Enhancing Molecular Dynamics Simulation Accuracy: Advanced Force Fields, Sampling, and Machine Learning for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on improving the accuracy of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations.

Enhancing Molecular Dynamics Simulation Accuracy: Advanced Force Fields, Sampling, and Machine Learning for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on improving the accuracy of Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations. It explores foundational concepts of force fields and energy functions, details advanced methodologies like enhanced sampling and machine learning interatomic potentials, and offers practical strategies for troubleshooting and optimization. The content further covers rigorous validation techniques and comparative benchmarking against experimental and quantum mechanical data, synthesizing these elements to highlight their collective impact on accelerating and improving the reliability of biomedical research.

Understanding the Core Components: Force Fields and Energy Landscapes in MD Simulations

The Role and Functional Form of Modern Force Fields

Frequently Asked Questions

1. What is the fundamental functional form of a modern classical force field?

Modern classical force fields calculate the total potential energy of a system as a sum of bonded and non-bonded interaction terms. The most common form, used by AMBER and CHARMM families, is expressed as:

[ E = \sum{\text{bonds}} kr(r - r0)^2 + \sum{\text{angles}} k\theta(\theta - \theta0)^2 + \sum{\text{dihedrals}} \frac{Vn}{2} [1 + \cos(n\phi - \gamma)] + \sum{i

The bonded terms include harmonic potentials for bond stretching and angle bending, and periodic functions for torsional rotations. The non-bonded terms consist of Lennard-Jones potential for van der Waals interactions and Coulomb's law for electrostatics [1] [2].

2. My DNA simulations show unrealistic structural distortions. What could be the cause and solution?

This is a known issue in nucleic acids simulations. Traditional force fields like AMBER's parm99 exhibited severe DNA double helix distortions due to inaccurate dihedral parameters [2]. Two main solutions have been developed:

- Use updated dihedral parameters: The ol-series (ol15, ol21) and bsc1 force fields correct these inaccuracies by refining dihedral parameters based on quantum mechanical calculations [2].

- Address non-bonded interactions: Consider the CUFIX correction for Lennard-Jones parameters, which improves DNA-protein interactions and sliding diffusion constants by two orders of magnitude [2].

3. How do I choose the correct combination rules for my force field in GROMACS?

The combining rules for Lennard-Jones interactions are force field-specific and must be set correctly in your simulation parameters [1]:

Table: Force Field Combination Rules in GROMACS

| Force Field | comb-rule | Description |

|---|---|---|

| GROMOS | 1 | Geometric mean for both C12 and C6 |

| CHARMM, AMBER | 2 | Lorentz-Berthelot rules |

| OPLS | 3 | Geometric mean for both σ and ε |

In GROMACS, these are specified in the forcefield.itp file's [defaults] section under the comb-rule column [1].

4. Are there modern approaches to overcome traditional force field limitations?

Yes, several advanced methods address fundamental force field limitations:

- Polarizable force fields: Models like AMOEBA, CHARMM-Drude, and OPLS5 incorporate electronic polarization using inducible point dipoles or Drude oscillators for more accurate electrostatic interactions [1] [3].

- Machine-learned force fields: Approaches like sGDML can construct force fields from high-level ab initio calculations, potentially achieving coupled-cluster (CCSD(T)) level accuracy for small molecules [4].

- Automated parameterization: Tools like ForceBalance systematically optimize parameters against experimental and quantum mechanical reference data, improving reproducibility and accuracy [5].

5. Why does my water model poorly reproduce the dielectric constant, and how can I fix this?

Many traditional rigid water models (TIP3P, TIP4P variants) inaccurately describe dielectric properties due to parameterization limitations. The recently developed TIP4P-FB model addresses this specifically, accurately reproducing the dielectric constant across wide temperature and pressure ranges (77.3 ± 0.4 simulated vs. 78.4 experimental at ambient conditions) while maintaining accuracy for other thermodynamic properties [5]. This improvement was achieved through the ForceBalance automated parameterization using extensive experimental and ab initio reference data [5].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Unrealistic Protein-DNA Aggregation in Simulations

Problem: During protein-DNA simulations, you observe unrealistic aggregation or overly attractive interactions between biomolecules.

Diagnosis and Solutions:

- Identify the force field limitation: Traditional non-bonded parameters for nucleic acids, particularly the Cornell et al. set from 1995, overestimate base stacking and protein-DNA attractions [2].

- Apply non-bonded corrections: Implement the CUFIX (CHEMistry at HARvard Macromolecular Mechanics) correction, which recalibrates Lennard-Jones parameters to reproduce experimental osmotic pressure and resolves unrealistic aggregation [2].

- Validation protocol:

- Compare protein diffusion constants along DNA with experimental values

- Check for proper separation of DNA strands in duplex systems

- Verify interaction energies against quantum mechanical calculations where possible

Issue: Inaccurate 1-4 Interactions Affecting Torsional Profiles

Problem: Torsional energy barriers, geometries, or forces appear inaccurate, potentially due to improperly handled 1-4 interactions (atoms separated by three bonds).

Background: Traditional force fields use empirically scaled non-bonded interactions for 1-4 interactions, creating interdependence between dihedral terms and non-bonded interactions that complicates parametrization and reduces transferability [6].

Solution Approach:

- Adopt bonded coupling terms: Recent work demonstrates that 1-4 interactions can be accurately modeled using only bonded coupling terms, eliminating the need for arbitrarily scaled non-bonded interactions [6].

- Leverage automated parametrization: Use tools like the Q-Force toolkit to efficiently determine necessary coupling terms without manual adjustment [6].

- Validation metrics: This approach has shown sub-kcal/mol mean absolute error for various tested molecules and successfully reproduces ab initio gas and implicit solvent surfaces of alanine dipeptide [6].

Issue: Choosing Between Class I, II, and III Force Fields

Problem: Uncertainty in selecting the appropriate force field class for your specific application.

Decision Framework:

Table: Force Field Classes and Applications

| Class | Description | Examples | Best For |

|---|---|---|---|

| Class I | Harmonic bonds/angles, no cross-terms | AMBER, CHARMM, GROMOS, OPLS | Standard biomolecular simulations with balance of accuracy/speed |

| Class II | Anharmonic terms, cross-coupling between internal coordinates | MMFF94, UFF | Systems where accurate vibrational spectra or detailed mechanics are needed |

| Class III | Explicit polarization, special chemical effects | AMOEBA, DRUDE | Systems where electronic polarization effects are critical to phenomena |

Selection Protocol:

- Define accuracy requirements: Class I suffices for many structural studies; Class III necessary for dielectric properties or heterogeneous environments [1].

- Consider computational resources: Class III force fields are typically 5× or more computationally expensive than Class I [1] [5].

- Check parameter availability: Ensure all molecules in your system have supported parameters, as Class II/III force fields have more limited coverage.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Automated Force Field Parameterization Using ForceBalance

Purpose: Systematically derive accurate force field parameters using experimental and theoretical reference data [5].

Workflow:

Key Components:

- Reference Data: Combine experimental measurements (densities, enthalpies, dielectric constants) with high-level ab initio energy and force calculations [5].

- Simulation Engines: Interface with MD packages like GROMACS, TINKER, or OpenMM for property evaluation [5].

- Optimization Algorithm: Use gradient-based methods when good initial parameters exist, stochastic methods for rugged objective functions [5].

- Regularization: Apply Bayesian priors to prevent overfitting and maintain physical meaningfulness of parameters [5].

Validation: The method demonstrated high reproducibility in water model parameterization, with optimizations from different starting points converging to the same parameters [5].

Protocol 2: Development of Machine-Learned Force Fields with Spectroscopic Accuracy

Purpose: Construct force fields from high-level ab initio calculations using machine learning for spectroscopic accuracy in molecular dynamics [4].

Methodology:

Critical Steps:

- Symmetry Discovery: Implement multipartite matching algorithm to identify all relevant rigid and non-rigid molecular symmetries from MD trajectories [4].

- Reference Calculations: Compute energies and forces for molecular configurations using high-level quantum chemical methods (CCSD(T) where feasible) [4].

- sGDML Model Construction: Build symmetrized gradient-domain machine learning model that incorporates all identified physical symmetries in its kernel function [4].

- Converged MD Simulations: Execute molecular dynamics with fully quantized electrons and nuclei, achieving spectroscopic accuracy for molecules with up to a few dozen atoms [4].

Applications: This approach enables nanosecond-scale MD simulations at coupled cluster level of theory, which would otherwise require approximately a million CPU years for a single ethanol molecule using conventional methods [4].

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table: Essential Resources for Force Field Development and Application

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| ForceBalance [5] | Parameterization Tool | Automatically optimizes force field parameters against experimental/theoretical data | Systematic development of accurate parameters (e.g., TIP3P-FB, TIP4P-FB water models) |

| Q-Force Toolkit [6] | Parametrization Automation | Determines bonded coupling terms for 1-4 interactions | Eliminating empirical non-bonded scaling in traditional force fields |

| sGDML [4] | Machine Learning Framework | Constructs force fields from high-level ab initio calculations | Creating spectroscopically accurate force fields for small molecules |

| AMBER Force Fields [2] [7] | Biomolecular Force Field | Provides parameters for proteins, nucleic acids, small molecules | Most widely used force field family for biomolecular simulations |

| CHARMM Force Fields [7] | Biomolecular Force Field | All-atom parameters for diverse biomolecules | Alternative to AMBER with different combining rules and parametrization philosophy |

| GROMACS [1] [7] | MD Simulation Engine | Efficient molecular dynamics simulation package | Production MD simulations with various force fields; requires proper comb-rule settings |

| CUFIX Correction [2] | Non-bonded Parameter Set | Corrected Lennard-Jones parameters for nucleic acids | Resolving unrealistic DNA condensation and protein-DNA interactions |

In Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, the potential energy function is a fundamental empirical model that calculates the total potential energy of a system as a function of the nuclear coordinates. This function approximates the quantum mechanical energy surface with a classical mechanical model, enabling simulations of large biomolecular systems like proteins in the presence of water, which are essential for Computational Structure-Based Drug Discovery [8]. The class I additive potential energy function, which is the most common type in biomolecular simulations, is a sum of bonded and nonbonded energy terms [8].

Core Components: Bonded vs. Nonbonded Interactions

The total potential energy ((E{total})) is given by the sum of bonded ((E{bonded})) and nonbonded ((E_{nonbonded})) energy terms. The following workflow outlines the process of defining and utilizing this function in a typical molecular dynamics study.

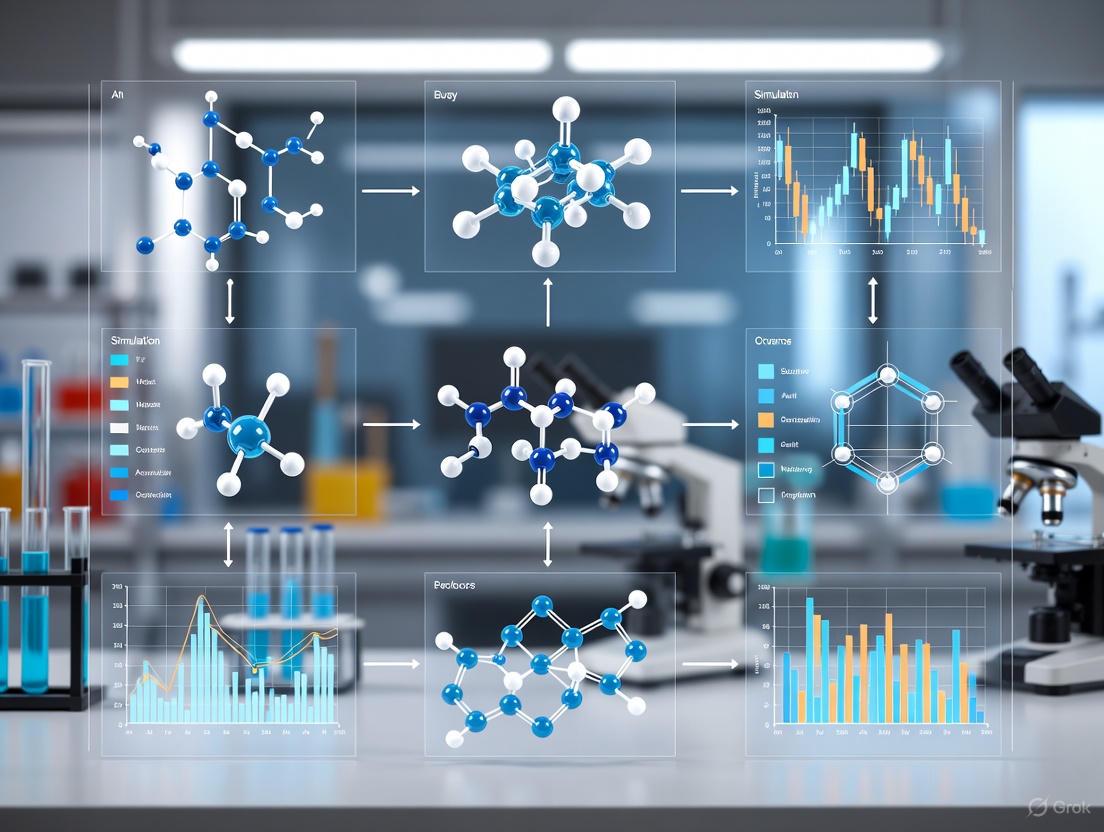

Diagram 1: Potential energy function decomposition and simulation workflow.

Bonded Interactions

Bonded interactions describe the energy associated with the covalent bond structure of a molecule and comprise four primary types [8]:

- Bond Stretching: This term models the energy required to stretch or compress a covalent bond from its equilibrium length. It is represented as a harmonic oscillator: (E{bond} = \sum{bonds} Kb(b - b0)^2), where (Kb) is the bond force constant, (b) is the actual bond length, and (b0) is the reference bond length.

- Angle Bending: This term models the energy associated with bending the angle between two adjacent covalent bonds. It is also represented as a harmonic oscillator: (E{angle} = \sum{angles} K\theta(\theta - \theta0)^2), where (K\theta) is the angle force constant, (\theta) is the actual angle, and (\theta0) is the reference angle.

- Dihedral Torsions: This term describes the energy associated with rotation around a central bond, defined by four sequentially bonded atoms. It is represented by a periodic function: (E{dihedral} = \sum{dihedrals} \sum{n=1}^{6} K{\phi,n}(1 + \cos(n\phi - \deltan))), where (K{\phi,n}) is the dihedral force constant, (n) is the multiplicity, (\phi) is the torsional angle, and (\delta_n) is the phase angle. This term is crucial for correctly reproducing conformational energetics [8].

- Improper Dihedrals: This term is primarily used to enforce planarity in certain molecular structures (e.g., aromatic rings) or to maintain chirality at a central atom. It is often modeled as a harmonic function: (E{improper} = \sum{impropers} K\varphi(\varphi - \varphi0)^2) [8].

Nonbonded Interactions

Nonbonded interactions describe the energy between atoms that are not directly connected by covalent bonds. They are crucial for modeling intermolecular forces and intramolecular long-range effects [8]. The two key components are:

- Electrostatics: This term describes the attractive or repulsive forces between partial atomic charges. It is calculated using Coulomb's law: (E{electrostatic} = \sum{nonbonded\ pairs\ i,j} \frac{qi qj}{4\pi D r{ij}}), where (qi) and (qj) are the partial charges, (D) is the dielectric constant, and (r{ij}) is the distance between atoms.

- van der Waals Interactions: This term accounts for the short-range attractive (dispersion) and repulsive (Pauli exclusion) forces. It is most commonly modeled by the Lennard-Jones 12-6 potential: (E{vdW} = \sum{nonbonded\ pairs\ i,j} \varepsilon{ij} \left[ \left( \frac{R{min, ij}}{r{ij}} \right)^{12} - 2 \left( \frac{R{min, ij}}{r{ij}} \right)^6 \right]), where (\varepsilon{ij}) is the well depth and (R_{min, ij}) is the distance at which the potential is minimum [8].

Table 1: Summary of Potential Energy Function Terms and Parameters [8]

| Term Type | Specific Term | Mathematical Formulation | Key Parameters | Physical Description |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bonded | Bond Stretching | (E = Kb(b - b0)^2) | (Kb) (force constant), (b0) (ref. length) | Energy of vibrating covalent bond |

| Angle Bending | (E = K\theta(\theta - \theta0)^2) | (K\theta) (force constant), (\theta0) (ref. angle) | Energy of bending between three atoms | |

| Dihedral Torsion | (E = \sum{n} K{\phi,n}[1 + \cos(n\phi - \delta_n)]) | (K{\phi,n}) (amplitude), (n) (multiplicity), (\deltan) (phase) | Energy of rotation around a central bond | |

| Improper Dihedral | (E = K\varphi(\varphi - \varphi0)^2) | (K\varphi) (force constant), (\varphi0) (ref. angle) | Energy to maintain planarity or chirality | |

| Nonbonded | Electrostatics | (E = \frac{qi qj}{4\pi D r_{ij}}) | (qi, qj) (partial charges) | Interaction between atomic partial charges |

| van der Waals | (E = \varepsilon{ij}\left[\left(\frac{R{min,ij}}{r{ij}}\right)^{12} - 2\left(\frac{R{min,ij}}{r_{ij}}\right)^6\right]) | (\varepsilon{ij}) (well depth), (R{min,ij}) (vdW radius) | Attractive and repulsive dispersion forces |

Troubleshooting Guide: Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: My simulation is unstable and "explodes." What should I do?

Problem: The simulation fails due to a sudden, unphysical increase in energy, often causing atoms to fly apart.

Diagnosis and Solution Protocol: Follow this logical troubleshooting pathway to identify and resolve the root cause.

Diagram 2: Troubleshooting unstable simulations.

Detailed Steps:

- Reduce the Time Step: The integration time step may be too large to accurately capture the fastest vibrations (e.g., bonds with hydrogen atoms). Solution: Decrease the MD time step [9].

- Check System Temperature: Excessively high temperature can impart too much kinetic energy, breaking bonds and causing instability. Solution: Decrease the simulation temperature [9].

- Validate Force Field and Topology: Incorrect parameters or missing terms (like improper dihedrals needed to maintain planarity) can lead to unphysical geometries. For simulations of non-natural molecules like β-peptides, ensure the force field has been properly extended and validated for those components [10]. Also, verify that molecular termini (e.g., neutral amine, N-methylamide) are correctly defined and supported by your chosen force field [10].

- Adjust System Packing (Reactive Simulations): In specialized simulations like NanoReactors, high density can force molecules too close together, leading to violent reactions and energy spikes. Solution: Increase the

MinVolumeFractionparameter or decrease the initial system density [9].

FAQ 2: My simulation is not producing the expected results (e.g., wrong conformation).

Problem: The simulated system does not adopt the known experimental structure or exhibit expected properties.

Diagnosis and Solution Protocol:

Verify Force Field Selection: Different force fields have specific strengths, weaknesses, and domains of applicability. A force field that performs well for proteins may not be accurate for other molecules like β-peptides without specific parameterization [10].

- Experimental Protocol for Validation:

- Reference Systems: Simulate a system with a known experimental outcome (e.g., a β-peptide that folds into a specific helix) as a benchmark [10].

- Comparative Testing: Run benchmark simulations using multiple force fields (e.g., CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS) and compare the results to experimental data. Studies have shown that performance can vary significantly, with some force fields accurately reproducing structures while others fail without further parametrization [10].

- Check Key Interactions: Analyze if specific interactions, like backbone dihedrals in peptidomimetics, are correctly parametrized. Inaccurate torsional energy profiles are a common source of error [10].

- Experimental Protocol for Validation:

Check Dihedral Term Parametrization: The torsional terms are critical for determining the relative energies of different conformers. Solution: If available, use a force field version where dihedral parameters have been refined against high-level quantum-chemical calculations, as this has been shown to significantly improve the accuracy of reproduced structures [10].

FAQ 3: My MD simulations are running too slowly. How can I improve performance?

Problem: The simulation takes an impractically long time to complete, hindering research progress.

Diagnosis and Solution Protocol:

- Reduce System Size: The computational cost scales with the number of particles. Solution: Minimize the number of solvent molecules or use a smaller, representative fragment of your system where possible [9].

- Optimize Simulation Length: Solution: Decrease the number of simulation cycles if the phenomenon of interest occurs on a shorter timescale [9].

- Increase Time Step (with care): Solution: Increase the MD time step. This can be done more safely by using algorithms that constrain the fastest vibrations (e.g., bonds involving hydrogen), allowing for a larger time step without sacrificing stability [9].

- Use Efficient Force Fields for Scouting: Solution: For initial setup and scouting (e.g., checking density fluctuations), run the simulation with a fast, non-reactive force field like UFF. This can help you refine settings quickly before running a more expensive production simulation with a high-accuracy force field [9].

Table 2: Summary of Common MD Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Primary Cause | Recommended Solution | Key Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Simulation "explodes" | Time step too large | Decrease MD time step | [9] |

| Temperature too high | Decrease temperature | [9] | |

| Incorrect system density/packing | Increase MinVolumeFraction or decrease density |

[9] | |

| Wrong conformation | Inappropriate force field | Benchmark and select/parametrize a suitable force field | [10] |

| Poor dihedral parametrization | Use QM-refined torsional parameters | [10] | |

| Simulation too slow | Too many atoms | Reduce system size | [9] |

| Too long simulation | Decrease number of cycles | [9] | |

| Small time step | Increase time step (use constraints) | [9] | |

| No reactions observed | Unreactive potential | Use reactive potential (ReaxFF, DFTB) | [9] |

| Low system density/energy | Increase temperature, decrease MinVolumeFraction |

[9] |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This section details the essential computational "reagents" — force fields and simulation packages — required for setting up and running accurate molecular dynamics simulations.

Table 3: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Dynamics

| Reagent / Tool | Category | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CHARMM36/36m [7] [10] | All-Atom Force Field | Provides parameters for proteins, nucleic acids, lipids, and carbohydrates. | Often includes improved treatment of backbone dihedrals. Ported for use in GROMACS. Known for high performance in reproducing experimental structures of diverse systems, including β-peptides [10]. |

| AMBER (e.g., ff99SB-ILDN, ff03) [7] [10] | All-Atom Force Field | Empirically parametrized for biomolecules. Compatible with GAFF for small molecules. | Good performance for systems containing cyclic β-amino acids; may require extension for other peptidomimetics [10]. |

| GROMOS (e.g., 54A7, 54A8) [7] [10] | United-Atom Force Field | Integrates with GROMOS simulation suite; parameters for biomolecules and solvents. | Supports β-peptides "out-of-the-box," but performance may be lower compared to other parametrized force fields. Users should be aware of historical parametrization issues with cut-off schemes [7] [10]. |

| OPLS-AA/M [7] | All-Atom Force Field | Optimized for simulating liquid systems and biomolecules. | Known for accurate reproduction of condensed-phase properties. |

| GROMACS [10] | MD Simulation Engine | High-performance, parallelized software for running MD simulations. | Can be used as a common engine for simulations with multiple force fields (CHARMM, AMBER, GROMOS), allowing for impartial comparisons [10]. |

| Antechamber/GAFF [7] | Parameterization Tool | Generates parameters for small organic molecules compatible with AMBER force fields. | Essential for drug discovery when simulating novel ligands. |

| PyMOL / pmlbeta [10] | Modeling & Visualization | Molecular graphics system for model building, visualization, and analysis. | The pmlbeta extension is used specifically for building models of β-peptides [10]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the primary strategies for deriving force field parameters, and when should I use each?

Researchers can primarily choose between several parameterization strategies, each with distinct advantages and ideal use cases, as summarized in the table below.

Table 1: Comparison of Force Field Parameterization Strategies

| Strategy | Core Methodology | Best For | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|---|

| Data-Driven & ML-Powered | Uses Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) trained on vast QM datasets to predict parameters. [11] | Covering expansive chemical space (e.g., drug-like molecules); high-throughput parameterization. [11] | State-of-the-art accuracy and coverage; requires significant initial data and training. [11] |

| Iterative QM Optimization | Automatically cycles between parameter optimization, MD sampling, and new QM calculations. [12] | Systems with rugged potential energy surfaces (e.g., peptides); achieving high accuracy for specific molecules. [12] | Uses a validation set to prevent overfitting; can be computationally expensive. [12] |

| Modular & QM-Based | Divides large molecules into fragments; parameters are derived via QM calculations and then reassembled. [13] | Complex molecules with repeating motifs (e.g., mycobacterial lipids); ensuring consistency. [13] | Maintains transferability and captures local chemical environments effectively. [13] |

| Genetic Algorithms (GA) | Employs evolutionary algorithms to optimize parameters against QM or experimental target data. [14] [15] | Multidimensional parameter optimization where parameters are tightly coupled (e.g., van der Waals). [15] | Efficiently navigates complex parameter spaces; avoids getting trapped in local minima. [15] |

| Toolkit-Guided Workflow | Follows a step-by-step GUI-based workflow (e.g., Force Field Toolkit, ffTK) for manual parameterization. [16] | Researchers new to parameterization; developing CHARMM-compatible parameters with a guided process. [16] | Minimizes barriers and error-prone tasks; provides a clear, organized workflow. [16] |

FAQ 2: How can I ensure my parameterized force field is accurate and not overfit?

Preventing overfitting requires robust validation techniques. A key method is the use of a separate validation set of conformations not used during the optimization process to monitor for convergence and flag when overfitting occurs. [12] Furthermore, parameters must be validated by running MD simulations and comparing the results to experimental observables, such as density, heat of vaporization, or diffusion coefficients, which were not part of the fitting process. [14] [15] For example, a force field for mycobacterial lipids was validated by showing its MD simulations reproduced experimental rigidity and diffusion rates. [13]

FAQ 3: My molecule is not fully covered by general force fields. What is the best way to handle missing parameters?

For missing torsion parameters, the recommended approach is to perform a quantum chemical rotational scan and fit the resulting energy profile to the dihedral potential function of your chosen force field. [16] [15] For missing van der Waals or other parameters, a modern strategy is to employ a fragmentation approach: cleave your molecule into smaller, manageable fragments that capture the local chemical environment, parameterize these fragments using QM calculations, and then reassemble the complete molecule. [11] [13] This ensures parameters are dominated by local structures and are transferable. [11]

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue 1: Poor Reproduction of Quantum Mechanical Torsional Energy Profiles

- Problem: The molecular mechanics (MM) energies from a torsion scan deviate significantly from the reference quantum mechanics (QM) data.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Inadequate QM Reference Data.

- Solution: Ensure the QM calculation uses an appropriate level of theory (e.g., B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP is often a good balance of accuracy and cost for organic molecules). [11] Generate sufficient data points along the dihedral angle to fully capture the energy profile.

- Cause 2: Over-simplified Dihedral Parameterization.

- Solution: Avoid fitting only a single dihedral term. The potential is a Fourier series (

Vn,n,γ). Use optimization algorithms like Genetic Algorithms to fit multiple Fourier terms simultaneously to better match the QM profile. [15]

- Solution: Avoid fitting only a single dihedral term. The potential is a Fourier series (

- Cause 3: Coupling with Other Degrees of Freedom.

- Solution: When scanning the target dihedral, ensure that other internal coordinates (like adjacent bonds and angles) are relaxed or accounted for in the QM calculation to isolate the torsional energy. [16]

- Cause 1: Inadequate QM Reference Data.

Issue 2: Force Field Fails to Reproduce Experimental Condensed-Phase Properties

- Problem: MD simulations using the new parameters produce inaccurate physical properties like density, heat of vaporization, or free energy of solvation.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: Poorly Optimized Van der Waals (vdW) Parameters.

- Solution: vdW parameters (σ and ε) are tightly coupled and significantly impact condensed-phase properties. Instead of hand-tuning, use a systematic optimization algorithm like a Genetic Algorithm. The objective function should target experimental properties like density and heat of vaporization. [15]

- Cause 2: Electrostatic Interactions Dominating Errors.

- Solution: Re-evaluate the partial charge derivation method. For CHARMM-like force fields, optimize charges to reproduce water-interaction profiles. [16] For AMBER-like force fields, the RESP method fitting to the electrostatic potential is standard. [13] [15] Ensure charge conservation for the entire molecule. [11]

- Cause 3: Lack of Validation Against a Broad Set of Data.

- Solution: A force field that performs well on one property may fail on another. Validate against multiple experimental properties. For instance, a well-parameterized model should reproduce both static (density) and dynamic (diffusion coefficient) properties. [15]

- Cause 1: Poorly Optimized Van der Waals (vdW) Parameters.

Issue 3: Parameterization is Too Slow or Not Scalable to Large Molecules

- Problem: The computational cost of generating QM target data or optimizing parameters is prohibitive for large or complex molecules.

- Potential Causes & Solutions:

- Cause 1: QM Calculations on the Entire Molecule.

- Solution: Adopt a divide-and-conquer strategy. For large lipids or cofactors, the molecule can be divided into chemically logical segments or modules. QM calculations are run on these smaller modules, and the parameters are then combined for the full molecule, dramatically reducing cost. [13]

- Cause 2: Manual, Multi-step Parameterization.

- Solution: Leverage automated and iterative workflows. Tools have been developed that automate the cycle of parameter optimization, running dynamics to sample new conformations, computing new QM data, and iterating. [12] For broad chemical space coverage, use pre-trained machine learning models like ByteFF or Espaloma that can predict parameters end-to-end without manual intervention for each new molecule. [11]

- Cause 1: QM Calculations on the Entire Molecule.

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol: A Modular QM Parameterization for Complex Molecules

This protocol is adapted from methodologies used to parameterize lipids for mycobacterial membranes. [13]

System Preparation and Fragmentation:

- Start with a 3D structure of the target molecule.

- Divide the large molecule into smaller, manageable segments at chemically sensible junctions (e.g., cleaving long aliphatic tails from a core headgroup).

- Cap the cleaved bonds with appropriate chemical groups (e.g., methyl groups) to maintain valency.

Quantum Mechanical Target Data Generation:

- For each segment, generate multiple conformations (e.g., 25 conformations randomly selected from a preliminary MD simulation). [13]

- Perform geometry optimization for each conformation at a defined QM level (e.g., B3LYP/def2SVP).

- For the optimized geometry, derive partial atomic charges using the Restrained Electrostatic Potential (RESP) method at a higher level of theory (e.g., B3LYP/def2TZVP). [13]

Torsion Parameter Optimization:

- Identify all rotatable dihedral angles involving heavy atoms within the segments.

- Perform a QM rotational scan for each target dihedral, recording the energy profile.

- Optimize the dihedral force constants (

Vn) and periodicities (n) to minimize the difference between the MM and QM energy profiles. Genetic Algorithms are highly effective for this. [15]

Parameter Assembly and Validation:

- Integrate the partial charges from all segments to obtain the total charge for the full molecule, ensuring net charge conservation.

- Combine the bonded and torsion parameters. For bond and angle parameters not optimized in this workflow, transfer them from a established general force field (e.g., GAFF). [13]

- Validate the final parameter set by running an MD simulation and comparing the results to available experimental data (e.g., bilayer properties or diffusion rates). [13]

Protocol: Data-Driven Force Field Generation with Machine Learning

This protocol outlines the workflow behind modern, data-driven force fields like ByteFF. [11]

Dataset Curation:

Large-Scale QM Target Calculation:

- For each molecular fragment, generate a 3D conformation (e.g., using RDKit).

- Perform high-throughput QM calculations at a consistent level of theory (e.g., B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP) to generate two primary datasets:

Machine Learning Model Training:

- Design a symmetry-preserving Graph Neural Network (GNN) architecture. The model takes molecular graphs as input.

- Train the GNN to predict all bonded (bonds, angles, torsions) and non-bonded (vdW, charges) parameters simultaneously. [11]

- Employ a carefully designed training strategy that may include a differentiable partial Hessian loss to ensure accurate geometry prediction. [11]

Benchmarking and Deployment:

- Rigorously benchmark the trained model on held-out test sets of molecules.

- Evaluate performance on predicting relaxed geometries, torsional energy profiles, and conformational energies and forces. [11]

- Deploy the model as a tool for rapid parameterization of new, drug-like molecules.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Software Tools and Methods for Force Field Parameterization

| Tool / Method Name | Type | Primary Function | Compatibility / Key Feature |

|---|---|---|---|

| ByteFF [11] | Data-Driven Force Field | End-to-end prediction of MM parameters for drug-like molecules using a GNN. | Amber-compatible; trained on a massive QM dataset of 2.4M fragments and 3.2M torsions. [11] |

| Force Field Toolkit (ffTK) [16] | Software Plugin (VMD) | GUI-based workflow to guide users through CHARMM-compatible parameterization. | Modular workflow for charges, bonds/angles, and dihedrals; automates tedious tasks. [16] |

| Genetic Algorithm (GA) [14] [15] | Optimization Algorithm | Efficiently searches multidimensional parameter space to fit QM or experimental data. | Ideal for coupled parameters like van der Waals terms; avoids local minima. [15] |

| BLipidFF Protocol [13] | Parameterization Methodology | A modular, QM-based approach for parameterizing complex lipids and large molecules. | Provides a standardized framework; uses RESP charges and torsion fitting. [13] |

| Iterative Optimization [12] | Parameterization Algorithm | Automates parameter fitting, dynamics sampling, and iterative QM data expansion. | Uses a validation set to determine convergence and prevent overfitting. [12] |

| B3LYP-D3(BJ)/DZVP [11] | Quantum Chemistry Method | A specific level of theory for QM calculations balancing accuracy and computational cost. | Commonly used for generating target data for organic/drug-like molecules. [11] |

| Restrained Electrostatic Potential (RESP) [13] [15] | Charge Fitting Method | Derives partial atomic charges by fitting to the quantum mechanical electrostatic potential. | Standard method for AMBER-like force fields; helps prevent over-polarization. [13] |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Inadequate Sampling in Biomolecular Simulations

Reported Issue: The simulation fails to explore all functionally relevant conformational states, with the system becoming trapped in a non-representative region of the energy landscape.

Underlying Cause: Biomolecular systems are governed by rough energy landscapes featuring numerous local minima separated by high-energy barriers [17]. Conventional Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations often cannot overcome these barriers within practical computational timescales, leading to non-ergodic sampling where the system gets stuck in a single metastable state [17] [18].

Diagnosis Steps:

- Monitor Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD): Check if the RMSD plateaus and shows no further fluctuations, indicating confinement to a single energy basin.

- Analyze Energy Time Series: Plot the potential energy over time. A lack of significant fluctuations can suggest insufficient sampling of different states.

- Use Community Analysis Tools: Employ techniques like Common Neighborhood Analysis [19] to identify and classify local atomic structures throughout the trajectory, confirming a lack of diversity.

Resolution: Implement enhanced sampling algorithms designed to facilitate barrier crossing.

- For a rough landscape that is not excessively complex, use Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD). This method runs parallel simulations at different temperatures and allows exchanges between them, enabling a random walk in temperature space and helping to escape local minima [17] [18].

- For systems where specific reaction coordinates are known, use Metadynamics. This method discourages revisiting previously sampled states by adding a history-dependent bias potential, effectively "filling" free energy wells to push the system to explore new areas [17].

Guide 2: Managing Prohibitive Computational Cost in Large-Scale Simulations

Reported Issue: Simulating large systems (e.g., >25,000 atoms) over biologically relevant timescales (microseconds+) is computationally infeasible, requiring months of computation and expensive supercomputing resources [17].

Underlying Cause: The high computational cost of all-atom MD simulations limits accessible timescales and system sizes. This is exacerbated by the small integration time steps (e.g., 2 femtoseconds) required for numerical stability in traditional force-evaluation methods [20].

Diagnosis Steps:

- Benchmark System Size: Determine the number of atoms, simulation box size, and desired simulation time.

- Profile Computational Resources: Assess the available computational resources (CPU cores, GPU acceleration) and estimate the projected simulation wall time using standard MD software performance metrics.

Resolution:

- For exploring equilibrium properties, leverage Generalized Simulated Annealing (GSA). This method is well-suited for large, flexible macromolecular complexes and can characterize conformational ensembles at a relatively low computational cost [17] [18].

- For accelerating long-timescale dynamics, consider novel machine learning approaches. Emerging frameworks use autoregressive neural networks to directly update atomic positions, bypassing traditional force calculations and allowing for time steps at least one order of magnitude larger than conventional MD [20].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the most common enhanced sampling methods, and how do I choose?

A: The choice depends on your system's characteristics and the property you wish to study [17].

- Replica-Exchange MD (REMD): Best for a broad range of systems, from small peptides to large molecular complexes. It is most effective when the energy landscape is not excessively rough [17] [18].

- Metadynamics: Ideal when you have prior knowledge of a few key collective variables (e.g., a distance, angle, or dihedral) that describe the process of interest. It provides a good exploration of the free energy landscape [17].

- Simulated Annealing (and GSA): Well-suited for characterizing very flexible systems and for structure prediction of large macromolecular complexes [17].

Q2: My simulation results are not reproducible. Could this be a sampling issue?

A: Yes, inadequate sampling is a primary cause of non-reproducible results. If independent simulations become trapped in different local minima on the rough energy landscape, they will yield different structural, dynamic, and thermodynamic averages [17]. Employing enhanced sampling techniques ensures a more comprehensive and consistent exploration of the conformational space.

Q3: How does the selection of a potential function impact sampling accuracy?

A: The potential function is the physical foundation of MD simulation, and its accuracy directly determines the reliability of the results [19]. An poor choice can create an inaccurate energy landscape. For example, a potential function fitted only to solid-state properties may fail to correctly predict solid-liquid interface phenomena [19]. Always select a potential (e.g., EAM for metals, Tersoff for covalent materials) that is validated for the specific phases and properties you are investigating.

Enhanced Sampling Methods: Comparative Analysis

The table below summarizes the core enhanced sampling techniques, their mechanisms, and typical applications to aid in method selection.

| Method Name | Core Mechanism | Key Advantage | Ideal Use Case | Software Implementation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) [17] [18] | Parallel simulations at different temperatures exchange states based on Monte Carlo criteria. | Efficient random walk in temperature space helps escape local minima. | Folding/unfolding of peptides and small proteins; studying free energy landscapes. | GROMACS [17], AMBER [17], NAMD [17] |

| Metadynamics [17] [18] | A history-dependent bias potential is added to collective variables to discourage revisiting states. | Effectively explores and maps free energy surfaces; good for pre-defined reaction coordinates. | Protein-ligand binding, conformational changes, chemical reactions. | PLUMED (with GROMACS, NAMD, etc.) [17] |

| Simulated Annealing [17] | The simulation temperature is gradually decreased from a high value according to a defined schedule. | Good for finding global energy minima and characterizing flexible structures. | NMR structure refinement, predicting native states of very flexible biomolecules. | AMS [21], various other MD packages |

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Protocol 1: Setting Up a Replica-Exchange MD (REMD) Simulation

This protocol outlines the steps for configuring a REMD simulation to study protein folding [17].

- System Preparation: Construct the initial protein structure in a solvated box with ions, as with any standard MD simulation.

- Replica Parameters: Determine the number of replicas (typically 24-64) and the range of temperatures. The highest temperature should be high enough to denature the protein but not so high that it reduces efficiency [17].

- Equilibration: Briefly equilibrate each replica at its assigned temperature.

- Production Run: Run parallel MD simulations for each replica. Periodically attempt to swap configurations between adjacent temperatures. The acceptance probability is based on the Metropolis criterion, considering the potential energies and temperatures of the two replicas [17].

- Analysis: Use the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) to reconstruct the thermodynamic properties at the temperature of interest from the ensemble of all replicas.

Protocol 2: Applying Metadynamics to Study a Conformational Change

This protocol describes using metadynamics to drive and study a large-scale conformational change in an ion channel [17] [18].

- Identify Collective Variables (CVs): Select 1-3 physically meaningful CVs that describe the transition (e.g., radius of gyration, a specific dihedral angle, or distance between key residues).

- Define Bias Parameters: Set the height and width of the Gaussian hills that will be deposited. These determine the resolution and speed of free energy exploration.

- Run Biased Simulation: Perform the MD simulation, periodically adding a Gaussian bias potential to the current values of the CVs. This discourages the system from returning to the same spot in CV space.

- Reconstruct Free Energy: The negative of the sum of the deposited bias potentials provides an estimate of the underlying free energy surface as a function of the chosen CVs.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item / Software | Function / Purpose |

|---|---|

| LAMMPS | A highly flexible MD simulator with robust parallel computing capabilities, ideal for large-scale metallic, alloy, and material systems [19]. |

| GROMACS | MD software optimized for high performance on biomolecular systems (proteins, lipids, nucleic acids) and soft matter [19] [17]. |

| PLUMED | A plugin that enables enhanced sampling techniques, including metadynamics, in various MD codes like GROMACS and NAMD [17]. |

| EAM Potential | An embedded-atom method potential function used for metals and alloys; it accounts for multi-body interactions, providing a more accurate description of metallic bonding [19]. |

| Tersoff Potential | An empirical interatomic potential for covalent materials (e.g., silicon, carbon); it dynamically reflects the chemical environment to accurately model bond formation and breaking [19]. |

Method Selection and Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the decision pathway for selecting an appropriate enhanced sampling method based on system characteristics and research goals.

Advanced Sampling and Machine Learning to Overcome Barriers

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations are powerful tools for studying biomolecular systems, but they are often limited by inadequate sampling of conformational states due to rough energy landscapes with many local minima separated by high-energy barriers. Enhanced sampling methods address this problem by facilitating the escape from these local minima, allowing for more thorough exploration of the free energy surface. Among these methods, Replica-Exchange Molecular Dynamics (REMD) and Metadynamics have gained significant popularity for studying complex biological processes such as protein folding, aggregation, and ligand binding. These techniques are particularly valuable for investigating processes that occur on timescales inaccessible to conventional MD simulations, such as protein aggregation diseases including Alzheimer's and Parkinson's disease [22] [17].

Troubleshooting Guides

REMD Troubleshooting Guide

Table 1: Common REMD Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Diagnostic Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Poor replica exchange rates | Temperature spacing too wide | Reduce temperature difference between adjacent replicas; aim for exchange rates of 15-25% [22] [17]. |

| Inadequate simulation time | Extend simulation time to improve sampling statistics. | |

| System trapped in local minima | Insufficient replicas | Increase number of replicas to better cover temperature range. |

| Incorrect temperature range | Ensure maximum temperature is slightly above where folding enthalpy vanishes [17]. | |

| Simulation instability | Force field inaccuracies | Verify force field compatibility with your system. |

| Incorrect parameters | Check water model, boundary conditions, and thermostat settings [22]. | |

| Low efficiency for large systems | High computational cost | Consider multiplexed REMD (M-REMD) or Hamiltonian REMD (H-REMD) [23] [17]. |

Metadynamics Troubleshooting Guide

Table 2: Common Metadynamics Issues and Solutions

| Problem | Possible Causes | Solutions & Diagnostic Steps |

|---|---|---|

| Free Energy Surface (FES) inaccuracies | Poor Collective Variable (CV) choice | Select CVs that accurately describe reaction pathway; use essential coordinates or Sketch-Map [24]. |

| Incorrect Gaussian parameters | Adjust Gaussian height and width; use well-tempered metadynamics for adaptive Gaussians [24]. | |

| Minimum points don't match expected structures | FES reconstruction artifacts | Gaussian contributions may cover unvisited CV space; verify with trajectory data [25]. |

| Slow convergence | Suboptimal deposition rate | Adjust frequency of Gaussian deposition and initial height [24]. |

| High-dimensional CV space failure | Too many CVs | Limit to 3-4 CVs maximum; use bias-exchange MTD or high-dimensional approaches like NN2B for more CVs [24]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

REMD FAQs

Q: What is the optimal number of replicas and temperature distribution for my REMD simulation? A: The optimal number depends on your system size and temperature range. For protein systems, temperature spacing should be set to achieve exchange rates of 15-25%. The maximum temperature should be chosen slightly above the temperature at which the enthalpy for folding vanishes. For larger systems, consider using Hamiltonian REMD or multiplexed REMD to improve efficiency [17].

Q: How do I analyze the free energy landscape from REMD simulations? A: Free energy landscapes can be constructed from REMD trajectories using the weighted histogram analysis method (WHAM) or similar techniques. The free energy is calculated as a function of selected reaction coordinates, providing insights into stable states and transition pathways [22].

Q: Can REMD be applied to constant pressure simulations? A: Yes, REMD can be adapted to the NPT ensemble with the Hamiltonian modified to include the PV term. The contribution of volume fluctuations to the total energy is typically negligible [22].

Metadynamics FAQs

Q: How do I select appropriate collective variables for metadynamics? A: Collective variables should describe all relevant slow degrees of freedom of the process being studied. Good CVs are often system-specific but may include distances, angles, dihedrals, or coordination numbers. For complex systems, automated procedures like essential coordinates, Sketch-Map, or non-linear data-driven collective variables can help [24].

Q: Why can't I find my FES minimum points in the actual simulation trajectory? A: This is normal behavior in metadynamics. The FES is reconstructed from Gaussian contributions that extend beyond visited points in the trajectory. Each minimum corresponds to CV values, not one specific coordinate set. Any structure with those CV values belongs to that minimum [25].

Q: What is the difference between standard and well-tempered metadynamics? A: Well-tempered metadynamics uses a bias factor that gradually reduces the height of added Gaussians as simulation progresses, providing more accurate free energy estimates and better convergence compared to standard metadynamics [24].

Q: How do I extract structural configurations corresponding to FES minima? A: While there isn't a single structure for each minimum, you can identify trajectory frames with CV values closest to the minimum point. For the global minimum, look for the most frequently visited basin in the trajectory [25].

Experimental Protocols

REMD Protocol for Peptide Aggregation Studies

This protocol follows the methodology for studying the dimerization of the 11-25 fragment of human islet amyloid polypeptide (hIAPP(11-25)) as described in PMC literature [22].

System Setup:

- Construct initial peptide configuration using molecular modeling software (e.g., VMD)

- Solvate the system in an appropriate water model (e.g., TIP3P)

- Add counterions to neutralize system charge

- Employ energy minimization using steepest descent algorithm

- Equilibrate system with position restraints on peptide atoms

REMD Simulation Parameters:

- Number of replicas: Typically 24-72 depending on system size and temperature range

- Temperature distribution: Exponential spacing between 300K and 500K

- Exchange attempt frequency: Every 1-2 ps

- Integration time step: 1-2 fs

- Thermostat: Nose-Hoover or Langevin thermostat

- Barostat: Parrinello-Rahman for NPT simulations

- Production run: 50-100 ns per replica

Analysis Methods:

- Calculate free energy landscapes using WHAM

- Analyze secondary structure evolution

- Identify stable oligomeric states

- Compute contact maps and radial distribution functions

Metadynamics Protocol for Protein Folding Studies

System Preparation:

- Start from unfolded or extended protein structure

- Solvate in appropriate water box with sufficient padding

- Add ions to physiological concentration (150 mM NaCl)

- Minimize energy and equilibrate with restraints

Metadynamics Parameters:

- Collective variables: Typically 1-3 CVs (e.g., RMSD, radius of gyration, native contacts)

- Gaussian height: 0.5-2.0 kJ/mol

- Gaussian width: Adjusted to CV fluctuations in short unbiased simulation

- Deposition rate: Every 500-1000 steps

- Bias factor: 10-60 for well-tempered metadynamics

- Simulation length: 100-500 ns depending on system size

Convergence Assessment:

- Monitor free energy estimate as function of simulation time

- Check for random walk behavior in CV space

- Verify stability of free energy differences between minima

Workflow Visualization

REMD Workflow

Metadynamics Workflow

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Enhanced Sampling Simulations

| Item | Function/Application | Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD simulation package for REMD and metadynamics | Version 4.5.3 or higher; includes REMD and PLUMED interface [22] |

| PLUMED | Plugin for enhanced sampling techniques | Enables metadynamics, umbrella sampling, etc. [24] |

| AMBER | MD software with REMD implementation | Alternative to GROMACS; includes REMD modules [17] |

| NAMD | Scalable MD for large systems | Supports metadynamics and replica exchange [17] |

| VMD | Molecular visualization and analysis | Structure building, trajectory analysis, and visualization [22] |

| HPC Cluster | High-performance computing resources | Intel Xeon processors, MPI library, 2 cores per replica minimum [22] |

Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFFs) represent a transformative advancement in molecular simulations, bridging the gap between quantum mechanical accuracy and molecular mechanics efficiency. By leveraging differentiable neural functions parameterized to fit ab initio energies and forces through automatic differentiation, MLFFs achieve unprecedented accuracy while maintaining computational feasibility for meaningful molecular dynamics simulations. Current implementations have largely surpassed the chemical accuracy threshold of 1 kcal/mol for limited chemical spaces, though significant challenges remain in computational speed, stability, and generalizability to diverse molecular systems. This technical support center addresses the practical implementation hurdles researchers face when deploying MLFFs in pharmaceutical and materials science applications, providing troubleshooting guidance and methodological frameworks to enhance simulation accuracy and reliability.

Foundational Concepts: MLFF Architecture and Implementation

Core MLFF Components and Properties

Table 1: Comparative Analysis of Force Field Methodologies

| Property | Molecular Mechanics (MM) | Machine Learning Force Fields (MLFF) |

|---|---|---|

| Genesis | McCammon, Gelin, and Karplus (1977) | Behler and Parrinello (2007) |

| Runtime Complexity | 𝒪(N) | 𝒪(N) |

| Simulation Speed | >1μs/day | ~1 ns/day |

| Accuracy | >1 kcal/mol | <<1 kcal/mol for small molecules |

| Invariance | E(3) | E(3) |

| Equivariant Universality | Impossible | Possible |

| Stability | Usually guaranteed | Not guaranteed |

| Force Differentiation | Analytical | Autograd |

| Parametrization | Human-derived | Automated [26] |

Key Architectural Approaches

Modern MLFF architectures employ sophisticated geometric learning principles to capture quantum mechanical interactions:

Equivariant Message Passing Networks: SO(3)-equivariant architectures utilize tensor products within convolution operations to incorporate directional information, enabling discrimination of interactions that appear inseparable to simpler models. These models capture interactions depending on the relative orientation of neighboring atoms, learning more transferable interaction patterns from training data [27].

Euclidean Transformers: Novel approaches like SO3krates combine sparse equivariant representations with self-attention mechanisms that separate invariant and equivariant information, eliminating the need for expensive tensor products. This architecture achieves a unique combination of accuracy, stability, and speed, enabling stable MD trajectories for flexible peptides and supramolecular structures with hundreds of atoms [27].

Global Representation Models: BIGDML employs a global atomistic representation with periodic boundary conditions that avoids the locality approximation and artificial atom-type assignment. By using the full translation and Bravais symmetry group for a given material, this approach achieves meV/atom accuracy with just 10-200 training geometries while capturing long-range interactions [28].

Diagram: MLFF Computational Workflow showing the transformation from atomic coordinates to forces via symmetry-aware processing.

Technical Support: Troubleshooting Common MLFF Implementation Issues

Training Instability and Divergence

Problem: During on-the-fly training, MLFF simulations become unstable, leading to unphysical configurations or divergent energy values.

Root Causes:

- Inadequate sampling of phase space during training

- Poorly converged electronic structure calculations

- Incorrect force matching thresholds

- Insufficient training data for complex molecular interactions

Solutions:

- Gradually heat the system during training, starting with low temperature and increasing to about 30% above the desired application temperature to explore larger phase space regions [29].

- Prefer molecular dynamics training runs in the NpT ensemble (ISIF=3) when possible, as additional cell fluctuations improve force field robustness [29].

- For systems containing surfaces or isolated molecules, set stress weights (ML_WTSIF) to very small values (e.g., 1E-10) since vacuum-terminated systems don't exert meaningful stress on the simulation cell [29].

- Adjust the default value of ML_CTIFOR (typically 0.02) to lower values if insufficient reference configurations are being captured during training [29].

Poor Transferability and Generalization

Problem: MLFFs trained on specific molecular configurations fail to generalize to related but distinct molecular systems or different regions of phase space.

Root Causes:

- Limited chemical diversity in training data

- Overfitting to specific conformational states

- Inadequate representation of long-range interactions

- Missing critical molecular environments in training set

Solutions:

- For systems with multiple components, train subsystems separately before combining. For example, train crystal surfaces, isolated molecules, and bulk materials independently before simulating the complete system [29].

- Treat atoms of the same element in different chemical environments as separate species within the MLFF, particularly when atoms have different oxidation states or local environments (e.g., surface vs bulk atoms) [29].

- Implement iterative retraining cycles using ML_MODE=SELECT to reselect local reference configurations from existing ab-initio data, creating updated force fields with improved coverage [29].

- Utilize global representation schemes like BIGDML that avoid artificial atom-type assignment and capture long-range correlations between atomic species [28].

Computational Performance Bottlenecks

Problem: MLFF simulations run significantly slower than traditional molecular mechanics, limiting practical application to large biomolecular systems.

Root Causes:

- Expensive tensor operations in equivariant architectures

- Inefficient neighbor list management

- Excessive model complexity for target accuracy

- Suboptimal hardware utilization

Solutions:

- Implement Euclidean self-attention mechanisms (e.g., SO3krates) that replace SO(3) convolutions with orientation filters, eliminating need for expensive tensor products while maintaining equivariance [27].

- For systems with many atomic species, utilize reduced descriptors (MLDESCTYPE=1) to achieve linear scaling with number of species rather than quadratic scaling [29].

- Balance model complexity with application requirements—higher equivariant representation degrees (lmax) improve accuracy but scale computational cost as lmax^6 [27].

- Consider hybrid approaches that combine MLFF accuracy with MM speed for less critical interaction regions.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the key differences between traditional force fields and MLFFs?

Traditional molecular mechanics force fields use fixed functional forms with human-derived parameters, achieving high speed but limited accuracy (>1 kcal/mol). MLFFs utilize flexible neural network functionals trained on ab initio data, achieving quantum-mechanical accuracy (<1 kcal/mol) but with higher computational cost. MLFFs automatically capture complex many-body interactions without predefined functional forms, while MM force fields rely on predetermined bonding and non-bonding interaction terms [26].

Q2: How much training data is typically required to develop a reliable MLFF?

Data requirements vary significantly by methodology. Global representation models like BIGDML can achieve meV/atom accuracy with just 10-200 training geometries for periodic materials by leveraging physical symmetries [28]. Atom-centered approaches typically require thousands of configurations for similar accuracy. Data efficiency is dramatically improved by incorporating physical constraints like energy conservation and relevant symmetries, reducing the complexity of the data manifold that must be learned [28].

Q3: What are the most common causes of instability in MLFF molecular dynamics simulations?

Instability primarily arises from poor extrapolation behavior when simulations explore configurations significantly different from training data distribution. This is particularly problematic for high-temperature configurations or conformationally flexible structures. Equivariant representations demonstrate improved robustness to cumulative inaccuracies and better extrapolation to higher temperatures compared to invariant models [27]. Ensuring comprehensive phase space coverage during training and using stochastic thermostats like Langevin dynamics improve stability [29].

Q4: How can I handle different chemical environments for the same atomic species?

Atoms of the same element in different chemical environments (e.g., different oxidation states, surface vs bulk atoms) should be treated as separate species within the MLFF. In the POSCAR file, arrange atoms by "subtype" with distinct names (e.g., "O1", "O2") and update the POTCAR file accordingly with separate entries for each species. This approach significantly improves accuracy but increases computational cost, which scales quadratically with the number of species (reduced to linear scaling with MLDESCTYPE=1) [29].

Q5: What is the significance of equivariance in MLFF architectures?

Equivariance ensures that model predictions transform consistently with molecular rotations and translations, a fundamental physical symmetry. Equivariant models incorporate directional information beyond pairwise distances, enabling them to discriminate between interaction patterns that appear identical to invariant models. This results in better data efficiency, improved extrapolation behavior, and lower error distribution spread, ultimately leading to more stable MD simulations [27].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

MLFF Training Workflow

Table 2: MLFF Training Configuration Parameters

| Parameter | Recommended Setting | Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| ML_MODE | TRAIN | Initiates training mode |

| ML_CTIFOR | 0.02 (adjust as needed) | Controls configuration selection threshold |

| ML_WTSIF | 1E-10 (for surfaces/molecules) | Stress weight for vacuum-terminated systems |

| ISIF | 3 (NpT ensemble) | Enables cell fluctuations for robustness |

| ISYM | 0 | Disables symmetry for MD |

| Thermostat | Langevin | Improves phase space sampling |

| POTIM | ≤0.7 fs (H), ≤1.5 fs (O), ≤3 fs (heavy) | Integration time step for stability [29] |

Diagram: MLFF Development Cycle showing iterative training and validation process.

Advanced Training Protocol: Multi-Stage System Assembly

For complex systems like drug-target binding interfaces:

Component Isolation: Train separate MLFFs for protein backbone, side chains, ligand molecules, and solvent environment using targeted ab-initio calculations for each component [29].

Subsystem Integration: Combine trained component MLFFs, focusing additional training on interfacial regions where components interact. Use constrained dynamics to maintain reasonable configurations during initial training phases.

Full System Refinement: Conduct production training on the complete assembled system, using the pre-trained component MLFFs as initialization to significantly reduce required ab-initio calculations [29].

Validation Against Experimental Data: Compare simulation outcomes with available experimental data (e.g., NMR constraints, crystallographic B-factors) to identify regions requiring additional training.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Computational Tools

Table 3: MLFF Development and Deployment Tools

| Tool Category | Representative Solutions | Primary Function |

|---|---|---|

| MLFF Architectures | SO3krates, BIGDML, MPNICE | Specialized neural networks for force field development |

| Molecular Dynamics Engines | Desmond, VASP, LAMMPS | Production MD simulation with MLFF support |

| Ab-initio Reference | DFT, CASSCF, MP2 | Generate training data with quantum accuracy |

| System Preparation | MS Maestro, PACKMOL | Build complex molecular systems for simulation |

| Analysis & Visualization | MDTraj, VMD, PyMOL | Analyze trajectories and visualize results |

| Training Frameworks | TensorFlow, PyTorch, JAX | Implement and optimize custom MLFF architectures [30] |

Successful MLFF deployment requires careful attention to both theoretical foundations and practical implementation details. Researchers should prioritize comprehensive phase space sampling during training, utilize appropriate symmetry-aware architectures for their specific systems, and implement robust validation protocols against both quantum mechanical and experimental data. While current MLFF implementations achieve unprecedented accuracy for molecular simulations, ongoing architectural innovations continue to address limitations in computational speed, stability, and generalizability. By adhering to the troubleshooting guidelines and methodological frameworks presented in this technical support center, researchers can effectively leverage MLFF technology to advance drug development and materials discovery with quantum-accurate molecular dynamics simulations.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My MLFF produces unstable molecular dynamics (MD) trajectories for Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), leading to significant volume drift. What could be the cause and how can I address it?

Instability in MD trajectories, particularly volume drift, often indicates that the force field struggles to generalize to the diverse and complex chemistries found in MOFs. This is a known challenge, and benchmark results from MOFSimBench can guide you toward more robust models.

- Solution: Consider using a universal MLIP that has demonstrated high stability on MOFs. According to MOFSimBench evaluations, models like eSEN-OAM, PFP, and orb-v3-omat+D3 were top performers in the MD stability task, successfully maintaining stable volumes (change <10%) in NPT simulations for a high number of structures [31]. Ensuring your model was trained on diverse data that includes out-of-equilibrium conformations is also critical for robustness [32].

Q2: The bulk modulus predicted by my MLFF for a nanoporous material deviates significantly from the DFT reference value. Which models are known to accurately predict such mechanical properties?

The accurate prediction of bulk properties like the bulk modulus is a stringent test for an MLFF. It requires the model to correctly capture the response of the material to strain.

- Solution: Benchmarking data shows that specific universal MLIPs excel at this task. For the bulk modulus calculation on MOFs, eSEN-OAM achieved the lowest Mean Absolute Error (MAE), followed by PFP, which also showed a very high success rate (98 out of 100 structures) in the calculation itself [31]. Using a model that includes dispersion correction (e.g., D3) is also essential for accurately capturing the interactions in porous materials [31].

Q3: How can I assess the ability of an MLFF to describe host-guest interactions, which are critical for adsorption applications in MOFs?

Host-guest interaction energy is a key property for applications like carbon capture. Specialized benchmarks now evaluate this specific task.

- Solution: Evaluate your model on a dedicated host-guest interaction task, such as the one in MOFSimBench that uses data from the GoldDAC database. This assesses the model's performance on the energy and forces of CO₂ and H₂O interacting with various MOFs [31]. The benchmark results indicate that while some models fine-tuned on specific datasets (like MACE-DAC-1+D3) perform well, universal models like PFP and eSEN-OAM also demonstrate strong and consistent performance across different interaction regimes (repulsion, equilibrium, and weak-attraction) [31].

Q4: My system is a large supramolecular complex (over 300 atoms). Are there global MLFFs that can handle such systems without introducing localization approximations?

Traditional global MLFFs have been limited to small systems, but recent methodological advances have broken this barrier.

- Solution: The symmetric Gradient Domain Machine Learning (sGDML) framework has been extended to create accurate global force fields for molecules with hundreds of atoms. This approach avoids locality assumptions, ensuring all atomic degrees of freedom remain fully correlated, which is crucial for describing systems with long-range interactions [33] [34]. This capability has been demonstrated on the MD22 benchmark dataset, which includes supramolecular complexes like the "buckyball-catcher" (up to 370 atoms) [33] [35].

Q5: How can I improve the robustness and training efficiency of my MLFF, especially for simulating rare events like ion diffusion in solid electrolytes?

Standard data-driven MLFFs can fail for rare, high-energy events not represented in the training data, leading to unphysical results like atom clustering in long-time MD simulations [36].

- Solution: A promising strategy is to incorporate physical constraints via a hybrid framework. You can integrate an empirical short-range repulsive potential, such as the Ziegler-Biersack-Littmark (ZBL) potential, with your MLFF. This hybrid approach provides a physically correct barrier against unphysical atomic overlap, preventing simulation breakdowns. This method has been shown to significantly improve robustness and reduce the need for extensive active learning, achieving good performance with as few as 25 training configurations for a complex solid electrolyte (LLZO) [36].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Inaccurate Structure Optimization

This occurs when the MLFF fails to predict the correct equilibrium geometry of a material.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Compare the optimized volume (or lattice parameters) from your MLFF relaxation with the DFT-relaxed structure.

- Calculate the volume change rate,

ΔV = 1 - V_MLFF / V_DFT. A deviation of more than ±10% is typically considered a failure for MOF systems [31].

Resolution Steps:

- Switch to a higher-performing model: As per MOFSimBench, the best-performing models for structure optimization of MOFs were PFP, orb-v3-omat+D3, eSEN-OAM, and uma-s-1p1 [31].

- Verify dispersion corrections: Ensure your model includes an appropriate treatment of dispersion forces (e.g., D3 correction), which are critical for the stability of porous materials [31].

- Check the training data diversity: If you are training your own model, ensure the training set encompasses a wide variety of chemical environments and structural deformations [32].

Issue: Poor Prediction of Thermal Properties (e.g., Heat Capacity)

The MLFF-derived heat capacity (Cv) does not agree with reference DFT calculations.

Diagnosis Steps:

- Perform a phonon calculation using the force constants obtained from your MLFF.

- Compare the resulting Cv at your target temperature (e.g., 300 K) with the DFT reference value.

Resolution Steps:

- Select a model with proven accuracy for thermal properties: For heat capacity prediction on MOFs, models like PFP, orb-v3-omat+D3, and uma-s-1p1 have demonstrated low prediction errors [31].

- Ensure accurate force predictions: Heat capacity is derived from the vibrational modes, which depend on the forces. A model with low force errors is a prerequisite. The sGDML model, for instance, is trained specifically on forces and has shown excellent performance for complex molecules [33] [34].

Benchmarking Data and Performance Tables

The following tables summarize key quantitative results from recent benchmarks to aid in model selection.

Table 1: Performance of Selected MLIPs on MOFSimBench Tasks (Data sourced from [31])

| Model | Structure Optimization (Structures within ±10% ΔV) | MD Stability (Structures within ±10% ΔV) | Bulk Modulus (MAE [GPa]) / Success Rate | Heat Capacity (MAE [J/mol/K]) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PFP | 92 / 100 | 86 / 100 | 2.8 / 98% | 4.5 |

| eSEN-OAM | 89 / 100 | 90 / 100 | 2.4 / 94% | 6.2 |

| orb-v3-omat+D3 | 90 / 100 | 87 / 100 | 3.3 / 92% | 4.3 |

| uma-s-1p1 | 89 / 100 | Not Tested | 3.1 / 98% | 4.5 |

| MACE | 85 / 100 | 83 / 100 | 4.6 / 93% | 6.9 |

Table 2: Overview of Key MLFF Benchmark Datasets

| Dataset | System Types | System Size | Key Properties Measured | Primary Use Case |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOFSimBench [31] [32] | Metal-Organic Frameworks (MOFs), COFs, Zeolites | Varies (benchmark: 100 diverse structures) | Structure optimization, MD stability, Bulk modulus, Heat capacity, Host-guest interactions | Evaluating MLFFs for nanoporous materials |

| MD22 [33] [34] [35] | Biomolecules, Supramolecular complexes | 42 to 370 atoms | Energy, Forces (for global MD trajectories) | Evaluating global MLFFs on large, complex molecules |

| SAMD23 [37] | Semiconductor materials (Si₃N₄, HfO₂) | Varies | Energy, Forces, Simulation-derived metrics | Benchmarking MLFFs for semiconductor applications |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Running a MOFSimBench-style Structure Optimization Benchmark

Objective: To evaluate an MLFF's ability to correctly relax the atomic coordinates and cell geometry of a diverse set of MOF structures.

Materials (Research Reagents):

- Software: An atomistic simulation environment (e.g., ASE, LAMMPS) with the MLFF model integrated.

- Structures: A set of 83 MOF, 7 COF, and 10 zeolite initial structures, as used in MOFSimBench [31] [32].

- Reference Data: DFT-optimized structures for the same set (e.g., using PBE functional with D3 dispersion correction) [31].

Methodology:

- Input: For each structure in the benchmark set, use the initial unoptimized configuration.

- Relaxation: Perform a full structure optimization (both atomic positions and unit cell) using the MLFF to evaluate.

- Calculation: Use a standard DFT calculator with PBE+D3 to relax the same initial structures. These are the reference values.

- Analysis: For each structure, calculate the volume change rate:

ΔV_DFT = 1 - (V_MLFF / V_DFT). Count the number of structures where the absolute value ofΔV_DFTis less than 10% [31].

Protocol 2: Validating Host-Guest Interaction Energies

Objective: To assess an MLFF's accuracy in predicting the interaction energy between a MOF host and a gas molecule (e.g., CO₂).

Materials (Research Reagents):

- Software: DFT code (e.g., VASP, FHI-aims) and MLFF simulation environment.

- Structures: 26 MOF structures with adsorbed CO₂ molecules at different reaction coordinates (Repulsion, Equilibrium, Weak-attraction) from the GoldDAC database [31].

Methodology:

- Single-point Calculations: For each host-guest system, perform a single-point energy calculation using both the MLFF and DFT.

- Reference Calculations: Perform separate single-point calculations for the isolated MOF host and the isolated gas molecule using both methods.

- Energy Calculation: Compute the interaction energy as: