Continuous vs Discrete Molecular Optimization: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

This article provides a comparative analysis of continuous and discrete molecular optimization paradigms, crucial for enhancing drug properties in lead compound development.

Continuous vs Discrete Molecular Optimization: A Comprehensive Guide for Drug Discovery

Abstract

This article provides a comparative analysis of continuous and discrete molecular optimization paradigms, crucial for enhancing drug properties in lead compound development. Tailored for researchers and drug development professionals, it explores the foundational principles, core methodologies, and practical applications of each approach. The content addresses common optimization challenges, including synthesizability and multi-objective trade-offs, and evaluates performance through validation metrics and real-world case studies. By synthesizing insights from recent advances, this guide aims to inform strategic decision-making in computational drug discovery.

Defining the Battlefield: Core Principles of Discrete and Continuous Optimization in Chemistry

Molecular optimization is a critical stage in the drug discovery pipeline, focused on the structural refinement of lead molecules to enhance their properties while maintaining the core scaffold responsible for biological activity. The fundamental goal is to generate a molecule y from a lead molecule x, such that its properties p1(y),…,pm(y) are superior to the original, while the structural similarity between x and y remains above a defined threshold [1]. This process aims to address liabilities such as inadequate potency, solubility, or metabolic stability, thereby increasing the likelihood of success in subsequent preclinical and clinical evaluations [1] [2]. The field is characterized by two dominant computational paradigms: optimization in discrete chemical spaces and optimization in continuous latent spaces, each with distinct methodologies, strengths, and challenges [1] [2].

Core Concepts and Definitions

Formal Definition and Objectives The molecular optimization problem is mathematically formulated to find a target molecule (y) from a lead molecule (x) that satisfies two primary conditions:

- Property Enhancement: The target molecule must have improved properties, expressed as pi(y) ≻ pi(x) for i=1,2,…,m. These properties can include biological activity, physicochemical profiles (e.g., LogP, solubility), and pharmacokinetic properties (e.g., metabolic clearance) [1].

- Structural Similarity Constraint: The structural similarity between the original and optimized molecule,

sim(x, y), must be greater than a threshold δ. This ensures the retention of the core scaffold and its essential bioactivity. A frequently used metric is the Tanimoto similarity of Morgan fingerprints [1].

The Critical Role of Scaffold Hopping A key application of molecular optimization is scaffold hopping, a strategy aimed at discovering new core structures (backbones) while retaining similar biological activity [3]. This is crucial for improving drug-like properties, overcoming patent limitations, and exploring novel chemical entities that may have enhanced efficacy and safety profiles [3]. The ability of a molecular representation to facilitate the identification of these structurally diverse yet functionally similar compounds is a critical measure of its effectiveness [3].

Comparative Analysis: Discrete vs. Continuous Optimization Paradigms

The following table summarizes the core characteristics of the two main optimization paradigms, highlighting their fundamental differences in approach, methodology, and typical applications.

Table 1: Core Characteristics of Discrete and Continuous Molecular Optimization Paradigms

| Feature | Optimization in Discrete Chemical Space | Optimization in Continuous Latent Space |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Direct structural modification of molecular representations [1] | Manipulation of continuous vector encodings of molecules [1] [2] |

| Molecular Representation | SMILES, SELFIES strings, or Molecular Graphs (nodes/edges) [1] [4] | Continuous latent vectors (z) from models like VAEs [1] [2] [5] |

| Primary Methods | Genetic Algorithms (GAs), Reinforcement Learning (RL) [1] [2] | Gradient Ascent, Latent Reinforcement Learning (e.g., MOLRL) [1] [2] |

| Key Advantage | Intuitive, direct structural control; can be highly sample-efficient in some cases (e.g., STONED) [1] | Enables use of powerful continuous optimization algorithms; can navigate space more smoothly [2] |

| Key Challenge | Can violate chemical rules, requiring corrective heuristics; high-dimensional search space [2] | No guarantee that a point in latent space decodes to a valid molecule [2] |

Experimental Protocols and Performance Data

To objectively compare the performance of different molecular optimization methods, researchers use standardized benchmark tasks. A widely adopted benchmark involves optimizing the penalized LogP (pLogP) of a set of molecules while maintaining a structural similarity above 0.4 to the original molecules [1] [2]. The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of various state-of-the-art methods on this task, demonstrating the evolution and current capabilities of different approaches.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Molecular Optimization Methods on the pLogP Optimization Benchmark (Similarity > 0.4)

| Model | Optimization Paradigm | Key Methodology | Reported pLogP Improvement (Avg.) | Key Strengths / Notes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JT-VAE [6] | Continuous Latent Space | Gradient ascent on VAE latent space [6] | +2.47 (reported in MOLRL) [2] | Early influential method using graph-based VAE |

| MolDQN [6] | Discrete Chemical Space | Deep Q-Networks & RL on molecular graphs [1] [6] | +2.49 (reported in MOLRL) [2] | Operates directly on molecular graph |

| MOLRL (VAE-CYC) [2] | Continuous Latent Space | Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) on VAE latent space [2] | +3.41 | Demonstrates power of combining latent space with advanced RL |

| MOLRL (MolMIM) [2] | Continuous Latent Space | PPO on mutual information model's latent space [2] | +4.87 | State-of-the-art performance on this benchmark |

| TransDLM [6] | Hybrid (Text-Guided) | Transformer-based Diffusion Language Model [6] | N/A (Excels in multi-property ADMET optimization) [6] | Uses chemical nomenclature, avoids external predictors, reduces error propagation |

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Latent Space Reinforcement Learning (MOLRL)

The MOLRL framework exemplifies a modern, high-performance approach to continuous space optimization [2]. Its experimental protocol can be detailed as follows:

- Generative Model Pre-training: A generative model (e.g., a Variational Autoencoder with cyclical annealing, VAE-CYC, or a MolMIM model) is pre-trained on a large dataset of drug-like molecules (e.g., from the ZINC database). The model learns to encode molecules into a continuous latent vector (z) and decode them back to valid molecular structures (e.g., SMILES) [2].

- Latent Space Evaluation: The quality of the pre-trained model's latent space is critically assessed before optimization. Key metrics include:

- Reconstruction Rate: The average Tanimoto similarity between original molecules and their reconstructions from the latent space (e.g., >0.7 for VAE-CYC) [2].

- Validity Rate: The percentage of randomly sampled latent vectors that decode to syntactically valid molecules (e.g., >85% for VAE-CYC) [2].

- Continuity: The effect of small perturbations in the latent vector on the structural similarity of the decoded molecule, ensuring a smooth and navigable space [2].

- Reinforcement Learning Agent Setup: A Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) agent is initialized to act in the pre-trained latent space. The state (s) is the current latent vector, and the action (a) is a step in the latent space, modifying the vector.

- Optimization Loop: For a given starting molecule (encoded as z0), the RL agent iteratively takes steps.

- Action Execution: The agent proposes a new latent vector, z' = z + Δz.

- Decoding and Evaluation: The new vector z' is decoded into a molecule, and its properties (e.g., pLogP) and similarity to the original molecule are calculated.

- Reward Calculation: A reward is computed based on the improvement in the target property, often subject to the similarity constraint.

- Policy Update: The agent's policy (its strategy for navigating the space) is updated based on the received reward, guiding it towards regions of the latent space that decode to molecules with higher desired properties [2].

Detailed Experimental Protocol: Text-Guided Multi-Property Optimization (TransDLM)

The TransDLM model represents a novel approach that leverages textual descriptions to guide optimization [6].

- Semantic Representation: Instead of using SMILES strings directly, the model converts molecules into standardized chemical nomenclature (e.g., IUPAC names) to create a more semantically rich representation [6].

- Model Architecture: A transformer-based diffusion language model is trained. Diffusion models learn to generate data by iteratively denoising random noise [6].

- Conditioning and Guidance: The desired property requirements are implicitly embedded into textual descriptions (e.g., "high solubility," "low clearance"). This text, along with the source molecule's semantic representation, guides the diffusion denoising process. This method, known as Molecular Context Guidance (MCG), directly incorporates property goals without relying on error-prone external predictors [6].

- Sampling and Optimization: The optimization process starts from the token embeddings of the source molecule, ensuring the core scaffold is retained. The diffusion model then iteratively denoises this representation, steered by the text guidance, to produce an optimized molecule that fulfills the multi-property requirements [6].

Essential Research Toolkit for Molecular Optimization

A modern research workflow in molecular optimization relies on a combination of software libraries, computational tools, and chemical databases.

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Molecular Optimization

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [2] | Software Library | Cheminformatics toolkit; used for parsing SMILES, calculating molecular descriptors, fingerprints, and similarity metrics (e.g., Tanimoto) [2]. |

| ZINC Database [2] [5] | Chemical Library | A publicly available database of commercially available compounds; used for pre-training generative models and as a source of initial lead molecules [2] [5]. |

| AutoDock Vina / SwissADME [7] | Computational Predictor | Used for virtual screening and predicting binding affinity (docking) or drug-likeness/ADMET properties, often serving as an oracle in guided searches [7]. |

| VAE / MolMIM Models [2] | Generative Model | Architectures used to create a continuous latent space for molecules, which serves as the environment for continuous optimization algorithms like MOLRL [2]. |

| GenMol [8] | Generative Framework | A generalist model using discrete diffusion; unified framework for tasks like de novo generation and lead optimization via its "fragment remasking" strategy [8]. |

| CETSA [7] | Experimental Assay | Cellular Thermal Shift Assay; used for experimental validation of target engagement in physiologically relevant environments after in silico optimization [7]. |

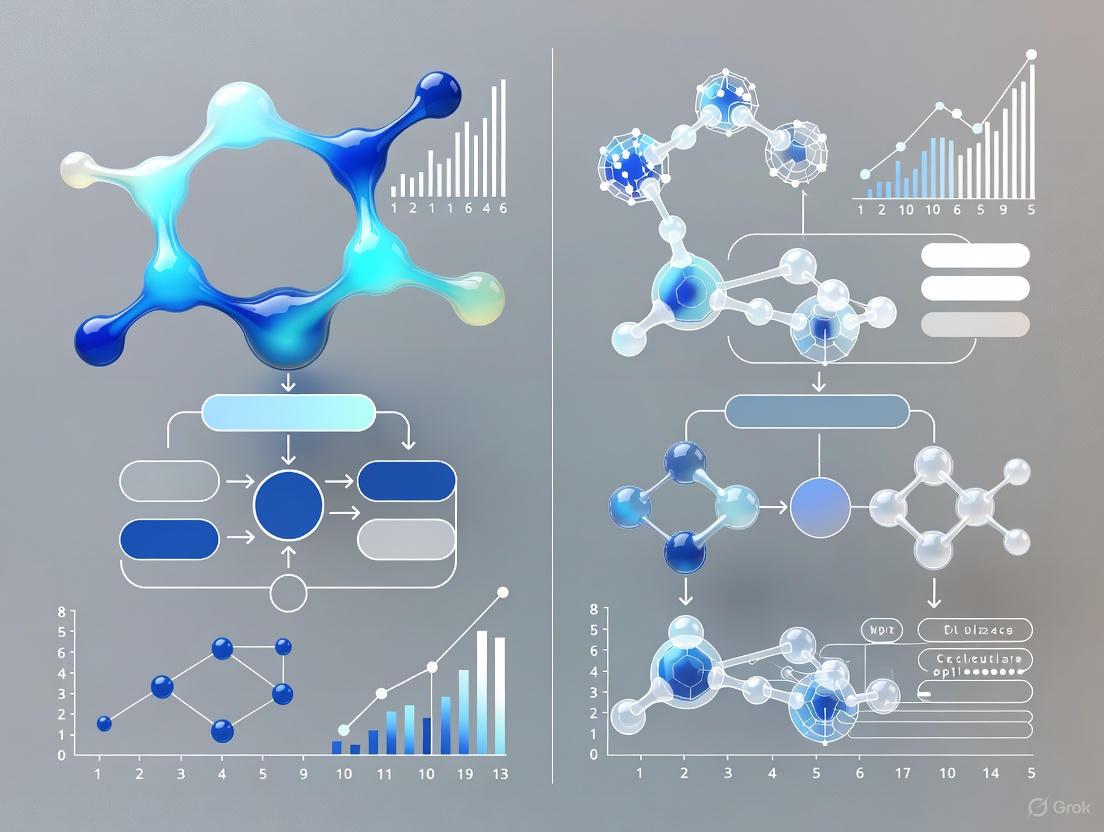

Visualizing Optimization Workflows and Relationships

The following diagrams illustrate the logical structure of the two primary optimization paradigms and a specific advanced implementation, highlighting the key steps and decision points.

Diagram 1: Discrete Space Optimization Logic. This workflow involves direct, iterative structural modification and evaluation of molecules in their native discrete format (e.g., as graphs or strings).

Diagram 2: Continuous Space Optimization Logic. This workflow maps a molecule to a continuous vector, performs optimization in that space, and then decodes the improved vector back into a molecular structure.

Diagram 3: Active Learning GM Workflow. This integrated workflow (e.g., from VAE-AL) combines generative AI with iterative, oracle-driven feedback to simultaneously explore novelty and optimize for target engagement and synthesizability [5].

In the realm of computational molecular research, optimization methodologies are broadly divided into two paradigms: continuous and discrete. Discrete optimization is a branch of applied mathematics and computer science that deals with problems where decision variables are restricted to a countable set of values, such as integers, graphs, or molecular descriptors like SMILES strings [9]. This stands in direct contrast to continuous optimization, where variables can assume any real value within a given interval.

The distinction is not merely academic; it is fundamental to how researchers navigate the complex landscape of molecular design. While continuous optimization operates in smooth, differentiable parameter spaces, discrete optimization tackles problems where solutions are distinct, separate entities. In pharmaceutical research, this translates to working with whole molecules, specific atomic arrangements, and distinct structural motifs rather than continuous chemical gradients [10].

This article examines discrete optimization's pivotal role in molecular research, comparing its approaches and performance against continuous methods. We provide experimental data, detailed methodologies, and essential toolkits to guide researchers in selecting appropriate strategies for drug discovery and development challenges.

Theoretical Foundations: Key Concepts and Variables

The Landscape of Discrete Optimization

Discrete optimization encompasses several interconnected branches. Combinatorial optimization focuses on problems involving discrete structures like graphs and matroids, which are essential for representing molecular connectivity and similarity [9]. Integer programming extends linear programming to require solutions to take integer values, crucial when modeling countable entities like atoms or molecules. Constraint programming solves problems by stating constraints between variables, well-suited for ensuring chemical validity in molecular design [9].

At the heart of molecular discrete optimization lies the challenge of navigating complex potential energy surfaces (PES). These multidimensional hypersurfaces map a molecular system's potential energy as a function of its nuclear coordinates [10]. Each point represents a specific molecular geometry, with local minima corresponding to stable structures and saddle points indicating transition states. The exponential growth in local minima with increasing system size makes locating the global minimum (GM)—the most thermodynamically stable structure—particularly challenging [10].

Discrete Variables in Molecular Optimization

Molecular optimization employs three principal types of discrete variables:

- Integers: Used to represent countable quantities such as atom counts, ring sizes, bond orders, and the number of specific functional groups in a molecule [11].

- Graphs: Molecular structures naturally map to graph representations where atoms serve as nodes and bonds as edges, enabling the application of graph theory to chemical problems [9].

- SMILES Strings: The Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System provides a string-based representation of molecular structure, offering a discrete sequence representation that is particularly amenable to natural language processing techniques [12].

Methodological Approaches: A Comparative Analysis

Stochastic versus Deterministic Strategies

Global optimization methods for molecular structure prediction are typically categorized into stochastic and deterministic approaches, each with distinct exploration strategies and theoretical foundations [10].

Table 1: Classification of Global Optimization Methods

| Category | Representative Methods | Key Characteristics | Molecular Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Stochastic | Genetic Algorithms, Simulated Annealing, Particle Swarm Optimization | Incorporate randomness in structure generation/evaluation; avoid premature convergence | Exploring complex, high-dimensional energy landscapes; flexible molecular systems |

| Deterministic | Molecular Dynamics, Single-Ended Methods, Basin Hopping | Follow defined rules without randomness; use analytical information (gradients) | Precise convergence for smaller systems; sequential evaluation of candidates |

Stochastic methods incorporate randomness in generating and evaluating structures, typically beginning with random or probabilistically guided perturbations followed by local optimization to identify nearby minima [10]. Their non-deterministic nature enables broad sampling of complex, high-dimensional energy landscapes. In contrast, deterministic methods rely on analytical information such as energy gradients or second derivatives to direct searches toward low-energy configurations [10]. These approaches follow defined trajectories based on physical principles but can become computationally expensive for systems with numerous local minima.

AI-Driven Discrete Molecular Optimization

Artificial intelligence has revolutionized discrete molecular optimization through several transformative approaches:

Molecular Language Models leverage SMILES strings as discrete sequences, adapting natural language processing techniques to molecular design. The MLM-FG framework exemplifies this approach with a novel pre-training strategy that randomly masks subsequences corresponding to chemically significant functional groups [12]. This forces the model to learn the context of these key structural units, improving its ability to infer molecular properties.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) operate directly on the discrete graph representation of molecules, capturing topological relationships between atoms and bonds [12]. Recent extensions incorporate 3D structural information to enhance model performance, though this requires accurate conformational data that can be computationally expensive to obtain [12].

Reinforcement Learning formulates molecular optimization as a Markov decision process where agents iteratively refine policies to generate molecules with desired properties through reward-driven strategies [13].

Experimental Comparison: Performance Benchmarks

Molecular Property Prediction Performance

Extensive evaluations benchmark the performance of discrete optimization approaches against continuous and hybrid methods across standard molecular property prediction tasks. The following table summarizes results from comprehensive studies comparing SMILES-based, graph-based, and 3D-structure-aware models:

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Molecular Optimization Models on Benchmark Tasks

| Model Type | Representative Models | BBBP | ClinTox | Tox21 | HIV | Average Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES-Based (Discrete) | MLM-FG | 0.947 | 0.942 | 0.854 | 0.839 | Outperforms in 9/11 tasks |

| 2D Graph-Based | MolCLR, GROVER | 0.901 | 0.913 | 0.826 | 0.804 | Competitive on structural splits |

| 3D Graph-Based | GEM | 0.928 | 0.931 | 0.841 | 0.822 | Enhanced but computationally intensive |

| Continuous Optimization | Traditional QSAR | 0.872 | 0.854 | 0.791 | 0.763 | Lower on generalization tasks |

Notably, the discrete SMILES-based approach MLM-FG outperformed existing pre-training models—both SMILES- and graph-based—in 9 out of 11 downstream tasks in rigorous evaluations, ranking as a close second in the remaining tasks [12]. Remarkably, MLM-FG even surpassed some 3D-graph-based models that explicitly incorporate molecular structures into their inputs, highlighting its exceptional capacity for representation learning without explicit 3D structural information [12].

Optimization Efficiency in Drug Discovery

In practical drug discovery applications, discrete optimization approaches have demonstrated significant acceleration of development timelines while reducing costs:

Table 3: Optimization Efficiency in AI-Driven Drug Discovery

| Metric | Traditional Methods | AI-Driven Discrete Optimization | Exemplary Compounds |

|---|---|---|---|

| Development Timeline | 10-15 years | Significantly reduced (2-5 years for some candidates) | INS018-055 (Phase 2a) [13] |

| Cumulative Expenditure | Exceeding $2.5 billion | Substantially reduced | RLY-4008 (Phase 1/2) [13] |

| Clinical Trial Success Rate | 8.1% overall | Improved through better candidate selection | ISM-3091 (Phase 1) [13] |

The transformative potential of these approaches is evidenced by multiple AI-discovered molecules progressing through clinical trials, such as Insilico Medicine's INS018-055 for idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, which reached Phase II trials in approximately one-third the traditional time [13] [14].

Experimental Protocols: Methodologies for Discrete Molecular Optimization

Protocol 1: MLM-FG Pre-training and Fine-tuning

The MLM-FG methodology employs a structured approach to molecular representation learning:

Step 1: Data Collection and Preparation

- Obtain large-scale molecular datasets from public repositories like PubChem [12].

- Standardize molecular representations using canonical SMILES strings.

- Identify and annotate functional groups within each molecular structure using cheminformatics tools like RDKit.

Step 2: Functional Group-Aware Masking

- Parse SMILES strings to identify subsequences corresponding to chemically significant functional groups [12].

- Randomly mask a proportion (typically 15-20%) of these functional group subsequences rather than random token masking.

- Preserve the standard SMILES syntax while applying masking to maintain compatibility with existing toolkits.

Step 3: Model Pre-training

- Employ transformer-based architectures (MoLFormer or RoBERTa) as backbone models [12].

- Train models to reconstruct masked functional groups based on contextual information in the SMILES string.

- Use self-supervised objectives that maximize the model's ability to infer chemically meaningful substructures.

Step 4: Downstream Task Fine-tuning

- Adapt pre-trained models to specific molecular property prediction tasks through transfer learning.

- Use task-specific datasets with appropriate train/validation/test splits, preferably using scaffold splitting to assess generalization capability [12].

- Fine-tune all model parameters rather than using fixed embeddings to maximize task performance.

Protocol 2: Global Optimization of Molecular Structures

For predicting stable molecular conformations and crystal structures, a typical global optimization workflow involves:

Step 1: Initial Structure Generation

- Create diverse starting configurations using random sampling, template-based generation, or fragment assembly [10].

- Ensure adequate structural diversity to facilitate broad exploration of the potential energy surface.

Step 2: Combined Global-Local Optimization

- Implement a hybrid approach where global exploration is interleaved with local refinement [10].

- Apply stochastic methods (e.g., genetic algorithms, simulated annealing) to escape local minima.

- Use efficient local optimization algorithms (e.g., gradient-based methods) to refine candidate structures to the nearest local minimum.

Step 3: Energy Evaluation and Selection

- Employ first-principles computational methods such as Density Functional Theory (DFT) for accurate energy calculations [10].

- Use force field methods for preliminary screening to reduce computational cost for large systems.

- Maintain a diverse set of low-energy candidates to avoid premature convergence.

Step 4: Redundancy Removal and Validation

- Identify and remove duplicate or symmetrically equivalent structures [10].

- Perform frequency calculations to confirm that optimized structures represent true minima (no imaginary frequencies).

- Select the lowest-energy structure as the putative global minimum for further analysis.

Global Optimization Workflow: This diagram illustrates the iterative process of molecular global optimization, combining stochastic and deterministic approaches.

Table 4: Essential Resources for Discrete Molecular Optimization Research

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Platforms | Function/Purpose |

|---|---|---|

| Cheminformatics Toolkits | RDKit, OpenBabel | Process molecular representations, identify functional groups, calculate descriptors |

| Quantum Chemistry Software | Gaussian, ORCA, DFTB+ | Perform accurate energy calculations for molecular structures |

| Optimization Frameworks | Gurobi, SCIP, GRRM | Solve discrete optimization problems with various algorithmic approaches |

| Deep Learning Frameworks | PyTorch, TensorFlow, DeepChem | Implement and train molecular machine learning models |

| Molecular Datasets | PubChem, ZINC, ChEMBL, MoleculeNet | Provide labeled data for training and benchmarking models |

| Specialized Molecular Models | MLM-FG, MoLFormer, GEM | Pre-trained models for molecular property prediction |

The comparison between discrete and continuous optimization approaches in molecular research reveals a complex landscape where each paradigm offers distinct advantages. Discrete optimization provides the necessary framework for navigating the inherently countable nature of molecular entities—whole molecules, specific atomic arrangements, and distinct structural motifs. The experimental evidence demonstrates that discrete approaches, particularly AI-driven methods like MLM-FG, achieve state-of-the-art performance across diverse molecular property prediction tasks while offering computational efficiency advantages over structure-aware continuous methods [12].

The strategic integration of both discrete and continuous approaches presents the most promising path forward. Hybrid methodologies that leverage discrete optimization for molecular scaffold generation and continuous optimization for fine-grained property refinement may offer optimal balance between exploration and exploitation in chemical space. As artificial intelligence continues to transform pharmaceutical research [13] [15] [14], discrete optimization will remain foundational for addressing the countable nature of molecular design choices, while continuous methods will maintain their role in optimizing within those discrete choices. This synergistic relationship will ultimately accelerate the discovery of novel therapeutics and advance computational molecular design.

The exploration of chemical space for drug discovery is fundamentally constrained by its vastness, making exhaustive manual or computational evaluation an impossible endeavor [16]. Generative deep learning models have emerged as a powerful solution to this challenge, proposing candidate molecules by learning underlying data distributions. However, the critical secondary step—optimizing these generated molecules for specific, desired properties—has spawned two distinct research philosophies: one operating in discrete spaces (directly manipulating molecular structures) and the other in continuous, differentiable latent spaces. This guide provides a objective comparison of these paradigms, with a focused examination of the tools, protocols, and performance metrics for continuous optimization via latent spaces.

This continuous approach involves searching through a compressed, real-valued representation—the latent space—of a pre-trained generative model. The core advantage is the conversion of a complex discrete optimization problem (e.g., modifying molecular graphs) into a more tractable continuous one, enabling the use of powerful gradient-based and black-box optimization algorithms [2]. We demystify this process by presenting experimental data, detailed methodologies, and the essential toolkit required for its implementation.

Experimental Comparison: Continuous vs. Discrete Optimization

The following table summarizes the performance of various continuous and discrete optimization methods on common molecular optimization benchmarks.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Molecular Optimization Methods

| Method | Optimization Space | Core Approach | pLogP Optimization (↑) | Success Rate (Scaffold Constraint) | Validity Rate (↑) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MOLRL (PPO) [2] | Continuous (Latent) | Reinforcement Learning (Proximal Policy Optimization) | ~2.9 | 84% | >99% |

| Multi-Objective LSO [17] | Continuous (Latent) | Iterative Weighted Retraining (Pareto Efficiency) | N/A - Multi-property | N/A | Data Not Provided |

| Surrogate Latents [18] | Continuous (Latent) | Black-box Optimisation (BO, CMA-ES) | Benchmarking Successful | Demonstrated for Proteins | High (Architecture Agnostic) |

| JAM [2] | Discrete (Graph) | Reinforcement Learning & Monte Carlo Tree Search | ~2.7 | 60% | Data Not Provided |

| Graph GA [2] | Discrete (Graph) | Genetic Algorithm | ~1.9 | 50% | Data Not Provided |

| GFL [2] | Discrete (Graph) | Supervised Learning (Best-of-N Fine-Tuning) | ~2.5 | 70% | Data Not Provided |

Note: pLogP (penalized LogP) is a benchmark for optimizing molecular hydrophobicity while penalizing unrealistic structures. A higher value is better. "N/A" indicates the property was not the focus of the reported experiment.

Key Insights from Comparative Data

- Efficacy in Constrained Optimization: Continuous methods, particularly MOLRL, demonstrate superior performance in scaffold-constrained optimization, achieving an 84% success rate compared to 60-70% for discrete methods [2]. This indicates a stronger capability to navigate towards specific molecular sub-regions.

- High Validity and Smoothness: Models like VAE with cyclical annealing and MolMIM report validity rates >99% and demonstrate smooth latent spaces, where small perturbations lead to structurally similar molecules [2]. This continuity is crucial for the stability and efficiency of continuous optimization algorithms.

- Multi-Objective Optimization: Continuous spaces naturally facilitate multi-objective optimization. The Multi-Objective LSO method uses Pareto efficiency to effectively bias generative models toward molecules with an optimal balance of multiple properties [17].

Experimental Protocols for Latent Space Optimization

Protocol 1: Single-Property Optimization with Reinforcement Learning

This protocol is based on the MOLRL framework for optimizing a single property, such as pLogP [2].

- Model Pre-training: A generative autoencoder (e.g., VAE or MolMIM) is pre-trained on a large molecular dataset (e.g., ZINC). The model must be validated for high reconstruction accuracy and latent space continuity [2].

- Latent Space Evaluation: The latent space is evaluated for smoothness by perturbing latent vectors with Gaussian noise (variances of σ=0.1, 0.25, 0.5) and measuring the average Tanimoto similarity between original and perturbed molecules. A smooth decline in similarity indicates a continuous space [2].

- RL Agent Training: A Reinforcement Learning agent (e.g., using Proximal Policy Optimization - PPO) is trained. The state is the current latent vector, the action is a step in the latent space, and the reward is the property score (e.g., pLogP) of the molecule decoded from the new latent vector.

- Constrained Optimization: For scaffold constraints, the reward function is modified to include a penalty for dissimilarity to the target scaffold.

- Validation: The top-performing molecules proposed by the agent are synthesized and validated experimentally in vitro.

Protocol 2: Multi-Objective Optimization via Iterative Retraining

This protocol outlines the weighted retraining approach for balancing multiple molecular properties [17].

- Initial Batch Generation: An initial set of molecules is generated from the pre-trained model.

- Property Evaluation & Pareto Ranking: All molecules are evaluated for the multiple target properties (e.g., biological activity, solubility). Each molecule is then ranked based on its Pareto efficiency, indicating how non-dominated it is across all objectives.

- Dataset Weighting: The data for the next training cycle is re-weighted, giving higher importance to molecules with better Pareto ranks.

- Model Retraining: The generative model is retrained on this weighted dataset, biasing its latent space towards regions that produce high-performing, Pareto-optimal molecules.

- Iteration: Steps 2-4 are repeated for several cycles, progressively pushing the model to generate improved candidates.

Workflow Visualization

The following diagram illustrates the logical relationship and workflow for the two primary continuous optimization protocols described above.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item / Resource | Function in Latent Space Optimization | Example / Note |

|---|---|---|

| Generative Model Architectures | Creates the differentiable latent space for optimization. | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) with cyclical annealing [2], MolMIM [2], or other autoencoders [16]. |

| Optimization Algorithms | Navigates the latent space to find regions with desired properties. | Proximal Policy Optimization (PPO) [2], Bayesian Optimisation (BO), CMA-ES [18]. |

| Molecular Datasets | Provides data for pre-training generative models. | ZINC database [2], MOSES benchmarking dataset [16]. |

| Chemical Evaluation Toolkits | Calculates physicochemical properties and validates molecular structures. | RDKit software for validity checks and similarity metrics (e.g., Tanimoto) [2]. |

| Property Prediction Models | Provides the objective function for optimization; can be quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models. | Pre-trained models for properties like pLogP, drug-likeness, or target binding affinity [2]. |

| Architecture Engineering | Optimizes model performance and resource efficiency for molecular data. | Systematic analysis of latent size, hidden layers, and attention mechanisms [16]. |

The empirical data and methodologies presented herein demonstrate that continuous optimization in differentiable latent spaces offers a powerful and versatile framework for targeted molecular generation. Key advantages include superior performance in complex, constrained tasks and a natural facility for multi-objective optimization. The choice between continuous and discrete paradigms is not merely technical but strategic; continuous optimization excels in sample efficiency and navigating complex property landscapes, while discrete methods offer more direct structural control. As generative models continue to evolve, producing richer and more structured latent spaces, the ability to efficiently navigate them using the continuous optimization techniques demystified in this guide will be paramount for accelerating drug discovery and materials science.

Molecular optimization, a critical process in drug discovery and materials science, revolves around a central challenge: navigating the vast chemical space to identify compounds with an optimal balance of multiple properties. This field encompasses two fundamentally different approaches to representing and manipulating molecular structures—discrete and continuous formulations—each with distinct advantages and limitations. Discrete methods treat molecules as categorical entities, operating on specific atoms, bonds, or fragments, while continuous approaches represent molecules in smooth, interpolatable latent spaces, enabling gradient-based optimization techniques. The choice between these paradigms significantly influences how variables are handled, how the chemical space is explored, and ultimately, the effectiveness of the optimization process. This guide provides an objective comparison of prominent molecular optimization strategies, examining their performance, experimental protocols, and suitability for different research scenarios within the broader context of discrete versus continuous research frameworks.

Comparative Analysis of Optimization Approaches

The following table summarizes the core characteristics, performance data, and key differentiators of major molecular optimization methods.

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Molecular Optimization Methods

| Method (Representation) | Optimization Approach | Key Performance Metrics | Variable Handling | Primary Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| GARGOYLES (Graph) [19] | Deep Reinforcement Learning (MCTS) | QED: 0.928; Similarity: High; Validity: 100% [19] | Discrete graph edits (atom/fragment) | High similarity to starting compound; always valid molecules |

| SIB-SOMO (Evolutionary) [20] | Swarm Intelligence (Evolutionary Computation) | Rapid identification of near-optimal QED solutions [20] | Discrete mutation operations | No prior chemical knowledge required; fast convergence |

| Transformer/Seq2Seq (SMILES) [21] | Machine Translation (Supervised Learning) | Generates intuitive modifications via matched molecular pairs [21] | Discrete token sequence (SMILES) | Captures chemist intuition; multi-property optimization |

| VAE/Latent Space (Various) [22] | Bayesian Optimization in Latent Space | Efficient exploration of continuous chemical space [22] | Continuous latent vector | Enables smooth interpolation and gradient-based search |

| Mol-CycleGAN (Various) [19] | Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks | Lower performance vs. RL; Improvement: 1.22 ± 1.48 (P log P) [19] | Latent space translation | Learns mapping between molecular sets without paired examples |

| GraphAF/GCPN (Graph) [22] | Reinforcement Learning (Autoregressive) | High property improvement (P log P: 4.98 ± 6.49) [22] | Discrete sequential graph generation | Combines generative modeling with RL fine-tuning |

A critical differentiator among these methods is their approach to constraint handling and similarity preservation, which are crucial for practical lead optimization. Experimental comparisons on constrained optimization tasks reveal significant performance variations. For instance, when optimizing penalized logP (P log P) while maintaining structural similarity, GraphAF achieved a property improvement of 4.98 ± 6.49 with a similarity of 0.66, while GARGOYLES achieved 4.18 ± 5.84 improvement with 0.62 similarity and a 99.3% success rate [19]. These metrics highlight the trade-off between property enhancement and structural conservation that different algorithms manage through their unique variable handling strategies.

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Discrete Optimization: Reinforcement Learning on Molecular Graphs

GARGOYLES employs a graph-based deep reinforcement learning approach for molecule optimization, starting from a user-specified compound [19]. The methodology involves:

- Representation: Molecules are represented as graphs where nodes represent atoms and edges represent bonds.

- Search Algorithm: Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) guides the exploration of possible molecular modifications.

- Modification Actions: The algorithm performs discrete actions including atom addition, deletion, and bond modification, ensuring chemical validity at each step.

- Policy Network: A Graph Convolutional Network (GCN) evaluates potential modifications and directs the search toward promising regions of chemical space.

- Evaluation: Generated molecules are assessed using quantitative metrics including QED (Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness), synthetic accessibility (SA) score, and structural similarity to the starting compound.

This discrete approach maintains high structural similarity to the starting molecule (a key advantage in lead optimization) while guaranteeing 100% valid chemical structures through its graph representation [19].

Continuous Optimization: Bayesian Methods in Latent Space

Continuous optimization methods like VAE with Bayesian Optimization employ a fundamentally different strategy [22]:

- Representation Learning: A Variational Autoencoder (VAE) is trained to encode molecules into a continuous latent space, typically using SMILES strings or molecular graphs as input.

- Latent Space Properties: A predictive model maps latent representations to molecular properties of interest, creating a continuous landscape for optimization.

- Bayesian Optimization: A probabilistic model (typically a Gaussian Process) models the property function in latent space, using an acquisition function to balance exploration and exploitation.

- Candidate Selection: The algorithm selects promising latent vectors for evaluation based on expected improvement or other criteria.

- Decoding: Selected latent vectors are decoded back to molecular structures for validation and further analysis.

This approach excels in exploring diverse regions of chemical space and leverages efficient gradient-based optimization, though it may generate invalid structures without careful constraint handling [22].

Hybrid Combinatorial-Continuous Strategies

Emerging hybrid approaches like the combinatorial-continuous framework for iDMDGP (interval Discretizable Molecular Distance Geometry Problem) demonstrate the power of integrating both paradigms [23]. This method:

- Combinatorial Phase: Employs an enumeration process derived from the DMDGP, using a binary search tree explored via the Branch-and-Prune algorithm to discretely explore molecular conformations.

- Continuous Refinement: Incorporates a continuous optimization stage that minimizes a nonconvex stress function, penalizing deviations from admissible distance intervals.

- Constraint Integration: Incorporates torsion-angle intervals and chirality constraints through a refined atom ordering that preserves protein-backbone geometry.

This hybrid strategy supports systematic exploration guided by discrete structure while leveraging continuous optimization for refinement, particularly effective under wide distance bounds common in experimental NMR data [23].

Workflow and Signaling Pathways

The following diagrams illustrate the core workflows for discrete, continuous, and hybrid molecular optimization approaches.

The diagrams illustrate fundamental differences in how each approach navigates the optimization problem. Discrete methods maintain explicit structural relationships throughout the process, continuous approaches transform the problem into a smooth landscape for efficient navigation, and hybrid methods sequentially apply both strategies for enhanced robustness.

Research Reagent Solutions

The following table details essential computational tools and their functions in molecular optimization research.

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Optimization

| Research Reagent | Type | Primary Function | Key Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Graphs [19] | Data Structure | Explicitly encodes atoms (nodes) and bonds (edges) | Graph neural networks; reinforcement learning |

| SMILES Strings [21] | String Representation | Linear notation of molecular structure | Sequence-based models (Transformers, Seq2Seq) |

| Latent Space Encodings [22] | Continuous Representation | Compressed, continuous molecular features | Bayesian optimization; molecular generation |

| QED (Quantitative Estimate of Druglikeness) [20] | Metric | Composite measure of drug-likeness | Objective function for optimization |

| Structural Similarity [19] | Metric | Measures molecular structural conservation | Constrained optimization; lead optimization |

| Monte Carlo Tree Search (MCTS) [19] | Algorithm | Discrete search through decision space | Guided exploration of molecular modifications |

| Bayesian Optimization [22] | Algorithm | Global optimization of expensive black-box functions | Latent space exploration; property maximization |

These "reagents" form the foundational toolkit for constructing molecular optimization pipelines. The choice of representation (graphs, strings, or latent vectors) fundamentally constrains the types of optimization algorithms that can be effectively applied and influences the characteristics of the generated molecules.

The comparative analysis reveals that the discrete versus continuous dichotomy in molecular optimization presents researchers with complementary rather than competing strategies. Discrete methods (e.g., GARGOYLES, SIB-SOMO) excel in scenarios requiring high structural similarity to starting compounds, interpretable modification pathways, and guaranteed molecular validity. Continuous approaches (e.g., VAE with Bayesian optimization) offer superior efficiency in exploring diverse chemical spaces and leveraging gradient-based optimization but may require additional validity constraints. Emerging hybrid strategies that combine combinatorial exploration with continuous refinement demonstrate particular promise for complex problems like 3D structure determination, suggesting a future research direction where the boundaries between these paradigms become increasingly blurred. The optimal choice depends critically on specific research goals: discrete methods for lead optimization with similarity constraints, continuous approaches for de novo design of novel scaffolds, and hybrid methods for complex structural optimization with uncertain experimental data.

Methodologies in Action: Algorithms and Real-World Applications in Drug Design

The exploration of chemical space for molecular optimization is a cornerstone of drug discovery and materials science. Within this domain, a fundamental distinction exists between continuous and discrete optimization paradigms. Continuous methods often rely on gradient-based optimization in latent vector spaces, whereas discrete strategies operate directly on structured representations such as molecular graphs and strings (e.g., SMILES, SELFIES). This guide focuses on two dominant discrete-space strategies: Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and Reinforcement Learning (RL), objectively comparing their performance, experimental protocols, and applicability for molecular design tasks. GAs excel at global exploration through population-based stochastic search, while RL agents learn sequential decision-making policies through environmental interaction [24]. The choice between them hinges on critical trade-offs in sample efficiency, exploration capability, and convergence stability [25].

Core Algorithmic Comparison

Fundamental Mechanisms and Characteristics

Genetic Algorithms and Reinforcement Learning approach molecular optimization through fundamentally different mechanisms, leading to distinct performance characteristics.

Genetic Algorithms: GAs are population-based, evolutionary global optimization techniques. They maintain a pool of candidate solutions (molecules) that undergo selection, crossover, and mutation over multiple generations. The fitness of each molecule is evaluated directly by an objective function. GAs are particularly effective for combinatorial action spaces and excel at broad exploration of the chemical search space [26] [27]. Their stochastic nature helps avoid local optima but typically requires numerous fitness evaluations, leading to lower sample efficiency [25].

Reinforcement Learning: RL frames molecular generation as a sequential decision-making process where an agent learns a policy through trial-and-error interactions with an environment. The agent builds molecules step-by-step (e.g., adding atoms or bonds) and receives rewards based on the resulting molecular properties. RL methods, especially policy gradient approaches, can achieve higher sample efficiency than GAs but are more susceptible to converging to suboptimal local solutions [25] [24]. They effectively model long-range dependencies in molecular structure through architectures like transformers [28].

The table below summarizes the core methodological differences:

Table 1: Fundamental Characteristics of GA and RL

| Feature | Genetic Algorithms (GA) | Reinforcement Learning (RL) |

|---|---|---|

| Core Principle | Population-based evolutionary search | Sequential decision-making via policy optimization |

| Optimization Type | Global | Often local (can get stuck in local optima) |

| Action Space | Combinatorial, high-dimensional [26] | Discrete, continuous, or parameterized hybrid [29] |

| Sample Efficiency | Lower [25] [26] | Higher [25] |

| Key Strength | Robust global exploration | Sample efficiency and policy learning |

| Primary Weakness | Computationally intensive; no gradient use | Convergence instability; high variance in training [25] |

Performance Comparison in Molecular Optimization

Empirical studies across various molecular design tasks reveal complementary performance profiles for GA and RL approaches. The following table synthesizes quantitative results from benchmark studies, particularly those comparing stereochemistry-aware string-based models [30].

Table 2: Performance Comparison on Molecular Design Tasks

| Algorithm | Sample Efficiency | Best Performance (Task-Dependent) | Stability & Convergence | Generalization |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Genetic Algorithms | Lower; requires many fitness evaluations [25] | Superior in stereochemistry-aware analog search and synthesizable design [27] | Stable due to evolutionary mechanisms | Strong exploration aids discovery of diverse scaffolds |

| Reinforcement Learning | Higher; learns improved policy from fewer samples [25] | Excels in targeted tasks like drug rediscovery and multi-property optimization [30] [28] | Sensitive to hyperparameters; can be unstable [25] | Can overfit to reward function, leading to reward hacking [30] |

| Hybrid Methods (GA+RL) | Moderate; enhanced by RL guidance [26] [31] | State-of-the-art on various benchmarks (e.g., TSP, CVRP, molecular design) [26] | More stable than RL alone [26] | Combines RL's efficiency with GA's exploratory power |

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Standardized Experimental Setups

To ensure fair comparison between GA and RL methodologies, researchers have developed standardized benchmarking frameworks and experimental protocols.

Benchmarking Tasks and Datasets:

- The GuacaMol benchmark provides well-established goal-directed tasks for drug design, including drug rediscovery, isomer identification, and multi-property optimization [28].

- Stereochemistry-aware benchmarks introduce novel fitness functions based on circular dichroism spectra to evaluate performance on stereochemistry-sensitive tasks, using datasets derived from ZINC15 [30].

- Combinatorial optimization benchmarks include problems like the Traveling Salesman Problem (TSP) and Capacitated Vehicle Routing Problem (CVRP) for testing general discrete optimization capabilities [26].

Evaluation Metrics:

- Chemical Metrics: Validity, novelty, diversity, and similarity to known molecules [30].

- Objective Performance: Success in optimizing specific chemical properties (e.g., binding affinity, solubility, optical activity) [30].

- Optimization Efficiency: Number of samples required to reach objective, wall-clock time, and convergence stability [25].

Key Algorithm Workflows

The fundamental workflows for GA and RL in molecular optimization can be visualized as follows:

Diagram 1: Genetic Algorithm Workflow

Diagram 2: Reinforcement Learning Workflow

Advanced Hybrid Strategies

Synergizing GA and RL Approaches

Recent research demonstrates that combining GA and RL can overcome the limitations of either approach used independently. The Evolutionary Augmentation Mechanism (EAM) is a plug-and-play framework that synergizes the learning efficiency of DRL with the global search power of GAs [26]. In EAM, solutions generated from a learned RL policy are refined through domain-specific genetic operations like crossover and mutation. These evolved solutions are then selectively reinjected into the policy training loop, enhancing exploration and accelerating convergence [26].

Another hybrid approach uses RL to enhance GA cluster selection in molecular searches. This method clusters the initial population and uses RL with a dynamically adjusted probability to select clusters for evolutionary runs, effectively balancing exploration and exploitation [31]. Experimental results show this RL-enhanced approach outperforms unclustered evolutionary algorithms for specific molecular searches like quinoline-like structure optimization [31].

Visualization of Hybrid Methodology

Diagram 3: GA-RL Hybrid Feedback Loop

The Scientist's Toolkit

Successful implementation of GA and RL strategies for molecular optimization requires specific computational tools and resources. The table below details key components of the research toolkit:

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Discrete Molecular Optimization

| Tool Category | Specific Tools/Resources | Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| Molecular Representations | SMILES, SELFIES, GroupSELFIES [30] | String-based encoding of molecular structure for sequence-based models |

| Graph Representations | Hydrogen-suppressed molecular graphs [28] | Native representation of atoms and bonds for graph-based models |

| Cheminformatics Libraries | RDKit [30] | Molecule manipulation, stereochemistry handling, and property calculation |

| Benchmarking Suites | GuacaMol [28], stereochemistry-aware benchmarks [30] | Standardized evaluation and comparison of algorithm performance |

| Reaction Templates | Expert-defined SMARTS strings [27] | Enforcement of synthesizability constraints in template-based models |

| Building Block Catalogs | Purchasable building blocks (e.g., ZINC15 subset [30]) | Constrained search spaces ensuring synthetic feasibility |

Implementation Considerations

When implementing these discrete optimization strategies, researchers should consider several practical aspects:

Computational Resources: RL methods, particularly those using deep transformer architectures, often require significant GPU resources for training [28], while GAs are more CPU-intensive and can be highly parallelized [25].

Synthesizability Enforcement: Template-based methods like SynGA [27] explicitly constrain the search to synthesizable molecules by operating directly on synthesis routes, whereas string-based approaches often require post-hoc synthesizability assessment.

Stability Techniques: For RL training, methods like policy mirror descent [32] and trust region constraints [25] help stabilize training and prevent performance collapse.

Genetic Algorithms and Reinforcement Learning offer complementary strengths for molecular optimization in discrete spaces. GAs provide robust global exploration capabilities particularly valuable for novel scaffold discovery and stereochemistry-aware design, while RL achieves higher sample efficiency for targeted optimization tasks. The emerging trend of hybrid approaches demonstrates state-of-the-art performance by combining the learning efficiency of RL with the global search power of GAs.

The choice between these strategies depends on specific research priorities: when sample efficiency is paramount and the reward function can be carefully shaped, RL may be preferable; when exploring diverse chemical space or working with complex combinatorial actions, GAs often excel. For the most challenging molecular optimization problems, hybrid methodologies that leverage both approaches show significant promise for advancing drug discovery and materials design.

The exploration of chemical space for novel drug candidates represents a monumental challenge in pharmaceutical research, given its vastness and high-dimensional, discrete nature. In response, deep generative models, particularly Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), have emerged as transformative tools. They address this challenge by mapping discrete molecular structures into a continuous latent space, enabling the application of efficient, gradient-based optimization techniques to navigate the complex landscape of molecular properties [33] [14]. This guide provides a detailed comparison of these continuous space strategies, framing them within the broader research context of continuous versus discrete molecular optimization. We objectively evaluate their performance, supported by experimental data and detailed methodologies, to inform researchers, scientists, and drug development professionals.

Model Architectures and Fundamental Differences

At their core, both VAEs and GANs are deep generative models, but they employ fundamentally different architectures and learning objectives to achieve molecular generation.

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs)

VAEs are probabilistic models based on an encoder-decoder architecture. The encoder compresses an input molecule (e.g., represented as a SMILES string or graph) into a probability distribution in a low-dimensional latent space, characterized by a mean (µ) and variance (σ²). A latent vector z is sampled from this distribution and passed to the decoder, which reconstructs the original molecule [34] [35]. The VAE loss function combines a reconstruction loss (measuring the fidelity of the reconstructed molecule) and a Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence term, which regularizes the latent space by pushing the learned distribution toward a prior, typically a standard normal distribution [34]. This structured latent space facilitates meaningful interpolation and exploration.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs)

GANs consist of two neural networks, a Generator and a Discriminator, engaged in an adversarial game. The Generator takes a random noise vector as input and aims to produce realistic synthetic molecules. The Discriminator's role is to distinguish between real molecules from the training data and fake ones produced by the Generator [35]. The training process is a two-player minimax game: the Generator strives to fool the Discriminator, while the Discriminator improves its鉴别能力. This competition drives both networks to improve, ideally resulting in a Generator that can produce highly realistic molecules [35].

Table 1: Fundamental Architectural Differences Between VAEs and GANs

| Feature | VAEs | GANs |

|---|---|---|

| Architecture | Encoder-Decoder [35] | Generator-Discriminator [35] |

| Learning Objective | Likelihood maximization with KL regularization [34] [35] | Adversarial, two-player minimax game [35] |

| Latent Space | Explicit, probabilistic (e.g., Gaussian) [35] | Implicit, often random noise input [35] |

| Training Stability | Generally more stable due to a well-defined loss function [35] | Can be unstable; prone to mode collapse [35] [36] |

| Sample Quality | Can sometimes be blurrier but more diverse [36] | Often high-quality and sharp [35] |

| Output Diversity | Better coverage of data distribution, less prone to mode collapse [35] | High potential for mode collapse (limited diversity) [35] [36] |

Performance and Experimental Data Comparison

Empirical evaluations across various molecular design tasks reveal the distinct strengths and weaknesses of VAE and GAN-based approaches.

Performance Metrics in Molecular Generation

Key metrics for assessing generative models in de novo drug design include validity (the percentage of generated molecules that are chemically legitimate), uniqueness (the proportion of novel molecules not found in the training set), and internal diversity (a measure of the structural variety within a set of generated molecules) [37].

Comparative Performance Data

Recent studies highlight the performance of advanced implementations of both models. The PCF-VAE, a posterior collapse-free model, demonstrates a validity of 98.01% and uniqueness of 100% at high diversity levels, with internal diversity (intDiv2) metrics ranging from 85.87% to 86.33% [37]. Conversely, the VGAN-DTI framework, which integrates VAEs and GANs with Multilayer Perceptrons (MLPs) for drug-target interaction prediction, reported an accuracy of 96%, with precision, recall, and F1 scores all exceeding 94% [34]. Another approach using a hybrid VAE with iterative weighted retraining was shown to effectively push the Pareto front for multiple molecular properties, demonstrating its capability in complex multi-objective optimization [33].

Table 2: Experimental Performance Comparison of Select VAE and GAN Models

| Model | Model Type | Key Task | Performance Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|

| PCF-VAE [37] | VAE | De novo molecule generation | Validity: 98.01%Uniqueness: 100%Internal Diversity (intDiv2): 85.87-86.33% |

| VGAN-DTI [34] | Hybrid (GAN+VAE+MLP) | Drug-Target Interaction Prediction | Accuracy: 96%Precision: 95%Recall: 94%F1-Score: 94% |

| Multi-Objective LSO [33] | VAE (JT-VAE) with Latent Space Optimization | Multi-property molecular optimization | Effectively pushes the Pareto front for jointly optimizing multiple properties. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

To ensure reproducibility and provide a clear "scientist's toolkit," this section outlines the standard methodologies for implementing and testing these models.

Protocol 1: Training a VAE for Molecular Generation

This protocol is based on methodologies described for JT-VAE and PCF-VAE [33] [37].

- Data Preparation: A dataset of molecules (e.g., from ZINC or ChEMBL) is converted into a standardized representation, most commonly SMILES strings. These strings are often preprocessed into variants like GenSMILES to reduce complexity and incorporate key physicochemical properties such as molecular weight, LogP, and TPSA [37].

- Model Initialization: The VAE is initialized with an encoder and decoder network. The encoder typically consists of several fully connected layers with ReLU activation, outputting parameters (µ and log σ²) for the latent distribution. The decoder, often a Graph Neural Network (e.g., in JT-VAE) or an RNN, is designed to reconstruct the molecular graph or sequence [33] [37].

- Training Loop: For each batch in the training dataset:

- Forward Pass: Input data is passed through the encoder to obtain µ and log σ². A latent vector

zis sampled using the reparameterization trick:z = µ + σ ⋅ ε, where ε ~ N(0, I). - Reconstruction: The decoder reconstructs the molecule from

z. - Loss Calculation: The loss is computed as

Loss = Reconstruction_Loss + β * KL_Divergence, where β may be a weighting factor to mitigate posterior collapse [37]. - Backward Pass & Optimization: Model parameters are updated via gradient descent using an optimizer like Adam [37].

- Forward Pass: Input data is passed through the encoder to obtain µ and log σ². A latent vector

- Validation: The trained model is evaluated on a hold-out test set using metrics like validity, uniqueness, and diversity [37].

Protocol 2: Training a GAN for Molecular Generation

This protocol follows the adversarial training paradigm as detailed in the search results [35].

- Data Preparation: Similar to the VAE protocol, a dataset of molecular representations is prepared.

- Model Initialization: Both the Generator (

G) and Discriminator (D) networks are initialized.Gis typically a fully connected network that maps a noise vector to a molecular representation, whileDis a classifier that outputs a probability of the input being real [35]. - Adversarial Training Loop: For each training iteration:

- Train Discriminator (

D):- Sample a batch of real molecules

x_realfrom the data. - Generate a batch of fake molecules

x_fake = G(z)from random noisez. - Compute Discriminator loss

L_D = -[log D(x_real) + log(1 - D(x_fake))]. - Update

D's parameters by ascending the gradient ofL_D.

- Sample a batch of real molecules

- Train Generator (

G):- Generate another batch of fake molecules

x_fake = G(z). - Compute Generator loss

L_G = -log D(x_fake)to fool the discriminator. - Update

G's parameters by descending the gradient ofL_G[35].

- Generate another batch of fake molecules

- Train Discriminator (

- Evaluation: The quality of the generated molecules from

Gis assessed through validity checks, property prediction, and diversity measures.

Protocol 3: Latent Space Optimization (LSO) for Multi-Objective Property Enhancement

This protocol enhances a pre-trained VAE (like JT-VAE) to generate molecules with optimized properties [33] [38].

- Pre-training: A VAE is first trained on a large dataset of molecules to learn a general chemical space [33].

- Property Prediction: A predictor network is trained to map points in the latent space to one or more target properties of interest [33].

- Latent Space Navigation:

- Bayesian Optimization (BO): An acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) guides the search for latent points

zthat maximize the predicted property values. BO is sample-efficient, making it suitable for expensive-to-evaluate properties [33]. - Particle Swarm Optimization (PSO): A population-based search algorithm can also be used to explore the latent space, particularly for multi-objective problems where objectives are combined via scalarization [33].

- Bayesian Optimization (BO): An acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) guides the search for latent points

- Weighted Retraining: To prevent the generative model from deviating into chemically unrealistic regions, the original training dataset is periodically augmented with newly generated, high-scoring molecules. Each data point is weighted, for instance, based on its Pareto efficiency in a multi-objective setting. The VAE is then retrained on this weighted dataset, effectively reshaping the latent space to better accommodate molecules with desired properties [33].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This section details key computational tools and resources used in the experiments cited throughout this guide.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Item/Resource | Function/Description | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| JT-VAE (Junction-Tree VAE) [33] [38] | A generative model that encodes/decodes molecular graphs directly, ensuring high validity by first generating a molecular scaffold. | Serves as the base generative model for latent space optimization in multi-property molecular design [33]. |

| BindingDB [34] | A public database of measured binding affinities for drug-target interactions. | Used as a labeled dataset to train and validate MLP classifiers for predicting binding affinities in the VGAN-DTI framework [34]. |

| ChEMBL [39] | A large-scale bioactivity database for drug discovery. | Provides a source of bioactive compound data for training predictive models in drug discovery tasks [39]. |

| RDKit [39] | An open-source cheminformatics toolkit. | Used to calculate molecular descriptors and process SMILES strings from chemical databases [39]. |

| SMILES/GenSMILES [37] | String-based representations of molecular structure. GenSMILES is a preprocessed version that reduces complexity. | Serves as the primary input representation for many VAEs and GANs. GenSMILES helps improve model performance [37]. |

| MOSES Benchmark [37] | Molecular Sets (MOSES) - a standardized benchmark for evaluating molecular generative models. | Used to objectively compare the performance (validity, uniqueness, diversity) of new models like PCF-VAE against state-of-the-art [37]. |

Molecular optimization represents a critical stage in the drug discovery pipeline, focusing on the structural refinement of lead compounds to enhance their properties. Traditional molecular optimization methods have largely operated on one-dimensional string representations (e.g., SMILES) or two-dimensional graph structures, fundamentally limiting their ability to account for the three-dimensional spatial arrangements that dictate molecular interactions and binding affinities. Structure-based molecule optimization (SBMO) has emerged as a transformative paradigm that directly addresses this limitation by leveraging 3D structural information of protein targets to guide the optimization process [40] [1]. This approach marks a significant departure from conventional methods by explicitly considering the continuous spatial coordinates and discrete atom types that jointly determine molecular geometry and function.

The evolution of SBMO has brought to the forefront a fundamental dichotomy in computational approaches: discrete versus continuous optimization strategies. Discrete methods operate directly on molecular structures through sequential modifications, while continuous approaches leverage differentiable latent spaces to navigate the chemical landscape. This comparative guide examines the MolJO (Molecule Joint Optimization) framework within this broader context, analyzing how its unique integration of 3D structural awareness with a continuous, gradient-based optimization strategy addresses longstanding challenges in structure-based drug design [40] [41]. Through systematic performance comparisons and methodological analysis, we elucidate how MolJO establishes new state-of-the-art benchmarks while demonstrating versatility across multiple drug design scenarios, including R-group optimization and scaffold hopping.

Methodological Framework: MolJO's Architecture and Key Innovations

Core Technical Foundation

MolJO represents a groundbreaking gradient-based framework for SBMO that operates within a continuous and differentiable space derived through Bayesian inference [40] [41]. At its core, MolJO addresses two fundamental challenges that have historically limited the application of gradient guidance to molecular optimization: (1) the difficulty of applying gradient-based methods to discrete variables (atom types), and (2) the risk of inconsistencies between continuous (coordinates) and discrete (types) modalities during optimization [40]. The framework leverages Bayesian Flow Networks to create a unified parameter space that facilitates joint guidance signals across different molecular modalities while preserving SE(3)-equivariance—a crucial property ensuring that molecular representations remain consistent across rotations and translations [40] [42].

The technical architecture of MolJO processes 3D protein-ligand complexes represented as structured point clouds. Proteins are represented as binding sites containing Np atoms with 3D coordinates and Kp-dimensional atom features, while ligands contain Nm atoms with both spatial coordinates and type information [40]. This structured representation enables the model to capture intricate geometric relationships and atomic-level interactions that determine binding affinity and molecular properties.

The Backward Correction Strategy

A pivotal innovation introduced in MolJO is the backward correction strategy, which optimizes within a sliding window of past histories during the generation process [40] [41]. This approach maintains explicit dependencies on previous steps, effectively aligning gradients across the optimization trajectory and mitigating the risk of inconsistencies between molecular modalities. The backward correction mechanism enables a flexible trade-off between exploration and exploitation—allowing the model to explore diverse molecular regions while progressively refining toward optimal solutions [40]. This strategic balance is particularly valuable in drug discovery contexts where both molecular diversity and property optimization are critical objectives.

Table 1: Core Technical Components of the MolJO Framework

| Component | Technical Implementation | Functional Role |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Flow Networks | Continuous, differentiable parameter space derived through Bayesian inference | Unifies continuous and discrete molecular modalities; enables gradient propagation |

| SE(3)-Equivariance | Geometric deep learning architectures that preserve transformation equivariance | Ensures consistent molecular representations under rotational and translational transformations |

| Backward Correction | Sliding window optimization over past histories | Aligns gradients across optimization steps; balances exploration and exploitation |

| Joint Guidance | Simultaneous gradient signals for coordinates and atom types | Prevents modality inconsistencies; enables cohesive molecular optimization |

Experimental Benchmarking: Protocols and Performance Metrics

Evaluation Framework and Benchmarks

The performance of MolJO was rigorously evaluated on the CrossDocked2020 benchmark, a widely adopted standard in structure-based drug design that contains protein-ligand complexes with precise binding poses and affinity measurements [40] [43]. Experimental protocols followed established practices for fair comparison, with models tasked with generating optimized molecular structures for given protein binding pockets. The evaluation incorporated multiple critical metrics to comprehensively assess different aspects of optimization performance:

- Vina Dock Score: Molecular docking scores calculated using AutoDock Vina, representing predicted binding affinity (lower scores indicate stronger binding) [40] [43]

- Success Rate: Percentage of generated molecules that satisfy predefined criteria for binding affinity, structural validity, and synthetic accessibility [40]

- Synthetic Accessibility (SA) Score: Quantitative measure estimating the ease of synthesizing generated molecules (higher scores indicate greater synthesizability) [40]

- "Me-Better" Ratio: Proportion of generated molecules that simultaneously improve multiple properties compared to the initial lead compound [40] [41]

Comparative Performance Analysis

MolJO established new state-of-the-art performance across all major evaluation metrics, demonstrating substantial improvements over existing approaches. On the CrossDocked2020 benchmark, MolJO achieved a remarkable success rate of 51.3%, representing more than a 4× improvement compared to gradient-based counterparts [40] [43]. The framework attained a Vina Dock score of -9.05, indicating strong predicted binding affinity, while maintaining a high synthetic accessibility score of 0.78—balancing potency with practical synthesizability [40]. Perhaps most impressively, MolJO achieved a "Me-Better" ratio that was twice as high as other 3D baselines, highlighting its ability to simultaneously optimize multiple molecular properties [40] [41].

Table 2: Performance Comparison on CrossDocked2020 Benchmark

| Method | Vina Dock Score | Success Rate | SA Score | "Me-Better" Ratio |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MolJO | -9.05 | 51.3% | 0.78 | 2.0× |

| TAGMol | Not Reported | ~12.8% (est.) | Not Reported | 1.0× (baseline) |

| DiffSBDD | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

| DecompOpt | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported | Not Reported |

The experimental analysis revealed that MolJO's joint optimization approach effectively addressed limitations observed in previous gradient-based methods. Specifically, methods like TAGMol that applied gradient guidance exclusively to continuous coordinates struggled to optimize overall molecular properties, despite improvements in Vina affinities [40]. This limitation stemmed from disconnected guidance signals between atomic coordinates and types—precisely the challenge that MolJO's unified framework resolves through its Bayesian-derived continuous space and backward correction strategy.

The Continuous vs. Discrete Paradigm: Contextualizing MolJO's Approach

The Discrete Optimization Landscape

Traditional discrete optimization methods for molecular design operate directly on molecular representations such as SMILES strings, SELFIES, or molecular graphs [1] [2]. These approaches include genetic algorithm (GA)-based methods that generate new molecules through crossover and mutation operations, as well as reinforcement learning (RL)-based methods that navigate the discrete chemical space through sequential decision-making [1]. For instance, frameworks like MOLRL leverage proximal policy optimization (PPO) to optimize molecules in the latent space of pre-trained generative models, demonstrating competitive performance on benchmark tasks [2].

While discrete methods have shown promise in various molecular optimization tasks, they face fundamental limitations in structure-based applications. The primary challenge lies in their inability to directly incorporate and leverage 3D structural information about protein-ligand interactions [40] [1]. Additionally, discrete optimization often requires extensive oracle calls or property evaluations, making them computationally expensive for complex molecular systems [40] [1].

MolJO's Continuous Differentiation

MolJO fundamentally operates within the continuous optimization paradigm, leveraging a differentiable parameter space that enables efficient gradient-based navigation of the chemical landscape [40] [41]. This continuous approach provides several distinct advantages for structure-based optimization:

- Unified Molecular Representation: By deriving a continuous space through Bayesian inference, MolJO seamlessly integrates both coordinate and type information within a cohesive framework [40]

- Gradient-Based Efficiency: The use of gradient signals enables more efficient optimization compared to evolutionary or RL-based methods that rely on sampling and evaluation [40] [41]

- 3D Geometric Awareness: The preservation of SE(3)-equivariance ensures that all generated molecules respect the fundamental geometric constraints of molecular systems [40] [42]

The following diagram illustrates MolJO's continuous optimization workflow and its contrast with discrete approaches:

MolJO Continuous vs. Discrete Optimization