CRISPR-Cas9 for BGC Cloning: Methods, Optimization, and Applications in Natural Product Discovery

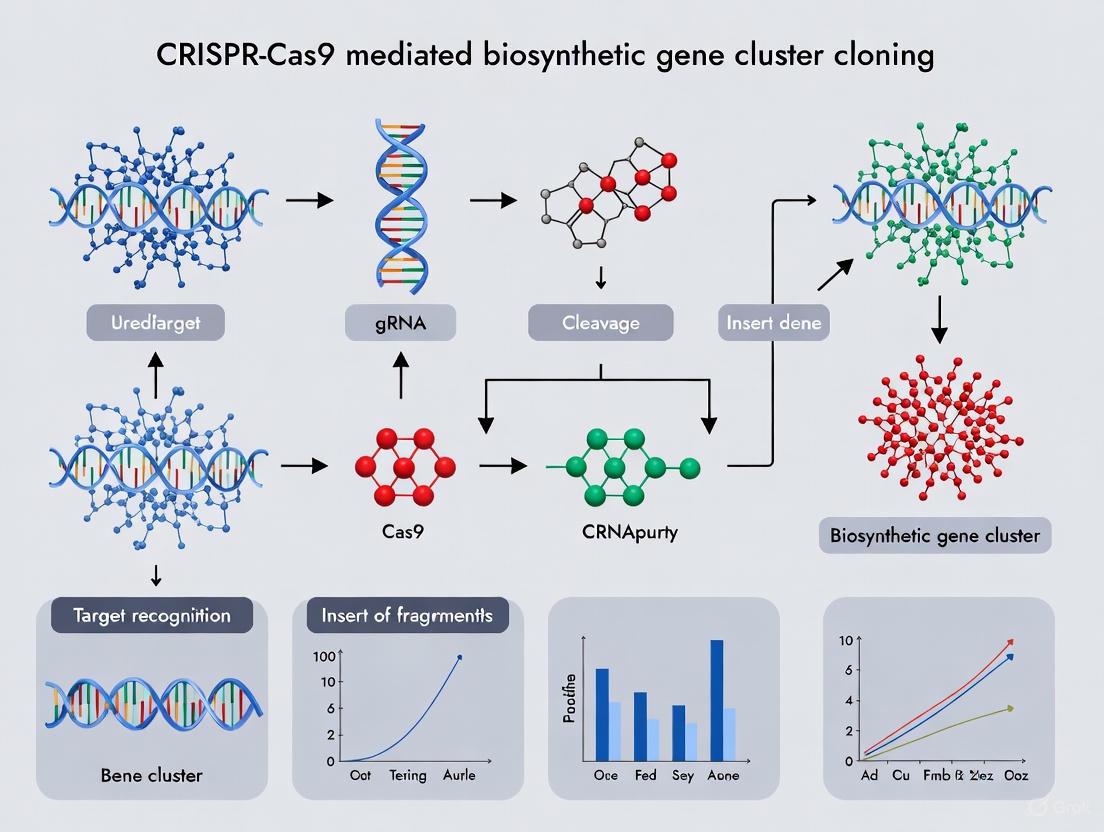

This article provides a comprehensive overview of CRISPR-Cas9 technologies for cloning and manipulating biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) from microbial genomes.

CRISPR-Cas9 for BGC Cloning: Methods, Optimization, and Applications in Natural Product Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of CRISPR-Cas9 technologies for cloning and manipulating biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) from microbial genomes. It covers foundational principles, established methods like CATCH and in vitro editing, and addresses critical challenges including off-target effects in high-GC content organisms like Streptomyces. The content explores recent advances in Cas9 engineering, specificity optimization, and emerging approaches utilizing endogenous CRISPR systems. Designed for researchers and drug development professionals, this guide synthesizes current methodologies with practical troubleshooting insights to facilitate efficient natural product discovery and metabolic engineering.

Understanding CRISPR-Cas9 Fundamentals for BGC Cloning

CRISPR-Cas9 represents a transformative genome editing tool that functions as programmable molecular scissors, enabling precise modifications to DNA sequences across diverse biological systems. This technology originates from an adaptive immune system in prokaryotes, where bacteria capture fragments of viral DNA to recognize and cleave subsequent infections [1]. The system's core components include the Cas9 nuclease enzyme and a guide RNA (gRNA), which programmably directs DNA cleavage at specific genomic locations [2]. For biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) cloning research, this programmable specificity allows researchers to precisely isolate large genomic regions encoding valuable natural products, facilitating drug discovery and metabolic engineering efforts [3] [4].

The revolutionary capability of CRISPR-Cas9 lies in its simplicity and precision compared to earlier gene-editing technologies like zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs). While these earlier systems required complex protein engineering for each new DNA target, CRISPR-Cas9 achieves specificity through simple RNA-DNA base pairing, making it significantly more accessible and efficient for genetic manipulation [1]. This programmability makes it particularly valuable for targeting BGCs, which are often large, complex, and difficult to manipulate with conventional methods.

Molecular Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

Core Functional Elements

The CRISPR-Cas9 system requires two fundamental molecular components to function as programmable DNA scissors:

- Cas9 Nuclease: A multi-domain enzyme (typically 1368 amino acids from Streptococcus pyogenes) that acts as the catalytic "scissor" component. The REC lobe (REC1 and REC2 domains) binds guide RNA, while the nuclease (NUC) lobe contains RuvC and HNH domains that cleave the non-complementary and complementary DNA strands, respectively, along with a PAM-interacting domain that initiates target recognition [1].

- Guide RNA (gRNA): A synthetic RNA molecule combining two natural RNA components: crispr RNA (crRNA), which provides target specificity through an 18-20 base pair sequence complementary to the target DNA, and trans-activating crispr RNA (tracrRNA), which serves as a binding scaffold for the Cas9 protein [1].

The PAM Requirement

A critical requirement for Cas9 function is the presence of a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) sequence immediately downstream of the target site in the DNA. For the most commonly used Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes, the PAM sequence is 5'-NGG-3', where "N" can be any nucleotide [1]. This sequence requirement can present challenges when targeting GC-rich regions, such as those frequently found in Streptomyces genomes and their BGCs, though engineered Cas9 variants are helping to address this limitation [5].

Table 1: Core Components of the CRISPR-Cas9 System

| Component | Type | Function | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Protein (Enzyme) | DNA cleavage | Contains HNH and RuvC nuclease domains; requires PAM sequence for activation |

| Guide RNA (gRNA) | RNA molecule | Target recognition | Combines crRNA (targeting) and tracrRNA (scaffold) functions |

| PAM Sequence | DNA sequence | System activation | 5'-NGG-3' for SpCas9; varies for other Cas orthologs |

The Core Mechanism: Recognition, Cleavage, and Repair

The CRISPR-Cas9 mechanism operates through three sequential stages that enable its programmable DNA editing function, each critically important for precise manipulation of biosynthetic gene clusters.

Target Recognition and Complex Assembly

The process initiates with the formation of the Cas9-gRNA ribonucleoprotein complex. The gRNA directs Cas9 to search the genome for complementary DNA sequences adjacent to a PAM sequence [1]. Once Cas9 identifies a potential PAM site, it triggers local DNA melting, allowing the gRNA to form an RNA-DNA hybrid through complementary base pairing with the target strand [1]. This PAM-dependent recognition provides the initial specificity checkpoint that ensures precise targeting—a crucial feature when working with valuable BGCs where off-target effects could be detrimental.

DNA Cleavage Mechanism

Following successful recognition and binding, the Cas9 enzyme undergoes a conformational change that activates its nuclease domains. The HNH domain cleaves the DNA strand complementary to the gRNA, while the RuvC domain cleaves the non-complementary strand [1]. This coordinated action generates a precise double-strand break (DSB) in the DNA backbone 3 base pairs upstream of the PAM sequence [1]. The result is a predominantly blunt-ended DSB that activates the cell's innate DNA repair machinery.

DNA Repair Pathways

Cellular repair of CRISPR-induced DSBs occurs primarily through two distinct mechanisms that enable different editing outcomes:

- Non-Homologous End Joining (NHEJ): An error-prone repair pathway active throughout the cell cycle that directly ligates broken DNA ends. This often results in small insertions or deletions (indels) that can disrupt gene function, useful for gene knockout applications [1].

- Homology-Directed Repair (HDR): A precise repair mechanism that uses a donor DNA template with homology to the regions flanking the break site. This pathway enables precise gene insertions, replacements, or modifications when a repair template is provided [1].

For BGC cloning and engineering, HDR provides the mechanism for precise promoter insertions, gene replacements, and other sophisticated manipulations essential for activating silent gene clusters or optimizing biosynthetic pathways [4].

Quantitative Performance Data for BGC Cloning

The application of CRISPR-Cas9 for biosynthetic gene cluster research requires understanding key performance metrics, including editing efficiency, fragment size capabilities, and fidelity across different experimental approaches.

Table 2: Performance Metrics of CRISPR-Cas9 Methods for DNA Manipulation

| Method/Application | Maximum Fragment Size | Efficiency/Fidelity | Key Advantage | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR/Cas9 + Gibson Assembly | 77 kb | 46-100% fidelity (near 100% for <50 kb) | Fast (2.5 days); technically simple; high fidelity | [3] |

| CRISPR-Cas9 Knock-in (Streptomyces) | N/A | Significantly enhanced vs. no CRISPR | Enables promoter insertion for silent BGC activation | [4] |

| Engineered Cas9-BD (Streptomyces) | >100 kb | 98.1% editing efficiency; reduced cytotoxicity | Reduced off-target effects in high-GC genomes | [5] |

| TAR-CRISPR | - | <35% fidelity | Suitable for large genomic regions | [3] |

| CATCH | ~150 kb | 2-90% fidelity | Suitable for large genomic regions | [3] |

Experimental Protocols for BGC Research

Protocol: Large-Fragment DNA Cloning via CRISPR-Cas9 and Gibson Assembly

This protocol enables direct capture and cloning of large DNA fragments (30-77 kb) from various host genomes, achieving near 100% cloning fidelity for fragments below 50 kb [3].

Materials Required:

- Purified Cas9 nuclease (commercially available or purified as in [3])

- In vitro transcribed sgRNA targeting flanking regions of target BGC

- Gibson Assembly Master Mix (commercial)

- Appropriate vector backbone

- Source genomic DNA (high molecular weight)

Procedure:

sgRNA Design and Synthesis:

- Design 20 bp oligonucleotides complementary to sequences flanking the target BGC using established resources (e.g., Zhang lab design tool)

- Generate double-stranded transcription template DNA by PCR annealing

- Perform in vitro transcription using T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit

- Purify sgRNA using clean beads [3]

Cas9 Protein Preparation:

- Express Cas9 gene in E. coli BL21(DE3) using appropriate expression vector

- Induce protein expression with 0.4 mM IPTG at 16°C for 20 hours

- Purify recombinant protein using affinity chromatography [3]

Genomic DNA Preparation:

- Culture source organisms under optimal conditions

- Harvest cells and resuspend in SET buffer with lysozyme

- Incubate at 37°C for 1 hour, then add proteinase K and SDS

- Incubate at 50°C until solution clears

- Recover genomic DNA through phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction [3]

Targeted Digestion and Assembly:

- Mix purified genomic DNA with Cas9-sgRNA ribonucleoprotein complex

- Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours to allow targeted cleavage

- Combine digested DNA with linearized vector backbone in Gibson Assembly reaction

- Incubate at 50°C for 60 minutes for seamless assembly [3]

Transformation and Verification:

- Transform assembly reaction into appropriate E. coli strain

- Select on appropriate antibiotic plates

- Verify positive clones by colony PCR and restriction analysis

- Confirm fidelity by Sanger sequencing of insertion sites

Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Promoter Knock-in for Silent BGC Activation

This protocol describes strategic promoter insertion to activate silent biosynthetic gene clusters in native Streptomyces hosts, enabling production of unique metabolites [4].

Materials:

- pCRISPomyces-2 plasmid or similar Streptomyces-optimized CRISPR vector

- Donor DNA containing strong constitutive promoter (e.g., kasO*p) with homology arms

- Target Streptomyces strain with silent BGC of interest

Procedure:

Vector Construction:

- Design sgRNA targeting insertion site upstream of BGC biosynthetic operon or pathway-specific activator

- Clone sgRNA expression cassette into CRISPR plasmid

- Prepare donor DNA containing strong constitutive promoter flanked by 1-2 kb homology arms corresponding to sequences upstream and downstream of target insertion site [4]

Transformation:

- Introduce CRISPR plasmid and donor DNA into target Streptomyces strain via conjugal transfer or protoplast transformation

- Select exconjugants on apramycin-containing plates (for pCRISPomyces-2 system) [4]

Screening and Validation:

- Screen for successful promoter insertion by colony PCR across integration junctions

- Verify promoter insertion by DNA sequencing

- Analyze metabolite production of engineered strains compared to wild type using HPLC or LC-MS

- Confirm BGC expression by RT-PCR analysis of biosynthetic genes [4]

Research Reagent Solutions for BGC Engineering

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 BGC Manipulation

| Reagent/Category | Specific Examples | Function/Application | Technical Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Plasmids | pCRISPomyces-2, pCRISPomyces-2BD | Streptomyces-optimized vectors for genome editing | Cas9-BD variant reduces cytotoxicity in high-GC genomes [5] |

| Cas9 Variants | Wild-type SpCas9, Cas9-BD, FnCas12a | DNA cleavage with different PAM specificities | Cas9-BD reduces off-target effects; FnCas12a recognizes -NTTT PAM [5] |

| Assembly Systems | Gibson Assembly Master Mix | Seamless cloning of large DNA fragments | Enables one-step assembly of Cas9-digested fragments [3] |

| Promoter Elements | kasOp, ermE | Strong constitutive promoters for BGC activation | Used for CRISPR-mediated knock-in to activate silent clusters [4] |

| Visual Screening | FveMYB10 reporter system | Visual identification of transgenic lines in plants | Native reporter for efficient screening without external markers [6] |

| Bioinformatics Tools | CHOPCHOP, CRISPResso, Cas-OFFinder | gRNA design, efficiency prediction, off-target analysis | Essential for designing specific gRNAs for unique BGC targets [7] |

Technical Considerations for BGC Applications

Successful application of CRISPR-Cas9 for biosynthetic gene cluster research requires addressing several technical challenges specific to these complex genomic regions:

GC-Rich Genome Considerations: Streptomyces genomes and their BGCs typically exhibit high GC content (70-74%), which presents challenges for CRISPR-Cas9 applications. The widely used SpCas9 recognizes 5'-NGG-3' PAM sequences that are abundant in high-GC genomes, potentially increasing off-target effects [5]. Recent engineering efforts have developed Cas9-BD, featuring polyaspartate residues at N- and C-termini, which significantly reduces off-target cleavage while maintaining high on-target efficiency in Streptomyces species [5].

Large Fragment Manipulation: Cloning large BGCs (often 30-150 kb) requires specialized approaches. The combination of CRISPR-Cas9 with Gibson assembly has demonstrated efficient cloning of fragments up to 77 kb with high fidelity [3]. For even larger fragments, methods like CATCH and CAT-FISHING can capture fragments up to 145-150 kb, though with potentially lower fidelity and more complex protocols [3].

Minimizing Cytotoxicity: High Cas9 expression can cause significant cytotoxicity in Streptomyces, limiting editing efficiency. Strategies to address this include:

- Using engineered Cas9-BD with reduced off-target activity [5]

- Employing inducible expression systems to control Cas9 timing and duration

- Utilizing Cas12a variants with different PAM requirements for specific applications [5]

Multiplexed Editing: Advanced BGC engineering often requires multiple simultaneous modifications. CRISPR-Cas9 systems enable multiplexed editing through:

- Delivery of multiple sgRNAs targeting different genomic locations

- Combinatorial promoter refactoring of multiple BGCs

- Simultaneous deletion of competing pathways and activation of target BGCs [5]

Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) represent vast reservoirs of untapped chemical diversity, encoding the production of specialized metabolites with potential applications in medicine and agriculture. However, a significant bottleneck in natural product discovery is the inability to express these clusters in their native hosts under laboratory conditions, as many remain silent or cryptic [4]. Furthermore, many potential source microorganisms are uncultivable using standard techniques, locking away their genetic potential [8]. Heterologous expression—cloning and expressing BGCs in genetically tractable host organisms—has emerged as a powerful strategy to bypass these limitations. The precision of the cloning method is paramount, as it directly influences the integrity of the captured genetic material and, consequently, the success of downstream discovery efforts. Within this field, CRISPR-Cas systems have evolved from simple gene-editing tools into versatile platforms that enable the precise targeted cloning of large and complex BGCs [9].

The Critical Need for Precision in BGC Cloning

Precise cloning is not merely a technical requirement but a fundamental determinant for the accurate reconstruction of biosynthetic pathways. Inaccurate cloning can lead to:

- Truncated or Chimeric Clusters: Resulting in non-functional pathways or the production of incorrect metabolites.

- Disruption of Regulatory Elements: Silent BGCs often require their native regulatory context for activation; imprecise cloning can destroy these subtle controls.

- Failed Heterologous Expression: The heterologous host may lack the machinery to correct errors introduced during cloning.

Advanced cloning methods, particularly those leveraging CRISPR-Cas systems, address these challenges by enabling sequence-specific excision of BGCs from complex genomic DNA, ensuring that the boundaries of the cloned fragment exactly match the bioinformatically predicted cluster [9].

Application Note: CAPTURE - A CRISPR-Cas12a Based Cloning Protocol

The Cas12a-assisted precise targeted cloning using in vivo Cre-lox recombination (CAPTURE) method exemplifies how CRISPR technology can be harnessed for high-efficiency, precise cloning of large BGCs [9].

Principle and Workflow

The CAPTURE method utilizes the programmable nuclease Cas12a to excise the target BGC from purified genomic DNA. The excised linear fragment is then assembled with a specialized vector system and circularized in vivo using Cre-loxP site-specific recombination, a process far more efficient than in vitro ligation for large DNA molecules [9].

The workflow for this targeted cloning approach is illustrated below:

Detailed Experimental Protocol

Step 1: In Vitro Cas12a Digestion of Genomic DNA

- Design Cas12a guide RNAs (crRNAs): Design two crRNAs that target sequences immediately flanking the BGC of interest. The target sites should define the precise start and end of the cluster.

- Prepare genomic DNA: Isolate high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from the producer organism and embed it in low-melt agarose plugs to prevent mechanical shearing.

- Perform Cas12a digestion: Set up a reaction containing the genomic DNA plug, purified Cas12a enzyme, and the synthesized crRNAs. Incubate to allow for specific cleavage, which releases the target BGC as a large linear DNA fragment.

Step 2: Preparation of DNA Receivers by PCR

- Amplify receiver fragments: Perform PCR to amplify two DNA "receiver" fragments from a universal receiver plasmid. These receivers contain:

- An origin of replication (

ori) for E. coli. - A selectable marker (e.g., an antibiotic resistance gene).

loxPsites at their termini for subsequent recombination.- Elements for heterologous expression (e.g., origins for conjugation, integration sites, or strong promoters).

- An origin of replication (

- Purify PCR products: Gel-purify the amplified receiver fragments to ensure high concentration and purity.

Step 3: T4 Polymerase Exo + Fill-in DNA Assembly

- Set up assembly reaction: Combine the Cas12a-released BGC fragment with the two purified DNA receivers.

- Add T4 DNA polymerase: Initiate the assembly using T4 DNA polymerase, which possesses both exonuclease and fill-in synthesis activities. This creates complementary single-stranded overhangs on all fragments, facilitating their annealing into a single linear molecule.

Step 4: In Vivo Circularization via Cre-lox Recombination

- Transform assembly product: Introduce the linear assembly product into an E. coli strain harboring a helper plasmid. This plasmid constitutively expresses Cre recombinase and the phage lambda Red Gam protein (which protects linear DNA from degradation) [9].

- Select for clones: Plate the transformation on selective media. Within the E. coli cells, the Cre recombinase catalyzes site-specific recombination between the

loxPsites on the linear molecule, efficiently circularizing it into a stable plasmid. - Validate clones: Screen resulting colonies by colony PCR or restriction digest to confirm the correct clone. The helper plasmid can be easily cured due to its temperature-sensitive origin of replication.

Performance Data

The CAPTURE method has demonstrated remarkable efficiency and robustness, as shown in the following performance summary:

Table 1: Performance Metrics of the CAPTURE Cloning Method [9]

| Metric | Performance | Experimental Details |

|---|---|---|

| Cloning Efficiency | ~100% | Successfully cloned 47 out of 47 targeted BGCs |

| BGC Size Range | 10 - 113 kb | Demonstrates capability for very large clusters |

| Host Organisms | Actinomycetes & Bacilli | Applicable across different bacterial taxa |

| Key Discovery | 15 novel natural products | Includes antimicrobial bipentaromycins A-F |

Advanced CRISPR-Cas Strategies for BGC Activation and Editing

Beyond direct cloning, CRISPR-Cas systems can be deployed to activate and edit BGCs directly in their native hosts.

CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Promoter Knock-in

For silent BGCs, a powerful one-step strategy involves using CRISPR-Cas9 to insert strong, constitutive promoters upstream of key biosynthetic genes or pathway-specific activators [4].

- Procedure: A donor DNA template containing a strong promoter (e.g.,

kasOp*) is co-introduced with a Cas9-sgRNA complex designed to create a double-strand break near the target integration site. The cell's homology-directed repair (HDR) machinery uses the donor DNA to repair the break, thereby integrating the promoter. - Outcome: This method has been used to activate diverse silent BGCs in Streptomyces species, leading to the production of unique metabolites, including a novel pentangular type II polyketide [4].

Engineered Cas9 Systems for Improved Editing in GC-Rich Hosts

A significant challenge in editing actinomycete genomes (which have high GC content) is Cas9 cytotoxicity and off-target cleavage. Recent work has addressed this by engineering the Cas9 protein itself.

- Cas9-BD: A modified Cas9 with polyaspartate tags added to its N- and C-termini shows dramatically reduced off-target cleavage while maintaining high on-target activity [5].

- Application: Cas9-BD was successfully used for multiplexed genome editing in Streptomyces and facilitated the development of an in vivo BGC capturing method for clusters larger than 100 kb, showcasing its versatility and reduced toxicity [5].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Based BGC Cloning

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Their Applications

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| Cas12a (Cpf1) Nuclease | Programmable nuclease for precise genomic DNA digestion; often requires a T-rich PAM site. | Precise excision of BGCs from genomic DNA in the CAPTURE protocol [9]. |

| Cre-lox Recombination System | Site-specific recombination system for efficient circularization of linear DNA fragments in vivo. | Final plasmid assembly step in the CAPTURE method, greatly improving efficiency for large DNA fragments [9]. |

| Engineered Cas9-BD | A modified Cas9 with reduced off-target effects and cytotoxicity in high-GC content hosts. | Multiplexed genome editing and large BGC capture in Streptomyces without significant cell death [5]. |

| T4 DNA Polymerase | Enzyme with exonuclease and fill-in synthesis activities for seamless DNA assembly. | Used in the CAPTURE method to join the BGC fragment with vector pieces without the need for homologous overlaps [9]. |

| Helper Plasmids (e.g., pBE14) | Plasmid providing transient expression of Cre recombinase and Red Gam proteins in E. coli. | Essential for the in vivo circularization and stability of the cloned BGC construct [9]. |

| Heterologous Expression Platforms (e.g., Micro-HEP) | Engineered chassis strains and systems for BGC modification, transfer, and expression. | Platform using recombinase-mediated cassette exchange (RMCE) for efficient expression of foreign BGCs in S. coelicolor [10]. |

The convergence of precise cloning technologies and CRISPR-Cas systems has created a powerful paradigm for natural product discovery. Methods like CAPTURE demonstrate that large BGCs can be cloned with near-perfect efficiency, directly enabling the discovery of novel chemical entities [9]. The continued evolution of these tools—including engineered nucleases with higher fidelity and advanced heterologous expression platforms—promises to further accelerate the unlocking of Nature's chemical repertoire, paving the way for new therapeutics and agrochemicals. The precision of the initial clone is and will remain the critical first step on the path from genetic sequence to valuable molecule.

The discovery that a bacterial immune mechanism could be repurposed into a programmable genome engineering tool represents one of the most significant breakthroughs in modern biotechnology. The Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats (CRISPR) and CRISPR-associated protein 9 (Cas9) system is derived from an adaptive immune system in bacteria that captures and stores genetic memories of past viral infections [11] [12]. When confronted with subsequent infections, bacteria transcribe these stored sequences into RNA molecules that guide Cas nucleases to cleave the DNA of invading viruses, thus disabling them [12]. This natural system was adapted for genome editing by engineering a single guide RNA (sgRNA) that directs the Cas9 nuclease to a specific DNA sequence in a cell's genome, resulting in a targeted double-stranded break (DSB) [13]. The simplicity, cost-effectiveness, and high efficiency of this two-component system—Cas9 enzyme and guide RNA—have made it a revolutionary tool in genetic engineering, surpassing previous technologies like zinc finger nucleases (ZFNs) and transcription activator-like effector nucleases (TALENs) [14] [13].

This article details the application of CRISPR-Cas9 technology specifically for biosynthetic gene cluster (BGC) cloning, a critical process in natural product discovery and synthetic biology. BGCs are stretches of DNA that encode the production of biologically active compounds, such as antibiotics, and often span tens to hundreds of kilobases [3]. Their large size makes traditional cloning methods challenging. We provide a detailed protocol for a CRISPR-Cas9-mediated large-fragment assembly method that efficiently clones these substantial DNA segments for heterologous expression and research [15] [3].

Application Notes: CRISPR-Cas9 in BGC Cloning

The Challenge of Large DNA Fragment Cloning

The cloning of large DNA fragments, such as those encompassing entire biosynthetic gene clusters, is fundamental to both basic and applied research, including synthetic genome construction and natural product discovery [3]. Conventional cloning methods face significant limitations when dealing with fragments over 10 kb. Techniques like Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) and Exonuclease combined with RecET recombination (ExoCET) often suffer from technical complexity, low efficiency, long cycling times, and reliance on specific restriction sites [3]. The CRISPR-Cas9-mediated large-fragment assembly method overcomes these hurdles by combining the precision of CRISPR with the seamless assembly capability of Gibson assembly, enabling direct capture and cloning of large genomic regions up to 77 kb with high fidelity and in a shorter timeframe [15] [3].

Comparative Analysis of Large-Fragment Cloning Methods

Table 1: Comparison of Large-Fragment DNA Cloning Methods

| Method | Maximum DNA Fragment Size | Fidelity | Cycle Time | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| CRISPR-Cas9 + Gibson (This Method) | ~80 kb | 46–100% | ~2.5 days | Technically easier; high fidelity; short cycle; can clone fragments from different sources [3] | Fidelity decreases for larger fragments [3] |

| LLHR | ~52 kb | <~50% | ~3 days | Technically easier; suitable for small- and mid-sized BGCs [3] | High false positive rate; difficult for large BGCs [3] |

| ExoCET | ~106 kb | 4–100% | ~3 days | Technically easier; uses short homologous arms [3] | Low efficiency for cloning large-size BGCs [3] |

| TAR-CRISPR | - | <35% | ~7 days | Cas9-facilitated; suitable for large genomic regions [3] | Technically challenging; uses yeast spheroplasts; false positives [3] |

| CATCH | ~150 kb | 2–90% | ~4 days | Suitable for cloning large genomic regions [3] | Requires careful preparation of genomic DNA in gel [3] |

| CAT-FISHING | ~145 kb | 8–55% | 3–4 days | Suitable for regions with high GC content [3] | Low efficiency [3] |

Quantitative Performance of the CRISPR-Cas9 Method

The efficacy of the CRISPR-Cas9 assembly method has been quantitatively demonstrated for DNA fragments of varying sizes. The table below summarizes the cloning fidelity achieved for different fragment lengths, showcasing its reliability for a wide range of applications [3].

Table 2: Cloning Fidelity of the CRISPR-Cas9 Large-Fragment Assembly Method

| DNA Fragment Size | Cloning Fidelity |

|---|---|

| 15 kb | Near 100% |

| 30 kb | Near 100% |

| 50 kb | Near 100% |

| 60 kb | 46% |

| 77 kb | 46% |

Diagram 1: Evolution from immunity to tool.

Experimental Protocols

CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Large-Fragment Assembly

This protocol describes a fast and efficient platform for the direct capture and cloning of large DNA fragments (30-77 kb) from genomic DNA, achieving near 100% fidelity for fragments below 50 kb [3]. The entire process can be completed in approximately 2.5 days.

sgRNA Design and In Vitro Transcription

- sgRNA Design: Design 20 bp oligonucleotides specific to the flanks of the target genomic region using established design resources (e.g., from the Zhang lab: https://www.zlab.bio/Resources-guidedesign) [3]. Two sgRNAs are required to excise the large fragment of interest.

- Template Generation: Generate the double-stranded DNA template for sgRNA transcription via PCR annealing. Use primer sgRNA-E-F with a T7 promoter sequence and sgRNA-scaffold-R to amplify the scaffold [3].

- In Vitro Transcription: Perform in vitro transcription using a commercial T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit according to the manufacturer's instructions [3].

- RNA Purification: Purify the transcribed sgRNA using clean beads (e.g., VAHTS RNA Clean Beads) following the kit's protocol. The purified sgRNA can be stored at -80°C [3].

Expression and Purification of Cas9 Protein

- Vector Construction: Clone the Cas9 gene into a protein expression vector (e.g., pET28a) using standard molecular biology techniques, ensuring it is flanked by the appropriate restriction sites (e.g., SalI and NcoI) [3].

- Transformation and Expression: Transform the constructed plasmid into an E. coli expression strain like BL21(DE3). Grow a 1 L culture and induce protein expression with 0.4 mM IPTG when the OD600 reaches 0.6-0.8. Induce at 16°C for 20 hours [3].

- Protein Purification: Purify the recombinant Cas9 protein using a standard chromatography system (e.g., AKTA). Confirm purity and concentration, and store in a suitable buffer [3].

Preparation of Genomic DNA

- Cell Culture and Lysis: Culture the source organism (e.g., Streptomyces ceruleus or B. subtilis) in appropriate media. Harvest cells by centrifugation and resuspend in SET buffer. Add lysozyme and incubate at 37°C for 1 hour, followed by the addition of proteinase K and SDS, incubating at 50°C until the solution clears [3].

- DNA Extraction and Precipitation: Add 5 M NaCl to the lysate. Extract the genomic DNA using phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol and recover the aqueous phase. Precipitate the DNA with ethanol and sodium acetate, and wash the pellet with 75% ethanol [3]. The resulting high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA is crucial for success.

In Vitro Cleavage and Gibson Assembly

- Cas9 Cleavage Reaction: Set up a reaction mixture containing the purified genomic DNA, the two purified sgRNAs, and the Cas9 nuclease in a suitable reaction buffer. Incubate to allow for precise cleavage at the target sites, thereby excising the large fragment of interest [3].

- Gibson Assembly: Combine the Cas9-cleaved DNA fragment with a linearized cloning vector. Use a commercial Gibson Assembly Master Mix to seamlessly assemble the fragment and vector. This isothermal assembly method uses a 5' exonuclease, a DNA polymerase, and a DNA ligase to join the pieces with high efficiency [3].

- Transformation and Screening: Transform the assembled product into competent E. coli cells. Screen the resulting colonies by colony PCR and/or restriction digestion to identify positive clones containing the correct large DNA insert [3].

Diagram 2: BGC cloning workflow.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Large-Fragment Cloning

| Reagent / Material | Function / Role in the Protocol | Example / Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | The engine of the system; creates double-stranded breaks at the target DNA site specified by the sgRNA [11] [3]. | Recombinantly expressed and purified S. pyogenes Cas9. |

| sgRNAs | Provides the targeting specificity; a synthetic fusion of crRNA and tracrRNA that directs Cas9 to the intended genomic locus [11] [16] [14]. | In vitro transcribed (IVT) using a T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit [3]. |

| T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit | Generates large quantities of sgRNA from a DNA template for in vitro use [3]. | Commercial kit (e.g., from Vazyme). |

| VAHTS RNA Clean Beads | Purifies transcribed sgRNA, removing unincorporated nucleotides and enzymes, which is critical for downstream efficiency [3]. | Solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) beads. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | Enables seamless, one-pot assembly of multiple DNA fragments (the excised BGC and the linearized vector) without relying on restriction sites [15] [3]. | Contains a 5' exonuclease, DNA polymerase, and DNA ligase. |

| pET28a Vector | A common protein expression vector used for the heterologous expression of the Cas9 protein in E. coli [3]. | Plasmid with T7 lac promoter, kanamycin resistance. |

| E. coli BL21(DE3) | A robust bacterial strain designed for high-level protein expression from vectors containing the T7 lac promoter [3]. | Competent cells for transformation and protein production. |

The repurposing of the prokaryotic CRISPR-Cas immune system into a precise genome engineering tool has fundamentally transformed genetic research. The CRISPR-Cas9-mediated large-fragment assembly method detailed herein provides researchers with a powerful, efficient, and reliable strategy to clone large biosynthetic gene clusters. This capability is indispensable for accelerating the discovery and production of novel natural products, functional genomics studies, and the construction of synthetic genomes. As the field progresses, further refinements in guide RNA design, Cas protein engineering, and delivery methods will continue to expand the boundaries of what is possible with this versatile technology.

The cloning and manipulation of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) are critical for accessing the vast potential of natural products for drug discovery and development. Traditional methods for BGC cloning, such as Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) and Exonuclease combined with RecET recombination (ExoCET), have been limited by complex operational procedures, dependence on restriction sites, and challenges in scaling [17]. The advent of CRISPR-Cas9 technology has revolutionized this field by offering a fundamentally different approach based on RNA-guided DNA recognition, providing unprecedented advantages in specificity, versatility, and scalability for BGC research. This Application Note details these advantages within the context of biosynthetic gene cluster cloning and provides validated protocols for implementing CRISPR-Cas9 in your research workflow.

Comparative Analysis: CRISPR-Cas9 vs. Traditional Methods

The table below summarizes the key differences between CRISPR-Cas9 and traditional gene editing platforms, highlighting the transformative advantages of CRISPR-Cas9 for BGC cloning.

Table 1: Comparison of Gene Editing Platforms for BGC Cloning

| Feature | CRISPR-Cas9 | Traditional Methods (ZFNs, TALENs) | BGC Cloning Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Targeting Mechanism | RNA-guided (gRNA) [18] | Protein-based (engineered zinc fingers/TALE repeats) [18] [19] | Simple gRNA redesign for different BGCs vs. complex protein re-engineering |

| Ease of Design & Use | Simple, rapid gRNA design (days) [18] | Complex, labor-intensive protein engineering (weeks-months) [18] | Accelerates pipeline from genomic DNA sequence to cloned construct |

| Multiplexing Capacity | High (multiple gRNAs simultaneously) [18] | Limited (labor-intensive and costly) [18] | Enables simultaneous cloning or editing of multiple BGCs or regions within a large BGC |

| Precision & Specificity | Moderate to high; subject to off-target effects [18] | High; well-validated, lower off-target risks [18] [19] | Critical for obtaining intact, unmodified BGCs; improved Cas9 variants (e.g., Cas9-BD) mitigate this issue [20] |

| Scalability & Throughput | High; ideal for high-throughput experiments [18] | Limited [18] | Enables library-scale cloning of BGCs from metagenomic or genomic DNA |

| Cost Efficiency | Low [18] | High [18] | Makes large-scale BGC cloning projects financially viable |

For BGC cloning, the simple guide RNA (gRNA) design is a paramount advantage over traditional methods. Researchers can quickly design gRNAs to target the flanks of a BGC of interest, whereas traditional methods like ZFNs and TALENs require intricate protein engineering for each new target, a process that is both time-consuming and expensive [18]. Furthermore, CRISPR-Cas9's multiplexing capability allows for the simultaneous targeting of multiple genomic loci, enabling the cloning of large BGCs as a single fragment or the coordinated manipulation of multiple genetic elements within a cluster [18] [20].

Key Advantages in BGC Research

Enhanced Specificity with Engineered Cas Variants

A primary concern in BGC cloning is the precise excision of the entire cluster without internal damage. While early CRISPR-Cas9 systems showed some off-target activity, advanced engineered variants now offer superior fidelity. For instance, Cas9-BD, a modified Cas9 engineered for use in high-GC content genomes like those of Streptomyces, demonstrates decreased off-target binding and cytotoxicity compared to the wild-type protein [20]. This is crucial for accurately cloning BGCs from actinomycetes, a major source of bioactive natural products, without introducing unwanted mutations that could disrupt biosynthetic pathways.

Unparalleled Versatility in Application

CRISPR-Cas9's utility in BGC research extends far beyond simple knockout or excision. Its versatility enables a wide range of applications:

- Direct BGC Cloning: Methods like the one described by [17] combine in vitro Cas9 cleavage of genomic DNA with Gibson assembly to directly clone large fragments (30-77 kb) into vectors with high fidelity.

- BGC Refactoring and Activation: The ACTIMOT (Advanced Cas9-mediaTed In vivo MObilization and mulTiplication of BGCs) technology uses CRISPR-Cas9 to mobilize and amplify cryptic BGCs, providing access to untapped chemical diversity from bacterial genomes [21].

- Multiplexed Genome Editing: Engineered Cas9 systems can be used for simultaneous BGC deletions, refactoring, and gene activation in a single experiment, dramatically accelerating strain engineering for improved metabolite production [20].

Superior Scalability for High-Throughput Workflows

The simplicity of programming CRISPR-Cas9 with custom gRNAs makes it inherently scalable. This allows researchers to move from cloning single BGCs to undertaking projects aimed at capturing entire BGC libraries. The ability to process multiple samples in parallel using a standardized molecular workflow makes CRISPR-based methods ideal for high-throughput functional genomics screens and the systematic exploration of biosynthetic diversity [18] [17]. This scalability is a significant advantage over traditional methods, which are difficult and costly to parallelize.

Experimental Protocol: CRISPR-Cas9-Mediated Large-Fragment BGC Cloning

This protocol, adapted from [17], details a robust method for cloning large BGCs (e.g., 40 kb) from genomic DNA using CRISPR-Cas9 cleavage followed by Gibson assembly.

Diagram 1: BGC cloning workflow.

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents for CRISPR-Cas9 BGC Cloning

| Item | Function/Description | Example/Source |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Engineered protein for targeted DNA cleavage. | Purified S. pyogenes Cas9 (e.g., NEB). For high-GC content hosts, use engineered variants like Cas9-BD [20]. |

| gRNA | Synthetic RNA guiding Cas9 to target DNA sequences. | Synthesized via in vitro transcription from a DNA template [17]. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | Enzymatic mix for seamless, simultaneous assembly of multiple DNA fragments. | Commercial kit (e.g., NEB HiFi Gibson Assembly). |

| Vector Backbone | Cloning vector with appropriate homology arms and selection marker. | Designed with 20-40 bp homology arms matching the ends of the target BGC fragment [17]. |

| Host Genomic DNA | High-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA from the source organism. | Prepared using standard phenol-chloroform extraction [17]. |

Step-by-Step Procedure

Step 1: gRNA Design and Synthesis

- Design gRNAs targeting ~20 bp sequences immediately flanking the BGC of interest using bioinformatics tools (e.g., from the Zhang lab:

https://www.zlab.bio/Resources-guidedesign) [17]. - Synthesize gRNAs via in vitro transcription. Generate the DNA template by PCR annealing, then perform transcription using a commercial kit (e.g., T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit, Vazyme). Purify the resulting sgRNA using clean beads [17].

Step 2: Cas9 Protein Expression and Purification

- Clone the Cas9 gene into an expression vector (e.g., pET28a) and transform into an E. coli expression strain like BL21(DE3).

- Induce protein expression with 0.4 mM IPTG when OD600 reaches 0.6-0.8. Incubate at 16°C for 20 hours.

- Purify the Cas9 protein using a standard affinity chromatography system (e.g., ÄKTA) [17].

Step 3: Preparation of High-Molecular-Weight Genomic DNA

- Culture the source organism (e.g., Streptomyces) under optimal conditions.

- Harvest cells and lyse using a combination of lysozyme, proteinase K, and SDS.

- Purify genomic DNA through phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction and recover via ethanol precipitation [17].

Step 4: In Vitro Cas9 Cleavage of Genomic DNA

- Set up the cleavage reaction:

- 800 nM purified Cas9 protein

- 400 nM of each sgRNA (flanking the BGC)

- 1x NEB Buffer 3.1

- Recombinant ribonuclease inhibitor

- 0.02-0.04 nM genomic DNA

- Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours to allow for targeted cleavage and release of the BGC fragment from the genome [17].

Step 5: Purification of Cleaved DNA Fragment

- Add an equal volume of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol to the cleavage reaction.

- Centrifuge and collect the aqueous supernatant.

- Precipitate the DNA by adding 3 M sodium acetate and anhydrous ethanol.

- Wash the pellet with 75% ethanol, air-dry, and resuspend in nuclease-free water [17].

Step 6: Gibson Assembly

- Combine the following in a single tube:

- Purified BGC fragment (from Step 5)

- Linearized vector backbone (with homology arms matching the BGC fragment ends)

- Gibson Assembly Master Mix

- Incubate at 50°C for 30-60 minutes to assemble the BGC fragment into the vector [17].

Step 7: Transformation and Validation

- Transform the assembly reaction into a competent E. coli strain suitable for large plasmid maintenance.

- Screen colonies by colony PCR and/or restriction digest to confirm correct insertion.

- Validate positive clones by Sanger sequencing across the assembly junctions and, if possible, by whole-plasmid sequencing to ensure BGC integrity [17].

CRISPR-Cas9 technology represents a paradigm shift in the cloning and study of biosynthetic gene clusters. Its specificity, enhanced by novel Cas variants, its versatility in enabling cloning, refactoring, and multiplexed editing, and its inherent scalability for high-throughput projects provide a powerful and streamlined toolkit that outperforms traditional methods. The protocols outlined herein offer a reliable pathway for researchers to leverage these advantages, accelerating the discovery and engineering of novel natural products for therapeutic applications.

Practical Guide: CRISPR-Cas9 Methods for BGC Capture and Assembly

Cas9-Assisted Targeting of Chromosome Segments for Large Fragments

The cloning of large DNA segments, particularly biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), is fundamental to synthetic biology and natural product discovery [22] [3]. These clusters, which can span tens to hundreds of kilobases, encode the production of valuable compounds, including pharmaceuticals, antibiotics, and biofuels [3] [17]. Traditional cloning methods, such as PCR-based amplification and restriction enzyme digestion, face significant limitations when applied to large genomic targets. Standard PCR struggles with fragments exceeding 10-35 kb, while restriction enzyme approaches depend on the availability of unique flanking sites, which are often absent in complex genomes [22] [3].

The Cas9-Assisted Targeting of CHromosome segments (CATCH) method overcomes these hurdles by leveraging the programmability of the CRISPR-Cas9 system for the precise excision of large genomic regions directly from native chromosomes [22] [23] [24]. This technique enables the one-step targeted cloning of sequences up to 100-150 kb, providing a powerful tool for capturing extensive gene clusters that are otherwise expensive to synthesize or difficult to isolate using conventional techniques [22]. The application of CATCH within a broader CRISPR-Cas9 framework significantly accelerates the cloning and heterologous expression of BGCs, thereby streamlining the pathway to novel bioactive compound discovery [3] [5].

CATCH Cloning Workflow

The following diagram illustrates the streamlined CATCH cloning procedure, from guide RNA design to the generation of a clone harboring the target large DNA fragment.

Key Research Reagent Solutions

The successful implementation of CATCH cloning relies on a suite of specialized reagents and materials. The following table details the essential components and their functions within the protocol.

| Reagent/Material | Function in CATCH Protocol | Key Details |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | Executes precise double-strand breaks at chromosomal target sites. | Requires final concentration of 0.02–0.1 mg/ml for in-gel digestion [22]. A modified version (Cas9-BD) reduces off-target cleavage in high-GC genomes [5]. |

| sgRNAs | Guides Cas9 to specific flanking genomic loci. | Critical to use >30 ng/μl final concentration. Designed using 20 bp protospacers complementary to target flanks [22] [3]. |

| Low-Melting Point Agarose | Protects high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from mechanical shearing. | Cells are lysed, and DNA is purified within gel plugs [22] [24]. |

| BAC Cloning Vector | Provides backbone for propagation and selection of cloned insert. | Vector is engineered with 30 bp terminal sequence overlaps for Gibson assembly with the target DNA [22]. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | Seamlessly ligates the excised genomic fragment to the vector. | Contains T5 5'–3' exonuclease, Taq DNA ligase, and a high-fidelity polymerase [22] [3]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

sgRNA Design and Preparation

- Design: Select two target sites that flank the genomic region of interest. Each target requires a 20-nucleotide protospacer sequence adjacent to a 5'-NGG-3' Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM). The PAM sites should be oriented outward relative to the target segment [22].

- Synthesis: Generate double-stranded DNA templates via PCR annealing. Synthesize sgRNAs using a T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit, followed by purification with clean beads [3] [17].

Genomic DNA Preparation in Agarose Plugs

- Embed Cells: Resuspend bacterial cells at an optimal concentration of ~5 × 10⁸ cells/mL in low-melting-point agarose and form plugs.

- Lysis: Treat plugs successively with lysozyme and proteinase K to lyse cells and digest proteins, leaving intact genomic DNA protected within the agarose matrix [22] [3].

- Washing: Wash plugs thoroughly with buffer to remove cellular debris and enzymes [22].

In-gel Cas9 Digestion

- Pre-assemble Cas9-sgRNA Complex: Incubate Cas9 nuclease with the pair of sgRNAs (each at 400 nM) in an appropriate reaction buffer at 37°C for 20 minutes to form ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes [3] [17].

- Digest Genomic DNA: Soak the agarose plug containing the genomic DNA in the RNP complex solution. Incubate at 37°C for 1-2 hours to allow for Cas9 diffusion and targeted excision of the DNA fragment [22].

DNA Recovery and Vector Ligation

- Recover DNA: Melt the digested plug, treat with agarase, and purify the DNA via ethanol precipitation [22]. Alternative methods using phenol-chloroform extraction can also be employed [17].

- Gibson Assembly: Mix the purified, cleaved DNA fragment with a linearized BAC vector containing 30 bp homologous overlaps in a Gibson assembly reaction. Incubate at 50°C for 15–60 minutes [22] [3].

Transformation and Clone Validation

- Transformation: Introduce the assembly mixture into electrocompetent E. coli cells via electroporation.

- Selection and Screening: Plate cells on selective media (e.g., containing chloramphenicol). Screen resulting colonies for correct inserts using methods such as PCR and junction sequencing [22].

- Final Validation: Purify BAC DNA from positive clones and validate the insert size by pulsed-field gel electrophoresis (PFGE) after linearization [22].

Performance and Fidelity Data

The performance of CATCH cloning is highly dependent on the size of the target DNA fragment. The table below summarizes key experimental outcomes, highlighting the relationship between insert size and cloning success.

| Target DNA Size | Cloning Efficiency | Key Applications Demonstrated | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| 30 - 50 kb | High efficiency (50-100 colonies); near 100% fidelity for <50 kb fragments. | Cloning of lacZ from E. coli; fengycin cluster from B. subtilis [22] [3]. | [22] [3] |

| 75 - 100 kb | Moderate efficiency; positive clones obtained for 100 kb targets. | Targeted cloning of large bacterial genomic segments [22]. | [22] |

| >150 kb | Low efficiency; upper limit demonstrated is ~150 kb (1 positive clone) to 200 kb (0 clones). | Demonstration of method's maximum capacity [22]. | [22] |

| 40 kb (from Streptomyces) | Successfully cloned with high fidelity. | Capture of BGCs from high-GC content actinomycetes [3]. | [3] |

Discussion and Implementation

The CATCH method represents a significant leap in large-fragment cloning technology. Its primary advantage lies in its independence from restriction enzymes, allowing for the targeted cloning of near-arbitrary sequences from bacterial genomes with high specificity [22] [24]. The entire procedure can be completed in 1-2 days with approximately 8 hours of hands-on bench time, offering a rapid and cost-effective alternative to de novo gene synthesis for large constructs [22].

When implementing this protocol, several factors are critical for success. The preparation of high-quality, high-molecular-weight DNA within agarose plugs is essential to minimize shearing. The concentration and activity of the Cas9-sgRNA complex are also crucial; insufficient sgRNA can lead to incomplete digestion [22]. Recent advancements have simplified the workflow by replacing traditional gel extraction with automated DNA size selection systems [24], and have enhanced specificity for challenging genomes, such as those of Streptomyces, through engineered Cas9 variants (e.g., Cas9-BD) that reduce off-target cleavage [5].

A notable limitation of the original CATCH protocol is the decreasing efficiency for fragments larger than 150 kb. Furthermore, the initial requirement for in-gel digestion and PFGE, though mitigated by newer extraction methods, can be technically demanding [3] [24]. For cloning in eukaryotic systems or for in vivo applications, alternative methods like TAR cloning or the novel CloneSelect system, which uses base editing for precise clone isolation, may be more suitable [25] [26].

In conclusion, CATCH cloning is an powerful molecular tool that has been robustly adopted for capturing BGCs from both model organisms and genetically complex bacteria. Its integration into the synthetic biology pipeline greatly facilitates the exploration and exploitation of natural product diversity for drug discovery and bioproduction.

The refactoring of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs) is a critical process in synthetic biology for activating and optimizing the production of valuable natural products, such as antibiotics and anticancer agents. In Vitro CRISPR Editing (ICE) represents a transformative methodology that combines the precision of the CRISPR-Cas system with the power of in vitro DNA assembly to directly capture and reassemble large DNA fragments from genomic sources. This approach effectively addresses a significant challenge in natural product discovery: the difficulty in cloning large BGCs, which often span tens to hundreds of kilobases [3]. Traditional cloning methods face limitations due to restricted enzyme sites and operational complexity, but the ICE method enables efficient, seamless construction of large DNA constructs from diverse and distant biological sources. When framed within the broader thesis of CRISPR-Cas9 applications for BGC cloning, ICE emerges as a robust, rapid, and high-fidelity platform that accelerates the prototyping of genetic designs for drug discovery and development.

Key Principles and Advantages of the ICE Workflow

The fundamental innovation of the ICE protocol lies in its integration of CRISPR-mediated cleavage with Gibson assembly. This combination creates a highly specific and efficient pipeline for isolating large genomic fragments and inserting them into suitable vectors for heterologous expression. The process begins with the design of guide RNAs (gRNAs) that flank the target BGC. The Cas9 nuclease, complexed with these gRNAs, performs precise double-strand breaks at the designated sites, excising the entire gene cluster from the native genome [3]. The resulting linear fragment is then purified and subsequently assembled into a linearized vector using an in vitro recombination system, which seamlessly joins the homologous ends.

This methodology offers several distinct advantages over conventional techniques, as detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: Comparison of Large-Fragment DNA Cloning Methods

| Method | Maximum DNA Fragment Size | Fidelity (Success Rate) | Time Cycle | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ICE (This Method) | ~80 kb | 46% - 100% (Near 100% for <50 kb) | ~2.5 days | Technically easier; short cycle; high fidelity; no agarose gel embedding required [3]. | Efficiency decreases for fragments >50 kb [3]. |

| CATCH | ~150 kb | 2% - 90% | ~4 days | Suitable for very large genomic regions [3]. | Requires careful preparation of genomic DNA in gel; technically challenging [3]. |

| CAT-FISHING | ~145 kb | 8% - 55% | 3-4 days | Suitable for cloning regions with high GC content [3]. | Low overall efficiency [3]. |

| ExoCET | ~106 kb | 4% - 100% | ~3 days | Technically easier; uses short homologous arms for recombination [3]. | Low efficiency for cloning large-size BGCs; limited by restriction sites [3]. |

| TAR-CRISPR | - | <35% | ~7 days | Cas9-facilitated high-efficiency cloning in yeast [3]. | Technically challenging; requires yeast spheroplasts; some false positives [3]. |

The quantitative data from Table 1 underscores the operational efficiency of the ICE method. Its capability to clone fragments up to 77 kb with high fidelity, coupled with a significantly shorter turnaround time of approximately 2.5 days, makes it a superior choice for rapid prototyping of BGCs [3].

Detailed ICE Protocol for BGC Refactoring

Reagent and Material Preparation

The following toolkit is essential for the execution of the ICE protocol. Critical reagents must be molecular biology grade, and nuclease-free water should be used for all enzymatic reactions.

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for ICE

| Item | Function/Description | Key Details/Specifications |

|---|---|---|

| Cas9 Nuclease | CRISPR-associated endonuclease for targeted DNA cleavage. | Purified S. pyogenes Cas9 protein. Can be expressed and purified in-house from E. coli BL21(DE3) using a pET28a vector [3]. |

| sgRNA | Synthetic guide RNA that directs Cas9 to specific genomic loci. | Designed using resources like the Zhang lab (zlab.bio). Synthesized via in vitro transcription and purified with RNA clean beads [3]. |

| Gibson Assembly Master Mix | Enzyme mix for seamless, in vitro assembly of multiple DNA fragments. | Contains exonuclease, polymerase, and ligase. Commercial kits are available. |

| Vector Backbone | Plasmid for harboring the cloned BGC, enabling selection and propagation. | Must be linearized and contain 5' overhangs homologous to the ends of the target BGC fragment. |

| Genomic DNA (gDNA) | Source DNA containing the target BGC. | High-quality, high-molecular-weight gDNA is critical. Isolated via phenol-chloroform extraction [3]. |

| T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit | For high-efficiency synthesis of sgRNAs. | Used according to manufacturer's instructions [3]. |

sgRNA Design and Synthesis

- Design: Identify two target sequences (approximately 20 nucleotides each) that flank the BGC of interest. These targets must be adjacent to a Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM), typically NGG for SpCas9 [14]. Tools from the Zhang Lab (https://www.zlab.bio/Resources-guidedesign) are recommended for design [3].

- Template Preparation: Obtain the double-stranded DNA template for sgRNA transcription via PCR annealing. Use a forward primer containing the T7 promoter sequence followed by the target-specific 20 nt sequence, and a universal reverse primer that binds to the sgRNA scaffold [3].

- Transcription & Purification: Perform in vitro transcription using a commercial T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit. After the reaction, purify the resulting sgRNA using VAHTS RNA Clean Beads or a similar solid-phase reversible immobilization (SPRI) bead-based method to remove unincorporated nucleotides and enzymes [3].

Cas9 Protein Expression and Purification

- Expression: Clone the Cas9 gene into an expression vector like pET28a and transform it into an E. coli expression strain such as BL21(DE3). Induce protein expression with 0.4 mM IPTG when the OD600 reaches 0.6-0.8, and incubate at 16°C for 20 hours [3].

- Purification: Lyse the cells and purify the recombinant Cas9 protein using affinity chromatography (e.g., Ni-NTA for His-tagged Cas9) followed by a polishing step with a system like AKTA pure to ensure high purity and nuclease-free conditions [3].

In Vitro CRISPR Cleavage and Gibson Assembly

- Cleavage Reaction: Set up the CRISPR cleavage reaction by combining the following components and incubating at 37°C for 2 hours:

- Purified genomic DNA (100-500 ng)

- Purified Cas9 protein (e.g., 2 µg)

- sgRNA(s) targeting both flanks (e.g., 1 µg each)

- Appropriate reaction buffer This step will linearize the vector and release the target BGC fragment from the genomic DNA [3].

- Gibson Assembly: Without purifying the cleavage products, directly add a portion of the reaction mixture (e.g., 2 µL) to the Gibson Assembly Master Mix along with the linearized vector backbone. The assembly reaction typically runs for 1 hour at 50°C, seamlessly joining the BGC fragment into the vector via homologous recombination [3].

- Transformation and Verification: Transform the entire assembly reaction into a highly competent E. coli strain. Screen resulting colonies by colony PCR and restriction digestion to identify correct clones. Validate positive clones by Sanger sequencing across the insertion sites.

The following workflow diagram, titled "ICE BGC Cloning Workflow", illustrates the entire protocol from start to finish.

Analysis and Validation of CRISPR Edits

Following the cloning and propagation of the refactored BGC, it is crucial to verify the integrity of the CRISPR-edited construct. The ICE (Inference of CRISPR Edits) analysis tool, developed by Synthego, provides a robust solution for this validation step [27] [28]. This software uses Sanger sequencing data from the cloned construct to deliver quantitative, next-generation sequencing (NGS)-quality analysis, offering a ~100-fold cost reduction compared to full NGS [27] [29].

To use the ICE tool, researchers upload their Sanger sequencing files (.ab1), input the gRNA target sequence(s) used for cloning, and select the nuclease (e.g., SpCas9). The algorithm then compares the edited sample trace to a control trace (if available) and calculates key metrics, summarized in Table 3.

Table 3: Key Output Metrics from ICE Analysis

| Metric | Description | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Indel Percentage | The editing efficiency; percentage of sequences with non-wild type indels [27] [29]. | For BGC cloning, a high percentage may indicate efficient cleavage but imperfect repair, which could be undesirable. A low percentage is ideal for precise cloning. |

| Knock-in Score (KI Score) | The proportion of sequences with the desired, precise knock-in edit [27] [29]. | The primary metric for BGC cloning success. A high KI Score indicates a high percentage of correct assemblies. |

| Model Fit (R²) | Indicates how well the sequencing data fits the predicted model for indel distribution [27] [29]. | A higher R² value (close to 1.0) provides greater confidence in the accuracy of the ICE results. |

| Alignment Visualization | Visual overlay of sequencing traces from edited and control samples [28]. | Allows for manual inspection of the sequencing chromatogram around the cut site to confirm clean, precise editing. |

The logical relationship between the experimental workflow and its subsequent validation is captured in the following analysis diagram, titled "Experiment to Analysis Flow".

The ICE methodology for seamless refactoring of gene clusters establishes a new benchmark for efficiency and accessibility in large DNA fragment cloning. By integrating the precision of CRISPR-Cas9 with the simplicity of Gibson assembly, this protocol enables researchers to directly capture and reassemble BGCs up to 80 kb in under three days with high fidelity [3]. This streamlined workflow, coupled with the powerful and cost-effective ICE analysis tool for validation, provides a complete and robust pipeline from concept to verified clone. For the field of drug development, where accessing and engineering natural product pathways is paramount, the ICE protocol offers a powerful tool to accelerate the discovery and optimization of novel therapeutics. Its application promises to unlock previously inaccessible chemical diversity, paving the way for new treatments for a range of diseases.

The cloning of large DNA fragments, such as those encompassing biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), is a critical but challenging endeavor in synthetic biology and natural product discovery. These fragments, often spanning tens to hundreds of kilobases, have traditionally been difficult to clone using conventional methods due to limitations with restriction sites, low efficiency, and operational complexity [17]. In response to these challenges, a novel method that combines the programmable precision of the CRISPR/Cas9 system with the seamless assembly capability of Gibson assembly has been developed [17]. This platform enables the direct capture and cloning of large genomic fragments ranging from 30 to 77 kb with high fidelity, providing a streamlined and efficient tool for researchers aiming to heterologously express entire gene clusters for functional studies or therapeutic compound production [17] [15]. This protocol details the application of this combined technology within the broader context of CRISPR-Cas9-driven biosynthetic gene cluster cloning research.

Principle of the Method

The core innovation of this method lies in its two-step enzymatic process: CRISPR/Cas9-mediated excision of the target DNA fragment from genomic DNA, followed by in vitro Gibson assembly to ligate the fragment into a vector backbone.

- CRISPR/Cas9 Cleavage: The method utilizes the Cas9 nuclease, complexed with two synthetic single-guide RNAs (sgRNAs) that are designed to flank the target genomic region. This complex introduces precise double-strand breaks at the boundaries of the desired fragment, liberating it from the chromosome in a predetermined and restriction enzyme-free manner [17].

- Gibson Assembly: The linearized vector is prepared using the same sgRNAs to ensure homologous ends. The excised genomic fragment and the prepared vector are then mixed with Gibson assembly master mix, an isothermal single-reaction mixture containing a 5' exonuclease, a DNA polymerase, and a DNA ligase. The exonuclease creates single-stranded 3' overhangs that facilitate the annealing of the fragment and vector via their homologous ends. The polymerase fills in the gaps, and the ligase seals the nicks, resulting in a circular, recombinant plasmid ready for transformation [17].

Table 1: Key Advantages Over Traditional Large-Fragment Cloning Methods

| Method | Principle | Key Limitations | Advantages of CRISPR/Gibson |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transformation-Associated Recombination (TAR) | Homologous recombination in yeast | Difficult plasmid extraction from yeast; complex restriction analysis [17] | Simplified E. coli-based system; straightforward analysis [17] |

| ExoCET | RecET recombination & exonuclease | Dependent on restriction enzymes to release BGCs [17] | Restriction-site independent; uses programmable sgRNAs [17] |

| CATCH | CRISPR/Cas9 cleavage from agarose-embedded DNA | Complex operation due to agarose embedding [17] | Simplified solution-based reaction [17] |

Applications in Biosynthetic Gene Cluster Research

This combined CRISPR/Gibson assembly method is particularly powerful for the study of biosynthetic gene clusters (BGCs), which are co-localized groups of genes responsible for the production of bioactive natural products. Its utility has been demonstrated in practical applications:

- Cloning from Streptomyces: A 40 kb DNA fragment was successfully cloned from Streptomyces ceruleus A3(2), a bacterium renowned for being rich in BGCs for natural products [17].

- Heterologous Expression of Bioactive Compounds: The 40 kb fengycin synthetic gene cluster from B. subtilis 168 was cloned using this method. Fengycins are lipopeptides with potent bioactivity, and this achievement underscores the method's capability to capture functional pathways for heterologous expression and product discovery [17] [15].

The technology provides efficient and simple opportunities for assembling large DNA constructs from diverse organisms, thereby accelerating the exploration of previously inaccessible natural product reservoirs [17].

Materials and Reagents

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 2: Key Reagents and Their Functions in the CRISPR/Gibson Workflow

| Category | Reagent/Kit | Function in the Protocol |

|---|---|---|

| sgRNA Preparation | T7 High Yield RNA Transcription Kit [17] | Generates sgRNA via in vitro transcription. |

| VAHTS RNA Clean Beads [17] | Purifies transcribed sgRNA. | |

| Cas9 Protein | Recombinant Cas9 from S. pyogenes [17] | Nuclease that, complexed with sgRNA, cleaves genomic DNA at target sites. |

| Molecular Cloning | Gibson Assembly Master Mix | Executes the seamless in vitro assembly of the fragment and vector. |

| Host Strain | E. coli BL21(DE3) [17] | Expression host for Cas9 protein production and transformation of recombinant plasmids. |

| General Reagents | Phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol [17] | Purifies genomic DNA and post-CRISPR reaction mixtures. |

| SalI and NcoI Restriction Enzymes [17] | Used for cloning the Cas9 gene into an expression vector (e.g., pET28a). |

Step-by-Step Protocol

sgRNA Design and Synthesis

- Design: Design two 20 bp oligonucleotides complementary to the genomic sequences that immediately flank the target BGC. These protospacers must be adjacent to a 5'-NGG-3' Protospacer Adjacent Motif (PAM) [17] [16]. Resources from the Zhang lab (zlab.bio) can be used for guide design [17].

- Template Preparation: Generate the double-stranded DNA template for sgRNA synthesis by PCR annealing using a universal reverse primer (sgRNA-scaffold-R) and a forward primer containing the T7 promoter and the 20 bp target-specific sequence [17].

- Transcription and Purification: Perform in vitro transcription using a commercial kit (e.g., Vazyme). Purify the resulting sgRNA using RNA Clean Beads [17].

Cas9 Protein Expression and Purification

- Cloning: Clone the Cas9 gene into the pET28a vector using SalI and NcoI restriction sites [17].

- Expression: Transform the constructed plasmid into E. coli BL21(DE3). Grow a 1 L culture and induce protein expression with 0.4 mM IPTG when OD600 reaches 0.6-0.8. Induce at 16°C for 20 hours [17].

- Purification: Purify the recombinant Cas9 protein using a standard affinity chromatography system (e.g., ÄKTA) [17].

Preparation of Genomic DNA

Extract high-quality, high-molecular-weight genomic DNA from the source organism (e.g., Streptomyces, B. subtilis) using a standard phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol extraction protocol. For Gram-positive bacteria, include a lysozyme digestion step [17].

In Vitro Cas9 Cleavage of Genomic DNA

- Pre-complex Cas9 and sgRNAs: In a 300 µL reaction, combine 800 nM Cas9, 400 nM of each sgRNA, 1x NEB Buffer 3.1, and a recombinant ribonuclease inhibitor (RRI). Incubate at 37°C for 20 minutes [17].

- Initiate Cleavage: Add 0.02-0.04 nM genomic DNA to the pre-formed complex. Incubate at 37°C for 2 hours [17].

Purification of Cleaved DNA Fragment

- Add an equal volume (300 µL) of phenol-chloroform-isoamyl alcohol (pH 8.0) to the cleavage reaction. Centrifuge and collect the aqueous supernatant [17].

- To 200 µL of the supernatant, add 20 µL of 3 M sodium acetate and 1.2 mL of anhydrous ethanol to precipitate the DNA. Wash the pellet with 75% ethanol, air-dry, and resuspend in 100 µL of ddH2O [17].

Vector Preparation and Gibson Assembly

- Vector Linearization: Prepare the receiving vector by digesting it with Cas9 complexed with the same sgRNAs used for genomic DNA cleavage, ensuring homologous ends for Gibson assembly.

- Assembly Reaction: Mix the purified target DNA fragment and the linearized vector in a 1:1 molar ratio with Gibson assembly master mix. Incubate at 50°C for 15-60 minutes.

- Transformation and Screening: Transform the assembly reaction into competent E. coli. Screen resulting colonies by colony PCR and/or restriction digestion to identify positive clones. Validate final constructs by Sanger sequencing across the assembly junctions [17].

Performance and Validation

The method's performance has been quantitatively assessed for fragments of various sizes, demonstrating its robustness for large-scale cloning projects.

Table 3: Quantitative Cloning Performance of the CRISPR/Gibson Method

| Size of DNA Fragment | Cloning Efficiency | Cloning Fidelity | Demonstrated Example |

|---|---|---|---|

| 15 kb | High | Not specified | Standard fragment [17] |

| 30 kb | Successful cloning | Near 100% (<50 kb) [17] | Standard fragment [17] |

| 40 kb | Successful cloning | Near 100% (<50 kb) [17] | Fengycin cluster from B. subtilis [17] |

| 50 kb | Successful cloning | Near 100% (<50 kb) [17] | Standard fragment [17] |

| 60 kb | Successful cloning | Fidelity decreases for >50 kb [17] | Standard fragment [17] |

| 77 kb | Successful cloning (max reported) | Fidelity decreases for >50 kb [17] | Standard fragment [17] |

| 100 kb | Not successfully cloned | Not applicable | Target size attempted [17] |

Workflow and Mechanism

The following diagram summarizes the experimental workflow, from sgRNA design to the final recombinant clone.

Troubleshooting

- Low Cleavage Efficiency: Ensure sgRNAs are highly specific and active by testing them in vitro before use. Verify the purity and concentration of both Cas9 protein and sgRNAs.

- Poor Assembly/Transformation Efficiency: Optimize the molar ratio of insert to vector in the Gibson assembly reaction (typically 2:1). Ensure the purified DNA fragment is intact and free of contaminants like salts or phenol.

- High Background (Empty Vector): Increase the efficiency of genomic DNA cleavage to maximize the concentration of the correct insert. Use a vector with a negative selection marker (e.g., ccdB) to counter-select against non-recombinant vectors [30].

In Vivo BGC Capture Using Engineered Cas9 Systems

Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) contain sets of co-localized genes that encode pathways for synthesizing specialized metabolites, many of which form the basis of clinically valuable compounds including antibiotics, anticancer agents, and immunosuppressants [31]. The cloning and heterologous expression of these BGCs represent a powerful strategy for natural product discovery and engineering. However, efficient capture of large BGCs, particularly from organisms with high GC-content genomes like Streptomyces, has remained technically challenging [31] [15].

The CRISPR-Cas9 system has emerged as a precision tool for genome manipulation, but its application for BGC capture in complex genomes has been limited by significant obstacles. Wild-type Cas9 from Streptococcus pyogenes (SpCas9) exhibits substantial off-target cytotoxicity in high GC-content genomes due to frequent occurrence of its NGG protospacer adjacent motif (PAM) sequences, leading to unintended cleavage and cell death [31]. Additionally, conventional in vitro cloning methods face limitations in efficiently capturing large BGC fragments exceeding 50 kb [15].

This Application Note presents innovative solutions to these challenges through engineered Cas9 systems and corresponding methodological advances. We detail the development and application of modified Cas9 variants with reduced off-target effects, describe robust protocols for in vivo BGC capture, and provide practical tools for implementation in high GC-content actinomycetes.

Engineered Cas9 Systems for BGC Capture

Cas9-BD: A Modified Cas9 with Reduced Off-Target Effects

To address the critical limitation of off-target cytotoxicity in high GC-content genomes, researchers have developed Cas9-BD, a strategically engineered Cas9 variant created by adding polyaspartate tags (DDDDD) to both the N- and C-termini of the wild-type SpCas9 protein using flexible glycine-serine linkers [31].

The mechanistic rationale behind this modification lies in the charge-charge interaction between Cas9 and DNA. The native Cas9 protein contains numerous basic residues that interact with the phosphate backbone of target DNA. The addition of negatively charged polyaspartate tags interferes with these interactions specifically at off-target sites, where Cas9 binding affinity is naturally weaker, while maintaining strong binding to on-target sequences [31].

Experimental validation through circular dichroism spectroscopy confirmed that the polyaspartate modification does not disrupt the secondary structural conformation of Cas9 or its ability to bind sgRNA [31]. Importantly, in vitro cleavage assays demonstrated that while Cas9-BD maintains approximately 80% of the on-target cleavage efficiency of wild-type Cas9, it shows dramatically reduced cleavage at off-target sites, particularly those with non-PAM sequences containing -NGA or -NGT [31].

In vivo performance assessment in Streptomyces coelicolor M1146 revealed that Cas9-BD expression under the strong rpsL promoter resulted in significantly less cytotoxicity and improved colony formation compared to wild-type Cas9, confirming reduced off-target activity in high GC-content genomic contexts [31].

Alternative Cas9 Variants and Orthologs

While Cas9-BD represents a significant advancement for BGC capture in actinomycetes, other Cas variants offer complementary capabilities:

Cas12a (Cpf1): This type V effector recognizes T-rich PAM sequences (e.g., "TTTV") and generates staggered ends distal to the recognition site [32]. Its different PAM requirement provides an advantage for targeting genomic regions where NGG PAMs are suboptimally positioned. However, the T-rich PAM recognition limits its application in high GC-content genomes where such sequences are less frequent [31].

Cas12b: A dual-RNA-guided nuclease with a compact size suitable for viral delivery, Cas12b recognizes relatively simple PAM sequences and represents a promising alternative for certain applications [32].

Table 1: Comparison of Engineered Cas Systems for BGC Capture

| System | PAM Requirement | Key Advantages | Limitations | Ideal Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cas9-BD | NGG | Reduced off-target cleavage in high GC genomes; Maintains high on-target efficiency | Still requires NGG PAM sites | BGC capture from Streptomyces and other high GC-content actinomycetes |

| Wild-type SpCas9 | NGG | Well-characterized; Extensive toolkit available | High cytotoxicity in high GC genomes | General use in low GC-content organisms |