From Concept to Cure: The Evolution of Molecular Engineering in Modern Drug Discovery

This article traces the transformative journey of molecular engineering from its foundational principles to its current status as a cornerstone of modern therapeutics.

From Concept to Cure: The Evolution of Molecular Engineering in Modern Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article traces the transformative journey of molecular engineering from its foundational principles to its current status as a cornerstone of modern therapeutics. Designed for researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals, it explores the methodological shifts from traditional design to AI-driven generation, delves into optimization strategies for complex challenges like molecular validity and specificity, and validates progress through comparative analysis of 3D generative models and real-world case studies. By synthesizing key technological breakthroughs and their applications in areas such as targeted protein degradation, radiopharmaceuticals, and cell therapy, this review provides a comprehensive resource for understanding how molecular engineering is reshaping the landscape of biomedical research and clinical development.

The Roots of Control: Tracing the Foundational Shifts in Molecular Design

Molecular engineering represents a fundamental paradigm shift in the scientific approach to technology development. Moving beyond the traditional observational and correlative methods of classical science, this discipline employs a rational, "bottom-up" methodology to design and assemble materials, devices, and systems with specific functions directly from their molecular components [1] [2]. This whitepaper examines the historical evolution of molecular engineering, delineates its core principles against those of conventional science, and provides a detailed examination of its methodologies and applications, with particular emphasis on advancements in drug development and biomedical technologies.

Historical Foundation and Paradigm Shift

The conceptual foundation of molecular engineering was first articulated in 1956 by Arthur R. von Hippel, who defined it as "… a new mode of thinking about engineering problems. Instead of taking prefabricated materials and trying to devise engineering applications consistent with their macroscopic properties, one builds materials from their atoms and molecules for the purpose at hand" [2]. This emerging perspective stood in stark contrast to the established traditions of molecular biology and biochemistry, which were primarily observational sciences focused on unraveling functional relationships and understanding existing biological systems [3] [4].

The field gained further momentum with the rise of molecular biology in the 1960s and 1970s, which introduced powerful new tools for understanding life at the molecular level [3]. However, a significant epistemological divide emerged during what has been termed the "molecular wars," where traditional evolutionary biologists championed the distinction between functional biology (addressing "how" questions) and evolutionary biology (addressing "why" questions), while molecular biologists began asserting the significance of "informational macromolecules" for all biological processes [3]. Molecular engineering transcends this dichotomy by introducing a third modality: "how can we build?" This represents a shift from descriptive science to prescriptive engineering, from analyzing what exists to creating what does not.

The table below contrasts the fundamental characteristics of the traditional observational science paradigm with the emerging molecular engineering paradigm:

Table 1: Paradigm Shift from Observational Science to Molecular Engineering

| Aspect | Observational Science Paradigm | Molecular Engineering Paradigm |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Goal | Understand and describe natural phenomena [3] | Design and construct functional systems from molecular components [2] |

| Approach | Analysis, hypothesis testing, correlation [4] | Rational design, synthesis, and assembly [2] |

| Mindset | "What is?" and "Why is it?" [3] | "How can we build?" and "What can we create?" [2] |

| Methodology | Often trial-and-error with prefabricated materials [2] | Bottom-up design from first principles [1] [2] |

| Outcome | Knowledge, theories, explanations | Functional materials, devices, and technologies [2] |

Core Principles of Molecular Engineering

The "Bottom-Up" Design Philosophy

At its core, molecular engineering operates on a "bottom-up" design philosophy where observable properties of a macroscopic system are influenced by the direct alteration of molecular structure [2]. This approach involves selecting molecules with the precise chemical, physical, and structural properties required for a specific function, then organizing them into nanoscale architectures to achieve a desired product or process [1]. This stands in direct opposition to the traditional engineering approach of taking prefabricated materials and devising applications consistent with their existing macroscopic properties [2].

Rational Design vs. Trial-and-Error

A defining characteristic of molecular engineering is its commitment to a rational engineering methodology based on molecular principles, which contrasts sharply with the widespread trial-and-error approaches common throughout many engineering disciplines [2]. Rather than relying on well-described but poorly-understood empirical correlations between a system's makeup and its properties, molecular engineering seeks to manipulate system properties directly using an understanding of their chemical and physical origins [2]. This principles-based approach becomes increasingly crucial as technology advances and trial-and-error methods become prohibitively costly and difficult for complex systems where accounting for all variable dependencies is challenging [2].

Cross-Disciplinary Integration

Molecular engineering is inherently highly interdisciplinary, encompassing aspects of chemical engineering, materials science, bioengineering, electrical engineering, physics, mechanical engineering, and chemistry [2]. There is also considerable overlap with nanotechnology, as both are concerned with material behavior on the scale of nanometers or smaller [2]. This interdisciplinary nature requires engineers who are conversant across multiple disciplines to address the field's complex target problems [2].

Key Technological Applications

The molecular engineering paradigm has enabled breakthroughs across numerous industries. The following table summarizes transformative applications in key sectors, particularly highlighting advances relevant to drug development professionals.

Table 2: Key Applications of Molecular Engineering Across Industries

| Field | Application | Molecular Engineering Approach | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Immunotherapy | Peptide-based vaccines [2] | Amphiphilic peptide macromolecular assemblies designed to induce robust immune response | Enhanced vaccine efficacy and targeted immune activation |

| Biopharmaceuticals | Drug delivery systems [2] | Design of nanoparticles, liposomes, and polyelectrolyte micelles as delivery vehicles | Improved drug bioavailability and targeted delivery |

| Gene Therapy | CRISPR and gene delivery [2] | Designing molecules to deliver modified genes into cells to cure genetic disorders | Precision medicine and treatment of genetic diseases |

| Medical Devices | Antibiotic surfaces [2] | Incorporation of silver nanoparticles or antibacterial peptides into coatings | Prevention of microbial infection on implants and devices |

| Energy Storage | Flow batteries [2] | Synthesizing molecules for high-energy density electrolytes and selective membranes | Grid-scale energy storage with improved efficiency |

| Environmental Engineering | Water desalination [2] | Designing new membranes for highly-efficient low-cost ion removal | Sustainable water purification solutions |

Experimental Methodologies and Protocols

Essential Research Reagents and Solutions

Molecular engineering research requires specialized reagents and materials to enable precise manipulation at the molecular scale. The following table catalogues critical resources for experimental work in this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Engineering

| Reagent/Material | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|

| Functionalized Monomers | Building blocks for synthetic polymers | Creating tailored biomaterials, drug delivery vehicles [2] |

| Amphiphilic Peptides | Self-assembling structural elements | Vaccine development, nanostructure fabrication [2] |

| Silver Nanoparticles | Antimicrobial agents | Antibiotic surface coatings for medical devices [2] |

| DNA-conjugated Nanoparticles | Programmable assembly units | 3D nanostructure lattices, functional materials [2] |

| Organic Semiconductor Molecules | Electronic materials | Organic light-emitting diodes (OLEDs), flexible electronics [2] |

| Liposome Formulations | Drug encapsulation and delivery | Targeted therapeutic delivery, membrane studies [5] |

Detailed Protocol: Molecular Engineering of Cell Membranes

Chemical engineering of cell membranes represents a powerful methodology for manipulating surface composition and controlling cellular interactions with the environment [5]. The protocol below outlines a covalent ligation strategy for cell surface modification.

Objective: To covalently attach functional molecules to cell surface proteins or lipids via bioorthogonal chemistry.

Materials and Reagents:

- Target cells in appropriate growth medium

- N-hydroxysuccinimide (NHS) ester of desired functional molecule (e.g., fluorescent dye, biotin, peptide)

- Phosphate-buffered saline (PBS), pH 7.4

- Quenching solution (e.g., Tris buffer or glycine)

- Flow cytometry analysis reagents (if using fluorescent labels)

Procedure:

- Cell Preparation: Harvest and wash cells three times with PBS to remove serum proteins that might react with the NHS ester.

- Reaction Preparation: Dissolve NHS-ester functional molecule in anhydrous DMSO immediately before use to prevent hydrolysis.

- Labeling Reaction: Resuspend cells in PBS at a concentration of 1-5 × 10^6 cells/mL. Add NHS-ester solution to achieve final concentration of 10-100 µM. Incubate with gentle mixing for 15-30 minutes at 4°C to minimize internalization.

- Reaction Quenching: Add excess quenching solution (100 mM Tris or glycine) and incubate for 5 minutes to neutralize unreacted NHS esters.

- Washing and Analysis: Wash cells three times with PBS containing 1% FBS to remove unbound molecules. Analyze modification efficiency via flow cytometry (for fluorescent labels) or functional assays.

Critical Considerations:

- Maintain cell viability throughout by working quickly at 4°C and using proper sterile technique.

- Optimize reagent concentration and reaction time for each cell type to balance labeling efficiency with viability.

- Include appropriate controls (untreated cells, DMSO-only treated) to account for non-specific effects.

- For therapeutic applications, thoroughly assess functional consequences of modification on cell behavior [5].

Computational and Analytical Techniques

Molecular engineering employs sophisticated computational and analytical tools for design and validation:

Computational Approaches:

- Molecular dynamics simulations for predicting molecular behavior

- Quantum mechanics calculations for electronic properties

- Finite element analysis for system performance modeling [2]

Characterization Methods:

- Atomic force microscopy (AFM) for surface topography

- X-ray diffraction (XRD) for structural analysis

- Spectroscopy techniques (NMR, MS, FTIR) for molecular characterization [2] [5]

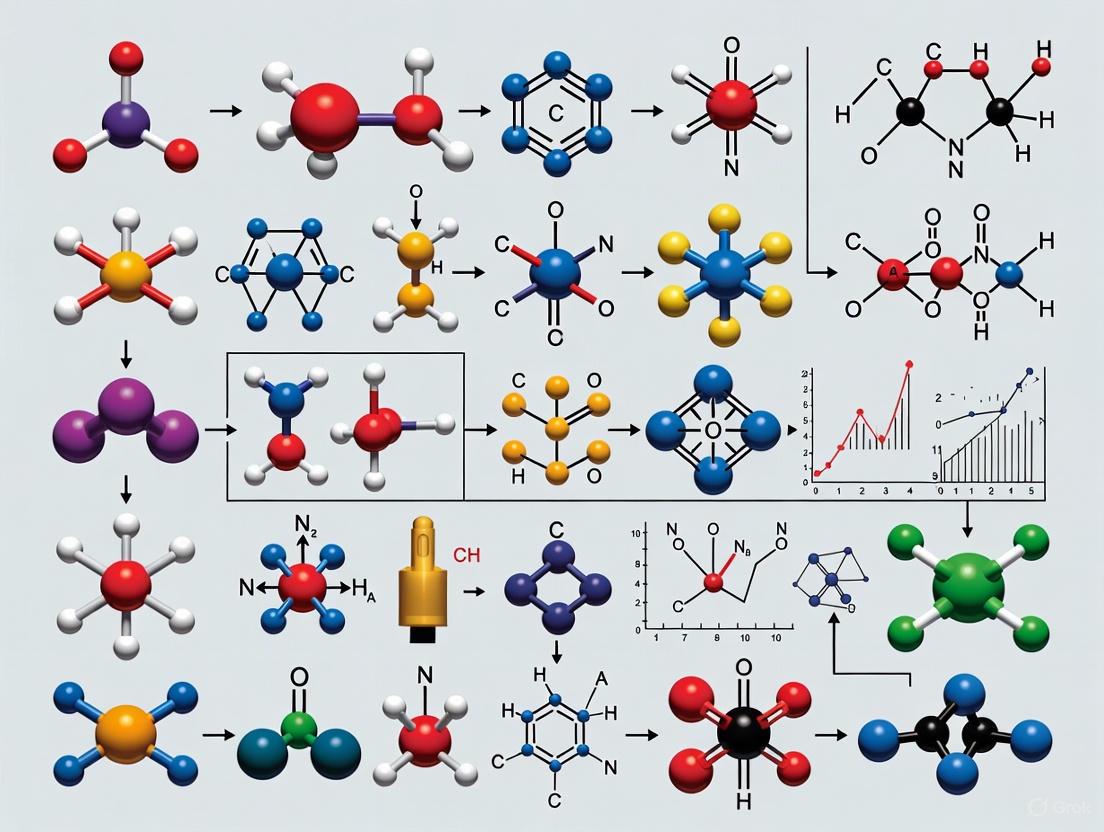

The following diagram illustrates a generalized workflow for rational molecular design, integrating computational and experimental approaches:

Current Research Frontiers and Future Directions

Quantitative Biology and Systems Integration

The last decade has witnessed a profound transformation in molecular biology research, fueled by revolutionary technologies that enable systematic and quantitative measurement of molecules and cells [6]. This technological leap presents an opportunity to describe biological systems quantitatively to formulate mechanistic models and confront the grand challenge of engineering new cellular behaviors [6]. The integration of genomics, proteomics, and quantitative imaging generates vast amounts of high-resolution data characterizing biological systems across multiple scales, creating a foundation for more predictive molecular engineering [6].

Molecular Visualization and Communication

Effective molecular visualization plays a crucial role in the molecular engineering paradigm, serving as a bridge between computational design and physical implementation [7]. Current research focuses on developing best practices for color palettes in molecular visualization to enhance interpretability and effectiveness without compromising aesthetics [7]. Semantic color use in molecular storytelling—such as identifying key molecules in signaling pathways or establishing visual hierarchies—improves communication of complex molecular mechanisms to diverse audiences, from research scientists to clinical practitioners [7].

Educational Framework Development

The formalization of molecular engineering as a distinct discipline is reflected in the establishment of dedicated academic programs at leading institutions such as the University of Chicago's Pritzker School of Molecular Engineering [8]. These programs develop cutting-edge engineering curricula built on strong foundations in mathematics, physics, chemistry, and biology, with specialized tracks in bioengineering, chemical engineering, and quantum engineering [8]. This educational evolution signals the maturation of molecular engineering from a conceptual framework to an established engineering discipline with standardized methodologies.

Molecular engineering represents a fundamental shift from observational science to direct engineering at the molecular scale. By combining rational design principles with advanced computational and experimental techniques, this paradigm enables the creation of functional systems with precision that was previously unattainable. For drug development professionals, molecular engineering offers powerful new approaches to therapeutic design, from targeted drug delivery systems to engineered cellular therapies. As the field continues to evolve through advances in quantitative biology, improved visualization techniques, and formalized educational frameworks, its impact on medicine and technology is poised to grow exponentially, ultimately enabling more precise, effective, and personalized healthcare solutions.

The evolution of molecular engineering is a history of tool creation. The ability to precisely manipulate matter at the molecular level has fundamentally transformed biological research and drug development, enabling advances from recombinant protein therapeutics to gene editing. This progression from macroscopic observation to atomic-level control represents a paradigm shift in scientific capability, driven by the continuous refinement of techniques for observing, measuring, and altering molecular structures. This technical guide traces the key instrumental and methodological milestones that have enabled this precision manipulation, providing researchers with a comprehensive overview of the tools that underpin modern molecular engineering.

The Foundational Era: Establishing Molecular Understanding

The initial phase of molecular manipulation was characterized by the development of tools to decipher the basic structures and codes of biological systems, moving from cellular observation to genetic understanding.

Key Historical Developments (1857-1970)

Table 1: Foundational Discoveries in Molecular Biology

| Year | Development | Key Researchers/Proponents | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1857 | Role of microbes in fermentation | Louis Pasteur [9] | Established biological catalysis |

| 1865 | Laws of Inheritance | Gregor Mendel [10] [11] [9] | Defined genetic inheritance patterns |

| 1953 | Double-helical DNA structure | James Watson, Francis Crick [10] [11] [12] | Revealed molecular basis of genetics |

| 1966 | Genetic code established | Nirenberg, Khorana, others [10] [11] | Deciphered DNA-to-protein translation |

| 1970 | Restriction enzymes discovered | Hamilton Smith [12] | Provided "molecular scissors" for DNA cutting |

Experimental Analysis: Griffith's Transforming Principle (1928)

Objective: To determine the mechanism of bacterial virulence transformation.

Methodology:

- Heat-killed virulent strain preparation: Smooth (S) strain Streptococcus pneumoniae was heat-killed.

- Live non-virulent strain preparation: Rough (R) strain, avirulent, was cultured.

- Co-injection: Mixtures of heat-killed S strain and live R strain were injected into mice.

- Control groups: Mice injected with either strain alone (heat-killed S or live R).

- Outcome measurement: Survival and bacterial isolation from deceased mice.

Results: Mice injected with the mixture died. Live S strain bacteria were recovered, indicating a "transforming principle" from the dead S strain converted the live R strain to virulence [12].

Significance: This experiment indirectly demonstrated that genetic material could be transferred between cells, paving the way for the identification of DNA as the molecule of inheritance [12].

The Recombinant DNA Revolution: Cutting and Pasting Genes

The 1970s marked a turning point with the development of technologies to isolate, recombine, and replicate DNA sequences from different sources, establishing the core toolkit for genetic engineering.

Enabling Technologies and Milestones

Table 2: Key Tools for Recombinant DNA Technology

| Tool/Technique | Year | Function | Role in Genetic Engineering |

|---|---|---|---|

| DNA Ligase | 1967 [12] | Joins DNA strands [10] [12] | "Molecular glue" for assembling DNA fragments |

| Restriction Enzymes | 1970 [10] | Cuts DNA at specific sequences [10] [12] | "Molecular scissors" for precise DNA fragmentation |

| Plasmids | (Discovered 1952) [12] | Extrachromosomal circular DNA [12] | Vectors for DNA cloning and transfer |

| Chemical Transformation (CaCl₂) | 1970 [12] | Induces DNA uptake in E. coli [12] | Enabled introduction of recombinant DNA into host cells |

Experimental Protocol: Cohen-Boyer Recombinant DNA Cloning (1973)

Objective: To clone a functional gene from one organism into a bacterium.

Materials (Research Reagent Solutions):

- pSC101 plasmid: Contains tetracycline resistance gene; serves as cloning vector [12].

- Kanamycin resistance gene: Target DNA fragment to be cloned [12].

- Restriction enzyme (EcoRI): Cuts plasmid and foreign DNA at specific sites [12].

- DNA ligase: Joins compatible DNA ends [12].

- Calcium chloride-treated E. coli: Chemically competent cells for DNA uptake [12].

- Agar plates with antibiotics (tetracycline, kanamycin): For selection of transformed bacteria [12].

Procedure:

- Digestion: The pSC101 plasmid and the DNA containing the kanamycin resistance gene were digested with the restriction enzyme EcoRI [12].

- Ligation: The digested plasmid and foreign DNA fragments were mixed with DNA ligase to create recombinant molecules [12].

- Transformation: The ligation mixture was introduced into calcium chloride-treated E. coli cells [12].

- Selection: Transformed bacteria were selected by growth on agar plates containing both tetracycline and kanamycin [12].

- Verification: Bacterial colonies growing on both antibiotics were analyzed to confirm the presence of the recombinant plasmid [12].

Outcome: Creation of the first genetically modified organism—a bacterium expressing a cloned kanamycin resistance gene—demonstrating that genes could be transferred between species and remain functional [12].

Diagram 1: Recombinant DNA Cloning Workflow.

The Amplification and Sequencing Era: Reading and Copying DNA

The ability to rapidly amplify and sequence DNA provided the throughput necessary for systematic genetic analysis, culminating in the landmark Human Genome Project.

Key Technological Advances

Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) (1985): Developed by Kary Mullis, this technique uses thermal cycling and a heat-stable DNA polymerase to exponentially amplify specific DNA sequences, revolutionizing genetic analysis by generating millions of copies from a single template [12] [9].

DNA Sequencing Methods (1977): The development of chain-termination method (Sanger sequencing) and chemical cleavage method (Maxam-Gilbert sequencing) enabled the determination of nucleotide sequences, providing the fundamental tool for reading genetic information [10] [12].

The Human Genome Project (1990-2003)

This international effort to sequence the entire human genome drove and was enabled by dramatic improvements in sequencing technologies, moving from laborious manual methods to automated, high-throughput capillary systems [10] [11]. It established the reference human genome sequence, catalysing the development of bioinformatics and genomics-driven drug discovery [10].

Directed Evolution: Engineering Biomolecules through Artificial Selection

Directed evolution mimics natural selection in the laboratory to engineer proteins, pathways, or entire organisms with improved or novel functions.

Core Methodological Framework

The process is an iterative two-step cycle [13]:

- Library Creation: Generating genetic diversity in the target (e.g., a protein-encoding gene).

- Screening/Selection: Identifying variants with desired properties from the library.

The best performers become the templates for the next cycle.

Experimental Protocol: Directed Evolution of Subtilisin E for Organic Solvent Stability (1994)

Objective: Enhance the activity of subtilisin E protease in dimethylformamide (DMF) [13].

Materials:

- Subtilisin E gene: Template for diversification.

- Error-prone PCR reagents: Includes Taq polymerase (low fidelity), unbalanced dNTPs, Mn²⁺ to introduce random mutations [13].

- Expression vector and host: For protein production.

- Screening assay: Colorimetric or fluorogenic substrate to measure protease activity in DMF [13].

Procedure:

- Diversification: The subtilisin E gene was amplified using error-prone PCR conditions to introduce random point mutations [13].

- Library Construction: The mutated gene pool was cloned into an expression vector and transformed into a bacterial host [13].

- Screening: Individual colonies were expressed, and the corresponding enzyme extracts were assayed for protease activity in the presence of high concentrations of DMF [13].

- Selection: The variant showing the highest activity in DMF was selected [13].

- Iteration: Steps 1-4 were repeated for multiple rounds, using the best mutant from the previous round as the new template [13].

Outcome: After three rounds, a mutant with 6 amino acid substitutions was identified, exhibiting a 256-fold higher activity in 60% DMF compared to the wild-type enzyme [13].

Diagram 2: Directed Evolution Iterative Cycle.

The Modern Toolkit: CRISPR and Precision Genome Editing

The most recent transformative milestone is the development of CRISPR-Cas9 technology, which provides unprecedented precision for editing genomes.

The CRISPR-Cas9 System Components

Table 3: Key Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 Genome Editing

| Component | Type | Function |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Protein or gene encoding it | "Molecular scalpel" that cuts double-stranded DNA |

| sgRNA (Single-Guide RNA) | Synthesized RNA molecule | Combines targeting (crRNA) and scaffolding (tracrRNA) functions; guides Cas9 to specific genomic locus |

| Repair Template | Single-stranded oligo or double-stranded DNA vector | Optional; provides template for precise edits via HDR (Homology Directed Repair) |

| Delivery Vehicle | (e.g., Lipofectamine, viral vector) | Transports CRISPR components into the target cell |

Experimental Workflow: CRISPR-Cas9 Mediated Gene Knock-In

Objective: Insert a new DNA sequence (e.g., a reporter gene) into a specific genomic locus in mammalian cells.

Procedure:

- Target Selection & gRNA Design: A 20-nucleotide sequence adjacent to a PAM (Protospacer Adjacent Motif) site in the target gene is selected. The corresponding sgRNA is designed and synthesized [10].

- Component Preparation: A plasmid encoding the Cas9 nuclease and a second plasmid encoding the sgRNA and the reporter gene (repair template) are constructed [10].

- Delivery: Plasmids are co-transfected into the target cells using a method appropriate for the cell type (e.g., lipofection, electroporation) [10].

- DNA Cleavage & Repair: The Cas9/sgRNA complex binds the target locus and induces a double-strand break. The cell's HDR repair machinery uses the supplied repair template to integrate the reporter gene into the genome [10].

- Validation: Edited cells are screened via antibiotic selection and PCR/sequencing to confirm precise insertion [10].

Significance: CRISPR technology allows for precise, targeted modifications—corrections, insertions, deletions—in the genomes of live organisms, with profound implications for functional genomics, disease modeling, and gene therapy [10].

The history of precision manipulation in molecular engineering reveals a clear trajectory: from observing biological structures to directly rewriting them. Each major milestone—recombinant DNA, PCR, sequencing, directed evolution, and CRISPR—has provided a new class of tools that expanded the possible. These tools have converged to create a modern engineering discipline where biological systems can be designed and constructed with predictable outcomes. For drug development professionals, this toolkit has enabled the creation of previously unimaginable therapies, from monoclonal antibodies to personalized cell therapies. The continued refinement of these tools, particularly in the realms of gene editing and synthetic biology, promises to further accelerate the pace of therapeutic innovation.

The field of molecular engineering has witnessed numerous transformative breakthroughs, but few have redrawn the therapeutic landscape as profoundly as the development of Targeted Protein Degradation (TPD). For decades, drug discovery operated on the principle of occupancy-driven inhibition, where small molecules required continuous binding to active sites to block protein function [14]. This approach, while successful for many targets, left approximately 80-85% of the human proteome—particularly proteins lacking well-defined binding pockets such as transcription factors, scaffolding proteins, and regulatory subunits—largely inaccessible to therapeutic intervention [14] [15].

The conceptual foundation for proteolysis-targeting chimeras (PROTACs) was established in 2001 by the pioneering work of Crews and Deshaies, who introduced the first peptide-based PROTAC molecule [16] [17]. This initial construct demonstrated that heterobifunctional molecules could hijack cellular quality control machinery to eliminate specific proteins. The technology transitioned from concept to therapeutic reality in 2008 with the development of the first small-molecule PROTACs, which offered improved cellular permeability and pharmacokinetic properties over their peptide-based predecessors [18] [17]. The field has since accelerated dramatically, with the first PROTAC entering clinical trials in 2019 and, remarkably, achieving Phase III completion by 2024 [14].

This technical guide examines the rise of PROTAC technology within the broader context of molecular engineering, detailing its mechanistic foundations, design principles, experimental characterization, and clinical translation. As we explore this rapidly evolving landscape, we will highlight how PROTACs have not only expanded the druggable proteome but have fundamentally redefined what constitutes a tractable therapeutic target.

Mechanistic Foundations of PROTACs

Core Architecture and Mechanism

PROTACs are heterobifunctional small molecules comprising three fundamental components: (1) a ligand that binds to the protein of interest (POI), (2) a ligand that recruits an E3 ubiquitin ligase, and (3) a chemical linker that covalently connects these two moieties [19] [16] [14]. This tripartite structure enables PROTACs to orchestrate a unique biological process: instead of merely inhibiting their targets, they facilitate the complete elimination of pathogenic proteins from cells.

The molecular mechanism of PROTAC action exploits the ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS), the primary pathway for controlled intracellular protein degradation in eukaryotic cells [20] [17]. The process occurs through a carefully coordinated sequence:

- Target Binding: The PROTAC molecule enters the cell and binds to the target protein through its POI-binding ligand [19].

- E3 Ligase Recruitment: Simultaneously, the PROTAC's E3 ligase ligand engages a specific E3 ubiquitin ligase [19].

- Ternary Complex Formation: The PROTAC induces a transient complex between the target protein and the E3 ubiquitin ligase [19] [14].

- Ubiquitination: The E3 ligase transfers polyubiquitin chains to lysine residues on the surface of the target protein [19] [17].

- Degradation: The ubiquitin-tagged protein is recognized and degraded by the 26S proteasome, while the PROTAC molecule is recycled to initiate additional degradation cycles [19].

This mechanism represents a shift from traditional occupancy-driven pharmacology to event-driven pharmacology, where the therapeutic effect stems from a catalytic process rather than continuous target occupancy [14]. This fundamental distinction underpins many of the unique advantages of PROTAC technology.

Diagram 1: The PROTAC Mechanism of Action. A PROTAC molecule acts as a molecular bridge to bring an E3 ubiquitin ligase to the target protein, facilitating its ubiquitination and subsequent degradation by the proteasome. The PROTAC is then recycled for further catalytic activity.

Key Advantages Over Traditional Therapeutics

PROTAC technology offers several distinct pharmacological advantages that differentiate it from conventional small molecule inhibitors:

Expansion of the Druggable Proteome: By relying on binding-induced proximity rather than active-site inhibition, PROTACs can target proteins previously considered "undruggable," including transcription factors, scaffolding proteins, and non-enzymatic regulatory elements [20] [19] [14]. This potentially unlocks therapeutic access to a significant portion of the proteome that was previously inaccessible to conventional small molecules [15].

Catalytic Efficiency and Sub-stoichiometric Activity: PROTACs operate catalytically; a single molecule can facilitate the degradation of multiple target protein molecules through successive cycles of binding, ubiquitination, and release [19] [14] [15]. This sub-stoichiometric mechanism can produce potent effects at lower concentrations than required for traditional inhibitors [19].

Overcoming Drug Resistance: Conventional inhibitors often face resistance through target overexpression or mutations that reduce drug binding. By degrading the target protein completely, PROTACs can circumvent both mechanisms [20] [19] [17]. For example, BTK degraders have shown clinical activity against both wild-type and C481-mutant BTK in B-cell malignancies [19].

Sustained Pharmacological Effects: Since degradation eliminates the target protein entirely, pharmacological effects persist until the protein is resynthesized through natural cellular processes. This provides prolonged target suppression even after the PROTAC has been cleared from the system [19].

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of PROTACs Versus Traditional Small Molecule Inhibitors

| Characteristic | Traditional Small Molecule Inhibitors | PROTAC Degraders |

|---|---|---|

| Mechanism of Action | Occupancy-driven inhibition [14] | Event-driven degradation [14] |

| Target Scope | ~15% of proteome (proteins with defined binding pockets) [14] | Potentially much larger (includes "undruggable" proteins) [14] [15] |

| Dosing Requirement | Sustained high concentration for continuous inhibition [21] | Lower, pulsed dosing due to catalytic mechanism [19] [15] |

| Effect on Protein | Inhibits function | Eliminates protein entirely |

| Duration of Effect | Short (requires continuous presence) [21] | Long-lasting (until protein resynthesis) [19] |

| Resistance Mechanisms | Target mutation/overexpression [18] | May overcome many resistance mechanisms [20] [19] |

The PROTAC Development Toolkit

Key Research Reagents and Materials

The design and validation of PROTAC molecules require specialized reagents and methodologies. The table below outlines essential components of the PROTAC research toolkit.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for PROTAC Development

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function in PROTAC Development |

|---|---|---|

| E3 Ligase Ligands | VHL ligands (e.g., VH032), CRBN ligands (e.g., Pomalidomide), MDM2 ligands (e.g., Nutlin-3) [18] | Recruit specific E3 ubiquitin ligase complexes to enable target ubiquitination [19] [18] |

| Target Protein Ligands | Kinase inhibitors, receptor antagonists, transcription factor binders [21] | Bind specifically to the protein targeted for degradation [19] |

| Linker Libraries | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains, alkyl chains, piperazine-based linkers [16] | Connect E3 and POI ligands; optimize spatial orientation for ternary complex formation [16] [14] |

| Cell Lines with Endogenous Targets | Cancer cell lines expressing target proteins (e.g., BTK in Ramos cells, ER in breast cancer models) [16] | Evaluate PROTAC efficacy and selectivity in physiologically relevant systems [21] |

| Proteasome Inhibitors | MG-132, Bortezomib, Carfilzomib [17] | Confirm proteasome-dependent degradation mechanism [17] |

| Ubiquitination Assay Kits | ELISA-based ubiquitination assays, ubiquitin binding domains [17] | Detect and quantify target protein ubiquitination [17] |

| Ternary Complex Assays | Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR), Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC) [14] | Characterize formation and stability of POI-PROTAC-E3 complex [14] |

E3 Ligase Toolkit Expansion

While the human genome encodes approximately 600 E3 ubiquitin ligases, current PROTAC designs predominantly utilize only a handful, with cereblon (CRBN) and von Hippel-Lindau (VHL) accounting for the majority of reported compounds [18] [22]. This limited repertoire represents a significant constraint in the field. Emerging research focuses on expanding the E3 ligase toolbox to include other ligases such as MDM2, IAPs, DCAF family members, and RNF4 [18] [14] [22].

Diversifying the E3 ligase repertoire offers several strategic advantages:

- Tissue-Specific Targeting: Exploiting ligases with restricted expression patterns can enable tissue-selective degradation [19] [22].

- Overcoming Resistance: Cancer cells may downregulate specific E3 ligases as a resistance mechanism; alternative ligases can bypass this limitation [19] [22].

- Expanded Target Scope: Different E3 ligases may exhibit varying efficiencies toward specific target classes or subcellular localizations [22].

Recent estimates indicate that only about 13 of the 600 human E3 ligases have been utilized in PROTAC designs to date, leaving approximately 98% of this target class unexplored for TPD applications [22]. This represents a substantial opportunity for future innovation in the field.

Experimental Protocols and Characterization

PROTAC Design and Optimization Workflow

Developing effective PROTAC degraders requires an iterative optimization process that balances multiple structural and functional parameters:

Target Assessment: Evaluate the target protein for ligandability, disease association, and potential susceptibility to degradation-based targeting [14].

Ligand Selection: Identify suitable ligands for the target protein and selected E3 ligase. These may include known inhibitors, antagonists, or allosteric modulators with confirmed binding activity [21].

Linker Design and Synthesis: Systematically vary linker length, composition, and rigidity to optimize ternary complex formation. Common linker strategies include polyethylene glycol (PEG) chains, alkyl chains, and piperazine-based structures [16] [14].

In Vitro Screening: Assess degradation efficiency, potency (DC50), and maximum degradation (Dmax) in relevant cell lines using immunoblotting or other protein quantification methods [21].

Mechanistic Validation: Confirm UPS-dependent degradation using proteasome inhibitors (e.g., MG-132) and ubiquitination assays [17].

Selectivity Profiling: Evaluate off-target effects using proteomic approaches such as mass spectrometry-based proteomics to assess global protein abundance changes [22].

Functional Characterization: Determine phenotypic consequences of target degradation through cell proliferation assays, signaling pathway analysis, or other disease-relevant functional readouts [21].

Key Assays for PROTAC Characterization

Degradation Kinetics and Efficiency

PROTAC activity is typically quantified using two key parameters: DC50 (concentration achieving 50% degradation) and Dmax (maximum degradation achieved) [14]. These values are determined through dose-response experiments in which target protein levels are measured following PROTAC treatment, typically via immunoblotting or cellular thermal shift assays (CETSA) [14].

The hook effect represents a unique challenge in PROTAC optimization, where degradation efficiency decreases at high concentrations due to the formation of unproductive binary complexes (POI-PROTAC and E3-PROTAC) that compete with productive ternary complexes [18] [14] [15]. This phenomenon must be carefully characterized during dose-response studies.

Diagram 2: The Hook Effect in PROTAC Activity. At high concentrations, PROTAC molecules form unproductive binary complexes with either the target protein or E3 ligase alone, which compete with the formation of productive ternary complexes and reduce degradation efficiency.

Ternary Complex Analysis

The formation and stability of the POI-PROTAC-E3 ternary complex is a critical determinant of degradation efficiency [14]. Several biophysical techniques are employed to characterize this complex:

- Surface Plasmon Resonance (SPR): Measures binding kinetics and affinity in real-time [14].

- Analytical Ultracentrifugation (AUC): Assesses complex stoichiometry and hydrodynamic properties [14].

- Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM): Provides high-resolution structural information on complex formation [19].

- Cooperativity Assays: Quantify the enhanced binding affinity that occurs when both proteins simultaneously engage the PROTAC [14].

Selectivity and Off-Target Assessment

Comprehensive selectivity profiling is essential for PROTAC development. While the catalytic nature of PROTACs offers potential selectivity advantages, off-target degradation remains a concern [19] [22]. Advanced proteomic approaches enable system-wide monitoring of PROTAC effects:

- Global Proteomics: Mass spectrometry-based quantification of protein abundance changes across the proteome [22].

- Phosphoproteomics: Analysis of phosphorylation state changes to identify downstream signaling consequences [22].

- Interaction Proteomics: Mapping of changes in protein-protein interaction networks following target degradation [22].

Clinical Translation and Emerging Applications

Current Clinical Landscape

The PROTAC platform has rapidly advanced from preclinical validation to clinical evaluation. As of 2025, there are over 30 PROTAC candidates in various stages of clinical development, spanning Phase I to Phase III trials [16]. Notable examples include:

- Vepdegestrant (ARV-471): An oral estrogen receptor-targeting PROTAC that has advanced to Phase III trials (VERITAC-2) for ER+/HER2- breast cancer, with positive topline results reported in 2025 [19].

- Bavdegalutamide (ARV-110): An androgen receptor degrader evaluated in Phase I/II studies for metastatic castration-resistant prostate cancer [19] [16].

- NX-2127: A BTK degrader demonstrating clinical activity against both wild-type and C481-mutant BTK in B-cell malignancies [19].

These clinical candidates illustrate the potential of PROTAC technology to address significant challenges in oncology, particularly in overcoming resistance to conventional targeted therapies [20] [19].

Emerging Innovations and Future Directions

Conditional and Controlled Degradation

Next-generation PROTAC platforms are incorporating conditional activation mechanisms to enhance spatial and temporal precision:

- Photoactivatable PROTACs (opto-PROTACs): Utilize photolabile caging groups (e.g., DMNB, DEACM) on critical functional elements that can be removed with light exposure, enabling spatiotemporal control of degradation [16]. For example, Xue et al. developed BRD4-targeting photocaged degraders that achieved light-dependent BRD4 degradation in zebrafish embryo models [16].

- Pro-PROTACs (Latent PROTACs): Prodrug strategies where the active PROTAC is released under specific physiological conditions or through enzymatic activation, improving tissue specificity and pharmacokinetics [16].

Expanding Beyond Oncology

While cancer remains the most advanced application area, PROTAC technology is expanding into other therapeutic domains:

- Neurodegenerative Diseases: Targeting pathological proteins such as tau, α-synuclein, and TDP-43 in Alzheimer's, Parkinson's, and other neurodegenerative conditions [19] [23]. Blood-brain barrier penetration remains a significant challenge in this area [19] [23].

- Inflammatory and Immune Disorders: Developing degraders for transcription factors such as NF-κB and STAT proteins to modulate immune signaling [19].

- Metabolic Diseases: Exploring degradation-based approaches to targets involved in metabolic regulation [14].

Integration with Advanced Modalities

The future of PROTAC research involves integration with cutting-edge technologies:

- AI-Assisted Design: Platforms such as AIMLinker and DeepPROTAC use deep learning networks to generate novel linker moieties and predict ternary complex formation, accelerating rational PROTAC design [16].

- Multi-Omics Characterization: Integration of proteomics, phosphoproteomics, and metabolomics provides comprehensive insights into degrader mechanisms, selectivity, and efficacy [22].

- Advanced Delivery Systems: Development of nano-PROTACs, peptide-PROTACs, and biomacromolecule conjugates to overcome physicochemical limitations and improve tissue targeting [22].

PROTAC technology represents a fundamental paradigm shift in molecular engineering and therapeutic intervention. By transitioning from occupancy-driven inhibition to event-driven degradation, this approach has expanded the druggable proteome to include previously inaccessible targets, offering new hope for treating complex diseases. The rapid clinical advancement of PROTAC candidates demonstrates the translational potential of this platform, while ongoing innovations in E3 ligase recruitment, conditional degradation, and targeted delivery promise to further enhance the specificity and utility of this transformative technology.

As the field continues to evolve, the integration of structural biology, computational design, and multi-omics characterization will enable increasingly sophisticated degrader architectures. The expansion of PROTAC applications beyond oncology to neurodegenerative, inflammatory, and metabolic disorders underscores the platform's versatility and potential for broad therapeutic impact. Within the historical context of molecular engineering, PROTACs stand as a testament to the power of biomimetic design—harnessing natural cellular machinery to achieve therapeutic outcomes that were once considered impossible.

The field of molecular engineering has been fundamentally transformed by the harnessing of natural biological systems, with the CRISPR-Cas9 system representing one of the most significant advancements. This revolutionary technology originated from the study of a primitive bacterial immune system that protects prokaryotes from viral invaders [24]. In nature, CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) functions as an adaptive immune mechanism in bacteria, allowing them to recognize and destroy foreign genetic material from previous infections [25]. The historical evolution of this technology demonstrates how fundamental research into microbial defense mechanisms has unlocked unprecedented capabilities for precise genetic manipulation across diverse biological systems, from microorganisms to humans.

The transformation of CRISPR from a natural bacterial system to a programmable gene-editing tool began in earnest in 2012, when researchers Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier demonstrated that the natural system could be repurposed to edit any DNA sequence with precision [24]. Their work revealed that the CRISPR system could be reduced to two primary components: a Cas9 protein that acts as molecular scissors to cut DNA, and a guide RNA that directs Cas9 to specific genetic sequences [25]. This breakthrough created a programmable system that was faster, more precise, and significantly less expensive than previous gene-editing tools like zinc-finger nucleases and TALENs [24]. The subsequent rapid adoption and refinement of CRISPR technology exemplifies how understanding and engineering natural systems has accelerated the pace of biological research and therapeutic development.

Molecular Mechanisms: The Architecture of a Bacterial Defense System

The core components of the natural CRISPR-Cas system have been systematically engineered to create a versatile genetic editing platform. In its native context, the system consists of two RNAs (crRNA and tracrRNA) and the Cas9 protein [25]. For research and therapeutic applications, these elements have been streamlined into a two-component system:

- Guide RNA (gRNA): A chimeric single guide RNA that combines the functions of the natural crRNA and tracrRNA. The 5' end of the gRNA contains a ~20 nucleotide spacer sequence that is complementary to the target DNA site, providing the targeting specificity of the system [25].

- Cas9 Nuclease: An RNA-directed endonuclease that creates double-stranded breaks (DSBs) in target DNA. Cas9 requires both binding to the gRNA and recognition of a short Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence adjacent to the target site [25]. The canonical PAM sequence for Streptococcus pyogenes Cas9 is 5'-NGG-3' [25].

The editing process initiates when the gRNA directs Cas9 to a complementary DNA sequence adjacent to a PAM site. Upon binding, Cas9 undergoes a conformational change that activates its nuclease domains, creating a precise double-strand break in the target DNA [25]. The cellular repair machinery then addresses this break through one of two primary pathways:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair pathway that often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) at the cut site, potentially disrupting gene function and creating knockout alleles [25].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A more precise repair mechanism that uses a template DNA molecule to guide accurate repair, enabling specific genetic alterations or insertions when a repair template is provided [25].

Figure 1: Molecular mechanism of CRISPR-Cas9 system showing target recognition, DNA cleavage, and cellular repair pathways

Technical Evolution: Enhancing Precision and Expanding Capabilities

Since its initial development, the CRISPR toolkit has expanded dramatically beyond the standard CRISPR-Cas9 system, with numerous engineered variants that address limitations of the original platform and enable new functionalities.

Advanced Editing Systems

Base editing represents a significant advancement that addresses key limitations of traditional CRISPR systems. Rather than creating double-strand breaks, base editors directly convert one DNA base to another without cleaving the DNA backbone [24]. These systems fuse a catalytically impaired Cas protein (nCas9) to a deaminase enzyme, enabling direct chemical conversion of cytosine to thymine (C→T) or adenine to guanine (A→G) [26]. This approach reduces indel formation and improves editing efficiency for certain applications.

Prime editing further expands capabilities by enabling all 12 possible base-to-base conversions, as well as small insertions and deletions, without requiring double-strand breaks [27]. The system uses a prime editing guide RNA (pegRNA) that both specifies the target site and encodes the desired edit, along with a reverse transcriptase enzyme fused to Cas9 [27]. Prime editors offer greater precision and reduced off-target effects compared to traditional CRISPR systems.

The DNA Typewriter system represents a novel application that leverages prime editing for molecular recording [27]. This technology uses a tandem array of partial CRISPR target sites ("DNA Tape") where sequential pegRNA-mediated edits record the identity and order of biological events [27]. In proof-of-concept studies, DNA Typewriter demonstrated the ability to record thousands of symbols and complex event histories, enabling lineage tracing in mammalian cells across multiple generations [27].

Delivery Systems and Optimization

Effective delivery of CRISPR components remains a critical challenge for both research and therapeutic applications. The field has developed multiple delivery strategies, each with distinct advantages and limitations:

- Lipid Nanoparticles (LNPs): These synthetic particles efficiently encapsulate and deliver CRISPR ribonucleoproteins or mRNA, particularly to liver tissues [28]. A key advantage is the potential for redosing, as demonstrated in clinical trials where multiple LNP administrations were safely delivered to enhance editing efficiency [28].

- Viral Vectors: Adeno-associated viruses (AAVs) offer efficient delivery but face limitations regarding packaging capacity and potential immunogenicity [28].

- Engineered Virus-Like Particles (eVLPs): These hybrid systems combine advantages of viral and non-viral delivery, offering efficient editing with reduced toxicity concerns [26].

Recent clinical advances have demonstrated the potential for personalized CRISPR therapies developed rapidly for individual patients. In a landmark 2025 case, researchers created a bespoke therapy for an infant with a rare metabolic disorder in just six months, from design to administration [28]. The therapy utilized LNP delivery and demonstrated the feasibility of creating patient-specific treatments for rare genetic conditions [28].

Quantitative Analysis: Performance Metrics and Clinical Outcomes

The advancement of CRISPR technology is reflected in quantitative improvements across key performance metrics, including editing efficiency, specificity, and therapeutic outcomes.

Table 1: CRISPR System Performance Metrics Across Applications

| Editing System | Typical Efficiency Range | Key Applications | Notable Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 | 30-80% indel rates [25] | Gene knockout, large deletions | High efficiency, well-characterized |

| Base Editing | 20-50% conversion rates [26] | Point mutation correction | Reduced indel formation, no DSBs |

| Prime Editing | 10-50% depending on target [27] [26] | Precise base changes, small edits | Versatile editing types, high precision |

| ARCUS Nucleases | 60-90% in lymphocytes, 30-40% in hepatocytes [26] | Gene insertion, therapeutic editing | Single-component system, high efficiency |

Table 2: Selected Clinical Trial Outcomes (2024-2025)

| Condition | CRISPR Approach | Key Efficacy Metrics | Clinical Stage |

|---|---|---|---|

| hATTR Amyloidosis | LNP-delivered Cas9 targeting TTR [28] | ~90% reduction in TTR protein sustained over 2 years [28] | Phase III |

| Hereditary Angioedema | LNP-Cas9 targeting kallikrein [28] | 86% reduction in kallikrein, 73% attack-free at 16 weeks [28] | Phase I/II |

| Sickle Cell Disease | Ex vivo editing of hematopoietic stem cells [24] | Elimination of vaso-occlusive crises in majority of patients [24] | Approved (Casgevy) |

| CPS1 Deficiency | Personalized in vivo LNP therapy [28] | Symptom improvement, reduced medication dependence [28] | Individualized trial |

Experimental Framework: Methodologies for Genome Engineering

The implementation of CRISPR-based genome editing requires careful experimental design and optimization. Below are detailed protocols for key applications in mammalian systems.

Mouse Genome Editing via Embryo Microinjection

The generation of genetically engineered mouse models using CRISPR involves several critical steps [25]:

Target Design and Validation:

- Identify target sites with 20-nucleotide specificity followed by a 3' NGG PAM sequence

- Evaluate potential off-target sites using computational tools (e.g., crispr.mit.edu)

- Select guides with high on-target efficiency scores (>50%) and minimal off-target potential [25]

Component Preparation:

- sgRNA Synthesis: Clone target sequence into sgRNA expression vector, followed by in vitro transcription to produce functional sgRNA

- Cas9 mRNA Preparation: Generate capped, polyadenylated Cas9 mRNA through in vitro transcription for efficient translation in embryos

- Repair Template Design: For knock-in approaches, design single-stranded oligonucleotides or double-stranded DNA templates with homology arms flanking the desired modification [25]

Embryo Manipulation and Microinjection:

- Harvest one-cell stage mouse embryos from superovulated females

- Prepare injection mixture containing sgRNA (50 ng/μL), Cas9 mRNA (100 ng/μL), and optional repair template

- Perform microinjection into cytoplasm or pronucleus of embryos

- Transfer viable embryos to pseudopregnant recipient females [25]

Genotype Analysis:

- Screen offspring for desired mutations using PCR amplification and sequencing of target loci

- Analyze potential off-target effects at predicted sites

- Establish stable lines from founder animals [25]

Figure 2: Comprehensive workflow for generating genetically engineered mouse models using CRISPR-Cas9

DNA Typewriter Implementation for Lineage Tracing

The DNA Typewriter system enables sequential recording of molecular events through prime editing [27]:

DNA Tape Design:

- Construct tandem arrays of partial CRISPR target sites

- Include an initial active site with complete spacer and PAM

- Design subsequent sites with 5' truncations requiring editing for activation [27]

pegRNA Library Design:

- Create prime editing guide RNAs with unique insertion sequences (symbols)

- Ensure each insertion contains a constant 3' portion that activates the subsequent target site

- Include variable 5' regions that encode event identity [27]

Cell Engineering and Recording:

- Stably integrate DNA Tape arrays into target cells using piggyBac transposition or similar methods

- Deliver pegRNA library and prime editor enzyme via transient transfection

- Allow sequential editing events to accumulate over desired timeframe [27]

Data Readout and Analysis:

- Amplify DNA Tape regions from cellular populations or single cells

- Perform next-generation sequencing to read accumulated symbols

- Decode event histories based on sequential symbol patterns [27]

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Genome Engineering

Table 3: Key Research Reagents for CRISPR Experimentation

| Reagent Category | Specific Examples | Function | Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas Expression Systems | pX330 (Addgene #42230), pX260 (Addgene #42229) [25] | Express Cas9 nuclease in mammalian cells | General genome editing, screening |

| sgRNA Cloning Vectors | pUC57-sgRNA (Addgene #51132), MLM3636 (Addgene #43860) [25] | Clone and express guide RNAs | Target-specific editing |

| Delivery Tools | Lipid nanoparticles (LNPs), Engineered VLPs, AAV vectors [28] [26] | Deliver editing components to cells | In vivo and therapeutic editing |

| Editing Enhancers | Alt-R HDR Enhancer Protein [26] | Improve homology-directed repair efficiency | Knock-in experiments, precise editing |

| Specialized Editors | PE2/PE3 systems (prime editing), ABE8e (base editing) [27] [26] | Enable advanced editing modalities | Specific mutation correction |

| Validation Tools | Next-generation sequencing, T7E1 assay, digital PCR | Confirm editing outcomes and assess off-target effects | Quality control, safety assessment |

Future Perspectives: Emerging Applications and Challenges

The CRISPR technology landscape continues to evolve rapidly, with several emerging trends and persistent challenges shaping its future development. The integration of artificial intelligence with CRISPR platform design is accelerating the identification of optimal guide RNAs and predicting editing outcomes with greater accuracy [26]. In 2025, Stanford researchers demonstrated that linking CRISPR tools with AI could significantly augment their capabilities, potentially reducing error rates and improving efficiency [24]. Companies like Algen Biotechnologies are developing AI-powered CRISPR platforms to reverse-engineer disease trajectories and identify therapeutic intervention points [26].

Delivery technologies remain a critical focus area, with ongoing efforts to expand tissue targeting beyond the liver and improve editing efficiency in therapeutically relevant cell types. Recent advances in tissue-specific lipid nanoparticles and engineered virus-like particles show promise for broadening the therapeutic applications of CRISPR [26]. The demonstrated ability to safely administer multiple doses of LNP-delivered CRISPR therapies opens new possibilities for treating chronic conditions [28].

Substantancial challenges remain in achieving equitable access to CRISPR-based therapies, with treatment costs ranging from $370,000 to $3.5 million per patient [29]. Addressing these disparities will require coordinated efforts including public-private partnerships, technology transfer initiatives, tiered pricing models, and open innovation frameworks [29]. Additionally, ethical considerations surrounding germline editing and appropriate regulatory frameworks continue to be debated within the scientific community and broader society [24] [29].

The expiration of key CRISPR patents in the coming years is expected to further democratize access to these technologies, potentially reducing costs and accelerating innovation [24]. As the field matures, the responsible development and application of CRISPR technologies will require ongoing dialogue between researchers, clinicians, patients, ethicists, and policymakers to ensure that the benefits of this revolutionary technology are widely shared.

The Modern Engineer's Toolkit: AI, Conjugates, and Cell Therapies in Action

The field of molecular engineering is undergoing a profound transformation, shifting from traditional rule-based design to a data-driven paradigm powered by generative artificial intelligence. The primary challenge in molecular design lies in efficiently exploring the immense chemical space, estimated to contain between 10^23 and 10^60 possible compounds [30]. Within this vast expanse, molecular scaffolds serve as the core framework in medicinal chemistry, guiding diversity assessment and scaffold hopping—a critical strategy for discovering new core structures while retaining biological activity [31]. Historically, approximately 70% of approved drugs have been based on known scaffolds, yet 98.6% of ring-based scaffolds in virtual libraries remain unvalidated [30]. This discrepancy highlights both the conservative nature of traditional drug discovery and the untapped potential for innovation.

Generative AI models—particularly Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Transformers—have emerged as transformative tools to address this challenge. These models learn the underlying probability distribution of existing chemical data to generate novel molecular structures with desired properties, enabling researchers to navigate chemical space with unprecedented efficiency [32]. By leveraging sophisticated molecular interaction modeling and property prediction, generative AI streamlines the discovery process, unlocking new possibilities in drug development and materials science [32]. This technological evolution represents a fundamental shift in molecular engineering research, moving from incremental modifications of known compounds to the de novo design of optimized molecular structures tailored to specific functional requirements.

Core Architectural Frameworks

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) for Molecular Representation

Variational Autoencoders employ a probabilistic encoder-decoder structure to learn continuous latent representations of molecular data. Unlike traditional autoencoders that compress input into a fixed latent representation, VAEs encode inputs as probability distributions, enabling them to generate novel samples by selecting points from this latent space [33].

The VAE architecture consists of two fundamental components:

- Encoder Network: The encoder input layer receives molecular features, typically as fingerprint vectors or SMILES strings. Hidden layers consist of fully connected units activated by a Rectified Linear Unit (ReLU), commonly configured with two to three hidden layers of 512 units each. The encoder transforms input data into parameters of a latent space distribution, generating the mean (μ) and log-variance (log σ²) that define this distribution [34].

- Decoder Network: The decoder takes a sample from the latent space and reconstructs it back into a molecular representation. Its architecture typically mirrors the encoder, with fully connected layers and ReLU activations, culminating in an output layer that generates molecular representations such as SMILES strings [34].

The VAE loss function combines reconstruction loss with Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence: ℒVAE = 𝔼qθ(z|x)[log pφ(x|z)] - D_KL[qθ(z|x) || p(z)] where the reconstruction loss measures the decoder's accuracy in reconstructing input from the latent space, and the KL divergence penalizes deviations between the learned latent distribution and a prior distribution p(z), typically a standard normal distribution [34].

For molecular design, VAEs are particularly valued for their ability to create smooth, continuous latent spaces where similar molecular structures cluster together, enabling efficient exploration and interpolation between compounds [32]. This characteristic makes them especially useful for scaffold hopping and molecular optimization tasks [31].

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) for Compound Generation

Generative Adversarial Networks operate on an adversarial training paradigm where two neural networks—a generator and a discriminator—compete in a minimax game. This framework has demonstrated remarkable capability in generating structurally diverse compounds with desirable pharmacological characteristics [34].

The GAN architecture for molecular design includes:

- Generator Network: The generator takes a random latent vector z as input and transforms it through fully connected networks with activation functions such as ReLU. The output layer produces molecular representations, effectively learning to map random noise to synthetically feasible molecular structures [34].

- Discriminator Network: The discriminator receives molecular representations and processes them through fully connected networks with activations like leaky ReLU. The output layer provides a probability indicating whether an input molecule is authentic (from the training data) or generated [34].

The adversarial training process is governed by two loss functions: Discriminator loss: ℒD = 𝔼z∼pdata(x)[log D(x)] + 𝔼z∼pz(z)[log(1 - D(G(z)))] Generator loss: ℒG = -𝔼z∼pz(z)[log D(G(z))] where G represents the generator network, D the discriminator network, pdata(x) the distribution of real molecules, and pz(z) the prior distribution of latent vectors [34].

While VAEs effectively capture latent molecular representations, they may generate overly smooth distributions that limit structural diversity. GANs complement this approach by introducing adversarial learning that enhances molecular variability, mitigates mode collapse, and generates novel chemically valid molecules [34]. This synergy ensures precise interaction modeling while optimizing both feature extraction and molecular diversity.

Transformer Architectures for Sequence-Based Molecular Design

Transformers, originally developed for natural language processing, have been successfully adapted for molecular design by treating molecular representations such as SMILES strings as a specialized chemical language [31]. The transformer's attention mechanism enables it to capture complex long-range dependencies in molecular data, making it particularly effective for understanding intricate structural relationships.

Key components of transformer architecture for molecular applications include:

- Self-Attention Mechanism: This allows the model to weigh the importance of different parts of a molecular sequence when generating new representations. For each token in a sequence, self-attention computes a weighted sum of all other tokens, enabling the model to capture global molecular context [33].

- Multi-Head Attention: By employing multiple attention heads in parallel, transformers can simultaneously focus on different molecular substructures and functional groups, capturing various aspects of chemical significance [32].

- Positional Encoding: Since transformers process sequences in parallel rather than sequentially, positional encodings provide information about the relative positions of atoms or tokens in the molecular sequence [32].

Transformers excel at learning subtle dependencies in data, which is particularly valuable for capturing the complex relationships between molecular structure and properties [32]. Their parallelizable architecture enables efficient processing of large chemical datasets, reducing training time compared to sequential models [33].

Comparative Analysis of Architectural Performance

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Generative AI Architectures for Molecular Design

| Feature | VAEs | GANs | Transformers |

|---|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Encoder-decoder with probabilistic latent space | Generator-discriminator with adversarial training | Encoder-decoder with self-attention mechanisms [33] |

| Mathematical Foundation | Variational inference, Bayesian framework [33] | Game theory, Nash equilibrium [33] | Linear algebra, self-attention, multi-head attention [33] |

| Sample Quality | May produce blurrier outputs but with meaningful interpolation [33] [35] | Sharp, high-quality samples [33] | High-quality, coherent sequences [33] |

| Output Diversity | Less prone to mode collapse, better coverage of data distribution [33] | Can experience mode collapse, reducing variability [33] | Generates contextually relevant, diverse outputs [33] |

| Training Stability | Generally more stable training process [33] [35] | Often unstable, requires careful hyperparameter tuning [33] | Stable with sufficient data and resources [36] |

| Primary Molecular Applications | Data compression, anomaly detection, feature learning [33] | Image synthesis, style transfer, molecular generation [33] | Natural language processing, sequence-based molecular generation [33] |

| Latent Space | Explicit, often modeled as Gaussian distribution [33] | Implicit, typically using random noise as input [33] | Implicit, depends on context [33] |

Table 2: Performance Metrics of Hybrid Generative Models in Drug Discovery

| Model | Architecture | Key Application | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| VGAN-DTI | Combination of GANs, VAEs, and MLPs | Drug-target interaction prediction | 96% accuracy, 95% precision, 94% recall, 94% F1 score [34] |

| TGVAE | Integration of Transformer, GNN, and VAE | Molecular generation for drug discovery | Generates larger collection of diverse molecules, discovers previously unexplored structures [37] |

| GraphAF | Autoregressive flow-based model with RL fine-tuning | Molecular property optimization | Efficient sampling with targeted optimization toward desired molecular properties [32] |

| GCPN | Graph convolutional policy network with RL | Molecular generation with targeted properties | Generates molecules with desired chemical properties while ensuring high chemical validity [32] |

Advanced Hybrid Frameworks and Experimental Protocols

VGAN-DTI Framework for Drug-Target Interaction Prediction

The VGAN-DTI framework represents a sophisticated integration of generative models with predictive components for enhanced drug-target interaction prediction. This hybrid approach addresses the critical need for accurate DTI prediction in early-stage drug discovery, where traditional methods often struggle with the complexity and scale of biochemical data [34].

Experimental Protocol:

- Data Preparation: The model is trained on molecular datasets such as BindingDB, with compounds represented as SMILES strings or molecular fingerprints.

- VAE Component: The VAE encodes molecular structures into a latent distribution, learning continuous representations that capture essential chemical features. The encoder processes molecular features as fingerprint vectors through hidden layers with 512 ReLU-activated units. The latent space layer generates mean (μ) and log-variance (log σ²) parameters.

- GAN Component: The generator network creates synthetic molecular structures from random noise, while the discriminator evaluates their authenticity against real molecular data. This adversarial process enhances the diversity and realism of generated compounds.

- MLP Integration: A multilayer perceptron processes the generated molecular features along with target protein information to predict binding affinities and interaction probabilities. The MLP typically includes three hidden layers with nonlinear activation functions and a sigmoid output layer for classification [34].

- Training Procedure: The framework undergoes iterative training where the VAE and GAN components are optimized jointly, followed by MLP training on the generated features. The loss function combines VAE reconstruction loss, KL divergence, GAN generator and discriminator losses, and MLP classification loss.

This framework demonstrates how combining the strengths of VAEs for representation learning and GANs for diversity generation can significantly enhance predictive performance in critical drug discovery tasks [34].

Transformer-Graph VAE for Molecular Generation

The Transformer-Graph Variational Autoencoder represents a cutting-edge approach that combines multiple advanced architectures to address limitations in traditional molecular generation methods [37].

Experimental Protocol:

- Molecular Representation: Instead of relying solely on SMILES strings, TGVAE employs molecular graphs as input data, which more effectively captures complex structural relationships within molecules [37].

- Graph Neural Network Integration: GNNs process the molecular graph structure, learning representations that capture atomic interactions and bond patterns.

- Transformer Component: The transformer architecture processes the graph-derived representations using self-attention mechanisms to capture long-range dependencies and global molecular context.

- VAE Framework: The model encodes the processed representations into a latent distribution, then decodes samples from this distribution to generate novel molecular structures.

- Technical Challenges Addressed: The framework specifically addresses common issues like over-smoothing in GNN training and posterior collapse in VAEs to ensure robust training and improve the generation of chemically valid and diverse molecular structures [37].

This hybrid approach has demonstrated superior performance compared to existing methods, generating a larger collection of diverse molecules and discovering structures previously unexplored in chemical databases [37].

Visualization of Architectures and Workflows

VAE-GAN Hybrid Molecular Design Workflow

Diagram 1: VAE-GAN Hybrid Molecular Design Workflow

Transformer-Graph VAE Architecture

Diagram 2: Transformer-Graph VAE Architecture

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for AI-Driven Molecular Design

| Resource | Type | Function/Application | Examples/Specifications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Datasets | Data | Training and validation of generative models | BindingDB [34], ChEMBL, PubChem |

| Molecular Representations | Computational Format | Encoding chemical structures for AI processing | SMILES [31], SELFIES, Molecular Graphs [37], Fingerprints [34] |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | Software | Implementing and training generative models | TensorFlow, PyTorch, JAX |

| Chemical Validation Tools | Software/Analytical | Assessing chemical validity and properties | RDKit, OpenBabel, Chemical Feasibility Checkers |

| High-Performance Computing (HPC) | Hardware | Training complex generative models | GPU Clusters, Cloud Computing Resources |

| Property Prediction Models | Software | Evaluating generated molecules | QSAR Models, Docking Simulations [32] |

| Benchmarking Platforms | Software | Standardized performance evaluation | MOSES, GuacaMol |

Optimization Strategies for Enhanced Molecular Design

Property-Guided Generation and Multi-Objective Optimization

Property-guided generation represents a significant advancement in molecular design, enabling researchers to direct the generative process toward molecules with specific desirable characteristics. The Guided Diffusion for Inverse Molecular Design (GaUDI) framework exemplifies this approach, combining an equivariant graph neural network for property prediction with a generative diffusion model. This integration has demonstrated remarkable efficacy in designing molecules for organic electronic applications, achieving 100% validity in generated structures while optimizing for both single and multiple objectives [32].

Similarly, VAEs have been successfully adapted for property-guided generation through the integration of property prediction directly into the latent representation. This approach allows for more targeted exploration of molecular structures with desired properties by navigating the continuous latent space toward regions associated with specific molecular characteristics [32]. The probabilistic nature of VAEs enables efficient exploration of the chemical space while maintaining synthetic feasibility, making them particularly valuable for inverse molecular design problems where target properties are known but optimal molecular structures are unknown.

Reinforcement Learning for Molecular Optimization

Reinforcement learning has emerged as a powerful strategy for optimizing molecular structures toward desired chemical properties. In this paradigm, an agent learns to make sequential decisions about molecular modifications, receiving rewards based on how well the resulting structures meet target objectives such as drug-likeness, binding affinity, and synthetic accessibility [32].

Key RL approaches in molecular design include:

- Molecular Deep Q-Networks (MolDQN): This approach modifies molecules iteratively using rewards that integrate multiple properties, sometimes incorporating penalties to preserve similarity to a reference structure [32].

- Graph Convolutional Policy Network (GCPN): This model uses RL to sequentially add atoms and bonds, constructing novel molecules with targeted properties. The GCPN has demonstrated remarkable results in generating molecules with desired chemical characteristics while ensuring high chemical validity [32].

- DeepGraphMolGen: This framework employs a graph convolution policy with a multi-objective reward to generate molecules with strong binding affinity to specific targets while minimizing off-target interactions, illustrating the effectiveness of RL in complex molecular optimization tasks [32].

A critical challenge in RL-based molecular design is balancing exploration of new chemical spaces with exploitation of known promising regions. Techniques such as Bayesian neural networks for uncertainty estimation and randomized value functions help maintain this balance, preventing premature convergence to suboptimal solutions [32].

Bayesian Optimization in Latent Space

Bayesian optimization provides a powerful framework for molecular design, particularly when dealing with expensive-to-evaluate objective functions such as docking simulations or quantum chemical calculations [32]. This approach builds a probabilistic model of the objective function and uses it to make informed decisions about which candidate molecules to evaluate next.