Harnessing Nature's Tiny Factories

The Engineered Exploitation of Microbial Potential

Explore the ScienceMore Than Just Germs: The Invisible Power of Microbes

In the intricate world of microorganisms, invisible factories are operating at full capacity, producing everything from life-saving medicines to sustainable biofuels.

These microscopic powerhouses—bacteria, yeasts, and other single-celled organisms—have been harnessed by humans for millennia through traditional practices like baking and brewing. Today, however, we're witnessing a revolutionary shift: instead of merely utilizing what microbes naturally produce, scientists are now engineering them to perform specific tasks with unprecedented precision 1 6 9 .

Living Therapeutics

Engineered bacteria can serve as living therapeutics that sense inflammation in the gut and deliver targeted treatment exactly where needed 6 .

Sustainable Solutions

Engineered microorganisms are being deployed to break down pollutants, valorize waste into useful products, and produce bioenergy from renewable resources 9 .

This new frontier of microbiome engineering represents a convergence of biology, technology, and innovation. Researchers are designing custom microbial communities that can fight diseases, clean up environmental pollutants, transform waste into valuable resources, and produce sustainable alternatives to petroleum-based products.

The Science of Microbial Engineering: From Manipulation to Creation

What is Microbial Engineering?

Microbial engineering is the practice of deliberately modifying microorganisms to enhance their natural capabilities or equip them with entirely new functions. This field moves beyond traditional fermentation—where microbes naturally transform substances—to intentional genetic and metabolic redesign. Scientists are essentially rewriting microbial DNA to create specialized microorganisms that perform tasks with exceptional efficiency or produce valuable compounds that wouldn't exist naturally 6 .

The Engineering Framework: Design-Build-Test-Learn

To systematically harness microbial potential, scientists follow an iterative framework known as the Design-Build-Test-Learn (DBTL) cycle. This engineering approach has been successfully adapted from other disciplines to create a structured process for developing effective microbial solutions 8 .

Design

Researchers determine the specific genetic modifications needed to achieve desired microbial functions. This phase involves two primary approaches:

- Top-down design: Manipulating environmental conditions to shape entire microbial communities through natural selection

- Bottom-up design: Designing metabolic networks at the molecular level and assembling custom microbial communities with predictable interactions 8

Build

This stage involves physically implementing the genetic designs using sophisticated tools like CRISPR-Cas9 gene editing. Scientists modify microbial DNA to introduce new capabilities or enhance existing ones, creating strains that can perform specialized functions such as producing therapeutic compounds or breaking down toxic substances 1 6 .

Test

The engineered microbes are rigorously evaluated to determine how well they perform their intended functions under controlled conditions. Researchers measure key indicators like compound production yields, therapeutic effectiveness, or pollutant degradation rates 8 .

Learn

Data from testing phases are analyzed to refine understanding of microbial behavior and improve subsequent designs. This continuous learning process allows scientists to address challenges and enhance performance through multiple DBTL iterations 8 .

| Approach | Methodology | Best For | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Top-Down | Manipulating environmental conditions to shape microbial communities through selection | Complex systems where individual interactions are not fully understood | Wastewater treatment, bioremediation |

| Bottom-Up | Designing metabolic networks at molecular level and assembling custom communities | Applications requiring precise control over specific functions | Producing high-value compounds, specialized therapeutics |

Table 1: Microbial Engineering Approaches Compared

A Closer Look: Unraveling Antibiotic Resistance

The Experiment That Revealed a New Mechanism

In 2025, an international team of scientists from the John Innes Centre and collaborating institutions made a critical breakthrough in understanding how bacteria develop antibiotic resistance—one of the most pressing public health threats of our time. Their curiosity-driven research focused on a model plasmid called RK2, a small DNA molecule that exists independently within bacterial cells and carries genes for antibiotic resistance 7 .

Methodology and Surprising Discovery

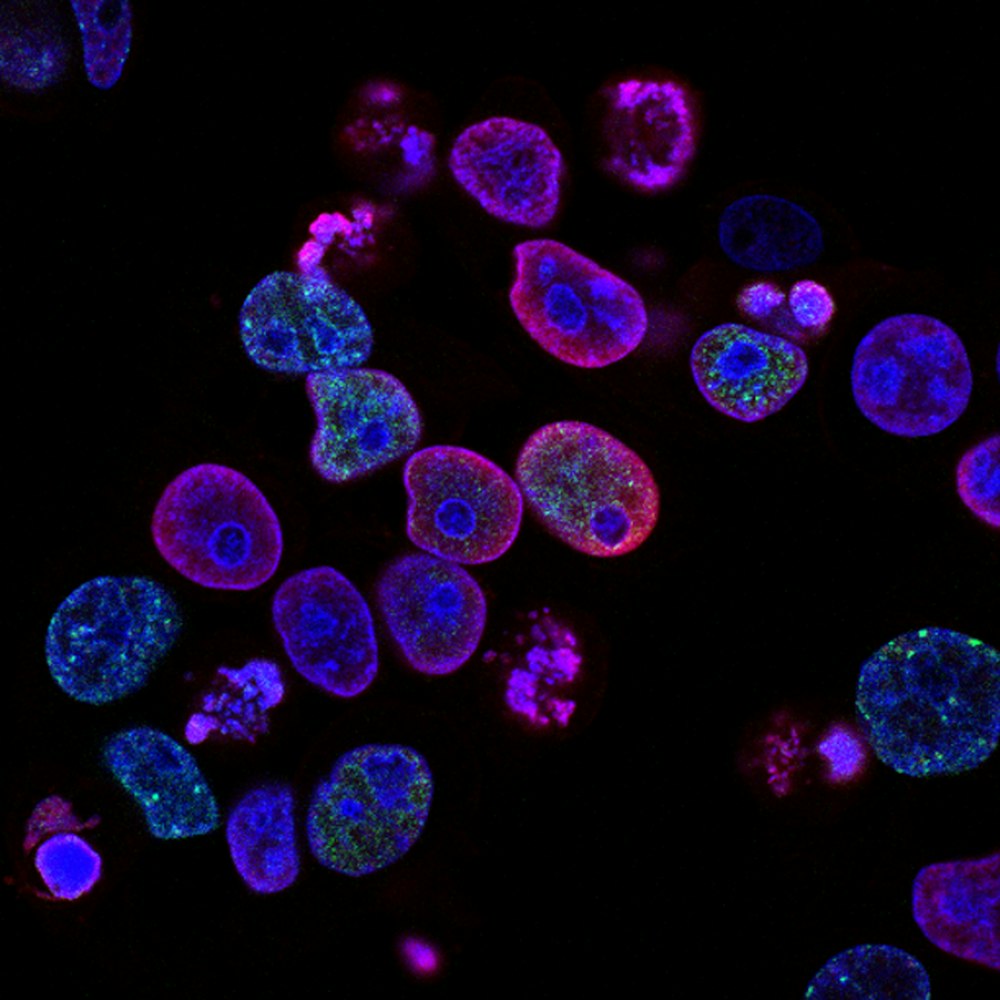

The research team employed advanced microscopy and protein crystallography techniques to examine the structure and function of KorB at the molecular level. These sophisticated tools allowed them to visualize how proteins interact with DNA and with each other in exquisite detail 7 .

"The turning point came unexpectedly during what the lead researcher Dr. Thomas McLean described as a lucky 'Friday afternoon experiment' conducted purely out of curiosity." 7

Their investigation revealed something unexpected: KorB doesn't work alone. Instead, it forms a complex with another molecule called KorA. The researchers discovered that KorB acts as a DNA sliding clamp that moves along the bacterial DNA, while KorA serves as a lock that holds KorA in place at specific genetic locations. Together, this protein complex effectively shuts off gene expression in ways that help the plasmid survive within its bacterial host 7 .

| Research Aspect | Previous Understanding | New Discovery | Significance |

|---|---|---|---|

| KorB Function | DNA-binding protein involved in gene expression control | Acts as a DNA sliding clamp that moves along genetic material | Reveals new mechanism of genetic regulation |

| KorA Function | Known plasmid protein with unclear function | Serves as lock that positions and stabilizes KorB | Demonstrates cooperative protein interaction |

| Gene Regulation | Short-range gene control understood | Long-range gene silencing capability discovered | Explains how distant genes can be simultaneously controlled |

Table 2: Key Findings from the KorB-KorA Antibiotic Resistance Study

Implications and Future Directions

This discovery provides a new paradigm for understanding how bacteria control gene expression over long genetic distances. The implications extend far beyond academic interest, as this knowledge offers a potential target for novel therapeutics that could destabilize plasmids in their bacterial hosts. If scientists can develop drugs that disrupt the KorB-KorA interaction, they might be able to re-sensitize drug-resistant bacteria to existing antibiotics, restoring the effectiveness of our current antimicrobial arsenal 7 .

Antibiotic Resistance Research Timeline

The Microbial Engineer's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Engineering microorganisms requires specialized tools and materials that enable scientists to modify, grow, and analyze microbial systems.

| Reagent/Material | Primary Function | Application in Microbial Engineering |

|---|---|---|

| Agar | Gelatinous growth medium providing nutrients and stable environment | Culturing microorganisms in petri dishes for observation and experimentation |

| CRISPR-Cas Systems | Precise gene editing tools | Modifying specific microbial genes to enhance or create new functions |

| Antibiotics | Selection agents | Identifying successfully engineered microbes by eliminating unmodified ones |

| IPTG | Chemical inducer of gene expression | Activating engineered genetic circuits in microbial hosts during experiments |

| Polyethyleneimine (PEI) | Transfection reagent | Introducing foreign DNA into microbial cells for genetic modification |

| Biotinyl Tyramide | Signal amplification agent | Enhancing detection of microbial components or products in diagnostic applications |

| L-Azidohomoalanine | Unnatural amino acid | Bio-orthogonal labeling of newly synthesized proteins to track microbial activity |

| Plasmids (e.g., RK2) | Small DNA molecules independent of chromosomal DNA | Studying antibiotic resistance mechanisms and developing genetic engineering tools |

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents in Microbial Engineering

Genetic Tools

Precise editing with CRISPR and plasmid vectors

Culture Media

Nutrient-rich environments for microbial growth

Analysis Methods

Advanced microscopy and protein crystallography

Beyond the Lab: The Future of Engineered Microbes

Living Medicines and Sustainable Solutions

The implications of microbial engineering extend far beyond laboratory curiosity, with revolutionary applications already in development across multiple fields. In medicine, researchers are creating "smart" living therapeutics for conditions like inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). These engineered symbiotic bacteria, yeasts, and bacteriophages can sense pathological signals and deliver targeted treatments directly where needed 6 .

Medical Applications

- Targeted drug delivery systems

- Real-time disease monitoring

- Personalized medicine approaches

- Reduced side effects

Environmental Solutions

- Waste valorization

- Pollution cleanup

- Biofuel production

- Circular bioeconomy

This approach offers significant advantages over conventional medicines. Engineered bacteria can localize to specific sites of inflammation within the gut, areas often difficult to reach effectively with systemic drugs. This targeted action minimizes side effects and improves safety profiles. As living therapeutics, these microbes can sense and respond to dynamic physiological changes, providing real-time monitoring of disease activity and treatment response 6 .

Challenges and Ethical Considerations

Despite the exciting potential, microbial engineering faces significant challenges that researchers must address before widespread application. Key hurdles include ensuring the safety and long-term stability of genetically modified organisms within complex ecosystems, addressing concerns about horizontal gene transfer to natural populations, and establishing appropriate regulatory frameworks for these novel technologies 6 8 .

Technical Challenges

Genetic Stability Predictable Behavior Scalability ContainmentEthical Considerations

Biosafety Regulation Public Acceptance Environmental Impact| Application Area | Current Uses | Future Potential | Key Microbial Products |

|---|---|---|---|

| Medicine | Probiotics, basic biotherapeutics | Intelligent living diagnostics and targeted drug delivery systems | Anti-inflammatory molecules, therapeutic proteins, sensing circuits |

| Agriculture | Soil amendments, basic fertilizers | Engineered microbial communities for enhanced crop protection and growth | Biofertilizers, biopesticides, stress-resistance promoters |

| Industry | Traditional fermentation for food production | Sustainable production of chemicals, materials, and energy from waste streams | Biofuels, biodegradable plastics, platform chemicals |

| Environment | Basic wastewater treatment | Advanced bioremediation of contaminated sites and carbon capture | Degradation enzymes, metal-sequestering molecules, carbon-fixing systems |

Table 4: Promising Applications of Engineered Microbes

Our Microbial Future: Engineering a Symbiotic Relationship

As we advance our ability to engineer the microbial world, we're forging a new partnership with the invisible organisms that share our planet. The engineered exploitation of microbial potential represents not just a technological revolution, but a fundamental shift in how humanity interacts with the natural world. These tiny biological powerhouses offer sustainable solutions to global challenges in healthcare, environmental sustainability, and industrial production.