Beyond Big Data: Advanced Strategies for Handling Sparse Data in Molecular Optimization

Molecular optimization in drug discovery and materials science often operates in data-sparse regimes where extensive experimental data is unavailable.

Beyond Big Data: Advanced Strategies for Handling Sparse Data in Molecular Optimization

Abstract

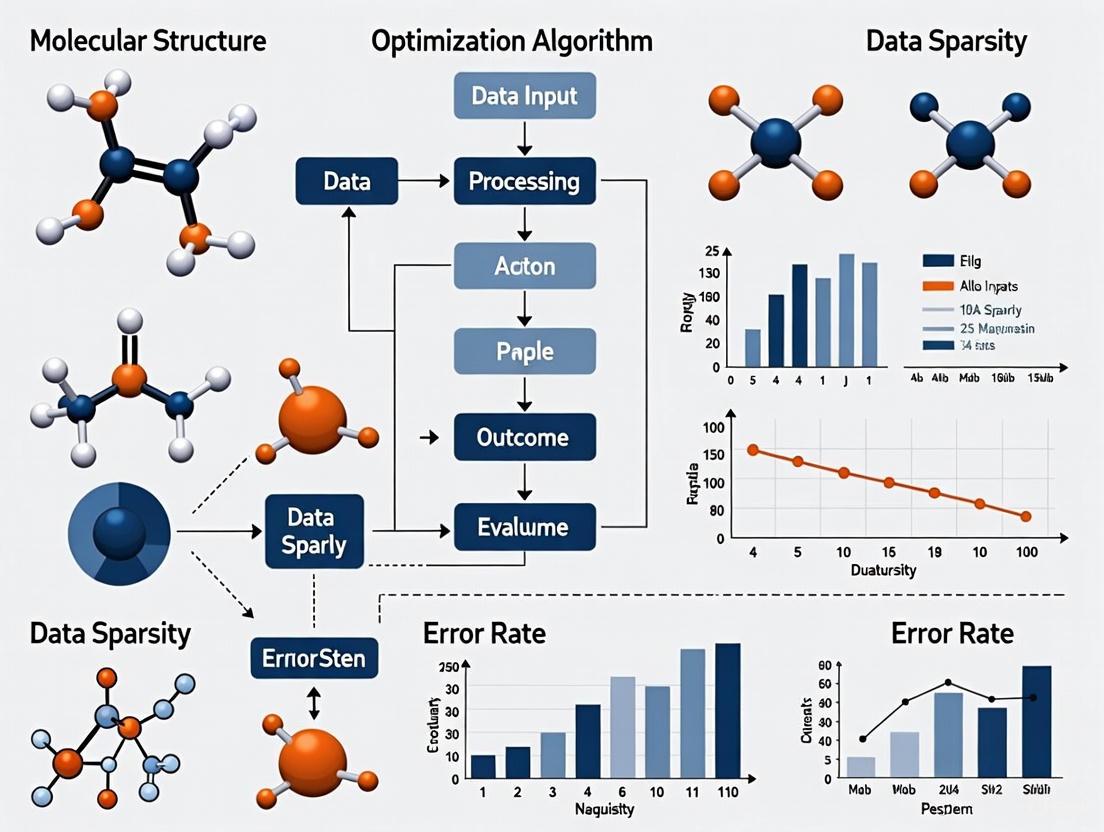

Molecular optimization in drug discovery and materials science often operates in data-sparse regimes where extensive experimental data is unavailable. This article provides a comprehensive guide for researchers and development professionals, exploring the fundamental challenges of sparse datasets and presenting cutting-edge methodological solutions. We detail practical applications of techniques like Bayesian optimization, sparse modeling, and specialized neural networks that excel with limited data. The content also covers essential troubleshooting for common implementation pitfalls and provides a rigorous framework for validating and comparing model performance. By synthesizing foundational knowledge with advanced, explainable AI strategies, this resource aims to equip scientists with tools to accelerate molecular optimization despite data limitations.

The Sparse Data Challenge: Understanding Molecular Optimization in Low-Data Regimes

FAQs: Understanding Sparse Data

What constitutes a "sparse" dataset in organic chemistry? From a data chemist's perspective, dataset sizes are often categorized as follows [1]:

- Small: Fewer than 50 experimental data points. These typically result from substrate or catalyst scope exploration.

- Medium: Up to 1000 data points, often generated through High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE).

- Large: More than 1000 data points, which can be from HTE or mined from literature.

Many experimental campaigns in both academia and industry generate datasets that are "sparse," meaning they are difficult to expand due to practical reasons like cost, resources, and experimental burden [1].

What are the common data structures encountered in sparse chemical data? The distribution of your reaction output is a key determinant for choosing a modeling algorithm. The four common structures are [1]:

- Reasonably Distributed: Ideal for regression tasks, providing a wider domain of applicability.

- Binned Data: Data grouped into categories (e.g., high vs. low yield), suitable for classification algorithms.

- Heavily Skewed: Data concentrated in one region, which may require acquisition of a better-distributed dataset before modeling.

- Singular Output: Datasets exhibiting essentially one output value, which also benefit from additional data collection campaigns.

How does data sparsity differ from the sparsity exploited in mechanism reduction? These are two distinct concepts:

- Data Sparsity: Refers to a limited number of experimental data points or missing values in a dataset [1] [2].

- Reaction Sparsity: A concept in combustion simulation where a chemical kinetic system is intrinsically governed by only a limited number of influential species or elementary reactions, allowing for the removal of surplus variables while maintaining prediction accuracy [3].

Troubleshooting Guides

Issue: Model Performance is Poor on Sparse Datasets

Problem: Statistical or machine learning models yield inaccurate predictions, lack chemical insight, or overfit when trained on sparse data.

Solution: Follow this systematic troubleshooting guide.

| # | Step | Action & Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Diagnose Data Structure | Create a histogram of your reaction output. Identify if your data is distributed, binned, skewed, or singular [1]. |

| 2 | Check Data Quality & Range | Ensure your dataset includes examples of both "good" and "bad" results. The range of outputs is critical for effective model performance [1]. |

| 3 | Re-evaluate Molecular Representation | Choose descriptors (e.g., QSAR, fingerprints, quantum mechanical calculations) appropriate for your dataset size and modeling goal. For sparse data, simpler descriptors can prevent overfitting [1]. |

| 4 | Select a Noise-Resilient Algorithm | For sparse, noisy data, consider algorithms like Bayesian optimization with trust regions (e.g., NOSTRA framework) or sparse learning techniques that are less susceptible to overfitting [4] [3]. |

Issue: Handling High-Dimensional Data with Missing Values

Problem: In genetic, financial, or health care studies, you have data with a large number of features (high-dimensionality) and missing values, making standard analysis difficult [2].

Solution: Implement modern machine learning techniques designed for this context.

| # | Step | Action & Description |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Choose an Imputation Method | Select a machine learning approach to estimate missing values [2]: • Penalized Regression: LASSO, Ridge Regression, SCAD. • Tree-Based Methods: Random Forests, XGBoost. • Deep Learning (DL): Neural network-based imputation. |

| 2 | Select an Estimator | Choose how to calculate your parameter of interest (e.g., population mean) [2]: • Imputation-based (II): Uses imputed values. • Inverse Probability Weighted (IPW): Uses response probabilities. • Doubly Robust (DR): Combines both models; remains consistent if either the imputation or response model is correct. |

| 3 | Validate and Compare | Both simulation studies and real applications show that DL and XGBoost often provide a better balance of bias and variance compared to other methods [2]. |

Experimental Protocol: Sparse Learning for Chemical Mechanism Reduction

This protocol details a data-driven sparse learning (SL) approach to reduce detailed chemical reaction mechanisms, exploiting the inherent sparsity of influential reactions in a kinetic system [3].

1. Objective Definition Define the goal of the reduction. Example: Create a reduced mechanism for n-heptane that accurately reproduces key combustion properties (e.g., ignition delay time) while minimizing the number of species and reactions [3].

2. Data Collection & Preprocessing

- Detailed Mechanism: Obtain a validated detailed mechanism (e.g., JetSurf 1.0 for n-heptane, containing 194 species and 1459 reactions) [3].

- Generate Training Data: Perform constant-volume adiabatic combustion simulations over a broad range of operating conditions (e.g., temperatures from 800 K to 1500 K, pressures from 1 atm to 50 atm, and equivalence ratios from 0.5 to 2.0). Record the state vector (species concentrations) and its time derivative at multiple time points [3].

3. Sparse Regression Setup

- Formulate the Problem: The goal is to find a sparse weight vector w that minimizes the difference between the true time derivative from the detailed mechanism and the time derivative calculated using only a subset of reactions [3].

- Apply Sparsity Constraint: Use a Lasso (L1) penalty term to enforce sparsity on the weight vector w, which pushes the weights of unimportant reactions to zero [3].

4. Model Training & Reaction Selection

- Optimize: Solve the sparse regression problem using modern optimization algorithms to find the optimal w [3].

- Identify Influential Reactions: Reactions with non-zero weights in the optimized w vector are retained in the skeletal mechanism [3].

5. Validation Validate the reduced mechanism by comparing its predictions against the detailed mechanism for key combustion properties not used in the training data, such as species concentration profiles and flame speeds [3].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential computational reagents for handling sparse chemical data.

| Research Reagent | Function & Application |

|---|---|

| Molecular Descriptors (e.g., QSAR, fingerprints) | Quantify molecular features mathematically to represent chemical structures for modeling. Critical for building predictive and interpretable models in low-data regimes [1]. |

| Sparse Learning (SL) Algorithm | A statistical learning approach that uses sparse regression (e.g., Lasso) to identify the most influential variables (reactions/species) in a high-dimensional system, enabling mechanism reduction [3]. |

| Bayesian Optimizer | A search algorithm, such as those used in multi-objective Bayesian optimization (MOBO), effective for reaction optimization when initial data is sparse or poorly distributed. It can help diversify reaction outputs [1] [4]. |

| Generative Multivariate Curve Resolution (gMCR) | A framework for decomposing mixed signals (e.g., from GC-MS) into base components and concentrations. Its sparse variant (SparseEB-gMCR) is designed for extremely sparse component matrices common in analytical chemistry [5]. |

| Multi-objective Genetic Algorithm (GA) | A heuristic optimization method that uses crossover and mutation on molecular representations (e.g., SELFIES, graphs) to explore chemical space and find molecules with enhanced properties, effective even with limited training data [6]. |

Molecular optimization is a critical stage in drug discovery, focused on modifying lead compounds to improve properties such as biological activity, selectivity, and pharmacokinetics while maintaining structural similarity to the original molecule [6]. Despite its importance, this field operates under significant data constraints that fundamentally limit research approaches and outcomes.

The inherent data-sparse nature of molecular optimization stems from the tremendous experimental burdens involved. Generating high-quality, reproducible biochemical data requires sophisticated instrumentation, specialized expertise, and substantial time investments [1]. The high costs associated with experimental characterization—including materials, labor, and equipment—naturally restrict the scale of datasets that research teams can produce. Consequently, researchers must often extract meaningful insights from what the field recognizes as "sparse" datasets, typically containing fewer than 50-100 experimental data points [1].

This technical support center provides troubleshooting guidance and methodologies for working effectively within these constraints, offering practical strategies for maximizing insights from limited experimental data in molecular optimization campaigns.

FAQ: Understanding Data Limitations in Molecular Optimization

Q1: What exactly constitutes a "sparse dataset" in molecular optimization? A: In molecular optimization, datasets are generally considered:

- Small: Fewer than 50 experimental data points

- Medium: 50-1000 data points

- Large: Over 1000 data points [1]

Most academic and industrial molecular optimization campaigns generate small to medium datasets due to experimental constraints. These sizes are particularly challenging given the vastness of chemical space, which contains billions of potential molecular structures to test [6].

Q2: Why is experimental data for molecular optimization so limited? A: Three primary factors constrain data generation:

- High experimental burden: Measuring properties like reaction rates, selectivity, or yield demands significant time and specialized expertise [1]

- Resource intensity: Costs for reagents, instrumentation, and personnel for high-throughput screening are substantial

- Characterization complexity: Determining molecular properties requires sophisticated techniques like protein-binding assays, solubility measurements, and ADMET profiling [7]

Q3: How do activity cliffs complicate molecular optimization with limited data? A: Activity cliffs occur when structurally similar molecules exhibit large differences in biological potency [8]. These present significant challenges because:

- They violate the fundamental similarity-property principle that underpins many predictive models

- Most machine learning models struggle to predict these dramatic potency changes [8]

- Limited data makes it difficult to identify and understand these edge cases during optimization

Q4: What are the most effective modeling approaches for sparse molecular datasets? A: With sparse datasets, simpler, more interpretable models often outperform complex deep learning approaches:

- Models based on molecular descriptors generally outperform more complex deep learning methods on sparse data [8]

- Statistical modeling strategies like linear regression, partial least squares, and random forests are less prone to overfitting [1]

- Reinforcement learning and genetic algorithms can effectively navigate chemical space with limited data [6] [9]

Troubleshooting Guides for Sparse Data Challenges

Challenge: Poor Model Performance with Limited Training Data

Symptoms:

- High error rates on validation compounds

- Inability to predict activity cliffs

- Model overfitting (low training error but high test error)

Solutions:

- Incorporate Transfer Learning

- Pre-train models on larger, related chemical datasets (e.g., ChEMBL)

- Fine-tune on your specific, smaller dataset

- This approach helps models learn general chemical principles before specializing [7]

Apply Data Augmentation Techniques

- Generate synthetic data points through molecular fingerprint manipulations

- Use domain-knowledge to create realistic hypothetical compounds

- Apply graph-based augmentation to molecular structures [9]

Utilize Multi-Task Learning

- Train models on multiple related properties simultaneously

- Share learned representations across tasks to improve generalization

- This is particularly effective when each property has limited data [7]

Table 1: Algorithm Performance Comparison on Sparse Data

| Algorithm Type | Data Efficiency | Interpretability | Activity Cliff Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Descriptor-Based ML | High | Medium | Moderate [8] |

| Deep Learning | Low | Low | Poor [8] |

| Genetic Algorithms | Medium | Medium | Variable [6] |

| Bayesian Optimization | High | Medium | Good [9] |

Symptoms:

- Inability to explore diverse chemical space

- Uncertainty about which experiments will provide maximum information

- Poor coverage of relevant molecular transformations

Solutions:

- Implement Strategic Dataset Design

- Prioritize molecular diversity over quantity

- Use clustering algorithms to identify representative compounds

- Focus on regions of chemical space with highest uncertainty [1]

Apply Active Learning Frameworks

Leverage Bayesian Optimization

- Build probabilistic models of the structure-activity landscape

- Use acquisition functions to balance exploration and exploitation

- Focus experimental resources on most promising regions [9]

Active Learning Workflow for Sparse Data

Experimental Protocols for Data-Efficient Molecular Optimization

Protocol: Building QSAR Models with Limited Data

Objective: Develop predictive Quantitative Structure-Activity Relationship (QSAR) models from small compound datasets (<50 molecules).

Materials:

- Chemical structures of tested compounds (SMILES or SDF format)

- Experimental activity data (IC50, Ki, EC50, or similar potency measures)

- Computational resources for molecular descriptor calculation

Methodology:

- Descriptor Calculation:

- Compute interpretable molecular descriptors (e.g., molecular weight, logP, polar surface area, hydrogen bond donors/acceptors)

- Avoid high-dimensional descriptors that may cause overfitting

- Select 5-10 most chemically relevant descriptors for your system [1]

Model Training:

- Use partial least squares (PLS) regression for datasets with <30 compounds

- Apply random forests or gradient boosting for datasets of 30-100 compounds

- Implement rigorous leave-one-out cross-validation to assess performance [1]

Model Validation:

- Calculate Q² (cross-validated R²) to evaluate predictive ability

- Apply domain of applicability analysis to identify reliable prediction regions

- Use y-randomization to confirm model significance [8]

Troubleshooting:

- If model shows poor predictive performance: Reduce descriptor dimensionality or incorporate additional chemical knowledge as constraints

- If model overfits: Increase regularization parameters or implement feature selection

Protocol: Genetic Algorithm Optimization with Experimental Validation

Objective: Optimize molecular properties through iterative design-make-test-analyze cycles with limited experimental capacity.

Materials:

- Initial lead compound with known structure and properties

- Synthetic chemistry resources for molecular synthesis

- Assay systems for property evaluation

Methodology:

- Initial Population Generation:

- Create initial population of 20-30 structural analogs through rational modifications

- Maintain structural similarity (Tanimoto similarity >0.4 to lead compound) [6]

Iterative Optimization Cycle:

- Synthesis: Prepare 5-10 highest-priority compounds per cycle

- Testing: Evaluate key properties (potency, selectivity, solubility)

- Analysis: Update fitness function based on experimental results

- Selection: Choose parent compounds for next generation based on multi-parameter optimization [6]

Termination Criteria:

- Stop when target property profile is achieved

- Or when consecutive cycles show minimal improvement (<10% gain)

Troubleshooting:

- If optimization stalls: Introduce greater structural diversity through crossover operations

- If synthetic access is limiting: Incorporate synthetic accessibility scores into fitness function [6]

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for Molecular Optimization

| Reagent/Category | Function in Optimization | Data Efficiency Consideration |

|---|---|---|

| CRISPR Screening Tools | Genome-wide functional studies to identify therapeutic targets [10] | Enables prioritization of most relevant targets before compound optimization |

| CETSA (Cellular Thermal Shift Assay) | Validates direct target engagement in intact cells [11] | Confirms mechanism with fewer compounds by measuring cellular target binding |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | Rapid parallel synthesis and testing of compound libraries [1] | Generates larger datasets but requires significant resources; best for focused libraries |

| Molecular Descriptor Software | Computes quantitative features for QSAR modeling [1] | Enables modeling without additional experiments; uses existing structural data |

Advanced Strategies for Sparse Data Scenarios

Leveraging Domain Knowledge and Constraints

Effective molecular optimization with limited data requires incorporating chemical knowledge as constraints:

Strategy 1: Structure-Based Constraints

- Apply medicinal chemistry rules (e.g., Lipinski's Rule of Five) to limit search space

- Incorporate known structure-activity relationship (SAR) trends as priors in models

- Use molecular scaffolding to maintain core structural elements [6]

Strategy 2: Multi-Objective Optimization

- Simultaneously optimize multiple properties (potency, selectivity, solubility)

- Use Pareto optimization to identify balanced solutions

- This approach makes efficient use of each data point by considering multiple endpoints [6] [9]

Constrained Multi-Objective Optimization

Data Representation Strategies for Enhanced Learning

The choice of molecular representation significantly impacts learning efficiency:

Descriptor Selection Guidelines:

- For datasets <50 compounds: Use interpretable, low-dimensional descriptors (e.g., physicochemical properties)

- For datasets 50-200 compounds: Employ extended connectivity fingerprints (ECFPs) or molecular graphs

- For datasets >200 compounds: Consider learned representations from autoencoders [1] [9]

Sparse Representation Techniques:

- Apply L1-norm regularization (Lasso) for automatic feature selection

- Use low-rank matrix completion to impute missing data points

- Implement compressed sensing principles to recover information from limited measurements [12]

Molecular optimization is inherently data-limited due to experimental constraints and high costs. However, strategic approaches can maximize insights from limited datasets. Key principles include:

- Embrace Model Simplicity: With sparse data, simpler, interpretable models often outperform complex deep learning approaches [8]

- Incorporate Domain Knowledge: Use chemical expertise to constrain optimization spaces and guide experimental priorities [1]

- Implement Strategic Experimentation: Apply active learning and Bayesian optimization to focus resources on most informative experiments [9]

- Leverage Transfer Learning: Utilize publicly available chemical data to pre-train models before fine-tuning on specific optimization tasks [7]

By adopting these data-efficient strategies, researchers can navigate the challenges of molecular optimization despite the inherent limitations of sparse datasets, ultimately accelerating the discovery of optimized therapeutic compounds.

FAQs: Understanding the Core Computational Challenges

Q1: What does it mean for a molecular optimization problem to be NP-hard? An NP-hard problem is at least as difficult as the hardest problems in the class NP (Nondeterministic Polynomial time). For molecular optimization, this means that as you increase the number of molecules or structural features in your search space, the computational time required to find the guaranteed optimal solution can grow exponentially. You cannot expect to find a perfect, scalable polynomial-time algorithm for such problems [13]. In practical terms, this applies to tasks like finding the global minimum energy conformation of a complex molecule or optimally selecting a molecular candidate from a vast chemical library, forcing researchers to rely on sophisticated heuristics and approximation algorithms [14] [13].

Q2: How can I tell if my optimization is stuck in a local optimum, and what can I do about it? A local optimum is a solution that is optimal within a small, local region of the search space but is not the best possible solution (the global optimum) [15]. Signs of being stuck include consistently arriving at the same suboptimal solution from different starting points or an inability to improve performance despite iterative tweaks. To escape local optima:

- Use Global Optimization Algorithms: Employ algorithms like Simulated Annealing or Genetic Algorithms, which are specifically designed to explore more of the search space and accept temporary "worse" solutions to escape local traps [15].

- Leverage Bayesian Optimization (BO): Frameworks like MolDAIS use probabilistic surrogate models to intelligently balance exploration (searching new regions) and exploitation (refining known good regions), making them highly effective for navigating complex molecular landscapes [16].

- Introduce Noise or Perturbations: Occasionally restarting the optimization from a new random point or adding noise to the process can help kick the search out of a local basin.

Q3: My model performs well on training data but poorly on new data. Is this the "curse of dimensionality"? This is a classic symptom. The curse of dimensionality refers to the phenomenon where, as the number of features (dimensions) in your data increases, the amount of data needed to train a robust model grows exponentially [17] [18]. In molecular contexts, you often have high-dimensional data (e.g., thousands of molecular descriptors, genetic features, or speech samples) but a relatively small number of samples [17]. This creates "blind spots"—large regions of the feature space without any training data. A model might seem to perform well on the sparse training points but will fail catastrophically when encountering new data from these blind spots after deployment [17]. This is a major reason for the failure of some AI models in healthcare, such as early versions of Watson for Oncology [17].

Q4: What strategies can mitigate the curse of dimensionality in molecular property prediction?

- Dimensionality Reduction and Feature Selection: Actively identify and use only the most relevant features. Techniques like the MolDAIS framework adaptively find a low-dimensional, task-relevant subspace within a large library of molecular descriptors, drastically improving data efficiency [16].

- Increase Sample Size: Whenever possible, gather more data. Multi-task learning, where a model is trained on several related prediction tasks simultaneously, can be an effective way to leverage additional data, even if it's sparse or weakly related [19].

- Use Simpler Models: In low-data, high-dimensional regimes, complex models like deep neural networks are prone to overfitting. Using simpler models or those with built-in regularization can improve generalizability.

- Data Augmentation: Artificially expand your training dataset by creating modified versions of your existing molecular data, if applicable to the property being studied [19].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Troubleshooting Poor Optimization Performance

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| The algorithm consistently converges to the same, suboptimal solution. | Trapped in a local optimum [15]. | Switch from a local search algorithm (e.g., Hill-Climbing) to a global optimizer (e.g., Simulated Annealing, Genetic Algorithm) [15] or a Bayesian Optimization framework [16]. |

| Optimization progress is extremely slow, even for small problems. | The problem may be NP-hard [13]; the search space is too large for an exhaustive search. | Focus on heuristic methods or approximation algorithms. Use a sample-efficient approach like Bayesian Optimization to guide experiments [16]. |

| Performance is highly variable and depends heavily on the initial starting point. | The objective function is multimodal (many local optima) [15]. | Perform multiple optimization runs with diverse initializations. Use algorithms designed for multimodal problems that maintain population diversity. |

Guide 2: Troubleshooting Poor Model Generalizability

| Observation | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|

| High accuracy on training data, low accuracy on test/validation data. | Overfitting due to the curse of dimensionality; the model has memorized the sparse training data [17]. | Reduce features via selection (e.g., MolDAIS [16]) or apply strong regularization. Increase training data size via collection or augmentation [19]. |

| Model performance degrades significantly when deployed on real-world data. | Dataset shift or blind spots in the training data; the real-world data occupies regions of feature space not covered during training [17]. | Audit training data for coverage and bias. Implement continuous learning to update the model with new, real-world data. |

| It is difficult to estimate how the model will perform before deployment. | Misestimation of out-of-sample error during development, a direct result of high dimensionality and small sample size [17]. | Use rigorous validation techniques (e.g., nested cross-validation). Be cautious of performance metrics from small, high-dimensional datasets. |

Experimental Protocols for Sparse Data

Protocol 1: Adaptive Subspace Optimization with MolDAIS

Objective: To efficiently optimize molecular properties in data-scarce, high-dimensional regimes. Background: The MolDAIS framework combats the curse of dimensionality by adaptively identifying a sparse, relevant subspace of molecular descriptors during the optimization loop [16]. Methodology:

- Featurization: Represent each molecule in your library using a comprehensive library of molecular descriptors (e.g., topological, electronic, geometric).

- Initialization: Select a small, random set of molecules and acquire their property values through experiment or simulation.

- Bayesian Optimization Loop:

- Surrogate Modeling: Train a Gaussian Process (GP) model on the acquired data. Crucially, use a sparsity-inducing prior (e.g., the SAAS prior) that allows the model to learn which descriptors are most relevant [16].

- Candidate Selection: Use an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement), which balances exploration and exploitation, to propose the next most promising molecule to evaluate.

- Evaluation & Update: Evaluate the proposed molecule (e.g., measure its property in the lab) and add the new data point to the training set.

- Iteration: Repeat step 3 until a satisfactory molecule is found or the experimental budget is exhausted. The identified relevant subspace becomes more refined with each iteration.

Protocol 2: Multi-Task Learning for Enhanced Generalization

Objective: To improve the accuracy and robustness of a molecular property prediction model for a primary task where data is sparse. Background: Multi-task learning (MTL) shares representations between related tasks, allowing a model to leverage information from auxiliary datasets, even if they are small or weakly related, which can mitigate overfitting and the curse of dimensionality [19]. Methodology:

- Task Selection: Identify a primary molecular property prediction task (with limited data) and one or more auxiliary tasks (e.g., other molecular properties) for which data is available.

- Model Architecture: Design a neural network with a shared encoder (that learns a general molecular representation) and multiple task-specific prediction heads.

- Training: Train the model jointly on all tasks. The loss function is typically a weighted sum of the losses for each individual task.

- Validation: Use a held-out test set for the primary task to evaluate the performance gain compared to a single-task model trained only on the primary data.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

| Item | Function in the Context of Sparse Data & Optimization |

|---|---|

| High-Fidelity DNA Polymerase (e.g., Q5) | Ensures sequence accuracy during PCR amplification, which is critical for generating reliable genetic data points and avoiding noise in high-dimensional biological datasets [20]. |

| Molecular Descriptor Libraries (e.g., RDKit) | Software libraries that generate standardized numerical features (descriptors) from molecular structures. These form the high-dimensional input for optimization and modeling tasks [16]. |

| Sparsity-Inducing Bayesian Optimization Framework (e.g., MolDAIS) | A computational tool that actively selects the most informative molecular features during optimization, making the search process data-efficient and combating the curse of dimensionality [16]. |

| Multi-Task Graph Neural Network (GNN) Models | A type of machine learning model that can learn from several molecular property prediction tasks at once, effectively increasing the sample size and improving generalization for data-scarce primary tasks [19]. |

| Hot-Start DNA Polymerase | Reduces nonspecific amplification in PCR, ensuring that the data generated (e.g., for genomic feature extraction) is specific and of high quality, which is paramount when working with limited samples [21]. |

Data sparsity presents a critical bottleneck in modern drug discovery, directly impacting development timelines, costs, and the likelihood of regulatory approval. In the context of molecular optimization research, sparse, non-space-filling, and scarce experimental datasets affected by noise and uncertainty can severely compromise the performance of AI/ML models that are inherently data-hungry. This technical support guide examines the tangible effects of data scarcity and provides actionable troubleshooting methodologies to enhance research outcomes in resource-constrained environments.

Quantitative Impact of Data Sparsity on Drug Discovery

Table 1: Documented Impacts of Data Scarcity on Discovery Metrics

| Impact Area | Documented Effect | Primary Evidence |

|---|---|---|

| Development Success Rate | Overall success rate from Phase I to approval as low as 6.2% [22] | Analysis of 21,143 compounds |

| Business Efficiency | Biotech funding down 50%; requirement to "squeeze more value" from limited funding [23] | Biotech industry index (XBI) performance |

| Model Performance | Limits AI/ML effectiveness; requires specialized approaches like multi-task learning [24] | Comprehensive review of AI in drug discovery |

| Operational Pressure | "No margin for error" in current biotech environment [23] | Industry expert commentary |

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide 1: Addressing Poor Model Performance with Sparse Data

Problem: Predictive models show poor generalization and high variance when trained on limited molecular property data.

Solution: Implement multi-task learning (MTL) frameworks.

Table 2: Multi-Task Learning Implementation Protocol

| Step | Action | Purpose | Key Parameters |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Identify Auxiliary Tasks | Select related but potentially sparse molecular property datasets [19] | Tasks sharing underlying biological features |

| 2 | Configure Architecture | Implement hard or soft parameter sharing [24] | Balance task-specific vs. shared layers |

| 3 | Train Jointly | Simultaneously learn all tasks [24] | Weighted loss function accounting for task importance |

| 4 | Validate | Use scaffold split or temporal split validation [19] | Assess generalization beyond chemical similarity |

Verification: MTL should outperform single-task baselines on your primary task, particularly when primary data is scarce (e.g., <1000 samples) [19].

Guide 2: Handling Experimental Noise in Sparse Datasets

Problem: Experimental uncertainty where identical inputs yield varying outputs compromises model accuracy.

Solution: Deploy noise-resilient frameworks like NOSTRA.

Experimental Protocol:

- Quantify Uncertainty: Characterize experimental noise levels in your data generation process [4].

- Incorporate Priors: Integrate prior knowledge of experimental uncertainty into surrogate models [4].

- Apply Trust Regions: Focus sampling on promising design space regions to maximize information gain [4].

- Iterate: Use active learning to selectively acquire new data points that reduce uncertainty most effectively [4] [24].

Expected Outcome: NOSTRA has demonstrated superior convergence to Pareto frontiers in noisy, sparse data environments compared to conventional methods [4].

Guide 3: Leveraging Limited Data for Mechanism of Action Prediction

Problem: Predicting Drug Mechanism of Action (MoA) with limited labeled examples.

Solution: Implement interpretable, sparse neural networks like SparseGO.

Methodology:

- Architecture Selection: Use sparse neural networks structured with biological hierarchies (e.g., Gene Ontology) [25].

- Input Processing: Utilize gene expression data (≈15,000 genes) rather than only mutations (≈3,000 genes) for richer input signals [25].

- XAI Integration: Apply explainable AI (XAI) techniques like DeepLIFT to identify critical neurons and biological pathways [25].

- Validation: Computationally validate MoA predictions using cross-validation on known drug sets (e.g., 265 drugs) [25].

Result: SparseGO significantly reduces GPU memory usage while improving prediction accuracy and MoA interpretability [25].

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the most effective strategies when I have less than 100 reliable data points for my target property?

Prioritize transfer learning and data augmentation. Transfer learning involves pre-training a model on a large, general molecular dataset (even if imperfectly related), then fine-tuning it on your small, specific dataset [24]. For data augmentation in molecular contexts, carefully apply techniques like matched molecular pair analysis or stereoisomer generation to artificially expand your training set while maintaining biochemical validity [24].

FAQ 2: How can I make my sparse data infrastructure more efficient?

Consolidate your data management. The extreme fragmentation across specialized platforms for different data types (genomics, imaging, tabular data) creates inefficiencies. Seek unified platforms that can handle multi-modal data—including tables, text files, multi-omics, metadata, and ML models—to simplify infrastructure and accelerate discovery timelines [26].

FAQ 3: Are synthetic control arms a viable option when patient recruitment is challenging?

Yes, this is an emerging and regulatory-accepted approach. Using real-world data (RWD) and causal machine learning (CML), you can create external control arms (ECAs). This can reduce the patient count needed for a trial by approximately 50% by eliminating or reducing placebo groups, directly addressing recruitment challenges and accelerating trial completion [23] [27].

FAQ 4: My dataset is small and noisy. Which methodology is most resilient?

Trust region-based multi-objective Bayesian optimization (exemplified by NOSTRA) is specifically designed for this scenario. It integrates prior knowledge of experimental uncertainty to construct more accurate surrogate models and strategically focuses sampling, making it highly effective for noisy, scarce datasets common in early discovery [4].

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 3: Essential Computational Tools for Sparse Data Research

| Tool / Resource | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| SparseGO | Sparse, interpretable neural network [25] | Drug response prediction & MoA elucidation |

| NOSTRA Framework | Noise-resilient Bayesian optimization [4] | Molecular optimization with uncertain data |

| Semi-Supervised Multi-task (SSM) Framework | Combines labeled and unpaired data [28] | Drug-target affinity (DTA) prediction |

| Federated Learning (FL) | Collaborative training without data sharing [24] | Multi-institutional studies with privacy concerns |

| Real-World Data (RWD) | Electronic health records, patient registries [27] | Clinical trial emulation & external controls |

Experimental Workflow Visualization

Sparse Data Solution Workflow

Multi-Task Learning Architecture

Multi-Task Learning Architecture

In molecular optimization research, the choice between sparse and big data AI is foundational, influencing everything from experimental design to the interpretability of results. Big Data AI relies on massive, complete datasets to train flexible models that identify complex patterns with minimal domain knowledge, often functioning as a "black box." In contrast, Sparse Data AI is specifically designed for limited data scenarios, incorporating expert knowledge and probabilistic methods to create transparent, explainable models grounded in known mechanisms [29].

The following FAQs and troubleshooting guides address the specific challenges you might encounter when applying these paradigms to molecular property prediction and drug design.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: My molecular property dataset has very few positive hits. Can AI still be effective?

Yes. Sparse data AI techniques are specifically designed for this scenario. Methods like multi-task learning (MTL) leverage correlations between related properties to improve prediction. Furthermore, Bayesian optimization provides a powerful framework for efficiently navigating the vast molecular search space with limited data, balancing the exploration of new candidates with the exploitation of promising ones [29] [30].

Q2: Why is my big data AI model performing poorly on our proprietary, smaller dataset?

This is a classic case of distributional shift and over-fitting. Large models trained on public, generic chemical datasets may not generalize to your specific, narrower chemical space. The model has likely learned patterns that are not relevant to your data. Switching to a sparse data approach that incorporates your specific domain knowledge as a prior can significantly improve performance [31] [29].

Q3: How can I trust an AI's molecular prediction when I can't see its reasoning?

This is a key differentiator between the paradigms. Big data AI often operates as a "black box." Sparse data AI, particularly methods using Bayesian optimization, is a "white box" approach. It provides a transparent, understandable mechanism for each prediction, which is crucial for building trust and achieving regulatory approval in pharmaceutical applications [29].

Q4: What is "negative transfer" in multi-task learning and how can I avoid it?

Negative transfer (NT) occurs when updates driven by one task degrade the performance on another task, often due to low task relatedness or severe data imbalance [32]. To mitigate it, use advanced training schemes like Adaptive Checkpointing with Specialization (ACS), which maintains a shared model backbone but checkpoints task-specific versions to protect against detrimental interference [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem: Over-fitting on Sparse Molecular Data

Symptoms: High accuracy on training data, but poor performance on new, unseen molecular structures or in experimental validation.

Solutions:

- Use Multi-Task Learning (MTL): Broaden the model's learning by training it on several related molecular properties simultaneously. This encourages the model to find more generalizable patterns [19] [32].

- Apply Dimensionality Reduction: Use techniques like Principal Component Analysis (PCA) or feature hashing to reduce the number of features and focus on the most informative signals, thereby removing noise [33].

- Employ Bayesian Methods: Implement Bayesian optimization which uses probabilistic surrogate models to handle uncertainty naturally, preventing overconfidence from sparse data [29].

- Adopt Sparse-Data Robust Algorithms: Choose algorithms known to be less affected by sparsity, such as certain tree-based methods, over others like logistic regression that can behave poorly [33].

Problem: Inefficient Search of Vast Molecular Space

Symptoms: The optimization process is slow, costly, and fails to find high-performing candidate molecules within a reasonable number of iterations or oracle calls.

Solutions:

- Implement an LLM-based Optimizer: Frameworks like ExLLM treat a large language model as the optimizer itself. They can leverage extensive chemical knowledge and reasoning capabilities to guide the search more intelligently than random or simple heuristic searches [30].

- Utilize Experience-Enhanced Learning: Use a system that maintains a compact, evolving memory of good and bad candidates (e.g., ExLLM's experience snippet). This prevents redundant exploration and improves convergence [30].

- Widen Exploration with k-Offspring Sampling: Generate multiple candidate molecules (

koffspring) per optimization step to better parallelize and explore the search space [30].

Problem: Handling Severe Data Imbalance and Missing Labels

Symptoms: Your dataset has a few properties with abundant data and others with very few labels, leading to biased models that ignore the low-data tasks.

Solutions:

- Apply Adaptive Checkpointing with Specialization (ACS): This MTL scheme monitors validation loss for each task individually and checkpoints the best model parameters for each task separately, shielding them from negative transfer [32].

- Use a Random Forest for Imputation: For missing feature values, use a Random Forest model to predict and impute missing data, as it can handle complex, non-linear relationships between variables [34].

Experimental Protocols & Data Presentation

Table 1: Quantitative Comparison of Sparse vs. Big Data AI in Molecular Research

| Aspect | Big Data AI | Sparse Data AI |

|---|---|---|

| Data Requirement | Massive, complete datasets (e.g., 10^6+ samples) [31] | Effective with limited data (e.g., <100 samples) [32] |

| Model Interpretability | "Black box" - limited explanation [29] | "White box" - transparent, causal inferences [29] |

| Core Methodology | Deep learning, flexible I/O models [29] | Bayesian optimization, multi-task learning [29] [32] |

| Handling Uncertainty | Poor, can be overconfident [31] | Native, via probabilistic modeling [29] |

| Best-Suited For | Broad exploration with abundant data [31] | Targeted optimization, expensive experiments [29] [32] |

Protocol 1: Implementing Multi-Task Learning with ACS for Imbalanced Data

This protocol is based on the ACS (Adaptive Checkpointing with Specialization) method detailed in Communications Chemistry [32].

1. Define Architecture:

- Backbone: A single Graph Neural Network (GNN) based on message passing to learn general-purpose molecular representations.

- Heads: Task-specific Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) attached to the backbone for each molecular property prediction task.

2. Training Procedure:

- Train the shared backbone and all task-specific heads simultaneously on your multi-task dataset.

- Monitor the validation loss for each individual task throughout the training process.

- Adaptive Checkpointing: For each task, save (checkpoint) the specific combination of backbone and head parameters every time that task achieves a new minimum in validation loss.

- Specialization: After training, for each task, select the checkpointed model that achieved its best validation performance.

Rationale: This approach allows for beneficial knowledge transfer between tasks through the shared backbone while preventing negative transfer by preserving task-specific optimal states [32].

Workflow Diagram: Sparse Data AI for Molecular Optimization

The diagram below illustrates a robust sparse data AI workflow for molecular optimization, integrating key concepts like Multi-Task Learning (MTL) and Bayesian optimization.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagents & Solutions

Table 2: Essential Computational Tools for Sparse Data AI

| Tool / Technique | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|

| Bayesian Optimization | Probabilistic model-based search for global optimum; balances exploration vs. exploitation [29]. | Efficiently navigating molecular search spaces with expensive-to-evaluate properties. |

| Multi-Task GNN | Graph Neural Network trained simultaneously on multiple property prediction tasks [32]. | Leveraging shared learnings across related molecular properties to combat data scarcity. |

| ExLLM Framework | Uses a Large Language Model as an optimizer with experience memory for large discrete spaces [30]. | Molecular design and optimization by leveraging chemical knowledge encoded in LLMs. |

| Principal Component Analysis (PCA) | Dimensionality reduction technique to convert sparse features to dense ones [33]. | Preprocessing sparse feature matrices (e.g., from one-hot encoding) to reduce noise and complexity. |

| Random Forest Imputation | ML-based method to predict and fill in missing values in a dataset [34]. | Handling missing data entries in experimental records before model training. |

| Adaptive Checkpointing (ACS) | Training scheme that checkpoints task-specific models to mitigate negative transfer [32]. | Training reliable MTL models on inherently imbalanced molecular datasets. |

Practical Solutions: Methodologies for Effective Sparse Data Molecular Optimization

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What is the primary advantage of using sparse models in Bayesian Optimization for molecular design? Sparse models make Bayesian Optimization computationally feasible and more sample-efficient when dealing with expensive-to-evaluate functions, such as molecular property assessments. By using a subset of data or a low-rank representation, they reduce the cubic computational complexity of full Gaussian Processes, allowing you to leverage larger offline datasets and focus representational power on the most promising regions of the chemical space [35] [36].

FAQ 2: My BO algorithm seems stuck in a local optimum. What might be going wrong? This is a common symptom of an incorrect balance between exploration and exploitation. It can be caused by several factors [35]:

- Over-smoothing from the surrogate model: Your sparse Gaussian Process might be spreading its limited representational capacity too thinly across the entire search space, failing to accurately model promising peaks [35] [36].

- Inadequate acquisition function maximization: If the inner optimization of your acquisition function (e.g., EI or UCB) is not thorough, it may miss the globally promising points [35].

- Excessively exploitative acquisition function: Functions like Probability of Improvement (PI) can be overly greedy. Switching to Expected Improvement (EI) or Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) can help by factoring in the magnitude of potential improvement or model uncertainty [37] [38].

FAQ 3: How do I know if my prior width is incorrectly specified? An incorrect prior width for your Gaussian Process can lead to poor model fit and, consequently, ineffective optimization. If the prior is too narrow, the model will be overconfident and may fail to explore. If it is too wide, the model will be overly conservative and slow to converge. Diagnosis often involves monitoring the model's likelihood on a validation set or observing a persistent failure to improve upon random search. The fix involves tuning hyperparameters like the kernel amplitude and lengthscale, often via maximum likelihood estimation [35].

FAQ 4: Can I use BO in the "ultra-low data regime" with fewer than 50 data points? Yes, but it requires careful setup. In this regime, the choice of prior and molecular descriptors becomes critically important. Furthermore, techniques like multi-task learning (MTL) can be employed to leverage correlations with related, data-rich properties. However, you must mitigate "negative transfer" where updates from one task harm another. Adaptive checkpointing with specialization (ACS) is a training scheme designed to address this issue, allowing a model to share knowledge across tasks while preserving task-specific performance [32].

Troubleshooting Guides

Problem 1: Poor Optimization Performance with Sparse Data

Symptoms: Slow convergence, failure to find global optimum, performance worse than random search.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Incorrect Prior Width [35] | Check the marginal log-likelihood of the GP on a held-out set. Examine if model uncertainty is consistently over/under-estimated. | Re-tune GP kernel hyperparameters (amplitude, lengthscale) via maximum likelihood or Bayesian optimization. |

| Over-smoothing by Sparse GP [35] [36] | Visually inspect the surrogate model's mean and variance. Check if it fails to capture local minima/maxima in known data regions. | Use a "focalized" GP that allocates more inducing points/resources to promising regions [36]. Consider a hierarchical approach that optimizes over progressively smaller spaces [36]. |

| Inadequate Acquisition Maximization [35] | Log the number of acquisition function restarts and the variance in proposed points. | Increase the number of multi-start points for the inner optimizer. Use a more powerful gradient-based optimizer if possible. |

Problem 2: Inability to Scale to High Dimensions or Large Offline Data

Symptoms: Long computation times per iteration, memory errors, model failure to fit.

| Potential Cause | Diagnostic Steps | Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Cubic Complexity of GP [36] [39] | Monitor wall time versus number of data points. A sharp increase indicates scalability issues. | Implement sparse Gaussian Processes (SVGP) [36] or use ensemble-based surrogates [36]. |

| Sparse GP is Overly Smooth [36] | The model fails to make precise predictions even in data-rich, promising regions. | Adopt the FocalBO approach: use a novel variational loss to strengthen local prediction and hierarchically optimize the acquisition function [36]. |

Experimental Protocols & Methodologies

Protocol 1: Basic Bayesian Optimization Loop for Molecular Design

This protocol outlines the standard workflow for using BO in a molecular optimization campaign [35] [37].

- Define the Input Space (

𝒳): Represent molecules using descriptors (e.g., molecular fingerprints, quantum chemical properties, graph-based features) [1]. - Initialize Dataset: Select a small set of initial molecules (e.g., via Latin Hypercube Design) and evaluate them through expensive experiments or simulations to obtain property values (

y). - Build Probabilistic Surrogate Model: Fit a Sparse Gaussian Process (SGP) to the collected data

D = (X, y). The SGP provides a posterior distribution over the unknown objective function. - Optimize Acquisition Function: Select the next molecule to test by finding the point

xthat maximizes an acquisition functionα(x)(e.g., Expected Improvement) based on the SGP posterior. - Evaluate and Update: Synthesize/test the proposed molecule

xto obtain its true property valuey, then add(x, y)to the datasetD. - Repeat: Iterate steps 3-5 until a stopping criterion is met (e.g., budget exhaustion, performance plateau).

The following diagram illustrates this iterative workflow:

Protocol 2: FocalBO for High-Dimensional Problems with Large Data

This advanced protocol is designed for scaling BO to high-dimensional problems (e.g., >100 dimensions) or when a large offline dataset is available [36].

- Offline Data Collection: Gather a large, pre-existing dataset

D_offlineof molecules and their properties. - Train Focalized Sparse GP: Train a sparse GP using a novel variational loss that focuses the model's representational power on regions of the space likely to contain the optimum, rather than fitting the entire function landscape equally well [36].

- Hierarchical Acquisition Optimization:

- Perform a coarse global optimization of the acquisition function (e.g., EI) to identify a promising sub-region.

- Define a trust region around this promising area.

- Perform a finer, local optimization of the acquisition function within this trust region to select the exact next point

x_t.

- Online Evaluation & Update: Evaluate the proposed molecule

x_tand add it to a combined dataset (D_offline + D_online). - Repeat: Iterate steps 2-4, updating the focalized GP with the growing dataset.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key computational tools and methodologies essential for implementing Bayesian optimization with sparse priors in molecular research.

| Item/Reagent | Function/Explanation | Application Context in Molecular Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| Sparse Gaussian Process (SGP) | A surrogate model that approximates a full GP using a subset of inducing points, reducing computational complexity from O(n³) to O(m²n) where m is the number of inducing points [36]. | Enables BO on larger datasets (offline or online) that would be prohibitive for standard GPs [35] [36]. |

| Focalized GP [36] | A specialized SGP trained with a loss function that weights data to achieve stronger local prediction in promising regions, preventing over-smoothing. | Used in high-dimensional problems to allocate limited model capacity to the most relevant parts of the molecular search space [36]. |

| Expected Improvement (EI) | An acquisition function that selects the next point based on the expected value of improvement over the current best observation, balancing probability and magnitude of gain [37] [38]. | The recommended default choice for most molecular optimization tasks, as it effectively balances exploration and exploitation [35] [38]. |

| Upper Confidence Bound (UCB) | An acquisition function that selects points with a high weighted sum of predicted mean and uncertainty (μ(x) + βσ(x)), explicitly encouraging exploration [37]. | Particularly useful in the early stages of optimizing a new reaction system to rapidly reduce global uncertainty [38]. |

| Low-Rank Representation [12] | A matrix representation technique that approximates a data matrix with a low-rank matrix, effectively capturing the most significant patterns while ignoring noise. | Can be used for cancer molecular subtyping and feature selection from high-dimensional genomic data by identifying clustered structures [12]. |

| Adaptive Checkpointing (ACS) [32] | A multi-task learning (MTL) scheme that checkpoints model parameters to mitigate "negative transfer," allowing knowledge sharing between tasks without performance loss. | Allows reliable molecular property prediction in ultra-low data regimes (e.g., <50 samples) by leveraging correlations with related properties [32]. |

Core Concepts & Definitions

Frequently Asked Questions

What distinguishes "white-box" sparse modeling from traditional "black-box" AI in molecular research? White-box sparse models are designed to be transparent and interpretable from the ground up. Unlike complex black-box models (e.g., dense neural networks), these models provide a clear, mechanistic understanding of how input features (like molecular descriptors) lead to a prediction. This is often achieved by intentionally limiting the model's complexity—for instance, by having each internal component respond to only a few inputs—which makes the internal decision-making process auditable and understandable [40].

Why is Bayesian Optimization (BO) particularly suited for sparse data problems? Bayesian Optimization provides a principled framework to solve the exploration vs. exploitation dilemma when data is limited. It uses probabilistic surrogate models to represent the unknown function (e.g., a molecular property). This model quantifies the uncertainty in its predictions, allowing the algorithm to strategically decide which experiment to perform next—either exploring areas of high uncertainty or exploiting areas predicted to be high-performing. This efficient learning strategy is closer to human-level learning, where only one or two examples are required for broader generalizations [29].

My model's explanations are focused on single atoms, but I think in terms of functional groups. How can I get more chemically meaningful attributions? This is a common limitation of some explanation methods. To gain insights into larger substructures, you can use contextual explanation methods. These techniques leverage convolutional neural networks trained on molecular images, where early layers detect atoms and bonds, and deeper layers recognize more complex chemical structures like rings and functional groups. By aggregating explanations from all layers, you can obtain a final attribution map that highlights both localized atoms and larger, chemically meaningful substructures [41].

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem: Optimization Process Gets "Stuck" in a Suboptimal Region of Molecular Space. This often occurs when using an unsupervised latent space for Bayesian Optimization. The mapping from the encoded space to the property value may not be well-modeled by a standard Gaussian process, causing the search to stagnate [42].

- Recommended Solution: Shift from an unsupervised latent representation to a defined feature space like molecular descriptors, and combine it with a Sparse Axis-Aligned Subspace (SAAS) Gaussian process model. The SAAS prior can rapidly identify the sparse subset of descriptors most relevant to the property being optimized, simplifying the inference task and requiring less data to make useful predictions [42].

Problem: Model Predictions are Inaccurate Due to High-Dimensional Features and Limited Samples. With thousands of possible molecular descriptors, the "curse of dimensionality" makes it difficult to build a reliable model with only a few dozen data points.

- Recommended Solution: Implement a feature selection step guided by sparsity. The SAAS Bayesian Optimization framework actively learns a sparse subspace of the most important features as data is collected. Alternatively, sparse regression methods like SISSO can be used to identify a small subset of critical descriptors, though they may assume a linear relationship with the target property [42].

Problem: Analytical Assay Error is Leading to Biased Parameter Estimates. Bioanalytical methods have inherent error, especially near the lower limit of quantification (LLOQ). Unaccounted for, this can distort the shape of the pharmacokinetic (PK) curve and lead to falsely overestimated parameters [43].

- Recommended Solution:

- Review bioanalytical validation reports before analysis to understand the assay's accuracy and precision profile [43].

- For population PK modeling, consider using the M3 method in software like NONMEM to properly handle data below the limit of quantification (BLQ), which avoids the bias introduced by simple methods like discarding or replacing BLQ values [43].

Experimental Protocols & Workflows

Detailed Methodology: The MolDAIS Framework for Molecular Property Optimization

The Molecular Descriptors and Actively Identified Subspaces (MolDAIS) framework is designed for efficient optimization in the low-data regime [42].

1. Molecular Representation:

- Input: Start with a set of candidate molecules.

- Feature Calculation: Use an open-source tool like Mordred to compute a comprehensive set of over 1800 molecular descriptors for each molecule. These are numerical quantities that encode chemical information from the molecule's symbolic representation [42].

- Data Normalization: Normalize all descriptor values to the range

[0, 1]to create a uniform search space [42].

2. Sparse Model Initialization & Sequential Learning:

- Surrogate Model: Use a Gaussian Process (GP) with a Sparse Axis-Aligned Subspace (SAAS) prior. This prior assumes that only a small subset of the many molecular descriptors is actually relevant to the target property [42].

- Acquisition Function: Employ an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) guided by the SAAS GP to select the most promising molecule for the next "expensive" evaluation (simulation or experiment) [42] [29].

- Iterative Loop: The process follows a key iterative sequence: the molecule selected by the acquisition function is evaluated, the resulting property data is used to update the SAAS GP model, and the model then adaptively refines its understanding of which sparse subspace of descriptors is most important. This loop repeats for a set number of iterations or until performance converges [42].

Workflow for Handling Problematic Pharmacokinetic (PK) Data

This protocol outlines steps to manage common data issues in PK analysis, such as missing samples or erroneous concentrations [43].

1. Data Quality Assessment & Exploration:

- Perform exploratory data analysis through summary statistics and plotting to identify missing data, questionable values, and concentrations below the limit of quantification (BLQ).

- Communicate with clinical and analytical teams to understand the root cause of data issues.

2. Selection of Handling Method:

- For BLQ Data: Use modern methods like the M3 method for population PK modeling, which incorporates the likelihood of the data being BLQ into the model estimation, providing less biased results compared to simple substitution [43].

- For Missing Covariate Data: Evaluate and apply suitable methods such as multiple imputation or model-based imputation, as complete case analysis can introduce bias.

3. Model Fitting & Diagnostic Evaluation:

- Fit the PK model using an appropriate estimation method (e.g., FOCE with interaction in NONMEM).

- Critically evaluate model performance by comparing parameter estimates, their relative standard errors (RSE), and measures of bias (e.g., relative mean error) and precision (e.g., root mean square error) against a control scenario with no missing data [43].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Computational Tools for Sparse, Interpretable AI in Molecular Research

| Tool / Solution Name | Primary Function | Key Application in Sparse Modeling |

|---|---|---|

| Mordred Descriptors [42] | Computes a large set (1,800+) of numerical molecular descriptors from a molecule's structure. | Provides a structured, high-dimensional feature space for optimization. Used as the input representation for the MolDAIS framework. |

| Sparse Axis-Aligned Subspace (SAAS) Prior [42] | A Gaussian Process prior that actively learns a sparse subset of relevant features during model training. | Drastically reduces the effective dimensionality of a problem, enabling efficient Bayesian Optimization with limited data. |

| Sparse Autoencoders [40] | Decomposes neural network activations into a set of discrete, interpretable features. | Used to analyze dense models post-training; helps isolate human-understandable concepts (e.g., functional groups) within a black-box model. |

| Contextual Explanation (Pixel Space) [41] | Provides model explanations by attributing importance in the space of a molecular image, aggregating across network layers. | Yields explanations that highlight both individual atoms and larger, chemically meaningful substructures, improving interpretability. |

| Control-Theoretic Analysis [44] | Treats a neural network as a dynamical system, using linearization and Gramians to analyze internal pathways. | Offers a principled, mechanistic way to quantify the importance of specific neurons and internal connections for a given prediction. |

Technical Support Center

Troubleshooting Guide

Q1: The optimization process is "stuck," making poor progress in finding improved molecules. What could be wrong?

- Potential Cause: The molecular representation (e.g., latent space from an unsupervised variational autoencoder) may not be well-structured for the property being optimized, or the surrogate model is struggling with high-dimensional data [42].

- Suggested Remedies:

- Switch to a descriptor-based representation: Use a comprehensive library of numerical molecular descriptors (e.g., from the Mordred software package) which often provides a more physically-grounded and structured search space [45] [42].

- Activate the SAAS prior: Ensure the Sparse Axis-Aligned Subspace (SAAS) prior is used with your Gaussian process model. This actively identifies and focuses on the most relevant molecular descriptors as data is acquired, mitigating the curse of dimensionality [46] [42].

- Verify data quality and diversity: Check that your initial dataset includes examples of both high- and low-performing molecules. A lack of "negative" data can severely limit the model's ability to learn [1].

Q2: My dataset is very small (fewer than 50 data points). Can I still use MolDAIS effectively?

- Potential Cause: Sparse data is a core challenge MolDAIS is designed to address. Ineffectiveness likely stems from an unsuitable algorithm choice or poorly distributed data [1].

- Suggested Remedies:

- Confirm data distribution: Plot a histogram of your property values. If the data is heavily skewed or "binned," consider using a classification algorithm to first distinguish high from low performers before proceeding with regression for optimization [1].

- Leverage interpretability: Use the MolDAIS model's interpretability to your advantage. After a few iterations, examine which molecular descriptors the model has identified as important. This can provide mechanistic insights and validate the model's direction before extensive data collection [46] [42].

- Incorporate domain knowledge: If possible, use the initial model to screen a large chemical library in silico. Select the top candidates and a few diverse molecules for the next round of testing to improve data diversity [1].

Q3: The computational cost of the optimization is too high. How can it be reduced?

- Potential Cause: Using all ~1800 molecular descriptors from a library like Mordred for every evaluation can be computationally expensive [42].

- Suggested Remedies:

- Use a screening variant: The MolDAIS framework introduces screening variants that significantly reduce computational cost. Implement one of these pre-screening methods to filter out less relevant descriptors early in the process [46].

- Start with a smaller subset: Begin the optimization with a strategically chosen, smaller subset of descriptors known to be relevant to your property class (e.g., polarizability for solubility, electronic parameters for redox potential) before scaling up to the full library.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: What types of reaction outputs or molecular properties can MolDAIS optimize? A: MolDAIS is flexible and can be applied to various properties, including yield, selectivity, solubility, stability, and catalytic turnover number [1]. It is effective for both single- and multi-objective optimization tasks [46].

Q: How does MolDAIS ensure interpretability, unlike a "black box" model? A: By using numerical molecular descriptors and the SAAS prior, MolDAIS actively learns a sparse subset of descriptors most critical for the target property. Researchers can directly inspect these selected descriptors (e.g., logP, polar surface area, HOMO/LUMO energies) to gain physical insights into structure-property relationships [45] [42].

Q: What is the typical scale of data efficiency demonstrated by MolDAIS? A: In benchmark and real-world studies, MolDAIS has been shown to identify near-optimal molecules from chemical libraries containing over 100,000 candidates using fewer than 100 expensive property evaluations (simulations or experiments) [46] [42].

Experimental Performance Benchmarks

The following table summarizes the key quantitative results from MolDAIS validation studies, demonstrating its data efficiency.

Table 1: MolDAIS Performance on Benchmark Tasks

| Optimization Task | Chemical Library Size | Performance Target | Evaluations to Target | Outperformed Methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| logP Optimization [42] | ~250,000 molecules | Find near-optimal candidate | ≤ 100 | Variational Autoencoder (VAE) + BO, Graph-based BO |

| Multi-objective MPO [46] | > 100,000 molecules | Balance multiple property goals | ≤ 100 | State-of-the-art MPO methods |

Detailed Experimental Protocol

This protocol outlines the core steps for implementing the MolDAIS framework for a molecular property optimization campaign.

Objective: To find a molecule with an optimal target property (e.g., redox potential for battery electrolytes) from a large chemical library using a minimal number of experimental measurements.

Workflow Overview:

Materials and Reagents:

- Chemical Library: A defined set of candidate molecules (e.g., >100,000 molecules) in a searchable digital format (SMILES strings, molecular graphs) [42].

- MolDAIS Software Framework: The implementation of the Bayesian optimization algorithm with the SAAS prior, as described in the original publications [46] [45].

- Descriptor Calculation Software: The Mordred software package is recommended for calculating a comprehensive set of over 1800 molecular descriptors directly from SMILES strings [42].

- Property Evaluation Method: The expensive "black-box" function, which could be an experimental assay (e.g., high-throughput electrochemical testing) or a computational simulation (e.g., Density Functional Theory calculation) [1] [42].

Step-by-Step Procedure:

- Descriptor Computation: For every molecule in the chemical library, compute the full vector of molecular descriptors using the Mordred calculator. Normalize all descriptor values to a common range (e.g., [0, 1]) [42].

- Initial Data Collection: Select a small initial set of molecules (e.g., 10-20) for property evaluation. This selection can be random or based on experimental design principles to ensure diversity. Record the property values to form the initial dataset ( D1 = {(xi, yi)}{i=1}^{N} ) [1].

- Model Fitting: Fit a Gaussian process (GP) surrogate model to the current dataset. The key is to use the Sparse Axis-Aligned Subspace (SAAS) prior on the GP lengthscales. This prior encourages the model to use only a small number of the most relevant descriptors [46] [42].

- Identify Sparse Subspace: From the fitted model, identify the molecular descriptors with significantly short lengthscales. These are the features the model has deemed most critical for predicting the target property.

- Candidate Selection: Using an acquisition function (e.g., Expected Improvement) defined over the sparse subspace, propose the next molecule or batch of molecules for evaluation. This function balances exploring uncertain regions and exploiting known high-performance areas.

- Property Evaluation & Update: Conduct the expensive property evaluation (experiment or simulation) for the proposed candidate(s). Add the new (molecule, property) pair to the dataset, updating it to ( D_{t+1} ).

- Iterate or Terminate: Repeat steps 3-6 until a stopping criterion is met. This is typically when a molecule meets a performance threshold or a predetermined budget of evaluations (e.g., 100) is exhausted.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 2: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools for MolDAIS

| Item Name | Function / Application in MolDAIS |

|---|---|

| Mordred Descriptor Calculator | Open-source software to compute a large library of >1800 molecular descriptors from SMILES strings, forming the foundational representation for the optimization [42]. |

| Sparse Axis-Aligned Subspace (SAAS) Prior | A Bayesian prior applied to the Gaussian Process model that actively identifies and sparsifies the descriptor space, focusing the model on task-relevant features [46] [42]. |

| Gaussian Process (GP) Surrogate Model | A probabilistic model that estimates the unknown property function and its uncertainty, which guides the selection of the next molecules to test [42]. |

| Acquisition Function (e.g., Expected Improvement) | A criterion that uses the GP's predictions to balance exploration and exploitation, deciding which molecule to evaluate next in the optimization loop [42]. |

| High-Throughput Experimentation (HTE) | A wet-lab methodology that enables the rapid experimental evaluation of the candidate molecules proposed by the MolDAIS algorithm, closing the design-make-test cycle [1]. |

ColdstartCPI is a computational framework designed to predict Compound-Protein Interactions (CPI) under challenging cold-start scenarios, where predictions are needed for novel compounds or proteins that were absent from the training data [47]. This is a critical capability in early-stage drug discovery, as traditional methods often fail with new molecular entities. The model innovatively moves beyond the rigid "key-lock" theory to embrace the more biologically realistic induced-fit theory, where both the compound and target protein are treated as flexible entities whose features adapt upon interaction [47] [48]. The framework integrates unsupervised pre-training features with a Transformer module to dynamically learn the characteristics of compounds and proteins, demonstrating superior generalization performance compared to state-of-the-art sequence-based and structure-based methods, particularly in data-sparse conditions [47].

Troubleshooting Guides & FAQs

This section addresses common challenges researchers may encounter when implementing or using the ColdstartCPI framework.

Data Preprocessing and Feature Extraction

Q: What should I do if the pre-trained feature extraction models (Mol2Vec or ProtTrans) produce feature matrices of incompatible dimensions for my compounds or proteins?

A: ColdstartCPI employs a dedicated Decouple Module to address this. If you encounter dimension mismatches:

- Verify Input Formatting: Ensure your compound SMILES strings and protein amino acid sequences are valid and correctly formatted.

- Utilize the MLP Projection Layers: The framework uses four separate Multi-Layer Perceptrons (MLPs) immediately after the pre-trained feature modules. These MLPs are designed to project the feature matrices of both compounds and proteins into a unified, compatible feature space [47] [48].

- Check Model Configuration: Confirm that the input dimensions of the first MLP layers align with the output dimensions of your pre-trained feature extractors.

Q: How can I improve model performance when my training dataset is extremely small and sparse?

A: The core design of ColdstartCPI specifically targets data sparsity. To enhance performance:

- Leverage Pre-trained Features: The use of Mol2Vec and ProtTrans provides rich, generalized representations learned from vast chemical and biological corpora, which mitigates the risk of overfitting to small datasets [47].

- Data Augmentation: Consider employing LLM-generated pseudo-data strategies, as demonstrated in related fields. For instance, the ChemBOMAS framework successfully used a fine-tuned LLM to generate informative pseudo-data from just 1% of labeled samples, robustly initializing the optimization process and alleviating data scarcity [49].

- Regularization: Ensure that dropout is enabled in the final fully connected prediction network, as this is a standard component of the ColdstartCPI architecture to prevent overfitting [47].

Model Training and Generalization

Q: The model performs well in warm-start settings but generalizes poorly to unseen compounds (compound cold start). What could be the issue?

A: Poor generalization in cold-start conditions often relates to inadequate learning of domain-invariant features.