Bridging the Digital and Physical: A Modern Framework for Validating Molecular Simulations with Experimental Data

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating molecular simulations against experimental data. It covers foundational principles, from the critical trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost to the paradigm shift brought by machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) and massive quantum-chemical datasets. The piece details methodological applications across drug discovery and materials science, including spectral validation and solubility prediction. It further offers troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls and a framework for rigorous comparative analysis, synthesizing key takeaways to outline a future where integrated computational and experimental workflows accelerate biomedical innovation.

Bridging the Digital and Physical: A Modern Framework for Validating Molecular Simulations with Experimental Data

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and drug development professionals on validating molecular simulations against experimental data. It covers foundational principles, from the critical trade-offs between accuracy and computational cost to the paradigm shift brought by machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) and massive quantum-chemical datasets. The piece details methodological applications across drug discovery and materials science, including spectral validation and solubility prediction. It further offers troubleshooting strategies for common pitfalls and a framework for rigorous comparative analysis, synthesizing key takeaways to outline a future where integrated computational and experimental workflows accelerate biomedical innovation.

The Foundation of Trust: Core Principles and the New Era of Simulation Accuracy

Machine Learning Interatomic Potentials (MLIPs) represent a fundamental paradigm shift in molecular simulation, successfully bridging the long-standing gap between the high accuracy of quantum mechanical methods and the computational efficiency of classical force fields. For researchers in drug development and materials science, these neural network-based potentials enable large-scale, precise simulations of complex molecular systems that were previously computationally intractable, opening new frontiers in predictive modeling and rational design [1] [2] [3].

The Quantum Accuracy Gap: A Long-Standing Challenge

Traditional molecular simulation has long been caught between two extremes: high-accuracy quantum mechanical methods like Density Functional Theory (DFT) that are computationally prohibitive for large systems and long timescales, and classical force fields that offer efficiency but sacrifice accuracy and transferability [4] [3]. This "quantum accuracy gap" has limited our ability to model complex molecular phenomena with both precision and practical computational cost.

MLIPs resolve this dichotomy by learning the potential energy surface (PES) directly from quantum mechanical reference data, then reproducing this landscape with near-quantum accuracy at a fraction of the computational cost [1]. The MLIP functions as a PES that takes atomic configurations with positions and element types as input and maps them to a total energy, while also providing accurate forces and stresses as spatial derivatives of this energy surface [1].

Comparative Performance of Leading MLIP Architectures

Extensive benchmarking studies reveal how different MLIP architectures perform across diverse molecular systems, from organic crystals to inorganic materials. The table below summarizes quantitative performance data for leading MLIPs:

Table 1: Performance Benchmarks of Major MLIP Architectures

| MLIP Architecture | Force RMSE (meV/Å) | Energy RMSE (meV/atom) | Key Applications | Notable Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MACE [5] | 27-38 (naphthalene crystals) | 0.15-0.28 (naphthalene crystals) | Molecular crystals, vibrational dynamics | High body-order (up to 13), message-passing GNN |

| CAMP [3] | Comparable to state-of-the-art | Comparable to state-of-the-art | Periodic structures, 2D materials, organic molecules | Cartesian representation, no spherical harmonics |

| Universal MLIPs (M3GNet, MatterSim) [4] | Varies with pressure regime | Varies with pressure regime | Broad materials space across periodic table | Foundation models for diverse chemistry |

Table 2: Specialized Application Performance

| Application Domain | MLIP Model | Key Performance Metrics | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Polyacene Molecular Crystals [5] | MACE | Mean phonon frequency error: 0.17% (0.98 cm⁻¹); Excellent for C-H stretches | MD simulations stable for 1 ns; accurate vibrational spectra |

| High-Pressure Materials (0-150 GPa) [4] | Fine-tuned universal MLIPs | Accuracy degrades above standard pressure; recoverable via fine-tuning | Predicts pressure-induced structural changes |

| Polymer-Drug Interactions [6] | Classical MD (MLIP-enhanced) | Identified optimal polymer for 4.25 wt% drug loading | Confirmed enhanced cytotoxicity in MDA-MB-231 cells |

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Active Learning for Robust Training

Leading MLIP development employs sophisticated active learning strategies to ensure comprehensive coverage of the potential energy landscape [5]:

MLIP Active Learning Workflow

Validation Against Experimental Data

The true test of MLIP accuracy lies in validation against experimental observables. For drug delivery systems, researchers combine simulation with wet-lab validation:

- Computational Screening: MLIP or classical MD simulations predict polymer-drug interaction energies and binding affinities [6]

- Material Synthesis: Top-performing polymers identified computationally are synthesized (e.g., via ring-opening polymerization) [6]

- Experimental Characterization: Drug loading capacity, release kinetics, and cellular cytotoxicity are measured experimentally [6]

- Validation: Computational predictions are compared against experimental results, creating a closed feedback loop for model improvement [7]

Key Architectural Approaches in Modern MLIPs

Cartesian vs. Spherical Representations

The CAMP (Cartesian Atomic Moment Potential) architecture exemplifies recent innovations, using Cartesian moment tensors to represent atomic environments instead of traditional spherical harmonics [3]:

CAMP MLIP Architecture

Universal MLIP Foundations

Universal MLIPs (uMLIPs) represent another frontier, with foundation models trained on massive datasets encompassing broad regions of chemical space [1] [4]. These models include:

- M3GNet: Incorporates three-body interactions within graph neural networks [4]

- MACE-MPA-0: Uses density renormalization for improved high-pressure performance [4]

- DPA3: Trained on 163 million structures from diverse materials [4]

Table 3: Key MLIP Research Resources and Infrastructure

| Resource Type | Specific Tools/Databases | Primary Function | Access |

|---|---|---|---|

| Training Data | Alexandria database [4], Materials Project [4] | Source of quantum mechanical reference data | Public |

| MLIP Software | MACE [5], CAMP [3], ANI [1] | Training and deploying MLIP models | Open source |

| Validation Data | Molecular Dynamics Data Bank (MDDB) [8] | FAIR data principles for simulation data | Public (emerging) |

| Specialized MLIPs | Polyacene crystal potentials [5], High-pressure MLIPs [4] | Domain-specific pre-trained models | Research codes |

Current Limitations and Future Directions

Despite remarkable progress, MLIPs face several challenges that represent active research frontiers:

Long-Range Interactions: Standard MLIPs based on local atomic environments struggle with truly long-range forces like electrostatics [1] [5]

Data Scarcity in Extreme Regimes: Performance degrades in high-pressure environments (above 25 GPa) without targeted fine-tuning [4]

Complex Electronic Properties: Modeling magnetic systems, excited states, and electronic properties remains challenging [1]

Transferability: The balance between specialized accuracy and general applicability continues to evolve [1] [2]

The field is rapidly advancing toward more physically informed architectures, improved uncertainty quantification, and broader adoption of FAIR (Findable, Accessible, Interoperable, Reusable) data principles through initiatives like the Molecular Dynamics Data Bank [8].

MLIPs have fundamentally transformed the landscape of molecular simulation, effectively bridging the quantum accuracy gap that has long constrained computational science. For drug development professionals and materials researchers, these neural network potentials now enable the precise simulation of complex molecular systems—from drug-polymer interactions to molecular crystal dynamics—with unprecedented fidelity to quantum mechanical truth. As the field advances toward more robust universal models and standardized data practices, MLIPs are poised to become an indispensable tool in the computational scientist's arsenal, accelerating the discovery and design of novel materials and therapeutic agents.

The release of Meta's Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset represents a watershed moment in computational chemistry, offering an unprecedented resource for training machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs). This massive dataset of over one hundred million high-accuracy quantum chemical calculations enables the development of neural network potentials (NNPs) that can predict molecular energies with exceptional speed and accuracy [9]. However, the ultimate validation of any computational method lies in its ability to predict real-world experimental data. This guide provides an objective comparison of OMol25-trained models against traditional computational methods, with a specific focus on their performance in predicting experimental reduction potentials and electron affinities—critical properties in drug design and materials science [10] [11].

The OMol25 dataset addresses previous limitations in molecular datasets by combining unprecedented scale, diversity, and theoretical accuracy, establishing a new benchmark for molecular machine learning [9] [12].

- Scale and Scope: OMol25 comprises over 100 million quantum chemical calculations, totaling more than 6 billion CPU-hours of computational effort. This represents a 10-100x increase over previous state-of-the-art molecular datasets like SPICE and AIMNet2 [9].

- Theoretical Level: All calculations were performed at the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level of theory, a state-of-the-art range-separated meta-GGA functional that avoids many pathologies associated with earlier density functionals [9] [12].

- Chemical Diversity: The dataset provides exceptional coverage across biomolecules (from RCSB PDB and BioLiP2), electrolytes, and metal complexes, with additional inclusion of established community datasets to ensure comprehensive coverage [9].

- Electronic Structure Data: Beyond energies and geometries, the dataset includes advanced electronic structure information such as electronic densities, wavefunctions, and molecular orbital data from over 4 million calculations, enabling the development of physics-informed ML models [12].

Comparative Performance Analysis

Recent benchmarking studies have evaluated OMol25-trained NNPs against experimental data for charge-related molecular properties, providing critical insights into their real-world applicability compared to traditional computational methods [10].

Reduction Potential Prediction

Reduction potential quantizes the voltage at which a molecule gains an electron in solution, a property critical to understanding redox reactions in biological systems and energy storage. The following table compares the performance of OMol25-trained models with traditional density functional theory (DFT) and semiempirical quantum mechanical (SQM) methods on experimental reduction potential data for main-group and organometallic species [10].

Table 1: Performance Comparison for Reduction Potential Prediction (Values are Mean Absolute Error in V)

| Method | Main-Group (OROP) | Organometallic (OMROP) |

|---|---|---|

| B97-3c | 0.260 | 0.414 |

| GFN2-xTB | 0.303 | 0.733 |

| eSEN-S | 0.505 | 0.312 |

| UMA-S | 0.261 | 0.262 |

| UMA-M | 0.407 | 0.365 |

The data reveals a surprising trend: while B97-3c performs best for main-group species, the OMol25-trained UMA-S model demonstrates exceptional balanced performance across both chemical classes, with MAEs of 0.261V and 0.262V for main-group and organometallic species respectively [10]. This contrasts with traditional methods like GFN2-xTB, which shows significantly higher error for organometallic systems (0.733V) [10].

Electron Affinity Prediction

Electron affinity measures the energy change when a molecule gains an electron in the gas phase, fundamental to understanding molecular stability and reactivity. The following table summarizes method performance on experimental electron affinity data [10].

Table 2: Performance Comparison for Electron Affinity Prediction

| Method | MAE (eV) | Applicability Notes |

|---|---|---|

| r2SCAN-3c | 0.152 | Robust convergence |

| ωB97X-3c | 0.143 | Limited convergence for organometallics |

| g-xTB | 0.261 | No implicit solvent support |

| GFN2-xTB | 0.289 | Requires self-interaction correction |

| UMA-S | 0.138 | Broad applicability across elements |

For electron affinity prediction, the OMol25-trained UMA-S model achieves the highest accuracy (0.138 eV MAE) among all methods tested, demonstrating a significant advantage over both DFT and SQM approaches for this fundamental electronic property [10].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Benchmarking Workflow

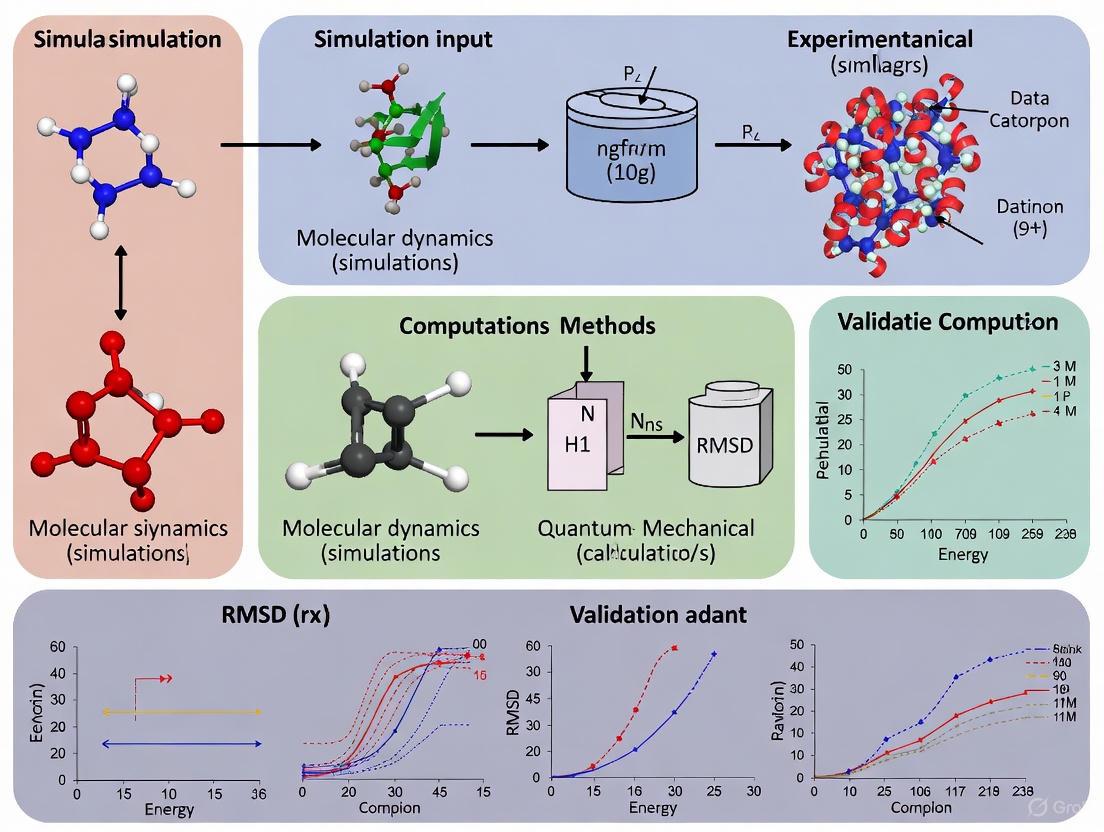

The evaluation of computational methods for predicting experimental molecular properties follows a standardized workflow to ensure fair comparison. The diagram below illustrates this benchmarking process.

Detailed Methodological Approach

The benchmarking methodology for reduction potential and electron affinity predictions involves several critical steps that ensure scientifically rigorous comparisons [10]:

Structure Preparation: Initial molecular structures for both reduced and non-reduced states are obtained from curated experimental datasets, with geometries pre-optimized using GFN2-xTB [10].

Geometry Optimization: All structures undergo rigorous geometry optimization using each computational method (NNPs, DFT, or SQM). For NNPs, optimizations are performed using the geomeTRIC package (version 1.0.2) to ensure consistent convergence criteria [10].

Energy Evaluation: Single-point energy calculations are performed on optimized geometries using the respective methods. For NNPs, this involves a forward pass through the trained network to predict the electronic energy [10].

Solvent Correction: For reduction potential calculations (which occur in solution), the Extended Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM-X) is applied to account for solvent effects on the electronic energy. Electron affinity calculations skip this step as they represent gas-phase phenomena [10].

Property Calculation: Reduction potential is calculated as the difference in electronic energy (converted to volts) between the reduced and non-reduced structures. Electron affinity is derived directly from the energy difference upon electron addition [10].

Statistical Analysis: Performance is quantified using mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square error (RMSE), and coefficient of determination (R²) against experimental reference data, with standard errors calculated to assess significance [10].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Successful implementation of molecular benchmarking studies requires specific computational tools and methodologies. The following table details key "research reagents" essential for this field.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents for Molecular Benchmarking

| Tool/Resource | Type | Primary Function | Application Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset | Training Data | Provides high-quality reference data for MLIP development | Foundation for training NNPs; enables transfer learning [9] [12] |

| OMol25-Trained NNPs | Computational Model | Fast, accurate energy and force prediction | UMA and eSEN architectures show best performance [10] [9] |

| geomeTRIC | Software Tool | Molecular geometry optimization | Ensures consistent convergence across methods [10] |

| CPCM-X | Solvation Model | Accounts for solvent effects in solution-phase calculations | Critical for reduction potential prediction [10] |

| ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD | DFT Method | High-accuracy reference calculations | Gold-standard theory level for training data [9] |

| OMol25 Leaderboard | Benchmarking Platform | Standardized model evaluation | Tracks progress across multiple MLIP architectures [13] |

Discussion and Implications

Performance Trends and Applications

The benchmarking data reveals several noteworthy trends with significant practical implications for research applications:

Complementary Strengths: OMol25-trained models, particularly UMA-S, demonstrate balanced performance across diverse chemical spaces, while traditional methods often excel in specific domains (e.g., B97-3c for main-group systems) but struggle with others (e.g., GFN2-xTB for organometallics) [10].

Charge and Spin Physics: Surprisingly, OMol25-trained models achieve competitive accuracy for charge-related properties like reduction potential and electron affinity despite not explicitly incorporating Coulombic interactions in their architectures. This suggests that the dataset's comprehensive coverage of charge and spin states enables effective implicit learning of these physical principles [10].

Computational Efficiency: NNPs trained on OMol25 provide "much better energies than the DFT level of theory I can afford" and enable "computations on huge systems that I previously never even attempted to compute," according to user feedback reported by Rowan scientists [9].

Limitations and Future Directions

Despite their impressive performance, OMol25-trained models have limitations that warrant consideration:

Architecture Dependence: Performance varies significantly across different NNP architectures, with UMA-S substantially outperforming eSEN-S and UMA-M on main-group reduction potential prediction [10].

Electronic Structure Limitations: The absence of explicit charge-based physics in current architectures may limit accuracy for properties dominated by long-range interactions, though this appears partially mitigated by comprehensive training data [10].

Active Development: The field is rapidly evolving, with new architectures like GemNet-OC showing promise for certain applications while struggling with optimization-based evaluations [13].

Future developments will likely focus on incorporating explicit physics, improving architecture efficiency, and expanding benchmarking to include additional molecular properties and chemical spaces.

The comprehensive benchmarking of OMol25-trained models against experimental data demonstrates their significant potential to accelerate molecular discovery across pharmaceutical and materials science applications. While traditional DFT and SQM methods remain valuable for specific applications, the balanced accuracy and computational efficiency of OMol25-trained NNPs, particularly the UMA-S model, make them compelling alternatives for researchers predicting molecular properties across diverse chemical spaces. As the OMol25 ecosystem continues to evolve through community engagement and leaderboard tracking, these models are poised to become indispensable tools in the computational chemist's toolkit, potentially representing an "AlphaFold moment" for molecular simulation [9].

In molecular simulation, robust validation is the cornerstone of methodological credibility. For decades, the root mean square deviation (RMSD) has served as a primary metric for assessing structural similarity. However, as computational models grow more sophisticated—evolving from classical force fields to machine-learned interatomic potentials (MLIPs)—the validation toolkit must expand accordingly. Relying solely on RMSD provides an incomplete picture, potentially overlooking critical inaccuracies in energetic landscapes, kinetic properties, and quantum mechanical behavior. This guide examines the comprehensive validation metrics essential for modern computational research, providing a structured comparison of methodologies and their performance in predicting reliable molecular properties for drug development and materials science.

The Evolution and Limits of RMSD

RMSD measures the average distance between atoms in superimposed structures, traditionally serving as a key metric for assessing structural convergence and similarity in biomolecular simulations.

Mathematical Foundation and Relationship to Experimental Data

The RMSD between two structures with coordinates X and Y is calculated as:

RMSD(X,Y) = √( (1/N) Σ_{i=1}^N ||x_i - y_i||^2 )

where N is the number of atoms, and x_i and y_i are the atomic positions. Under a set of conservative assumptions, an ensemble-average of pairwise RMSD,

Key Limitations of Isolated RMSD Use

- Insensitivity to Local Errors: A low global RMSD can mask significant local deviations in functionally critical regions, such as active sites.

- Lack of Energetic Information: RMSD is purely a geometric measure and provides no insight into the stability, strain, or relative energy of a conformation.

- Barrier to Kinetic Validation: It does not inform on the energy barriers governing reaction rates and conformational transitions, which are critical for understanding molecular function and drug binding [15].

Modern Validation Metrics: A Multi-Faceted Toolkit

Moving beyond RMSD requires a suite of validation metrics that collectively assess energy, dynamics, and electronic properties.

Energy and Force Prediction Accuracy

The accuracy of energies and atomic forces is a fundamental test for any potential energy model.

Core Concept: This measures how well a computational model reproduces the potential energy surface (PES) and the forces (negative gradients of the energy) compared to high-level quantum mechanical (QM) reference calculations. Accurate forces are particularly critical for stable and physically meaningful molecular dynamics simulations [9].

Experimental Protocol: Models are typically validated on benchmark datasets. For each molecular configuration in the test set, the model predicts the total energy and atomic forces. These predictions are compared against the reference QM values using metrics like Mean Absolute Error (MAE) for energies and forces.

Property-Based Benchmarks

Ultimately, a model's utility is determined by its ability to reproduce experimentally measurable properties.

Key Properties include:

- Binding Affinities: The strength of interaction between a protein and ligand.

- Thermodynamic Observables: Such as free energy differences, which can be derived from the potential of mean force.

- Kinetic Rates: Reaction rates and transition timescales, which depend on the energy barriers between states.

Experimental Protocol: For binding affinities, one common method is alchemical free energy perturbation (FEP) calculations, where the ligand is computationally "annihilated" from the binding site. The resulting free energy change is compared against experimental values from isothermal titration calorimetry (ITC) or surface plasmon resonance (SPR). Validating kinetics requires specialized datasets like Landscape17, which provide reference transition networks to test a model's ability to reproduce correct energy barriers and transition state geometries [15].

Potential Energy Surface and Kinetics Topology

This is a stringent test of a model's ability to capture the global organization of the energy landscape, not just local minima.

Core Concept: A model should correctly identify all stable minima and the transition states connecting them, without introducing spurious, unphysical stable points. This is vital for predicting reaction pathways and conformational dynamics [15].

Experimental Protocol: Using a benchmark dataset like Landscape17, the model is used to recalculate the kinetic transition network (KTN) of a molecule. The following are compared against the reference QM (DFT) data:

- The number and geometry of all minima and transition states.

- The connectivity of the network.

- The presence of any non-physical, stable structures predicted by the model.

Comparative Performance of Modern Modeling Approaches

The table below summarizes the performance of different modeling approaches across key validation metrics, illustrating the trade-offs between speed and accuracy.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of Molecular Modeling Approaches

| Modeling Approach | Energy/Force MAE | RMSD Performance | PES/Kinetics Topology | Computational Cost | Key Strengths |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Traditional Force Fields (e.g., GAFF, OPLS3e) [16] | High (vs QM) | Good for stable states | Poor; often incorrect barriers | Low | Speed, suitable for large systems and long timescales |

| Machine-Learned Potentials (e.g., eSEN, UMA) [9] | Very Low (vs QM) | Excellent | Good, but can produce spurious minima | Medium (High for training) | Near-QM accuracy for energies/forces on large systems |

| Quantum Mechanics (QM) | Reference | Reference | Reference (e.g., in Landscape17) | Very High | Highest accuracy, reference standard for electronic properties |

| Specialized MLIPs (Landscape17-tuned) [15] | Low | Excellent | Improved; fewer spurious states | Medium | Better reproduction of global kinetics and pathways |

The data shows that while modern MLIPs like Meta's eSEN and UMA models trained on the OMol25 dataset achieve "essentially perfect performance" on standard energy benchmarks [9], they still face challenges in kinetics. A study on the Landscape17 benchmark revealed that even state-of-the-art MLIPs missed over half of the DFT transition states and generated stable unphysical structures [15].

Table 2: Validation Metrics and Their Associated Experimental and Computational Benchmarks

| Validation Metric | Experimental Benchmark | Computational Benchmark Datasets | Interpretation Guide |

|---|---|---|---|

| RMSD / RMSF | X-ray B-factors [14] | PDB structures, MD trajectories | Lower is better; <1-2 Å often acceptable for backbone atoms. |

| Energy & Force MAE | N/A (vs QM reference) | OMol25 [9], rMD17 [15] | Force MAE < 1 kcal/mol/Å is often a target for high accuracy. |

| Binding Affinity | ITC, SPR data | MISATO [17], PDBbind | Error < 1 kcal/mol is considered excellent; context-dependent. |

| Kinetics & PES Topology | NMR, stopped-flow kinetics | Landscape17 [15] | Correct # of minima/transition states; no spurious states. |

A Practical Workflow for Comprehensive Model Validation

The following diagram illustrates a robust, multi-stage workflow for validating molecular models, integrating the metrics discussed above.

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

A well-equipped computational lab relies on a suite of software tools and datasets for model development, validation, and analysis.

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Tools for Validation

| Tool / Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Validation |

|---|---|---|

| MDAnalysis [18] | Analysis Library | A Python library for analyzing MD trajectories; calculates RMSD, RMSF, and other dynamics properties. |

| Landscape17 [15] | Benchmark Dataset | Provides kinetic transition networks for validating a model's reproduction of energy landscapes and kinetics. |

| OMol25 [9] | Training/Validation Dataset | A massive dataset of high-accuracy QM calculations for benchmarking energy and force accuracy on diverse molecules. |

| MISATO [17] | Integrated Dataset | Combines QM properties and MD traces of protein-ligand complexes for validating binding affinity predictions. |

| PDBbind | Database | A curated database of experimental protein-ligand binding affinities for validating free energy calculations. |

| VMD / OVITO | Visualization Software | Tools for visual inspection of structures and trajectories, complementary to quantitative metrics [19]. |

The field of molecular simulation has moved decisively beyond RMSD as a solitary validation metric. A rigorous assessment now requires a multi-pronged approach that interrogates a model's performance on energy and force accuracy, its prediction of experimental observables, and crucially, its faithful reproduction of the global energy landscape topology. While modern MLIPs have made remarkable strides in achieving near-quantum mechanical accuracy for energies, the Landscape17 benchmark reveals a critical frontier: the accurate prediction of molecular kinetics. Future progress will depend on the development of models and architectures that not only learn from static data but also intrinsically capture the physical principles governing molecular transitions, ultimately closing the loop between simulation and experiment.

From Theory to Practice: Methodological Workflows for Experimental Validation

Validating computational spectral data against experimental laboratory measurements is a cornerstone of modern analytical chemistry, particularly in pharmaceutical development and materials science. This process ensures that theoretical models, which are indispensable for predicting molecular behavior, accurately reflect reality. The core challenge lies in the multifaceted nature of spectra, which contain information on vibrational modes (IR, Raman), electronic transitions (UV-Vis), and molecular structure, all of which are sensitive to the chemical environment. As computational methods advance, robust validation protocols become critical for leveraging these tools in drug discovery and material characterization. This guide objectively compares the performance of different computational and experimental approaches, providing researchers with a framework for rigorous spectral validation.

Computational Methods for Spectrum Prediction

Density Functional Theory (DFT) Workflow

Density Functional Theory (DFT) is a widely used quantum mechanical method for predicting molecular spectra. A standard protocol involves:

- Molecular Geometry Optimization: The molecular structure is first optimized to its minimum energy conformation using a selected functional and basis set. For example, the B3LYP functional with the 6-311++G(d,p) basis set is a common choice for organic molecules [20].

- Frequency Calculation: On the optimized geometry, a frequency calculation is performed. This yields the IR intensities (dipole derivatives) and Raman activities (polarizability derivatives) for each vibrational normal mode.

- Spectrum Generation: The computed frequencies are typically scaled by an empirical factor (e.g., 0.9614) to correct for systematic overestimation and anharmonicity, then converted into a simulated spectrum [20].

- UV-Vis Prediction: Using Time-Dependent DFT (TD-DFT), the theoretical UV-Vis absorption spectrum is calculated from the optimized geometry, providing energies and oscillator strengths for electronic transitions [20].

Table 1: Standard DFT Protocol for Spectral Prediction

| Step | Key Parameter | Example(s) | Common Software |

|---|---|---|---|

| Geometry Optimization | Functional, Basis Set | B3LYP/6-311++G(d,p) [20] | Gaussian 09W, ORCA |

| Frequency Calculation | Scaling Factor | 0.9614 [20] | Gaussian 09W |

| UV-Vis Calculation | Method | TD-DFT [20] | Gaussian 09W |

Emerging Machine Learning (ML) and Neural Network Potentials (NNPs)

Machine learning, particularly deep learning, offers a faster alternative to traditional quantum chemistry calculations.

- Transformer Models for IR: Recent research uses encoder-decoder transformer architectures that take an IR spectrum and chemical formula as input to directly predict the molecular structure as a SMILES string. These models are pre-trained on hundreds of thousands of simulated spectra and fine-tuned on experimental data, achieving a top-1 accuracy of 44.4% for structure identification [21].

- Neural Network Potentials (NNPs): Models like Meta's eSEN and Universal Models for Atoms (UMA), trained on massive datasets such as Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25), can compute potential energy surfaces with accuracy rivaling high-level DFT (e.g., ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD) but at a fraction of the computational cost. This enables rapid spectral predictions for large systems like biomolecules and metal complexes [9].

Experimental Protocols for Laboratory Data Acquisition

Accurate and consistent experimental data is the essential benchmark for computational validation.

Fourier-Transform Infrared (FT-IR) Spectroscopy

The experimental FT-IR spectrum is acquired as follows [20]:

- Instrument: PerkinElmer spectrometer.

- Range: 4000 - 400 cm⁻¹.

- Settings: 100 scans per spectrum at a resolution of 2.0 cm⁻¹.

- Sample Preparation: The sample is analyzed in its solid state at room temperature.

FT-Raman Spectroscopy

The FT-Raman spectrum is collected under these conditions [20]:

- Instrument: BRUKER RFS 27 stand-alone FT-Raman spectrometer.

- Range: 4000 - 100 cm⁻¹.

- Settings: 100 scans per spectrum at a resolution of 2 cm⁻¹.

- Sample: Measured at room temperature.

UV-Visible Spectroscopy

The UV-Vis absorption spectrum is obtained using [20]:

- Instrument: Agilent Technology's Cary series UV-Vis spectrometer.

- Range: 900 - 200 nm.

- Sample Preparation: The compound is typically dissolved in a suitable solvent (e.g., water, methanol) at a concentration within the linear range of the Beer-Lambert law (e.g., 5–30 μg/mL for a compound like terbinafine hydrochloride) [22].

Critical Instrument Validation Steps

To ensure the reliability of experimental data, instrument performance must be validated regularly [23]:

- Wavelength Accuracy: Verified using standard materials with sharp emission (e.g., deuterium lamp peaks at 656.1 nm, 486.0 nm) or absorption peaks.

- Stray Light: Evaluated using a solution that blocks all light at a specific wavelength (e.g., sodium iodide at 220 nm). High stray light causes significant errors in high-absorbance samples [23].

- Photometric Accuracy: Checked with neutral density filters or standard solutions of known absorbance.

Case Study: Comparative Performance Analysis

A study on the chalcone derivative 4-[3-(3-methoxy-phenyl)-3-oxo-propenyl]-benzonitrile (4MPPB) provides a direct comparison between computational and experimental spectra [20].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of DFT vs. Experiment for 4MPPB

| Spectral Type | Key Experimental Peak(s) | Key Computational (DFT) Peak(s) | Agreement & Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| FT-IR | Multiple bands in 4000–400 cm⁻¹ range [20] | Scaled frequencies, PED analysis with VEDA 04 [20] | Good; scaled frequencies required for good correlation [20] |

| FT-Raman | Multiple bands in 4000–100 cm⁻¹ range [20] | Scaled frequencies, PED analysis with VEDA 04 [20] | Good; scaled frequencies required for good correlation [20] |

| UV-Vis | Absorption maximum at specific λ (data in [20]) | Predicted λ and oscillator strength via TD-DFT [20] | Good agreement on transition energy [20] |

| NMR (¹H & ¹³C) | Chemical shifts in DMSO-d₆ [20] | Chemical shifts calculated via GIAO method [20] | Good; used for structural verification [20] |

The following workflow summarizes the end-to-end process for generating and validating computational spectra against experimental data:

Diagram 1: Workflow for generating and validating computational spectra.

Advanced Techniques and Error Avoidance

Overcoming the "Fingerprint Region" Challenge with ML

A significant limitation of traditional IR analysis is the complex "fingerprint region" (400–1500 cm⁻¹), which is difficult to interpret manually. Transformer models can leverage the entire information content of an IR spectrum, not just a few functional group peaks, to predict molecular structure directly. This approach unlocks a much larger portion of the spectrum's potential for structure elucidation [21].

Parametrization-Free Methods for Complex Environments

In complex, heterogeneous solutions (e.g., ionic liquids, biomolecular mixtures), assigning spectral features to specific molecular interactions is challenging. The Instantaneous Frequencies of Molecules (IFM) method, coupled with molecular dynamics (MD) simulations, provides a parametrization-free way to predict vibrational frequency shifts and dynamics (like the Frequency-Fluctuation Correlation Function - FFCF) from atomistic simulations. This allows for the creation of molecular maps from vibrational observables in complex systems [24].

Common Pitfalls in Spectral Analysis and Validation

- Raman Calibration: Skipping wavelength and intensity calibration using a standard like 4-acetamidophenol leads to systematic drifts that can be mistaken for sample-related changes [25].

- Preprocessing Order: Performing spectral normalization before background correction (e.g., for fluorescence in Raman) introduces a strong bias, as the fluorescence intensity becomes encoded in the normalization constant [25].

- Model Overfitting: Using over-optimized preprocessing parameters or an overly complex machine learning model for a small dataset results in poor generalizability. Parameter selection should be based on spectral markers, not just model performance [25].

- Data Leakage in ML: During model evaluation, ensuring that all replicates from the same biological sample are in the same training/validation/test subset is paramount. Violating this independence inflates performance estimates dramatically [25].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents & Materials

Table 3: Key Reagents and Software for Spectral Validation Studies

| Item | Function / Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| DFT Software | Performs quantum chemical calculations for geometry optimization and spectral prediction. | Gaussian 09W [20], ORCA |

| Spectral Analysis Software | Assigns vibrational modes via Potential Energy Distribution (PED). | VEDA 04 [20] |

| Molecular Dynamics Software | Simulates molecular motion in solution for advanced methods like IFM. | GROMACS, LAMMPS |

| Wavelength Standard | Validates wavelength accuracy of spectrophotometers. | Deuterium lamp (656.1, 486.0 nm) [23], Holmium oxide filter |

| Stray Light Standard | Evaluates the level of stray light in a spectrophotometer. | Sodium Iodide (NaI) solution [23] |

| Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) | Provides highly accurate molecular energies and forces for large systems, fast. | Meta eSEN/UMA models [9] |

| Chemical Dataset | Trains and benchmarks machine learning models for chemistry. | Meta OMol25 [9] |

Intrinsically Disordered Proteins (IDPs) challenge the classical structure-function paradigm by existing as dynamic ensembles of interconverting conformations rather than stable three-dimensional structures. Their structural plasticity enables crucial roles in cellular signaling, regulation, and disease mechanisms, but also presents unique challenges for structural characterization. Traditional experimental techniques like X-ray crystallography are poorly suited for capturing this dynamic heterogeneity, while Molecular Dynamics (MD) simulations, though providing atomic-level detail, face prohibitive computational costs for adequate sampling. This comparison guide examines how artificial intelligence (AI)-enhanced methods are transforming our approach to IDP conformational sampling alongside refined traditional MD protocols, with a critical emphasis on validation against experimental data.

Understanding the Sampling Challenge for IDPs

The fundamental challenge in characterizing IDPs stems from their intrinsic flexibility and the vast conformational space they occupy. IDPs are typically enriched in polar and charged residues while being depleted in hydrophobic residues that form stable cores in folded proteins [26]. This composition results in heterogeneous structural ensembles where biologically relevant, transient states may be rare yet functionally critical [26].

Table 1: Key Characteristics of IDP Conformational Sampling

| Characteristic | Traditional Folded Proteins | Intrinsically Disordered Proteins |

|---|---|---|

| Native State | Single, stable tertiary structure | Ensemble of interconverting conformations |

| Energy Landscape | Funneled with deep energy minima | Flat with multiple shallow minima |

| Sampling Focus | Refining stable structure | Capturing diversity and transient states |

| Computational Demand | Moderate (nanoseconds-microseconds) | High (microseconds-milliseconds+) |

| Experimental Validation | High-resolution structure comparison | Agreement with ensemble-averaged data |

The limitations of conventional structural biology techniques have driven the adoption of computational methods. Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) spectroscopy and Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS) provide valuable ensemble-averaged data but cannot resolve atomic details of individual states [26] [27]. This validation gap makes the integration of computational and experimental approaches particularly critical for IDP research.

Traditional MD Approaches: Capabilities and Limitations

Molecular Dynamics simulations have long been the workhorse for studying IDP conformational landscapes at atomic resolution. Traditional MD applies physics-based force fields to simulate atomic motions over time, generating theoretical ensembles that can be validated against experimental observables.

Force Field Considerations and Specialized Protocols

The accuracy of MD simulations is heavily dependent on force field selection, with traditional protein force fields often producing overly compact IDP conformations [28]. Recent developments have yielded IDP-optimized force fields such as DES-Amber and a99SB-disp, which improve agreement with experimental data by adjusting dihedral angle parameters or water models [29] [27].

Enhanced sampling techniques like Gaussian accelerated MD (GaMD) have proven valuable for capturing rare events. In studying the ArkA IDP, GaMD simulations revealed proline isomerization events that led to a more compact ensemble with reduced polyproline II helix content, aligning better with circular dichroism data and suggesting a regulatory mechanism for SH3 domain binding [26].

Table 2: Performance Comparison of MD Force Fields for IDP Simulations

| Force Field | Water Model | Key Strengths | Documented Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| DES-Amber | TIP3P | Accurately captures helicity differences in COR15A wild-type vs mutant; best for dynamics per NMR relaxation [29] | Does not perfectly reproduce all experimental data [29] |

| a99SB-disp | a99SB-disp water | Reasonable initial agreement with NMR/SAXS data for multiple IDPs; good candidate for reweighting [27] | Performance varies across different IDP systems [27] |

| Charmm36m | TIP3P | Improved accuracy for folded proteins and IDPs [27] | May produce overly compact ensembles for some IDPs without reweighting [27] |

| ff99SBws | TIP3P | Captures helicity trends in COR15A | Overestimates helicity content [29] |

Maximum Entropy Reweighting: Integrating Simulation and Experiment

A significant advancement in traditional MD approaches is the development of maximum entropy reweighting procedures that integrate simulations with experimental data. This method minimally perturbs computational ensembles to match experimental restraints, effectively determining force field-independent conformational distributions [27].

The protocol involves:

- Running long-timescale MD simulations with different force fields

- Predicting experimental observables (NMR chemical shifts, SAXS profiles) for each simulation frame

- Reweighting the ensemble to maximize agreement with experimental data while minimizing deviation from the original distribution

- Validating the reweighted ensemble against withheld experimental data

In favorable cases where different force fields produce reasonable initial agreement with experiments, reweighted ensembles converge to highly similar conformational distributions, suggesting approximation of the true solution ensemble [27].

AI-Enhanced Approaches: Paradigm-Shifting Alternatives

Artificial intelligence, particularly deep learning, offers transformative alternatives by learning complex sequence-to-structure relationships from data rather than relying solely on physical laws.

Generative Autoencoders for Conformational Mining

Generative autoencoders represent a powerful AI framework for IDP conformational sampling. These systems reduce high-dimensional conformational spaces to lower-dimensional latent representations, then sample from these spaces to generate new conformations [30].

The workflow involves:

- Encoding: Representing IDP conformations as vectors in a reduced-dimensional latent space

- Distribution Modeling: Defining a multivariate Gaussian distribution from training data statistics

- Sampling: Drawing new vectors from the learned distribution

- Decoding: Reconstructing full atomic coordinates from sampled vectors

For proteins like Aβ40 and ChiZ, autoencoders trained on just 10-20% of MD simulation data can generate ensembles covering conformational diversity comparable to much longer simulations, with validation by SAXS profiles and NMR chemical shifts [30].

Transferable Ensemble Emulators and ML Potentials

Beyond protein-specific models, transferable AI ensemble emulators represent the cutting edge. These models, often built on architectures inspired by AlphaFold2, can sample conformational distributions across different protein sequences without system-specific retraining [31].

Coarse-grained machine learning potentials form another approach, using neural networks to parameterize simplified energy functions. Methods like variational force matching train coarse-grained forces to match all-atom forces, enabling faster exploration of conformational space while maintaining physical realism [31].

Comparative Analysis: AI vs. Traditional MD

Table 3: Direct Comparison Between Traditional MD and AI-Enhanced Sampling

| Parameter | Traditional MD | AI-Enhanced Sampling |

|---|---|---|

| Computational Cost | High (GPU-days to months) | Low to moderate (GPU-hours to days) |

| Sampling Efficiency | Low (correlated samples) | High (independent samples) |

| Physical Basis | Physics-first (force fields) | Data-first (learned distributions) |

| Rare Event Capture | Requires enhanced sampling | Built into generative process |

| Transferability | Force field dependent | System-specific training or limited transferability |

| Experimental Integration | Maximum entropy reweighting | Training data or conditioning |

| Interpretability | High (physical trajectories) | Lower (black box models) |

| Scalability to Large Systems | Limited by computational cost | Potentially higher with optimized architectures |

Performance Metrics and Validation

Quantitative validation against experimental data remains the gold standard for both approaches. Key metrics include:

- Radius of Gyration (Rg): Overall chain dimensions compared to SAXS data

- NMR Chemical Shifts: Agreement with residue-specific experimental measurements

- SAXS Profiles: Comparison of theoretical and experimental scattering patterns

- NMR Relaxation Parameters: Assessment of dynamic properties

For AI methods, reconstruction RMSDs between original and reconstructed test conformations provide internal validation, with reported values of 4.75-8.3 Å depending on protein size and training data [30].

Hybrid Approaches: The Best of Both Worlds

The most promising developments emerge from hybrid approaches that integrate AI and MD strengths. Physics-informed neural networks incorporate physical constraints into AI models, while methods like Boltzmann generators use neural networks to represent protein structures sampled from MD simulations as distributions in latent space [31].

Another hybrid strategy uses AI to accelerate MD sampling, then refines ensembles through maximum entropy reweighting with experimental data, creating a virtuous cycle of improvement [27].

Experimental Protocols and Validation Methodologies

Integrative Structural Biology Workflow

The following diagram illustrates a robust protocol for determining accurate IDP conformational ensembles by integrating computational and experimental approaches:

Key Experimental Techniques and Data Interpretation

Nuclear Magnetic Resonance (NMR) Spectroscopy

- Backbone Chemical Shifts: Sensitive indicators of secondary structure propensity

- Residual Dipolar Couplings: Provide orientational constraints in weakly aligning media

- Spin Relaxation Measurements: Probe dynamics on picosecond-nanosecond timescales

- Paramagnetic Relaxation Enhancement: Measures long-range distances in ensembles

Small-Angle X-Ray Scattering (SAXS)

- Guinier Analysis: Determines radius of gyration at low scattering angles

- Kratky Plot: Assesss chain flexibility and compaction

- Pair Distance Distribution Function: Reveals shape characteristics

- Computational Forward Models: Calculate theoretical profiles from atomic coordinates for direct comparison

Advanced scattering models like SWAXS-AMDE account for hydration layer density changes and thermal fluctuations of the solute, particularly important for IDPs [28].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions

Table 4: Key Research Reagents and Computational Tools for IDP Ensemble Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Tools/Reagents | Primary Function | Availability |

|---|---|---|---|

| MD Force Fields | DES-Amber, a99SB-disp, Charmm36m | Generate physics-based conformational ensembles | Academic licenses |

| AI Sampling Tools | Generative Autoencoders, Boltzmann Generators, DiG | Efficiently sample conformational diversity | Research code repositories |

| Experimental Data | NMR chemical shifts, SAXS profiles, CD spectra | Experimental validation of computational ensembles | Public databases (BMRB, SASBDB) |

| Analysis Software | SWAXS-AMDE, CRYSOL, WAXSiS | Calculate theoretical observables for validation | Open source / academic |

| Reweighting Algorithms | Maximum entropy reweighting protocols | Integrate computational and experimental data | Research publications [27] |

| Reference IDPs | Aβ40, α-synuclein, drkN SH3, ACTR | Benchmark systems for method development | Commercial peptide synthesis |

The comparison between AI-enhanced and traditional MD approaches for sampling IDP conformational ensembles reveals a rapidly evolving landscape where integration rather than competition provides the most promising path forward. Traditional MD with force field improvements and maximum entropy reweighting offers physically-grounded ensembles validated against extensive experimental data. AI methods deliver unprecedented sampling efficiency and can capture diverse states from limited training data. The convergence of reweighted ensembles from different force fields toward similar distributions when constrained by sufficient experimental data suggests that accurate, force field-independent IDP ensemble determination is achievable. This maturation points toward a future where integrated computational/experimental approaches will provide reliable atomic-resolution structural insights into disordered proteins, accelerating our understanding of their biological functions and therapeutic targeting.

Navigating Pitfalls: Strategies for Troubleshooting and Optimizing Simulation Protocols

Molecular dynamics (MD) simulations serve as powerful "virtual molecular microscopes," providing atomistic details into the dynamic behavior of biological systems that often complement and enhance experimental findings [32]. However, the predictive capability and scientific value of these simulations are fundamentally limited by the persistent challenge of discrepancies that arise when simulation results do not align with experimental data. These inconsistencies can stem from multiple sources within the complex framework of computational modeling, creating a significant diagnostic challenge for researchers. The process of validating molecular simulation requires careful consideration of numerous factors, including the accuracy of both the experimental data and the functions used to calculate observables from simulation, the sensitivity of these functions to molecular configuration, the relative timescales of simulation and experiment, and the degree to which the simulated system matches experimental conditions [33].

A critical insight from comparative studies reveals that even when different simulation packages reproduce various experimental observables equally well overall, subtle differences in underlying conformational distributions and sampling extent can lead to ambiguity about which results are correct [32]. This underscores the complexity of validation, as experiment cannot always provide the necessary detailed information to distinguish between underlying conformational ensembles. Furthermore, discrepancies tend to diverge more significantly when considering larger amplitude motions, such as thermal unfolding processes, with some packages failing to allow proteins to unfold at high temperature or providing results at odds with experiment [32]. This systematic guide examines the primary sources of simulation-experiment discrepancies, provides structured methodologies for their diagnosis, and offers evidence-based protocols for resolution, serving as a comprehensive resource for researchers engaged in the validation of molecular simulations.

Fundamental Limitations in Molecular Simulations

The accuracy of molecular simulations is constrained by two primary factors: the sampling problem and the accuracy problem [32]. The sampling problem refers to the challenge that lengthy simulations may be required to correctly describe certain dynamical properties, while the accuracy problem stems from insufficient mathematical descriptions of the physical and chemical forces that govern molecular dynamics. While much attention is often placed on force field limitations, it is crucial to recognize that protein dynamics are often more sensitive to the protocols used for integration of the equations of motion, treatment of nonbonded interactions, and various unphysical approximations [32].

Table 1: Primary Sources of Discrepancies Between Simulations and Experiments

| Source Category | Specific Factors | Impact on Results |

|---|---|---|

| Force Field Limitations | Empirical parameterizations, Classical approximations of quantum interactions, Functional forms [34] | Incorrect energy landscapes, Biased conformational preferences, Systematic errors in properties |

| Sampling Inadequacies | Short simulation timescales, Limited conformational space exploration, Slow dynamical processes [32] | Failure to observe rare events, Inaccurate equilibrium distributions, Unconverged statistical measures |

| Protocol Variations | Integration algorithms, Water models, Constraint methods, Nonbonded interaction treatment, Simulation ensemble [32] | Subtle differences in conformational distributions, Altered dynamics, Package-dependent behaviors |

| Observable Calculation | Imperfect forward models, Approximation in Q(rN) functions, Training biases in predictors [34] | Systematic errors in computed experimental observables, Misleading validation |

Experimental Limitations and Interpretation Challenges

Validation is further complicated by inherent characteristics of experimental data. Most experimental observables represent averages over both time and molecular ensembles, obscuring the underlying distributions and timescales that simulations can potentially reveal [32] [33]. Consequently, correspondence between simulation and experiment does not necessarily constitute a validation of the conformational ensemble produced by MD, as multiple diverse ensembles may produce averages consistent with experiment [32]. This is exemplified by simulations demonstrating how force fields can produce distinct pathways of the lid-opening mechanism of adenylate kinase that nevertheless sample the crystallographically identified conformers [32].

Additionally, the derivation of experimental observables often involves relationships that are functions of molecular conformation and are themselves associated with some degree of error. For instance, most chemical shift predictors produce chemical shifts from molecular structures via training against high-resolution structural databases, not solely via calculations from first principles [32]. This introduces another potential source of discrepancy that must be considered when comparing simulated and experimental results.

A Systematic Diagnostic Framework

Diagnostic Workflow for Discrepancy Investigation

The following diagram outlines a systematic approach for diagnosing sources of discrepancy between simulation results and experimental data:

This systematic workflow ensures that researchers comprehensively evaluate all potential sources of discrepancy rather than focusing prematurely on a single likely cause. The process begins with critical assessment of the experimental data itself, as inaccuracies in Qexp or mismatches between experimental and simulation conditions can lead to apparent discrepancies that do not reflect actual force field or sampling deficiencies [33]. Subsequent steps evaluate the principal computational factors, including force field limitations, sampling adequacy, protocol variations, and observable calculation methods.

Diagnostic Methodologies and Metrics

Table 2: Diagnostic Methods for Identifying Discrepancy Sources

| Diagnostic Method | Application | Interpretation Guidelines |

|---|---|---|

| Convergence Analysis | Assessing sampling adequacy for equilibrium and dynamic properties [32] | Multiple independent simulations; Statistical precision estimates; Timescale dependence evaluation |

| Multi-Force Field Comparison | Isolating force field-specific biases from other factors [32] | Consistent discrepancies across force fields indicate other issues; Package-specific patterns |

| Observable Sensitivity Testing | Determining how sensitive calculated observables are to conformational details [33] | High sensitivity requires more sampling; Low sensitivity suggests force field issues |

| Forward Model Validation | Testing the accuracy of Q(rN) functions for calculating observables [34] | Discrepancies may stem from forward model rather than structural ensemble |

Implementation of these diagnostic methodologies requires careful experimental design. For convergence analysis, Sawle and Ghosh demonstrate that the timescales required to satisfy stringent tests of convergence vary from system to system and are dependent on the assessment method used [32]. Similarly, multi-force field comparisons have revealed that while different MD packages reproduced experimental observables equally well overall at room temperature, there were subtle differences in underlying conformational distributions and sampling extent [32].

Resolution Strategies and Integration Methods

Computational Approaches for Consistency

When discrepancies are identified, several computational strategies can be employed to improve consistency between simulations and experimental data:

Reweighting Strategies: These approaches achieve consistency by reweighting trajectories obtained with a given force field after simulations have been completed. The three main principles are Maximum Entropy (MaxEnt), Maximum Parsimony (MaxPars), and Maximum Prior (MaxPrior), which adjust the weights of simulation snapshots to match experimental data while minimizing bias [34].

Experiment-Biased Simulations: Instead of reweighting after simulation, these methods add a bias to the force field during simulation to guide sampling toward regions consistent with experimental data. This includes methods like metadynamics, umbrella sampling, and other enhanced sampling techniques that incorporate experimental restraints [34].

Force Field Optimization: This approach uses experimental data to improve the physical description of macromolecules in a general and transferable way, rather than on a system-specific basis. Recent advances include using extensive quantum chemical calculations, such as those in the OMol25 dataset, to train neural network potentials that overcome traditional force field limitations [9].

Emerging Technologies and Future Directions

The field of molecular simulation is rapidly evolving with new technologies that address fundamental limitations. Neural network potentials (NNPs) trained on massive quantum chemical datasets like Meta's OMol25 represent a particularly promising development [9]. These models aim to provide fast and accurate computation of potential energy surfaces that avoid the shortcomings of both quantum mechanics and traditional force field approaches.

The OMol25 dataset addresses previous limitations in size, diversity, and accuracy, containing over 100 million quantum chemical calculations at the ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD level of theory, with particular focus on biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes [9]. Models trained on this dataset, such as eSEN and Universal Models for Atoms (UMA), demonstrate dramatically improved performance over previous state-of-the-art NNPs and match high-accuracy DFT performance on molecular energy benchmarks [9]. Such advances potentially circumvent many traditional sources of discrepancy by providing more accurate underlying energy surfaces.

Research Reagent Solutions: Essential Tools for Validation

Table 3: Key Research Reagents and Tools for Simulation Validation

| Tool Category | Specific Solutions | Function and Application |

|---|---|---|

| Simulation Software | AMBER, GROMACS, NAMD, ilmm [32] | Molecular dynamics engines with varying algorithms, performance characteristics, and compatibility |

| Force Fields | AMBER ff99SB-ILDN, CHARMM36, Levitt et al. [32] | Empirical potential energy functions with different parameterization strategies and target applications |

| Neural Network Potentials | eSEN models, UMA models [9] | Machine-learning potentials trained on large quantum chemical datasets for improved accuracy |

| Validation Datasets | OMol25, SPICE, ANI-2x, Transition-1x [9] | Curated collections of reference data for force field validation and development |

| Reweighting Tools | MaxEnt, MaxPars, MaxPrior implementations [34] | Software packages for rebalancing simulation ensembles to match experimental data |

| Enhanced Sampling | Metadynamics, Umbrella Sampling, Replica Exchange [34] | Algorithms to accelerate sampling of rare events and improve conformational exploration |

Each tool in this repertoire addresses specific aspects of the validation challenge. For example, the use of multiple simulation packages with the same force field can help isolate software-specific effects from force field limitations [32]. Similarly, neural network potentials like those trained on OMol25 can provide a more accurate reference for assessing traditional force fields, potentially revealing systematic errors that might otherwise be attributed to sampling limitations [9].

Diagnosing and resolving discrepancies between molecular simulations and experimental data requires a systematic approach that considers the multifaceted nature of both computational and experimental methods. By understanding the fundamental sources of discrepancy, implementing structured diagnostic workflows, employing appropriate resolution strategies, and leveraging emerging technologies, researchers can significantly enhance the predictive power and reliability of molecular simulations. The ongoing development of more accurate force fields, comprehensive validation datasets, and sophisticated integration methods promises to further strengthen the synergy between computational and experimental approaches in structural biology, ultimately leading to more profound insights into molecular mechanisms and more robust drug development pipelines.

Proof of Performance: Rigorous Validation and Comparative Analysis of Methods

In the field of computational chemistry, the arrival of next-generation Neural Network Potentials (NNPs) like the Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) and the equivariant Smooth Energy Network (eSEN) promises to reshape molecular simulation. A critical question remains: can these data-driven models, trained on massive quantum chemical datasets, truly rival the established accuracy of Density Functional Theory (DFT) and, most importantly, reproduce experimental observations? This guide examines benchmark studies that directly compare these models against DFT and experimental data, providing an objective analysis of their performance for research and development professionals.

Experimental Protocols and Benchmarked Systems

To ensure a fair and meaningful comparison, the benchmarking studies follow rigorous protocols, evaluating model performance across diverse chemical systems and key physicochemical properties.

Reduction Potential and Electron Affinity Benchmark

This benchmark assesses the ability of models to predict energies of molecules undergoing changes in charge and spin state, a challenging task for machine learning interatomic potentials (MLIPs) that do not explicitly encode the underlying Coulombic physics [10].

- Target Properties: Experimental reduction potential (in solvent) and electron affinity (in gas phase).

- Test Datasets:

- Computational Methodology:

- NNPs (eSEN-S, UMA-S, UMA-M): Geometry optimizations of both reduced and non-reduced species were performed using the NNPs. Single-point solvent corrections were applied using the Extended Conductor-like Polarizable Continuum Model (CPCM-X) for reduction potentials [10].

- DFT and SQM Methods: Low-cost DFT methods (B97-3c, r2SCAN-3c, ωB97X-3c) and semi-empirical quantum mechanical (SQM) methods (GFN2-xTB, g-xTB) were benchmarked against the same datasets for comparison. These calculations employed robust settings, including a (99,590) integration grid and density fitting to ensure convergence and accuracy [10].

General Molecular Energy and Force Benchmark

These benchmarks evaluate the core competency of NNPs: predicting energies and forces for a wide range of molecular structures.

- Target Properties: Molecular energies, interaction energies, and conformer energies.

- Test Datasets:

- Computational Methodology: The conservative-force versions of the models are typically used to ensure physical meaningfulness during geometry optimizations and molecular dynamics simulations [9] [35]. Predictions are made directly from the NNPs without further correction.

Molecular Crystal Structure Prediction (CSP)

This benchmark tests the application of universal MLIPs in a complex, real-world workflow where accurately capturing subtle intermolecular interactions is critical.

- Target Property: The ability to generate and correctly rank the stability of molecular crystal polymorphs.

- Computational Methodology (FastCSP Workflow):

- Structure Generation: Genarris 3.0 is used to generate thousands of random crystal packing arrangements for a given molecule [36].

- Geometry Relaxation and Ranking: The candidate structures are fully relaxed using the UMA model (with its OMC task). The relaxed structures are then ranked by their lattice energy calculated with UMA [36].

- Validation: The final ranked list is compared against known experimental crystal structures from the Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) to see if the experimental form is identified as the global minimum or lies within a narrow energy window (e.g., 5 kJ/mol) [36].

The following diagram illustrates the logical flow of a typical benchmarking study, from dataset selection to final performance evaluation:

Performance Data: A Quantitative Comparison

The table below summarizes key quantitative results from the benchmarking studies, providing a clear, data-driven view of model performance across different tasks and chemical domains.

Table 1: Performance of NNPs vs. DFT/SQM on Reduction Potential Prediction (Mean Absolute Error in V) [10]

| Method | Model Type | OROP (Main-Group) MAE (V) | OMROP (Organometallic) MAE (V) |

|---|---|---|---|

| B97-3c | DFT | 0.260 | 0.414 |

| GFN2-xTB | SQM | 0.303 | 0.733 |

| UMA-S | NNP | 0.261 | 0.262 |

| UMA-M | NNP | 0.407 | 0.365 |

| eSEN-S | NNP | 0.505 | 0.312 |

Table 2: Broader Benchmark Performance on Molecular Properties

| Benchmark / Property | Top Performing Models | Performance Notes |

|---|---|---|

| General Main-Group Chemistry (GMTKN55) | OrbMol-C, UMA, eSEN | All show high, roughly equivalent accuracy, often exceeding many DFT functionals [9] [35]. |

| Protein-Ligand Binding (PLA15) | OrbMol-C | Shows a tighter error distribution and fewer outliers compared to small UMA and eSEN models [35]. |

| Strained Conformers (Wiggle150) | OrbMol-C, eSEN, UMA | Achieve errors near chemical accuracy (1 kcal/mol), on par with high-level DFT [9] [35]. |

| Molecular Crystal Structure Prediction | UMA-S (in FastCSP) | Consistently identifies and correctly ranks experimental structures within 5 kJ/mol of the global minimum, eliminating the need for final DFT re-ranking [36]. |

| Molecular Dynamics Stability | OrbMol-C | Successfully simulated a solvated carbonic anhydrase enzyme (20,000+ atoms) with low RMSD and captured correct CO₂ binding [35]. |

This table lists essential computational tools, datasets, and models referenced in the benchmarking studies, which constitute the modern toolkit for AI-accelerated molecular simulation.

Table 3: Essential Resources for AI-Accelerated Molecular Simulation

| Resource | Type | Description & Function |

|---|---|---|

| OMol25 Dataset | Dataset | A massive dataset of >100M high-accuracy (ωB97M-V/def2-TZVPD) calculations used to train models like UMA and eSEN. Provides broad coverage of biomolecules, electrolytes, and metal complexes [9]. |

| UMA (Universal Model for Atoms) | Model | A universal NNP trained on multiple datasets (OMol25, OC20, OMat24). Uses a Mixture of Linear Experts (MoLE) architecture to handle different levels of theory and chemical domains [37] [9]. |

| eSEN (conservative) | Model | An equivariant NNP architecture emphasizing smooth potential energy surfaces. The conservative-force variant is recommended for stable geometry optimizations and dynamics [9]. |

| OrbMol (conservative) | Model | A fast and accurate NNP from Orbital Industries, built on the Orb-v3 architecture and trained on OMol25. Noted for its speed and strong benchmark performance [35]. |

| FastCSP Workflow | Software | An open-source workflow for Crystal Structure Prediction that uses UMA for all relaxation and ranking steps, bypassing the need for DFT [36]. |

| ASE (Atomic Simulation Environment) | Software | A Python library used to set up, run, and analyze atomistic simulations, commonly used as an interface for these NNPs [35]. |

The collective evidence from recent benchmarking studies indicates that next-generation NNPs like UMA, eSEN, and OrbMol are not just competitive with traditional low-cost DFT and SQM methods but are, in several key areas, superior. Their most significant advantage lies in their ability to inherit the high accuracy of their training data (often ωB97M-V) at a fraction of the computational cost, making high-level quantum chemistry feasible for large systems and high-throughput screening.

The benchmarks reveal a nuanced landscape:

- For main-group organic molecules, top NNPs are on par with DFT for energy prediction, and for organometallic complexes, they can significantly outperform low-cost DFT and SQM methods for charge-sensitive properties like redox potentials [10] [38].

- The speed and scalability of these models unlock previously intractable problems, such as full crystal structure prediction campaigns in hours or days and stable molecular dynamics of massive biomolecular systems [35] [36].

While challenges remain—such as limitations in describing extremely long-range interactions beyond their cutoff radius [39]—the trajectory is clear. Universal neural network potentials are rapidly validating their worth against experimental data, establishing themselves as indispensable tools in the computational scientist's arsenal for drug development, materials discovery, and molecular innovation.

The integration of molecular dynamics (MD) with machine learning (ML) is revolutionizing computational drug discovery. While ML models provide high-speed predictions of molecular properties, MD simulations offer profound insights into the structural dynamics and energetic landscapes of biomolecular interactions. This case study examines the emergent hybrid ML-MD paradigm, evaluating its performance against standalone methods for two critical tasks in pharmaceutical development: predicting drug-target interactions (DTI) and estimating compound solubility. The validation of these computational predictions against experimental data forms a core thesis in modern molecular simulation research, bridging the gap between in silico modeling and empirical observation [40].

Performance Benchmarking: ML-MD Models vs. Standalone Approaches

Drug-Target Interaction Prediction Accuracy

Table 1: Performance comparison of DTI prediction methods on BindingDB benchmark datasets.

| Method | Type | Dataset | Accuracy | ROC-AUC | Sensitivity | Specificity |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| GAN+RFC [41] | ML-only | BindingDB-Kd | 97.46% | 99.42% | 97.46% | 98.82% |

| GAN+RFC [41] | ML-only | BindingDB-Ki | 91.69% | 97.32% | 91.69% | 93.40% |

| BarlowDTI [41] | ML-only | BindingDB-kd | N/A | 93.64% | N/A | N/A |

| DeepLPI [41] | ML-only | BindingDB | N/A | 89.30% | 83.10% | N/A |

| MDCT-DTA [41] | Hybrid ML | BindingDB | MSE: 0.475 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| kNN-DTA [41] | ML-only | BindingDB-IC50 | RMSE: 0.684 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ada-kNN-DTA [41] | ML-only | BindingDB-IC50 | RMSE: 0.675 | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Molecular Docking [40] | Physics-based | Diverse targets | Variable | N/A | N/A | N/A |

Hybrid ML-MD models demonstrate complementary strengths, with ML components achieving high predictive accuracy for high-throughput screening, while MD simulations provide atomic-level interaction insights that enhance interpretability and reliability for specific target families. The GAN-RFC model showcases exceptional performance in binding affinity prediction for diverse datasets, while emerging hybrid architectures like MDCT-DTA balance prediction accuracy with structural insight [41].

Solubility Prediction Performance

Table 2: Performance comparison of solubility prediction methods for pharmaceutical compounds.

| Method | Type | Application | RMSE | R² | Key Metrics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost [42] | ML-only | scCO₂ solubility | 0.0605 | 0.9984 | 97.68% in AD |

| CatBoost-alvaDesc [42] | ML-only | scCO₂ solubility | 0.1200 | N/A | AARD: 1.8% |

| SVM-RBF [43] | ML-only | Lornoxicam/scCO₂ | N/A | High | Experimental correlation |

| ANN-PSO [42] | ML-only | scCO₂ solubility | N/A | N/A | Superior to EoS |

| LSSVM [42] | ML-only | scCO₂ solubility | N/A | 0.9975 | AARD: 5.61% |

| QSPR-ANN [42] | ML-only | scCO₂ solubility | 0.5162 | N/A | r: 0.9761 |

| Physics-informed NN [44] | Hybrid | Aqueous solubility | N/A | N/A | pH-dependent accuracy |

| ESOL [44] | Rule-based | Aqueous solubility | N/A | N/A | Linear regression |

For solubility prediction, ML models consistently outperform traditional thermodynamic approaches like equations of state and group contribution methods, particularly for complex drug-like molecules. The integration of physical principles, such as pH-dependent ionization in aqueous solubility or supercritical fluid behavior in scCO₂ processing, further enhances model accuracy and domain applicability [44] [42].

Experimental Protocols and Methodologies

Protocol for ML-Based DTI Prediction

The workflow for developing and validating ML models for DTI prediction involves several critical stages:

Data Curation and Feature Engineering: Established databases like BindingDB provide experimental binding affinities (Kd, Ki, IC50) for model training [41]. Molecular representations are extracted using:

- Drug Features: MACCS keys, PubChem fingerprints, ECFP, or graph representations from SMILES strings [41] [45]

- Target Features: Amino acid composition, dipeptide composition, or protein sequence embeddings from ProtBERT [46] [41]

Data Balancing: Addressing class imbalance through Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) to create synthetic minority class samples, significantly reducing false negatives [41].

Model Training and Validation: Implementing rigorous cross-validation with scaffold splitting to ensure generalization to novel chemical structures [45]. Performance evaluation using accuracy, precision, sensitivity, specificity, F1-score, and ROC-AUC [41].

Protocol for Hybrid ML-MD Validation

The hybrid methodology integrates computational efficiency with physical rigor: