Decoding Molecules: AI-Driven Advances in Structure-Property Relationships for Drug Discovery

This article comprehensively explores the evolving landscape of molecular structure-property relationships, a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and materials science.

Decoding Molecules: AI-Driven Advances in Structure-Property Relationships for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article comprehensively explores the evolving landscape of molecular structure-property relationships, a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and materials science. We examine the fundamental principles connecting molecular structure to biological activity and physicochemical properties, then delve into the transformative impact of artificial intelligence and deep learning methodologies. The content addresses critical methodological challenges, including data scarcity and model interpretability, by presenting advanced optimization strategies like few-shot learning and multi-modal integration. Finally, we provide a rigorous validation framework comparing model performance across benchmarks and real-world applications, offering researchers and drug development professionals a practical guide to leveraging these technologies for accelerated and more reliable molecular property prediction.

The Fundamental Blueprint: How Molecular Structure Dictates Properties and Activity

Core Principles of Structure-Activity Relationships (SAR) in Drug Design

The Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR) is a fundamental concept in medicinal chemistry and drug design, defined as the relationship between the chemical structure of a molecule and its biological activity [1]. This principle, first articulated by Alexander Crum Brown and Thomas Fraser as early as 1868, posits that the physiological action of a substance is intrinsically linked to its chemical composition [1] [2]. In modern drug discovery, SAR analysis is the systematic process of identifying the chemical groups responsible for eliciting a target biological effect and using this information to modify the effect or potency of a bioactive compound [1] [3]. The primary goal of SAR studies is to guide the rational exploration of chemical space, which is essentially infinite without the "sign posts" provided by such relationships [4]. By understanding how specific structural modifications influence biological activity, medicinal chemists can optimize multiple physicochemical and biological properties simultaneously—such as improving potency, reducing toxicity, and ensuring sufficient bioavailability—during lead optimization phases [4] [5].

The development of a drug from initial concept to marketed product is a complex endeavor that can span 12-15 years and cost over $1 billion [5]. Throughout this process, SAR principles are applied at multiple stages, ranging from primary screening to lead optimization. The ability to rapidly identify and elucidate SAR trends allows research teams to prioritize the most promising chemical series from hundreds of potential candidates, especially when faced with large-scale high-throughput screening data [4]. Traditionally, SAR was developed by synthesizing a series of structurally related chemical compounds and testing each one to determine its pharmacological activity [2]. For instance, the development of β-adrenergic antagonists (antihypertensive drugs) and β₂ agonists (asthma drugs) involved making minor modifications to the chemical structure of the naturally occurring agonists epinephrine and norepinephrine [2]. Over time, as data from compound series accumulated, medicinal chemists developed understanding of which chemical substitutions would produce agonists versus antagonists, and which modifications would improve metabolic stability or duration of action [2].

Foundational SAR Concepts and Terminology

Key Definitions and Scope

- Structure-Activity Relationship (SAR): The relationship between a compound's chemical structure and its biological activity, enabling determination of chemical groups responsible for evoking target biological effects [1] [3].

- Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR): A mathematical refinement of SAR that creates quantitative relationships between chemical structure and biological activity, developed in the 1960s to simplify the search for chemical structures that activate or block drug receptors [4] [1] [2].

- Structure-Property Relationship (SPR): A broader term encompassing relationships between chemical structure and any property of interest, not limited to biological activity [6] [7].

- Chemical Space: The conceptual space encompassing all possible organic molecules, which is essentially infinite without SAR guidance [4].

- Lead Optimization: The process where SAR understanding is applied to make structural modifications that optimize multiple properties of a lead compound simultaneously [4] [5].

The SAR Table: A Fundamental Tool

SAR is typically evaluated in a structured table format known as an SAR table, which systematically presents compounds alongside their physical properties and biological activities [3]. Experts review these tables by sorting, graphing, and scanning structural features to identify potential relationships and trends that inform subsequent compound design [3]. This systematic approach allows for the recognition of which structural characteristics correlate with chemical and biological reactivity, enabling conclusions about uncharacterized compounds based on their structural features [3].

Table 1: Core Terminology in SAR Research

| Term | Definition | Primary Application |

|---|---|---|

| SAR | Qualitative relationship between chemical structure and biological activity | Early-stage lead identification and optimization |

| QSAR | Mathematical quantification of structure-activity relationships | Predictive modeling and quantitative property optimization |

| Domain of Applicability | The chemical space where a QSAR model provides reliable predictions | Model validation and appropriate application of predictive tools |

| Structure-Affinity Relationship (SAFIR) | Relationship focusing specifically on binding affinity | Target engagement optimization |

| Structure-Biodegradability Relationship (SBR) | Relationship between structure and environmental biodegradability | Environmental risk assessment [1] |

Methodological Framework for SAR Exploration

Experimental Approaches to SAR Development

The exploration of SAR relies on a combination of experimental and computational methodologies. The classical approach involves systematic structural modification followed by biological testing to establish correlations.

SAR Through Analog Synthesis

The traditional method for establishing SAR involves synthesizing a series of structural analogs and testing their biological activities [2]. This process follows a systematic workflow:

- Identify a lead compound with desirable but suboptimal activity

- Design analogs with specific structural modifications

- Synthesize the analog series

- Test biological activity across relevant assays

- Analyze results to identify structural trends correlated with activity

- Iterate with new designs based on emerging patterns

This approach was successfully used in developing early drugs like arsphenamine (the first syphilis treatment) and later with β-adrenergic drugs [2]. The strength of this method lies in its direct experimental validation, though it can be time-consuming and resource-intensive.

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) and SAR

Modern drug discovery often employs high-throughput screening (HTS), where hundreds of thousands of compounds can be tested in automated systems [4] [5]. When facing hundreds of chemical series from primary HTS, SAR analysis becomes crucial for identifying the most promising series for further investigation [4]. The challenge with HTS-based SAR is managing the vast data generated and distinguishing true structure-activity trends from random noise.

Combinatorial Chemistry Approaches

Combinatorial chemistry represents a significant advancement in SAR exploration, enabling the parallel synthesis of hundreds to thousands of compounds [2]. Unlike traditional linear synthesis, where building blocks are assembled step-wise, combinatorial chemistry reacts multiple building blocks (e.g., A₁-A₅) with other sets (B₁-B₅ and C₁-C₅) in parallel, potentially generating 125 compounds from just 15 building blocks [2]. When combined with robotic synthesis, this approach allows medicinal chemists to prepare hundreds of thousands of compounds in significantly less time than traditional methods, dramatically accelerating SAR exploration [2].

Computational Approaches to SAR

Computational methods have become indispensable for modern SAR analysis, particularly when dealing with large datasets generated by high-throughput experimental techniques [4].

QSAR Modeling Methodologies

QSAR methodologies can be broadly divided into two groups: those based on statistical or data mining methods (e.g., regression models) and those based on physical approaches (e.g., pharmacophore models) [4]. The choice of modeling technique significantly influences how extensively and in what detail an SAR can be explored.

Table 2: Comparison of QSAR Modeling Approaches

| Model Type | Description | Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| 2D QSAR | Uses molecular descriptors derived from 2D structures | Fast calculation, well-established | May miss stereochemical effects [4] |

| 3D QSAR | Incorporates three-dimensional structural information | Captures steric and electrostatic effects | More computationally intensive |

| Pharmacophore Modeling | Identifies spatial arrangement of features essential for activity | Highly interpretable, directly informs design | Dependent on alignment rules |

| Machine Learning-based QSAR | Uses non-linear algorithms (NN, SVM, RF) | High accuracy, handles complex relationships | Potential "black box" character [4] [6] |

Statistical QSAR approaches link chemical structure (characterized by numerical descriptors) to biological activities through various algorithms, ranging from traditional linear regression to modern non-linear methods like neural networks and support vector machines [4]. The latter often exhibit higher accuracy as they don't assume linear relationships, which is important given the complex biological systems being modeled [4].

Explainable AI and SAR Interpretation

A significant challenge in computational SAR is the interpretability of models. While machine learning models can achieve high predictive accuracy, their "black box" nature often limits trust among experimental chemists [6]. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) is an emerging field that addresses this opacity by providing rationales for model predictions [6]. Recent approaches, such as the XpertAI framework, integrate XAI methods with large language models (LLMs) to generate natural language explanations of structure-property relationships from raw chemical data [6]. These developments are critical for increasing trust in ML models and expanding the possibilities of computational SAR exploration.

Domain of Applicability: Ensuring Model Reliability

A crucial consideration in SAR modeling is defining the domain of applicability (DA)—the chemical space where the model's predictions can be considered reliable [4]. All QSAR approaches assume that new molecules to be predicted have structural features in common with the training set; if a new molecule is sufficiently different, predictions become unreliable or meaningless [4]. Simple approaches to define DA include measuring the similarity of a new molecule to its nearest neighbor in the training set or counting the number of nearest neighbors within a user-defined similarity cutoff [4]. More sophisticated approaches use descriptor value ranges or principal component analysis to define the applicable chemical space [4].

Experimental Protocols for SAR Determination

Guidelines for Reporting SAR Experiments

Proper experimental protocol reporting is essential for reproducibility and meaningful SAR interpretation. Based on analysis of over 500 published and unpublished experimental protocols, key data elements should include [8]:

- Clear objective and hypothesis

- Detailed chemical structures and synthesis procedures

- Reagent specifications including sources, catalog numbers, and lot numbers

- Equipment details with manufacturers and settings

- Step-by-step workflow with precise parameters

- Experimental conditions including temperature, timing, and environmental controls

- Data collection methods and instrumentation

- Quality controls and validation steps

- Data analysis procedures

- Troubleshooting guidance

Ambiguous reporting such as "store at room temperature" or generic reagent descriptions (e.g., "Dextran sulfate, Sigma-Aldrich") should be avoided, as variations in these factors can significantly impact results and SAR interpretation [8].

Target Identification and Validation Protocols

SAR studies begin with well-validated biological targets. The target identification and validation process includes [5]:

- Data mining of biomedical literature and databases

- Gene expression analysis to correlate target expression with disease

- Genetic association studies identifying links between polymorphisms and disease risk

- Phenotypic screening to identify disease-relevant targets

- Antisense technology using modified oligonucleotides to block target protein synthesis

- Transgenic animal models including knockouts and knock-ins

- RNA interference for targeted gene silencing

- Monoclonal antibodies for highly specific target modulation

- Chemical genomics applying tool compounds to target validation

Each approach has strengths and limitations; confidence in target validation increases significantly when multiple approaches converge on the same conclusion [5].

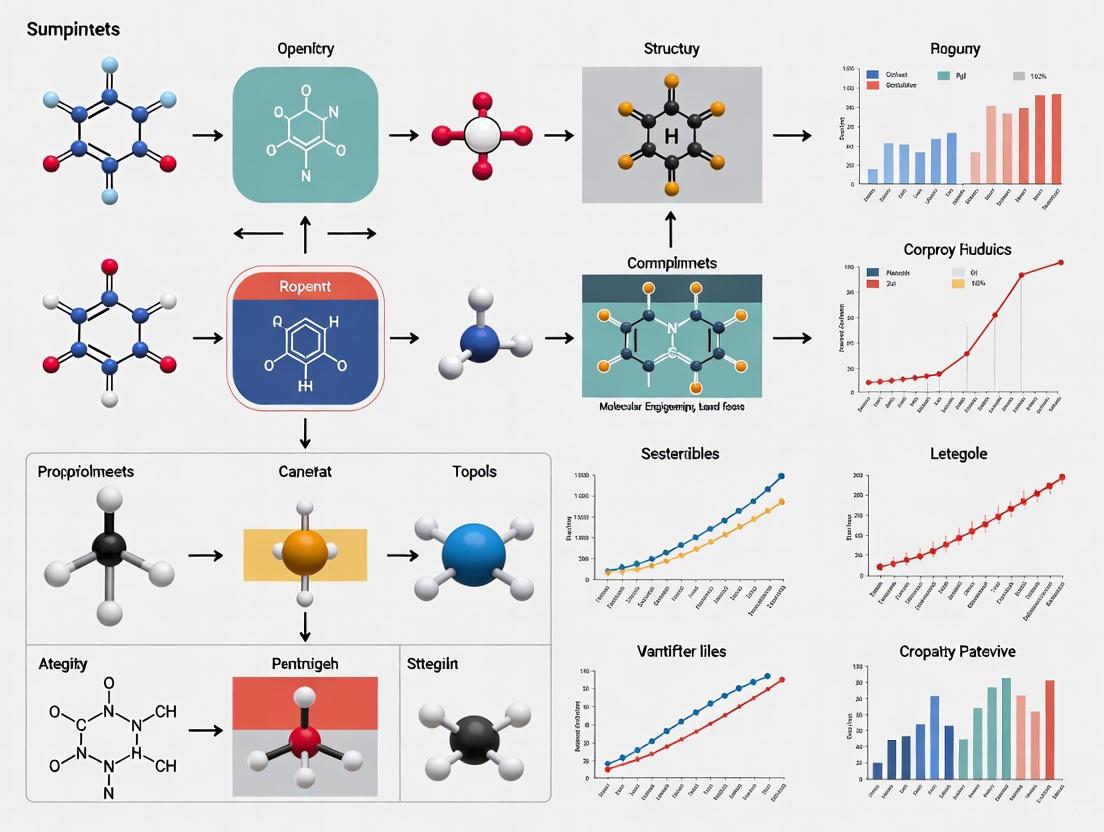

Diagram 1: Target identification and validation workflow for SAR studies.

Assay Development for SAR Profiling

Comprehensive SAR requires a screening cascade of assays that evaluate multiple properties [5]:

- Primary potency assays (enzyme inhibition, receptor binding)

- Selectivity panels against related targets

- Cellular activity assays in relevant cell lines

- ADME profiling (absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion)

- Early toxicity assessment

- Physicochemical property determination

Each assay in the cascade must be validated for reproducibility and relevance to the therapeutic context. The most valuable SAR comes from analyzing patterns across multiple assay endpoints simultaneously.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents and Materials

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for SAR Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function in SAR Studies | Key Considerations |

|---|---|---|

| Chemical Building Blocks | Synthesis of structural analogs for SAR exploration | Diversity, reactivity, compatibility with synthesis routes |

| Assay Kits | Standardized biological activity testing | Reproducibility, sensitivity, relevance to therapeutic mechanism |

| Cell Lines | Cellular-level activity assessment | Physiological relevance, reproducibility, genetic stability |

| Animal Models | In vivo efficacy and PK/PD relationships | Translational relevance, ethical considerations, cost |

| Analytical Standards | Compound characterization and quantification | Purity, stability, appropriate reference materials |

| Chromatography Materials | Compound purification and analysis | Resolution, reproducibility, compatibility with compound properties |

| Target Proteins/Enzymes | Direct binding and functional assays | Activity, purity, structural integrity |

| Antibodies | Target detection and validation in complex systems | Specificity, affinity, lot-to-lot consistency [5] |

Data Analysis and Interpretation in SAR

SAR Landscape Visualization

The landscape paradigm of SAR data provides an alternative view of structure-activity relationships, visualizing chemical structure and bioactivity simultaneously in a 3D view with structure represented in the X-Y plane and activity along the Z-axis [4]. This approach allows SAR datasets to be viewed as landscapes of varying "topography," where:

- Smooth regions correspond to molecules that are similar in structure and activity

- Jagged regions represent areas where small structural changes cause large activity changes

- Activity cliffs occur when minimal structural modifications result in dramatic potency changes

This visualization technique helps identify regions of chemical space with desirable SAR characteristics and guides decisions about which structural modifications to explore next.

Interpretation of QSAR Models

For SAR exploration, the interpretability of QSAR models is often more important than pure predictive ability [4]. Models should be understandable in terms of both the descriptors used and the underlying model itself [4]. Linear regression and random forests often serve well for interpretive purposes, while more complex "black box" models may require additional interpretation tools [4].

Modern approaches to model interpretation include visualization techniques like the "glowing molecule" representation, where color coding corresponds to the influence of specific substructural features on the predicted property [4]. This allows users to directly understand how structural modifications at specific positions will affect the property being optimized.

Diagram 2: Integrated computational workflow for interpretable SAR analysis.

Inverse QSAR Approaches

While traditional QSAR predicts activity from structure, inverse QSAR aims to identify structures that match a given activity profile [4]. Most formulations derive sets of descriptor values rather than structures directly, with the challenge being identification of valid structures from these descriptor values [4]. Recent approaches use novel descriptors coupled with kernel methods to allow explicit mapping between points in high-dimensional kernel space back to the original descriptor space and then to candidate molecules [4].

Applications in Drug Discovery and Development

Lead Optimization Strategies

SAR principles are most extensively applied during the lead optimization phase, where initial hit compounds are transformed into development candidates [5]. This process typically involves:

- Potency optimization through targeted structural modifications

- Selectivity enhancement to minimize off-target effects

- ADME property improvement to achieve desirable pharmacokinetics

- Toxicity mitigation by eliminating or modifying problematic structural elements

- Physicochemical property optimization for developability

The multi-parameter nature of lead optimization requires careful balancing of competing objectives, making comprehensive SAR across multiple endpoints essential for success.

Case Study: G Protein-Coupled Receptors (GPCRs)

GPCRs represent one of the most successful target classes for small molecule drug discovery, due in large part to well-established SAR principles [5]. SAR development for GPCR targets typically follows these patterns:

- Core scaffold identification from screening or literature

- Substituent exploration at key positions affecting potency

- Bioisosteric replacement to improve properties while maintaining activity

- Conformational constraint to optimize receptor fit and selectivity

- Property-based design to fine-tune ADME characteristics

The wealth of historical SAR data for GPCR targets makes them particularly amenable to computational approaches and predictive modeling.

Emerging Applications in Chemical Biology

Beyond traditional drug discovery, SAR principles are increasingly applied in chemical biology for:

- Chemical probe development for target validation

- Photopharmaceuticals with light-dependent activity

- PROTACs (Proteolysis Targeting Chimeras) for targeted protein degradation

- Covalent inhibitor design with controlled reactivity

- Bifunctional molecules with complex mechanism of action

These applications often require extension of classical SAR concepts to include additional parameters such as light sensitivity, linker optimization, or warhead reactivity.

Integration of Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning

The field of SAR analysis is being transformed by artificial intelligence and machine learning approaches [6] [7]. ML excels at processing high-dimensional data and identifying complex nonlinear relationships between dye structure, synthesis processes, and properties [7]. In drug discovery, ML enables:

- Integration of fragmented experimental data to uncover hidden patterns

- Rapid property prediction reducing development timelines

- Data-driven molecular design highlighting structures likely to meet target performance

- Optimization of synthesis parameters to improve yield and reduce waste [7]

The emerging integration of explainable AI (XAI) with traditional SAR analysis addresses the critical need for interpretability in complex models, helping to build trust and facilitate collaboration between computational and experimental scientists [6].

High-Throughput and Automation Technologies

Advances in automation and miniaturization continue to expand the scope and scale of SAR exploration. Key developments include:

- Ultra-high-throughput screening capabilities

- Automated synthesis and purification platforms

- Microfluidic assay systems for reduced reagent consumption

- Automated data analysis and visualization tools

- Integrated data management systems for SAR data

These technologies enable more comprehensive exploration of chemical space and more efficient optimization cycles.

Structure-Activity Relationship analysis remains a cornerstone of drug discovery and development, providing the fundamental principles that guide rational compound optimization. While the core concept—that biological activity follows from chemical structure—has remained unchanged since its first articulation in the 19th century, the methodologies for SAR exploration have evolved dramatically [1] [2]. Modern SAR integrates computational prediction, high-throughput experimentation, and sophisticated data analysis to navigate chemical space efficiently [4] [6]. The continued development of SAR principles, particularly through integration with artificial intelligence and automation technologies, promises to further accelerate the discovery and optimization of therapeutic agents for human health.

Key Structural Features Governing Bioactivity, Solubility, and Toxicity

The relationship between a molecule's structure and its properties is a fundamental tenet in chemistry, underpinning the design of novel pharmaceuticals and agrochemicals. For researchers and drug development professionals, a deep understanding of how specific structural features govern bioactivity, solubility, and toxicity is crucial for accelerating the discovery process and mitigating safety-related attrition. This guide synthesizes current research and established principles to provide a technical overview of these structure-property relationships, framing them within the broader context of molecular structure and property research. The integration of Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) modeling and modern machine learning techniques now allows for the prediction of these properties with increasing accuracy, bridging the gap between molecular design and functional outcome [9] [10].

Core Structural Features and Their Influence on Molecular Properties

Structural Determinants of Bioactivity

Bioactivity is often a function of a molecule's ability to interact with a specific biological target, such as a protein or enzyme. This interaction is governed by a combination of hydrophobic, electronic, and steric factors.

- Hydrophobicity (log P): The n-octanol/water partition coefficient (log P) is a critical parameter that describes a molecule's hydrophobicity. It profoundly influences a compound's ability to cross lipid membranes and reach its site of action. The relationship between log P and bioactivity is often parabolic; activity typically increases with log P until an optimal point (log P₀), after which it declines due to poor aqueous solubility or an inability to leave the lipid phase [11] [12].

- Electronic Effects: The electron density around key functional groups in a molecule dictates its reactivity and binding affinity. Electron-withdrawing or electron-donating substituents can significantly modulate bioactivity by influencing interactions like hydrogen bonding or by making a molecule more electrophilic (electron-deficient) and thus more reactive with nucleophilic biological sites [11] [9].

- Steric and Stereochemical Factors: The three-dimensional shape and size of a molecule are critical for a "lock-and-key" fit with the biological target. Stereoisomers, which contain identical atoms and functional groups but differ in their spatial arrangement, can exhibit vastly different biological activities. Similarly, bulky substituents near an active site can enhance or completely disrupt binding [11].

Structural Features Governing Solubility and Permeability

Solubility and permeability are key determinants of a compound's bioavailability. The most influential factor is a molecule's hydrophobicity, quantified by log P. Highly hydrophobic compounds (high log P) tend to have poor aqueous solubility, which can limit their absorption in the gastrointestinal tract. Conversely, highly hydrophilic compounds (low log P) may struggle to cross lipid membranes [11]. Introducing polar functional groups, such as hydroxyl (-OH) or carboxylic acid (-COOH), can improve aqueous solubility. However, as demonstrated with simple alcohols, the effect of a functional group is context-dependent; while mid-chain alcohols (1-10 carbons) are toxic and somewhat soluble, the -OH group in sugars or long-chain alcohols (>14 carbons) does not confer the same solubility or toxicity profile [11].

Structural Features Influencing Toxicity

Toxicity can arise from a molecule's intrinsic reactivity or its specific interaction with off-target biological pathways.

- Reactive Functional Groups: Some functional groups are inherently electrophilic and can form covalent bonds with nucleophilic sites in proteins or DNA, leading to cell damage or mutagenesis. Identifying these structural alerts is a key step in early toxicity screening.

- Hydrophobicity and Toxicity: For many non-specific toxicities, such as narcosis, hydrophobicity is a primary driver. As log P increases, the tendency for a chemical to accumulate in biological membranes and disrupt their function also increases [12].

- Electronic Descriptors and Toxicity: The electrophilicity index (ω), a parameter derived from Conceptual Density Functional Theory (CDFT), has emerged as a powerful descriptor for predicting toxicity. It quantifies a molecule's electrophilic power and has been successfully correlated with toxicity for various compound classes, often providing a more direct link to reactivity-mediated toxicity than log P alone [9].

- Mechanism-Based Toxicity: The Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) framework links a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE), such as the binding of a compound to a specific protein target, to an adverse outcome. QSAR models can predict a compound's activity against MIE-related protein targets (e.g., receptors, enzymes, transporters), providing a mechanism-based assessment of its potential toxicity [10].

Table 1: Key Molecular Descriptors and Their Relationships with Bioactivity, Solubility, and Toxicity

| Molecular Descriptor | Description | Relationship with Bioactivity | Relationship with Solubility | Relationship with Toxicity |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Hydrophobicity (log P) | n-octanol/water partition coefficient | Parabolic relationship; optimal value (log P₀) exists [11] | High log P generally correlates with low aqueous solubility [11] | Often increases with log P for non-specific toxicity (e.g., narcosis) [12] |

| Electrophilicity Index (ω) | Measures a molecule's electrophilic power [9] | Can correlate with activity for mechanisms involving electrophile-nucleophile interactions [9] | Not a direct driver | Strong predictor for reactivity-mediated toxicity (e.g., mutagenicity) [9] |

| Molar Refractivity | Measure of molecular volume and polarizability | Can indicate steric influences on binding | Can influence crystal packing and solubility | Identified as a factor in organophosphate toxicity [12] |

| Molecular Mass | Molecular weight of the compound | Can influence binding kinetics and diffusion | Larger molecules tend to have lower solubility | Can be a factor in toxicity models [12] |

Experimental and Computational Methodologies

Quantitative Structure-Activity/Property Relationship (QSAR/QSPR) Modeling

QSAR modeling is a computational technique that establishes a mathematical relationship between a molecule's structural descriptors and its biological activity or physicochemical property.

- Data Curation and Preparation: The process begins with the collection of high-quality, standardized experimental data. For toxicity, this may be values like pLC50 (the negative logarithm of the concentration lethal to 50% of a test population) [9]. For bioactivity, data such as IC₅₀ or Kᵢ from databases like ChEMBL are used and often binarized (active/inactive) based on a threshold (e.g., 10,000 nM) [10].

- Descriptor Calculation and Selection: A wide array of molecular descriptors is computed, including:

- Theoretical Descriptors: Quantum chemical descriptors like ionization potential (I) and electron affinity (A) are calculated using computational chemistry methods. These are used to derive electrophilicity (ω), chemical potential (μ), and hardness (η) using finite difference approximations or Koopmans' theorem [9].

- Empirical Descriptors: Hydrophobicity (log P) is a key empirical or calculated descriptor [12].

- Other Descriptors: Topological, geometric, and polar descriptors are also considered [12]. Statistical methods are then used to select the most relevant and non-redundant descriptors for the model.

- Model Development and Validation: Statistical or machine learning algorithms, such as Multiple Linear Regression (MLR) [9] or more advanced methods, are used to build the model. The model must be rigorously validated using internal (e.g., cross-validation) and external test sets to ensure its predictive reliability and robustness [12].

Integrating the Adverse Outcome Pathway (AOP) Framework

The AOP framework provides a systematic structure for understanding toxicity mechanisms, linking a Molecular Initiating Event (MIE) to an Adverse Outcome (AO) through a series of Key Events (KEs). QSAR models can be developed to predict the initial MIE, such as a compound's binding to or inhibition of a specific protein target associated with organ-specific toxicity [10]. For example:

- Liver Steatosis: MIEs include binding to receptors like AHR, LXR, PXR, PPARα, and PPARγ [10].

- Cholestasis: MIEs involve inhibition of transporters like BSEP, MRP2, MRP3, MRP4, and NTCP [10].

- Kidney Failure: MIEs include interaction with transporters (OAT1) and enzymes (COX1, ACE) [10].

High-quality bioactivity data from sources like the ChEMBL database for these protein targets are used to build robust QSAR models, enabling the prioritization of chemicals based on their potential to trigger MIEs [10].

Machine Learning and Multi-Task Learning in Low-Data Regimes

Data scarcity is a major challenge in molecular property prediction. Machine learning, particularly Multi-Task Learning (MTL), can leverage correlations between related properties to improve predictive accuracy when data for a single property is limited. However, MTL can suffer from negative transfer, where updates from one task degrade performance on another, especially under severe task imbalance [13].

Advanced training schemes like Adaptive Checkpointing with Specialization (ACS) have been developed to mitigate this. ACS uses a shared graph neural network (GNN) backbone with task-specific heads. It monitors validation loss for each task and checkpoints the best backbone-head pair for a task when its loss hits a new minimum, protecting individual tasks from detrimental parameter updates while preserving the benefits of shared learning [13]. This approach has enabled accurate property prediction with as few as 29 labeled samples [13].

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item/Tool Name | Function/Description | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|

| ChEMBL Database | A manually curated database of bioactive molecules with drug-like properties [10]. | Primary source of high-quality bioactivity data (e.g., pChEMBL values) for training QSAR models on MIE-related targets [10]. |

| Dispersion-Inclusive DFT | A computational method for accurately calculating the energy and geometry of molecular systems, accounting for dispersion forces [14]. | Used to generate large, reliable datasets of molecular crystal structures and properties for training machine learning potentials (e.g., OMC25 dataset) [14]. |

| Gaussian 16 Program | A software package for electronic structure modeling [9]. | Used for geometry optimization, frequency calculations, and computing quantum chemical descriptors (e.g., HOMO/LUMO energies for ω, μ, η) [9]. |

| Graph Neural Network (GNN) | A type of neural network that operates directly on the graph structure of a molecule [13]. | Serves as the backbone architecture in modern property predictors (e.g., ACS) for learning powerful molecular representations [13]. |

| AOP-Wiki | A knowledgebase platform for collaborative development of Adverse Outcome Pathways [10]. | Used to identify relevant Molecular Initiating Events (MIEs) and their associated protein targets for QSAR model development [10]. |

The integration of traditional physicochemical principles, such as hydrophobicity and electronic effects, with modern computational frameworks like QSAR, AOP, and advanced machine learning, provides a powerful, multi-faceted approach to understanding and predicting molecular properties. The move towards mechanism-based models, particularly those integrated with the AOP framework, offers a more nuanced and predictive understanding of toxicity, extending beyond simple correlation to biological causation. As computational power and algorithms continue to advance, the ability to accurately design molecules with optimal bioactivity, solubility, and safety profiles from the outset will become increasingly routine, fundamentally transforming the landscape of drug and chemical development.

In the pursuit of rational drug and material design, understanding the relationship between molecular structure and observable properties represents a fundamental challenge. For generations, chemists have relied on functional groups—specific groupings of atoms with characteristic chemical behavior—as cornerstone concepts for predicting reactivity, solubility, and biological activity. These recognizable substructures provide a chemical lexicon that transcends individual molecular entities, enabling scientists to infer properties based on analogous structures. Similarly, stereochemistry introduces a three-dimensional perspective that critically influences molecular interactions, particularly in biological systems where chiral recognition dominates. Within contemporary molecular research, the advent of sophisticated machine learning and deep learning models has revolutionized property prediction, yet this progress has often occurred at the expense of chemical interpretability. Modern computational approaches frequently utilize abstract structural and topological descriptors that obscure the very chemical principles—functional groups and stereochemistry—that practicing chemists employ in their reasoning [15]. This whitepaper examines how recent computational frameworks are reintegrating these fundamental chemical concepts to create models that achieve state-of-the-art predictive performance while remaining intrinsically interpretable, thereby bridging the gap between data-driven inference and chemical intuition.

Functional Groups as Interpretable Descriptors in Machine Learning

The Interpretability Challenge in Molecular ML

Deep learning models have demonstrated remarkable performance in molecular property prediction, yet their widespread adoption in chemical discovery has been hampered by their "black box" nature. While graph neural networks (GNNs) and transformer-based architectures can capture complex structure-property relationships, the resulting representations often lack direct chemical meaning, making it difficult for researchers to extract actionable insights or develop chemical intuition from model predictions [16]. This interpretability deficit presents a significant barrier for practical applications, particularly in drug discovery where understanding structure-activity relationships is crucial for lead optimization. The challenge extends beyond mere prediction accuracy; chemists require models that not only predict but also explain, linking model outputs to established chemical principles and suggesting plausible structural modifications [17].

The Functional Group Representation (FGR) Framework

A groundbreaking approach addressing this interpretability challenge is the Functional Group Representation (FGR) framework, which proposes that "functional groups are all you need" for chemically interpretable molecular property prediction [16]. This methodology revives the traditional chemical concept of functional groups as fundamental descriptors for machine learning applications. The FGR framework operates through a systematic two-stage process:

Vocabulary Generation: The framework constructs a comprehensive vocabulary of chemical substructures using two complementary approaches: (1) Expert-curated functional groups (FG) sourced from established chemical knowledge bases like ToxAlerts, and (2) Mined functional groups (MFG) discovered from large molecular databases such as PubChem using sequential pattern mining algorithms applied to SMILES representations [16].

Latent Space Encoding: Molecules are encoded based on their constituent functional groups and processed through autoencoder architectures to generate lower-dimensional latent representations. These functional group-based embeddings can be further enriched with traditional molecular descriptors before being deployed for property prediction tasks [16].

This approach aligns machine learning representations with established chemical principles, ensuring that model predictions can be directly traced back to specific functional groups—a significant advancement for interpretability in molecular ML [15].

Experimental Protocol for FGR Implementation

Materials and Computational Methods:

- Data Sources: PubChem database (approximately 100 million compounds) for mined functional group discovery; ToxAlerts database for expert-curated functional groups [16].

- Pattern Mining Algorithm: Sequential pattern mining applied to SMILES strings to identify frequently occurring substructures with minimum support threshold of 0.1% of the database [16].

- Autoencoder Architecture: Multilayer perceptron with bottleneck structure for latent space generation; dimensions optimized for specific prediction tasks.

- Training Protocol: Two-phase training with initial unsupervised pre-training on unlabeled molecular structures followed by supervised fine-tuning on target properties.

- Validation: Benchmarking against 33 diverse datasets spanning physical chemistry, biophysics, quantum mechanics, and pharmacokinetics [16].

Beyond Atoms: Substructure-Level Molecular Representations

The Group Graph Approach

Complementing the FGR framework, the "group graph" representation offers an alternative substructure-based paradigm for molecular machine learning. This approach constructs molecular graphs where nodes represent chemically meaningful substructures rather than individual atoms, and edges represent the connections between these substructures [18]. The group graph methodology employs a systematic fragmentation process:

- Active Group Identification: Traditional functional groups are decomposed into charged atoms, halogens, and small groups containing double or triple bonds. Aromatic rings are identified as distinct substructures due to their significant influence on molecular properties [18].

- Substructure Extraction: Remaining non-active atoms are grouped into "fatty carbon groups" based on connectivity patterns.

- Graph Construction: The resulting substructures serve as nodes, with edges representing bonds between them, creating a simplified yet chemically informative molecular representation [18].

This representation demonstrates that substructure-level graphs can retain essential molecular structural information with reduced complexity, leading to both computational efficiency and enhanced interpretability.

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Representations

Table 1: Performance Characteristics of Different Molecular Representations

| Representation Type | Interpretability | Performance on Benchmark Tasks | Handling of 3D Geometry | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Functional Group Representation (FGR) [16] | High (direct chemical meaning) | State-of-the-art on ADMET, biophysics, quantum chemistry | Limited performance | Chemical interpretability; Integration with established principles |

| Group Graph [18] | High (substructure-level features) | Superior to atom graphs in property prediction | Not addressed | Minimal information loss; Detection of activity cliffs |

| Atom Graph (GNN) [18] | Medium (requires post-hoc interpretation) | Strong performance across tasks | Moderate with geometric learning | Comprehensive structural information |

| SMILES/Sequence [16] | Low to Medium (token-based) | Variable performance | Poor | Simple implementation; Large pre-trained models available |

| Molecular Fingerprints [16] | Medium (substructure presence) | Good performance on similar tasks | None | Standardized; Fast computation |

Stereochemistry and Three-Dimensional Considerations

The Limitations of Current Substructure Approaches

While functional group-based representations mark significant progress in interpretable molecular machine learning, they face inherent limitations in capturing three-dimensional structural information, particularly stereochemistry. The current FGR framework primarily operates on 2D structural representations, potentially overlooking critical stereochemical features that profoundly influence molecular properties and biological activity [15]. This represents a significant gap, as stereochemistry dictates pharmacophore orientation, binding affinity, and metabolic fate in pharmaceutical applications. The group graph approach similarly focuses on topological connectivity without explicit encoding of spatial arrangements [18]. This limitation becomes particularly consequential for drug discovery applications where enantiomeric forms can exhibit dramatically different pharmacological profiles, emphasizing the need for future frameworks that integrate stereochemical information with functional group-based representations.

Experimental Visualization and Workflows

Functional Group Representation Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the comprehensive workflow for the Functional Group Representation framework, from data processing through to property prediction:

Group Graph Construction Methodology

The group graph representation involves a systematic transformation from traditional molecular structures to substructure-based graphs, as detailed in the following workflow:

Table 2: Key Computational Tools and Resources for Functional Group Analysis

| Resource/Tool | Type | Primary Function | Application in Research |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem Database [16] | Chemical Database | Provides molecular structures and properties | Source for mined functional group discovery; Benchmark datasets |

| ToxAlerts Database [16] | Specialized Database | Expert-curated toxicological functional groups | Source of chemically validated substructures for FGR framework |

| RDKit [18] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Molecular pattern matching and fragmentation | Identification of aromatic rings and functional group decomposition |

| ABIET Tool [19] | Transformer-Based Analysis | Attention-based importance estimation for SMILES tokens | Identification of critical functional groups in drug-target interactions |

| BRICS/MacFrag [18] | Fragmentation Algorithms | Molecular decomposition into substructures | Comparative approach for substructure identification in group graphs |

The resurgence of functional groups as fundamental descriptors in molecular machine learning represents a paradigm shift toward chemically intuitive artificial intelligence. Approaches like the Functional Group Representation framework and group graphs demonstrate that leveraging domain knowledge through substructure-based representations can achieve state-of-the-art predictive performance while maintaining interpretability—a crucial combination for accelerating scientific discovery. These methodologies empower researchers to trace model predictions directly to recognizable chemical features, bridging the gap between data-driven inference and chemical reasoning. Nevertheless, the ongoing challenge of incorporating three-dimensional structural information, particularly stereochemistry, highlights an important direction for future research. As these frameworks evolve to encompass the full complexity of molecular structure—from functional groups to spatial arrangements—they promise to further transform molecular design across pharmaceuticals, materials science, and chemical discovery, creating tools that augment rather than replace chemical intuition.

The U.S. Food and Drug Administration's (FDA) Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER) approved 50 novel drugs in 2024, comprising a diverse array of molecular modalities and therapeutic mechanisms [20] [21]. This cohort provides a rich dataset for analyzing modern structure-property relationship (SPR) principles applied in successful drug development. While the total number represents a slight decrease from 2023's 55 approvals, it exceeds the 10-year rolling average of 46.5 novel approvals per year, indicating sustained productivity in pharmaceutical innovation [21] [22]. The 2024 approval class was notable for its significant proportion of first-in-class (FIC) therapeutics, with 22 (44%) of the approved drugs featuring novel mechanisms of action unrelated to previously approved medicines [23] [24]. This high proportion of pioneering therapies offers exceptional opportunities to extract structure-property insights from unprecedented target-compound interactions.

Molecular diversity characterized the 2024 approvals, with small molecules constituting approximately 60% (30 drugs) of the cohort, while biologics accounted for 32% (16 drugs) [22]. The remaining approvals included oligonucleotides, peptides, and other specialized modalities. From a therapeutic area perspective, oncology maintained dominance with 14 new drug approvals (28%), followed by rare diseases (20%), cardiovascular and metabolic conditions, infectious diseases, and autoimmune disorders [23]. A substantial 56% of approvals received priority review, 52% carried orphan drug designation, and 36% qualified as breakthrough therapies, indicating that these drugs addressed significant unmet medical needs and demonstrated substantial improvement over existing therapies [22]. This review extracts critical structure-property lessons from these successful candidates, providing a framework for rational drug design informed by the most contemporary successful examples.

Quantitative Analysis of 2024 Drug Approvals

Table 1: Molecular and Regulatory Characteristics of 2024 FDA Drug Approvals

| Characteristic | Number | Percentage | Notable Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Total Novel Drugs | 50 | 100% | |

| Small Molecules | 30 | 60% | Rezdiffra, Cobenfy, Voranigo |

| Biologics | 16 | 32% | Kisunla, Imdelltra, Piasky |

| TIDES (Oligos/Peptides) | 4 | 8% | Rytelo, Tryngolza, Yorvipath |

| First-in-Class Drugs | 22 | 44% | Rezdiffra, Voydeya, Voranigo |

| Orphan Drug Designations | 26 | 52% | Xolremdi, Ojemda, Miplyffa |

| Priority Reviews | 28 | 56% | Kisunla, Winrevair, Rezdiffra |

| Oncology Approvals | 14 | 28% | Itovebi, Imdelltra, Ensacove |

Table 2: Structural and Property Analysis of Representative 2024 Small Molecule Approvals

| Drug (Brand Name) | Target/Mechanism | Key Structural Features | PK/PD Properties | Design Innovation |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lazcluze (lazertinib) | EGFR kinase inhibitor | Tetrahydroimidazo[4,5-c]quinoline core | t½: 3.7 days; CYP3A4 metabolism | CNS-penetrant; mutant-selective |

| Rezdiffra (resmetirom) | THR-β agonist | Phenolic biaryl ether; liver-targeted | Extensive tissue distribution | Tissue-selective nuclear receptor modulation |

| Cobenfy (xanomeline + trospium) | M1/M4 mAChR agonist + peripheral antagonist | Quaternary ammonium (trospium) | Xanomeline t½: 5h; Trospium t½: 6h | Central/peripheral activity segregation |

| Voranigo (vorasidenib) | IDH1/2 inhibitor | Pyrazolopyrimidine scaffold | High brain penetration | Dual IDH1/2 inhibition; brain-targeted |

| Alyftrek (vanzacaftor/tezacaftor/deutivacaftor) | CFTR correctors/potentiator | Deuterated modifications | Vanzacaftor t½: 92.8h | Deuteration for improved PK |

| Revuforj (revumenib) | Menin-KMT2A interaction inhibitor | Sulfonamide-based scaffold | Once or twice daily dosing | Protein-protein interaction inhibition |

The 2024 approvals demonstrated several noteworthy trends in molecular design strategy. Small molecule drugs increasingly incorporated structural motifs to address specific property challenges: fluorinated compounds and N-aromatic heterocycles appeared in 66% of small molecules, reflecting continued emphasis on metabolic stability and target engagement [22]. Additionally, strategic deployment of deuterium incorporation in drugs like deutivacaftor (Alyftrek) exemplified sophisticated approaches to optimizing pharmacokinetic profiles without altering primary pharmacology [22] [25]. The high proportion of first-in-class drugs (44%) indicates successful exploration of novel chemical space, with particular innovation in targeted protein degradation, allosteric modulation, and protein-protein interaction inhibition [26] [24].

Analysis of the physicochemical properties reveals that 2024's small molecule approvals generally conform to modern druglikeness principles, with some strategic exceptions for challenging targets. CNS-active agents like lazertinib and vorasidenib demonstrated optimized properties for blood-brain barrier penetration, including moderate molecular weights and careful balance of lipophilicity and polar surface area [22] [25]. Conversely, peripherally-restricted agents like trospium chloride in Cobenfy incorporated permanent charges to limit central exposure, enabling targeted pharmacological effects while minimizing off-target adverse events [22]. These strategic property designs highlight the sophisticated application of structure-property relationship principles to achieve precise tissue distribution and elimination profiles tailored to specific therapeutic objectives.

Structural Insights and Property Relationships from Key Approvals

Case Study 1: Lazcluze (Lazertinib) - Optimizing CNS Exposure

Lazertinib, approved for EGFR-mutant non-small cell lung cancer, exemplifies structure-based design for central nervous system exposure, a critical requirement for addressing brain metastases common in this malignancy [22] [25]. The molecular structure incorporates a tetrahydroimidazo[4,5-c]quinoline core that balances hydrophobicity with hydrogen bonding potential, enabling effective blood-brain barrier penetration while maintaining solubility. Key structural modifications from earlier generations of EGFR inhibitors reduced efflux transporter susceptibility, particularly P-glycoprotein recognition, which historically limited CNS accumulation [22].

The structure-property relationship of lazertinib manifests in its favorable pharmacokinetic profile, including a large volume of distribution (Vd: 2680 L) indicating extensive tissue penetration, and an extended half-life (3.7 days) supporting once-daily dosing [22]. Metabolism occurs primarily via glutathione conjugation and CYP3A4, with minimal renal excretion of unchanged drug (≤0.2%), reducing the potential for drug-drug interactions in renally impaired patients [22]. The structural design also confers selective inhibition of activating EGFR mutations while sparing wild-type EGFR, mitigating dose-limiting toxicities like skin rash and diarrhea that plagued earlier generation inhibitors [25].

Diagram 1: Lazertinib PK/PD Pathway

Case Study 2: Cobenfy (Xanomeline/Trospium) - Dual-Component Engineering

Cobenfy represents a innovative approach to receptor selectivity challenges through a combination of two active components with complementary distribution profiles [22] [25]. Xanomeline, a central M1/M4 muscarinic agonist, features structural elements optimized for crossing the blood-brain barrier, including moderate molecular weight and balanced lipophilicity. In contrast, trospium chloride incorporates a permanent positive charge that restricts CNS penetration, functioning as a peripherally-restricted antagonist that mitigates the peripheral cholinergic side effects that limited earlier development of xanomeline as a monotherapy [22].

The structure-property relationships of this combination manifest in their divergent pharmacokinetic profiles: xanomeline reaches peak concentrations rapidly (Tmax: 2 hours) with a relatively short half-life (5 hours), while trospium chloride shows similar Tmax (1 hour) and half-life (6 hours) but dramatically reduced systemic exposure when administered with food (85-90% reduction in AUC) [22]. This property enables strategic dosing to optimize the therapeutic index. The structural design of trospium as a quaternary ammonium compound ensures primarily renal elimination (85-90% unchanged), minimizing metabolic drug-drug interactions and providing a predictable safety profile [22].

Case Study 3: Rezdiffra (Resmetirom) - Tissue-Selective Nuclear Receptor Agonism

Resmetirom, the first-approved therapy for non-alcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH), demonstrates sophisticated tissue-selective receptor targeting through strategic molecular design [25] [24]. As a thyroid hormone receptor-β (THR-β) agonist, resmetirom incorporates structural modifications that confer selectivity for the hepatic β-isoform over the cardiac α-isoform of thyroid hormone receptors, mitigating cardiovascular concerns that hampered earlier non-selective thyroid receptor agonists [24]. The phenolic biaryl ether structure enables optimal receptor engagement while directing liver-specific distribution through expression patterns of hepatic transporters.

The structure-property relationship of resmetirom results in favorable liver-targeted exposure with rapid achievement of steady-state (3-6 days) and dose-proportional pharmacokinetics across the therapeutic range [22]. The molecular design facilitates extensive hepatic extraction, ensuring high local concentrations at the site of action while limiting extrahepatic exposure. This tissue-selective distribution underlines the drug's efficacy in reducing liver fat accumulation and inflammation while demonstrating an acceptable safety profile in clinical trials [25] [24].

Diagram 2: Resmetirom Mechanism of Action

Experimental Methodologies for Structure-Property Optimization

ADME Profiling Protocols

Comprehensive absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) profiling formed the foundation for structure-property optimization across the 2024 drug approvals. Standardized experimental protocols enabled systematic comparison of candidate compounds and informed structural refinement [22]. For permeability assessment, the parallel artificial membrane permeability assay (PAMPA) provided high-throughput screening of passive transport, while Caco-2 cell monolayers evaluated active transport and efflux mechanisms, particularly critical for CNS-targeted agents like lazertinib [22].

Metabolic stability studies employed human liver microsomes and hepatocytes to quantify intrinsic clearance and identify primary metabolic soft spots. For lazertinib, these studies revealed glutathione conjugation as a significant pathway, informing clinical drug-drug interaction risk assessment [22]. Distribution studies included plasma protein binding measurements via equilibrium dialysis and tissue distribution assessments in preclinical models, with particular emphasis on brain-to-plasma ratios for CNS-targeted therapeutics. These protocols enabled quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models that correlated specific structural features with optimal ADME properties, guiding lead optimization campaigns [22] [25].

Protein-Target Interaction Mapping

Structural biology approaches provided atomic-level insights into target engagement mechanisms that informed property-based design. X-ray crystallography of drug-target complexes revealed critical interaction patterns, such as the menin-binding mode of revumenib (Revuforj), which guided optimization of binding affinity while maintaining favorable physicochemical properties [25]. For covalent inhibitors like itovebi (inavolisib), mass spectrometry-based approaches characterized modification kinetics and selectivity, enabling tuning of reactivity to achieve optimal target coverage while minimizing off-target effects [25].

Biophysical interaction analysis using surface plasmon resonance and thermal shift assays quantified binding kinetics and thermodynamics, providing parameters for structure-property correlations. For the CFTR modulators in Alyftrek, these approaches helped optimize corrector-potentiator combinations with complementary binding sites and kinetics, enabling synergistic rescue of mutant CFTR function [22] [23]. The integration of these structural insights with property optimization represented a recurring theme in the 2024 approvals, demonstrating the power of structure-based design in modern drug development.

Table 3: Essential Research Toolkit for Structure-Property Analysis

| Technique/Category | Specific Methods | Application in Drug Discovery | 2024 Approval Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Physicochemical Profiling | PAMPA, Caco-2, solubility assays, pKa determination | Permeability prediction, formulation assessment | Cobenfy components (divergent food effects) |

| Metabolic Stability | Liver microsomes, hepatocytes, reaction phenotyping | Clearance prediction, DDI risk assessment | Lazcluze (CYP3A4/GSH metabolism) |

| Drug Transport | Transporter assays (P-gp, BCRP, OATP) | Tissue distribution optimization | Alyftrek components (transporter substrates) |

| Protein Binding | Equilibrium dialysis, ultrafiltration | Free fraction determination, DDI potential | Rezdiffra (extensive tissue distribution) |

| Structural Biology | X-ray crystallography, Cryo-EM | Target engagement optimization | Revuforj (menin interaction) |

| Biophysical Analysis | SPR, ITC, thermal shift | Binding kinetics, mechanism elucidation | Voranigo (IDH1/2 inhibition) |

Pathway Visualization and Mechanistic Relationships

CFTR Modulation Strategy in Alyftrek

The triple combination vanzacaftor/tezacaftor/deutivacaftor (Alyftrek) demonstrates sophisticated structure-based rescue of protein trafficking and function [22] [23]. Each component addresses distinct structural defects in mutant CFTR: vanzacaftor and tezacaftor function as correctors that improve cellular processing and membrane localization, while deutivacaftor acts as a potentiator that enhances channel gating at the cell surface. The deuterated modification in deutivacaftor strategically improves metabolic stability without altering target engagement, exemplifying property-focused structural refinement [22].

The pharmacokinetic optimization of this combination required careful balancing of disposition characteristics across the three components, with vanzacaftor exhibiting an extended half-life (92.8 hours) compared to tezacaftor (22.5 hours) and deutivacaftor (19.2 hours) [22]. All three components are metabolized primarily by CYP3A4, creating a predictable drug-drug interaction profile that can be managed through dose adjustment. The structural designs also minimized inhibition of key transporters except at therapeutic concentrations, reducing the potential for interactions with concomitant medications [22]. This comprehensive approach to combination therapy design represents a significant advance in structure-property optimization for multi-target regimens.

Diagram 3: CFTR Modulation by Alyftrek Components

Targeted Protein Degradation and Allosteric Modulation

Several 2024 approvals exemplified advanced mechanisms beyond conventional occupancy-driven pharmacology, requiring specialized structure-property considerations. Itovebi (inavolisib) functions as both a mutant-selective PI3Kα inhibitor and degrader, incorporating structural elements that facilitate target degradation in addition to enzymatic inhibition [25]. This dual mechanism provides more sustained pathway suppression and overcame limitations of earlier PI3K inhibitors. The molecular structure optimized properties for both target binding and recruitment of the ubiquitin-proteasome system, demonstrating the evolving complexity of structure-property relationship optimization for emerging modalities.

Allosteric modulation featured prominently in drugs like Cobenfy, where xanomeline targets muscarinic receptor subtypes via allosteric sites to achieve improved selectivity profiles compared to orthosteric agonists [25]. The structure of xanomeline enabled preferential stabilization of active states of M1 and M4 receptors over other subtypes, reducing side effects mediated by M2 and M3 receptors. This approach required specialized property optimization to maintain appropriate CNS exposure while achieving sufficient receptor residence time for meaningful clinical effects. These advanced mechanisms illustrate how structure-property relationship principles are adapting to support increasingly sophisticated pharmacological approaches.

The 2024 FDA drug approvals provide compelling case studies in modern structure-property relationship implementation, demonstrating strategic molecular design solutions to complex pharmacological challenges. Several key principles emerge: First, successful drugs increasingly feature property-optimized designs tailored to specific therapeutic contexts, such as CNS penetration for neurology and oncology agents or restricted distribution for peripherally-mediated toxicities. Second, sophisticated biomarker strategies and patient selection approaches enabled successful development of drugs with narrow therapeutic windows, particularly in oncology and rare diseases.

Looking forward, the trends observed in the 2024 cohort suggest several future directions for structure-property optimization: Increased utilization of covalent targeting with tuned reactivity profiles; broader application of deuterium and other strategic isotope incorporation for metabolic stabilization; more sophisticated prodrug approaches to overcome administration challenges; and continued advancement in targeted protein degradation with optimized molecular properties for ternary complex formation. Additionally, the growing representation of oligonucleotide and peptide therapeutics suggests increasing importance of property optimization strategies for these modalities beyond traditional small molecules.

The 2024 approvals collectively demonstrate that while target engagement remains fundamental, optimal therapeutic outcomes increasingly depend on sophisticated structure-property relationship implementation throughout the drug discovery process. The continued high proportion of first-in-class drugs indicates that property optimization strategies are successfully keeping pace with novel target exploration, enabling translation of innovative biological insights into clinically impactful medicines. These successes provide a robust foundation and strategic framework for future drug development efforts across therapeutic areas and modality classes.

Beyond Intuition: AI and Multi-Modal Methods for Predicting Molecular Behavior

The accurate computational representation of molecules is a foundational pillar in modern drug discovery and materials science. The evolution of these representations—from simple human-readable strings to sophisticated, data-driven three-dimensional models—reflects a paradigm shift in how researchers relate molecular structure to biological activity and physicochemical properties. Effective molecular representation serves as the critical bridge between a chemical structure and the prediction of its behavior, directly impacting the efficiency and success of lead optimization and virtual screening campaigns [27] [28].

This technical guide traces the journey of molecular representation methods, framing them within the core scientific pursuit of understanding structure-property relationships. We will explore how initial, intuitive formats have been progressively supplanted by AI-driven approaches that capture deeper structural and physical insights, culminating in powerful 3D-conformational and multi-modal models that offer unprecedented predictive accuracy and interpretability.

The Foundations: Traditional Molecular Representations

Traditional molecular representation methods rely on explicit, rule-based feature extraction to translate molecular structures into a computer-readable format [27]. These methods laid the groundwork for decades of computational chemistry and quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) modeling.

String-Based Representations: SMILES and Beyond

The Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) has been a workhorse representation since its introduction in 1988 [27] [28]. SMILES encodes the molecular graph as a linear string using a compact grammar that denotes atoms, bonds, branches, and ring closures. Its key advantage lies in its simplicity and compactness, making it ideal for database storage and search. However, SMILES has several critical limitations: a single molecule can have multiple valid SMILES strings, its complex grammar leads to high rates of invalid string generation in AI models, and it struggles to capture the nuances of molecular stereochemistry and conformation [29].

Innovations like SELFIES (Self-referencing embedded strings) were developed specifically to address the robustness issues of SMILES in AI applications. SELFIES uses a formal grammar-based approach that guarantees 100% syntactic and semantic validity, even when strings are randomly mutated or generated by neural networks [29]. This robustness has made SELFIES particularly valuable in generative molecular design applications.

Molecular Descriptors and Fingerprints

Molecular descriptors are numerical quantities that capture specific physicochemical properties (e.g., molecular weight, logP, topological indices) [27]. Molecular fingerprints, such as the widely used Extended-Connectivity Fingerprints (ECFP), encode substructural information as binary bit strings or numerical vectors [27] [30]. These fixed-length representations are computationally efficient and excel at similarity searching and clustering, forming the basis for many virtual screening workflows [31].

Table 1: Comparison of Traditional Molecular Representation Methods

| Representation | Format | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES | Linear string | Human-readable, compact, widely supported | Multiple valid representations per molecule, complex grammar, invalid generation issues |

| SELFIES | Linear string | 100% robust, guaranteed validity, ideal for generative AI | Less human-readable, relatively newer with smaller ecosystem |

| Molecular Fingerprints (ECFP) | Binary bit string | Computational efficiency, effective for similarity search, fixed length | Predefined features may miss relevant structural nuances, no explicit structural information |

| Molecular Descriptors | Numerical vector | Direct encoding of physicochemical properties, interpretable | Requires expert knowledge for selection, may not capture complex structural patterns |

The AI Revolution: Data-Driven Representation Learning

The advent of deep learning catalyzed a shift from handcrafted features to learned representations. AI-driven methods employ models such as graph neural networks (GNNs), transformers, and autoencoders to learn continuous, high-dimensional feature embeddings directly from large molecular datasets [27] [31]. These approaches move beyond predefined rules to capture both local and global molecular features, often revealing subtle structure-property relationships inaccessible to traditional methods.

Graph-Based Representations

Graph-based representations explicitly model a molecule's structure by representing atoms as nodes and bonds as edges [27] [31]. This intuitive mapping enables powerful neural architectures to operate directly on molecular graphs.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs), particularly Graph Isomorphism Networks (GINs), have become a cornerstone of modern molecular machine learning [18]. Through message-passing mechanisms, GNNs iteratively aggregate information from a node's local neighborhood, building increasingly sophisticated representations of atomic environments and the overall molecular context.

The Group Graph representation represents a recent innovation that operates at the substructure level rather than the atomic level [18]. By representing common functional groups and aromatic rings as single nodes, group graphs provide enhanced interpretability and can identify activity cliffs—significant changes in property resulting from small structural modifications. Notably, GINs trained on group graphs have demonstrated superior performance in predicting molecular properties and drug-drug interactions while offering a 30% reduction in runtime compared to atom-level graphs [18].

Language Model-Based Representations

Inspired by breakthroughs in natural language processing (NLP), researchers have adapted transformer architectures to understand the "language of chemistry" by treating molecular strings (SMILES or SELFIES) as sequences [27]. These models learn contextualized representations of molecular substructures by pre-training on large unlabeled molecular datasets using objectives like masked token prediction.

The FP-BERT model exemplifies this approach, employing a substructure masking pre-training strategy on ECFP fingerprints to derive high-dimensional molecular representations, which are then processed by convolutional neural networks for downstream prediction tasks [27].

Set-Based Representations

Challenging the necessity of explicit bond definitions, Molecular Set Representation Learning (MSR) proposes representing molecules as permutation-invariant multisets of atoms [30]. This approach captures the "fuzzy" nature of molecular bonding, particularly in conjugated systems where electrons are delocalized.

The MSR1 architecture, which uses only sets of atom invariants without any explicit topological information, surprisingly matches or exceeds the performance of established GNNs like GIN and D-MPNN on several benchmark datasets [30]. This suggests that overly rigid graph definitions may sometimes constrain model performance rather than enhance it.

Table 2: Comparison of AI-Driven Molecular Representation Approaches

| Representation | Architecture | Key Innovations | Best-Suited Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Graph Networks | GNNs, GIN, GAT | Message-passing, explicit structure encoding, high performance | Property prediction, activity cliffs, interpretable QSAR |

| Language Models | Transformers | Contextual substructure understanding, transfer learning from large datasets | Molecular generation, pre-training for data-scarce tasks |

| Set Representation | DeepSets, Set Transformers | Bond-free representation, handles undefined bonding | Complex systems (polymers, conjugated systems), high-throughput screening |

| Multimodal Models | Graph-Transformer hybrids, OmniMol | Integration of multiple representation types, handling imperfect annotation | Holistic property prediction, knowledge transfer across tasks |

The Third Dimension: 3D Conformational Representations

The transition from 2D connectivity to 3D geometry marks a pivotal advancement in molecular representation, enabling researchers to directly model stereochemistry, molecular interactions, and conformational dynamics that fundamentally determine biological activity and physicochemical properties [32] [33].

The Critical Role of 3D Structure

A molecule's three-dimensional conformation profoundly influences its biological and physical properties, including charge distribution, protein interactions, and ultimately, its efficacy as a therapeutic agent [33]. The case of ABT-333 and ABT-072—two hepatitis C virus inhibitors differing only by a minor substituent change—illustrates this principle. This seemingly small modification disrupts molecular planarity, leading to significant differences in conformational preferences, crystal polymorphism, and ultimately, aqueous solubility and formulation challenges [32]. Such nuanced structure-property relationships often remain invisible to 2D representation methods.

3D Representation Methodologies

Cartesian coordinates provide the most direct 3D representation but lack rotational and translational invariance, making them poorly suited for machine learning models. Internal coordinates (bond lengths, angles, and dihedrals) offer invariance but can be sensitive to reconstruction errors [33].

The Graph Information-Embedded Relative Coordinate (GIE-RC) system represents a novel approach that combines the advantages of relative coordinate systems with graph-structured information [33]. This method satisfies translational and rotational invariance while demonstrating superior error resistance compared to Cartesian and internal coordinates. When integrated within an autoencoder framework, GIE-RC transforms the complex 3D generation task into a more manageable graph node feature generation problem, enabling accurate reconstruction of both small molecules and large peptide structures [33].

Conformational Generative Models

Traditional conformational sampling methods like molecular dynamics (MD) and Monte Carlo (MC) simulations are computationally expensive and often struggle to overcome high free energy barriers [33]. Deep conformational generative models offer an alternative by compressing high-dimensional conformational distributions into low-dimensional latent spaces, enabling efficient and parallel sampling.

The Boltzmann generator, a normalized flow-based generative model, can accurately model complex protein conformation distributions and estimate free energy differences between states [33]. GeoDiff learns to reverse a diffusion process to recover molecular geometry from noisy distributions [33]. These approaches demonstrate how 3D-aware generative models can accelerate both conformational analysis and molecular design.

Unified Frameworks and Future Frontiers

As the field progresses, molecular representation learning is increasingly embracing unified, multi-modal frameworks that integrate diverse data types and address practical challenges like imperfect annotation.

Multi-Modal and Unified Frameworks

The OmniMol framework addresses the critical challenge of imperfectly annotated data—where each property is labeled for only a subset of molecules—through a hypergraph-based approach that explicitly models relationships among molecules, properties, and between molecules and properties [34]. By integrating a task-routed mixture of experts (t-MoE) backbone with an SE(3)-equivariant encoder for physical symmetry, OmniMol achieves state-of-the-art performance across 47 of 52 ADMET property prediction tasks while providing explainable insights into all three relationship types [34].

Experimental Protocol: Implementing a Modern Molecular Representation Workflow

For researchers seeking to implement these advanced representations, the following protocol outlines a standard workflow for molecular property prediction:

Data Preparation and Curation

- Obtain molecular structures in SMILES or SDF format from public databases (ChEMBL, PubChem, ZINC)

- Standardize structures using RDKit or OpenBabel (neutralization, tautomer normalization, salt removal)

- For 3D representations, generate initial conformations using RDKit's distance geometry or OMEGA

- Apply Murcko scaffold splitting to ensure meaningful train/test separation [30]

Representation Selection and Generation

- For graph representations: Use RDKit to convert SMILES to graph objects with node features (atom type, degree, hybridization) and edge features (bond type, conjugation)

- For 3D representations: Generate GIE-RC coordinates or optimize conformations using molecular mechanics

- For set representations: Encode atoms as vectors of one-hot encoded invariants (atom type, degree, formal charge, etc.) [30]

Model Architecture and Training

- Implement GNN architectures (GIN, GAT) using PyTorch Geometric or DGL

- For multi-task learning, employ a shared backbone with task-specific heads or a mixture-of-experts