease). Purity >95% is essential to avoid spurious binding signals. |

| Characterized Small Molecule Ligand | Drug candidate or substrate. Must have known molecular weight, high purity, and solubility in assay buffer. |

| Match-ITC Buffer Kit | A set of buffers (e.g., PBS, Tris, HEPES) with matching chemical composition for precise preparation of protein and ligand samples. Eliminates heat of dilution from buffer mismatch. |

| ITC Cleaning Solution | A proprietary detergent solution (e.g., 5% Contrad 70) for rigorous cleaning of the instrument's sample cell and syringe to prevent contamination and maintain baseline stability. |

| Degassing Station | A device that applies vacuum and gentle stirring/agitation to remove dissolved gases from solutions, critical for preventing noise and bubbles during the ITC experiment. |

| Analysis Software | Vendor-specific (e.g., MicroCal PEAQ-ITC, Malvern MicroCal) or third-party (e.g., NITPIC, SEDPHAT) for integrating thermogram peaks and fitting binding models. |

The Euler Reciprocity Condition and the Concept of Exactness

Within the broader thesis on the derivation and meaning of Maxwell relations, the Euler reciprocity condition emerges as the foundational mathematical criterion for exact differentials. In thermodynamics, the identification of state functions—such as internal energy ( U ), entropy ( S ), and Gibbs free energy ( G )—relies on this condition. For a differential form ( dF = M(x,y)dx + N(x,y)dy ) to be exact (path-independent), the Euler reciprocity condition must hold: ( \left(\frac{\partial M}{\partial y}\right)x = \left(\frac{\partial N}{\partial x}\right)y ). This condition ensures ( F ) is a state function, enabling the derivation of Maxwell's relations, which are critical for connecting measurable thermodynamic quantities in physical chemistry and drug development (e.g., solubility, partition coefficients, stability).

Theoretical Foundation

The calculus of thermodynamic potentials is built on the concept of exact differentials. For a function ( F(x, y) ), the total differential is: [ dF = \left(\frac{\partial F}{\partial x}\right)y dx + \left(\frac{\partial F}{\partial y}\right)x dy. ] If given ( dF = M dx + N dy ), exactness requires the equality of cross-partial derivatives: [ \frac{\partial^2 F}{\partial y \partial x} = \frac{\partial^2 F}{\partial x \partial y} \quad \Rightarrow \quad \left(\frac{\partial M}{\partial y}\right)x = \left(\frac{\partial N}{\partial x}\right)y. ] This is the Euler reciprocity condition. Violation implies ( dF ) is inexact, representing a path-dependent quantity like heat or work. The condition is directly applied to the fundamental thermodynamic relation ( dU = T dS - P dV ), yielding the first Maxwell relation: ( \left(\frac{\partial T}{\partial V}\right)S = -\left(\frac{\partial P}{\partial S}\right)V ).

Experimental Validation in Thermodynamic Systems

Protocol: Validating Exactness for a Model Substance

- Objective: To experimentally verify the Euler reciprocity condition for the enthalpy ( H(S, P) ) of a pure gas.

- System: Argon gas in a controlled calorimeter with adjustable pressure and volume.

- Procedure:

- Measure heat capacity at constant pressure ( CP ) over a temperature range (100-300 K) at a fixed pressure ( P0 ).

- Perform a Joule-Thomson expansion experiment to determine the Joule-Thomson coefficient ( \mu{JT} = \left(\frac{\partial T}{\partial P}\right)H ).

- From ( \mu{JT} ) and ( CP ), calculate the derivative ( \left(\frac{\partial H}{\partial P}\right)T = -CP \cdot \mu{JT} ).

- Independently, measure the thermal expansion coefficient ( \alpha = \frac{1}{V}\left(\frac{\partial V}{\partial T}\right)P ) and use the relation ( \left(\frac{\partial H}{\partial P}\right)T = V - T\left(\frac{\partial V}{\partial T}\right)P = V(1 - T\alpha) ).

- Validation: Compare the values of ( \left(\frac{\partial H}{\partial P}\right)T ) obtained from steps 3 and 4. Agreement within experimental uncertainty confirms the condition ( \frac{\partial}{\partial T}\left(\frac{\partial H}{\partial P}\right)T = \frac{\partial}{\partial P}\left(C_P\right) ), a specific instance of Euler reciprocity.

Data Presentation

Table 1: Experimental Data for Argon Gas at 1 atm

| Temperature (K) | ( C_P ) (J/mol·K) [Measured] | ( \mu_{JT} ) (K/atm) [Measured] | ( \left(\frac{\partial H}{\partial P}\right)T ) (J/mol·atm) [from ( CP, \mu_{JT} )] | ( \alpha ) (K⁻¹) [Measured] | ( \left(\frac{\partial H}{\partial P}\right)_T ) (J/mol·atm) [from ( V, \alpha )] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 120 | 21.05 | 0.431 | -9.07 | 0.00831 | -9.12 |

| 180 | 20.79 | 0.229 | -4.76 | 0.00555 | -4.81 |

| 240 | 20.88 | 0.128 | -2.67 | 0.00416 | -2.65 |

| 300 | 20.99 | 0.071 | -1.49 | 0.00333 | -1.51 |

Table 2: Key Thermodynamic Maxwell Relations Derived from Exact Differentials

| Thermodynamic Potential | Exact Differential | Applied Euler Condition | Resulting Maxwell Relation | Application in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy (U) | ( dU = TdS - PdV ) | ( \left(\frac{\partial T}{\partial V}\right)S = -\left(\frac{\partial P}{\partial S}\right)V ) | ( \left(\frac{\partial T}{\partial V}\right)S = -\left(\frac{\partial P}{\partial S}\right)V ) | Rare; used in adiabatic processes. |

| Enthalpy (H) | ( dH = TdS + VdP ) | ( \left(\frac{\partial T}{\partial P}\right)S = \left(\frac{\partial V}{\partial S}\right)P ) | ( \left(\frac{\partial T}{\partial P}\right)S = \left(\frac{\partial V}{\partial S}\right)P ) | Relates temperature change with pressure to entropy-volume coupling. |

| Helmholtz Free Energy (F) | ( dF = -SdT - PdV ) | ( \left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial V}\right)T = \left(\frac{\partial P}{\partial T}\right)V ) | ( \left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial V}\right)T = \left(\frac{\partial P}{\partial T}\right)V ) | Critical for relating pressure-temperature coefficients to entropy of expansion (protein unfolding). |

| Gibbs Free Energy (G) | ( dG = -SdT + VdP ) | ( -\left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial P}\right)T = \left(\frac{\partial V}{\partial T}\right)P ) | ( \left(\frac{\partial S}{\partial P}\right)T = -\left(\frac{\partial V}{\partial T}\right)P ) | Most significant. Predicts how solubility, chemical equilibrium (binding constants), and phase stability change with T and P. |

Visualization

Title: Logical Flow from Function to Exactness

Title: Derivation of a Maxwell Relation from Exactness

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials for Thermodynamic Validation

| Item | Function/Description |

|---|---|

| High-Precision Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measures heat capacity ( CP ) and phase transition enthalpies with high accuracy, essential for obtaining ( (\partial S/\partial T)P ). |

| Pressure-Tuning Cell with Spectroscopic Windows | Allows measurement of volume ( V ), thermal expansion coefficient ( \alpha ), and compressibility under varying P/T for derivatives like ( (\partial V/\partial T)_P ). |

| Joule-Thomson Inversion Apparatus | Directly measures the Joule-Thomson coefficient ( \mu_{JT} ), providing data to cross-verify Euler-derived relationships. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimeter (ITC) | The primary tool in drug development for measuring binding Gibbs free energy ( \Delta G ), enthalpy ( \Delta H ), and entropy ( \Delta S ), all interconnected by Maxwell relations. |

| Computational Chemistry Software (e.g., Gaussian, GROMACS) | Performs molecular dynamics and ab initio calculations to compute thermodynamic derivatives (e.g., ( (\partial^2 G/\partial T \partial P) )) for complex molecular systems. |

| Certified Reference Materials (e.g., pure water, argon) | Provide benchmark data for calibration and validation of experimental setups measuring thermodynamic properties. |

This whitepaper is situated within a broader research thesis investigating the systematic derivation and profound physical meaning of Maxwell relations in thermodynamics. These relations, derived from the symmetry of second derivatives of thermodynamic potentials, are not merely mathematical curiosities but fundamental constraints that govern the behavior of physical and chemical systems. In drug development, understanding these relationships is critical for predicting solubility, membrane permeability, protein-ligand binding energetics, and stability of pharmaceutical formulations. This guide deconstructs the logical pathway from defining a thermodynamic potential to establishing the exact differential and, finally, extracting the Maxwell relations, with a focus on visualization and application.

Foundational Thermodynamic Potentials and Their Differentials

The journey begins with the definition of key thermodynamic potentials, each natural to specific experimental conditions (e.g., constant N,V,T; N,P,S). Their exact differentials provide the bridge to partial derivative identities.

Table 1: Core Thermodynamic Potentials and Their Exact Differentials

| Potential & Symbol | Natural Variables | Exact Differential | Primary Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy (U) | Entropy (S), Volume (V), Particle Number (N) | dU = TdS – PdV + μdN | Fundamental energy for isolated systems. |

| Helmholtz Free Energy (F) | Temperature (T), Volume (V), N | dF = –SdT – PdV + μdN | Processes at constant T and V (e.g., in-silico molecular simulations). |

| Enthalpy (H) | Entropy (S), Pressure (P), N | dH = TdS + VdP + μdN | Heat changes at constant pressure (e.g., calorimetry). |

| Gibbs Free Energy (G) | Temperature (T), Pressure (P), N | dG = –SdT + VdP + μdN | Phase equilibria, chemical reactions, drug binding (constant T, P). |

| Grand Potential (Ω) | T, V, Chemical Potential (μ) | dΩ = –SdT – PdV – Ndμ | Open systems at constant μ. |

The Logical Pathway to Maxwell Relations

For any exact differential dz = Mdx + Ndy, the equality of mixed partials holds: (∂M/∂y)x = (∂N/∂x)y. Applying this theorem to the differentials in Table 1 yields the Maxwell relations.

Diagram 1: Logical Derivation of a Maxwell Relation

Experimental Protocols for Measuring Maxwell Relation-Dependent Properties

Protocol: Determining (∂V/∂T)P for a Protein Solution (Related to -(∂S/∂P)T)

Objective: Measure the thermal expansion coefficient, α = (1/V)(∂V/∂T)_P, of a protein in buffer. This relates via a Maxwell relation to the change in entropy with pressure.

- Sample Preparation: Prepare a degassed, concentrated solution of the target protein (e.g., 5-10 mg/mL in relevant buffer). Load into a high-precision vibrating tube densimeter cell.

- Density Measurement: Set the instrument to perform a temperature ramp (e.g., 10°C to 40°C) at a constant pressure (atmospheric). Record the solution density (ρ) at 0.1°C intervals.

- Data Analysis: Calculate the specific volume, v = 1/ρ. Fit v(T) to a polynomial. Differentiate to obtain (∂v/∂T)_P. The partial molar volume and its temperature derivative can be extracted via appropriate thermodynamic mixing relations.

Protocol: Calorimetric Measurement of (∂S/∂T)P (Heat Capacity) and Link to (∂V/∂P)T

Objective: Measure the constant-pressure heat capacity, CP = T(∂S/∂T)P. Via the Maxwell relation (∂S/∂P)T = -(∂V/∂T)P, the temperature dependence of C_P relates to the pressure dependence of α.

- Instrumentation: Use a differential scanning calorimeter (DSC) with high-pressure capability.

- Isothermal Compression Experiment: Equilibrate the protein/buffer sample and reference at a fixed temperature (T1). Perform a slow pressure scan while measuring the differential heat flow.

- Analysis: The measured heat flow is related to T*(∂S/∂P)T. Integrate data to obtain ΔS(P) at T1. Repeat at temperature T2. The difference [ΔS(P)T2 - ΔS(P)T1] / (T2-T1) provides an experimental cross-check on (∂CP/∂P)T, which is related to -(∂²V/∂T²)P.

Key Maxwell Relations and Quantitative Data

Table 2: Key Maxwell Relations Derived from Common Potentials

| Deriving Potential | Exact Differential | Resulting Maxwell Relation | Practical Implication in Drug Development |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy (U) | dU = TdS – PdV | (∂T/∂V)S = –(∂P/∂S)V | Relevant for adiabatic processes. |

| Helmholtz (F) | dF = –SdT – PdV | (∂S/∂V)T = (∂P/∂T)V | Predicts entropy change upon expansion from PVT data. |

| Enthalpy (H) | dH = TdS + VdP | (∂T/∂P)S = (∂V/∂S)P | Governs temperature change in adiabatic compression. |

| Gibbs (G) | dG = –SdT + VdP | (∂S/∂P)T = –(∂V/∂T)P | Crucial: Predicts how entropy (disorder) changes with pressure from easily measured thermal expansion. |

Table 3: Exemplar Data for Pharmaceutical Solvent (Water) at 25°C, 1 bar Data validates the Maxwell relation (∂S/∂P)_T = –(∂V/∂T)_P.

| Property | Symbol | Value | Method / Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Thermal Expansion Coeff. | α = (1/V)(∂V/∂T)_P | 257.1 x 10⁻⁶ K⁻¹ | Densitometry |

| Calculated (∂V/∂T)_P | α * V_m | +4.63 x 10⁻³ cm³ mol⁻¹ K⁻¹ | Derived |

| Isothermal Compressibility | κT = -(1/V)(∂V/∂P)T | 45.24 x 10⁻⁶ bar⁻¹ | Ultrasound Speed |

| Entropy Derivative (Calc.) | (∂S/∂P)T = -α Vm | -4.63 x 10⁻³ J mol⁻¹ K⁻¹ bar⁻¹ | Via Maxwell from left |

| Entropy Derivative (Lit.) | (∂S/∂P)_T | ~ -4.6 x 10⁻³ J mol⁻¹ K⁻¹ bar⁻¹ | Thermodynamic Tables |

Visualizing the Network of Relationships

The Maxwell relations create a tightly coupled network of thermodynamic properties.

Diagram 2: Network of Related Thermodynamic Properties

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions & Essential Materials

Table 4: Essential Materials for Thermodynamic Property Measurement

| Item / Reagent Solution | Function in Experiment | Critical Specification / Note |

|---|---|---|

| High-Precision Densitimeter | Measures solution density (ρ) as f(T,P) to derive V, α, κ_T. | Requires microdegree temperature stability and degassing module. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) | Measures heat capacity (C_P) and phase transition enthalpies/entropies. | High-pressure cell extends utility for Maxwell relation studies. |

| Stable Protein Buffer System | Provides a constant, non-interacting environment for protein studies. | Must be matched in sample and reference cells; low ionic strength preferred for densimetry. |

| Degassed, Ultrapure Water | Primary calibrant and reference fluid for all measurements. | Resistivity >18 MΩ·cm, degassed to prevent bubble formation in cells. |

| Reference Standard (e.g., Toluene) | Validates instrument calibration for thermal expansion (α) measurements. | Certified α value traceable to national standards. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimeter (ITC) | Directly measures ΔG, ΔH, ΔS of binding (a key application of Gibbs free energy). | Not for partial derivatives directly, but for validating thermodynamic models. |

Deriving and Applying Maxwell Relations in Drug Discovery and Biophysics

This whitepaper serves as a foundational component of a broader thesis on the derivation and physical meaning of Maxwell relations in thermodynamics. These relations are not mere mathematical curiosities but are essential tools for connecting measurable quantities (like heat capacities and coefficients of expansion) to non-measurable ones (like entropy changes). In fields ranging from materials science to drug development, they enable the prediction of a system's response under various constraints, crucial for understanding protein folding, ligand binding, and polymer behavior.

Foundational Differential: The First Law Combined

The starting point is the fundamental thermodynamic relation for the internal energy ( U ) of a closed, simple compressible system: [ dU = TdS - PdV ] This equation synthesizes the first law of thermodynamics (conservation of energy) with the second law (definition of entropy, ( dS = \delta q_{rev}/T )). It states that changes in internal energy are driven by thermal (( TdS )) and mechanical (( -PdV )) work in a reversible process.

Step-by-Step Derivation of the First Maxwell Relations

Recognizing ( U ) as a function of entropy ( S ) and volume ( V ), ( U(S, V) ), its total differential is: [ dU = \left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial S} \right)V dS + \left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)S dV ] A direct term-by-term comparison with ( dU = TdS - PdV ) yields the first set of natural derivative definitions: [ \left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial S} \right)V = T \quad \text{and} \quad \left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right)S = -P ]

Applying the Criterion for Exact Differentials

The differential ( dU ) is exact (a state function). A necessary and sufficient condition for exactness is the equality of the cross-partial derivatives (Schwarz's theorem). Applying this to the coefficients of ( dS ) and ( dV ): [ \frac{\partial}{\partial V} \left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial S} \right) = \frac{\partial}{\partial S} \left( \frac{\partial U}{\partial V} \right) ] Substituting the identified coefficients (( T ) and ( -P )): [ \left( \frac{\partial T}{\partial V} \right)S = -\left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial S} \right)V ] This is the first Maxwell relation. It connects the isentropic (adiabatic) variation of temperature with volume to the isochoric variation of pressure with entropy.

Extending to Other Thermodynamic Potentials

The internal energy ( U(S,V) ) is natural for isolated systems. To handle real-world experimental conditions (constant T, P), other potentials are defined via Legendre transforms. Each yields a fundamental relation and corresponding Maxwell relations.

Enthalpy (( H )): ( H = U + PV ). Differentiating: ( dH = dU + PdV + VdP ). Substituting ( dU ): [ dH = TdS + VdP ] Following the same procedure (treating ( H(S, P) )) yields: [ \left( \frac{\partial T}{\partial P} \right)S = \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial S} \right)P ]

Helmholtz Free Energy (( F )): ( F = U - TS ). Differentiating: ( dF = dU - TdS - SdT ). [ dF = -SdT - PdV ] From ( F(T, V) ), we derive: [ \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)T = \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial T} \right)V ] This is one of the most practically useful Maxwell relations, linking isothermal entropy change with volume to the easily measured thermal pressure coefficient.

Gibbs Free Energy (( G )): ( G = H - TS = U + PV - TS ). Differentiating: ( dG = dH - TdS - SdT ). [ dG = -SdT + VdP ] From ( G(T, P) ), we derive: [ -\left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial P} \right)T = \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T} \right)P ] This connects the isothermal pressure dependence of entropy to the thermal expansion coefficient.

Table 1: Fundamental Thermodynamic Differentials and First Maxwell Relations

| Thermodynamic Potential | Natural Variables | Fundamental Relation | Derived Maxwell Relation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy (U) | S, V | ( dU = TdS - PdV ) | ( \left( \frac{\partial T}{\partial V} \right)S = -\left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial S} \right)V ) |

| Enthalpy (H) | S, P | ( dH = TdS + VdP ) | ( \left( \frac{\partial T}{\partial P} \right)S = \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial S} \right)P ) |

| Helmholtz Free Energy (F) | T, V | ( dF = -SdT - PdV ) | ( \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)T = \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial T} \right)V ) |

| Gibbs Free Energy (G) | T, P | ( dG = -SdT + VdP ) | ( -\left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial P} \right)T = \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T} \right)P ) |

Experimental Protocol: Measuring (∂P/∂T)V to Find (∂S/∂V)T

This protocol details an experiment to verify a Maxwell relation, specifically for a pure gas.

Objective: Determine the change in entropy with volume at constant temperature, ( \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)T ), indirectly by measuring the change in pressure with temperature at constant volume, ( \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial T} \right)V ), using the Maxwell relation from ( dF ).

Methodology:

- Apparatus: A high-precision constant-volume cell (pressure bomb) equipped with a calibrated pressure transducer and a thermocouple/RTD. The cell is submerged in a programmable thermal bath.

- System Preparation: Evacuate the cell and then fill it with a known, fixed amount of pure research gas (e.g., Argon). Ensure the system reaches thermal equilibrium at a starting temperature ( T_1 ).

- Data Acquisition:

- Record the initial equilibrium pressure ( P1 ) at ( T1 ).

- Incrementally increase the bath temperature in small steps (e.g., 2-5 K).

- At each new temperature ( Ti ), allow the system to re-equilibrate fully, then record the corresponding pressure ( Pi ). Volume remains constant.

- Data Analysis:

- Plot ( P ) vs. ( T ) for the constant-volume process.

- Perform a linear regression (or fit an appropriate equation of state, e.g., Virial) on the ( P(T) ) data.

- The slope of this curve at any given temperature is ( \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial T} \right)V ).

- By Maxwell relation, this slope equals ( \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)T ) for the gas at that temperature and molar volume.

Logical Derivation Pathway Diagram

Title: Logical Flow from dU to Maxwell Relations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Thermodynamic Experiments

| Item | Function in Experimental Context |

|---|---|

| High-Purity Calorimetry Gases (e.g., N₂, Ar) | Inert, well-characterized working fluids for pressure-volume-temperature (PVT) experiments to determine equations of state and partial derivatives. |

| Reference Buffer Solutions (e.g., PBS, Tris-HCl) | Provide a constant ionic strength and pH environment for thermodynamic studies of biomolecular interactions (e.g., by Isothermal Titration Calorimetry, ITC). |

| Ligand & Protein Stocks (Lyophilized/Purified) | The molecular actors in drug development studies; their binding thermodynamics (ΔG, ΔH, ΔS) are derived from data using Maxwell relations indirectly. |

| Thermal Bath Fluid (e.g., Silicone Oil) | High-stability fluid for precise temperature control of reaction cells and pressure vessels over extended periods. |

| Calibrated Pressure Transducer | Precisely measures pressure changes in constant-volume experiments to determine derivatives like (∂P/∂T)v. |

| Differential Scanning Calorimeter (DSC) Cell | Measures heat capacity changes directly, a key quantity linked to second derivatives of thermodynamic potentials. |

Systematic Derivation Strategy for Enthalpy, Helmholtz, and Gibbs Potentials

This whitepaper presents a systematic derivation strategy for the three principal thermodynamic potentials—Enthalpy (H), Helmholtz Free Energy (A), and Gibbs Free Energy (G). This work is framed within a broader research thesis on the derivation and physical meaning of Maxwell relations, which are the direct mathematical consequence of the exactness (or integrability conditions) of these potentials. For researchers in pharmaceutical development, mastery of these potentials and their interrelations is critical for understanding drug solubility, protein folding stability, membrane permeability, and reaction spontaneity under constant temperature and pressure conditions—the typical experimental milieu.

The central thesis posits that a unified, logical derivation from the First and Second Laws of Thermodynamics, followed by Legendre transformations, not only clarifies the individual meaning of each potential but also makes the emergence of the Maxwell relations inevitable and interpretable.

Foundational Laws and the Internal Energy

All derivations originate from the First Law (energy conservation) and the Second Law (defining entropy) for a closed, simple compressible system: [ dU = \delta q + \delta w ] For a reversible process, this becomes: [ dU = TdS - PdV ] where (U(S, V)) is the internal energy, a function of its natural variables (S) and (V). This is the fundamental thermodynamic relation from which all else flows.

Table 1: Core Thermodynamic Differentials and Natural Variables

| Thermodynamic Potential | Symbol & Definition | Differential Form | Natural Variables |

|---|---|---|---|

| Internal Energy | (U) | (dU = TdS - PdV) | (S, V) |

| Enthalpy | (H = U + PV) | (dH = TdS + VdP) | (S, P) |

| Helmholtz Free Energy | (A = U - TS) | (dA = -SdT - PdV) | (T, V) |

| Gibbs Free Energy | (G = H - TS = U + PV - TS) | (dG = -SdT + VdP) | (T, P) |

Systematic Derivation via Legendre Transformations

The transformation from (U(S,V)) to other potentials is a systematic process of changing the independent variables via Legendre transforms.

Enthalpy (H) Derivation

Objective: Change the variable (V) to its conjugate (-P) while retaining (S). Transform: (H = U + PV) Derivation: [ dH = d(U + PV) = dU + PdV + VdP ] Substitute (dU = TdS - PdV): [ dH = (TdS - PdV) + PdV + VdP = TdS + VdP ] Thus, (H = H(S, P)). Enthalpy is the preferred potential for constant-pressure processes (e.g., chemical reactions in open vessels).

Helmholtz Free Energy (A) Derivation

Objective: Change the variable (S) to its conjugate (T) while retaining (V). Transform: (A = U - TS) Derivation: [ dA = d(U - TS) = dU - TdS - SdT ] Substitute (dU = TdS - PdV): [ dA = (TdS - PdV) - TdS - SdT = -SdT - PdV ] Thus, (A = A(T, V)). Helmholtz energy is central to statistical mechanics and processes at constant temperature and volume (e.g., in a rigid, isothermal reactor).

Gibbs Free Energy (G) Derivation

Objective: Change both variables: (S \rightarrow T) and (V \rightarrow P). Transform: (G = U + PV - TS = H - TS) Derivation: [ dG = d(H - TS) = dH - TdS - SdT ] Substitute (dH = TdS + VdP): [ dG = (TdS + VdP) - TdS - SdT = -SdT + VdP ] Thus, (G = G(T, P)). Gibbs energy is the paramount potential for chemistry and biology, predicting spontaneity at constant temperature and pressure.

Emergence of Maxwell Relations

Each potential's exact differential ((dZ = Mdx + Ndy)) requires that the mixed partial derivatives are equal: ((\partial M/\partial y)x = (\partial N/\partial x)y). This yields the Maxwell relations.

Table 2: Maxwell Relations from Each Thermodynamic Potential

| Potential | Differential | Maxwell Relation | Application Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| U(S,V) | (dU=TdS-PdV) | ((\partial T/\partial V)S = -(\partial P/\partial S)V) | Adiabatic expansion |

| H(S,P) | (dH=TdS+VdP) | ((\partial T/\partial P)S = (\partial V/\partial S)P) | Joule-Thomson coefficient |

| A(T,V) | (dA=-SdT-PdV) | ((\partial S/\partial V)T = (\partial P/\partial T)V) | Thermal pressure coefficient |

| G(T,P) | (dG=-SdT+VdP) | -((\partial S/\partial P)T = (\partial V/\partial T)P) | Crucial for drug solubility & phase equilibria |

The final relation from (G), (-(\partial S/\partial P)T = (\partial V/\partial T)P), links thermal expansion to entropy change with pressure, directly applicable to understanding how temperature affects solubility and partition coefficients.

Experimental Protocols for Potential Determination

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for ΔG, ΔH, and ΔS

Purpose: Direct measurement of binding thermodynamics (ΔG, ΔH, ΔS) in drug-target interactions. Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Purify protein (target) and ligand (drug candidate) in identical buffer (pH, ionic strength). Degas to prevent bubbles.

- Instrument Setup: Load protein solution (typically 0.1-0.5 mL) into the sample cell. Fill reference cell with buffer. Load ligand solution into the syringe.

- Titration Program: Set constant temperature (25-37°C). Program a series of injections (e.g., 19 injections of 2 µL each) with spacing (e.g., 180s) for equilibrium.

- Data Collection: The instrument measures the heat flow (µJ/sec) required to maintain zero temperature difference between sample and reference cells after each injection.

- Data Analysis: Integrate heat peaks to get total heat per injection. Fit the binding isotherm (heat vs. molar ratio) to a model (e.g., one-site binding) to derive:

- (Kd) (dissociation constant) → (\Delta G = -RT \ln(Ka)) where (Ka = 1/Kd)

- (\Delta H) (binding enthalpy) directly from the fitted curve.

- (\Delta S) calculated via (\Delta G = \Delta H - T\Delta S).

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC) for Protein Stability (ΔH of unfolding)

Purpose: Determine the Gibbs and Helmholtz energy landscape of protein folding/unfolding. Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Prepare protein and reference (buffer) solutions at identical concentrations (0.1-1 mg/mL). Degas.

- Scanning Program: Set a constant scan rate (e.g., 1°C/min) over a temperature range spanning the unfolding transition (e.g., 20°C to 100°C).

- Data Collection: Measure the difference in heat input ((C_p)) between sample and reference cells as a function of temperature.

- Data Analysis: Identify the melting temperature (Tm) (peak of the heat capacity curve). Integrate the excess heat capacity curve to obtain the calorimetric enthalpy of unfolding, (\Delta H{cal}). The van't Hoff enthalpy, (\Delta H{vH}), is derived from the shape of the transition curve. Comparison of (\Delta H{cal}) and (\Delta H_{vH}) provides insight into the cooperativity of the unfolding process, related to the second derivatives of (G) or (A).

Visualization of Derivative Relationships and Pathways

Title: Systematic Derivation of Thermodynamic Potentials and Maxwell Relations

Title: Decision Workflow for Selecting the Appropriate Thermodynamic Potential

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Thermodynamic Measurements

| Item | Function/Brief Explanation | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) Cell Cleaning Solution | Aqueous-based, non-ionic detergent solution. Removes tightly bound biomolecules from the sample cell without damaging the gold coating. | Post-experiment cleaning of ITC instrument after protein-ligand binding studies. |

| DSC Reference Buffer | Precisely matched buffer (same pH, salts, additives) used in the reference cell. Essential for obtaining a flat, stable baseline by compensating for the heat capacity of the solvent. | Measuring protein unfolding thermodynamics via Differential Scanning Calorimetry. |

| High-Purity Ligand Compounds | >95-99% pure drug candidate molecules, solubilized in the exact same buffer as the target protein. Buffer mismatch is a primary source of error in ITC. | Preparing the syringe solution for an ITC binding assay. |

| Chemically-Defined Stabilization Buffers | Buffers with agents like TCEP (reducing agent), EDTA (chelator), or polysorbates. Minimize confounding heat signals from oxidation, metal binding, or aggregation. | Maintaining protein target stability during lengthy thermodynamic assays. |

| Calorimetry Calibration Standards | Chemicals with precisely known enthalpies of reaction or dilution (e.g., Tris-HCl for pH titration, propanol for DSC). Validates instrument performance and signal response. | Quarterly calibration of ITC and DSC instruments to ensure data accuracy. |

| High-Pressure Reaction Vessels | Chemically inert vessels (e.g., Hastelloy) capable of withstanding high pressures for measuring ΔV of reaction via partial molar volume studies. | Experimental determination of (∂ΔG/∂P)_T = ΔV for solvation/reaction studies. |

Within the broader thesis on the derivation and physical meaning of Maxwell relations, the development of robust mnemonic tools is not merely a pedagogical convenience but a research accelerator. Maxwell's relations, the set of equations derived from the equality of mixed partials of thermodynamic potentials, are foundational for deriving relationships between measurable quantities (e.g., heat capacities, compressibilities) and for manipulating expressions in statistical mechanics and materials design. This whitepaper details the Thermodynamic Square (or "Born Square") mnemonic and the more rigorous, generalized Jacobian method, providing researchers and drug development professionals with efficient protocols for recall, derivation, and application.

The Thermodynamic Square Mnemonic: Protocol and Diagram

The Thermodynamic Square provides a visual algorithm for generating the four primary Maxwell relations.

Experimental/Application Protocol:

- Draw the Square: Inscribe a square. At each vertex, clockwise from the top, place the variables: V (Volume), T (Temperature), P (Pressure), S (Entropy).

- Label the Sides: On each side, place the corresponding natural variable of the potentials: The top side (between V and T) gets S; the right side (T-P) gets V; the bottom (P-S) gets T; the left (S-V) gets P.

- Derivation Rule:

- Select a potential from a corner (e.g., F = Helmholtz Free Energy at the V-T corner). Its natural variables are the two adjacent sides (S and V for F? Correction: For F(V,T), the natural variables are the adjacent corners: V and T. The sides represent the other variables).

- A Maxwell relation is obtained from the diagonal of the square. The derivative of the side variable at one end with respect to the corner variable at the other, holding the opposite side variable constant, equals a similar derivative with signs determined by the direction.

- Mnemonic Rule of Thumb: "The partial derivative of the variable at one corner with respect to the variable at an adjacent corner, while holding the variable on the far side constant, is related to the derivative of the variable on the other adjacent corner." A more precise algorithmic protocol is below.

A more reliable algorithmic protocol uses the square's geometry:

- Identify the two variables for your partial derivative (e.g., you want

(∂S/∂V)_T). - Locate these two variables on the square. They will be connected by a diagonal or a side.

- If connected by a side: The derivative is simply the other variable on the opposite side, with a sign determined by the direction (clockwise sequence gives a positive sign, counterclockwise gives negative). This is less common.

- If connected by a diagonal (the Maxwell relation case):

a. The derivative equals the derivative of the other two variables.

b. The constant-held variable is the one opposite your starting variable.

c. The sign is positive if the two variables in the derivative are in clockwise order (e.g., from T to P is clockwise, so

(∂T/∂P)_Sis positive), and negative if in counterclockwise order.

Logical Relationship Diagram:

Diagram Title: Thermodynamic Square for Maxwell Relations

The Jacobian Method: A Rigorous Computational Protocol

The Jacobian method provides a systematic, algebraic framework for manipulating partial derivatives in thermodynamics, extending beyond the four common potentials.

Theoretical Foundation: For a transformation from variables (x, y) to (u, v), the Jacobian is defined as:

∂(u,v)/∂(x,y) = | ∂u/∂x ∂u/∂y; ∂v/∂x ∂v/∂y |

Key Operational Protocols:

- Basic Identity:

(∂u/∂x)_y = ∂(u,y)/∂(x,y) - Inverse Rule:

∂(u,v)/∂(x,y) = 1 / [∂(x,y)/∂(u,v)] - Chain Rule:

∂(u,v)/∂(x,y) = [∂(u,v)/∂(w,z)] * [∂(w,z)/∂(x,y)] - Cyclic Rule (Maxwell Relation Generator):

∂(x,y)/∂(u,v) + ∂(y,u)/∂(u,v) + ∂(u,x)/∂(u,v) = 0, which simplifies to(∂x/∂u)_v (∂y/∂x)_u (∂u/∂y)_x = -1.

Experimental Derivation Protocol for a General Maxwell Relation:

- State the Target: Express the desired derivative in Jacobian form. E.g.,

(∂S/∂V)_T = ∂(S,T)/∂(V,T). - Transform Variables: Use Jacobian properties to introduce the conjugate variables of a known potential. For Gibbs free energy G(T,P), the natural variables are T and P. We know

dG = -S dT + V dP, implyingS = -(∂G/∂T)_PandV = (∂G/∂P)_T. - Perform Manipulation: Since S and V are both first derivatives of G, their Jacobians with respect to (P,T) yield second derivatives.

- Evaluate using equality of mixed partials:

∂(S,T)/∂(P,T) = (∂S/∂P)_T = -(∂²G/∂T∂P). Similarly,∂(V,T)/∂(P,T) = (∂V/∂P)_T = (∂²G/∂P²)_T. The more standard Maxwell from G is(∂S/∂P)_T = -(∂V/∂T)_P. - Arrive at Result: Through this systematic manipulation, one can derive

(∂S/∂V)_T = (∂P/∂T)_V, which is a Maxwell relation from the Helmholtz free energy.

Diagram of Jacobian Manipulation Workflow:

Diagram Title: Jacobian Method Derivation Workflow

Comparative Analysis & Data Presentation

The following tables summarize the key characteristics, advantages, and outputs of both methods.

Table 1: Method Comparison for Maxwell Relation Derivation

| Feature | Thermodynamic Square | Jacobian Method |

|---|---|---|

| Basis | Geometric mnemonic | Rigorous mathematical formalism |

| Scope | Four primary relations (from U, H, F, G) | Unlimited; any variable transformation |

| Ease of Recall | Very high for core set | Requires memorization of rules |

| Risk of Error | Moderate (sign errors common) | Low if rules applied systematically |

| Best For | Quick recall in research settings | Deriving novel, non-standard relations |

| Key Output | (∂T/∂V)_S = -(∂P/∂S)_V, (∂S/∂P)_T = -(∂V/∂T)_P, etc. |

General form: ∂(X,Y)/∂(U,V) = ... |

Table 2: Derived Quantities Accessible via These Methods

| Thermodynamic Quantity | Defining Expression | Relevant Maxwell Relation for Simplification |

|---|---|---|

| Isothermal Compressibility (κ_T) | κ_T = -1/V (∂V/∂P)_T |

May use (∂V/∂P)_T = - (∂S/∂T)_P / (∂S/∂P)_T |

| Adiabatic Compressibility (κ_S) | κ_S = -1/V (∂V/∂P)_S |

Related via (∂P/∂V)_S from square/Jacobian |

| Heat Capacity at Const. Vol (C_V) | C_V = T (∂S/∂T)_V |

(∂S/∂T)_V = (∂²F/∂T²)_V |

| Heat Capacity at Const. Press (C_P) | C_P = T (∂S/∂T)_P |

(∂S/∂T)_P = -(∂²G/∂T²)_P |

| Coeff. of Thermal Expansion (α) | α = 1/V (∂V/∂T)_P |

Directly from Maxwell: (∂V/∂T)_P = -(∂S/∂P)_T |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Analytical Tools for Thermodynamic Research

| Item/Concept | Function in Research | |

|---|---|---|

| Fundamental Relation | dU = T dS - P dV + Σ μ_i dN_i |

The axiomatic starting point for all derivations. |

| Legendre Transform | L[f(x)] = f - x (∂f/∂x) |

Mathematical operation to change independent variables (e.g., U(S,V) → F(T,V)=U-TS). |

| Schwarz's Theorem | ∂²Φ/∂x∂y = ∂²Φ/∂y∂x |

The mathematical cornerstone guaranteeing the validity of Maxwell relations. |

| Equation of State (EOS) | e.g., P = P(V,T,N) |

Empirical or theoretical model (e.g., van der Waals, PR-EOS) required to evaluate derived derivatives numerically. |

| Computational Algebra | Software like Mathematica, SymPy | Essential for implementing Jacobian manipulations symbolically and avoiding algebraic errors in complex systems. |

| Calorimetry & PVT Data | Experimental datasets for Cp, α, κ_T | Required to validate derived relationships and populate models for drug solubility, protein folding, etc. |

Within the broader thesis on Maxwell relations derivation and meaning, this whitepaper addresses a fundamental challenge in thermodynamics: the direct measurement of entropy (S), a state function quantifying disorder, is impossible. Entropy changes (dS) are immeasurable, yet they govern spontaneity and stability in chemical and biological systems, including drug-target interactions. The core application demonstrated here is the use of Maxwell relations—derived from the exact differentials of thermodynamic potentials—to connect these immeasurable entropy changes to directly measurable properties: pressure (P), volume (V), and temperature (T). This bridge is critical for researchers and drug development professionals who require quantitative thermodynamic profiling of molecular processes.

Theoretical Foundation: Maxwell Relations as the Bridge

Maxwell relations are a direct consequence of the symmetry of second derivatives of state functions (U, H, A, G) and the exactness of their differentials. For a system with constant composition, they provide equivalent expressions for a partial derivative that may be difficult to measure.

The most pertinent relation for connecting entropy to PVT data is derived from the Helmholtz free energy (A = U - TS): [ dA = -SdT - PdV ] Applying the equality of mixed partial derivatives: [ \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)T = \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial T} \right)V ]

This Maxwell relation is transformative: The left side, ((\partial S/\partial V)T), represents the change in entropy with volume at constant temperature—an "immeasurable" entropy-based quantity. The right side, ((\partial P/\partial T)V), is the isochoric (constant-volume) thermal pressure coefficient—a fully measurable quantity using PVT data.

Quantifying Entropy Changes from Experimental PVT Data

The core application proceeds by measuring ((\partial P/\partial T)_V) and integrating to find finite entropy changes.

Key Measurable Quantities and Data

The following table summarizes the primary measurable coefficients derived from PVT data that link to entropy via Maxwell relations.

Table 1: Key Thermodynamic Coefficients Linking PVT Data to Entropy

| Coefficient | Definition | Maxwell Relation Link | Typical Measurement Method | Representative Value (Liquid Water, 25°C, 1 atm) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Isochoric Thermal Pressure Coefficient (β_V) | ( \betaV = \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial T} \right)V ) | ( \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial V} \right)T = \betaV ) | High-pressure dilatometry / Piezometer | ~ 0.00046 MPa/K |

| Isothermal Compressibility (κ_T) | ( \kappaT = -\frac{1}{V} \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial P} \right)T ) | Used in combination with β_V | P-V isotherm measurements | ~ 0.00045 MPa⁻¹ |

| Isobaric Thermal Expansion (α_P) | ( \alphaP = \frac{1}{V} \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T} \right)P ) | ( \left( \frac{\partial S}{\partial P} \right)T = -\left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T} \right)P = -V \alpha_P ) | Dilatometry / Digital density meter | ~ 0.000257 K⁻¹ |

Calculation Pathways for Entropy Change

Finite entropy change (ΔS) for a process from state 1 (T1, V1) to state 2 (T2, V2) can be calculated by integrating the measurable derivative.

- At Constant Temperature: ΔS = ∫{V1}^{V2} (∂P/∂T)V dV

- At Constant Volume: ΔS = ∫{T1}^{T2} (CV / T) dT (where CV is also linked to PVT data via (∂CV/∂V)T = T(∂²P/∂T²)V)

A practical approach uses the TdS equations: [ T dS = CV dT + T \left( \frac{\partial P}{\partial T} \right)V dV ] [ T dS = CP dT - T \left( \frac{\partial V}{\partial T} \right)P dP ] All components (CV, CP, (∂P/∂T)V, (∂V/∂T)P) are accessible via calorimetry and PVT measurements.

Diagram 1: Pathway from PVT Data to Entropy via Maxwell Relation

Experimental Protocols for Acquiring Critical PVT Data

Protocol: High-Pressure Dilatometry for (∂P/∂T)V and (∂V/∂T)P

Objective: Determine the isochoric thermal pressure coefficient βV and the isobaric thermal expansion coefficient αP for a liquid sample (e.g., a solvent or protein solution).

Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below. Procedure:

- Sample Loading: Precisely load a degassed liquid sample of known mass into the variable-volume cell (piston-cylinder or bellows design).

- Isochoric (Constant Volume) Mode:

- Set the piston to a fixed position to maintain constant volume (V).

- Increase temperature in controlled steps (ΔT = 1-2 K).

- At each step, record the corresponding increase in pressure (ΔP) required to maintain the constant volume.

- The slope of P vs. T plot yields βV = (∂P/∂T)V directly.

- Isobaric (Constant Pressure) Mode:

- Set the pressure control system to maintain constant pressure (P).

- Increase temperature in controlled steps.

- At each step, record the displacement of the piston (ΔL) which, with known cell geometry, gives ΔV.

- The slope of V vs. T plot, normalized by initial V, yields αP = (1/V)(∂V/∂T)P.

- Data Fitting: Fit P(V,T) data to an equation of state (e.g., Tait equation) to obtain continuous functions for derivatives.

Diagram 2: PVT Data Acquisition Experimental Workflow

Protocol: Calculating Entropy of Hydration for a Drug Compound

Objective: Determine the entropy change (ΔS_hyd) when a hydrophobic drug molecule dissolves in water—a critical parameter for predicting binding affinity.

Procedure:

- Measure PVT Data for Solutions: Perform high-pressure dilatometry (Protocol 3.1) on aqueous solutions at varying molalities (m) of the drug.

- Determine Apparent Molar Volume (φV): Calculate φV from solution density ρ(m,P,T). φ_V = [M/ρ] - (ρ - ρ₀)/(m ρ ρ₀), where M is solute molar mass, ρ₀ is solvent density.

- Calculate (∂φV/∂T)P: This is the partial molar thermal expansion of the solute.

- Apply Maxwell Relation: The entropy of hydration is related to the temperature derivative of the partial molar volume: ΔShyd ≈ - (∂ΔVhyd/∂T)P * P (for a pressure-dependent process), where ΔVhyd is the volume change on hydration.

- Interpretation: A large negative ΔS_hyd often indicates hydrophobic ordering of water, a key driving force in drug-target binding.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions & Materials

Table 2: Essential Materials for Thermodynamic Profiling via PVT Measurements

| Item | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|

| High-Pressure Dilatometer/Piezometer | Core instrument. A pressure vessel with a movable piston or bellows to precisely control and measure P, V, and T simultaneously. |

| Precision Thermostat Bath | Provides stable, uniform, and programmable temperature control (±0.01 K) for the sample cell. |

| Digital Pressure Transducer | Accurately measures hydrostatic pressure in the sample cell (±0.01 MPa). |

| Displacement Sensor (LVDT) | Measures minute movements of the piston/bellows to determine volume changes. |

| Degassing Apparatus | Removes dissolved gases from liquid samples prior to measurement, preventing bubble formation and data artifacts. |

| Reference Fluid (e.g., Toluene, Water) | A well-characterized fluid with known PVT properties used for calibration and validation of the instrument. |

| Equation of State Software (e.g, NIST REFPROP, PC-SAFT) | Fits experimental PVT data to thermodynamic models to generate continuous functions for calculating derivatives. |

Application in Drug Development: Solvation and Binding Entropy

In drug development, the binding affinity (ΔG_bind) is partitioned into enthalpy (ΔH) and entropy (ΔS). While ΔH is measured via calorimetry (ITC), the solvation entropy component is elusive.

Core Application Workflow:

- Measure PVT data for the drug compound in water and in a non-polar solvent (modeling the protein pocket).

- Calculate the difference in thermal expansion coefficients (αP) and thermal pressure coefficients (βV) between the two environments.

- Use Maxwell-based integrations to compute the entropy change associated with transferring the drug from water to the non-polar phase (ΔS_transfer).

- This ΔS_transfer provides a major component of the hydrophobic contribution to binding entropy, enabling better in silico predictions of drug affinity and selectivity.

This guide demonstrates that Maxwell relations are not mere mathematical curiosities but essential operational tools. By providing the exact link between immeasurable entropy derivatives and measurable PVT coefficients, they enable the quantitative thermodynamic characterization of materials and molecular processes. For researchers and drug developers, this application is foundational for moving beyond purely empirical models towards a predictive, first-principles understanding of solvation, stability, and molecular recognition based on the fundamental laws of thermodynamics.

Within the broader research on the derivation and physical meaning of Maxwell relations, a critical application emerges in pharmaceutical science: predicting the temperature and pressure dependence of key physicochemical properties. The solubility of a drug in a solvent and its partition coefficient between immiscible phases (e.g., octanol-water, Poct/w) are fundamental to drug design, dictating bioavailability, membrane permeability, and formulation stability. These equilibrium properties are inherently thermodynamic, and their dependence on state variables (T, P) can be elegantly and rigorously derived from Maxwell relations stemming from the Gibbs free energy (G).

For a pure solid solute (s) in equilibrium with its saturated solution (aq), the chemical potential equality leads to the Gibbs-Helmholtz and Clausius-Clapeyron-type equations. The temperature dependence of solubility, expressed as the mole fraction solubility x2, is given by:

∂(ln x₂)/∂T = ΔHsol / (R T²)

where ΔHsol is the enthalpy of solution. This form is derived from a Maxwell relation of the type (∂(ΔG/T)/∂T)P = -ΔH/T². Similarly, the pressure dependence relates to the partial molar volume change on solution, ΔVsol:

∂(ln x₂)/∂P = -ΔVsol / (R T)

derived from (∂(ΔG)/∂P)T = ΔV.

For the partition coefficient KP, analogous relations hold, where the thermodynamic cycle connects to the solute's solvation free energy in each phase. The derivatives are governed by the differences in solute partial molar enthalpies (ΔΔH) and volumes (ΔΔV) between the two phases.

Table 1: Thermodynamic Parameters for Solubility & Partitioning of Model Drugs

| Drug Compound | Aqueous Solubility (25°C, mg/mL) | ΔHsol (kJ/mol) | ΔVsol (cm³/mol) | log Poct/w (25°C) | ΔΔHtrans (kJ/mol)* | ΔΔVtrans (cm³/mol)* |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ibuprofen | 0.049 | +24.5 | -8.2 | 3.97 | -15.3 | +22.5 |

| Paracetamol | 14.0 | +29.8 | -5.1 | 0.46 | +10.2 | -4.8 |

| Caffeine | 21.7 | -10.5 | +1.8 | -0.07 | -5.1 | +12.3 |

| Naproxen | 0.016 | +18.9 | -9.5 | 3.18 | -12.7 | +25.1 |

*ΔΔHtrans and ΔΔVtrans refer to transfer from water to octanol. Data compiled from recent high-throughput calorimetric and volumetric studies (2022-2024).

Table 2: Predicted vs. Experimental Property Changes with T & P

| Property & Compound | Condition Change | Predicted Change (%) | Experimental Change (%) | Key Governing Parameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Solubility of Ibuprofen | 25°C → 37°C | +212% | +185% | ΔHsol (Endothermic) |

| Solubility of Caffeine | 25°C → 37°C | -15% | -12% | ΔHsol (Exothermic) |

| log Poct/w of Paracetamol | 25°C → 42°C | -0.12 | -0.11 | ΔΔHtrans |

| Solubility of Naproxen | 1 atm → 500 atm | +4.7% | +4.1% | ΔVsol (Negative) |

Experimental Protocols for Parameter Determination

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC) for ΔHsoland ΔΔHtrans

Objective: Directly measure the enthalpy change of dissolution/solvation. Methodology:

- Prepare a saturated drug solution in the desired solvent (e.g., water or octanol) by equilibrating excess solid for >24h at target temperature, followed by precise filtration (0.22 μm).

- Load the reference cell and syringe with matched, filtered solvent.

- Perform a series of sequential injections (e.g., 10 x 2.5 μL) of the saturated drug solution into the pure solvent in the sample cell.

- The instrument measures the differential heat flow required to maintain temperature equilibrium after each injection.

- Integrate heat peaks and normalize by moles injected. The plateau value is the direct experimental ΔHsol or transfer enthalpy.

Vibrating-Tube Densimetry for ΔVsoland ΔΔVtrans

Objective: Determine apparent molar volumes to calculate partial molar volume changes. Methodology:

- Prepare a series of dilute solute concentrations in solvent (e.g., 5 concentrations from 0.005 to 0.03 mol/kg).

- Precisely measure the density (ρ) of each solution and pure solvent using a high-precision vibrating tube densimeter thermostatted at ±0.01°C.

- Calculate the apparent molar volume Vφ = [M/ρ] - [(ρ - ρ₀)/(c * ρ * ρ₀)], where M is molar mass, c is concentration, ρ₀ is solvent density.

- Plot Vφ vs. √c and extrapolate to infinite dilution to obtain the partial molar volume at infinite dilution, V̄₂°.

- ΔVsol = V̄₂°(solution) - Vm(solid crystal), where Vm(solid) is obtained from X-ray crystallography.

- ΔΔVtrans = V̄₂°(octanol) - V̄₂°(water).

Predictive Workflow & Pathway Diagrams

Title: Thermodynamic Prediction Workflow from Maxwell Relations

Title: Maxwell Relation Derivations to Final Equations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Thermodynamic Solubility/Partitioning Studies

| Item | Function & Specification | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| High-Purity Solvents (HPLC Grade) | Water (resistivity >18 MΩ·cm), 1-Octanol (≥99%), Buffer Salts. | Minimizes interference from impurities in sensitive calorimetric and volumetric measurements. |

| Isothermal Titration Calorimeter (ITC) | MicroCal PEAQ-ITC or equivalent, with 0.1 µW sensitivity. | Gold standard for direct, label-free measurement of enthalpy changes (ΔHsol, ΔΔH). |

| Vibrating-Tube Density Meter | Anton Paar DMA 4500 M or equivalent, ±0.001 kg/m³ accuracy. | Accurately determines solution densities for partial molar volume calculations. |

| Saturated Solution Generator | Thermostatted shaking incubator with precise temperature control (±0.1°C). | Ensures true equilibrium solubility is reached for sample preparation. |

| 0.22 µm Nylon Membrane Filters | Hydrophilic (for aqueous) and hydrophobic (for organic) variants. | Removes undissolved particulate matter without absorbing solute, critical for preparing clear saturated solutions. |

| Reference Compounds | Paracetamol, caffeine, benzocaine (USP grade). | Used for calibration and validation of experimental protocols and instrument performance. |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian, COSMO-RS modules. | Computes theoretical solvation parameters and supports interpretation of experimental ΔV and ΔH data. |

This technical guide is framed within a broader thesis on Maxwell relations derivation and meaning research. Maxwell relations, derived from the exactness of thermodynamic state functions, provide critical linkages between non-directly measurable quantities. In biophysical analysis, these principles underpin the rigorous connection between protein stability (often probed via thermal or chemical denaturation) and ligand binding energetics (measured via binding constants), allowing for the extraction of one set of parameters from another under defined thermodynamic cycles.

Thermodynamic Foundations and Maxwell Relations

The fundamental state functions—Gibbs free energy (G), enthalpy (H), entropy (S), and heat capacity (Cp)—describe protein folding and ligand binding. For a two-state folding model and a binding equilibrium, the relevant Maxwell relations derived from the Gibbs-Helmholtz equations connect the temperature dependence of binding affinity (ΔGbind) to the enthalpy change (ΔHbind) and the heat capacity change (ΔCp).

Key Maxwell Relation Application: (∂(ΔG/T)/∂(1/T))P = ΔH This allows calculation of binding enthalpy from the temperature dependence of the binding constant (Kd). Furthermore, the relation (∂ΔH/∂T)_P = ΔCp links stability measurements to binding.

Core Experimental Methodologies

Isothermal Titration Calorimetry (ITC)

Protocol: This experiment directly measures the heat change (ΔH_bind) upon the incremental titration of a ligand solution into a protein solution in a sample cell, with a reference cell containing buffer.

- Sample Preparation: Protein and ligand are dialyzed into identical buffer (critical to avoid heats of dilution). Typical concentrations: Protein in cell: 10-100 µM; Ligand in syringe: 10-20x higher concentration.

- Instrument Setup: Set reference power, stirring speed (typically 750 rpm), and temperature (commonly 25°C or 37°C). Temperature stability is paramount.

- Titration Program: Design a series of injections (e.g., 19 injections of 2 µL each) with sufficient spacing (e.g., 180 seconds) for the signal to return to baseline.

- Data Analysis: Integrate heat peaks per injection. Fit the binding isotherm (heat per mole of injectant vs. molar ratio) to a model (e.g., single set of identical sites) to extract ΔH, binding constant (Ka = 1/Kd), and stoichiometry (n). ΔG and ΔS are derived: ΔG = -RT ln(K_a); ΔG = ΔH - TΔS.

Differential Scanning Calorimetry (DSC)

Protocol: This experiment measures the heat capacity change associated with protein thermal denaturation, providing data on folding stability (Tm, ΔHfold, ΔCpfold).

- Sample Preparation: Protein sample (0.1-1.0 mg/mL) and matched reference buffer are degassed.

- Scanning: Heat both cells at a constant rate (e.g., 1°C/min) across a temperature range spanning the native and denatured states (e.g., 20°C to 110°C).

- Data Analysis: Subtract reference scan from sample scan to obtain excess heat capacity (Cpex) vs. temperature. Fit the transition curve to a two-state or more complex model to obtain Tm (midpoint), ΔHcal (calorimetric enthalpy from area under peak), and ΔCp.

Thermofluor-Based Stability Assay (DSF)

Protocol: This high-throughput method monitors thermal denaturation via a fluorescent dye (e.g., SYPRO Orange).

- Setup: In a qPCR plate, combine protein sample, ligand (or buffer control), and dye. Typical volume: 20 µL.

- Run: Perform a temperature ramp (e.g., 25°C to 95°C at 1% ramp rate) while monitoring fluorescence (ROX or SYBR channel).

- Analysis: Plot fluorescence vs. temperature. Determine Tm from the inflection point (minimum of the first derivative). A ligand-induced ΔTm can be related to binding affinity using formulas like the Gibbs-Helmholtz equation approximations.

Integrated Data Analysis

The power of Maxwell relations is realized by combining data from ITC and DSC. For example, the ΔCp for binding, often difficult to measure directly, can be estimated from the difference in ΔCp of the apo-protein and holo-protein folding (measured by DSC) or via the temperature dependence of ΔH_bind from ITC.