Harnessing Large Gene Clusters: Direct Cloning Strategies for Natural Product Discovery and Synthetic Biology

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest direct cloning strategies designed to capture large biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), crucial for mining novel natural products like antibiotics and chemotherapeutics.

Harnessing Large Gene Clusters: Direct Cloning Strategies for Natural Product Discovery and Synthetic Biology

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the latest direct cloning strategies designed to capture large biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), crucial for mining novel natural products like antibiotics and chemotherapeutics. It explores the foundational principles of techniques such as RecE/RecT recombineering and CRISPR-Cas12a-based methods, detailing their application in heterologous expression and drug discovery. The content further offers practical troubleshooting guidance for common cloning challenges and discusses rigorous validation and comparative frameworks to evaluate method performance, equipping researchers and drug development professionals with the knowledge to advance genomic and synthetic biology applications.

The Foundation of Large-Fragment Cloning: Principles, Challenges, and Evolutionary Drivers

Defining Direct Cloning and Its Role in Accessing Biosynthetic Diversity

The microbial world represents a vast and largely untapped reservoir of natural products with immense potential for drug discovery. These compounds, often possessing complex structures and significant bioactivities, are synthesized by Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs)—groups of clustered genes in bacteria, fungi, and some plants that encode the machinery for secondary metabolite production [1] [2]. Large-scale genome-mining analyses have revealed that microbes potentially harbor a huge reservoir of uncharacterized BGCs [3]. However, a major challenge persists: the majority of these BGCs are silent (or cryptic) and are not expressed under standard laboratory conditions, making their corresponding natural products inaccessible for traditional discovery methods [4] [3]. This gap between genetic potential and characterized metabolites has driven the development of innovative strategies to access this hidden biosynthetic diversity.

Direct cloning has emerged as a pivotal genomic technique for the capture and heterologous expression of large, intact DNA fragments containing BGCs. It is defined as a methodology that enables the direct isolation of a specific, large DNA segment—often tens of kilobytes in size—from a source organism's genome and its subsequent assembly into a vector suitable for transfer and expression in a surrogate host [5] [3]. This strategy is particularly powerful because it bypasses the native host's regulatory constraints that often silence BGCs. By placing the cloned cluster in a genetically tractable, optimized heterologous host, researchers can activate the silent pathway and discover the novel compounds it produces [4]. Direct cloning is thus a cornerstone of modern heterologous host-based genome mining, providing a universal and enabling technology to prioritize the vast and ever-increasing number of uncharacterized BGCs identified in sequencing projects [3].

The Imperative for Direct Cloning in Natural Product Discovery

The drive to develop and refine direct cloning methodologies stems from the significant limitations of traditional approaches to BGC characterization and natural product discovery.

- The Problem of Silent BGCs: Genomic sequencing consistently reveals that Streptomyces and other prolific producers harbor a significantly larger number of BGCs than the number of identified natural products, suggesting that numerous clusters remain minimally expressed or completely inactive [4]. For instance, a study on Streptomyces thermolilacinus SPC6 uncovered 20 typical secondary metabolic BGCs, one of which,

dmx, was identified as completely silent until directly cloned and expressed in a heterologous host, leading to the discovery of a new lanthipeptide, dmxorosin [4]. - Limitations of In-Situ Activation Methods: While methods like promoter engineering, manipulation of global regulators, and the One Strain Many Compounds (OSMAC) strategy can sometimes activate silent BGCs in their native hosts, they are often hit-or-miss and not universally applicable [4]. When these approaches fail, isolating the biosynthetic gene cluster for heterologous expression becomes necessary [4].

- Advantages over Traditional Construction: Direct cloning is distinguished from earlier methods that relied on the painstaking, step-by-step in vitro assembly of a BGC from synthesized parts. By capturing the native cluster directly from genomic DNA (gDNA), direct cloning preserves the cluster's innate genetic architecture, including its native promoters, regulatory elements, and codon usage, which can be critical for successful expression. This makes it a faster and more faithful route to accessing biosynthetic diversity.

Core Principles and Methodological Framework of Direct Cloning

The execution of a direct cloning experiment, regardless of the specific technique, requires the resolution of three fundamental issues [3]. The table below outlines these core steps and their objectives.

Table 1: The Three Fundamental Issues in Direct Cloning of BGCs

| Step | Core Objective | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Genomic DNA (gDNA) Preparation | To obtain high-quality, high-molecular-weight gDNA from the source organism. | DNA integrity is paramount; shearing must be minimized to preserve large DNA fragments containing the entire BGC. |

| 2. BGC Fragment Liberation | To precisely digest and release the intact target BGC from the genomic context. | Requires precise digestion at bilateral boundaries; methods range from restriction enzyme-based to homology-assisted. |

| 3. Vector Assembly | To ligate the liberated BGC fragment into a suitable capture vector. | The vector must be replicable in the heterologous host and often contains selectable markers and elements for genetic manipulation. |

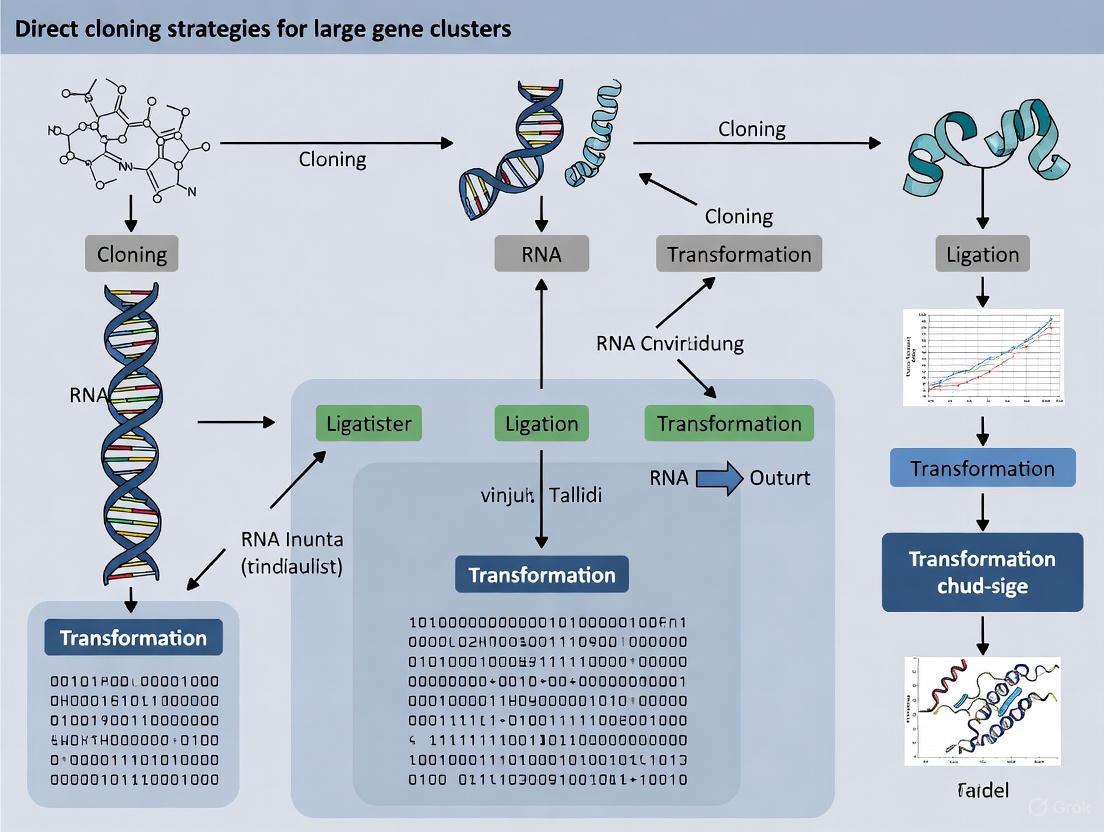

The following diagram illustrates the logical workflow and decision points in a generalized direct cloning strategy.

Key Methodologies for Direct Cloning

Several highly effective methods have been established to address the core challenges of direct cloning.

- Red/ET Recombination (Recombination-Mediated Genetic Engineering): This is a powerful E. coli-based method that uses bacteriophage-derived proteins to mediate highly efficient homologous recombination between linear DNA fragments. In the context of direct cloning, short homology arms (50 base pairs) are added to the ends of the target BGC via PCR. These arms correspond to sequences in the linearized capture vector. When co-introduced into an E. coli strain expressing the Red/ET proteins, the BGC fragment recombines into the vector, seamlessly capturing the cluster [4]. This method was successfully used to directly clone the 23.5 kilobase pair (kbp)

dmxBGC from Streptomyces thermolilacinus [4]. - Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR): TAR is a yeast-based cloning system that exploits the innate homologous recombination machinery of Saccharomyces cerevisiae. The method involves co-transforming gDNA alongside a linearized capture vector into yeast cells. The capture vector contains "hooks"—homology arms that target the regions flanking the desired BGC. Inside the yeast nucleus, the endogenous recombination systems assemble the circular plasmid by linking the vector to the target genomic fragment, effectively cloning the BGC directly from the gDNA mixture.

- CRISPR-Cas Assisted Cloning: The precision of CRISPR-Cas systems has been harnessed for direct cloning. For example, an in vitro protocol using CRISPR-Cas12a has been developed for the direct cloning of large DNA fragments [5]. In this approach, Cas12a ribonucleoproteins (RNPs) are programmed to make double-strand cuts at specific sites flanking the BGC, precisely liberating the fragment from the genome for subsequent capture. This method offers high specificity and flexibility.

Application Notes: A Protocol for Direct Cloning and Heterologous Expression

This protocol outlines the key steps for direct cloning of a BGC using Red/ET recombination, based on a successful case study [4].

Protocol: Direct Cloning of a BGC via Red/ET Recombination

Objective: To isolate a silent ~23 kbp lanthipeptide BGC (e.g., dmx) from Streptomyces thermolilacinus SPC6 and express it heterologously in a suitable Streptomyces host.

Materials: Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Direct Cloning

| Reagent / Material | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Source Organism gDNA | High-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from the organism harboring the target BGC (e.g., S. thermolilacinus SPC6). Serves as the template for cloning. |

| Linearized Capture Vector | A bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) or other suitable vector, linearized to contain homology arms for Red/ET recombination. Provides the backbone for BGC propagation and selection. |

| E. coli GBdir-red Strain | An engineered E. coli strain that inducibly expresses the Red/ET recombination proteins. Essential for facilitating the homologous recombination event. |

| PCR Reagents | For amplifying homology arms and potentially the entire BGC if a "capture" approach is used. |

| Electrocompetent E. coli Cells | For high-efficiency transformation of the recombined plasmid after the Red/ET reaction. |

| Heterologous Host Strains | Genetically tractable surrogate hosts (e.g., S. coelicolor, S. lividans). Must be easily transformable and provide a compatible biosynthetic background for BGC expression. |

Experimental Workflow:

Bioinformatic Analysis and Primer Design:

- Identify the exact boundaries of the target BGC (e.g.,

dmx) using genome mining tools like antiSMASH [1]. - Design PCR primers to amplify approximately 50 base pair homology arms corresponding to the very beginning and end of the target BGC. These arms must also match the ends of the linearized capture vector.

- Identify the exact boundaries of the target BGC (e.g.,

Preparation of the Targeting Cassette:

- Amplify the homology arms via PCR.

- If using a "capture" approach, assemble these arms onto a selectable marker cassette to create a linear "targeting cassette."

Red/ET Recombination in E. coli:

- Introduce the linearized capture vector and the targeting cassette (or the PCR-amplified BGC with homology arms) into the Red/ET-proficient E. coli strain (e.g., GBdir-red) via electroporation.

- Allow homologous recombination to occur, which results in the insertion of the target BGC into the capture vector, forming a circular, replicable plasmid.

Selection and Validation:

- Plate the transformation mixture on selective media to isolate clones containing the putative BGC plasmid.

- Screen colonies by colony PCR to confirm the presence of the BGC.

- Validate positive clones by restriction enzyme digestion and full-length sequencing of the plasmid insert to ensure fidelity and completeness.

Heterologous Expression:

- Introduce the validated plasmid containing the cloned BGC (e.g., pCAP-dmx) into a suitable Streptomyces heterologous host via protoplast transformation or conjugation.

- Culture the recombinant host under appropriate fermentation conditions.

Metabolite Analysis and Compound Discovery:

- Extract metabolites from the culture broth and mycelia.

- Analyze the extracts using Liquid Chromatography–High-Resolution Mass Spectrometry (LC-HRMS).

- Compare the metabolic profiles of the heterologous host containing the cloned BGC with a control strain (empty vector). New peaks present only in the experimental sample indicate compounds produced by the silent BGC, as demonstrated by the discovery of dmxorosin [4].

The experimental workflow from genome mining to novel compound discovery is summarized in the following diagram.

Integration with Computational and Analytical Workflows

Direct cloning does not operate in a vacuum; its success is heavily dependent on integrated bioinformatic and analytical pipelines.

- Genome Mining for BGC Prioritization: The initial identification of a target BGC relies on computational tools. Tools like antiSMASH (antibiotics & Secondary Metabolite Analysis Shell) are fundamental for the automated identification and annotation of BGCs in genomic data [1]. This allows researchers to survey an organism's biosynthetic potential and prioritize silent clusters for cloning based on novelty or predicted interesting features.

- The Role of Advanced Analytics: After heterologous expression, advanced metabolomics is critical. In the dmxorosin discovery, the Global Natural Products Social molecular networking platform and the COCONUT database were used to compare the MS data of the heterologous expresser against known compounds, allowing the researchers to confidently identify the produced compound as new [4]. This highlights the essential partnership between cloning and analytical chemistry.

Direct cloning has firmly established itself as an indispensable strategy in the modern natural product discovery pipeline. By providing a direct and robust route to capture, shuttle, and express silent biosynthetic gene clusters in tractable heterologous hosts, it effectively bypasses the regulatory constraints of native producers. This methodology is a key enabler for translating the immense genetic potential revealed by genome sequencing into tangible chemical entities. The continued refinement of direct cloning protocols—making them faster, more efficient, and applicable to ever-larger gene clusters—will undoubtedly accelerate the discovery of novel natural products. These compounds serve as crucial lead structures for the development of new pharmaceuticals, particularly in an era of rising antibiotic resistance. As such, direct cloning stands as a cornerstone technique for accessing the hidden biosynthetic diversity encoded within the microbial world.

The direct cloning of large biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) is a fundamental strategy in modern natural product research and drug discovery, enabling the heterologous expression and characterization of compounds from difficult-to-culture microorganisms [3]. However, this field faces three persistent technical challenges: the substantial size of many BGCs (often exceeding 100 kb), their frequent residence in GC-rich genomic regions, and their association with complex repetitive sequences [6] [7]. These characteristics complicate high-fidelity DNA extraction, precise enzymatic manipulation, and stable vector assembly. This Application Note details current, practical methodologies to overcome these hurdles, providing researchers with structured protocols and resource guides to accelerate the cloning of large, architecturally complex gene clusters.

Technical Hurdles and Strategic Solutions

The successful direct cloning of a BGC is contingent upon addressing its specific physicochemical and structural properties. The table below summarizes the primary challenges and the corresponding advanced strategies developed to counter them.

Table 1: Key Technical Hurdles and Corresponding Cloning Strategies

| Technical Hurdle | Underlying Cause of Difficulty | Recommended Strategy | Key Experimental Tools |

|---|---|---|---|

| Large Size (>50 kb) | Mechanical shearing during DNA isolation; low cloning efficiency in standard vectors [6]. | Preparation of High-Molecular-Weight (HMW) DNA; use of high-capacity vectors [6] [8]. | Cell embedding in agarose plugs; Cas9-guided excision (CISMR); Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs); Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) in yeast [6] [8]. |

| GC-Richness | Formation of stable secondary structures; impedes polymerase progression and restricts enzyme access [6]. | Optimization of PCR and enzymatic reaction buffers; use of specialized polymerases. | High-fidelity, GC-enhanced DNA polymerases (e.g., KAPA HiFi HotStart); additives like DMSO or betaine; optimized thermal cycling conditions [9] [10]. |

| Repetitive Sequences | Homologous recombination between repeats; misassembly during in vivo methods; incorrect sequence alignment [7]. | In vitro assembly methods; careful design of homology arms. | Gibson assembly; Golden Gate assembly; Red/ET Recombineering; designing unique homology arms for TAR cloning that flank, rather than reside within, repetitive regions [6] [7]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

The successful implementation of the strategies outlined in Table 1 relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table catalogues key solutions for direct cloning workflows.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Direct Cloning of Large Gene Clusters

| Research Reagent | Function / Application | Specific Example(s) / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| High-Capacity Vectors | Carrying large DNA inserts (50-200 kb) without instability [6]. | Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs), Cosmids (e.g., pWEB). |

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerases | Accurate amplification of long, GC-rich templates; critical for epPCR library construction with low bias [9] [10]. | KAPA HiFi HotStart, Platinum SuperFi II, Hot-Start Pfu DNA Polymerase. |

| CRISPR-Cas9 System | Programmable excision of specific, large DNA fragments from a genome [6]. | In vitro Cas9 nuclease with sgRNAs designed to flank a target BGC. |

| Homology Assembly Enzymes | In vitro assembly of multiple DNA fragments via homologous recombination. | Gibson Assembly Master Mix. |

| TAR "Capture" Vectors | In vivo homologous recombination in S. cerevisiae to assemble or capture large DNA regions [8]. | Yeast shuttle vectors with short homology arms targeting the gene cluster flanking sequences. |

| Viscoelastic Liquids & Capillary Systems | Highly sensitive separation and concentration of HMW DNA fragments [6]. | Used post-Cas9 cleavage to isolate specific fragments from a complex background. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: TAR-Mediated Reassembly of a Large BGC from Overlapping Cosmids

Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) is a powerful method for assembling a single, large DNA construct from multiple overlapping clones, such as those obtained from a cosmid library [8].

Workflow Overview:

Diagram 1: TAR cloning workflow from cosmids.

Materials:

- Overlapping cosmid clones spanning the target BGC.

- TAR "capture" vector (a yeast-E. coli shuttle vector with a selection marker).

- Saccharomyces cerevisiae host strain (e.g., VL6-48).

- Standard reagents for yeast transformation (PEG/LiAc, single-stranded carrier DNA).

- Selective media plates (e.g., lacking uracil for selection).

Method:

- Capture Vector Design: Linearize the TAR capture vector. The ends of the linearized vector must contain short homology arms (approximately 50-150 bp) that are identical to the 5' and 3' ends of the target BGC you wish to assemble. Crucially, these arms must be designed from unique, non-repetitive sequences that flank the gene cluster to avoid aberrant recombination within repetitive internal regions [8].

- Prepare DNA Mixture: Combine the linearized capture vector with a mixture of the overlapping cosmid clones. The cosmids should provide full coverage of the entire BGC with sufficient overlap between adjacent clones (typically >5 kb).

- Yeast Transformation: Co-transform the DNA mixture into competent S. cerevisiae cells using a high-efficiency protocol, such as the PEG/LiAc method.

- Selection and Growth: Plate the transformed yeast cells onto selective medium. The selection should be for the marker on the successfully recombined TAR vector. Incubate at 30°C for 2-3 days until colonies form.

- Validation: Isolate yeast plasmid DNA and transform it into a suitable E. coli host for amplification and downstream analysis. Confirm the integrity and correct assembly of the captured BGC using restriction fragment length polymorphism (RFLP) analysis and long-read sequencing (e.g., PacBio or Nanopore).

Protocol 2: High-Throughput Construction of Mutagenesis Libraries for BGC Optimization

Directed evolution through mutagenesis libraries is a key strategy for optimizing the expression and function of cloned BGCs in heterologous hosts. This protocol outlines a high-throughput, chip-based oligonucleotide synthesis approach for creating precise, high-coverage libraries [10].

Workflow Overview:

Diagram 2: Mutagenesis library construction workflow.

Materials:

- Target gene or BGC sequence.

- High-fidelity, low-bias DNA polymerase (e.g., KAPA HiFi HotStart, Platinum SuperFi II).

- Gibson Assembly Master Mix.

- Chip-synthesized oligonucleotide pool.

- Appropriate expression vector.

Method:

- Library Design: Divide the target gene sequence into tiled sub-libraries. For each amino acid position to be mutated, design oligonucleotides that contain the desired mutation (e.g., an amber codon, TAG) flanked by 16-19 bp homology arms for subsequent assembly [10].

- Oligonucleotide Synthesis: The designed oligonucleotide library is commercially synthesized using high-throughput, chip-based parallel synthesis technology.

- Sub-library Amplification: Use a high-fidelity DNA polymerase to PCR-amplify each sub-library from the pooled oligonucleotides. The use of a high-fidelity polymerase is critical to minimize the introduction of secondary, unintended mutations and to reduce the formation of chimeric sequences caused by incomplete extension [10].

- Assembly and Cloning: Assemble the full-length mutated gene from the amplified sub-libraries using Gibson assembly and clone it into the destination vector.

- Library Validation: Transform the assembled library into E. coli and use next-generation sequencing (NGS) to assess the mutation coverage and uniformity of the library. Aim for high coverage (>90%) and analyze unmapped reads to identify and troubleshoot issues like synthesis errors or PCR chimeras [10].

Concluding Remarks

The direct cloning of large, complex BGCs is no longer an insurmountable challenge. By leveraging a toolkit of specialized strategies—including TAR for assembly, CRISPR for precise excision, and optimized reagents for handling difficult sequences—researchers can systematically overcome the hurdles of size, GC-richness, and repetitive elements. The protocols detailed herein provide a actionable framework for accessing the vast untapped reservoir of natural products encoded in microbial genomes, thereby accelerating the discovery and development of novel therapeutic agents.

The field of molecular cloning has undergone a revolutionary transformation, shifting from traditional library-based approaches to sophisticated direct capture and editing technologies. This evolution is particularly crucial for research on large gene clusters, such as natural product biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), where conventional methods often proved slow and inefficient [3]. The limitations of native host-based approaches, including poor expression of silent BGCs under laboratory conditions, have driven the development of heterologous host-based genome mining strategies [3]. This application note examines the trajectory of cloning technology within the context of direct cloning strategies for large gene clusters, providing researchers with current methodologies and practical frameworks for implementation.

The Paradigm Shift: From Library-Based Cloning to Direct Capture

Historical Limitations of Library Approaches

Traditional genomic library construction and screening presented significant bottlenecks for cloning large gene clusters. These methods involved fragmenting genomic DNA, cloning into vectors, transforming hosts, and laboriously screening thousands to millions of clones—a process that could require weeks to months [11]. The fundamental challenge lay in the random nature of library construction, which often resulted in incomplete coverage or fragmentation of large gene clusters essential for natural product synthesis.

The Direct Capture Revolution

Direct cloning strategies emerged to address these limitations by enabling targeted isolation of specific genomic regions of interest without library construction and screening. As summarized in recent advances, each direct cloning method must resolve three critical issues: (1) genomic DNA preparation, (2) bilateral boundary digestion for target BGC release, and (3) BGC and capture vector assembly [3]. This paradigm shift has dramatically accelerated the cloning of large gene clusters, reducing the process from months to days in some cases [11].

Table 1: Comparison of Cloning Technology Generations

| Technology Generation | Key Methodology | Maximum Insert Size | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Genomic Libraries | Random fragmentation, library construction, and screening | 40-50 kb (cosmid); >100 kb (BAC) | Gene discovery, sequencing projects |

| Target Sequence Capture | Hybridization with RNA baits to genomic DNA | Dependent on bait design | Phylogenomics, variant discovery |

| Direct Cloning & Capture | PCR-independent capture using specific enzymes | >50 kb | Natural product BGC cloning |

| Programmable Chromosome Engineering | CRISPR-based and recombinase-based systems | Megabase scale | Chromosome engineering, crop improvement |

Modern Direct Capture Methodologies

CRISPR-Enhanced Retrieval Systems

The CRISPR Counter-Selection Interruption Circuit (CCIC) represents a significant advancement in clone retrieval from complex metagenomic libraries. This system utilizes nuclease-deficient Cas9 (dCas9) programmed with guide RNAs to target unique barcode sequences adjacent to cloned inserts, enabling selective survival under counter-selection conditions [11].

Experimental Protocol: CCIC-Based Clone Retrieval

Vector Design: Engineer a cloning vector (e.g., pCCIC cosmid) containing:

- A counter-selection marker (e.g., sacB gene for sucrose sensitivity)

- A promoter driving counter-selection gene expression

- A degenerate 24-bp barcode sequence between promoter and counter-selection gene

- Multiple cloning site for insert DNA

Library Construction:

- Fragment high-molecular-weight metagenomic DNA

- Ligate into barcoded pCCIC vectors

- Package using lambda phage and transform into E. coli

- Pool transformants to create library

Library Sequencing & Indexing:

- Sequence library pool using PacBio HiFi long-read technology

- Link barcode sequences to specific cloned inserts bioinformatically

- Identify target clones based on insert sequence

Target Retrieval:

- Design sgRNA targeting barcode of desired clone

- Introduce sgRNA plasmid into library pool

- Plate on sucrose-containing media

- Only clones with dCas9-silenced sacB expression survive

This method has demonstrated efficiency in retrieving target sequences from pools containing up to 50,000 non-target clones with positive hit rates exceeding 70% [11].

Programmable Chromosome Engineering

A groundbreaking advancement in large-scale DNA manipulation comes from Programmable Chromosome Engineering (PCE) systems, which enable precise editing of chromosomal segments ranging from kilobases to megabases [12] [13]. This technology overcomes historical limitations of the Cre-Lox system through three key innovations:

- Asymmetric Lox Site Design: Reduces reversible recombination activity by over 10-fold while maintaining high-efficiency forward recombination [12]

- AiCErec Recombinase Engineering: Uses AI-informed protein engineering to optimize Cre's multimerization interface, yielding a variant with 3.5 times higher recombination efficiency than wild-type [12]

- Scarless Editing Strategy: Employs prime editors with specifically designed Re-pegRNAs to replace residual Lox sites with original genomic sequence [12]

Experimental Protocol: PCE for Large-Scale Genome Engineering

Target Selection: Identify target genomic region (demonstrated for manipulations up to 12 Mb inversions and 4 Mb deletions) [13]

gRNA Design:

- Design asymmetric Lox sites flanking target region

- Create Re-pegRNAs for precise editing outcomes

System Delivery:

- Deliver PCE components (engineered Cre recombinase, asymmetric Lox sites, Re-pegRNAs) to plant or animal cells

- Use appropriate transformation method for target cell type

Selection & Validation:

- Apply appropriate selection for edited cells

- Validate edits via PCR, sequencing, and phenotypic assessment

- Confirm precise boundaries and absence of residual sequences

In proof-of-concept applications, researchers used PCE technology to create herbicide-resistant rice germplasm through a precise 315-kb chromosomal inversion [12].

Table 2: Capabilities of Programmable Chromosome Engineering Systems

| Edit Type | Demonstrated Scale | Experimental System | Key Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeted Insertion | 18.8 kb | Plant and animal cells | Gene stacking |

| Sequence Replacement | 5 kb | Plant and animal cells | Allele swapping |

| Chromosomal Inversion | 12 Mb | Plant and animal cells | Gene regulation studies |

| Chromosomal Deletion | 4 Mb | Plant and animal cells | Functional genomics |

| Whole Chromosome Translocation | Entire chromosomes | Plant and animal cells | Chromosome engineering |

| Precise Inversion | 315 kb | Rice | Herbicide-resistant crops |

Application-Focused Workflows

Optimized Gene Cloning in Complex Genomes

Recent work on cloning disease resistance genes in wheat demonstrates an optimized workflow that combines multiple advanced techniques for rapid gene identification [14]. This approach successfully cloned the stem rust resistance gene Sr6 in just 179 days using only three square meters of plant growth space [14].

Experimental Protocol: High-Throughput Gene Cloning in Wheat

Mutagenesis Population:

- Treat wheat seeds with ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS)

- Sow M1 generation at high density (15 grains per 64 cm²)

- Harvest individual M2 spikes as separate families

Phenotypic Screening:

- Inoculate 3-week-old M2 seedlings with pathogen (Puccinia graminis)

- Identify loss-of-resistance mutants based on sporulation

- Transfer putative mutants to single pots and re-inoculate

Genomic Analysis:

- Harvest leaf tissue from confirmed mutants for RNA sequencing

- Generate isoform sequencing (Iso-Seq) data for wild-type parent

- Perform MutIsoSeq analysis to identify transcripts with EMS-type mutations

Validation:

- Amplify and sequence candidate gene from all mutants

- Develop KASP marker for genotyping

- Confirm gene identity via VIGS and CRISPR/Cas9 knockout

This workflow successfully identified Sr6 as encoding a CC-BED-domain-containing NLR immune receptor, with mutations found in 97 of 98 loss-of-function mutants [14].

Target Sequence Capture for Phylogenomics

For evolutionary studies, target sequence capture remains a powerful method when combined with appropriate bait design strategies [15]. This approach uses custom RNA baits to hybridize with and enrich complementary DNA regions before sequencing.

Experimental Protocol: Phylogenomic Target Capture

Bait Selection:

- Identify conserved loci across taxonomic group of interest

- Use existing bait sets (e.g., UCEs, AHE) or design custom baits

- Consider genetic divergence between bait source and study organisms

Library Preparation & Capture:

- Extract high-quality genomic DNA

- Fragment DNA and prepare sequencing libraries

- Hybridize with biotinylated RNA baits

- Capture bait-bound fragments using streptavidin beads

Sequencing & Analysis:

- Sequence captured libraries on appropriate platform

- Process data with phylogenetically-informed bioinformatic pipelines

This method is particularly valuable for degraded DNA samples from museum specimens, as the enrichment provides greater coverage of target loci [15].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for Direct Cloning Applications

| Reagent/Resource | Function | Application Examples |

|---|---|---|

| dCas9 (nuclease-deficient) | Sequence-specific binding without cleavage | CCIC clone retrieval [11] |

| Asymmetric Lox Sites | Directional recombination with reduced reversibility | PCE systems [12] |

| Engineered Cre Recombinase (AiCErec) | High-efficiency recombination | Large DNA fragment manipulation [12] |

| Re-pegRNAs | Guide prime editors for scarless editing | Residual site removal in PCE [12] |

| Barcoded CCIC Vectors | Clone-specific identification and retrieval | Metagenomic library screening [11] |

| EMS (Ethyl Methanesulfonate) | Chemical mutagenesis to induce point mutations | Forward genetic screens [14] |

| Target Capture Baits | Hybridization-based enrichment of genomic regions | Phylogenomic studies [15] |

| Tapestri Technology | Single-cell DNA-RNA sequencing platform | Functional phenotyping of variants [16] |

The trajectory from genomic libraries to direct capture technologies represents a fundamental shift in how researchers approach gene cloning and manipulation. Modern methods now enable precise programming of cellular machinery to target, capture, and engineer genetic elements with unprecedented efficiency and scale. These advances are particularly transformative for the study of large gene clusters, where traditional methods often failed. As direct cloning strategies continue to evolve, they promise to further accelerate natural product discovery, crop improvement, and our fundamental understanding of genetic regulation.

The Critical Need for Large-Insert Cloning in Natural Product Discovery and Functional Genomics

The rapid accumulation of genomic data has revealed a vast reservoir of uncharacterized biosynthetic potential, particularly in the genomes of uncultured microorganisms. Large-insert cloning technologies serve as the critical bridge connecting this genetic potential to discoverable natural products and functional insights. These methods enable researchers to directly capture, manipulate, and express large genomic fragments that are often beyond the capacity of conventional cloning vectors. In the context of functional genomics, large-insert cloning facilitates the systematic study of gene function by allowing researchers to transfer entire gene clusters into model organisms for phenotypic analysis [17]. Similarly, in natural product discovery, these techniques provide access to extensive biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) encoding novel compounds with potential therapeutic value [8] [3]. This application note details the experimental frameworks and reagent solutions essential for successful large-insert cloning, emphasizing its transformative role in direct cloning strategies for large gene cluster research.

The Scientific Challenge: Why Large-Insert Cloning is Necessary

The Scale of Biological Complexity

Many biological functions are encoded not by single genes but by large, coordinated genetic elements. Biosynthetic gene clusters for natural products often span 30-150 kilobases, encompassing genes for biosynthesis, regulation, and transport [8] [3]. Similarly, functional studies of gene regulatory elements or multi-gene complexes require capturing large genomic contexts to preserve biological activity. Conventional plasmid vectors typically accommodate only 2-3kb inserts, creating a fundamental technical gap in studying these complex genetic systems [18].

The Problem of Uncultured Microbes

Single gram of soil can contain thousands of unique bacterial species, most of which have never been cultured in laboratory settings [8]. This represents one of biology's largest reservoirs of unexplored genetic diversity and natural product potential. Large-insert cloning from environmental DNA (eDNA) allows researchers to access this uncultured majority by capturing their genetic material directly from environmental samples and expressing it in tractable host organisms [8].

Table 1: Comparison of Cloning Vectors by Insert Capacity

| Vector Type | Typical Insert Size | Primary Applications | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plasmid | 2-3 kb | Gene expression, protein production | High copy number; easy manipulation |

| Cosmid | 30-45 kb | Small gene clusters, metagenomic libraries | Efficient packaging and transduction |

| Bacterial Artificial Chromosome (BAC) | Up to 350 kb | Large gene clusters, genomic libraries | Very large insert capacity; stable maintenance |

| Yeast Artificial Chromosome (YAC) | Up to 1,000 kb | Extremely large gene clusters, synthetic biology | Largest capacity; eukaryotic features |

Quantitative Foundations: Understanding Library Scale Requirements

The probability of capturing any specific large gene cluster from a complex environmental sample depends on both the insert size of the cloning vector and the overall size of the library. Research with soil-derived eDNA cosmid libraries has empirically demonstrated that library complexity must be substantial to ensure complete coverage of large biosynthetic pathways [8].

Table 2: Empirical Library Size Requirements for Soil eDNA Studies

| Library Source | Library Size | Insert Size (Cosmid) | Theoretical Coverage | Practical Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Utah Soil Library | ~10 million clones | 30-40 kb | Extensive but incomplete for large BGCs | Enabled identification of overlapping clones for reassembly |

| California Soil Library | ~15 million clones | 30-40 kb | More comprehensive coverage | Facilitated recovery of complete pathways via overlapping clones |

These studies revealed that while constructing 30-40kb insert cosmid libraries from environmental samples is now routine, capturing BGCs larger than a single cosmid insert requires either extremely large libraries or strategies to reassemble complete pathways from multiple overlapping clones [8]. This fundamental limitation has driven the development of specialized methods for cloning large genomic fragments in the 50-150kb range [19].

Experimental Framework: TAR-Mediated Reassembly of Large Gene Clusters

Transformation-associated recombination (TAR) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae provides a powerful method for reassembling large natural product biosynthetic gene clusters from collections of overlapping eDNA cosmid clones. This approach leverages the highly efficient homologous recombination system of yeast to assemble large DNA constructs that are challenging to manipulate using traditional restriction enzyme-based methods [8].

Protocol: TAR Reassembly of Large BGCs from Overlapping Cosmid Clones

Step 1: Library Construction and Screening

- High Molecular Weight DNA Extraction: Extract DNA directly from environmental samples (e.g., soil) using gentle lysis buffer (2% SDS, 100 mM Tris-HCl, 100 mM EDTA, 1.5 M NaCl, 1% CTAB). Incubate at 70°C for 2 hours, then remove particulates by centrifugation at 4,000 × g for 30 minutes [8].

- DNA Purification and Size Selection: Precipitate DNA with isopropyl alcohol, then perform gel electrophoresis (1% agarose, 16h, 20V) to isolate high molecular weight DNA (>40 kb) [8].

- Cosmid Library Construction: Blunt-end the purified DNA, ligate into cosmid vectors (e.g., pWEB or pWEB-TNC), package into lambda phage, and transduce into E. coli host cells (e.g., EC100) [8].

- Library Formatting and Screening: Create glycerol stocks and DNA minipreps arrayed in 8×8 grids representing 250,000-320,000 clones. Pool rows and columns for efficient PCR-based screening using degenerate primers targeting conserved biosynthetic genes (e.g., β-ketoacyl synthase sequences for Type II PKS systems) [8].

Step 2: Identification of Overlapping Clones

- PCR Screening: Use degenerate primers to identify cosmids containing portions of the target BGC:

- For β-ketoacyl synthase domains: dp:KSβ (5′-TTCGGSGGNTTCCAGWSNGCSATG-3′) and dp:ACP (5′-TCSAKSAGSGCSANSGASTCGTANCC-3′) [8].

- PCR conditions: 50 ng eDNA template, 2.5 μM each primer, 2 mM dNTPs, ThermoPol Buffer, 0.5 U Taq polymerase, 5% DMSO.

- Touchdown protocol: Initial denaturation (95°C, 2 min); 8 touchdown cycles (95°C/45s, 65°C→58°C/1min, 72°C/2min); 35 standard cycles (95°C/45s, 58°C/1min, 72°C/2min); final extension (72°C, 2 min) [8].

- Clone Verification: Sequence amplicons of correct size (~1.5 kb for Type II PKS) to confirm identity and identify overlapping cosmids for reassembly [8].

Step 3: TAR Assembly

- Capture Vector Design: Construct a TAR "capture" vector containing:

- Yeast replication origin (ARS/CEN)

- Yeast selectable marker (e.g., URA3)

- Homology arms (500-1000 bp) matching the 5' and 3' ends of the target BGC

- Co-transformation: Combine the capture vector with overlapping cosmid clones (typically 2-4 clones spanning the entire BGC) and transform into S. cerevisiae using standard yeast transformation protocols [8].

- Selection and Verification: Select for yeast transformants containing the reassembled BGC using appropriate selection media. Verify correct assembly by PCR and restriction mapping [8].

Figure 1: TAR-mediated reassembly workflow for large biosynthetic gene clusters from overlapping cosmid clones.

Direct Cloning Strategies for Large Genomic Fragments

Recent advances in direct cloning methods have expanded capabilities for capturing large genomic fragments (50-150 kb) without the need for library construction and screening. These approaches address the three fundamental challenges of large fragment cloning: genomic DNA preparation, precise bilateral boundary digestion for target release, and efficient assembly with capture vectors [3].

Methodological Approaches for Direct Cloning

Vector Systems for Large-Insert Cloning

- Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs): Capable of maintaining inserts up to 350 kb, though typically yielding metagenomic libraries 2-3 orders of magnitude smaller than cosmid-based libraries [8].

- Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR): Enables targeted capture of specific large genomic regions using homology arms, bypassing library construction [8].

- Advanced Direct Cloning Methods: Newer techniques including:

- Cas9-assisted targeting of chromosome segments (CATS)

- Metagenomic direct cloning approaches [19]

Critical Considerations for Direct Cloning

- DNA Quality and Integrity: Isolate high molecular weight DNA with minimal shearing using gentle extraction methods [8] [3].

- Boundary Determination: Precisely identify the 5' and 3' boundaries of target gene clusters through bioinformatic analysis prior to cloning [3].

- Vector-Host Compatibility: Select appropriate vector-host systems that support stable maintenance of large inserts without rearrangement [8] [18].

Figure 2: Decision framework for selecting appropriate large-insert cloning strategies based on project requirements.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Successful implementation of large-insert cloning strategies requires specialized reagents and systems optimized for handling high molecular weight DNA and maintaining large constructs.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Large-Insert Cloning

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in Large-Insert Cloning | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cloning Vectors | pWEB, pWEB-TNC cosmids; BAC vectors; TAR capture vectors | Provide backbone for insert propagation and selection | Stability with large inserts; appropriate origin of replication; selectable markers |

| Host Systems | E. coli EC100 (cosmid); S. cerevisiae (TAR); BAC-compatible E. coli | Enable replication and maintenance of large inserts | Recombination deficiency (recA-); restriction modification systems; transformation efficiency |

| Enzymes for DNA Manipulation | End-It Blunt-Ending Kit; T4 DNA Ligase; High-Fidelity Restriction Enzymes | Modify DNA ends for cloning; ligate fragments | Minimal shearing activity; high efficiency with large fragments; methylation sensitivity |

| DNA Purification Systems | Gel electrophoresis; Silica column purification; SPRI beads | Size selection and purification of large DNA fragments | Gentle handling to prevent shearing; efficient recovery of high molecular weight DNA |

| Screening Tools | Degenerate primers for BGC detection; antibiotic resistance markers; blue/white screening | Identification of correct clones and assemblies | Specificity for target sequences; minimal background; visual differentiation |

Applications and Future Perspectives

Large-insert cloning technologies are driving advances in two primary domains: functional genomics and natural product discovery. In functional genomics, CRISPR-based functional genomics tools enable high-throughput screening of gene function in vertebrate models, with large-insert cloning providing the means to transfer entire gene regulatory elements or multi-gene complexes into model organisms [17]. For natural product discovery, these methods facilitate the cloning and heterologous expression of large biosynthetic gene clusters from uncultured microorganisms, providing access to novel chemical entities [8] [3].

The future of large-insert cloning will likely see continued development of more efficient direct cloning methods, improved vector systems for even larger inserts, and integration with synthetic biology approaches for refactoring and optimizing cloned gene clusters. As these technologies mature, they will further accelerate the connection between genomic sequence and biological function, enabling researchers to fully explore the functional potential of complex genomes.

A Methodological Deep Dive: From RecE/RecT to CRISPR-Cas12a for Capturing BGCs

The expanding field of natural product discovery and synthetic biology necessitates the precise cloning and manipulation of large biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), which often range from 10 kb to over 200 kb in size [20]. These clusters encode the machinery for producing diverse compounds with biological activities, including antibiotics and anticancer agents. Traditional cloning methods, which rely on restriction enzymes and ligation, are often inadequate for capturing these large DNA sequences due to their limited cloning capacity, dependency on suitable restriction sites, and low efficiency [21]. Functional analysis of the genome sequences being delivered by massively parallel sequencing requires more efficient cloning methods [22].

Transformation-associated recombination (TAR) in Saccharomyces cerevisiae represents one alternative, but its efficiency is relatively low (0.1–2%) due to vector recircularisation by non-homologous end joining (NHEJ), necessitating intensive screening [20]. Escherichia coli–Streptomyces shuttle bacterial artificial chromosomal (BAC) vectors can carry large-sized BGCs, but the construction of BAC libraries is laborious, expensive, and results in cloning of random genome parts rather than a specific BGC of interest [20]. Against this backdrop, recombineering (recombination-mediated genetic engineering) has emerged as a powerful approach, with the RecE/RecT system from the Rac prophage demonstrating particular efficacy for the direct cloning of large genomic sequences [22] [23].

Mechanistic Basis of the RecE/RecT System

System Components and Functional Relationship

The RecE/RecT system constitutes a dedicated homologous recombination pathway encoded by the Rac prophage in E. coli. This system functions independently of the native RecA/RecBCD pathway and comprises two essential proteins that operate as an orthologous pair, meaning recombination proceeds efficiently only when both components from the same origin are co-expressed [24].

- RecE: A potent 5'→3' exonuclease that processes double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) ends. It resects one strand of the DNA, generating 3'-ended single-stranded DNA (ssDNA) overhangs [24] [23].

- RecT: A single-stranded DNA annealing protein (SSAP) that binds to the ssDNA overhangs generated by RecE. RecT facilitates the annealing of this single-stranded DNA to complementary sequences, promoting strand invasion or annealing [24] [23].

The functional synergy between these proteins is critical. Neither RecE nor RecT alone can mediate efficient recombination, and they cannot be functionally substituted by their lambda phage orthologs (Redα/Redβ) or by the host RecA protein [24]. This specificity is attributed to a required protein-protein interaction between the two components of an orthologous pair [24].

The following diagram illustrates the functional relationship and process of double-stranded break repair mediated by the RecE/RecT system:

Comparative Analysis of Recombineering Systems

Different recombineering systems exhibit distinct functional characteristics and operational requirements. The table below provides a comparative overview of the RecE/RecT system alongside other prominent systems:

Table 1: Comparison of Key Recombineering Systems

| System | Origin | Core Components | Key Mechanism | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| RecE/RecT | Rac prophage | RecE (exonuclease), RecT (SSAP) | Linear-linear homologous recombination | Highly efficient for large fragment cloning (>50 kb); requires full-length RecE for optimal activity [22] [23] |

| Redα/Redβ (Lambda Red) | Lambda phage | Redα (exonuclease), Redβ (SSAP) | Homologous recombination initiated at dsDNA breaks | Functionally similar but mechanistically distinct from RecE/RecT; orthologous pairing required [24] |

| SSAP-only strategies | Various phages | Beta protein (from Lambda Red) | Annealing of ssDNA to replication fork | Can function without exonuclease partner; used to enhance CRISPR editing efficiency [25] |

| CRISPR-Cas9/Beta | Hybrid system | Cas9 (nuclease), Beta (SSAP) | DSB creation followed by SSAP-mediated repair | Provides selective pressure via DSB lethality; improved editing efficiency with Beta [25] |

A key advancement in this field was the discovery that the full-length RecE protein significantly enhances the efficiency of linear-linear homologous recombination compared to the truncated versions previously studied [22]. This full-length RecE facilitates the direct cloning of large genomic sequences, including megasynthetase gene clusters ranging from 10–52 kb, enabling bioprospecting for natural products [22].

Application Notes: Experimental Protocol for Direct Cloning

This section provides a detailed methodology for implementing RecE/RecT recombineering for direct cloning of large genomic fragments, such as biosynthetic gene clusters.

The complete experimental process, from target identification to heterologous expression, involves multiple stages as illustrated below:

Detailed Stepwise Protocol

Step 1: Target Identification and Hook Design

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify the target BGC and its flanking sequences from genomic data.

- Homology Hook Design: Design 50-base pair homology arms (hooks) complementary to the regions immediately flanking the target BGC. These hooks will be incorporated into the linear vector backbone [20].

Step 2: Vector Preparation

- Vector Linearization: Prepare a linearized vector backbone (e.g., a yeast-E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vector) containing the necessary elements for selection and maintenance in various hosts.

- Homology Arm Incorporation: Incorporate the designed homology hooks at both ends of the linearized vector using PCR amplification or enzymatic assembly [20].

Step 3: Genomic DNA Isolation

- High-Molecular-Weight DNA Extraction: Isolate intact, high-quality genomic DNA from the source organism using methods that preserve large DNA fragments (e.g., agarose plug embedding or gentle phenol-chloroform extraction).

Step 4: Co-transformation with RecE/RecT

- RecE/RecT Expression: Use a host strain (e.g., E. coli GB2005) that expresses the full-length RecE and RecT proteins. Alternatively, co-transform with a plasmid expressing these genes under inducible promoters [22].

- Transformation Mixture: Co-transform the linear vector (50-100 ng) and genomic DNA (200-500 ng) into the recombinase-expressing host via electroporation [20] [22].

Step 5: Recombinant Selection

- Selective Plating: Plate transformation mixtures onto selective media containing appropriate antibiotics.

- Screening: Screen resulting colonies for correct recombinants using:

- PCR screening across cloning junctions

- Restriction analysis

- Comparative genome hybridization

- Counter-Selection: Implement counterselection markers (e.g., yeast killer toxin K1 cassette, URA3 with 5-FOA) to reduce background from empty vectors [20].

Step 6: Heterologous Expression

- Vector Isolation: Isate the recombinant vector containing the captured BGC.

- Host Transformation: Introduce the construct into a suitable heterologous host (e.g., Streptomyces albus Del14) for expression.

- Product Analysis: Screen for the production of expected compounds using metabolomic approaches (e.g., LC-MS) [20].

Critical Parameters for Success

- Homology Arm Length: Optimal homology arm length is approximately 50 base pairs for efficient recombination [24]. While shorter arms (35-40 bp) can function, efficiency decreases significantly.

- Protein Expression Balance: Recombination efficiency correlates with the stoichiometric balance between RecE and RecT, with a slight excess of the annealing protein (RecT) being beneficial [24].

- DNA Substrate Quality: Use high-quality, undegraded genomic DNA as substrate to maximize the yield of full-length clones.

- Host Strain Selection: Use recombination-proficient strains such as E. coli GB2005 or WM6026 (for conjugation), or engineering strains to express the RecE/RecT system [20] [22].

Performance Data and Applications

Quantitative Performance Metrics

The RecE/RecT system has demonstrated remarkable efficiency in cloning large genomic fragments, as summarized in the table below:

Table 2: Performance Metrics of RecE/RecT-Mediated Direct Cloning

| Application | Insert Size | Efficiency | Key Outcome |

|---|---|---|---|

| Megasynthetase clusters from Photorhabdus luminescens | 10-52 kb | Highly efficient | Successful cloning of all 10 targeted clusters; heterologous expression yielded luminmycin A and luminmide A/B [22] |

| Chelocardin BGC from Amycolatopsis sulphurea | 35 kb | Functional cloning | Successful heterologous expression in S. albus Del14 resulted in antibiotic production [20] |

| Daptomycin BGC from Streptomyces filamentosus | 67 kb | Functional cloning | Heterologous expression generated the corresponding antibiotic [20] |

| cDNA and BAC segment cloning | Variable | High efficiency | Precise cloning of exactly defined DNA segments [22] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for RecE/RecT Recombineering

| Reagent / Material | Function / Purpose | Examples / Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Full-length RecE/RecT expression system | Mediates homologous recombination between linear DNA fragments | Codon-optimized versions for enhanced expression in desired hosts [22] |

| Shuttle vectors | Cloning and maintenance of large inserts in multiple hosts | Yeast-E. coli-Streptomyces shuttle vectors (e.g., pCAP01, pTARa) [20] |

| High-efficiency competent cells | Transformation of large constructs | E. coli GB2005, E. coli WM6026 (for conjugation), S. cerevisiae BY4742 ΔKu80 (for TAR) [20] |

| Counterselectable markers | Elimination of empty vectors | Yeast killer toxin K1 cassette, URA3 with 5-FOA, sacB for negative selection in bacteria [20] |

| Homology hooks | Target-specific sequence recognition | 50 bp sequences homologous to regions flanking the target BGC [20] |

| High-fidelity DNA polymerase | Accurate amplification of vector backbones and homology arms | Phusion Hot Start II High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase [21] |

The RecE/RecT recombineering system represents a powerful and efficient methodology for the direct cloning of large genomic sequences, particularly biosynthetic gene clusters. Its ability to facilitate linear-linear homologous recombination enables the capture of gene clusters exceeding 50 kb with high fidelity, overcoming the limitations of traditional restriction enzyme-based cloning. The discovery that full-length RecE dramatically enhances this process has been instrumental in advancing bioprospecting efforts [22].

Future developments in this field are likely to focus on several key areas. First, the systematic discovery of novel recombinases from microbial sequencing data will expand the toolbox available for genome engineering [26]. Second, the integration of recombineering with other advanced technologies, such as CRISPR-Cas systems, will further enhance editing efficiency and specificity [25]. Finally, the continued optimization of delivery systems and host strains will broaden the application of these techniques across diverse bacterial species, including non-model organisms and pathogens.

As the field of synthetic biology continues to advance, the RecE/RecT system and related recombineering technologies will play an increasingly vital role in accessing and harnessing the vast genetic diversity encoded in microbial genomes for drug discovery, bioengineering, and fundamental biological research.

Direct cloning of large biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) is a fundamental challenge in natural product discovery and synthetic biology. Microorganisms, particularly actinobacteria, represent an unrivalled source of bioactive small molecules, with many clinically used compounds deriving directly from these natural products [27]. However, genome sequencing has revealed that the vast majority of BGCs are cryptic, meaning they are not expressed under standard laboratory conditions [27]. Furthermore, more than 10% of characterized BGCs exceed 80 kb in size, with 40% having GC content greater than 70% [27]. This combination of large size and high GC content makes these clusters particularly difficult to clone and express using conventional methods.

The emergence of CRISPR-based technologies has revolutionized large-fragment cloning by enabling precise targeting and efficient capture of specific genomic regions. Within this context, this Application Note focuses on CRISPR-enhanced capture methods, specifically CAT-FISHING (CRISPR/Cas12a-mediated fast direct biosynthetic gene cluster cloning) and related approaches, for isolating superlarge BGCs exceeding 100 kb. These technologies address critical limitations of earlier methods by combining programmable nucleases with advanced recombination systems, opening new avenues for natural product-based drug discovery [27] [28].

Core Principles of CRISPR-Enhanced Capture

CRISPR-enhanced BGC cloning methods leverage the programmability of CRISPR nucleases to create precise double-strand breaks at flanking regions of target clusters. The fundamental process involves two indispensable steps: targeted release of the large genomic fragment and its subsequent capture into an appropriate vector system [28]. CAT-FISHING specifically utilizes Cas12a (Cpf1), which offers distinct advantages over other CRISPR nucleases, including recognition of T-rich PAM sites and generation of staggered ends with 4-5 nt overhangs that facilitate subsequent assembly steps [27].

The technology combines Cas12a cleavage with advanced features of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library construction, creating a robust platform for capturing large BGCs with high GC content [27]. This synergy addresses a significant challenge in the field, as traditional BAC library construction, while suitable for large DNA fragments with high GC content, is notoriously time-consuming, labor-intensive, and technically demanding [27].

Comparative Analysis of Large-Fragment Cloning Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Major Large-Fragment Cloning Methods

| Method | Key Features | Maximum Clone Size | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CAT-FISHING | Combines Cas12a cleavage with BAC features | 145 kb (demonstrated) [27] | Handles high GC content (>70%); high efficiency | Specialized vector construction required |

| CRISPR-Cas9/Gibson Assembly | Uses Cas9 for cleavage with Gibson Assembly | 77 kb (demonstrated) [29] | Simpler vector construction; high fidelity for <50 kb fragments | Requires agarose gel embedding technique [29] |

| TAR | Based on homologous recombination in yeast | Varies | Efficient for some fragment types | Challenging plasmid extraction from yeast; complex restriction analysis [29] |

| ExoCET | Integrates in vitro annealing with in vivo recombination in E. coli | >150 kb (reported) [28] | Does not require restriction sites | Limited by restriction sites for BGC acquisition [29] |

| CATCH | Cas9-assisted targeting of chromosome segments | Varies | Not restricted by restriction sites | Uses agarose gel embedding technique [29] |

Experimental Protocols

CAT-FISHING Workflow for Large BGC Capture

3.1.1 Capture Plasmid Construction The capture plasmid is constructed by introducing the lacZ gene and two PCR-amplified homology arms (each ≥30 bp containing at least one PAM site) corresponding to the flanking regions of the target BGC into the pBAC2015 vector [27].

- Procedure:

- Mix 100 ng of amplified pBAC2015 backbone, 50 ng of each homology arm DNA, and 50 ng of lacZ cassette DNA

- Add 2 μL buffer and 2 μL recombinase (EZmax one-step seamless cloning kit)

- Incubate at 37°C for 30 minutes

- Use mixture directly for transformation [27]

Alternatively, if homology arms contain only one PAM site, two 30-bp arms (4-nt PAM site + 26-nt target recognition sequence) can be used. The linearized capture plasmid can be obtained by one-step PCR with homology arm-incorporated primers using pBAC2015 as template [27].

3.1.2 Genomic DNA Preparation High-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA is essential for success. For actinomycetes:

- Culture strain in TSB medium supplemented with glycine (5 g/L) or sucrose (10.3%) at 30°C for 24-48 hours

- Collect mycelium by centrifugation (4°C, 4000 × g, 5 minutes)

- Resuspend in TE25S buffer (25 mM Tris-HCl, 25 mM EDTA, 0.3 M sucrose, pH 8)

- Adjust mycelium density to OD₆₀₀ of 1.9-2.0 with TE25S

- Mix with equal volume of 1.0% LMP agarose at 50°C

- Pour into plug mold and solidify

- Incubate blocks at 37°C for 1 hour in lysozyme solution (2 mg/mL in TE25S)

- Replace with proteinase K solution (1 mg/mL in NDS) and incubate at 50°C for 2 hours

- Wash blocks with TE buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl, 1 mM EDTA, pH 8) [27]

3.1.3 Cas12a Cleavage and Fragment Capture The critical step involves Cas12a-mediated release of the target fragment and its homologous recombination with the capture plasmid.

Figure 1: CAT-FISHING Workflow for BGC Capture

CRISPR-Cas9/Gibson Assembly Method

3.2.1 sgRNA Synthesis and Purification

- Design 20 bp oligonucleotides using available resources (e.g., Zhang lab design tool)

- Obtain double-stranded transcription template DNA by PCR annealing

- Perform in vitro transcription using T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit

- Purify RNA using VAHTS RNA Clean Beads [29]

3.2.2 Cas9 Expression and Purification

- Clone Cas9 gene fragments into pET28a vector with SalI and NcoI restriction sites

- Transform into E. coli BL21(DE3)

- Grow in LB medium at 37°C until OD₆₀₀ reaches 0.6-0.8

- Induce with 0.4 mM IPTG at 16°C for 20 hours

- Purify recombinant protein using AKTA system [29]

3.2.3 In Vitro Cas9 Cleavage of Genomic DNA

- Reaction Setup:

- 800 nM Cas9

- 400 nM sgRNA1 + 400 nM sgRNA2

- 30 μL 10× NEB buffer 3.1

- 1 μL recombinant ribonuclease inhibitor

- Total volume: 300 μL (without genomic DNA)

- Incubate at 37°C for 20 minutes

- Add 0.02-0.04 nM genomic DNA

- Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours [29]

3.2.4 DNA Purification and Gibson Assembly

- Add equal volume phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol to cleavage reaction

- Centrifuge and collect supernatant

- Add 3M sodium acetate to supernatant

- Precipitate with ethanol

- Perform Gibson assembly with purified fragments and vector [29]

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents for CRISPR-Enhanced BGC Capture

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application Notes |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Nucleases | Cas12a (Cpf1), Cas9 | Programmable DNA cleavage; Cas12a preferred for staggered ends and T-rich PAM sites [27] |

| Vector Systems | pBAC2015, Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes | Stable maintenance of large inserts; essential for >100 kb fragments [27] |

| Host Strains | E. coli derivatives, Streptomyces albus J1074 (heterologous expression) | E. coli for cloning; specialized Streptomyces strains for expression of actinobacterial BGCs [27] |

| Enzyme Kits | EZmax one-step seamless cloning kit, T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit, Gibson Assembly mix | Streamline key steps including assembly, in vitro transcription, and recombination [27] [29] |

| Selection Markers | lacZ (blue/white screening), antibiotic resistance genes | Enable selection of successful recombinants and maintain vector stability [27] |

| Culture Media | Luria-Bertani, Soybean flour-mannitol, TSB with glycine/sucrose | Optimized growth conditions for source organisms and heterologous hosts [27] |

Application Case Study: Marinolactam A Discovery

The power of CAT-FISHING is exemplified by the discovery of marinolactam A, a novel macrolactam compound with promising anticancer activity. Researchers successfully captured a 110 kb cryptic polyketide encoding BGC from Micromonospora sp. 181 and heterologously expressed it in a Streptomyces albus J1074-derived cluster-free chassis strain [27]. This breakthrough demonstrates the practical utility of CRISPR-enhanced capture for unlocking silent biosynthetic potential.

The process involved:

- Identification of the cryptic BGC through bioinformatic analysis

- Precise targeting and capture using CAT-FISHING methodology

- Heterologous expression in a optimized Streptomyces chassis

- Compound isolation and structure elucidation

- Bioactivity testing revealing anticancer properties [27]

This case study validates CAT-FISHING as a powerful method for complicated BGC cloning and highlights its importance to the entire community of natural product-based drug discovery [27].

Technical Considerations and Optimization

Critical Parameters for Success

Homology Arm Design: Arms should be ≥30 bp with at least one PAM site. Optimal GC content and length improve recombination efficiency. For difficult regions, consider extending arm length to 50-100 bp [27].

GC-Rich Content Challenges: BGCs from actinobacteria often have >70% GC content. Optimize hybridization temperatures and use betaine or similar additives in PCR and recombination reactions to mitigate challenges.

Fragment Size Limitations: While CAT-FISHING has captured fragments up to 145 kb, efficiency decreases with increasing size. For fragments >100 kb, optimize Cas12a cleavage time and use high-efficiency electrocompetent cells for transformation.

Troubleshooting Common Issues

- Low Capture Efficiency: Verify Cas12a activity with control substrates, ensure high-quality genomic DNA preparation, and optimize homology arm length

- Vector Self-Ligation: Implement robust counter-selection (e.g., lacZ blue/white screening) and consider additional purification steps after cleavage

- Heterologous Expression Failure: Optimize codon usage, promoter elements, and consider different chassis organisms for expression of captured BGCs

The vast majority of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) in microorganisms remain silent or "cryptic" under standard laboratory conditions, presenting a significant challenge and opportunity for natural product discovery [30] [31]. Activating these cryptic pathways is essential for accessing novel chemical compounds with potential pharmaceutical applications. This application note details a case study utilizing the CAT-FISHING (CRISPR/Cas12a-mediated fast direct biosynthetic gene cluster cloning) method to directly clone and heterologously express a cryptic gene cluster, leading to the discovery of marinolactam A, a novel macrolactam with promising anticancer activity [32]. The methodology and principles described herein are framed within the broader context of direct cloning strategies for large genomic fragments, a field rapidly advancing through innovations in molecular biology [28].

Key Principles of Direct Cloning for Cryptic Gene Clusters

Direct cloning strategies bypass the need for traditional library construction and screening, enabling targeted capture and heterologous expression of large BGCs. These methods generally address three critical steps: (1) preparation of high-quality genomic DNA, (2) precise release of the target BGC from the genome, and (3) efficient assembly of the fragment into a suitable capture vector [3].

The transition from analyzing life to rewriting it necessitates technologies capable of manipulating large DNA segments. While restriction enzymes were foundational, the programmability of CRISPR/Cas systems has driven their extensive adoption for fragment release due to their flexibility and precision [28]. For capturing the released fragments, techniques such as Homologous Recombination (HR), single-strand annealing (SSA), and site-specific recombination (SSR) have been optimized to meet diverse cloning needs [28].

The CAT-FISHING Methodology

The CAT-FISHING platform combines the programmability of the CRISPR/Cas12a system with refined aspects of bacterial artificial chromosome (BAC) library construction, creating an efficient in vitro platform for capturing large BGCs [32].

Experimental Workflow and Protocol

The following diagram illustrates the key stages of the CAT-FISHING protocol for direct cloning and activation of a cryptic biosynthetic gene cluster.

Step 1: Target Identification and gDNA Preparation

- Bioinformatic Analysis: Identify the cryptic BGC of interest (e.g., a polyketide-derived macrolactam cluster) using tools like antiSMASH [33] [34].

- gDNA Isolation: Extract high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from the source actinomycete, Micromonospora sp. 181, using a standard phenol-chloroform protocol. Assess DNA integrity and purity via agarose gel electrophoresis and spectrophotometry.

Step 2: Cas12a-Mediated Fragment Release

- crRNA Design: Design and synthesize two crRNAs targeting sequences immediately upstream and downstream of the ~110 kb target BGC.

- In Vitro Digestion: Set up a 50 µL reaction containing:

- 1-5 µg of genomic DNA

- 200 nM of each crRNA

- 50 nM Lachnospiraceae bacterium Cas12a (LbCas12a) enzyme

- 1X Cas12a reaction buffer

- Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours. Heat-inactivate the enzyme at 65°C for 20 minutes.

Step 3: Vector Preparation and Capture

- Linearize the Capture Vector (e.g., a BAC vector) using restriction enzymes or PCR.

- Generate Homology Arms: Amplify by PCR two ~800 bp homology arms that correspond to the ends of the target BGC. Clone these into the linearized vector.

- Assemble the Construct: Use an in vitro recombination system (e.g., Gibson Assembly) to combine the Cas12a-released genomic fragment with the prepared capture vector.

- Transform the assembled product into competent E. coli cells and select on appropriate antibiotic plates.

Step 4: Heterologous Expression

- Isolate the Plasmid containing the captured BGC from E. coli.

- Transform the plasmid into a suitable Streptomyces expression chassis (e.g., S. coelicolor or S. lividans) via protoplast transformation or conjugation.

- Culture the recombinant strain in appropriate liquid media for 5-7 days to allow for compound production.

Step 5: Compound Isolation and Characterization

- Extract metabolites from the culture broth using organic solvents (e.g., ethyl acetate).

- Purify the compound of interest using chromatographic methods (HPLC, silica gel).

- Characterize the structure using spectroscopic techniques (LC-MS, NMR).

Performance Metrics of CAT-FISHING

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the CAT-FISHING Method in the Marinolactam A Study

| Parameter | Performance | Experimental Details |

|---|---|---|

| Maximum BGC Size Captured | 145 kb | Successfully cloned from actinomycetal genomic DNA [32]. |

| GC Content Tolerance | Up to 75% | Demonstrated with high-GC content BGCs [32]. |

| Target BGC Size | 110 kb | The specific marinolactam A cluster from Micromonospora sp. 181 [32]. |

| Key Outcome | Discovery of Marinolactam A | A novel macrolactam with promising anticancer activity [32]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Solutions for CAT-FISHING

| Reagent/Solution | Function | Specific Example/Note |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas12a System | Programmable enzymatic release of the target BGC from gDNA. | Lachnospiraceae bacterium Cas12a (LbCas12a) was used for its precision and efficiency [32]. |

| Homology Arms | Facilitate precise recombination between the vector and target DNA ends. | ~800 bp arms designed based on BGC flanking sequences; critical for capture success [32]. |

| BAC (Bacterial Artificial Chromosome) Vector | Stable maintenance and propagation of large DNA inserts in E. coli. | Essential for cloning fragments >100 kb without instability [35]. |

| Heterologous Chassis | Provides a tractable background for expressing silent BGCs. | A Streptomyces species (e.g., S. coelicolor) is often optimal for actinomycete BGCs [32] [31]. |

| In Vitro Recombination Kit | Seamlessly assembles the released fragment and linearized vector. | Gibson Assembly is a common choice, though other methods exist [36] [31]. |

Discussion and Comparative Analysis

The success of CAT-FISHING in discovering marinolactam A underscores the power of direct cloning approaches in functional genomics and natural product discovery. This method effectively addresses several challenges: it is independent of the host's genetic tractability, avoids the time-consuming process of library screening, and minimizes the introduction of mutations that can occur during PCR-based assembly [32] [36].

CAT-FISHING is one of several advanced direct cloning methods. Other notable techniques include CAPTURE, which uses Cas12a and in vivo Cre-lox recombination and has demonstrated success in cloning 47 BGCs with nearly 100% efficiency, leading to the discovery of 15 novel natural products [37]. Similarly, RecET-mediated linear-plus-linear homologous recombination (LLHR) has been used to clone gene clusters up to 52 kb from Photorhabdus luminescens [36] [35].

A primary advantage of CRISPR-based methods like CAT-FISHING is their programmability, which allows for precise targeting without reliance on rare restriction enzyme sites [28] [3]. Furthermore, direct cloning preserves the native genetic context of the BGC, which can be crucial for successful expression, though it does not guarantee it. The heterologous host may still lack necessary activators or contain incompatible regulatory elements [36].

The CAT-FISHING method represents a significant asset in the growing toolkit for direct cloning of large genomic fragments. By enabling the efficient capture and heterologous expression of a 110 kb cryptic gene cluster, it facilitated the discovery of marinolactam A, demonstrating a clear path from genomic sequence to novel bioactive compound. As direct cloning technologies continue to evolve, they will undoubtedly accelerate the systematic mining of microbial genomes, fueling the discovery of new drugs and biomaterials from nature's vast, untapped genetic reservoir.

The rapidly expanding repository of microbial genomic data has revealed a vast, untapped reservoir of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) that encode for potentially novel bioactive natural products [38]. This discovery is particularly significant for drug development, as natural products and their derivatives constitute a substantial proportion of clinical drugs, including 61% of anticancer drugs and 49% of anti-infection medicines [39]. However, a significant challenge persists: the majority of these BGCs are "silent" or "cryptic," meaning they are poorly expressed or not expressed at all under standard laboratory conditions [38] [3]. This limitation impedes the discovery and characterization of novel compounds, necessitating robust strategies to access this chemical diversity.