Ensuring Reliability in Computational Biology: A Comprehensive Guide to Molecular Simulation Validation

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a critical step for ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of computational studies in drug development and biomedical research.

Ensuring Reliability in Computational Biology: A Comprehensive Guide to Molecular Simulation Validation

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive framework for validating molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, a critical step for ensuring the reliability and reproducibility of computational studies in drug development and biomedical research. It addresses the foundational principles of validation, explores practical methodological protocols and quality assurance measures, outlines strategies for troubleshooting and optimizing simulation quality, and discusses advanced techniques for comparing results with experimental data. Aimed at researchers and scientists, this guide synthesizes current best practices to help the community enhance the physical validity and scientific impact of simulation-based findings.

Why Validation Matters: The Core Principles of Reliable Molecular Simulation

In molecular simulation research, validation is the process of establishing credibility, but it rests on two distinct pillars: physical validity and model accuracy. Understanding this distinction is fundamental for producing reliable, reproducible research.

Physical validity concerns whether a simulation correctly samples from a physically realistic ensemble. It asks: "Is my simulation obeying the fundamental laws of statistical mechanics and producing physically plausible behavior?" [1]

Model accuracy concerns how well the simulation's results match specific experimental observations for a particular system. It asks: "Does my chosen force field and model correctly reproduce the real-world data?" [2] [3]

A simulation can be physically valid yet inaccurate (proper sampling with an imperfect model), or physically invalid yet accidentally match some experimental data (faulty sampling that happens to produce a plausible result). Rigorous research requires establishing both.

Core Concepts: Definitions and Diagnostic Framework

What is the fundamental difference between physical validity and model accuracy?

The table below contrasts these two core concepts.

Table 1: Distinguishing Physical Validity from Model Accuracy

| Aspect | Physical Validity | Model Accuracy |

|---|---|---|

| Core Question | Is the simulation sampling correctly according to statistical mechanics? | Does the model's output match experimental reality? |

| Primary Concern | Correctness of the sampling protocol and numerical methods [1] | Appropriateness of the force field parameters and physical model [2] [3] |

| Validated Against | Theoretical distributions and physical laws (e.g., Boltzmann distribution) [1] | Experimental data (e.g., scattering profiles, folding rates, densities) [2] [3] |

| Common Issues | Incorrect integrators, non-conservative dynamics, poor thermostatting, lack of ergodicity [1] | Imperfect force field parameters, inadequate water models, missing electronic polarization [2] [4] |

| Diagnostic Methods | Energy fluctuation tests, kinetic distribution checks, ensemble validation [1] | Comparison with NMR data, X-ray scattering, protein folding rates, bilayer properties [2] [3] [4] |

How do I diagnose a physically invalid simulation?

Physically invalid simulations often manifest through specific numerical and statistical signatures. The following diagnostic workflow helps identify where the physical validity is breaking down.

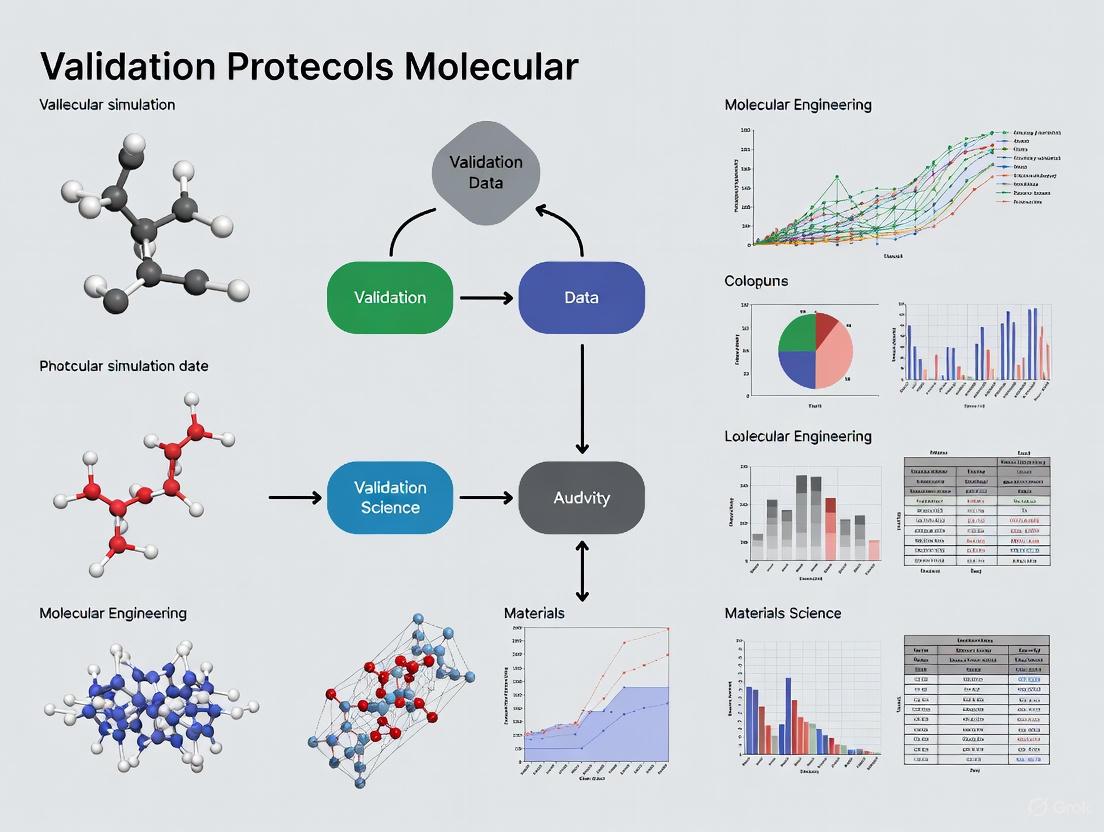

Figure 1: A diagnostic workflow for identifying common sources of physical invalidity in molecular simulations, based on statistical tests of simulation output [1].

How do I validate my simulation against experimental data?

Validating a model against experimental data requires careful comparison with relevant, high-quality experimental observables. The table below outlines key experimental comparison points and the metrics used for validation.

Table 2: Experimental Validation Metrics for Common System Types

| System Type | Experimental Observable | Simulation Metric | Validation Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Proteins (General) | NMR chemical shifts, J-couplings, NOEs [5] [4] | Backbone dihedral angles, side-chain rotamer distributions | Time-averaged comparison with experimental measurements [4] |

| Membrane Proteins / Lipid Bilayers | X-ray/neutron scattering structure factors, bilayer thickness [2] | Transbilayer electron density profile, area per lipid | Fourier reconstruction of simulated density profiles for direct comparison [2] |

| Protein Folding | Folding rates, free energy landscapes, native state stability [3] | Folding/unfolding timescales, free energy calculations | Comparison of simulated rates with stopped-flow or FRET experiments [3] |

| Structural Dynamics | SAXS curves, FRET distances, B-factors [5] | Radius of gyration, inter-residue distances, crystallographic B-factors | Calculation of theoretical SAXS curves or B-factors from trajectory [5] |

Troubleshooting Common Validation Failures

My simulation fails physical validity tests. What are the most common causes?

The following FAQ addresses frequent sources of physical invalidity and their solutions.

Table 3: Troubleshooting Physical Validity Failures

| Problem Symptom | Potential Root Cause | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Non-conservation of energy in NVE simulations [1] | Incorrect integrator, broken constraints, potential/force discontinuity | Use verified symplectic integrators (e.g., velocity Verlet), check constraint algorithms, ensure potential smoothness |

| Kinetic energy distribution does not match expected Gamma distribution [1] | Incorrect thermostat implementation, "flying ice cube" effect (energy drain from solute) | Use thermostats with correct canonical sampling, avoid separate thermostats for solute/solvent [1] |

| Truncation of electrostatic interactions causing artifactual ordering [1] | Using cutoffs instead of mesh-based Ewald methods for long-range electrostatics | Switch to Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) for all electrostatic calculations [1] |

| Unphysical water flow through nanotubes or channels [1] | Use of charge-group cutoffs, insufficient pairlist buffers | Disable charge-group cutoffs, increase pairlist update frequency or buffer size |

| pdb2gmx errors: "Residue not found in database," "Long bonds/missing atoms" [6] | Force field mismatch, incomplete structure file, incorrect atom naming | Verify force field compatibility, complete missing atoms before simulation, use -ignh for hydrogen handling [6] |

| grompp errors: "Invalid order for directive," "Atom index out of bounds" [6] | Incorrect topology file organization, position restraint file issues | Follow proper topology directive order, ensure position restraints match molecule order [6] |

My simulation is physically valid but fails experimental validation. Where should I look?

When physical validity is established but experimental agreement is poor, the issue typically lies with the physical model or sampling.

Figure 2: A systematic approach to diagnosing the root causes of failed experimental validation when physical validity is confirmed [2] [5] [4].

Experimental Protocols for Systematic Validation

Protocol: Validating a Lipid Bilayer Simulation Against Diffraction Data

This protocol outlines the method for comparing simulated lipid bilayers with experimental diffraction data, as pioneered in the validation of DOPC bilayers [2].

Purpose: To quantitatively validate a simulated lipid bilayer structure by comparing with X-ray and neutron diffraction data.

Principle: Instead of comparing binned electron density profiles (which are method-dependent), this approach compares simulation and experiment in reciprocal space via structure factors, then reconstructs real-space profiles using the same Fourier analysis applied to experimental data [2].

Procedure:

- Run production simulation of the lipid bilayer (e.g., DOPC at 66% RH, 5.4 waters/lipid) for sufficient time to ensure equilibration (typically >50 ns for united-atom bilayers).

- Extract structure factors from the simulation trajectory by:

- Calculating the continuous Fourier transform F(s) of the transbilayer scattering-length density

- Sampling F(s) at the experimental Bragg positions (s = h/d)

- Compute experimental standard deviation of both simulated and experimental structure factors to establish uncertainty bounds.

- Perform Fourier reconstruction using the discrete structure factors to generate the overall transbilayer scattering-density profile.

- Compare key structural parameters: bilayer thickness (DB), area per lipid, and widths of terminal methyl distributions.

Validation Criteria: Simulated structure factors and reconstructed profiles should fall within experimental error for all measured harmonics. Particular attention should be paid to the terminal methyl distribution width, which has shown significant force-field dependence in previous validation studies [2].

Protocol: Testing Physical Validity Through Integrator and Thermostat Validation

This protocol provides specific tests to verify that a simulation is sampling the correct physical ensemble [1].

Purpose: To verify that the simulation numerical methods and protocols are producing physically valid sampling.

Principle: Symplectic integrators sample a "shadow Hamiltonian" rather than the true Hamiltonian, with predictable relationships between timestep and energy fluctuations. Similarly, thermostatted simulations should produce correct kinetic energy distributions [1].

Procedure:

- Energy fluctuation test:

- Run multiple short NVE simulations with different timesteps (e.g., 1 fs and 2 fs)

- Calculate the standard deviation of total energy fluctuations for each

- Verify that σ(H(Δt₁))/σ(H(Δt₂)) ≈ Δt₁²/Δt₂² [1]

- Kinetic energy distribution test:

- Run an NVT simulation at the target temperature

- Collect kinetic energy values throughout the trajectory

- Fit the distribution to a gamma distribution and compare with theoretical expectation

- Ergodicity test:

- Run multiple independent simulations from different initial conditions

- Compare property averages across all simulations

- Verify that within-simulation averages match across-simulation averages

Validation Criteria: Energy fluctuations should scale quadratically with timestep, kinetic energy should follow the expected Gamma distribution, and different simulation replicates should yield statistically equivalent averages [1].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 4: Key Software and Validation Tools for Molecular Simulations

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function | Validation Application |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physical-Validation Python Library [1] | Analysis library | Provides standardized tests for physical validity | Testing energy conservation, kinetic distributions, and ensemble correctness |

| GROMACS Simulation Package [1] [4] [6] | MD simulation software | High-performance molecular dynamics | Production simulations with built-in physical validation suite |

| AMBER, NAMD, ilmm [4] | MD simulation software | Alternative simulation packages | Cross-package validation and force field comparison studies |

| CHARMM36, AMBER ff99SB-ILDN [2] [4] | Force fields | Empirical molecular mechanics parameters | Testing model accuracy across different force fields |

| PMC Repository | Literature database | Access to scientific literature on validation | Methodological reference and comparison with prior validation studies |

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

> Sampling Limitations

FAQ: Why is my simulation trapped in a non-functional conformational state? Biological molecules have rough energy landscapes with many local minima separated by high-energy barriers. In conventional Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, the system can easily become trapped in one of these minima, preventing the sampling of all conformations relevant to biological function [7] [8]. This poor sampling leads to an incomplete characterization of the protein's dynamic behavior.

FAQ: Which enhanced sampling method should I choose for my system? The choice of method depends on your system's biological and physical characteristics, particularly its size [7]. The table below summarizes the primary enhanced sampling techniques and their recommended applications.

Table: Enhanced Sampling Techniques Comparison

| Method | Key Principle | Best For | Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) [7] [8] | Parallel simulations at different temperatures exchange states, enabling a random walk in temperature space. | Systems with less rugged energy landscapes; studying folding and free energy landscapes. | Efficiency sensitive to the choice of maximum temperature; requires many replicas, increasing computational cost. |

| Metadynamics [7] [8] | "Fills" free energy wells with a bias potential to discourage revisiting previous states. | Systems where ergodicity is broken; studying protein folding, conformational changes, and ligand binding. | Requires careful selection of a small number of collective variables (CVs) to describe the process of interest. |

| Simulated Annealing [7] | System temperature is gradually decreased from a high value to explore the energy landscape. | Characterizing very flexible systems and large macromolecular complexes at a relatively low computational cost. | Inspired by metallurgy annealing; includes variants like Generalized Simulated Annealing (GSA). |

Troubleshooting Protocol: Implementing a Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) Simulation

- Objective: Enhance conformational sampling for a small protein or peptide.

- Workflow:

- Replica Setup: Decide on the number of replicas and the range of temperatures. The highest temperature should be high enough to allow barriers to be crossed, but not so high that it harms efficiency [7].

- Simulation: Run parallel MD simulations for each replica at its assigned temperature.

- Exchange Attempts: Periodically attempt to swap the configurations of adjacent replicas based on a Metropolis criterion using their potential energies and temperatures [7].

- Analysis: Analyze the combined trajectory from all temperatures, reweighting as necessary, to compute thermodynamic and kinetic properties.

The following workflow diagram outlines the core REMD process.

> Force Field Inaccuracies

FAQ: Are modern molecular force fields still inaccurate? Yes, force fields are simplified models and therefore have inherent limitations and inaccuracies. Although they have been slowly improving and are generally reliable for many systems, errors can still occur in the calculation of bonded and non-bonded interactions, which can impact protein stability and the accuracy of your model [9]. As a scientist, you must understand these limitations to interpret your results correctly [9].

FAQ: What is a known issue with force fields and how can it be identified? Some force fields have been shown to over-stabilize helical structures in peptides compared to experimental NMR data for unfolded states [10]. This can be identified by comparing scalar couplings (J-couplings) from simulation trajectories against experimental NMR data using Karplus relations [10].

Table: Force Field Validation Against Experimental Data

| Force Field | Unweighted α-Helical Population for Ala5 | Agreement with NMR (χ²) | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amber03 | 33.0% | 1.8 (DFT1) | Used protonated termini; population reduced to ~11% after reweighting [10]. |

| Gromos53a6 | 13.5% | 1.8 (DFT1) | Lower inherent helical propensity; showed good agreement before reweighting [10]. |

| CHARMM27/cmap | 41.5% | 2.0 (DFT1) | Higher helical content; required reweighting to match experimental data [10]. |

Troubleshooting Protocol: Validating Force Field Parameters with NMR J-Couplings

- Objective: Assess the backbone conformational sampling of a peptide from an MD simulation.

- Workflow:

- Simulation: Run an all-atom MD simulation of your peptide in explicit solvent.

- Trajectory Analysis: For each frame of the trajectory, calculate the backbone dihedral angles (φ, ψ).

- J-Coupling Calculation: Compute scalar couplings (e.g., ³JHNHα) from the dihedral angles using an appropriate Karplus relation [10].

- Comparison: Compare the time-averaged J-couplings from the simulation with experimental NMR values. A high χ² value indicates poor agreement and potential force field bias [10].

- Reweighting (Optional): If a bias is found, the trajectory can be reweighted to determine the populations of α-, β-, and polyproline II regions that best match the experimental data [10].

> Trajectory Analysis

FAQ: How can errors in trajectory data affect my analysis? Measurement or processing errors in trajectory data can corrupt vehicle dynamics and resulting distributions of kinematic quantities [11]. When used for model calibration, these errors can have a significant impact on the fitted parameters and, consequently, on the outcomes of subsequent simulations [11].

FAQ: What can be done about inaccurate trajectory data? A "traffic-informed" methodology can be used to reconstruct microscopic traffic data [11]. This involves identifying and replacing extremely biased fragments of a trajectory with synthetic data that is consistent with both vehicle kinematics and overall traffic dynamics, thereby restoring physical consistency [11].

Troubleshooting Protocol: A Framework for Validating Traffic Simulation Models

- Objective: Quantitatively assess the ability of a traffic simulation model to reproduce a real-world scenario.

- Workflow:

- Data Preparation: Obtain a ground-truth dataset, such as the NGSIM vehicle trajectories. Apply a reconstruction filter if necessary to improve data quality [11].

- Model Calibration: Calibrate your microscopic models (e.g., car-following like IDM, lane-changing like MOBIL) against the ground-truth data [11].

- Multi-Scale Validation:

- Microscopic Validation: Compare simulated vehicle kinematics (speed, acceleration, spacing) against the ground-truth data [11].

- Macroscopic Validation: Compare emergent macroscopic patterns (e.g., flow, density, speed relationships) from the simulation against those derived from the ground-truth data [11].

- Impact Assessment: Quantify the propagation of errors by comparing results from models calibrated against raw versus reconstructed data [11].

The diagram below illustrates this multi-scale validation framework.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Molecular Simulation

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| AMBER [7] | A suite of biomolecular simulation programs. | Performing MD simulations and enhanced sampling methods like REMD. |

| GROMACS [7] [9] | A molecular dynamics package for simulating Newtonian equations of motion. | High-performance MD simulation; includes implementations of methods like metadynamics. |

| NAMD [7] | A parallel molecular dynamics code designed for high-performance simulation. | Simulating large biomolecular systems and complexes. |

| NGSIM Datasets [11] | A library of detailed vehicle trajectory data. | Serving as a ground-truth for calibrating and validating microscopic traffic models. |

| Karplus Relations [10] | Empirical equations that relate NMR scalar couplings to molecular geometry. | Validating the conformational sampling of force fields against experimental data. |

FAQs: Core Concepts and Initial Setup

Q1: What are the fundamental pillars of a robust molecular simulation validation protocol? A robust validation protocol stands on three core pillars: Sampling Verification, Physical Validity, and Experimental Connection. This involves demonstrating that your simulations are sufficiently long, sample from the correct thermodynamic ensemble, and that their results can be meaningfully compared against experimental data [5].

Q2: Why is demonstrating convergence critical, and how can I check for it? Convergence is critical because without it, the calculated properties may not be statistically meaningful or representative of the system's true behavior. A simulation result is compromised if it has not been shown to be converged [5]. You should:

- Perform multiple independent simulations (at least 3) starting from different initial configurations [5].

- Conduct time-course analysis (e.g., block averaging) to show that the property of interest has stabilized and is independent of the simulation's starting point [5].

- Clearly state how the simulation was split into equilibration and production phases, and specify the amount of production data used for analysis [5].

Q3: How do I choose between an all-atom and a coarse-grained model for my system? The choice depends on your research question and the required balance between model accuracy and computational cost. You must justify that the "chosen model, resolution, and force field are accurate enough to answer the specific question" [5]. All-atom models are typically used for detailed studies of specific interactions, while coarse-grained models allow for the simulation of larger systems and longer timescales [12].

Q4: What key information must be documented during system setup to ensure reproducibility? To enable others to reproduce your work, you must provide a detailed account of your system setup [5]. The table below summarizes the essential parameters to document.

Table: Essential System Setup Parameters for Reproducibility

| Parameter Category | Specific Details to Report |

|---|---|

| System Composition | Simulation box dimensions, total number of atoms, number and type of water molecules, salt concentration, lipid composition (if applicable) [5]. |

| Force Field & Model | Force field name and version, water model, protonation states of residues, and any custom parameters [5]. |

| Simulation Parameters | Non-bonded cutoff distance, thermostat and barostat types and coupling constants, integration timestep [5]. |

| Software & Code | Simulation and analysis software names and versions. Any custom code or scripts used [5]. |

| Data Availability | Initial coordinate files, final output files, and simulation input/parameter files, provided via supplementary information or a public repository [5]. |

FAQs: Troubleshooting Sampling and Physical Validity

Q5: My simulation results are erratic. How can I verify the physical validity of my simulation parameters?

Use the open-source Python package physical_validation to perform automated tests on your simulation data [13]. This package can detect unphysical artifacts by checking for:

- The correct distribution of the kinetic energy.

- The equipartition of kinetic energy across all degrees of freedom in the system.

- Whether the system samples the correct thermodynamic ensemble for configurational properties.

- The numerical precision and convergence of the integrator [13]. These tests can identify issues arising from poor parameter choices, incompatible models, or even software bugs [13].

Q6: I suspect my simulation is trapped in a local energy state. What can I do? If the event you are studying occurs on a timescale longer than what is practical for standard molecular dynamics, you may need enhanced sampling methods [5]. Before switching methods, first confirm the lack of sampling by running multiple independent simulations from different starting points. If enhanced sampling is needed, you must clearly state all parameters and convergence criteria used for the chosen method in your manuscript [5].

Q7: How can I use high-throughput simulations to improve my validation pipeline? High-throughput molecular dynamics can be used to generate large, consistent datasets for validating methods and machine learning models [14]. By running thousands of simulations under a consistent protocol, you can rigorously benchmark prediction methods and build robust, generalizable models for properties like density, heat of vaporization, and enthalpy of mixing [14]. This approach ensures that your validation is not based on a handful of potentially non-representative examples.

FAQs: Data Management and Comparison with Experiment

Q8: What are the FAIR principles, and why are they important for my simulation data? FAIR stands for Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable [15]. Adhering to these principles is crucial because it moves the field beyond data being "left forgotten on personal computers," which hinders reproducibility and prevents the reuse of valuable data for training AI or designing new experiments [15]. Making data FAIR amplifies its impact and helps build a sustainable ecosystem for computational science.

Q9: What is the best way to compare my simulation results with experimental data? The most meaningful comparisons are for experimentally accessible properties that provide a direct link to your simulation's biological or chemical context. You should provide calculations that connect to experiments, such as [5]:

- Binding affinities from assays.

- NMR chemical shifts or J-couplings.

- SAXS curves.

- FRET distances.

- Structure factors and diffusion coefficients. The discussion should focus on the physiological relevance of your results in the context of existing experimental data [5].

Q10: Are there automated tools to help with the entire validation workflow? Yes, the field is moving towards integrated, automated pipelines. For instance, Automated Machine Learning Pipelines (AMLP) are now being developed that unify the workflow from dataset creation to model validation, sometimes even employing AI agents to assist with tasks like code selection and input preparation [16]. Commercial platforms also offer integrated tools that combine physics-based simulations with machine learning for accelerated property prediction and validation [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Resolving Sampling and Convergence Issues

A common and critical problem is the lack of convergence in simulated properties, which can lead to incorrect conclusions.

Table: Symptoms and Solutions for Sampling Issues

| Symptoms | Potential Causes | Corrective Actions |

|---|---|---|

| Property of interest (e.g., energy, RMSD) has not plateaued. | Insufficient simulation time; trapped in a local energy minimum. | Extend simulation time; run multiple independent replicas from different starting structures [5]. |

| High variance in results between replicas. | Poor sampling of the full conformational space. | Increase the number of independent simulations (aim for ≥3). Consider enhanced sampling methods if the timescale of the event is beyond brute-force MD [5]. |

| Erratic or unphysical energy drift. | Incorrect equilibration; system instability. | Re-check equilibration protocol. Use physical_validation to check integrator precision and kinetic energy distributions [13]. |

Guide 2: Addressing Physical Validity and Force Field Problems

Sometimes, simulations run without crashing but produce unphysical results due to model or parameter issues.

Table: Diagnosing Physical Validity Problems

| Unphysical Result | Diagnostic Tool/Action | Solution |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect ensemble averages (e.g., pressure, density). | Use physical_validation ensemble validation tests [13]. |

Verify barostat/thermostat settings; check force field compatibility with the simulated conditions. |

| Poor energy equipartition. | Use physical_validation kinetic energy equipartition check [13]. |

Review the use of constraints (e.g., bond, angle) and the assigned masses of atoms. |

| System instability (e.g., protein unfolds). | Check simulation logs for high forces. | Verify protonation states; ensure the force field is appropriate for your system (e.g., proteins, membranes) [5] [12]. |

| Property predictions disagree with experiment. | Validate simulation protocol on a system with known experimental results first [14]. | Re-evaluate method choice (force field, water model); confirm sufficient sampling. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Software

Table: Key Software and Data Resources for a Validation Pipeline

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

physical_validation [13] |

Python Package | Performs automated tests for physical validity (kinetic energy, equipartition, ensemble sampling). |

| MDDB (Molecular Dynamics Data Bank) [15] | Database | A proposed FAIR-compliant repository for storing and sharing simulation data, enabling reuse and validation. |

| AMLP (Automated ML Pipeline) [16] | Computational Pipeline | Unifies workflow from dataset creation to model validation; uses LLM agents for code selection and setup. |

| GROMACS [13] | Simulation Software | A leading MD package that integrates with physical_validation for end-to-end code testing. |

| FAIR Principles [15] | Data Management Framework | A set of guidelines to make data Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, and Reusable, crucial for reproducibility. |

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: My simulation shows an unrealistic continuous flow of water molecules. What could be the cause?

This is a known artifact often traced to the use of inappropriate cutoffs for non-bonded interactions. Using charge-group cutoffs or generating pair lists without sufficient buffers can induce such unphysical flow. Switching to Particle Mesh Ewald (PME) for long-range electrostatics and ensuring your pair list update frequency (nstlist) is appropriate typically resolves this issue [18].

Q2: Why is my protein or DNA fragment not folding correctly, despite using standard parameters? Inaccurate treatment of non-bonded interaction cutoffs, particularly with reaction-field methods, can significantly affect biomolecular folding. Truncating electrostatic interactions can alter the free energy landscape. It is recommended to use PME for electrostatic calculations and to validate your cutoff parameters against known folded structures [18].

Q3: My simulation exhibits a 'flying ice cube' effect, where kinetic energy seems to drain from internal vibrations into global translation. What's wrong? This effect is a classic symptom of a poorly configured thermostat. Some thermostats can fail to maintain a proper kinetic energy distribution across all degrees of freedom, causing the internal motions of molecules to "cool down" while the center-of-mass motion "heats up." Using a modern thermostat that correctly couples to internal degrees of freedom and avoiding the separate coupling of solute and solvent to different heat baths can mitigate this problem [18].

Q4: How can I be sure my chosen integration time step is not making my simulation unstable? A time step that is too large can lead to inaccurate integration of the equations of motion and cause a simulation to "blow up." A key validation test is to run two short, identical simulations at different time steps (e.g., 1 fs and 2 fs) and compare the fluctuations in total energy. For a symplectic integrator, the ratio of these fluctuations should be proportional to the square of the ratio of the time steps. A deviation from this expectation indicates a problem with the integration protocol [18].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Instabilities and Energy Drift in Integrators

Symptoms: Simulation crashes (e.g., "Bonds blowing up") or a steady, unphysical drift in the total energy of a constant-energy (NVE) simulation.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Check Your Time Step (

dt): The time step is often the primary culprit. The fastest motions in the system (typically bond vibrations involving hydrogen atoms) dictate the maximum stable time step. A value that is too large will cause the integrator to become unstable.- Solution: Reduce the time step. For all-atom simulations, 2 fs is common. To use a larger time step (e.g., 4 fs), you must constrain these fast-moving bonds.

Validate Your Constraint Algorithm: To allow for a larger time step, constraints are applied to freeze the fastest bond vibrations. An inaccurate constraint algorithm will cause energy drift.

- Solution: Use robust constraint algorithms like LINCS or SHAKE. The

constraintsmdp option should be set toall-bondsorh-bondsto remove these high-frequency degrees of freedom [12].

- Solution: Use robust constraint algorithms like LINCS or SHAKE. The

Perform an Integrator Validation Test: This test checks if your simulation is sampling the expected "shadow Hamiltonian," which is a sign of a correct and stable integration [18].

- Protocol:

a. Run two short, independent NVE simulations from the same initial configuration, using different time steps (e.g., 1 fs and 2 fs).

b. Calculate the fluctuation (standard deviation) of the total energy for each run.

c. The ratio of the fluctuations should satisfy the following equation:

Fluctuation_Δt2 / Fluctuation_Δt1 ≈ (Δt2 / Δt1)²d. A significant deviation from this expected ratio indicates a problem with your integrator setup, such as discontinuities in the potential energy function or imprecise constraints.

- Protocol:

a. Run two short, independent NVE simulations from the same initial configuration, using different time steps (e.g., 1 fs and 2 fs).

b. Calculate the fluctuation (standard deviation) of the total energy for each run.

c. The ratio of the fluctuations should satisfy the following equation:

Issue 2: Unphysical System Behavior from Incorrect Parameters

Symptoms: Incorrect density, unrealistic ordering of lipid bilayers, altered diffusion rates, or spurious flow effects.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Non-bonded Interaction Cutoffs: Truncating van der Waals and, especially, electrostatic interactions is a major source of error. It can artificially enhance ordering in lipid bilayers and affect biomolecular folding [18].

- Solution: Always use a state-of-the-art long-range electrostatics method like Particle Mesh Ewald (PME). For van der Waals interactions, use a Verlet cutoff scheme with a modern dispersion correction.

Thermostat Coupling: The choice of thermostat can profoundly impact the dynamics and structural properties of your system. A weak coupling thermostat like Berendsen does not generate a correct canonical (NVT) ensemble.

- Solution: Use a stochastic thermostat (e.g.,

integrator = sdin GROMACS) or a Nosé-Hoover thermostat for correct canonical sampling. The friction coefficient (tau-t) for stochastic dynamics should be chosen carefully (e.g., 2 ps for water) [19]. Avoid coupling different groups (solute and solvent) to separate thermostats, as this can artificially slow down dynamics [18].

- Solution: Use a stochastic thermostat (e.g.,

Validate the Physical Parameters:

- Protocol: A simple yet powerful test is to simulate a well-characterized reference substance, such as pure water (SPC/E, TIP3P, etc.), under standard conditions (e.g., 300 K, 1 bar). After equilibration, properties like density, potential energy, and diffusion constant should match established literature values for your chosen force field. A failure to reproduce these basic properties indicates a problem with your parameter set or simulation protocol.

Issue 3: Artifacts from Boundary Condition Implementation

Symptoms: Unphysical density variations at the box edges, system instability, or abnormal pressure readings.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

Box Size and Solvation: A box that is too small can cause a molecule to interact with its own periodic image, leading to artificial correlations and stabilization of incorrect conformations.

- Solution: Ensure the box size is large enough so that the shortest distance between any atom in the solute and its periodic image is at least twice the longest non-bonded cutoff distance.

Pressure Coupling (Barostat): Incorrect barostat settings can cause the box size to oscillate wildly or collapse.

- Solution: Use a semi-isotropic or anisotropic barostat for membrane simulations. The coupling time constant (

tau-p) should be chosen with care; a value that is too small can cause instabilities. Thecompressibilitymust be set correctly for your system (e.g., ~4.5e-5 bar⁻¹ for water).

- Solution: Use a semi-isotropic or anisotropic barostat for membrane simulations. The coupling time constant (

Experimental Validation Protocols

Protocol 1: Energy Fluctuation Test for Integrator Validation [18]

- Objective: To verify that the numerical integrator is sampling a physically correct shadow Hamiltonian.

- Methodology:

- Prepare an initial system configuration (e.g., a solvated protein).

- Run two separate, short (e.g., 50-100 ps) simulations in the NVE (microcanonical) ensemble from the same initial state.

- Use two different integration time steps (e.g.,

dt1 = 1 fsanddt2 = 2 fs). All other parameters must be identical. - Output the total energy at a high frequency (e.g., every step).

- Analysis:

- For each trajectory, calculate the standard deviation of the total energy (σ(E₁) and σ(E₂)).

- Compute the ratio of the fluctuations:

R = σ(E₂) / σ(E₁). - Compute the expected ratio:

R_expected = (dt2 / dt1)². - Compare R to R_expected. Agreement within a reasonable margin (e.g., 10-20%) suggests a physically valid integration. Significant deviation indicates a problem.

Protocol 2: Ensemble Validation Test [18]

- Objective: To ensure the simulation correctly samples the intended thermodynamic ensemble (e.g., NVT or NPT).

- Methodology:

- Perform multiple (at least 3) independent simulations of the same system, starting from different initial configurations (e.g., different initial velocities).

- Run each simulation for the same length of time under the same conditions (thermostat/barostat, temperature, pressure).

- Analysis:

- Calculate key thermodynamic properties (e.g., potential energy, density, radius of gyration of a protein) from each trajectory.

- Perform statistical analysis (e.g., compute the average and standard deviation across the independent runs).

- The properties should be consistent across all runs. Large discrepancies or systematic drifts indicate a lack of convergence or an issue with the sampling method.

Essential Simulation Parameter Tables

Table 1: Common Integrators and Their Typical Use Cases

Integrator (integrator) |

Algorithm Type | Best Use Cases | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

md |

Leap-frog | Standard production MD | Efficient, sufficient for most cases. Kinetic energy is slightly off [19]. |

md-vv |

Velocity Verlet | High-accuracy NVE; Nose-Hoover/Parrinello-Rahman coupling | More accurate than leap-frog, but higher computational cost [19]. |

sd |

Stochastic Dynamics | Efficient thermostating | Acts as a thermostat and integrator. Use tau-t ~2 ps for water [19]. |

bd |

Brownian Dynamics | Overdamped systems (e.g., implicit solvent) | Euler integrator for position Langevin dynamics [19]. |

Table 2: Recommended Parameters for Accurate Physical Behavior

| Parameter Category | Incorrect Setting (Leads to Error) | Recommended Setting | Rationale |

|---|---|---|---|

| Electrostatics | Cut-off (coulombtype = Cut-off) |

coulombtype = PME |

Correctly handles long-range forces without truncation artifacts [18]. |

Time Step (dt) |

2 fs with no H-bond constraints | 2 fs with constraints = h-bonds |

Allows a stable 2 fs step by removing fastest vibrations [12]. |

| Thermostat | Berendsen; separate solute/solvent baths | Stochastic (sd) or Nose-Hoover |

Generates a correct canonical ensemble [18]. |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents

Table 3: Essential Software and Validation Tools

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Physical-Validation Python Library [18] | A suite of tests to check for physical correctness of simulations. | Detects common errors like non-conservative integrators and deviations from the Boltzmann ensemble. |

GROMACS mdp Options [19] |

The input parameter file defining all aspects of the simulation. | Critical for defining integrator, cutoffs, thermostats, barostats, and other core parameters. |

| Multiple Time Stepping (MTS) [19] | An integrator that evaluates slow forces less frequently. | Can improve computational efficiency but requires careful setup of mts-level2-forces and mts-level2-factor. |

Workflow Diagram: Simulation Validation Protocol

Building a Robust Workflow: Protocols and Quality Assurance for Biomolecular Simulations

This guide provides standard setup protocols for Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, a crucial tool for understanding the behavior of biomolecules at an atomic level. The procedure involves multiple steps to transform a static protein structure into a dynamic, solvated system ready for simulation. The following sections outline the key steps, supported by detailed workflows and troubleshooting advice, to ensure robust and reproducible simulation data for your research.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

The table below lists the essential components required to set up and run a molecular dynamics simulation.

| Item Name | Type | Function / Description |

|---|---|---|

| Protein Structure File (PDB) | Data File | The initial 3D atomic coordinates of the biomolecule, typically obtained from the RCSB Protein Data Bank [20] [21]. |

| GROMACS | Software Suite | A robust, open-source software package for performing MD simulations and analyzing the results [20] [22]. |

| Force Field | Parameter Set | A set of mathematical functions and parameters that describe the potential energy of the system and define interatomic interactions (e.g., ffG53A7) [20] [22]. |

| CHARMM-GUI | Web Server | An online tool that simplifies the process of building complex simulation systems, especially membrane proteins [23] [24]. |

| Water Model | Solvent Model | A representation of water molecules used to solvate the protein and mimic an aqueous physiological environment (e.g., TIP3P) [24]. |

| Ions (Na+/Cl-) | System Component | Counterions added to the system to neutralize its net electric charge and simulate a specific ionic concentration [20] [22]. |

| Lipids | System Component | For membrane protein simulations, lipids are used to create a bilayer that mimics the protein's native environment [23]. |

Core Protocol: From PDB to Production Run

The following diagram illustrates the primary workflow for setting up and running a molecular dynamics simulation.

Step 1: System Preparation

The first stage involves building the simulation system from the initial protein structure.

- A. Obtain and Pre-format the Protein Structure: Download your protein of interest in PDB format from the RCSB database [25] [20]. Visually inspect the structure using a molecular viewer. Pre-formatting is critical: remove crystallographic water molecules and separate any ligand coordinates from the main protein file, as their chemistry needs to be defined separately [20].

- B. Generate Topology and Select Force Field: Use a tool like

pdb2gmxin GROMACS to convert the PDB file into GROMACS-specific formats (.grofor coordinates,.topfor topology). This step adds missing hydrogen atoms and prompts you to select an appropriate force field (e.g.,ffG53A7for proteins with explicit solvent) [20]. - C. Define the Simulation Box and Solvate: Place the protein in a simulation box (e.g., cubic, dodecahedron) with Periodic Boundary Conditions (PBC) to avoid edge effects. A common command is

editconf -f protein.gro -o protein_editconf.gro -bt cubic -d 1.4 -c. Then, solvate the box using thesolvatecommand, which adds water molecules and updates the topology file [20] [22]. - D. Neutralize the System: Add counterions (e.g.,

Na+,Cl-) to neutralize the system's net charge using thegenioncommand. This requires first generating a pre-processed input file (.tpr) withgrompp[20] [22].

Step 2: Energy Minimization

Energy minimization relieves any steric clashes or unrealistic geometry introduced during the setup process. It adjusts atomic coordinates to find a low potential energy state using methods like steepest descent [22]. This step produces an energy-minimized structure as the starting point for the equilibration phase.

Step 3: System Equilibration

In this phase, the system is brought to a stable thermodynamic state. This is typically done in two sub-stages [22]:

- NVT Equilibration: A short simulation is run with a constant Number of particles, Volume, and Temperature (NVT ensemble). This allows the temperature of the system to stabilize.

- NPT Equilibration: A subsequent simulation is run with a constant Number of particles, Pressure, and Temperature (NPT ensemble). This allows the density of the system to stabilize, which is crucial as most real-world experiments are conducted at constant pressure.

Monitor the Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD); once it fluctuates around a constant value, the system is considered equilibrated and ready for production [22].

Step 4: Production Run

The production run is the final, extended simulation from which data is collected for analysis. It is performed using the same NPT ensemble as the second equilibration step. The resulting trajectory file captures the motion of all atoms over time and is the primary data source for analyzing the system's structural and dynamic properties [22].

Frequently Asked Questions and Troubleshooting

What are the most common file formats in an MD simulation, and what are they for?

The table below summarizes the key file formats used in a GROMACS MD workflow.

| File Extension | Format Type | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| .pdb | Structure File | Initial input; contains atomic coordinates from the Protein Data Bank [20] [26]. |

| .gro | Structure File | GROMACS format for molecular structure coordinates; can also act as a trajectory file [20] [26]. |

| .top | Topology File | System topology describing the molecule, including atoms, bonds, force field parameters, and charges [20] [27]. |

| .tpr | Run Input File | Portable binary file containing the complete simulation setup (topology, parameters, coordinates) [26]. |

| .xtc/.trr | Trajectory File | Store atomic positions (and velocities/forces) over time from the production run for analysis [26]. |

| .edr | Energy File | Contains time series of energies, temperature, pressure, and density recorded during the simulation [26]. |

My simulation failed during thegromppstep. What should I check?

The grompp step pre-processes the topology, coordinates, and parameters into a single input file. Failures here are often due to:

- Topology Mismatch: Ensure the atom count in your topology (

.top) file matches the number in your coordinate (.groor.pdb) file. Inconsistent numbers indicate a problem in the system building steps [20]. - Parameter Issues: Check that all parameters for bonds, angles, and dihedrals are defined in your chosen force field, especially for non-standard residues or ligands [20] [27].

- File Paths: If you are using include topology (

.itp) files for molecules like ligands, verify that the file paths in your main topology file are correct.

How do I prepare a membrane protein for simulation?

Preparing a membrane protein requires embedding it in a lipid bilayer. The CHARMM-GUI web server (specifically its Membrane Builder module) is the recommended tool as it automates this complex process [23].

- Procedure: Input your PDB ID. The server can download a pre-oriented structure from the OPM database. You can then select the protein chain, manipulate termini, define disulfide bonds, and—most importantly—select a lipid composition that mimics the native membrane [23].

- Key Step: CHARMM-GUI will orient the protein correctly in the membrane (with the Z-axis as the membrane normal) and assemble the lipids, water, and ions around it, providing all necessary files for simulations in GROMACS and other software [23].

This guide provides troubleshooting and methodological support for researchers engaged in molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, framed within the essential context of validation protocols for computational data research. The selection of an appropriate force field and software suite is a critical determinant of simulation accuracy and reliability, particularly in drug discovery applications where predicting molecular behavior is paramount [28].

FAQs: Force Field Selection and Methodology

What is the fundamental difference between a traditional Molecular Mechanics Force Field (MMFF) and a Machine Learning Force Field (MLFF)?

Answer: Traditional MMFFs and MLFFs represent two distinct approaches to modeling the potential energy surface (PES) of a molecular system [28].

Molecular Mechanics Force Fields (MMFFs): These use a fixed analytical form to approximate the energy landscape. The PES is decomposed into bonded (bonds, angles, torsions) and non-bonded (electrostatics, dispersion) interactions [28]. Examples include Amber, GAFF, and OPLS [28].

Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs): These map atomistic features and coordinates to the PES using neural networks without being limited by a fixed functional form [28].

What are the key considerations when validating a newly parameterized force field?

Answer: Validation is crucial to ensure a force field's predictive power. Key performance benchmarks include [28]:

- Geometries: Accuracy in predicting relaxed molecular structures and geometries.

- Torsional Energy Profiles: Quality of torsion parameters, as they significantly affect conformational distribution.

- Conformational Energies and Forces: Accuracy in calculating energies and forces for different molecular conformations.

A well-validated force field should demonstrate state-of-the-art performance across these diverse benchmarks to ensure expansive chemical space coverage and reliability for computational drug discovery [28].

Our simulations are yielding unexpected conformational distributions. Where should we focus our troubleshooting?

Answer: Unexpected conformational distributions most frequently stem from inaccuracies in the torsional energy profiles. The quality of torsion parameters is a major factor influencing the conformational distribution of small molecules, which in turn impacts critical properties like protein-ligand binding affinity prediction [28]. You should:

- Benchmark Torsional Profiles: Compare the force field's torsional energy predictions against high-quality quantum mechanics (QM) data for key dihedral angles in your molecule.

- Review Parameterization Data: Examine the scope and diversity of the torsion profiles used to train the force field. Models like ByteFF, trained on millions of torsion profiles, are designed to mitigate this issue [28].

- Check for Chemical Environment Transferability: Ensure the force field can accurately handle the specific chemical environments (e.g., unique functional groups) present in your molecule.

How do data-driven force fields like ByteFF address the limitations of traditional look-up table approaches?

Answer: Traditional look-up table approaches face significant challenges with the rapid expansion of synthetically accessible chemical space [28]. Data-driven force fields address this by:

- Utilizing Expansive Datasets: They are trained on large-scale, highly diverse QM datasets. For example, ByteFF was trained on 2.4 million optimized molecular fragment geometries and 3.2 million torsion profiles [28].

- Employing Graph Neural Networks (GNNs): GNNs predict force field parameters directly from molecular structure, preserving molecular symmetry and permutational invariance, which enhances transferability and scalability [28].

- Covering Expansive Chemical Space: This modern approach allows for accurate parameter prediction across a broader range of drug-like molecules, moving beyond the constraints of pre-determined lists or patterns [28].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Poor Prediction of Molecular Geometries

Symptoms: Optimized molecular structures deviate significantly from experimental crystal structures or high-level QM calculations.

Resolution Protocol:

- Validate on Benchmark Set: Test the force field on a small set of molecules with known, reliable geometries.

- Check Bond and Angle Parameters: Investigate the equilibrium values (r₀, θ₀) and force constants (kᵣ, kθ) for the specific chemical bonds and angles involved. The force field's accuracy in predicting these parameters is critical [28].

- Review Training Data: Determine if the force field was trained on a dataset that includes optimized geometries with analytical Hessian matrices, as this is essential for learning accurate bonded parameters [28].

- Consider a Different Force Field: If inaccuracies persist, switch to a force field known for superior performance on relaxed geometry benchmarks [28].

Issue: Inaccurate Calculation of Interaction Energies

Symptoms: Protein-ligand binding affinities or intermolecular interaction energies are inconsistent with experimental isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR) data.

Resolution Protocol:

- Focus on Non-Bonded Parameters: Scrutinize the van der Waals (σ, ε) and partial charge (q) parameters.

- Verify Charge Conservation: Ensure the summation of partial charges in a molecule equals its net charge; a failure here indicates a fundamental parameterization error [28].

- Assess Electrostatic Model: Evaluate the method used for assigning partial charges (e.g., RESP, AM1-BCC). Consider if a more advanced electrostatic model is required.

- Cross-Validate with Ab Initio Methods: Compare the force field's non-bonded interaction energies with those from QM calculations for a representative dimer complex.

Experimental Protocols for Force Field Validation

Protocol 1: Benchmarking Torsional Energy Profiles

Objective: To validate the accuracy of a force field in reproducing torsional energy landscapes against quantum mechanics reference data.

Methodology:

- Select Target Dihedrals: Identify the central rotatable bond(s) of interest within the test molecule.

- Generate QM Reference: Perform a relaxed torsion scan at a consistent QM level of theory (e.g., B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP) [28]. Rotate the dihedral angle in increments (e.g., 15°), optimizing all other degrees of freedom at each step. Record the single-point energy at each optimized geometry.

- Perform Molecular Mechanics (MM) Calculation: Execute the same torsion scan using the force field under validation, ensuring no additional geometry optimization is performed on the MM-minimized structure.

- Analyze Discrepancies: Calculate the root-mean-square error (RMSE) between the QM and MM energy profiles. Investigate any regions of significant deviation (>1 kcal/mol).

Protocol 2: Validating Conformational Energy Ranking

Objective: To assess the force field's ability to correctly rank the relative energies of different low-energy conformers.

Methodology:

- Conformer Generation: Use software (e.g., RDKit, OMEGA) to generate an ensemble of low-energy conformers for a flexible test molecule.

- QM Single-Point Calculations: Calculate the single-point energy for each conformer at a high-level QM theory to establish the "ground truth" energy ranking.

- MM Energy Evaluation: Evaluate the potential energy of each conformer using the force field being tested.

- Statistical Comparison: Compute Spearman's rank correlation coefficient between the QM and MM energy rankings. A coefficient close to 1.0 indicates high fidelity in conformational ranking.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details key computational tools and data used in the development and validation of modern force fields as described in the research [28].

| Reagent/Resource | Function in Force Field Development |

|---|---|

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) Datasets | Provides high-accuracy reference data (energies, forces, geometries) for training and validating force field parameters [28]. |

| Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Machine learning models that predict molecular mechanics parameters directly from molecular structures, preserving symmetry [28]. |

| Fragmentation Algorithms | Cleaves large molecules into smaller, manageable fragments while preserving local chemical environments for efficient QM data generation [28]. |

| SMILES/SMARTS Strings | Line notation and patterns for representing molecular structures and chemical environments in computational workflows [28]. |

| Hessian Matrices | Matrix of second derivatives of energy with respect to atomic coordinates; used in training for accurate vibrational frequency prediction [28]. |

Workflow Diagrams

Force Field Development and Validation

Frequently Asked Questions

FAQ 1: Why does my simulation get trapped in unphysical energy minima, and how can I resolve this?

This is a common sign that the simulation is non-ergodic, meaning it fails to sample the complete potential energy surface (PES). Standard Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations at low temperatures can remain trapped in local minima, unable to cross energy barriers, which restricts the exploration of the full conformational landscape [29]. This broken ergodicity compromises both kinetic and thermodynamic predictions [29]. To resolve this:

- Implement Enhanced Sampling: Use methods like parallel tempering (replica exchange) to help the simulation overcome energy barriers [29].

- Validate with Kinetic Transition Networks (KTNs): Compare your simulation's discovered minima and transition states against a reference KTN, if available for your molecule. This provides a ground truth for the global landscape [29].

- Inspect the Force Field: Be aware that force field inaccuracies can create spurious stable structures that do not exist on the true PES. Data augmentation with configurations from known pathways can improve the model's accuracy [29].

FAQ 2: How can I check if my simulated conformational ensemble is accurate and representative?

Accurate ensembles are crucial for predicting experimental observables, especially for flexible molecules like Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) [30]. You can check your ensemble's quality by:

- Comparing to Experimental Data: Calculate ensemble-averaged experimental observables (e.g., NMR chemical shifts, J-couplings) from your simulation and compare them directly to laboratory measurements [30].

- Using Maximum Entropy Reweighting: If the simulation samples a wide range of conformations but with incorrect weights, apply a posteriori reweighting methods. These techniques adjust the statistical weights of conformations in your ensemble to achieve better agreement with experimental data without generating new structures [30].

- Ensuring Adequate Sampling: Reweighting methods require that the initial simulation has already sampled all the relevant conformations. If it hasn't, reweighting will fail, indicating a need for longer or enhanced sampling simulations [30].

FAQ 3: My simulation conserves energy, but the results do not match experimental kinetics. What is wrong?

Energy conservation is a necessary but insufficient check for kinetic accuracy. Your model might accurately reflect energies and forces near minima but misrepresent the transition states and barriers that govern reaction rates [29]. To diagnose this:

- Benchmark Against Transition States: Use a dataset like Landscape17 that provides reference transition states and pathways. Test if your model can correctly identify these saddle points on the PES [29].

- Evaluate the Global Landscape: Current Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) can show excellent local energy conservation but still miss over half of the true transition states and generate unphysical stable structures. A comprehensive benchmark of the entire kinetic network is required [29].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Simulation Shows Broken Ergodicity

Description: The simulation is stuck in a subset of conformational states and cannot explore the entire thermodynamic ensemble, leading to biased results.

Solution Steps:

- Confirm the Problem: Calculate the root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) of your structures over time. If it plateaus at a low value and never increases, it suggests trapping. Alternatively, use a reference KTN to see if known minima are missing [29].

- Choose an Enhanced Sampling Method: Select a method suited to your system and goal. Common choices include:

- Validate with a Known Network: After running the enhanced sampling simulation, validate the resulting ensemble against a reference KTN or a set of experimental observables to ensure all relevant states have been found [29] [30].

Problem: Force Field Leads to Unphysical Minima

Description: The molecular model (force field or MLIP) exhibits stable structures that are not present on the true, high-fidelity potential energy surface.

Solution Steps:

- Identify Spurious Minima: Perform a global landscape exploration on a small, representative system using your model. Compare the discovered minima to those from a high-level theoretical method (e.g., hybrid-DFT) or experimental data. Minima that exist only in your model are likely unphysical [29].

- Augment Training Data: If using an MLIP, retrain the model by adding configurations from known pathways (e.g., from approximate steepest-descent paths between minima and transition states) to the training dataset [29].

- Conduct a Landscape Benchmark: Systematically test the refined model on a benchmark like Landscape17. A successful model should reproduce the reference minima and transition states while minimizing spurious ones [29].

Experimental Protocols & Data

Protocol 1: Validating a Kinetic Transition Network

Purpose: To benchmark a molecular model's ability to reproduce the global kinetics of a system by comparing its predicted kinetic transition network (KTN) to a reference calculation.

Methodology:

- Acquire a Reference KTN: Use a pre-computed KTN for your molecule, such as those provided in the Landscape17 dataset for small organic molecules [29].

- Explore the Model's Landscape: Using your molecular model (e.g., a force field or MLIP), perform a global landscape exploration. This typically involves:

- Compare Stationary Points: Quantitatively compare the energies and geometries of the minima and transition states found by your model against the reference.

- Calculate Global Metrics: Determine key metrics such as the percentage of reference transition states recovered and the number of spurious minima generated by your model [29].

Protocol 2: Refining an Ensemble with Experimental Data

Purpose: To correct the statistical weights of a pre-sampled conformational ensemble to achieve better agreement with experimental observables.

Methodology:

- Run a Broad Sampling Simulation: Perform a long MD simulation or use enhanced sampling to generate a diverse set of conformations that covers the relevant conformational space [30].

- Select Experimental Observables: Choose one or more ensemble-averaged experimental observables for refinement, such as NMR chemical shifts or J-coupling constants [30].

- Apply a Maximum Entropy Reweighting Method: Use an algorithm to optimize the weights of each conformation in your ensemble. The goal is to maximize the entropy of the ensemble (keeping it as broad as possible) while minimizing the discrepancy between the calculated and experimental ensemble averages [30].

- Validate on Independent Data: Check the refined ensemble against an experimental observable that was not used in the reweighting process. Good agreement indicates a successful and transferable refinement [30].

Table 1: Quantitative Benchmarks for ML Potentials on Landscape17

This table summarizes the performance of state-of-the-art machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) when tested on the Landscape17 benchmark, revealing common challenges. The "Reference" data is from hybrid-level DFT calculations [29].

| Molecule | Reference Minima | Reference Transition States | Typical MLIP Performance: Missing TS | Typical MLIP Performance: Spurious Minima |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ethanol | 2 | 2 | >50% missed | Present |

| Malonaldehyde | 2 | 4 | >50% missed | Present |

| Salicylic Acid | 7 | 11 | >50% missed | Present |

| Aspirin | 11 | 37 | >50% missed | Present |

| Improvement Strategy | Data augmentation with pathway configurations [29] | Landscape benchmarking and model retraining [29] |

Table 2: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

This table lists key computational tools and datasets used for validation in molecular simulations.

| Item Name | Function / Explanation |

|---|---|

| Landscape17 Dataset [29] | A public dataset providing complete Kinetic Transition Networks (minima, transition states, and pathways) for several small molecules, serving as a benchmark for validating kinetic properties. |

| Kinetic Transition Network (KTN) [29] | A graph-based representation of a molecule's potential energy surface, where nodes are minima and edges are transition states. It is essential for testing global kinetics and ergodicity. |

| Maximum Entropy Reweighting Methods [30] | A class of algorithms that adjust the weights of conformations in a simulated ensemble to improve agreement with experimental data while keeping the ensemble as unbiased as possible. |

| Enhanced Sampling Algorithms (e.g., Parallel Tempering) [29] [12] | Simulation techniques designed to overcome energy barriers and facilitate ergodic sampling by modifying the underlying Hamiltonian or temperature. |

| TopSearch Package [29] | An open-source Python package specifically designed for exploring molecular energy landscapes and finding minima and transition states. |

Workflow Diagrams

In molecular simulation research, reporting a result without its associated uncertainty is akin to providing a destination without indicating the distance; the information is of limited use for making informed decisions. The quantitative assessment of uncertainty and sampling quality is essential because molecular systems are highly complex and often at the very edge of current computational capabilities [31]. Consequently, modelers must analyze and communicate statistical uncertainties so that "consumers" of simulated data—be it other researchers, collaborating experts in drug development, or regulatory scientists—can accurately understand the significance and limitations of the reported findings [31] [32].

The core of this practice lies in distinguishing between a mere report and a true prediction. A report states that "we did X, followed by Y, and got Z." A prediction, however, provides an estimate Z along with a confidence interval, thereby enabling others to gauge its reliability and reproducibility [33]. This is not just an academic formality; the practical consequences of neglecting uncertainty can be severe, as illustrated by historical cases where unheeded error bars led to critical misunderstandings and substantial real-world costs [33]. This guide provides a foundational framework for integrating robust uncertainty quantification into your molecular simulation workflow, ensuring your results are both statistically sound and scientifically actionable.

Statistical Foundations: Key Definitions and Concepts

A clear understanding of statistical terminology is a prerequisite for proper uncertainty quantification. The following definitions, aligned with the International Vocabulary of Metrology (VIM), form the essential lexicon for researchers in this field [31].

Table 1: Essential Statistical Terms for Uncertainty Quantification

| Term | Definition & Formula | Key Interpretation for Researchers |

|---|---|---|

| Expectation Value (〈x〉) | The true average of a random quantity x over its probability distribution, P(x). For continuous variables: ( \langle x \rangle = \int dx P(x)x ) [31] |

The idealized "true value" your simulation aims to estimate. It is typically unknown. |

| Arithmetic Mean ((\bar{x})) | The estimate of the expectation value from a finite sample: ( \bar{x} = \frac{1}{n}\sum{j=1}^{n}xj ) [31] | Your "best guess" of the true value based on your n data points. |

| Variance ((\sigma_x^2)) | A measure of the fluctuation of a random quantity: ( \sigma_x^2 = \int dx P(x)(x - \langle x \rangle)^2 ) [31] | The inherent spread of the data around the true mean. |

| Standard Deviation ((\sigma_x)) | The positive square root of the variance [31]. | The typical width of the distribution of x. Not a direct measure of uncertainty in the mean. |

| Experimental Standard Deviation ((s(x))) | An estimate of the true standard deviation from a sample: ( s(x) = \sqrt{\frac{\sum{j=1}^{n}(xj - \bar{x})^2}{n-1}} ) [31] | The sample standard deviation, quantifying the spread of your observed data. |

| Standard Uncertainty | Uncertainty in a result expressed as a standard deviation [31]. | The fundamental expression of uncertainty for a measured or calculated value. |

| Experimental Standard Deviation of the Mean ((s(\bar{x}))) | The estimate of the standard deviation of the distribution of the mean: ( s(\bar{x}) = \frac{s(x)}{\sqrt{n}} ) [31] | The "standard error," directly quantifying the uncertainty in your estimated mean. |

A critical concept that underpins these definitions is the Central Limit Theorem (CLT). The CLT states that the average of a sample drawn from any distribution will itself follow a Gaussian distribution, becoming more Gaussian as the sample size increases [33]. This is why the Gaussian (or "normal") distribution is so pervasive in error analysis. It assures us that the mean of our simulation data—be it energies, distances, or rates—will be distributed in a way that allows us to use the well-defined tools of Gaussian statistics to assign confidence intervals, provided we have sufficient sampling [33].

Experimental Protocols: A Workflow for Uncertainty Analysis

Implementing a tiered approach to computational modeling prevents wasted resources and ensures the statistical reliability of your final results. The following workflow, depicted in the diagram below, outlines this process.

Workflow Title: UQ in Molecular Simulation

Phase 1: Pre-simulation Planning and Feasibility Checks

Before expending computational resources, perform initial checks to determine the project's viability [31]. This includes estimating the expected signal magnitude, the computational cost required to achieve a target precision, and whether the chosen method and model are appropriate for the scientific question.

Phase 2: Running Simulations and Data Collection

Execute your molecular dynamics (MD) or Monte Carlo (MC) simulations, ensuring that trajectory data and relevant observables are saved at a frequency that captures their fluctuations without creating storage bottlenecks [31] [34]. For enhanced sampling techniques, careful planning is required, as these methods can introduce complex correlation structures that complicate uncertainty analysis [35].

Phase 3: Semi-quantitative Sampling Quality Checks

Before calculating final uncertainties, diagnose the quality of your sampling. Key diagnostic tools include:

- Autocorrelation Analysis: Calculate the autocorrelation time (τ) of your data to understand how many steps are required to obtain statistically independent samples [31] [35]. This is crucial for avoiding overconfidence in correlated data.

- Effective Sample Size (ESS): Estimate the effective number of independent samples, which is less than the total number of data points in a correlated trajectory. ESS can be estimated via autocorrelation analysis or block averaging methods [35].

- Convergence Testing: Monitor the evolution of computed observables over time. A stable running average is a good indicator, but it should be supplemented with other metrics like the behavior of multiple independent simulation runs [36].

Phase 4: Estimation of Observables and Uncertainties

Once sampling quality is confirmed, proceed to calculate the quantities of interest and their uncertainties.

- Calculate the Arithmetic Mean: Compute the sample mean ((\bar{x})) as your best estimate of the observable [31].

- Compute the Standard Error: Calculate the experimental standard deviation of the mean ((s(\bar{x}))) [31]. For correlated data, use the effective sample size (ESS) in the denominator: ( s(\bar{x}) \approx \frac{s(x)}{\sqrt{ESS}} ) [31].

- Construct Confidence Intervals (CIs): The most recommended practice is to report 95% confidence intervals [35]. For a sufficiently large sample size (n > 30), a 95% CI is approximately: ( \bar{x} \pm 1.96 \times s(\bar{x}) ). For smaller samples, the multiplier comes from the Student's t-distribution with ( n-1 ) degrees of freedom [33].

Troubleshooting Common Issues in Uncertainty Quantification

FAQ 1: My error bars are so large that the result is inconclusive. What went wrong? This typically indicates inadequate sampling. Your simulation may not have run long enough to explore the relevant conformational space fully, leading to high variance in the observables [36].

- Solution: Extend simulation time. If computationally prohibitive, consider running multiple independent, shorter simulations (replicates) starting from different initial conditions. The variance between the means of these replicates provides a direct estimate of uncertainty [36]. Also, investigate enhanced sampling techniques to overcome energy barriers more efficiently.

FAQ 2: How do I handle uncertainty when comparing two computational methods? A common mistake is to assume two methods are equivalent if their 95% confidence intervals overlap. This is statistically incorrect [37].

- Solution: You must calculate the confidence interval for the difference between the methods. If the errors of methods A and B are independent, the variance of the difference is ( \text{Var}(A-B) = \text{Var}(A) + \text{Var}(B) ). However, if A and B are tested on the same set of systems (highly likely), their errors are correlated. In this case, use a paired t-test or calculate the variance of the per-system differences: ( \text{Var}(A-B) = \frac{1}{N-1}\sum{i=1}^{N}[(Ai - B_i) - (\overline{A-B})]^2 ) [37]. The diagram below illustrates this logic.

Workflow Title: Method Comparison Logic

FAQ 3: How do I report uncertainty for non-Gaussian or derived quantities like free energies? Quantities like free energies (from alchemical transformations or umbrella sampling) or probabilities often have asymmetric error bars [33] [37].

- Solution: Use bootstrapping or non-parametric statistics [33] [37]. Bootstrapping involves randomly resampling your dataset with replacement thousands of times, recalculating the quantity of interest each time. The distribution of these bootstrap estimates directly provides a confidence interval, which can be asymmetric (e.g., the 2.5th and 97.5th percentiles form a 95% CI) [33].

FAQ 4: My simulation box size seems to be affecting the result. Is this a real effect or a sampling artifact? Claims of simulation box size effects on thermodynamics have often been shown to disappear with increased sampling, highlighting the danger of underpowered simulations [36].

- Solution: Conduct a statistical significance test. If you observe an apparent trend with box size, run multiple replicates (e.g., 20) for each box size and plot the results with 95% confidence intervals [36]. A true physical effect will show a statistically significant trend across box sizes, while a sampling artifact will show overlapping confidence intervals and no consistent trend.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for Statistical Analysis

Table 2: Key "Research Reagent Solutions" for Uncertainty Quantification

| Tool / "Reagent" | Function & Purpose | Example Use Case in Molecular Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| Block Averaging Method | Estimates the standard error of the mean for correlated time-series data by analyzing the variance of block averages of increasing size. | Determining the uncertainty in the average potential energy from an MD trajectory where frames are highly correlated [31] [35]. |

| Autocorrelation Function | Quantifies the correlation between data points at different time intervals, used to calculate correlation times and effective sample size. | Diagnosing slow conformational dynamics in a protein simulation by analyzing the autocorrelation of a dihedral angle [31]. |

| Bootstrap Resampling | A non-parametric method for estimating the sampling distribution of a statistic (e.g., median, AUC) and its confidence interval. | Calculating an asymmetric confidence interval for a binding free energy calculated via umbrella sampling [33] [37]. |

| Student's t-Distribution | Provides the correct multiplier for constructing confidence intervals when the population standard deviation is unknown and the sample size is small. | Reporting a 95% CI for the diffusion coefficient of a lipid from three independent 1-microsecond simulations [33]. |