Brownian Motion in Molecular Machines: From Thermal Noise to Biological Function and Therapeutic Targeting

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Brownian motion's multifaceted role in molecular machines, targeting researchers and drug development professionals.

Brownian Motion in Molecular Machines: From Thermal Noise to Biological Function and Therapeutic Targeting

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of Brownian motion's multifaceted role in molecular machines, targeting researchers and drug development professionals. We first establish the foundational physics of thermal fluctuations and their energetic implications in the crowded cellular environment. We then explore advanced computational and experimental methodologies for quantifying and visualizing stochastic dynamics in systems like molecular motors, ribosomes, and chaperonins. The discussion addresses key challenges in distinguishing functional Brownian motion from deleterious noise and strategies for optimizing machine efficiency. Finally, we critically compare and validate mechanistic models against experimental data, highlighting implications for designing allosteric drugs and understanding disease-related malfunctions. This synthesis bridges physical theory with biomedical application, offering a roadmap for leveraging stochasticity in therapeutic innovation.

The Physics of Chance: Defining Brownian Motion's Role in Molecular Machine Energetics

The study of Brownian motion is not merely a historical footnote in physics but a foundational pillar for understanding the operational milieu of biological molecular machines. This whitepaper posits that a rigorous, quantitative understanding of Brownian dynamics is essential for interpreting single-molecule biophysics, rational drug design targeting intrinsically disordered regions, and the engineering of synthetic cellular systems. The journey from Einstein's theoretical formalism and Perrin's experimental validation to modern intracellular applications provides the necessary conceptual toolkit for researchers in molecular machines and drug development.

Foundational Theory: The Einstein-Smoluchowski Framework

Einstein’s 1905 treatment modeled pollen particles as large molecules in thermal equilibrium with surrounding solvent molecules. The central result connects macroscopic diffusion to microscopic atomic kinetics.

Key Equations:

- Mean-Squared Displacement (MSD):

<Δx²> = 2Dτ(for one dimension), whereΔxis displacement in timeτ, andDis the diffusion coefficient. - Stokes-Einstein Relation:

D = k_B T / (6πηr), wherek_Bis Boltzmann's constant,Tis temperature,ηis dynamic viscosity, andris the hydrodynamic radius of the particle. - Einstein’s Diffusion Formula (Perrin's Verification):

D = (RT)/(6πηr N_A), linking the gas constantRand Avogadro's numberN_A.

These equations established that the ceaseless, random motion observed is a direct consequence of thermal energy and provided a method to determine N_A.

Perrin’s Experimental Validation: Protocol and Data

Jean Perrin’s 1908-1909 experiments provided definitive proof of the atomic theory by verifying Einstein's predictions.

Experimental Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: A dilute aqueous suspension of gamboge or mastic resin particles of uniform size (approx. 0.5 µm diameter) was prepared and placed in a sealed, flat glass cell.

- Microscopy and Tracking: Using a dark-field microscope with an oil-immersion objective, the motion of individual particles was observed. Their positions were recorded at regular time intervals (e.g., every 30 seconds) by hand-drawing on paper or using a camera lucida.

- Trajectory Analysis: Starting from an origin, the square of the net displacement (

r²) afterntime intervals was calculated for many particles and starting times. The mean of these squared displacements was computed. - Calculating Avogadro's Number: Using the measured mean-squared displacement, time interval, viscosity, temperature, and particle radius (estimated via Stokes' law sedimentation rates),

N_Awas calculated via Einstein's diffusion formula.

Table 1: Summary of Perrin's Key Experimental Data (Adapted)

| Experiment Reference | Particle Type | Mean Squared Displacement Data | Calculated N_A (mol⁻¹) | Modern Value (mol⁻¹) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Perrin (1908) | Gamboge, r ~0.212 µm | <r²> for τ=30s measured |

6.5 - 7.2 x 10²³ | 6.022 x 10²³ |

| Perrin (1909) | Mastic, r ~0.52 µm | MSD from trajectory plots | ~6.0 - 6.8 x 10²³ | 6.022 x 10²³ |

Diagram Title: Perrin's Experimental Workflow for N_A

Brownian Motion in the Nanoscale Cellular Environment

Within the cell, molecular machines (proteins, ribosomes, molecular motors) operate in a crowded, viscoelastic medium. The simple Stokes-Einstein relation often breaks down, requiring advanced models.

Key Deviations and Models:

- Anomalous Diffusion: MSD follows

<r²> ∝ τ^α, whereα < 1indicates sub-diffusion (common in cytosol and membranes due to crowding, binding, and viscoelasticity). - Viscoelasticity: The cytoplasm behaves as a complex fluid with memory, modeled by Generalized Langevin Equations or fractional Brownian motion.

- Confinement and Compartmentalization: Organelles and cytoskeletal corrals restrict free diffusion, leading to hop diffusion (e.g., in plasma membranes).

Table 2: Diffusion Regimes in Cellular Environments

| Environment | Approx. Viscosity (η relative to water) | Typical Diffusion Coefficient (D) for a 50 kDa protein | MSD Exponent (α) | Primary Cause of Anomaly |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Free aqueous solution | 1 cP (ref) | ~50-100 µm²/s | ~1.0 | N/A (Normal diffusion) |

| Cytosol (mammalian) | 2-10 cP | ~5-20 µm²/s | 0.7-0.9 | Macromolecular crowding, transient binding |

| Nucleoplasm | 5-20 cP | ~2-10 µm²/s | 0.6-0.8 | Chromatin mesh, crowding |

| Plasma Membrane | N/A (2D) | ~0.01-0.1 µm²/s | Varies; can be ~0.7-1.0 | Cytoskeletal "pickets and fences", lipid composition |

| Mitochondrial Matrix | High crowding | < 5 µm²/s | ~0.5-0.8 | Extreme protein crowding |

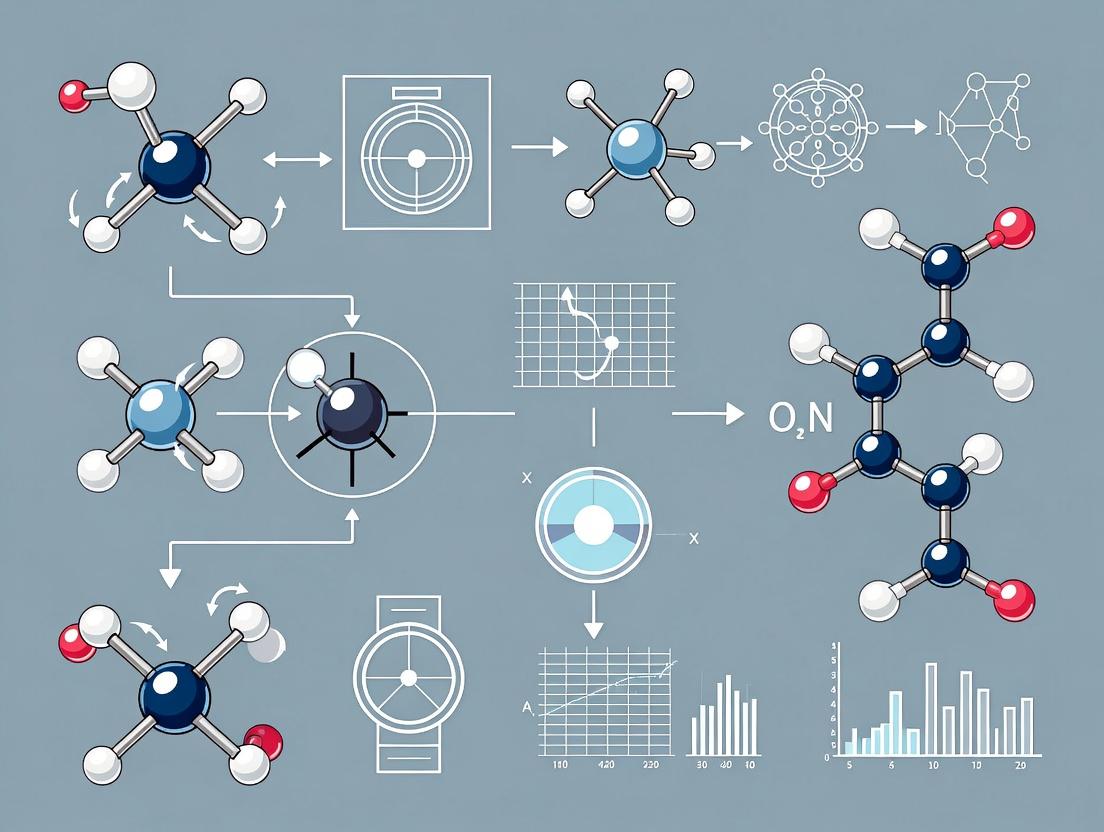

Diagram Title: Cellular Causes of Anomalous Brownian Motion

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions for Modern Brownian Motion Studies

Table 3: Essential Reagents and Tools for Intracellular Diffusion Studies

| Item / Reagent | Function / Rationale | Example Application |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorescent Nanospheres (e.g., TetraSpeck, FluoSpheres) | Calibrated size standards for measuring local viscosity via Stokes-Einstein relation. | Mapping cytoplasmic viscosity gradients. |

| Genetically Encoded Fluorescent Proteins (FPs: eGFP, mCherry) | Fuse to protein of interest for in vivo tracking via FCS or SPT. | Measuring diffusion of specific endogenous proteins. |

| HaloTag/SNAP-tag Ligands (Janelia Fluor, SiR dyes) | Covalent, cell-permeable fluorescent labels for specific protein tagging in live cells. | Single-particle tracking (SPT) with high photon budget. |

| Methylene Blue / Paraquat | Inducers of controlled oxidative stress to alter cytosolic crowding/viscosity. | Studying diffusion changes under stress conditions. |

| Polyethylene Glycol (PEG) / Dextran | Macromolecular crowding agents for in vitro reconstitution experiments. | Mimicking intracellular crowding in test-tube assays. |

| Lattice Light-Sheet Microscope | Enables high-speed, low-phototoxicity 3D imaging of particle dynamics. | Tracking vesicles or proteins in 3D over long durations. |

| Fluorescence Correlation Spectroscopy (FCS) Software | Analyzes intensity fluctuations to extract diffusion coefficients and concentrations. | Quantifying dynamics of freely diffusing molecules in sub-femtoliter volumes. |

| uTrack / TrackMate (Software) | Algorithms for linking particle positions into trajectories from SPT movies. | Automated analysis of single-molecule diffusion paths. |

Advanced Experimental Protocol: Single-Particle Tracking (SPT) in Live Cells

Objective: To quantify the diffusion dynamics of a membrane receptor in the live cell plasma membrane.

Detailed Methodology:

- Labeling: Express the receptor of interest fused to HaloTag. Incubate live cells with a pulsed, low concentration (0.5-5 nM) of a bright, photostable cell-permeable HaloTag ligand (e.g., JF549).

- Imaging: Use a TIRF (Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence) microscope equipped with a sensitive EMCCD or sCMOS camera. Image at a high frame rate (e.g., 50-100 Hz) with minimal laser power to minimize photobleaching and track single molecules.

- Localization: For each frame, identify fluorescent spots. Fit their point spread function (PSF) with a 2D Gaussian to determine centroid coordinates with nanometer precision (~10-30 nm).

- Trajectory Reconstruction: Use tracking software (e.g., uTrack) to link localizations between consecutive frames based on maximum displacement and other probabilistic parameters.

- MSD Analysis: For each trajectory

i, calculate MSD as:<r²(τ)>_i = (1/(N-τ)) Σ [ (x(t+τ) - x(t))² + (y(t+τ) - y(t))² ]. Average MSD over all trajectories. - Model Fitting: Fit the averaged MSD curve to appropriate models (e.g., free diffusion: MSD=4Dτ; anomalous: MSD=4Γτ^α; confined: MSD=Rc²(1 - A1*exp(-4A2Dτ/Rc²)) ).

Diagram Title: Single-Particle Tracking (SPT) Analysis Workflow

The evolution from Einstein's theoretical particles to Perrin's tracked beads and now to single-molecule trajectories in cells underscores a critical thesis: Molecular machines do not operate in a vacuum but in a stochastic, crowded, and force-prone environment. Their efficiency, fidelity, and regulation are inextricably linked to Brownian motion. For drug development, this understanding is pivotal. Targeting weakly structured regions of proteins (intrinsically disordered regions) or designing allosteric modulators requires accounting for the conformational search dynamics driven by Brownian motion. Furthermore, drug efficacy can be influenced by its own diffusion through the crowded cytosol or nucleoplasm. A quantitative grasp of these principles, rooted in a century-old physics discovery, is therefore indispensable for the next generation of biophysical research and therapeutic design.

The study of molecular machines—from kinesin walking on microtubules to the rotary action of ATP synthase—is fundamentally a study of Brownian motion in a structured energy landscape. The broader thesis posits that thermal noise is not an impediment to function but the primary fuel for directed motion and mechanochemical coupling. This whitepaper elaborates on the energy landscape paradigm and details experimental methodologies for quantifying stochastic steering.

The Energy Landscape Paradigm

Molecular machines operate on a complex, multi-dimensional free energy surface defined by chemical and mechanical coordinates. Thermal fluctuations (Brownian motion) enable the system to explore this landscape. Asymmetric potentials, often modulated by substrate binding or hydrolysis, then "rectify" this Brownian exploration into directed work.

Table 1: Key Energy Scales in Molecular Machine Operation

| Energy Term | Typical Magnitude (kᵦT at 300K) | Description |

|---|---|---|

| Thermal Energy (kᵦT) | 1 (≈ 4.11 pN·nm) | Baseline energy for stochastic fluctuations. |

| Chemical Step (e.g., ATP hydrolysis) | 20-25 kᵦT | Total free energy released from fuel molecule. |

| Mechanical Step (e.g., kinesin stride) | 2-6 kᵦT | Energy required for sub-steps like lever arm movement. |

| Activation Barrier | 10-20 kᵦT | Barrier height between functional states. |

| Binding Energy (Ligand-Protein) | 5-15 kᵦT | Stabilization energy from substrate binding. |

Core Experimental Protocols

Single-Molecule FRET (smFRET) to Map Conformational Landscapes

Objective: Measure real-time conformational dynamics and state occupancies. Protocol:

- Labeling: Site-specifically label protein of interest with donor (e.g., Cy3) and acceptor (e.g., Cy5) fluorophores using cysteine-maleimide chemistry.

- Immobilization: Tether labeled molecules to a passivated (PEG-coated) quartz slide via a biotin-streptavidin linkage.

- Imaging: Use a total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope with alternating laser excitation (ALEX) to minimize heterogeneity.

- Data Acquisition: Record emission intensities (I_donor, I_acceptor) at 10-100 ms time resolution.

- Analysis: Calculate FRET efficiency E = I_acceptor / (I_donor + I_acceptor). Use hidden Markov modeling (HMM) to identify discrete states and transition rates.

Optical Tweezers Force Spectroscopy

Objective: Apply controlled forces to measure mechanical transitions and work output. Protocol:

- Handle Attachment: Construct DNA/RNA handles (≈ 1 kbp) labeled with digoxigenin and biotin at opposite ends.

- Machine Tethering: Attach handles to specific residues on the molecular machine via engineered cysteine tags or fusion proteins.

- Trap Formation: Capture polystyrene beads coated with anti-digoxigenin/streptavidin in two optical traps (1064 nm laser).

- Force-Ramp/F-Clamp Experiments: Move one trap relative to the other at constant velocity (force ramp) or maintain constant force (force clamp).

- Data Analysis: Record bead displacement with nm precision. Construct force-extension curves or detect sudden steps in displacement. Calculate work from area under force-extension curve.

Cryo-Electron Microscopy (cryo-EM) for Structural Ensembles

Objective: Resolve multiple conformational states populated stochastically. Protocol:

- Vitrification: Apply 3-4 µL of sample to a glow-discharged grid, blot, and plunge-freeze in liquid ethane.

- Data Collection: Acquire thousands of movie micrographs on a 300 keV cryo-TEM with a direct electron detector.

- Image Processing: Use motion correction and CTF estimation. Perform 2D classification to isolate particles. Perform 3D heterogeneous refinement to separate distinct conformational classes without imposing symmetry.

- Model Building: Fit atomic models into density maps for each major class to define states on the energy landscape.

Visualization of Core Concepts

Diagram Title: Energy Landscape of a Molecular Machine Cycle

Diagram Title: Experimental Quantification Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents and Materials for Key Experiments

| Item | Supplier Examples | Function in Experiment |

|---|---|---|

| Maleimide-activated Fluorophores (Cy3, Cy5, Alexa dyes) | Cytiva, Thermo Fisher | Covalent, site-specific labeling of cysteine residues for smFRET. |

| PEG/Biotin-PEG Passivation Mix | Laysan Bio, Sigma-Aldrich | Creates inert, non-sticking surface on slides/beads; enables biotin tethering. |

| Streptavidin-coated Polystyrene Beads | Spherotech, Bangs Labs | Provides strong, specific attachment point for biotinylated handles in optical traps. |

| Monoclonal Anti-Digoxigenin Antibody | Roche, Sigma-Aldrich | Used to functionalize beads/handles for digoxigenin-based tethering in force assays. |

| Long DNA Handles (PCR kits for labeled templates) | Jena Bioscience, NEB | Provides flexible, defined-length tethers for single-molecule manipulation. |

| Zero-Length Crosslinkers (EDC/NHS) | Thermo Fisher | For covalent stabilization of transient complexes prior to Cryo-EM grid preparation. |

| HMM Analysis Software (e.g., vbFRET, HaMMy) | Open Source, NIH | Statistical tool for identifying discrete states and transitions from noisy time traces. |

| TIRF Microscope with ALEX capability | Nikon, Olympus, Custom-built | Enables single-molecule fluorescence imaging with minimal background. |

Within the crowded cellular environment, biological systems have evolved to harness the random, thermal noise of Brownian motion to drive directed mechanical work. This whitepaper provides an in-depth technical analysis of four canonical molecular machines—kinesin, myosin, ATP synthase, and the CRISPR-Cas9 system—framed within the thesis that stochastic thermal fluctuations are not merely a nuisance but a fundamental design principle for nanoscale biological function. We detail quantitative biophysical parameters, experimental methodologies for probing Brownian ratchet mechanisms, and essential research tools, providing a resource for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to understand or engineer bio-nanomachines.

The concept of Brownian motion in molecular machines pivots from viewing thermal noise as an obstacle to recognizing it as an exploitable resource. Machines at the molecular scale operate in a low-Reynolds-number regime where viscous forces dominate inertia. Directed motion cannot arise from simple reciprocal movements; instead, these machines employ mechanisms like Brownian ratchets, where thermal fluctuations are rectified by asymmetric, energy-driven potentials. This review examines how kinesin (intracellular transport), myosin (muscle contraction), ATP synthase (energy conversion), and CRISPR-Cas9 (DNA targeting) utilize this principle, highlighting shared biophysical themes.

Core Molecular Machines: Mechanisms and Quantitative Data

Kinesin-1: A Processive Linear Motor

Kinesin-1 is a dimeric motor protein that transports cargo along microtubules via a hand-over-hand walking mechanism. ATP hydrolysis in the leading head induces a conformational change that biases the thermal-driven search of the trailing head to the next binding site.

Table 1: Quantitative Biophysical Parameters of Featured Molecular Machines

| Parameter | Kinesin-1 | Myosin V | ATP Synthase (F₁) | CRISPR-Cas9 (S. pyogenes) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step Size | 8 nm (MT dimer spacing) | 36 nm (helical pitch on actin) | 120° rotation (γ subunit) | N/A (diffusive search) |

| Velocity | ~800 nm/s | ~300 nm/s | ~130 revolutions/s (at 100 µM ATP) | Kon ~0.5-5 µM⁻¹s⁻¹ (for target search) |

| Force Output | ~5-7 pN (stall force) | ~3 pN (stall force) | Torque ~40 pN·nm | N/A |

| Energy Source | ATP hydrolysis (~80-100 pN·nm) | ATP hydrolysis (~80-100 pN·nm) | Proton-motive force (Δp) & ATP | ATP (for Cas9 DNA unwinding) |

| Key Thermal Step | Diffusive search of tethered head | Lever-arm swing (power stroke) | Stochastic binding of protons to c-ring | 1D diffusion along DNA ("sliding") |

| Processivity | ~100 steps before detaching | ~20 steps before detaching | Continuous rotation | Binds target for hours once found |

Myosin V: A Cargo-Toting Stepper

Myosin V is a two-headed processive motor that moves along actin filaments. Its long lever arm amplifies small conformational changes in the catalytic core into a 36-nm step. Brownian motion facilitates the recovery stroke and the diffusive search of the trailing head for the next actin binding site.

ATP Synthase: A Rotary Nanogenerator

This machine couples proton flow down an electrochemical gradient (Δp) to the synthesis of ATP. The membrane-embedded F₀ subunit uses a Brownian ratchet mechanism: proton binding/dissociation to the c-ring applies a tangential force, biasing its thermal rotation. This drives the rotation of the γ-subunit in F₁, which catalyzes ATP formation via binding change mechanics.

CRISPR-Cas9: A Brownian-Search-Guided Nuclease

While not a motor protein, the CRISPR-Cas9 system exemplifies the critical role of Brownian motion in target localization. Cas9 locives its DNA target through a reduced-dimensionality search combining 3D diffusion and 1D sliding along the DNA duplex, dramatically accelerated by thermal fluctuations. Recognition is governed by stochastic DNA melting and RNA-DNA hybridization.

Experimental Protocols for Probing Brownian Mechanisms

Single-Molecule Fluorescence (FRET) for Kinesin/Myosin Stepping

Objective: To visualize the real-time, stochastic stepping dynamics of individual motor proteins. Methodology:

- Sample Preparation: Engineer a dimeric kinesin construct with specific cysteine residues for dye labeling. Label one head with a donor fluorophore (e.g., Cy3) and the other with an acceptor (e.g., Cy5) using maleimide chemistry.

- Surface Immobilization: Chemically immobilize microtubules or actin filaments on a passivated (PEG-biotin/streptavidin) glass surface in a flow chamber.

- Imaging: Introduce labeled motors and ATP into the chamber. Use a total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope with alternating-laser excitation to monitor FRET efficiency between heads in real time.

- Data Analysis: FRET efficiency changes indicate head movement. Step durations and intervals are analyzed to quantify the stochastic waiting times, fitting to models of thermally activated processes.

Single-Molecule Optical Trap Assay for Force Measurement

Objective: To measure the force output and step-wise progression of a single motor against an external load. Methodology:

- Bead-Motor Assembly: Tether a purified motor protein (e.g., kinesin) to a silica or polystyrene bead (~0.5-1 µm) via an antibody or direct linkage.

- Trap Setup: Capture the bead in a high-precision optical trap (laser focus) near a surface-immobilized filament (MT or actin).

- Force Feedback: As the motor walks, it pulls the bead from the trap center. A feedback system (e.g., acousto-optic deflector) moves the trap to maintain a constant force (force clamp) or position (position clamp).

- Analysis: Record bead displacement with nanometer precision. Under constant load, measure step size distributions and dwell-time kinetics to extract the load-dependent rate constants governing thermally assisted steps.

Magnetic Tweezers for ATP Synthase Rotation

Objective: To observe and manipulate the rotation of the F₀F₁-ATP synthase or its subcomplexes. Methodology:

- Protein Labeling: Engineer a His-tag on the static

aorbsubunit of F₀. Attach a magnetic bead (~1 µm) via anti-His antibodies. Alternatively, for F₁ alone, attach a fluorescent actin filament or gold nanoparticle to the γ-subunit. - Surface Tethering: Anchor the labeled enzyme to a glass coverslip in a flow cell.

- Rotation Induction & Measurement: Apply a rotating magnetic field to drive the bead (for F₀ studies, driven by proton flow or an applied field). For F₁, add ATP and observe the rotation of the actin filament under a fluorescence microscope.

- Data Extraction: Video analysis tracks bead/filament angle. Pause times between 120° substeps are analyzed as a function of [ATP] to reveal the stochastic binding kinetics driven by diffusion.

Single-Molecule DNA Curtains for CRISPR Target Search

Objective: To visualize the real-time 1D diffusion (sliding) of Cas9 along DNA during target search. Methodology:

- DNA Curtain Assembly: Use nanofabricated barriers on a lipid bilayer to align and stretch multiple λ-DNA molecules anchored at one end. Stain with YOYO-1 intercalating dye for visualization.

- Protein Labeling: Label Cas9 with a quantum dot (QD655) via a HaloTag or SNAP-tag system.

- Imaging: Inject labeled Cas9:sgRNA complex into the flow cell containing the DNA curtains. Image using TIRF microscopy with dual color (QD signal and DNA stain).

- Trajectory Analysis: Track the QD signal. Characterize binding events, differentiate between 1D sliding, hopping, and 3D dissociation by analyzing mean square displacement versus time.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 2: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Machine Studies

| Reagent/Material | Function/Application |

|---|---|

| PEG/Biotin-PEG Passivation Mix | Creates a non-fouling, functionalized surface on glass slides to immobilize filaments via streptavidin-biotin linkage, minimizing non-specific protein binding. |

| Streptavidin | Bridges biotinylated microtubules/actin filaments (or DNA for curtains) to the biotin-PEG surface. |

| Taxol (Paclitaxel) | Stabilizes polymerized microtubules, preventing depolymerization during kinesin motility assays. |

| ATPγS (Adenosine 5′-[γ-thio]triphosphate) | A slowly hydrolyzable ATP analog used to trap motor proteins in specific intermediate states for structural studies. |

| Cy3/Cy5 Maleimide | Thiol-reactive dyes for site-specific labeling of engineered cysteine residues in motor proteins for single-molecule FRET. |

| NeutrAvidin | Used as an alternative to streptavidin for surface anchoring; lacks glycosylation, reducing non-specific interactions. |

| Polymerase Chain Reaction (PCR) System | For generating long, biotin- or digoxigenin-labeled DNA substrates for optical trap or DNA curtain assays. |

| HaloTag Ligand (e.g., JF549) | A covalent, bright, and photostable fluorescent ligand for labeling HaloTag-fusion proteins like Cas9 for single-particle tracking. |

| Proteoliposome Preparation Kit | For reconstituting membrane proteins like ATP synthase F₀ subunit into defined lipid bilayers to study proton-driven rotation. |

| Oxygen Scavenging & Triplet State Quencher System (e.g., PCA/PCD, Trolox) | Essential for single-molecule fluorescence experiments to reduce photobleaching and blinking of fluorophores. |

Visualizing Mechanisms and Workflows

Title: Kinesin's Brownian Ratchet Stepping Cycle

Title: CRISPR-Cas9 Target Search via Facilitated Diffusion

Title: ATP Synthesis via a Brownian Rotary Ratchet

Molecular machines—proteins like kinesin, myosin, and ATP synthase—operate in a noisy, aqueous environment dominated by Brownian motion. The central thesis of this field posits that these nanoscale devices do not overpower thermal noise but instead harness it through conformational changes. Directed motion and mechanical work emerge from a sequence of stochastic fluctuations that are biased by chemical energy input (e.g., ATP hydrolysis) and potential landscapes shaped by molecular structure. This whitepaper details the mechanisms, experimental evidence, and methodologies underpinning this paradigm.

Core Physical Principles

The Fluctuation-Dissipation Theorem & Brownian Ratchets

At the core of the paradigm is the formal relationship between random thermal forces (fluctuations) and frictional drag (dissipation). For a particle with drag coefficient γ, the diffusion constant D is given by D = k_B T / γ (Einstein-Smoluchowski relation). A molecular machine is subject to these forces while existing in a multi-stable potential landscape. The introduction of an asymmetric, periodically fluctuating potential—a Brownian ratchet—can bias diffusion to produce net drift. The fundamental equation for particle flux in a flashing ratchet model is derived from the Fokker-Planck equation.

Energy Landscapes and Conformational Coordinates

Protein dynamics are described by a high-dimensional free energy landscape. Catalytic events (e.g., nucleotide binding/hydrolysis/release) systematically alter this landscape, lowering barriers between specific conformational states. Motion occurs via thermal kicks over these modulated barriers. The "power stroke" vs. "Brownian ratchet" debate has largely converged on a hybrid model: a sub-step of a conformational change may provide a directed impulse (power stroke), while the larger-scale search and docking are thermally driven.

Key Experimental Evidence & Quantitative Data

Single-Molecule Biophysics Studies

Advanced techniques have provided direct evidence for thermally driven motion.

Table 1: Key Single-Molecule Studies on Molecular Motors

| Motor Protein | Technique Used | Measured Step Size (nm) | Mean Dwell Time (ms) | Free Energy from ATP Hydrolysis (k_B T) | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesin-1 | Optical Tweezers | 8.2 ± 0.3 | 10-100 (load-dependent) | ~22 | [1] |

| Myosin V | FIONA* | 36 ± 5 (hand-over-hand) | 50-70 | ~20 | [2] |

| F₁-ATPase | High-Speed Imaging | 120° rotation substeps (90°, 30°) | < 1 ms per substep | ~20-30 per ATP | [3] |

| RNA Polymerase | Magnetic Tweezers | 0.34 nm (base pair) | Highly variable | N/A | [4] |

*FIONA: Fluorescence Imaging with One-Nanometer Accuracy.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol A: Single Kinesin Assay Using Optical Tweezers

- Objective: Measure step size, stall force, and ATP dependence of processive motion.

- Materials: See "Scientist's Toolkit" below.

- Method:

- A single kinesin molecule is biotinylated and attached to a streptavidin-coated polystyrene bead (0.5 μm diameter).

- The bead is captured in an optical trap and positioned over a microtubule immobilized on a coverslip.

- The trap stiffness is calibrated via power spectrum analysis of the bead's Brownian motion.

- Motility buffer (containing ATP, e.g., 1 mM) is introduced.

- The bead position is recorded at >10 kHz. Steps are identified using a change-point detection algorithm (e.g., hidden Markov modeling).

- Stall force is measured by increasing the trap's opposing load until forward motion ceases (typically ~5-7 pN for kinesin).

Protocol B: FRET-Based Conformational Change Detection

- Objective: Monitor real-time conformational dynamics of a protein (e.g., GTPase) in solution.

- Method:

- Engineer cysteine residues at two specific sites on the protein. Label with donor (Cy3) and acceptor (Cy5) fluorophores.

- Purify the dual-labeled protein.

- Load into a stopped-flow apparatus mixed with nucleotide (ATP/GTP) or partner protein.

- Excite the donor with a laser and monitor emission intensities of donor and acceptor simultaneously at high temporal resolution (μs-ms).

- Calculate FRET efficiency

E = I_A / (I_D + I_A). A time-dependent change in E reports on conformational distance changes. - Fit trajectories to kinetic models to extract rate constants for conformational transitions.

Visualization of Concepts and Pathways

Title: Core Paradigm of a Brownian Molecular Machine

Title: Single-Molecule Optical Trap Experimental Setup

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Reagents & Materials for Key Experiments

| Item | Function & Application | Example Product/Specification |

|---|---|---|

| Biotin-PEG-NHS Ester | Covalently links primary amines (lysines) on proteins to biotin for bead/tether attachment in force spectroscopy. | "EZ-Link NHS-PEG4-Biotin" (Thermo Fisher). Polyethylene glycol (PEG) spacer reduces non-specific surface interactions. |

| Streptavidin-Coated Polystyrene Beads | High-affinity linkage (biotin-streptavidin) for tethering biotinylated molecules in optical/magnetic tweezers. | 0.5-1.0 μm diameter, low fluorescence. (Spherotech, Polysciences). |

| Taxol-Stabilized Microtubules | Cytoskeletal track for kinesin/dynein motility assays. Polymerized from tubulin and stabilized with Taxol. | "Cytoskeleton Inc. Tubulin & MT Stabilization Kit". |

| ATPγS (Adenosine 5′-[γ-thio]triphosphate) | Slowly hydrolyzable ATP analog used to trap molecular motors in a pre-powerstroke state for structural studies. | Sodium salt, >95% pure (Roche, Sigma). |

| Cy3/Cy5 Maleimide Dyes | Thiol-reactive fluorophores for site-specific labeling of engineered cysteine residues in FRET experiments. | "GE Healthcare Cy3/5 Maleimide". Requires reducing agent-free buffers. |

| Passivation Mixture (PEG/BSA) | Coats glass surfaces (flow cells) to prevent non-specific adhesion of proteins and beads. | Mix of methoxy-PEG-silane and biotin-PEG-silane, followed by casein or BSA. |

| Oxygen Scavenging System | Reduces photobleaching and fluorophore blinking in single-molecule fluorescence assays. | "Gloxy" system: Glucose oxidase, catalase, and β-D-glucose in buffer. |

Implications for Drug Development

Understanding the conformational change paradigm is critical for rational drug design targeting molecular machines. Allosteric inhibitors can function by:

- Stabilizing a Non-Productive Conformation: Locking the protein in a state with a high barrier to thermal transition (e.g., kinase inhibitors).

- Disrupting the Energy Landscape Bias: Binding to alter the asymmetry of the potential, wasting thermal noise without productive output.

- Blocking State Transitions Required for Ratcheting: Preventing the specific conformational change that makes the Brownian search directional.

High-resolution dynamics data (from FRET, cryo-EM, MD simulation) are used to identify these cryptic allosteric sites, moving beyond static structure-based design.

This whitepaper examines the biophysical determinants of stochastic, Brownian forces in cellular environments, framing their modulation within the broader thesis of molecular machines research. The efficient operation of molecular machines—from polymerases to chaperones—is governed by a balance between deterministic chemical potential and the stochastic buffeting of the thermal bath. Two key, interlinked physicochemical parameters of this bath are solvent viscosity and macromolecular crowding. This guide details their quantitative impact, measurement protocols, and implications for in vitro experimentation and in silico modeling in drug development.

Core Biophysical Principles

2.1 The Modified Langevin Equation

In a crowded cellular milieu, the classic Langevin equation for a diffusing particle is modified to account for non-Newtonian and viscoelastic effects:

m dv/dt = -ζ v + F_R(t) + F_ext

where the friction coefficient ζ is no longer simply 6πηr (Stokes' law) but a complex function of time and local crowder concentration. The random force F_R(t)'s magnitude is also scaled by the effective damping.

2.2 Key Quantitative Impacts The following table summarizes the directional effects of increasing solvent viscosity and crowder concentration on system parameters.

Table 1: Quantitative Effects of Viscosity and Crowding on Stochastic Forces

| Parameter | Effect of Increased Solvent Viscosity (Newtonian) | Effect of Increased Macromolecular Crowding (Non-Newtonian) | Typical Experimental Range (Cytosol-like) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Coefficient (D) | Decreases proportionally (D ∝ 1/η) | Decreases non-linearly; may exhibit anomalous sub-diffusion | 10-50% of dilute buffer value |

| Reaction Rate (Diffusion-Limited) | Decreases proportionally | Decreases or increases (via excluded volume effect) | Variation: -90% to +500% |

| Effective Stochastic Force ( |

Increases (fluctuation-dissipation) | Complex; depends on timescale & crowder dynamics | Magnitude scaled by effective ζ |

| System Viscosity (η_eff) | Increases linearly | Increases exponentially with crowder volume fraction (φ) | η_eff ≈ 1-10 cP (vs. water ~0.9 cP) |

| Friction Coefficient (ζ) | Increases linearly (ζ = 6πηr) | Increases non-linearly; memory effects possible | 2-10x dilute value |

Experimental Protocols

3.1 Protocol: Measuring Macromolecular Diffusion via FRAP

- Objective: Quantify the effective diffusion coefficient (D_eff) of a labeled probe (e.g., GFP, 70 kDa dextran) in crowded buffers.

- Reagents: Fluorescent probe, crowding agents (Ficoll PM400, PEG 8000, BSA), assay buffer.

- Procedure:

- Prepare samples with varying crowder types (inert/polymer vs. protein) and volume fractions (φ = 0-0.3).

- Load into glass-bottom dishes or capillary tubes.

- Using a confocal microscope, define a region of interest (ROI) and bleach with high-intensity laser.

- Monitor fluorescence recovery at low laser intensity. Fit recovery curve to appropriate model (e.g., anomalous diffusion:

I(t) = I_final - ΔI * exp(-(t/τ)^β)) whereβ=1for normal,<1for anomalous diffusion. - Calculate

D_eff = (ω²)/(4τ)for normal diffusion (ω is ROI radius).

3.2 Protocol: Quantifying Viscosity Effects on Enzyme Kinetics using Stopped-Flow

- Objective: Measure the change in catalytic rate constant (k_cat) of a model enzyme with solvent viscosity.

- Reagents: Enzyme (e.g., Lysozyme), substrate, viscosity modulators (sucrose, glycerol).

- Procedure:

- Prepare matched substrate/enzyme solutions in buffers containing 0-40% w/v sucrose. Measure bulk viscosity with a microviscometer.

- Load enzyme and substrate solutions into a stopped-flow apparatus.

- Rapidly mix and monitor product formation (via absorbance/fluorescence).

- Fit time traces to obtain observed rate constants (k_obs).

- Plot

1/k_obsvs. solvent viscosity (Kramers' theory). The slope informs on the degree of solvent coupling in the rate-limiting step.

Visualization of Concepts and Workflows

Diagram Title: Stochastic Force Modulation Pathway

Diagram Title: FRAP Experimental Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials for Viscosity and Crowding Studies

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Ficoll PM70/400 | Inert, highly branched polysaccharide crowder. Mimics steric (excluded volume) effects without specific interactions. Used to probe physical crowding. |

| PEG (various MW) | Linear polymer crowder. Induces both steric crowding and weak attractive interactions (depletion forces). Useful for testing polymer-mesh effects. |

| BSA or Cytosol Mimics | Protein-based crowders. Provide a more biologically relevant, interacting crowder background. Commercial "cell lysates" offer complex mimicry. |

| Sucrose/Glycerol | Small molecule viscosity modulators. Increase solvent viscosity (η) linearly with concentration in a Newtonian manner, without significant crowding. |

| Fluorescent Nanobeads (20-100nm) | Inert tracer particles for single-particle tracking (SPT) or microrheology to map local viscosity and viscoelasticity. |

| FRET-capable Fluorophore Pairs | For measuring intra- or intermolecular distances via Förster Resonance Energy Transfer. Sensitive to crowding-induced conformational shifts. |

| Microfluidic Laminar-Flow Viscosimeter | Device for precise, small-volume (µL) measurement of sample-specific bulk viscosity against standards. |

| Monte Carlo/BD Simulation Software (e.g., HADDOCK, BioSimSoft) | In silico tools for modeling Brownian dynamics in user-defined crowded environments. Validates and predicts experimental outcomes. |

Capturing the Random Walk: Cutting-Edge Methods to Measure and Model Stochastic Machine Dynamics

This technical guide details the application of three pivotal single-molecule techniques—single-molecule Förster Resonance Energy Transfer (smFRET), Optical Tweezers, and Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM)—for the analysis of real-time fluctuations in molecular machines. Framed within a broader thesis on Brownian motion, we examine how these tools dissect the stochastic, thermally driven motions that are fundamental to biomolecular function, conformational dynamics, and mechanochemical coupling. The insights are critical for researchers and drug development professionals aiming to modulate molecular machine activity.

The Role of Brownian Motion in Molecular Machines

Brownian motion, the random thermal agitation of particles in a fluid, is not merely background noise but the principal driver of conformational sampling in molecular machines. These machines, such as helicases, ribosomes, and motor proteins, harness this stochasticity to perform work through mechanisms like Brownian ratchets and power strokes. Single-molecule techniques are uniquely capable of resolving these nanoscale fluctuations, providing direct observation of non-equilibrium states and transient intermediates invisible to ensemble averages.

Technique 1: Single-Molecule FRET (smFRET)

Core Principle & Application to Fluctuation Analysis

smFRET measures nanoscale distance changes (typically 2-10 nm) between a donor and an acceptor fluorophore attached to a biomolecule. Fluctuations in FRET efficiency report on conformational dynamics in real time, allowing the observation of Brownian-driven transitions between states.

Key Experimental Protocol: smFRET for a Nucleic Acid Helicase

- Sample Preparation: Engineer a dual-labeled DNA substrate with Cy3 (donor) at one end and Cy5 (acceptor) at the other. Purify the helicase of interest.

- Surface Immobilization: Passivate a quartz microscope slide with a PEG-biotin coating. Immobilize streptavidin, then biotinylated DNA constructs.

- Data Acquisition: Use a total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope. Image donor and acceptor emission channels simultaneously at 10-100 ms temporal resolution.

- Fluctuation Analysis: Extract FRET time traces. Use hidden Markov modeling (HMM) or change-point analysis to identify discrete states. Calculate transition rates and dwell times. Analyze correlation functions to detect sub-millisecond dynamics and conformational disorder.

Diagram Title: smFRET Experimental Workflow

Table 1: Representative smFRET Metrics for a Model Helicase

| Parameter | Value Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| FRET Efficiency (Low State) | 0.2 - 0.3 | Open/DNA-bound conformation |

| FRET Efficiency (High State) | 0.7 - 0.8 | Closed/translocating conformation |

| Dwell Time in Low State | 500 ± 150 ms | Duration of substrate engagement |

| Dwell Time in High State | 100 ± 40 ms | Duration of power stroke |

| Transition Rate (Low→High) | 2.0 ± 0.5 s⁻¹ | ATP-binding coupled step |

| Transition Rate (High→Low) | 10.0 ± 2.0 s⁻¹ | Rate-limiting release step |

Technique 2: Optical Tweezers

Core Principle & Application to Fluctuation Analysis

Optical tweezers use a highly focused laser beam to trap dielectric microspheres, applying piconewton forces and measuring nanometer displacements. They directly probe the forces and displacements generated by molecular machines, resolving the Brownian fluctuations that reveal mechanical compliance, energy landscapes, and intermediate states.

Key Experimental Protocol: High-Resolution Trapping for a Molecular Motor

- Assembly: Tether a single kinesin motor between two polystyrene beads via complementary DNA handles. One bead is held in a micropipette, the other in the optical trap.

- Force Feedback: Employ a passive (fixed trap) or active (force feedback) mode. For fluctuation analysis, often operate in the "force clamp" mode, maintaining constant force on the motor.

- Data Collection: Record bead position at >10 kHz bandwidth. As the motor steps, the tether length changes. Record the displacement trace under constant assisting or hindering load.

- Fluctuation Analysis: Analyze variance and autocorrelation of position within a single dwell to measure the trap stiffness and the system's thermal motion. Step-finding algorithms (e.g., k-VGF) identify substeps. Fluctuation-dissipation theorems can be applied to extract energy landscape parameters.

Diagram Title: Optical Tweezers Core System

Table 2: Typical Optical Tweezers Data for Kinesin-1

| Parameter | Value Range | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Step Size | 8.2 ± 0.3 nm | Microtubule dimer spacing |

| Stall Force | 5 - 7 pN | Maximum load motor can oppose |

| Dwell Time Variance (at 1 pN load) | 15 - 25 nm² | Brownian motion within the pre-powerstroke state |

| Substep Size (Biochemical) | 2 - 4 nm | Brownian search preceding head binding |

| Trap Stiffness (Typical) | 0.02 - 0.1 pN/nm | Determines spatial resolution |

| Displacement Resolution (BW 10 kHz) | 0.1 - 0.3 nm (rms) | Limits detection of small fluctuations |

Technique 3: Cryo-Electron Microscopy (Cryo-EM)

Core Principle & Application to Fluctuation Analysis

Cryo-EM images flash-frozen, vitrified samples to capture molecules in near-native states. While not a real-time technique, its power lies in visualizing structural heterogeneity—the "frozen" snapshots of Brownian motion—allowing classification of multiple conformations from a single sample.

Key Experimental Protocol: Single-Particle Analysis for a Ribosome

- Vitrification: Apply purified ribosome sample (in a functional buffer) to an EM grid. Blot and plunge-freeze in liquid ethane.

- Data Collection: Use a 300 keV cryo-electron microscope with a direct electron detector. Acquire thousands of movies under low-dose conditions (~40 e⁻/Ų).

- Image Processing: Perform motion correction and CTF estimation. Pick millions of particle images.

- Heterogeneity Analysis: Use 2D and 3D classification to separate particles into distinct conformational classes (e.g., ratcheted vs. non-ratcheted, tRNA-bound states). Refine each class to high resolution. Analyze populations to infer free energy landscapes and transition pathways.

Diagram Title: Cryo-EM Heterogeneity Analysis Pipeline

Table 3: Cryo-EM Analysis of a Translating Ribosome

| Parameter | Value / Outcome | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|

| Total Particles Initially Extracted | ~2,000,000 | Statistical basis for classification |

| Major Conformational Classes Identified | 5-7 (e.g., Classical, Ratcheted, Hybrid) | Discrete states in the Brownian trajectory |

| Population of Dominant State | 45% ± 5% | Relative stability of the intermediate |

| Local Resolution Range (in a map) | 2.8 - 4.5 Å | Defines interpretability of regions |

| Inter-class Distance (Rotational) | 3° - 10° (Ratcheting) | Magnitude of Brownian-driven motion |

| Estimated Free Energy Difference (ΔG) between States | 1 - 3 kT | Calculated from population ratios |

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Essential Materials for Single-Molecule Fluctuation Studies

| Item | Function | Example/Notes |

|---|---|---|

| PEG-Passivated Slides/Coverslips | Minimizes non-specific binding of biomolecules to surfaces, crucial for isolating single molecules. | Mixture of mPEG and biotin-PEG for TIRF microscopy. |

| Streptavidin / NeutrAvidin | High-affinity bridge for immobilizing biotinylated molecules (DNA, proteins). | Used in smFRET and optical tweezer tethering. |

| Fluorophores for smFRET | Donor-acceptor pair with spectral overlap. Must be photostable. | Cy3/Cy5, Alexa Fluor 555/647, or newer self-healing dyes like Cy3B/ATTO 647N. |

| Functionalized Microspheres | Handles for optical tweezer manipulation. | Polystyrene or silica beads coated with streptavidin or epoxy groups. |

| DNA/RNA Handle Constructs | Defined-length spacers to tether molecules without interfering with function. | Typically dsDNA of 500-2000 bp with end modifications (biotin, digoxigenin). |

| Oxygen Scavenging System | Reduces photobleaching and blinking in fluorescence studies. | Protocatechuic acid (PCA) / Protocatechuate-3,4-dioxygenase (PCD) or Trolox. |

| Cryo-EM Grids | Supports the vitrified sample for electron microscopy. | Holey carbon grids (e.g., Quantifoil, C-flat) often glow-discharged before use. |

| Vitrification Device | Rapidly freezes aqueous samples into amorphous ice. | Manual plunge freezer or automated device (e.g., Vitrobot, CP3). |

Integrating smFRET, optical tweezers, and cryo-EM provides a multi-scale framework for analyzing Brownian motion in molecular machines. smFRET offers ultra-fast (<1 ms) conformational reporting, optical tweezers directly measure forces and displacements from thermal fluctuations, and cryo-EM statistically maps the structural landscape sampled by Brownian dynamics. Together, they transform our understanding of stochasticity from a nuisance into a quantifiable, fundamental property governing molecular mechanism—a critical perspective for rational drug design targeting dynamic biomolecules.

The operation of biological molecular machines—such as ATP synthase, kinesin, and the ribosome—is fundamentally governed by Brownian motion. Within the thermal bath of the cell, these nanoscale devices harness random thermal fluctuations to perform directed work, a process described by the principles of stochastic thermodynamics. This whitepaper, framed within a broader thesis on Brownian motion in molecular machines research, provides an in-depth technical guide to simulating their "machine cycles" using Molecular Dynamics (MD) and Brownian Dynamics (BD) simulations. These computational frontiers offer unique insights into the mechanochemical coupling, free energy landscapes, and kinetic pathways that define function, with direct implications for understanding disease mechanisms and rational drug design.

Foundational Theory and Simulation Hierarchy

MD simulations solve Newton's equations of motion for all atoms, providing high-resolution temporal and spatial data. The core equation is: Fi = mi ai = -∇i U(r^N) where ( U(r^N) ) is the potential energy of the system described by a molecular mechanics force field.

BD simulations coarse-grain the system, treating solvent implicitly and propagating particles using the Langevin equation: mi dvi/dt = -∇i U(r^N) - γi vi + ξi(t) where ( γi ) is the friction coefficient and ( ξi(t) ) is a stochastic force satisfying the fluctuation-dissipation theorem, ( ⟨ξi(t)·ξj(t')⟩ = 2γi kB T δ_{ij} δ(t-t') ).

The choice between methods involves a trade-off between resolution and accessible timescales, as summarized below.

Table 1: Comparison of MD and BD for Molecular Machine Simulations

| Parameter | All-Atom Molecular Dynamics (MD) | Brownian Dynamics (BD) |

|---|---|---|

| Spatial Resolution | Atomic (0.1 Å) | Coarse-grained (≥ 10 Å) |

| Temporal Resolution | Femtoseconds (10⁻¹⁵ s) | Nanoseconds to microseconds (10⁻⁹–10⁻⁶ s) |

| Typical System Size | 10⁴ – 10⁶ atoms | 10 – 10³ coarse-grained particles |

| Explicit Solvent? | Yes | No (Implicit) |

| Key Output | Atomistic trajectories, detailed bonding | Diffusion-limited rates, large-scale conformational changes |

| Primary Computational Cost | Force field calculations per time step | Solving stochastic differential equations |

| Ideal for Studying | Chemical catalysis, ion pumping, allosteric communication | Large-scale conformational transitions, diffusional encounter, motor stepping |

Core Methodologies and Experimental Protocols

Molecular Dynamics Protocol for ATPase Cycle Analysis

This protocol outlines steps to simulate the hydrolysis cycle of a motor protein like kinesin.

System Preparation:

- Obtain starting coordinates (e.g., PDB ID: 3KIN for kinesin).

- Use

pdb2gmx(GROMACS) ortleap(AMBER) to add missing hydrogens, assign protonation states, and parameterize the system with a force field (e.g., CHARMM36 or AMBERff19SB). - Embed the protein in an explicit solvent box (e.g., TIP3P water) with dimensions ≥ 10 Å from the protein.

- Add ions (e.g., Na⁺, Cl⁻) to neutralize charge and achieve physiological concentration (e.g., 150 mM).

Energy Minimization and Equilibration:

- Minimize energy using steepest descent or conjugate gradient algorithm for 5,000-50,000 steps to remove steric clashes.

- Perform NVT equilibration for 100 ps, restraining protein heavy atoms (force constant 1000 kJ/mol/nm²), heating system to 310 K using a thermostat (e.g., V-rescale).

- Perform NPT equilibration for 200 ps, with same restraints, to adjust pressure to 1 bar using a barostat (e.g., Parrinello-Rahman).

Production MD and Enhanced Sampling:

- Release restraints and run unbiased production MD for 100 ns – 1 µs, saving coordinates every 10-100 ps.

- For sampling the hydrolysis cycle, employ enhanced sampling:

- Umbrella Sampling: Define a reaction coordinate (e.g., distance between γ-phosphate of ATP and catalytic water). Run a series of windows with harmonic restraints (force constant 300-1000 kJ/mol/nm²) along the coordinate. Use WHAM to construct the potential of mean force (PMF).

- Gaussian Accelerated MD (GaMD): Add a harmonic boost potential to smoothen the energy landscape, enabling longer-timescale events like ADP/Pi release.

Analysis:

- Calculate Root Mean Square Deviation (RMSD) to assess stability.

- Use Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to identify dominant collective motions.

- Compute free energy profiles (PMFs) from umbrella sampling.

Brownian Dynamics Protocol for Ribosome Subunit Association

This protocol simulates the diffusion-driven association of ribosomal subunits.

Coarse-Grained Model Preparation:

- Represent the 30S and 50S ribosomal subunits as rigid bodies composed of overlapping spheres (one sphere per 5-10 residues). Assign each sphere a hydrodynamic radius.

- Define interaction surfaces and attractive potentials based on electrostatic complementarity (using Poisson-Boltzmann-derived charges) and knowledge-based potentials.

BD Simulation Execution:

- Integrate the overdamped Langevin equation (neglecting inertia) using the Ermak-McCammon algorithm: ri(t+Δt) = ri(t) + (Di/kB T) Fi Δt + Ri(Δt) where ( Ri ) is a random displacement with variance ( ⟨Ri²⟩ = 2D_iΔt ).

- Use a large simulation box (≥ 200 nm side length) with periodic boundary conditions.

- Place subunits at a center-to-center distance > 50 nm.

- Use a time step (Δt) of 10-50 ps. Run 10⁶ – 10⁸ steps to observe multiple association-dissociation events.

Analysis:

- Calculate the radial pair distribution function ( g(r) ) between subunit centers of mass.

- Determine the association rate constant ( k_{on} ) from the slope of the number of bound complexes versus time.

- Identify successful encounter complexes and analyze their interfacial geometry.

Visualization of Workflows and Pathways

Diagram 1: MD/BD Simulation Decision Workflow

Diagram 2: Kinesin Mechanochemical Cycle

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools and Resources

| Tool/Resource | Type/Category | Primary Function in Simulation |

|---|---|---|

| GROMACS | MD Simulation Software | High-performance engine for running all-atom and coarse-grained MD; excels in biomolecular systems. |

| AMBER | MD Simulation Suite | Provides force fields (ff19SB) and tools for simulating proteins, nucleic acids, and drug-like molecules. |

| CHARMM-GUI | Web-based Input Generator | Creates ready-to-run simulation input files for various MD packages from a PDB structure. |

| NAMD | MD Simulation Software | Scalable, parallel MD designed for large biomolecular systems on high-performance computing clusters. |

| OpenMM | MD Library & API | A flexible, GPU-accelerated toolkit for running MD simulations, often accessed via Python scripts. |

| BioSimSpace | Interoperability Platform | Facilitates the setup, execution, and analysis of simulations across different MD software packages. |

| PLUMED | Enhanced Sampling Plugin | A library for adding advanced sampling methods (metadynamics, umbrella sampling) to MD simulations. |

| SOFTWARE_NAME | BD Simulation Package | Specialized for Brownian Dynamics simulations of macromolecular association and diffusion. |

| AlphaFold2 DB | Structural Database | Source of high-accuracy predicted protein structures for systems lacking experimental coordinates. |

| CHARMM36m | Molecular Force Field | A state-of-the-art all-atom force field for proteins, providing accurate dynamics and folding properties. |

| Martini 3 | Coarse-Grained Force Field | Enables larger-scale and longer-timescale simulations by representing groups of atoms as single beads. |

| VMD | Visualization & Analysis | For rendering molecular trajectories, creating publication-quality images, and basic trajectory analysis. |

| MDTraj | Analysis Library (Python) | A fast, flexible Python library for analyzing MD trajectories, enabling custom analysis scripts. |

This whitepaper, framed within the broader thesis on Brownian motion in molecular machines research, provides an in-depth analysis of the Brownian Ratchet mechanism as applied to polymerase translocation and proofreading. The mechanism, fundamentally reliant on thermal fluctuations, is a cornerstone for understanding fidelity in replication and transcription, with direct implications for drug development targeting these processes.

Core Mechanism and Theoretical Framework

The Brownian Ratchet postulates that directional motion or selective action is achieved not by a power stroke, but by rectifying unbiased thermal (Brownian) motion through asymmetric energy potentials or kinetic gating. In nucleic acid polymerases, this manifests in two key phases:

- Translocation: The post-chemistry shift of the polymerase along the template, moving the nascent base pair from the insertion (A) site to the post-insertion (P) site, is driven by thermal fluctuations and then biased by nucleotide binding.

- Proofreading: During editing, the mispaired primer terminus undergoes thermal fraying and Brownian motion between the polymerase active site and a separate exonuclease site. Selective excision is achieved by kinetic gating that favors partitioning of mismatched DNA into the exonuclease site.

This mechanism is inherently energy-efficient, coupling chemical energy (from NTP hydrolysis or phosphodiester bond formation) to set the ratchet rather than directly drive motion.

Experimental Methodologies for Analysis

Single-Molecule FRET (smFRET) to Monitor Translocation

Objective: To observe real-time, stochastic translocation dynamics of polymerases. Protocol:

- Sample Preparation: Label the polymerase with a donor fluorophore (e.g., Cy3) and the DNA template at a specific downstream position with an acceptor fluorophore (e.g., Cy5).

- Immobilization: Biotinylate the DNA or polymerase and tether it to a neutravidin-coated quartz microscope slide or coverslip within a flow chamber.

- Imaging: Use a total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscope to excite donor fluorophores. Monitor emission intensities of donor (ID) and acceptor (IA) over time.

- Data Acquisition & Analysis: Calculate FRET efficiency (E = IA / (ID + I_A)). A stepwise change in E corresponds to a discrete translocation event. Dwell times between steps are analyzed to determine kinetics. Conduct experiments in the presence of natural substrates (NTPs), non-hydrolyzable analogs (e.g., AMPPNP), or inhibitors.

- Controls: Perform experiments with inactive polymerase mutants (e.g., Klenow Fragment exo-) to isolate translocation from proofreading.

Pre-Steady-State Kinetic Analysis of Proofreading

Objective: To quantify the partitioning efficiency between polymerase and exonuclease sites. Protocol:

- Rapid Chemical Quench-Flow:

- Step 1 (Extension): Mix a pre-annealed radiolabeled (³²P) DNA primer/template with a single-nucleotide mismatch at the 3'-end with polymerase in one syringe. Rapidly mix with a solution containing the correct dNTP in a second syringe.

- Step 2 (Varying Delay): Allow the reaction to proceed for a variable time (ms to s) before quenching with 0.5 M EDTA.

- Step 3 (Analysis): Resolve products on denaturing polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (PAGE). Quantify bands corresponding to extended product (n+1) and excision product (n-1) using phosphorimaging.

- Partitioning Calculation: The fraction of mismatches excised (fexo) is determined from the ratio of excision product to total product. The reciprocal of the partition ratio (fpol / f_exo) defines the proofreading efficiency. Measurements are repeated for matched and mismatched termini.

- Inhibitor Studies: Repeat in the presence of exonuclease-site inhibitors (e.g., phosphonoformic acid) or translocation-blocking drugs to dissect contributions.

Key Quantitative Data and Findings

Table 1: Representative Kinetic Parameters for Brownian Ratchet Processes in Model Polymerases

| Parameter | T7 DNA Polymerase (Matched) | T7 DNA Polymerase (Mismatched) | E. coli RNA Polymerase | Notes / Reference |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Translocation Dwell Time (ms) | 2 - 5 ms | N/A | 20 - 50 ms | Measured via smFRET; varies with template sequence. |

| Forward Translocation Rate (s⁻¹) | ~250 s⁻¹ | N/A | ~25 s⁻¹ | Governed by thermal fluctuation & NTP binding affinity. |

| Partitioning to Exonuclease Site (f_exo) | < 0.001 | 0.1 - 0.9 | N/A (lacks exo site) | Highly mismatch-dependent; defines proofreading specificity. |

| Excision Rate (s⁻¹) | < 0.001 s⁻¹ | 1 - 100 s⁻¹ | N/A | Can exceed polymerization rate for severe mismatches. |

| Energy Source for Ratcheting | dNTP binding energy | Pyrophosphate release / dNTP binding | NTP binding energy | Sets bias for forward translocation. |

Table 2: Impact of Pharmacological Interventions on Ratchet Mechanisms

| Intervention / Drug | Target Process | Observed Effect on Translocation | Observed Effect on Proofreading | Potential Therapeutic Context |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Non-hydrolyzable NTP analogs (AMPPNP) | NTP Binding | Arrests translocation; traps pre-translocation state. | Inhibits by preventing progression to exo-site competent state. | Antiviral (polymerase studies). |

| Acyclovir (triphosphate form) | Chain Termination | Terminates chain; prevents translocation post-incorporation. | Alters partitioning dynamics for terminated primer. | Herpesvirus therapy. |

| Phosphonoformic Acid (PFA) | Pyrophosphate Analog | Slows pyrophosphate release, reducing bias for forward step. | May increase excision by stabilizing pre-translocation state. | Broad-spectrum antiviral. |

| α-amanitin | RNA Pol II Bridge Helix | Increases backtracking, disrupts forward ratchet. | N/A (eukaryotic RNAP lacks intrinsic exo). | Research toxin; probes translocation. |

Visualization of Mechanisms and Workflows

Diagram 1: Polymerase Translocation as a Brownian Ratchet

Diagram 2: Proofreading via Kinetic Partitioning

Diagram 3: smFRET Workflow for Translocation

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

| Reagent / Material | Function in Analysis | Key Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| Non-hydrolyzable NTP Analogs (e.g., AMPPNP, GMPPNP) | Trap pre-translocation state; dissect the role of binding vs. hydrolysis in ratcheting. | Purity is critical to avoid trace NTP contamination driving catalysis. |

| Biotinylated DNA Oligonucleotides | For surface immobilization in single-molecule assays (smFRET, optical traps). | Position of biotin (template vs. primer end) affects complex orientation and mechanics. |

| Site-Specific Labeling Dyes (Cy3, Cy5, Alexa Fluor series) | Donor-acceptor pair for smFRET to monitor distance changes during translocation. | Labeling efficiency and photostability directly impact data quality and duration. |

| Neutravidin-Coated Flow Cells/Surfaces | Provide high-affinity, stable binding for biotinylated complexes in single-molecule imaging. | Passivation (e.g., with PEG) is essential to minimize non-specific surface interactions. |

| Rapid Chemical Quench-Flow Instrument | To measure pre-steady-state kinetics of polymerization and excision on millisecond timescales. | Dead time of the instrument limits observation of the fastest kinetic steps. |

| ³²P or Fluorescently-labeled dNTPs/NTPs | Enable sensitive detection of primer extension and excision products in bulk kinetics gels. | Specific activity/labeling must be consistent for quantitative comparison across experiments. |

| Exonuclease-Deficient Polymerase Mutants (e.g., Klenow exo-) | Control to isolate translocation and polymerization kinetics from proofreading activity. | Ensure the mutation does not inadvertently alter polymerization rates or processivity. |

Within the broader thesis on Brownian motion in molecular machines, a central challenge is to quantitatively distinguish passive thermal diffusion from active, chemically driven power strokes. This guide presents a rigorous experimental framework for decoupling these forces, which is critical for elucidating the mechanochemical coupling efficiency in systems like kinesin, myosin, and F1F0-ATP synthase, with direct implications for targeted drug development.

Molecular machines operate in a regime dominated by thermal noise. The "Brownian ratchet" paradigm posits that these machines bias random thermal motions to perform directed work. The active power stroke—a conformational change driven by ATP hydrolysis or ion flux—imposes directionality. Disentangling the stochastic from the deterministic is essential for measuring true thermodynamic efficiency and identifying pathological dysfunction.

Theoretical Foundations & Quantifiable Parameters

The motion of a molecular machine along its track can be modeled as a combination of a diffusive process and a deterministic drift.

Table 1: Key Parameters for Decoupling Diffusion and Power Strokes

| Parameter | Symbol | Description | Experimental Access Method |

|---|---|---|---|

| Diffusion Coefficient | D | Measures variance in position due to thermal motion. | Mean Square Displacement (MSD) analysis in absence of ATP. |

| Drift Velocity (Active) | v | Average velocity from directed power strokes. | Mean displacement over time in presence of ATP. |

| Stall Force | F_s | External load at which net velocity is zero. | Optical tweezers or resistive load assay. |

| Dispersion | σ² | Variance in position over time during active motion. | Variance from trajectory ensemble during ATP-driven motion. |

| Peclet Number | Pe = vL/D | Ratio of convective (active) to diffusive transport rates. | Calculated from measured v and D; Pe >> 1 indicates active dominance. |

| Step Ratio | R_step | (Observed step rate) / (Theoretical diffusive encounter rate). | Single-molecule stepping assay vs. model. |

Core Experimental Methodologies

Single-Molecule Fluorescence with Zero-ATP Controls

Protocol: Utilize Total Internal Reflection Fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy to image individual fluorescently labeled motors (e.g., Cy3-labeled kinesin) moving on immobilized microtubules.

- Active Condition: Image in imaging buffer containing 2 mM ATP, 50 mM KCl, 1 mM MgCl2, oxygen scavenger system (0.5% w/v glucose, 1 mg/mL glucose oxidase, 0.04 mg/mL catalase), and triplet state quencher (1 mM Trolox).

- Diffusion-Only Control: Replace ATP with 5 mM ADP or Apyrase (2 U/mL) to hydrolyze any trace ATP. Alternatively, use a non-hydrolyzable ATP analog (AMP-PNP, 5 mM).

- Data Acquisition: Record 30-second videos at 100 fps. Track centroid positions with sub-pixel localization (e.g., using TrackPy or uTrack).

- Analysis: For the -ATP condition, calculate the Mean Square Displacement (MSD) vs. time lag (τ): MSD(τ) = 2Dτ. Fit to obtain D. For the +ATP condition, calculate the ensemble-averaged velocity (v) from linear fit of mean displacement vs. time. Calculate the variance (σ²) of displacement at each τ.

Table 2: Expected Results for Kinesin-1

| Condition | D (μm²/s) | v (nm/s) | σ² at τ=1s (nm²) | Conclusion |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| +ATP (2 mM) | ~0.004 | 800 ± 50 | ~6400 | Directed motion with minor dispersion. |

| +AMP-PNP (5 mM) | 0.03 ± 0.01 | 0 | ~60,000 | Free diffusion, weakly bound state. |

| +ADP (5 mM) | 0.02 ± 0.005 | 0 | ~40,000 | Free diffusion, different weak binding. |

High-Precision Optical Trap with Load Dependency

Protocol: Use a dual-beam optical trap to capture a single dielectric bead attached to a single molecular motor. The trap acts as a linear spring, applying a defined load.

- System Setup: Trap a 1 μm silica bead coated with streptavidin, attached to a biotinylated motor (e.g., myosin V). Interact with an actin filament suspended between two pedestals.

- Diffusion Measurement: In the absence of ATP, record the bead's positional fluctuations within the trap. The variance of the position (⟨x²⟩) gives the trap stiffness κ via the Equipartition Theorem: (1/2)κ⟨x²⟩ = (1/2)k_BT.

- Active Motion under Load: With ATP present, measure velocity (v) as a function of opposing load (F = κ * displacement). Plot v(F) to extrapolate the stall force (F_s).

- Decoupling Analysis: The effective diffusion coefficient Deff(F) during active motion can be measured from variance around mean displacement. Compare Deff to the baseline D from step 2. A constant Deff ≈ D suggests a pure power stroke; a load-dependent Deff suggests a biased diffusion mechanism.

Single-Molecule FRET to Probe Conformational States

Protocol: Use smFRET to monitor sub-steps of the power stroke independently from translational diffusion.

- Labeling: Engineer a double-cysteine mutant of the motor's lever arm or nucleotide-binding domain. Label with donor (Cy3) and acceptor (Cy5) dyes.

- Measurement: Under TIRF, observe FRET efficiency (E_FRET) time traces under three conditions: no nucleotide, ADP, and ATPγS (slowly hydrolyzable).

- Correlation: Synchronize FRET state transitions (indicative of conformational "strokes") with translational stepping events observed via bead or label tracking. A tight correlation indicates a direct, deterministic power stroke. A loose correlation suggests a diffusive search limited by the conformational change.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Materials for Decoupling Experiments

| Item | Function & Rationale |

|---|---|

| Non-hydrolyzable ATP analogs (AMP-PNP, ATPγS) | To lock motors in pre- or post-power stroke states without enabling turnover, isolating diffusive behavior. |

| Oxygen Scavenger System (GlOx/Catalase) | Prolongs fluorophore lifetime and prevents photodamage, essential for single-molecule observation. |

| Triplet State Quencher (Trolox) | Reduces dye blinking, providing continuous trajectories for accurate MSD analysis. |

| PEG Passivation Reagents | Passivates flow chamber surfaces to prevent non-specific motor or filament adhesion, reducing noise. |

| Biotin-PEG-NHS Ester | Functionalizes coverslips for specific immobilization of streptavidin-coated beads or biotinylated filaments. |

| Apyrase | Enzyme that rapidly depletes ambient ATP to sub-nanomolar levels, creating strict no-ATP controls. |

| Microtubule/Actin Stabilizing Agents (Taxol, Phalloidin) | Maintains cytoskeletal track integrity over long experimental timescales. |

| Zero-Mode Waveguides (ZMWs) | Nano-structures that enable observation of single-molecule fluorescence at physiological, high (mM) ATP concentrations. |

Data Interpretation & Causal Diagrams

Diagram 1: Integrated experimental workflow for decoupling forces.

Diagram 2: Decision logic for interpreting mechanism from data.

The precise decoupling of thermal diffusion from active power strokes is not merely a technical challenge but a foundational requirement for advancing the thesis on Brownian motion in molecular machines. The integrated experimental matrix presented here—combining zero-ATP controls, load-dependent kinetics, and conformational sensing—provides a robust framework to assign quantitative weights to stochastic and deterministic forces. This rigor directly informs drug discovery efforts aimed at modulating motor protein activity by identifying whether a candidate compound alters the diffusive search, the power stroke efficiency, or the coupling between them.

The operation of molecular machines—from kinesin walking on microtubules to the conformational cycling of ion channels—is fundamentally governed by stochastic processes. Thermal Brownian motion provides the necessary agitation, while asymmetric potentials, often fueled by chemical energy (e.g., ATP hydrolysis), bias this motion to perform work. The central challenge is to move beyond simply observing stochastic trajectories and instead construct predictive, quantitative models that describe the underlying energy landscapes and kinetic rules. This guide details the process of transforming time-series experimental traces into stochastic kinetic models, with the Fokker-Planck equation as a cornerstone formalism, directly situated within the research paradigm of understanding Brownian motion in biological nanomachines.

From Traces to Stochastic Models: A Methodological Pipeline

The workflow for building models from data follows a structured pipeline, integrating experimental biophysics, statistical analysis, and theoretical modeling.

Diagram Title: Workflow for Building Stochastic Models from Data

Experimental Protocols for Generating Traces

Key single-molecule techniques provide the essential time-series data.

Single-Molecule FRET (smFRET):

- Protocol: A biomolecular machine (e.g., ribosome, helicase) is labeled with donor (Cy3) and acceptor (Cy5) fluorophores. Under total internal reflection fluorescence (TIRF) microscopy, laser excitation (532 nm or 640 nm) induces FRET. The emitted fluorescence intensities (ID and IA) are recorded at 10-100 ms resolution using EMCCD or sCMOS cameras. The FRET efficiency E = IA / (ID + I_A) is calculated for each frame, producing a trace of conformational changes.

- Data Output: Time-series of FRET efficiency (0 to 1), reporting on intramolecular distances.

Optical Tweezers (Force Spectroscopy):

- Protocol: A molecular complex (e.g., RNA polymerase) is tethered between two micron-sized beads, one held in a pipette and the other in an optical trap. A near-infrared laser (1064 nm) creates the trap. The displacement of the bead from the trap center is measured via back-focal-plane interferometry, providing a force (pN) and extension (nm) trace. Force-clamp or position-clamp modes can be used.

- Data Output: Time-series of extension/position or force, reporting on mechanical steps and transitions.

Patch Clamp Electrophysiology:

- Protocol (Cell-Attached or Excised Patch): A glass micropipette (resistance 5-10 MΩ) forms a high-resistance seal (>1 GΩ) on a cell membrane containing an ion channel of interest. Voltage is clamped, and the ionic current through the channel(s) is amplified and digitized at high bandwidth (10-100 kHz).

- Data Output: Time-series of picoampere-scale currents, reporting on discrete channel opening and closing events.

Table 1: Representative Single-Molecule Studies Informing Kinetic Models

| Molecular System | Technique | Key Measured Parameters | Inferred Kinetic Rates | Reference (Example) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Kinesin-1 | Optical Tweezers | Step size: ~8.2 nm; Dwell time before step | Forward/Backward Stepping Rate at given ATP & load | [Svoboda et al., Nature 1993] |

| Ribosome | smFRET | FRET states during tRNA selection | Rate constants for tRNA binding, GTPase activation, proofreading | [Blanchard et al., Science 2004] |

| Voltage-Gated Na+ Channel | Patch Clamp | Open probability, mean open/closed times | Activation (αm), Inactivation (βh) rates as function of voltage | [Hodgkin & Huxley, 1952] |

| Rotary F1-ATPase | High-Speed Darkfield Imaging | Angular position vs. time; Pause durations | Stepping rate (120° steps) vs. ATP concentration; Binding/ hydrolysis constants | [Yasuda et al., Cell 1998] |

Core Analytical Steps for Model Building

Step 1 & 2: Pre-processing and Equilibrium Analysis

Data is filtered (e.g., Savitzky-Golay) and corrected for baseline drift. The equilibrium distribution of the observable (e.g., extension, FRET) is constructed.

- Hidden Markov Modeling (HMM): A critical tool for identifying discrete states within noisy traces and estimating transition probability matrices.

- Potential of Mean Force: From the equilibrium distribution Peq(x), a one-dimensional free energy profile is estimated: G(x) = -kB T ln(P_eq(x)), where x is the reaction coordinate.

Step 3 & 4: Dynamical Inference and Langevin Formulation

Dwell time analysis in discrete-state models yields rate constants. For continuous dynamics, a Langevin equation is posited:

m dx²/dt² = -γ dx/dt - dU(x)/dx + √(2γ k_B T) ξ(t)

where ξ(t) is Gaussian white noise. For molecular systems, the inertial term is negligible (overdamped limit), simplifying to:

γ dx/dt = -dU(x)/dx + √(2γ k_B T) ξ(t).

Here, U(x) is the potential energy landscape, and γ is the friction coefficient.

Step 5: Deriving the Fokker-Planck Equation

The overdamped Langevin equation translates to a Fokker-Planck (Smoluchowski) equation for the time-evolving probability density P(x,t):

∂P(x,t)/∂t = D * ∂/∂x [ (1/(k_B T)) * (dU(x)/dx) P(x,t) + ∂P(x,t)/∂x ]

where D = k_B T / γ is the diffusion coefficient. This equation describes the drift and diffusion of probability on the potential landscape U(x).

Diagram Title: Relationship Between Key Stochastic Equations

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table 2: Essential Materials and Reagents for Single-Molecule Kinetic Studies

| Item | Function/Description | Example Product/Type |

|---|---|---|

| Fluorophores for smFRET | Donor-Acceptor pair for distance sensing via Förster resonance energy transfer. | Cy3B (donor) & ATTO647N (acceptor); Janelia Fluor dyes (e.g., JF549, JF646). |

| Passivation Reagents | Reduce non-specific binding of biomolecules to surfaces/glass in microscopy. | Polyethylene glycol (PEG) silane; Pluronic F-127; BSA-biotin. |

| Enzymatic Oxygen Scavengers | Reduce photobleaching by removing dissolved oxygen. | Protocatechuate dioxygenase (PCD)/Protocatechuic acid (PCA) system; Glucose Oxidase/Catalase. |

| Triplet State Quenchers | Reduce fluorophore blinking by depopulating long-lived triplet states. | Cyclooctatetraene (COT), 4-Nitrobenzyl alcohol (NBA), Trolox. |

| Functionalized Beads | Surfaces for tethering molecules in force spectroscopy. | Streptavidin-coated polystyrene beads (for optical traps); Anti-digoxigenin-coated beads. |

| Nucleotide Analogs | To study kinetic cycles, often used as non-hydrolyzable or fluorescent analogs. | Adenosine 5′-[γ-thio]triphosphate (ATPγS); Mant-ATP; Cy3-ETP. |

| Zero-Mode Waveguides (ZMWs) | Nanostructures that confine light, enabling single-molecule observation at high μM ligand concentrations. | Commercial chips (e.g., PacBio SMRT cells). |

Model Validation and Application in Drug Development

A validated Fokker-Planck model allows simulation of dynamics under new conditions (e.g., different forces, ligand concentrations). In drug development, this framework is pivotal: