Improving Energy Function Accuracy in Protein Design: From Physics-Based Models to AI-Driven Solutions

Accurate energy functions are the cornerstone of reliable computational protein design, enabling the creation of novel therapeutics, enzymes, and materials.

Improving Energy Function Accuracy in Protein Design: From Physics-Based Models to AI-Driven Solutions

Abstract

Accurate energy functions are the cornerstone of reliable computational protein design, enabling the creation of novel therapeutics, enzymes, and materials. This article explores the critical advancements and persistent challenges in refining these functions, moving from traditional physics-based and statistical potentials to modern machine learning and game theory approaches. We provide a comprehensive analysis for researchers and drug development professionals, covering foundational principles, methodological innovations like RFDiffusion and ProteinMPNN, strategies for troubleshooting multi-body interactions and electrostatics, and rigorous validation protocols. By synthesizing insights from foundational research and cutting-edge applications, this review serves as a guide for developing more robust, accurate, and generalizable energy functions to power the next generation of protein design breakthroughs.

The Foundations of Energy Functions: From Physical Principles to Statistical Potentials

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the fundamental limitation of physics-based energy functions in protein design? Physics-based energy functions, such as those used in platforms like Rosetta, rely on approximations and pairwise decomposable terms (e.g., Lennard Jones, hydrogen bonding, electrostatics). Even minor inaccuracies in these energy estimates can result in designed proteins that misfold or fail to perform their intended function. Furthermore, exhaustive conformational sampling is often computationally prohibitive, limiting the practical exploration of the protein sequence-structure space [1] [2].

FAQ 2: How can I determine if my designed protein will fold into the intended structure? A common method is to use deep learning-based structure prediction tools, such as AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold, to assess the designed sequence. A significant discrepancy (high Cα RMSD) between the structure predicted from the sequence alone and your original design model indicates a high probability of a "Type I failure," where the sequence does not adopt the intended monomer structure. The pLDDT confidence metric from these tools is also highly indicative of folding success [2].

FAQ 3: My design has a favorable Rosetta energy, but it fails experimentally. What are other common failure modes? Beyond folding failures ("Type I"), a second common failure mode is a "Type II failure," where the designed monomer folds correctly but does not bind the target as intended. This can be assessed by using AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold to predict the complex structure between your designed binder and the target. A high predicted Aligned Error (pAE) or high Cα RMSD in the predicted complex compared to your design model suggests an interface failure [2].

FAQ 4: What strategies can improve the success rate of my de novo protein designs? Augmenting traditional energy-based design with deep learning filters has been shown to increase success rates nearly tenfold. This involves:

- Using ProteinMPNN for more efficient and robust sequence design.

- Using AlphaFold2 or RoseTTAFold to filter for designs likely to fold correctly (high pLDDT).

- Using the same tools to filter for designs likely to form the correct target complex (low interface pAE) [2].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Designs Are Not Folding as Intended (Type I Failures)

Symptoms: Expressed protein is insoluble, shows incorrect oligomerization state, or has a circular dichroism spectrum that does not match the designed secondary structure content.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate Energy Function | Check if Rosetta energy was the sole filter. Calculate the Cα RMSD and pLDDT between your design model and an AlphaFold2 prediction of the sequence [2]. | Implement a deep learning filter. Discard designs with low pLDDT (< a certain threshold, e.g., 80-85) or high Cα RMSD (> ~1.5Å) for the monomer [2]. |

| Insufficient Negative Design | The energy function stabilizes the desired state but fails to destabilize competing, misfolded states. | Incorporate evolution-guided design principles. Restrict sequence choices to those found in natural homologs to avoid aggregation-prone or misfolding-prone motifs [3]. |

Problem: Designs Fold but Do Not Bind the Target (Type II Failures)

Symptoms: Protein is expressed and monomeric but shows no binding affinity in assays like Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI).

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Inaccurate Interface Energy | Rosetta ddG may be favorable, but the interface is not physically realistic. | Use a complex prediction protocol with AlphaFold2 (e.g., with an initial guess from your design). Designs with high interface pAE or high Cα RMSD should be discarded [2]. |

| Incomplete Conformational Sampling | The designed interface may be geometrically incompatible when full side-chain and backbone flexibility are considered. | Use molecular dynamics (MD) simulations to probe for transient cryptic pockets and assess interface stability. Methods like Mixed-Solvent MD can identify realistic binding hotspots [4]. |

Quantitative Data on Energy Function & Design Success

The following table summarizes key metrics from a study that evaluated the use of deep learning to augment Rosetta-based binder design, highlighting the performance of different assessment methods [2].

Table 1: Performance of Different Metrics in Discriminating Successful Binders from Failures

| Assessment Method | Application Scope | Predictive Power for Success | Key Metric(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Energy | Monomer Folding | Low | Normalized energy per residue |

| DeepAccuracyNet (DAN) | Monomer Folding | Moderate | Monomer accuracy score |

| AlphaFold2 pLDDT | Monomer Folding | High | pLDDT (per-residue & average) |

| Rosetta ddG | Complex Binding | Moderate | Interface ΔΔG |

| AlphaFold2 pAE | Complex Binding | High | Interface pAE (Predicted Aligned Error) |

Experimental Validation Protocols

Protocol: Validating a De Novo Designed Protein Binder

This protocol outlines key steps to experimentally validate the fold and function of a computationally designed protein, based on common practices in the field.

Objective: To confirm that a designed protein:

- Folds into the intended monomeric structure (Addressing Type I Failure).

- Binds the target protein with the predicted affinity and specificity (Addressing Type II Failure).

Materials:

- Purified designed protein (binder)

- Purified target protein

- Size-Exclusion Chromatography (SEC) system with Multi-Angle Light Scattering (SEC-MALS)

- Circular Dichroism (CD) Spectropolarimeter

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR) or Bio-Layer Interferometry (BLI) instrument

- Crystallization screens or materials for Cryo-Electron Microscopy (if structural validation is planned)

Methodology:

- Expression and Purification:

- Express the designed protein in a suitable host (e.g., E. coli for simplicity, or eukaryotic cells if required for folding).

- Purify using affinity chromatography (e.g., His-tag) followed by size-exclusion chromatography (SEC).

Biophysical Characterization for Folding (Type I Check):

- SEC-MALS: Determine the monodispersity and precise molecular weight of the designed protein in solution. This confirms it is a stable monomer and not aggregated or oligomeric.

- Circular Dichroism (CD): Acquire a far-UV CD spectrum. Compare the observed secondary structure composition (alpha-helix, beta-sheet) to the proportions in the design model.

- Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR): For smaller proteins, NMR can provide high-resolution data on folding and dynamics.

Functional Characterization for Binding (Type II Check):

- SPR/BLI: Measure the binding kinetics (association rate

k_on, dissociation ratek_off) and equilibrium dissociation constant (K_D) between the designed binder and the immobilized target protein. - Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay (ELISA): Use a qualitative or semi-quantitative binding assay to confirm specific interaction.

- SPR/BLI: Measure the binding kinetics (association rate

High-Resolution Structural Validation (Gold Standard):

- X-ray Crystallography or Cryo-EM: Solve the atomic structure of the designed protein, either alone or in complex with its target. A low Cα RMSD between the experimental structure and the design model is the ultimate validation of success.

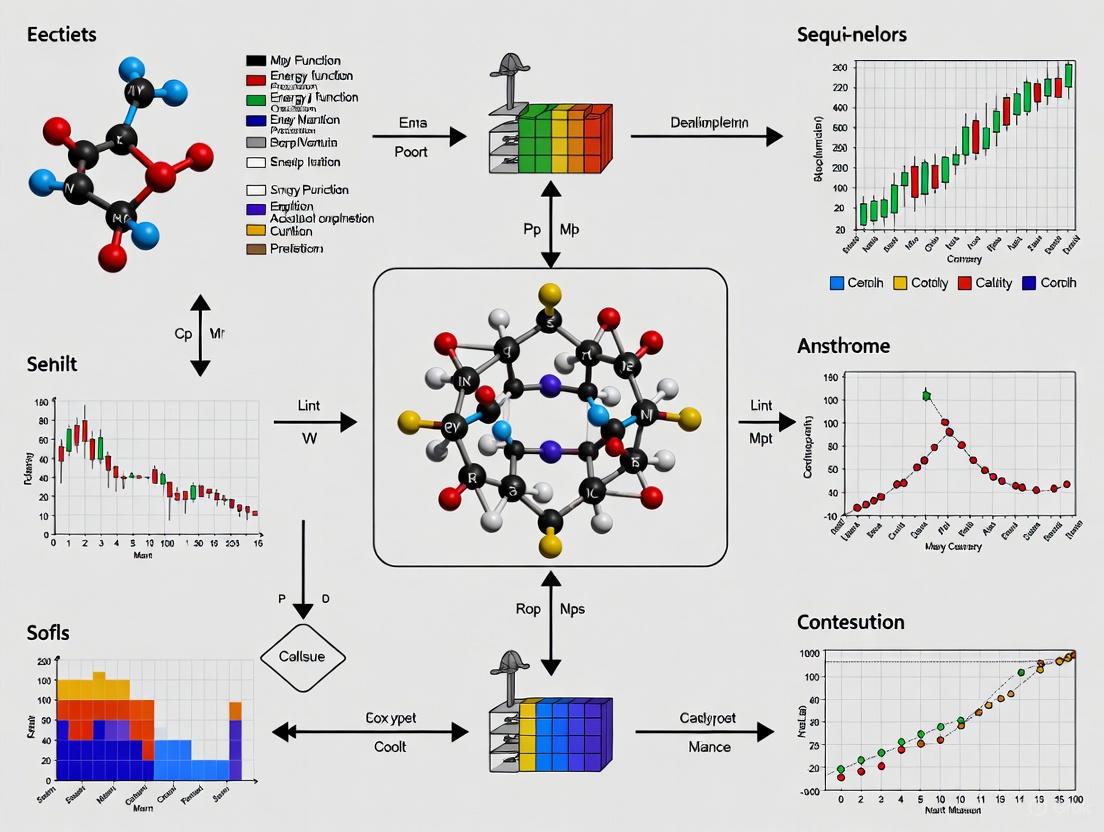

Visualization of Failure Modes and Validation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the two primary failure modes in de novo protein design and the corresponding computational checks to diagnose them.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational and Experimental Tools for Protein Design Validation

| Item | Function / Application | Role in Troubleshooting Energy Functions |

|---|---|---|

| Rosetta Software Suite | A comprehensive platform for macromolecular modeling, including de novo protein design and energy-based scoring. | Provides the initial design framework and physics-based energy function (e.g., full-atom refinement, ddG calculations) that requires subsequent validation [1] [2]. |

| AlphaFold2 & RoseTTAFold | Deep learning networks for highly accurate protein structure prediction from amino acid sequence. | Used as a filter to identify Type I and Type II failures by predicting the actual structure of the designed monomer and its complex with the target [2]. |

| ProteinMPNN | A deep learning-based protein sequence design tool. | Can be used as an alternative to Rosetta for sequence design, offering increased computational efficiency and robustness [2]. |

| Molecular Dynamics (MD) Software (e.g., GROMACS, AMBER) | Simulates the physical movements of atoms and molecules over time. | Used to probe protein dynamics, assess stability, and identify transient cryptic pockets that static structures miss, providing a dynamic check on energy landscapes [4]. |

| SEC-MALS (Size-Exclusion Chromatography with Multi-Angle Light Scattering) | An analytical technique to determine the absolute molecular weight and oligomeric state of a protein in solution. | Critically validates that the designed protein is monodisperse and folded as a monomer, a key check against aggregation or misfolding (Type I failure). |

| SPR/BLI (Surface Plasmon Resonance / Bio-Layer Interferometry) | Label-free techniques for real-time analysis of biomolecular interactions, providing kinetic and affinity data (K_D, k_on, k_off). |

The primary method for experimentally confirming that the designed binder interacts with its target with the expected affinity, validating against Type II failures [2]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is CHARMM and what are its primary applications in research? CHARMM (Chemistry at HARvard Macromolecular Mechanics) is a versatile molecular simulation program used for atomic-level simulation of many-particle systems. It is primarily applied to biological systems including peptides, proteins, prosthetic groups, small molecule ligands, nucleic acids, lipids, and carbohydrates in solution, crystals, and membrane environments. CHARMM also finds applications in materials design for inorganic materials and supports multi-scale techniques like QM/MM, MM/CG, and various implicit solvent models [5].

Q2: What makes CHARMM suitable for protein design research? CHARMM provides a comprehensive set of energy functions, enhanced sampling methods, and supports the integration of molecular dynamics within protein design. Tools like PROTDES, which is based on CHARMM, allow researchers to automatically mutate residue positions and find optimal amino acids in protein structures while optimizing folding free energy. This enables the creation of customized protein design procedures using different energy functions [6].

Q3: Can CHARMM be used with other molecular dynamics software? Yes, CHARMM force fields can be used with other MD programs such as GROMACS, NAMD, and AMBER. For GROMACS users, CHARMM36 force field files are regularly made available in GROMACS format through the MacKerell lab website [7] [8].

Q4: What are common issues when preparing PDB files for CHARMM calculations? Common PDB file errors include unrecognized water residue names (use HOH or TIP3), incorrect disulfide bond information, missing chain IDs, and ligands incorrectly using ATOM instead of HETATM. Files prepared with VMD may eliminate TER records, which must be added manually to distinguish chains [9].

Q5: How does CHARMM handle force field parameters for drug-like molecules? The CHARMM General Force Field (CGenFF) covers a wide range of chemical groups in biomolecules and drug-like molecules, including many heterocyclic scaffolds. However, users are cautioned against using CGenFF for molecules where specialized force fields already exist (e.g., proteins, nucleic acids) [10].

Troubleshooting Guides

PDB File Reading Failures

Problem: CHARMM fails to read your PDB file.

Solutions:

- Check Water Residues: Ensure water residues are named either

HOH(RCSB format) orTIP3(CHARMM format) [9]. - Verify TER Records: A

TERrecord must separate water from any other residue type and distinguish between different chains [9]. - Inspect Ligand Records: Ligand molecules must use

HETATMrecords rather thanATOMrecords [9]. - Confirm Chain Information: RCSB-formatted PDB files must contain chain IDs, and atoms within the same chain must be written consecutively [9].

Ligand Parameterization Issues

Problem: Errors occur when generating force field parameters for ligands.

Solutions:

- Match Atom Ordering: Ensure the order of atoms in your PDB file exactly matches the order in your Mol2 or SDF file. Mismatches can cause atom positions to become mixed during simulations [9].

- Verify Residue Names: When using SDF files from the RCSB database, the residue name in your PDB must match the RCSB ligand entry ID [9].

- Check Protonation States and Bond Orders: Explicitly add hydrogen atoms according to the desired protonation state in your Mol2/SDF file, as bond orders are used to determine proper atom types [9].

- Review Topology/Parameter Files: Check for missing atom types in your topology (

.rtf) and parameter (.prm) files by comparing with correct examples [9].

System Generation and Simulation Failures

Problem: Membrane system size errors or simulation failures.

Solutions:

- Check Membrane System Size: For membrane systems, ensure at least 4 lipids exist between the primary and image proteins. Inspect the

step3_packing.pdbfile to verify [9]. - Neutralize System Charge: Add counterions like K+ to neutralize the system charge when introducing anionic ligands [11].

- Rebuild Modified Systems: If adding non-standard components (e.g., anionic ligands), rebuild the entire system in CHARMM-GUI to ensure consistent topologies and parameters rather than modifying existing files [11].

- Handle Large Systems: CHARMM-GUI currently supports systems up to 3 million atoms. Monitor your system size accordingly [9].

Key Energy Functions and Parameters

The CHARMM force field uses a potential energy function that includes both bonded and non-bonded terms [10] [12]. The following table summarizes the key components:

Table 1: Components of the CHARMM Additive Force Field Potential Energy Function

| Energy Term | Mathematical Expression | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Bonds | $Kb(b - b0)^2$ | Harmonic potential for covalent bond stretching |

| Angles | $K{\theta}(\theta - \theta0)^2$ | Harmonic potential for angle bending between three connected atoms |

| Dihedrals | $K_{\chi}[1 + \cos(n\chi - \delta)]$ | Cosine-based potential for torsion angles around bonds |

| Impropers | $K{\text{imp}}(\phi - \phi0)^2$ | Harmonic potential for out-of-plane bending (e.g., to maintain planarity) |

| Urey-Bradley | $K{UB}(S - S0)^2$ | Harmonic potential for 1,3 non-bonded atoms (optional) |

| Non-Bonded | $\epsilon{ij}\left[\left(\frac{R{\text{min}{ij}}}{r{ij}}\right)^{12} - 2\left(\frac{R{\text{min}{ij}}}{r{ij}}\right)^6\right] + \frac{qi qj}{\epsilonr r_{ij}}$ | Lennard-Jones (vdW) and Coulombic (electrostatic) interactions |

Solvation Models in Protein Design

The PROTDES toolbox for CHARMM implements three distinct solvation models for calculating folding free energy in protein design, each with different computational characteristics [6]:

Table 2: Solvation Models Available in the PROTDES CHARMM Toolbox

| Model | Type | Key Features | Energy Formulation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Generalized Born using Molecular Volume (GBMV) | Implicit Solvent | Includes electrostatic screening and hydrophobic term; based on Generalized Born equation | $E{\text{sol}} = \sum{i \neq j} E{\text{screen}{ij}} + \sumi \Delta E{\text{self}i} + \sumi \Delta E{\text{nonp}i}$ |

| Accessible Surface Area (ASA) | Empirical | Linear relationship between solvation energy and solvent-exposed surface area | $E{\text{sol}} = \sumi \sigmai \text{ASA}i$ |

| Effective Energy Function (EEF1) | Implicit Solvent | Excluded volume model with empirical screening of solvation energy density | $E{\text{sol}} = \sumi \Delta Gi^{\text{ref}} \times fi$ |

Experimental Protocols

PROTDES Workflow for Computational Protein Design

The PROTDES package provides a CHARMM-based methodology for automatically mutating residue positions and identifying optimal amino acid sequences for a target protein structure [6]. The following diagram illustrates the main workflow:

Title: PROTDES Protein Design Workflow

Procedure:

Initial Setup:

- Input a protein structure file (PDB format).

- Define the set of residue positions to be mutated and the allowed amino acids at each position.

Energy Function Selection:

Rotamer Sampling and Optimization:

- Generate a library of possible side-chain conformations (rotamers) for each design position.

- An heuristic optimization algorithm (e.g., Monte Carlo Simulated Annealing, MCSA) iteratively searches for the best amino acids and their conformations.

- The algorithm minimizes the total potential energy of the system, which includes the CHARMM22 force field terms (electrostatics, van der Waals) and the selected solvation energy [6].

Advanced Option: Incorporating Backbone Flexibility:

- PROTDES allows integration of molecular dynamics simulations to introduce backbone flexibility.

- By default, this involves energy minimization and dynamics of the region within a 9 Å sphere surrounding the Cα atom of each designed position, allowing local structural adjustments [6].

Output:

- The procedure outputs the amino acid sequences identified as having the lowest folding free energy for the target structure.

GROMACS Simulation with CHARMM36 Force Field

For researchers using the CHARMM36 force field in GROMACS, specific settings are required to ensure compatibility and accuracy [8]:

Configuration (mdp file) Settings:

| Parameter | Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|

| constraints | h-bonds |

Constrains all bonds involving hydrogen atoms |

| cutoff-scheme | Verlet |

Uses the modern Verlet cutoff scheme |

| vdwtype | cutoff |

Specifies a straight cutoff for vdW interactions |

| vdw-modifier | force-switch |

Applies a force-switching function between rvdw-switch and rvdw |

| rlist | 1.2 |

Neighbor list update cutoff (1.2 nm) |

| rvdw | 1.2 |

vdW interaction cutoff (1.2 nm) |

| rvdw-switch | 1.0 |

Distance at which vdW switching begins (1.0 nm) |

| coulombtype | PME |

Particle Mesh Ewald for long-range electrostatics |

| rcoulomb | 1.2 |

Real space electrostatic cutoff (1.2 nm) |

| DispCorr | no |

No dispersion correction for lipid bilayers |

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item/Software | Type | Primary Function | Application in Protein Design |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM Program | MD Software | Performs energy minimization, molecular dynamics, and analysis [5] | Core simulation engine for energy calculations and protein design protocols |

| CHARMM-GUI | Web-Based Platform | Interactively builds complex molecular systems and generates inputs [13] | Prepares simulation systems for proteins, membranes, and ligand complexes |

| PROTDES | CHARMM Toolbox | Automates protein sequence design and mutation optimization [6] | Identifies low-energy amino acid sequences for target protein structures |

| CHARMM36 Force Field | Parameter Set | Defines all-atom empirical energy function parameters [10] [12] | Provides physically realistic energy evaluations for biomolecules |

| CGenFF | Parameter Set | CHARMM General Force Field for drug-like molecules [10] | Generates parameters for novel ligands and small molecules in protein-ligand studies |

| GBMV/ASA/EEF1 | Solvation Model | Implicit solvent models for solvation free energy [6] | Accounts for solvent effects in folding free energy calculations during protein design |

Statistical Energy Functions (SEFs) are computational tools derived from the known sequence and structure data of natural proteins. They are designed to capture the complex relationships between amino acid sequences and their corresponding three-dimensional folds. Unlike physics-based models that rely on molecular mechanics force fields, SEFs leverage statistical analysis of existing protein databases to identify evolutionary and structural patterns that dictate foldability. The primary goal of SEFs is to improve the accuracy and efficiency of computational protein design, enabling researchers to create novel proteins for therapeutic and biotechnological applications.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs) and Troubleshooting

Q1: What is the fundamental difference between a Statistical Energy Function (SEF) and a physics-based energy function like the one used in Rosetta?

A1: The core difference lies in the source of their parameters. Physics-based functions, such as those in RosettaDesign, are primarily derived from molecular mechanics force fields and fundamental physical principles. In contrast, SEFs are "comprehensive" functions derived from statistical analysis of known protein sequences and structures in databases. They aim to capture evolutionary and structural relationships that may not be fully represented by current physical models. The SEF developed under the SSNAC strategy, for example, was shown to design sequences that are highly diverse from RosettaDesign solutions yet still fold correctly, indicating it captures complementary aspects of protein sequence-structure relationships [14].

Q2: My SEF-designed protein sequence is not folding correctly in experimental validation. What could be the primary reasons?

A2: Several factors in the SEF methodology and subsequent handling could be at fault. Consult the following troubleshooting table for specific issues and recommendations.

| Problem Area | Specific Issue | Recommended Action |

|---|---|---|

| Energy Function & Sampling | Inadequate treatment of side-chain packing or solvation. | Consider using an extended SEF that incorporates van der Waals energy (e.g., ESEF_v) for finer packing details [14]. |

| Limited sequence diversity in the solution space. | The SSNAC-based SEF has been shown to produce sequences with low identity to Rosetta designs; verify that your function leverages this complementarity [14]. | |

| Experimental Validation | Intrinsic low foldability of the designed sequence. | Implement the TEM1-β-lactamase experimental selection system to assess foldability and evolve stability in vivo [14]. |

| Proteolysis of unfolded proteins in experimental systems. | The TEM1-β-lactamase system specifically links proteolysis of unfolded proteins to antibiotic resistance, providing a direct readout on foldability [14]. |

Q3: How can I quickly assess whether a computationally designed protein will be well-folded without resorting to extensive structural analysis?

A3: A highly efficient experimental method involves using an engineered TEM1-β-lactamase system. In this approach [14]:

- The protein of interest (POI) is inserted into the β-lactamase gene with glycine/serine-rich linkers.

- This construct is expressed in bacteria.

- If the POI is poorly folded, it is targeted by periplasmic proteases, leading to degraded β-lactamase and low antibiotic resistance.

- Well-folded POIs result in functional β-lactamase and high antibiotic resistance. This system provides a selectable phenotype for foldability, allowing for rapid assessment and even directed evolution to rescue problematic designs.

Q4: Our SEF performs well on all-α protein targets but fails on targets containing β-strands. How can we improve its performance?

A4: This is a recognized challenge. Theoretical tests have shown that while some design methods struggle with β-containing targets, a well-constructed SEF can surpass the performance of physics-based models in these cases. To improve your SEF [14]:

- Re-examine the Training Data: Ensure your SEF's statistical derivation includes a sufficient number and diversity of all-β and α/β protein folds.

- Refine Pairwise Terms: The interactions governing β-sheet formation are critical. Review and refine the residue pairwise terms in your SEF, potentially using the SSNAC strategy to more accurately handle the joint structural properties relevant for β-sheet formation.

- Validate with Ab Initio Prediction: Use ab initio structure prediction (e.g., Rosetta ab initio) on your designed sequences as a theoretical validation step before moving to experiments. A low TM-score between predicted structures and your design target indicates a problem with the sequence [14].

Key Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Protocol: De Novo Protein Design Using a Statistical Energy Function

This protocol outlines the key steps for designing a novel protein sequence for a target backbone structure using an SEF.

1. Target Backbone Selection:

- Choose a stable, desired protein backbone structure from the PDB or from a de novo designed model.

- Targets of 76–191 residues spanning different fold classes (all-α, all-β, α/β, α+β) have been successfully used [14].

2. Sequence Design via Energy Minimization:

- Using your SEF (e.g., one built with the SSNAC strategy), compute the statistical energy for amino acid sequences placed onto the fixed target backbone.

- The SEF typically includes single-residue and residue-pairwise terms. The SSNAC strategy avoids pre-defined bins for structural properties, instead using adaptive neighbor selection for more accurate probability estimations [14].

- Perform a computational search for sequences that minimize the total SEF energy.

3. In Silico Validation:

- Ab Initio Structure Prediction: Subject the designed sequence to ab initio tertiary structure prediction (e.g., using Rosetta ab initio). Generate hundreds of models.

- Structure Similarity Analysis: Compare the predicted models to the original design target using a metric like the Template Modeling Score (TM-score). A successful design will have a high fraction of predicted models with a TM-score >0.5, indicating the sequence's inherent propensity to fold into the target structure [14].

4. Experimental Validation of Foldability:

- TEM1-β-lactamase Selection: Clone the designed sequence into the TEM1-β-lactamase selection system and transform into appropriate E. coli cells. Plate cells on media containing increasing concentrations of ampicillin. Colonies growing at high antibiotic concentrations likely express well-folded designs [14].

- Structural Analysis: For designs passing the selection, express and purify the protein without the β-lactamase fusion. Determine the high-resolution structure using techniques like NMR spectroscopy or X-ray crystallography to confirm agreement with the design target [14].

Diagram 1: SEF Protein Design and Validation Workflow.

Protocol: Assessing SEF Performance vs. Physics-Based Models

To objectively compare the performance of a new SEF against an established method like RosettaDesign, follow this benchmarking protocol.

1. Benchmark Set Curation:

- Select a diverse set of ~40 native protein backbone structures from the PDB, covering all major structural classes [14].

2. Parallel Sequence Design:

- For each target backbone, design three sequences using your SEF.

- For the same targets, design three sequences using a physics-based method like Rosetta fixed backbone design [14].

3. Performance Metrics Calculation:

- Sequence Diversity: Calculate the average sequence identity between SEF-designed sequences and native sequences, and between SEF-designed and Rosetta-designed sequences. A good SEF should produce native-like sequences (~30% identity) that are distinct from physics-based solutions [14].

- Theoretical Foldability: Perform ab initio structure prediction for all designed sequences. Calculate the percentage of predicted models with TM-score >0.5 for each group (SEF, Rosetta, Native). A higher percentage indicates better performance [14].

- Energy Evaluation: Use both the SEF and the Rosetta energy function to evaluate all designed sequences and the native sequences under the target structure. A robust SEF should assign lower energies to native sequences than to poorly designed ones [14].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The following table details key resources for conducting protein design experiments with Statistical Energy Functions.

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in SEF-Related Research |

|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) | A primary source of known protein structures used to derive statistical potentials and to provide target backbones for design and benchmarking [14]. |

| Statistical Energy Function (SEF) | The core computational tool, e.g., one built with the SSNAC strategy, used to score and select amino acid sequences that are compatible with a target structure [14]. |

| TEM1-β-lactamase Plasmid System | An experimental vector for assessing protein foldability in vivo. Unfolded designs lead to proteolysis and low antibiotic resistance, while folded designs confer high resistance [14]. |

| Rosetta Software Suite | A versatile software package used for comparative tasks, including physics-based sequence design (RosettaDesign) and ab initio structure prediction to validate designed sequences [14]. |

| Structure Prediction Metrics (TM-score) | A quantitative measure for assessing the structural similarity between a computational model (e.g., from ab initio prediction) and the design target. Critical for in silico validation [14]. |

Advanced Analysis and Data Interpretation

Quantitative Comparison of SEF and RosettaDesign Performance

The following table summarizes key results from a theoretical benchmark on 40 diverse protein targets, highlighting the complementary strengths of an SEF approach [14].

| Performance Metric | Native Sequences | SEF-designed Sequences | Rosetta-designed Sequences |

|---|---|---|---|

| Avg. Sequence Identity to Native | 100% | ~30% | ~30% |

| Avg. Sequence Identity to Rosetta Designs | N/A | < 30% | 100% |

| Avg. Secondary Structure Agreement | 83% | 86% | 81% |

| Theoretical Foldability (Fraction of models with TM-score > 0.5) | Highest | Intermediate (Superior to Rosetta on β-strand targets) | Lower |

Diagram: SSNAC Strategy for Enhanced SEF Accuracy

The SSNAC (Selecting Structure Neighbours with Adaptive Criteria) strategy addresses key limitations in traditional SEFs for protein design.

Diagram 2: SSNAC Strategy for SEF Development.

What is the SSNAC strategy and how does it address key limitations of previous statistical energy functions (SEFs)?

The Selecting Structure Neighbours with Adaptive Criteria (SSNAC) strategy is a general method for developing comprehensive statistical energy functions (SEFs) for protein design. It was created to overcome critical problems that plagued earlier SEFs, which often estimated probability distributions based on a prior discretization of structural properties into a few discrete categories or bins [14].

This pre-discretization approach caused two main issues:

- Estimation Bias: Target properties falling near the boundary of pre-defined intervals (e.g., solvent accessibility categories or distance bins) led to significant biases in probability estimations.

- Multidimensional Treatment Difficulty: It was difficult to treat multiple or multi-dimensional structural properties jointly with decent accuracy [14].

The SSNAC strategy solves these problems by estimating conditional distributions of amino acid types from training data selected as "neighbours" to a target point in a space spanned by multiple structural properties. This allows for the straightforward consideration of different structural properties as joint conditions. It uses adaptive cutoffs for training data selection to balance the amount and relevance of the data and incorporates a special likelihood-range-based procedure to correct for small sample size effects [14].

How does the performance of an SSNAC-based SEF compare to established physics-based models like RosettaDesign?

The SSNAC-based SEF provides a complementary and often superior approach to established physics-based models. Theoretical tests involving the redesign of sequences for 40 native protein backbones showed that while sequences designed with the SEF had similar sequence identities to native proteins (~30%) as those designed with Rosetta fixed backbone design, they were significantly different from the Rosetta-designed sequences (also below 30% identity) [14].

A key performance metric is the results of ab initio structure prediction on the designed sequences. When the predicted models were compared to the design targets using TM-score, the sequences designed using the SEF (ESEF_v) led to a significantly higher fraction of target-like predicted models (TM-score >0.5) than sequences designed with Rosetta, especially for targets containing β-strands [14].

Furthermore, energy evaluations revealed a crucial insight: the SEF predicted that most of the results from Rosetta fixed backbone design for non-all-α targets had significantly higher sequence energies than the corresponding native sequences. This suggests the SEF captures certain energy contributions that favor native sequences over designs from a leading physics-based method [14].

Table 1: Performance Comparison of SSNAC-based SEF vs. RosettaDesign

| Aspect | SSNAC-based SEF (ESEF_v) | RosettaDesign |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Identity to Native | ~30% (similar to native) [14] | ~30% (similar to native) [14] |

| Sequence Identity Between Methods | <30% sequence identity with Rosetta designs [14] | <30% sequence identity with SEF designs [14] |

| Ab initio Prediction Success | Significantly higher fraction of target-like models (TM-score >0.5) [14] | Lower fraction of target-like models, especially for β-strand targets [14] |

| Energy Evaluation of Designs | Predicts Rosetta designs for non-all-α targets have higher energy than native [14] | N/A |

What experimental validation exists for proteins designed using the SSNAC strategy?

The SSNAC strategy, combined with experimental feedback, has successfully produced well-folded de novo proteins. Researchers reported four de novo proteins for different targets that were all experimentally verified to be well-folded [14]. The solution structures for two of these designed proteins were solved using NMR and were found to be in excellent agreement with their respective design targets, providing strong validation for the accuracy of the design method [14].

A critical component of this success was the use of an experimental method to assess and improve the foldability of the designed proteins. This approach used an engineered TEM1-β-lactamase system where the structural stability of a protein of interest is linked to the antibiotic resistance of bacteria expressing it. This system efficiently identified which designed proteins were well-folded and could select mutations that rescued initially problematic designs, providing critical feedback for improving the computational models [14].

How do I implement a basic SSNAC strategy for a protein design project?

The following workflow outlines the core steps for implementing the SSNAC strategy to develop and use a statistical energy function.

Experimental Protocol: SSNAC-based Protein Design and Validation

Objective: To design a novel amino acid sequence for a target backbone structure using an SSNAC-based SEF and experimentally validate the design.

Materials:

- Target Backbone: A predefined protein backbone structure (e.g., from PDB or a de novo design).

- Training Dataset: A curated set of high-resolution protein structures from the PDB for training the SEF [14].

- Computational Tools: Software for structural analysis and SEF implementation (e.g., custom code based on the SSNAC strategy).

- Validation System: An experimental system for assessing foldability, such as the TEM1-β-lactamase selection system for in vivo stability screening, and/or resources for structural validation like NMR or X-ray crystallography [14].

Methodology:

- SEF Construction:

- For your target backbone, analyze each residue's structural environment using multiple properties (e.g., solvent accessibility, backbone torsion angles, etc.).

- Implement the SSNAC strategy: For each target residue's specific multi-dimensional structural property set, select neighboring residues from the training dataset using adaptive cutoffs to ensure sufficient, relevant data.

- From these selected neighbors, estimate the conditional probability distribution for each amino acid type.

- Apply a correction for small sample sizes to refine the probability estimates.

- Compile these learned terms into a comprehensive SEF [14].

Sequence Design:

- Use the constructed SEF in a fixed-backbone design protocol to find amino acid sequences that minimize the statistical energy for the target structure. This often involves stochastic optimization algorithms to explore the sequence space [14].

Experimental Validation:

- Primary Screening: Clone the designed sequences into the TEM1-β-lactamase selection system. Transform into appropriate bacterial cells and plate on media containing increasing concentrations of ampicillin (or another β-lactam antibiotic). Well-folded designs will confer higher resistance [14].

- Characterization: Express and purify proteins from stable, resistant clones. Analyze their secondary structure using circular dichroism (CD) spectroscopy.

- High-Resolution Validation: For the most promising designs, determine the three-dimensional structure using solution NMR or X-ray crystallography. Compare the solved structure to the initial design target to assess accuracy [14].

What are common pitfalls when using statistical potentials and how can the SSNAC strategy help avoid them?

Table 2: Common Pitfalls in Statistical Potentials and SSNAC Solutions

| Common Pitfall | Description | How SSNAC Strategy Addresses It |

|---|---|---|

| Discretization Bias | Pre-binning structural properties leads to inaccurate probability estimates for values near bin boundaries. | Uses adaptive neighbor selection in continuous multi-dimensional space, eliminating arbitrary bins [14]. |

| Poor Handling of Multi-Dimensional Conditions | Difficulty in accurately representing joint probabilities of multiple structural properties. | Directly estimates conditional distributions in a space spanned by multiple structural properties jointly [14]. |

| Low Data Relevance | Using all available training data can introduce noise if much of it is structurally dissimilar to the target. | Adaptive cutoffs select only the most structurally relevant "neighbor" data for each target point [14]. |

| Small Sample Size Errors | Estimates can be unreliable when few data points match a specific structural context. | Employs a special likelihood-range-based procedure to correct for effects of small sample sizes [14]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for SSNAC-Based Design Experiments

| Research Reagent / Material | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|

| Protein Data Bank (PDB) Structures | Serves as the essential source of high-resolution protein structures for training the statistical energy function and deriving structural relationships [14]. |

| TEM1-β-lactamase Selection System | An in vivo experimental tool that links the structural stability of a protein of interest (POI) to bacterial antibiotic resistance, allowing for high-throughput assessment and optimization of designed protein foldability [14]. |

| Statistical Energy Function (ESEF/ESEF_v) | The computational model built using the SSNAC strategy. It evaluates the compatibility of an amino acid sequence with a target backbone structure, guiding the sequence design process [14]. |

| NMR Spectroscopy | A high-resolution experimental technique used to determine the three-dimensional solution structure of a designed protein, providing the ultimate validation by comparing it to the design target [14]. |

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

FAQ: Why do my designed proteins show high stability but lack functional activity?

- Issue: A common problem in inverse folding, where redesigning a protein's sequence for a single, stable structure often disrupts functionally critical residues or conformational dynamics.

- Solution: Utilize multimodal inverse folding models like ABACUS-T, which integrate multiple backbone conformational states and evolutionary information from multiple sequence alignments (MSA). This helps preserve residues essential for functional dynamics and substrate recognition, ensuring that redesigned proteins (e.g., enzymes like β-xylanase or β-lactamase) maintain or even enhance catalytic activity while achieving substantial gains in thermostability (∆Tm ≥ 10 °C) [15].

FAQ: How can I improve the predictive accuracy of my energy function for novel protein sequences?

- Issue: Physics-based forcefields can be inaccurate, and models trained solely on evolutionary data may not generalize well to novel, non-natural sequences.

- Solution: Incorporate biophysics-based protein language models like METL (Mutational Effect Transfer Learning). These models are pre-trained on synthetic data from molecular simulations, capturing fundamental biophysical attributes such as van der Waals interactions, solvation energies, and hydrogen bonding. This approach provides a biophysically grounded representation that excels in low-data settings and extrapolation tasks, improving predictions for stability and function [16].

FAQ: My energy calculations seem to exaggerate steric repulsion, leading to overly conservative designs. How can I adjust for this?

- Issue: The fixed-backbone and rotamer approximations used in many design energy functions can lead to excessive steric repulsion energies, which do not reflect the flexibility and slight adjustments possible in real protein structures.

- Solution: Modify the van der Waals potential within your energy function. As demonstrated with the EGAD energy function, calibrating the vdW parameters using protein-protein complex affinities as a basis set can compensate for this issue. This adjustment, requiring only two modified vdW parameters and an overall proportionality constant, can produce designs with higher native sequence identity and improved metrics for structural specificity and solubility [17].

FAQ: What is the best way to model electrostatic and solvation effects without prohibitive computational cost?

- Issue: Explicitly modeling every water molecule and ion is computationally expensive for large-scale screening or design.

- Solution: Employ continuum solvation models. These methods treat the solvent as a continuous dielectric medium (with a high dielectric constant, e.g., ~80 for water) rather than individual molecules. This provides a robust and computationally efficient framework for estimating electrostatic solvation free energies, which are critical for understanding biomolecular folding, binding, and catalysis [18].

FAQ: How critical is hydrogen bonding in ensuring the structural specificity of a designed protein?

- Issue: Designed proteins may fold correctly but might also populate alternative, non-native low-energy states.

- Solution: Explicitly include "negative design" for solubility and specificity in your energy function. This involves using simple physical models to penalize the formation of compact non-native structures and aggregation. Ensuring that hydrogen bonding potential is satisfied in the native state while being frustrated in non-native states is a key strategy to improve conformational specificity and prevent misfolding [17].

Quantitative Data on Energy Components

Table 1: Key Energy Components in Protein Design Forcefields

| Energy Component | Physical Basis & Role | Common Modeling Approach | Considerations for Accuracy |

|---|---|---|---|

| Van der Waals | Determinants of close-range packing and shape complementarity in protein-ligand and protein-protein complexes [19]. | Lennard-Jones potential, which estimates attraction and repulsion between atoms [19]. | Excessive repulsion from fixed-backbone approximations may require parameter adjustment [17]. |

| Electrostatics | Long-range interactions between charged and polar groups; fundamental for folding, stability, and molecular recognition [20]. | Coulomb's law, often combined with continuum solvation models to describe screening by water and ions [18]. | Accuracy depends on correct assignment of protonation states and accounting for electronic and nuclear polarization [18]. |

| Solvation | Energetic effect of immersing a molecule in a solvent (e.g., water). Includes polar (electrostatic) and nonpolar (hydrophobic) components [18]. | Continuum models (Poisson-Boltzmann, Generalized Born) for polar part; surface area models for nonpolar part [18]. | Nonpolar solvation involves the hydrophobic effect and interactions with uncharged solutes [18]. |

| Hydrogen Bonding | Special, directional electrostatic interaction between a hydrogen donor and an acceptor. Important for secondary structure formation and molecular specificity [20]. | Often modeled as an electrostatic interaction, sometimes with added angular constraints or specific potential terms. | A key metric for design success is minimizing unsatisfied hydrogen bonds in the native state [17]. |

Table 2: Performance of Advanced Computational Models in Protein Engineering

| Model Name | Core Methodology | Key Integrated Features | Documented Experimental Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABACUS-T [15] | Multimodal inverse folding using denoising diffusion in sequence space. | Atomic sidechains & ligands, protein language model (ESM), multiple backbone states, MSA evolutionary information. | Redesigned proteins showed ≥10°C ∆Tm increase with maintained or enhanced activity; high-affinity binders achieved. |

| METL [16] | Transformer-based PLM pre-trained on biophysical simulation data. | Learned representations of protein sequence, structure, and energetics (vdW, solvation, H-bond) from Rosetta simulations. | Excelled in low-data tasks (e.g., designing functional GFP from 64 examples) and position extrapolation. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol: Utilizing a Multimodal Inverse Folding Model (ABACUS-T) for Functional Protein Redesign

This protocol outlines the steps for using the ABACUS-T model to redesign a protein sequence for enhanced thermostability while preserving its biological function [15].

Input Preparation:

- Structure: Obtain the experimental or predicted protein backbone structure(s) in PDB format.

- Ligands (Optional): If the protein function involves a substrate, cofactor, or other small molecule, provide its atomic structure in the bound state.

- Multiple Conformational States (Optional): If the protein's function involves conformational dynamics (e.g., an allose binding protein), provide multiple backbone structures representing key states.

- Multiple Sequence Alignment (MSA): Generate an MSA of homologous sequences to provide evolutionary constraints.

Model Execution:

- The ABACUS-T model employs a sequence-space denoising diffusion probabilistic model (DDPM).

- The process starts from a fully "noised" (masked) sequence and performs successive reverse diffusion steps.

- At each step, the model decodes both residue types and sidechain conformations, conditioned on the provided structural and evolutionary inputs. It uses self-conditioning with the output from the previous step to refine the sequence.

Output and Analysis:

- The model generates a set of candidate amino acid sequences that are predicted to fold into the target backbone.

- These sequences typically contain dozens of simultaneous mutations relative to the wild type.

Experimental Validation:

- Synthesize and express a small number (e.g., 3-5) of the top-designed sequences.

- Measure thermostability (e.g., via melting temperature, ∆Tm) and functional activity (e.g., catalytic activity for an enzyme, binding affinity for a binder).

- Successful designs should show a significant increase in thermostability (e.g., ∆Tm ≥ 10 °C) while maintaining or surpassing wild-type functional levels [15].

Protocol: Fine-Tuning a Biophysics-Based Protein Language Model (METL)

This protocol describes how to adapt the METL framework to predict a specific protein property, such as thermostability or catalytic activity, from a limited set of experimental data [16].

Synthetic Pretraining Data Generation (METL Framework):

- For a protein of interest, generate millions of sequence variants with random amino acid substitutions (e.g., up to 5 mutations).

- Model the 3D structure of each variant using a tool like Rosetta.

- For each modeled structure, compute a set of ~55 biophysical attributes, including van der Waals interactions, solvation energies, and hydrogen bonding.

Model Pretraining:

- A transformer encoder neural network is pretrained to predict the computed biophysical attributes from the amino acid sequence alone.

- This step forces the model to learn an internal representation of protein sequences that is grounded in biophysical principles.

Experimental Data Fine-Tuning:

- Collect a small dataset of experimental sequence-function pairs for your target protein (e.g., 64 variants for GFP).

- Use this experimental data to fine-tune the pretrained METL model. The model's parameters are updated to learn the mapping between its biophysical representation and the new experimental outcome.

Prediction and Design:

- The fine-tuned model can now input new, unseen protein sequences and predict the target property (e.g., fluorescence intensity, stability).

- This model can be used to screen in silico for sequence variants with enhanced properties before moving to experimental testing.

Workflow and Relationship Visualizations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Energy Function-Based Protein Design

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ABACUS-T [15] | Multimodal Inverse Folding Model | Redesigns protein sequences from a backbone structure, integrating evolutionary and ligand data to preserve function while boosting stability. | Functional enzyme and binding protein engineering. |

| METL [16] | Biophysics-Based Protein Language Model | Pre-trained on molecular simulations; fine-tuned with small experimental datasets to predict variant properties like thermostability and activity. | Property prediction and design in low-data regimes. |

| Rosetta [16] [1] | Software Suite for Macromolecular Modeling | Provides energy functions for structure prediction and design; used for generating structural variants and biophysical data for model training. | Physics-based structural modeling and de novo design. |

| EGAD Energy Function [17] | Physics-Based Energy Function | An all-atom forcefield for protein design, calibrated against protein-protein affinities to correct for excessive steric repulsion. | Physics-based sequence design for various folds. |

| Continuum Solvation Models [18] | Computational Electrostatics Method | Efficiently calculates electrostatic solvation free energies by modeling solvent as a dielectric continuum, crucial for binding and stability calculations. | Implicit solvent calculations in folding and docking. |

| Protein Repair & Analysis Server [21] | Web Server | Prepares protein structures for computation by adding missing atoms, repairing structures, and assigning secondary elements. | Pre-processing PDB files before design or analysis. |

The GMEC Assumption and its Implications for Design Accuracy

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What is the GMEC, and why is its accurate identification crucial for my protein design experiments?

The Global Minimum Energy Conformation (GMEC) is the single lowest-energy conformation of a protein sequence threaded onto a target backbone structure. Accurately identifying the GMEC is fundamental to computational protein design, as it is the structure that the designed protein is predicted to adopt. The reliability of your design predictions—whether for creating novel enzymes, therapeutics, or stable scaffolds—depends entirely on the accurate computation of this state [22] [23]. An incorrect GMEC prediction can lead to a non-functional protein, as the designed sequence may not fold as intended or perform the desired activity.

Q2: My designs are not folding correctly in the lab, even though computational predictions were strong. Could the "sparse GMEC" be the issue?

This is a common troubleshooting point. Many design algorithms use sparse residue interaction graphs, which apply distance or energy cutoffs to ignore interactions between residues that are far apart. This makes the computation faster and more manageable. However, this process results in a "sparse GMEC," which can be different from the true "full GMEC" that considers all pairwise interactions [22] [23].

The neglected long-range interactions can have a cumulative effect, leading to:

- Sequence Differences: The sparse and full GMECs can select for different amino acid identities at key positions.

- Structural & Functional Changes: The loss of these favorable interactions can alter the local environment, leading to structural instability and loss of function [22].

Q3: How significant are the differences between the sparse GMEC and the full GMEC?

The differences are non-trivial and have been quantitatively demonstrated. A study of 136 protein design problems showed that the use of common distance cutoffs can result in a GMEC with a different sequence than the full GMEC [22] [23]. The table below summarizes the potential impacts.

Table 1: Impacts of Sparse vs. Full Residue Interaction Graphs on GMEC Prediction

| Aspect | Impact of Sparse GMEC | Experimental Consequence |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence | Different amino acid identity at mutable positions [22] [23] | Designed protein has an incorrect sequence and may not express or fold. |

| Energy | Overall energy of the predicted conformation is inaccurate [22] | Inability to accurately rank designs or estimate stability. |

| Conformation | Altered local interactions and side-chain packing [22] | The protein adopts an unintended structure with compromised function. |

Q4: Are some types of protein residues more affected by these cutoffs than others?

Yes. The impact of using sparse interaction graphs depends critically on the location of the design within the protein structure [22] [23].

- Core Residues: Designs involving core residues are highly sensitive to cutoffs due to their dense, tightly-packed interactions.

- Surface Residues: Designs on the surface can also be significantly affected, especially when electrostatic or other long-range interactions are important for function or binding. Neglecting these long-range interactions can inadvertently alter the very local interactions you are trying to design [22].

Q5: How can I improve the accuracy of electrostatics and solvation in my energy function?

Simple, pairwise-decomposable electrostatics models that use a distance-dependent dielectric constant are common but can fail to accurately capture the balance of interactions, particularly for buried polar groups or surface ion pairs [24]. More accurate approaches use Generalized Born (GB) continuum models or similar methods to approximate the Poisson-Boltzmann equation, which more faithfully reproduces solvation energies and electrostatic interactions [24]. Incorporating such environment-dependent models is crucial for designing systems that rely on delicately balanced interactions, such as conformational switches or specific protein-protein interfaces [24].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Designs Exhibit Low Thermostability or Aggregation

Potential Cause: Inaccurate GMEC prediction due to neglected long-range interactions or an inadequate energy function that fails to properly penalize misfolded states.

Solution:

- Compute Both GMECs: Use a provable algorithm to compute the GMEC for both the full and sparse residue interaction graphs. Research shows that for 6 design problems with experimental thermostability data, the sparse and full GMECs predicted different stabilizing mutations, with no clear trend on which was better [23]. Calculating both provides a more complete picture.

- Implement Energy-Bounding Enumeration: This method uses a provable algorithm to generate a gap-free list of the top low-energy conformations (e.g., the first 1,000) from the sparse graph calculation. The full GMEC is almost always found within this small set and can be identified with minimal additional computation [22] [23]. This allows you to reap the computational benefits of the sparse graph while avoiding its potential inaccuracies.

- Validate with Ensemble-Based Design: Instead of relying solely on the GMEC, use algorithms that approximate the thermodynamic ensemble. This helps account for backbone and side-chain flexibility, providing a more realistic assessment of the protein's behavior in solution [22].

The following workflow diagram illustrates this robust troubleshooting process:

Problem: Failure to Design Functional Binding Sites or Enzyme Active Sites

Potential Cause: The energy function lacks the accuracy to capture the subtle balance of interactions required for functional sites, particularly concerning buried polar groups and electrostatic contributions.

Solution:

- Incorporate Advanced Electrostatics: Move beyond simple Coulombic models with constant dielectrics. Implement a Generalized Born (GB) model or similar continuum dielectric model to more accurately calculate solvation and electrostatic energies [24].

- Combine Sequence- and Structure-Based Information: Leverage evolution-guided design. Analyze the natural diversity of homologous sequences to filter design choices, which implicitly implements negative design against misfolding. Follow this with atomistic, positive design to stabilize your target structure within this evolutionarily informed sequence space [3].

- Utilize Paired MSAs for Complex Design: When designing protein-protein interfaces, the construction of deep paired Multiple Sequence Alignments (pMSAs) can provide critical inter-chain co-evolutionary signals that guide the prediction of successful complexes, going beyond simple sequence similarity [25].

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Energy Function Accuracy

| Reagent / Tool | Type | Primary Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| OSPREY | Software Suite | Implements provable algorithms (DEE/A*) for GMEC computation and ensemble-based design, allowing direct comparison of sparse vs. full GMECs [22] [23]. |

| EGAD | Software & Energy Function | A protein design program that incorporates a fast and accurate approximation for Born radii, enabling more precise calculation of electrostatics and solvation energies [24]. |

| Rotamer Library | Data Resource | A discrete set of frequently observed, low-energy side-chain conformations. Used to model flexibility and reduce conformational search space [22] [24]. |

| Generalized Born (GB) Model | Computational Method | A continuum solvation model that provides a good approximation of Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatics, crucial for accurate energy evaluations [24]. |

| Paired Multiple Sequence Alignments (pMSAs) | Data Resource / Method | Alignments constructed by pairing homologs across interacting protein families. Used to capture inter-chain co-evolutionary signals for complex structure prediction [25]. |

The logical relationship between energy function components and design outcomes is summarized below:

Methodological Advances: Integrating Machine Learning and Novel Algorithms

Troubleshooting Guide: AI-Driven Protein Design

This guide addresses common challenges researchers face when using machine learning tools for protein design, with a focus on improving energy function accuracy.

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My AlphaFold2 or AlphaFold3 model shows high confidence but fails experimental validation, particularly in flexible regions. How can I improve accuracy?

AlphaFold models are trained on static structural data and often represent a single, low-energy conformation, which can oversimplify flexible regions [26].

- Solution: Use ensemble prediction methods to sample multiple conformations.

- Protocol: Implement tools like AFsample2, which perturbs AlphaFold2's input Multiple Sequence Alignments (MSAs) by randomly masking portions to reduce bias toward a single structure [26].

- Workflow:

- Run AFsample2 with multiple MSA masking seeds.

- Generate a diverse set of plausible structures (an ensemble).

- Cluster the generated ensembles and analyze conformational diversity, particularly in loops and binding interfaces.

- Expected Outcome: In benchmark tests, AFsample2 improved the prediction of alternate state models in 9 out of 23 cases and found alternative conformations in 11 of 16 membrane transport proteins [26].

Q2: How can I accurately predict the binding affinity of a designed protein-ligand complex without resorting to costly simulations?

Traditional methods like Free Energy Perturbation (FEP) are computationally expensive, taking 6-12 hours per simulation [26].

- Solution: Utilize new models that unify structure prediction and affinity estimation.

- Protocol: Employ Boltz-2, an open-source foundation model that co-folds a protein-ligand pair to output both the 3D complex and a binding affinity estimate [26].

- Workflow:

- Input your protein and ligand sequences into a Boltz-2 interface (e.g., Nano Helix platform).

- Run the joint structure-and-affinity prediction (takes ~20 seconds on a single GPU).

- Use the estimated binding affinity (pKd/IC50) to prioritize designs for experimental testing.

- Expected Outcome: Boltz-2 achieves a ~0.6 correlation with experimental binding data at a fraction of the cost and time of FEP [26].

Q3: My designed protein complex, especially an antibody-antigen pair, has poor interface accuracy despite using state-of-the-art predictors. What can I do?

Standard MSA pairing strategies can fail for complexes that lack clear inter-chain co-evolutionary signals, such as antibody-antigen or virus-host systems [25].

- Solution: Leverage methods that use sequence-derived structural complementarity instead of relying solely on co-evolution.

- Protocol: Apply the DeepSCFold pipeline, which predicts protein-protein structural similarity (pSS-score) and interaction probability (pIA-score) directly from sequence [25].

- Workflow:

- Input your protein complex sequences into DeepSCFold.

- The pipeline constructs deep paired MSAs using predicted structural similarity and interaction probability.

- These paired MSAs are fed into a complex structure predictor (e.g., AlphaFold-Multimer) to generate the final model.

- Expected Outcome: DeepSCFold demonstrated a 24.7% higher success rate for antibody-antigen binding interfaces compared to AlphaFold-Multimer and 12.4% compared to AlphaFold3 [25].

Q4: I need to design a novel protein binder from scratch. What is a reliable generative AI workflow?

De novo binder design requires generating both a backbone structure and a sequence that folds into that structure.

- Solution: Combine a structure diffusion model with a sequence design network.

- Protocol: Use RFdiffusion for backbone generation, followed by ProteinMPNN for sequence design [27].

- Workflow:

- Conditional Generation: In RFdiffusion, specify your target (e.g., a protein surface for binding) as a conditioning input.

- Backbone Generation: Run RFdiffusion to generate diverse protein backbone structures that satisfy your conditioning.

- Sequence Design: For each generated backbone, use ProteinMPNN to design multiple sequences that are predicted to fold into that structure.

- In-silico Validation: Validate the final designs using a structure predictor like AlphaFold2 or ESMFold.

- Expected Outcome: This workflow has been experimentally validated to produce stable, functional binders. A cryo-EM structure of a designed binder in complex with influenza haemagglutinin was nearly identical to the design model [27].

Q5: How can I design or model Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs), which are poorly handled by standard tools like AlphaFold?

Approximately 30% of human proteins are disordered, and AlphaFold is trained on static structures, making it ill-suited for flexible IDPs [28].

- Solution: Use physics-based models optimized with machine learning.

- Protocol: Employ a method that uses automatic differentiation to optimize protein sequences for desired properties based on molecular dynamics simulations [28].

- Workflow:

- Define the target property (e.g., propensity to form loops, response to a environmental cue).

- The algorithm computes how small changes in the amino acid sequence affect this property via automatic differentiation.

- It efficiently searches the sequence space to find candidates that match the target behavior based on physical simulations.

- Expected Outcome: This approach allows for the design of differentiable protein sequences with tailored dynamic properties, bridging a critical gap left by current AI tools [28].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Generating Conformational Ensembles with AFsample2

- Objective: To sample multiple biologically relevant conformations of a protein beyond the single state predicted by standard AlphaFold2.

- Software Requirements: AFsample2 installation, HHblits or MMseqs2 for MSA generation.

- Steps:

- Generate a standard MSA for your protein sequence.

- Run AFsample2, specifying the number of models (e.g., 50-100) and different random seeds for MSA masking.

- Cluster the resulting PDB files using a metric like RMSD on regions of interest.

- Select cluster centroids for analysis or experimental testing.

- Validation: Compare predicted conformational diversity to experimental data (e.g., NMR) if available [26].

Protocol 2: De Novo Binder Design with RFdiffusion and ProteinMPNN

- Objective: To computationally generate a novel protein that binds a specific target.

- Software Requirements: RFdiffusion, ProteinMPNN, AlphaFold2 or ESMFold.

- Steps:

- Define the Target: Prepare a structure file (PDB) of your target molecule. Identify the binding site residues.

- Condition RFdiffusion: Configure RFdiffusion in "binder design" mode, providing the target structure and site as conditioning information.

- Generate Scaffolds: Run RFdiffusion to produce hundreds of candidate binder backbone structures.

- Design Sequences: For each backbone, run ProteinMPNN to generate 8-10 sequences.

- Filter and Validate: Use AlphaFold2 or ESMFold to predict the structure of each designed sequence in complex with the target. Select models with high confidence (pLDDT/pAE) and a complementary interface [27].

Performance Metrics and Data Comparison

Table 1: Comparative Accuracy of Protein Complex Prediction Tools on CASP15 Targets

| Method | Key Feature | Reported Improvement (vs. Baseline) | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| DeepSCFold [25] | Uses sequence-derived structure complementarity | +11.6% TM-score vs. AlphaFold-Multimer; +10.3% vs. AlphaFold3 | Antibody-antigen complexes, targets with weak co-evolution |

| AlphaFold3 [26] | Predicts biomolecular complexes (proteins, DNA, ligands) | ≥50% accuracy improvement on protein-ligand/nucleic acid interactions vs. prior methods | General-purpose complex prediction, multi-molecule systems |

| Boltz-2 [26] | Jointly predicts structure and binding affinity | ~0.6 correlation with experiment; near-parity with FEP at seconds/run | Rapid screening of drug candidates, affinity estimation |

Table 2: Generative AI Models for De Novo Protein Design

| Tool | Type | Input | Output | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RFdiffusion [27] | Structure Diffusion Model | Target coordinates, symmetry, motifs | Protein backbone structures | De novo binders, symmetric assemblies, motif scaffolding |

| ProteinMPNN [26] | Sequence Design Network | Protein backbone structure | Protein sequences that fold into that structure | Fixing sequences for RFdiffusion/AI-generated backbones |

| Automatic Differentiation for IDPs [28] | Physics-based Optimizer | Desired dynamic property | Protein sequences | Designing intrinsically disordered proteins with custom behaviors |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: RFdiffusion Binder Design Workflow

Diagram 2: DeepSCFold Complex Prediction Logic

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for AI-Driven Protein Design

| Item / Software | Function | Typical Use Case | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| AlphaFold Server [26] | Protein structure prediction | Predicting single-chain structures or complexes (AF3) | Free online server for non-commercial use |

| RFdiffusion [27] | Generative backbone design | Creating novel protein binders or scaffolds | Open source (Baker Lab) |

| ProteinMPNN [26] [27] | Protein sequence design | Fixing sequences for AI-generated structures | Open source |

| Boltz-2 [26] | Structure & affinity prediction | Rapid screening of protein-ligand binding | Open source (MIT license) |

| DeepSCFold [25] | Protein complex modeling | Predicting challenging complexes like antibodies | Method described in literature |

| ESMFold [29] | Fast protein structure prediction | High-throughput structure prediction, orphan proteins | Open source (Meta) |

Inverse Folding with ProteinMPNN and ESM-IF for Sequence Optimization

Troubleshooting Guides and FAQs

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My ProteinMPNN outputs contain nonsense sequences with many repetitive amino acids or problematic cysteines. How can I fix this?

This is a known issue, particularly with certain protein complexes. You can apply the following techniques to bias the model's outputs:

- Fix Specific Positions: Increase the number of amino acids that are "fixed" or visible to the model during inference. Fixing domains, specific chains, or a random percentage of positions provides enough bias to correct the output. It is especially useful to fix positions that form loops and other flexible regions, as ProteinMPNN sometimes places rigid or disruptive amino acids there [30].

- Exclude Problematic Amino Acids: You can directly bias the model to exclude specific amino acids from all predictions. For example, to prevent cysteines from appearing in undesired positions, specify

Cin the "Excluded Amino Acids" field if your interface supports it [30].

Q2: How can I optimize my designed sequences for enhanced solubility?

A specialized version of ProteinMPNN, explicitly trained on soluble proteins, is available for this purpose. This tailored model predicts protein variants that maintain similar structures but exhibit higher solubility. To use this, select the 'soluble' model version if you are running ProteinMPNN through a platform like Neurosnap [30].

Q3: What is the most reliable way to validate and select the best sequences generated by an inverse folding model?

A robust validation pipeline involves a two-step process:

- Initial Filtering by Model Score: Filter the generated sequences by the model's inherent confidence metric. For ProteinMPNN, this is the

Score; sequences with values closer to zero generally represent more reliable predictions [30]. - Structure Prediction and Comparison: Take the top candidates from the initial filter and predict their 3D structures using a tool like AlphaFold2 or ESMFold [31]. Then, calculate a structural similarity metric, such as the TM-score, between the predicted structure of your designed variant and the original target structure. Proteins with similar structures tend to have similar functions, making this a strong indicator of success [30] [31].

Q4: How do I choose between an autoregressive model like ProteinMPNN and a non-autoregressive model?

The choice involves a trade-off between inference speed and design strategy.

- ProteinMPNN (Autoregressive): Generates sequences one amino acid at a time in a specific order. This can be slower for large proteins but offers high designability [32].

- Non-Autoregressive Models (e.g., based on Discrete Diffusion): Generate all amino acids in a sequence simultaneously. A key advantage is a significant increase in inference speed (e.g., up to 23 times faster than ProteinMPNN) while maintaining comparable performance on benchmarks. These models also offer flexibility by allowing you to modulate the number of denoising steps to balance between speed and accuracy [32].

Q5: My design problem has multiple, competing objectives (e.g., stabilizing multiple conformational states). How can inverse folding help?

Standard inverse folding can be integrated into broader multi-objective optimization frameworks. One powerful approach is to use evolutionary algorithms (e.g., NSGA-II) where inverse folding models like ProteinMPNN and protein language models like ESM-1v are used as "mutation operators" to propose new sequence candidates. These candidates are then evaluated against multiple objective functions, such as confidence scores from AlphaFold2 for different structural states. This framework allows you to explicitly approximate the Pareto front, finding optimal sequences that represent the best trade-offs between all your design specifications [33].

Performance and Benchmarking

Independent evaluations of deep learning-based protein sequence design methods use a diverse set of indicators to assess performance beyond simple sequence recovery [31]. The table below summarizes key quantitative metrics from a systematic evaluation of eight widely used methods.

Table 1: Key Performance Indicators for Evaluating Protein Sequence Design Methods [31]

| Indicator | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Sequence Recovery | Similarity between the designed sequences and the native sequence. | Higher recovery indicates better replication of native sequence features. |

| Sequence Diversity | Average pairwise difference between designed sequences. | Higher diversity indicates exploration of a broader sequence space. |

| Structure RMSD | Root-Mean-Square Deviation of the predicted structure from the target structure. | Lower RMSD indicates higher structural fidelity of the designed sequence. |

| Secondary Structure Score | Similarity between the predicted secondary structure and the native. | Higher scores indicate better preservation of secondary structural elements. |

| Nonpolar Amino Acid Loss | Measures the inappropriate placement of nonpolar amino acids on the protein surface. | Lower loss indicates a more biologically rational amino acid distribution. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Standard Inverse Folding and Validation Workflow

This protocol describes the core methodology for using inverse folding models like ProteinMPNN and validating their outputs [30] [31].

- Input Structure Preparation: Obtain the desired 3D backbone structure (e.g., from a PDB file or a de novo designed structure). The input typically consists of the coordinates for the backbone atoms (N, Cα, C, O) and, optionally, Cβ.

- Sequence Generation: Run the inverse folding model (e.g., ProteinMPNN or ESM-IF1) using the prepared structure as input. Generate a large number of candidate sequences (e.g., 100-500) to adequately sample the sequence space.