Benchmarking AI Molecular Optimization: A 2025 Guide to Algorithms, Challenges, and Clinical Impact

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape of AI-driven molecular optimization for drug discovery.

Benchmarking AI Molecular Optimization: A 2025 Guide to Algorithms, Challenges, and Clinical Impact

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of the current landscape of AI-driven molecular optimization for drug discovery. It explores the foundational principles defining molecular optimization tasks and the critical role of benchmarks. The review systematically categorizes and evaluates leading algorithmic methodologies, from genetic algorithms and reinforcement learning to novel generative AI and collaborative LLM systems. It addresses persistent optimization challenges, including data sparsity and multi-objective balancing, and presents robust validation frameworks and comparative performance metrics. Finally, the article synthesizes key findings to project future directions, highlighting the transformative potential of these technologies in accelerating the development of safer, more effective therapeutics.

What is AI Molecular Optimization? Defining the Core Concepts and Critical Need

The drug discovery process is characterized by immense costs, extended timelines, and high failure rates that collectively form a significant bottleneck in delivering new therapies to patients. On average, conventional drug development takes approximately 12 years and costs around USD 2.6 billion from discovery to market approval [1]. This expensive and time-consuming process faces its greatest challenges during the clinical trial phase, where a single trial can cost anywhere from USD 1 million to USD 100 million, with patient recruitment delays representing the single largest cause of cost overruns [2]. The inherent complexity of human pathophysiology, coupled with the vastness of chemical space, necessitates rigorous decision-making at each stage of the discovery process, with strategic optimization of lead molecules significantly increasing their likelihood of success in subsequent preclinical and clinical evaluations [1].

Artificial intelligence (AI), particularly machine learning and deep learning approaches, has emerged as a transformative force in addressing these challenges. AI-driven molecular optimization has revolutionized lead optimization workflows, significantly accelerating the development of drug candidates [1]. These technologies promise to streamline the transition from initial discovery to clinical validation by improving the quality of lead molecules earlier in the pipeline. This review benchmarks current AI molecular optimization approaches against traditional methods, providing researchers with experimental protocols and performance comparisons to guide methodology selection in their drug discovery efforts.

Established Practices: Traditional Screening & Optimization

High-Throughput Screening (HTS) Limitations

For decades, pharmaceutical companies have relied on high-throughput screening (HTS) as the first step in the drug discovery process [3]. This approach involves physically testing thousands to millions of compounds against biological targets to identify initial hits. A fundamental limitation of HTS is the necessity to synthesize all compounds used in the screen before testing can begin [3]. This physical constraint significantly limits the number of compounds that can be evaluated, restricting the explorable chemical space and hindering the discovery of novel drug candidates.

The hit rate in a typical HTS is notoriously low, typically less than 1% in most assays, requiring enormous compound libraries to generate sufficient hits for drug development programs to progress [4]. With costs for modern screening campaigns often running into the hundreds of thousands of dollars and per-well costs frequently exceeding $1.50, the economic burden of comprehensive HTS has become substantial [4]. As drug discovery has shifted toward more disease-relevant but complex phenotypic readouts, these costs have increased further, creating an urgent need for more efficient screening methodologies.

The Molecular Optimization Challenge

Molecular optimization represents a critical stage in drug discovery following the identification of lead molecules. This process focuses on the structural refinement of promising leads to enhance their properties while maintaining core structural features that confer desired activity [1]. The formal definition involves: given a lead molecule x with properties p₁(x), ..., pₘ(x), generate a molecule y with properties p₁(y), ..., pₘ(y), satisfying pᵢ(y) ≻ pᵢ(x) for i = 1,2,...,m and sim(x,y) > δ, where sim(x,y) represents structural similarity and δ is a similarity threshold [1].

This optimization must navigate an intractably large chemical space. For example, with 20 available building blocks, researchers can produce nearly as many 60-unit sequences as the number of atoms in the known universe (roughly 10⁸⁰) [5]. As sequence length and building block diversity increase, the number of possible variants grows combinatorially, creating a search challenge that exceeds the capabilities of traditional empirical approaches.

AI-Driven Approaches: Methodologies and Workflows

AI-aided molecular optimization methods typically involve two fundamental steps: (1) construction of a chemical space representation, and (2) implementation of an optimization approach to identify desired molecules within this space [1]. These methods can be broadly categorized based on their operational spaces: discrete chemical spaces and continuous latent spaces, each with distinct optimization strategies.

Molecular Optimization in Discrete Chemical Spaces

Methods operating in discrete chemical spaces employ direct structural modifications based on discrete molecular representations such as SMILES (Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System), SELFIES (SELF-referencing Embedded Strings), and molecular graphs where nodes represent atoms and edges represent chemical bonds [1]. These approaches typically explore chemical space through iterative processes of structural modification and selection, primarily using genetic algorithms or reinforcement learning.

Genetic Algorithm (GA)-Based Methods use heuristic optimization inspired by natural selection, beginning with an initial population and generating new molecules through crossover and mutation operations [1]. Molecules with high fitness are selected to guide the evolutionary process. Approaches like STONED generate offspring by applying random mutations to SELFIES strings, while MolFinder integrates both crossover and mutation in SMILES-based chemical space [1]. For multi-objective optimization, GB-GA-P employs Pareto-based genetic algorithms on molecular graphs to identify sets of Pareto-optimal molecules with enhanced properties [1].

Reinforcement Learning (RL)-Based Methods such as GCPN (Graph Convolutional Policy Network) and MolDQN utilize reward signals to guide the generation of molecules with desired properties [1]. These approaches frame molecular optimization as a sequential decision-making process where an agent learns to take actions (molecular modifications) that maximize cumulative rewards (improved properties).

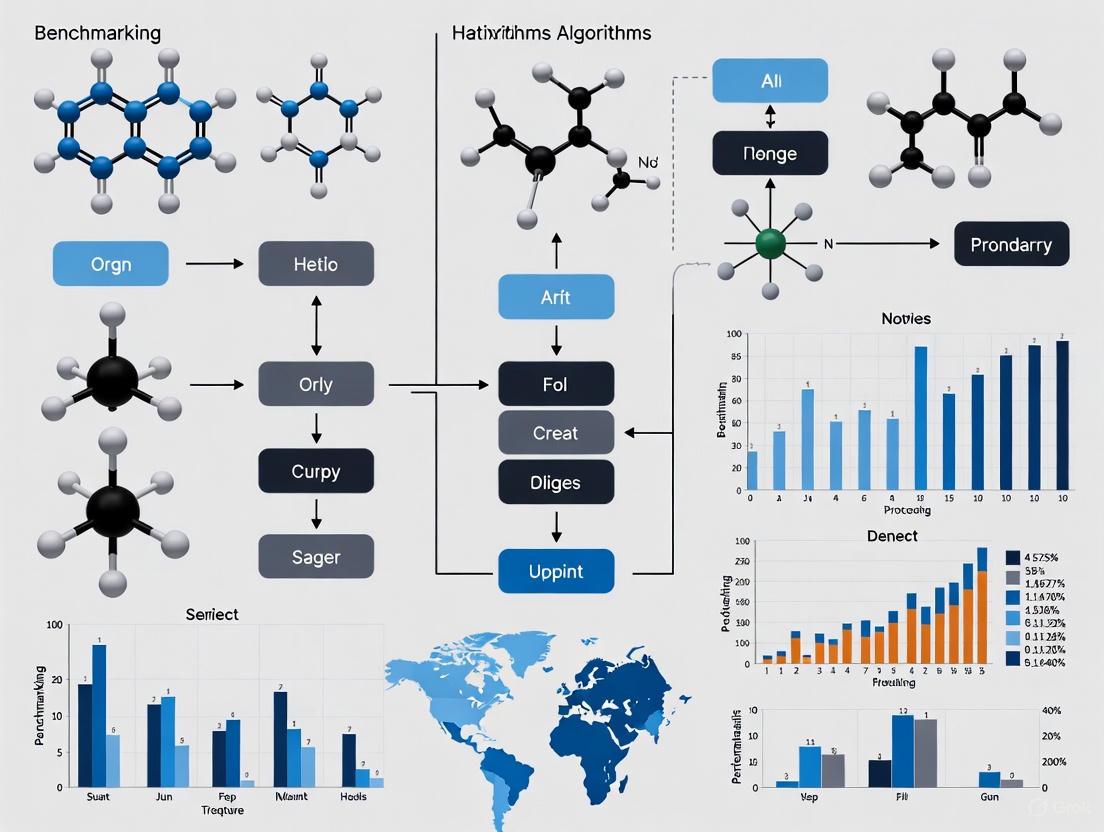

The following diagram illustrates the generalized workflow for iterative screening approaches in discrete chemical space:

Molecular Optimization in Continuous Latent Spaces

Continuous latent space methods employ encoder-decoder frameworks, particularly deep generative models, to transform molecules into continuous vector representations in a lower-dimensional space. This representation facilitates optimization through continuous vector manipulation rather than discrete structural changes [1] [6].

Variational Autoencoders (VAEs) encode input molecules into probabilistic latent distributions then decode sampled points back to molecular structures [6]. This approach ensures a smooth latent space, enabling interpolation between molecules and generation of novel structures.

Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) employ two competing networks: a generator that creates synthetic molecular structures and a discriminator that distinguishes between generated and real molecules [6]. This adversarial training process improves the quality and realism of generated molecules.

Transformer-Based Models leverage self-attention mechanisms to capture complex relationships in molecular structures represented as sequences [6]. Originally developed for natural language processing, transformers effectively handle long-range dependencies in molecular data.

Query-based Molecular Optimization (QMO) is a framework developed by IBM Research that uses a deep generative autoencoder to represent molecular variants combined with a search technique that identifies variants optimized for desired properties [5]. QMO uses external guidance from black-box evaluators (simulations, informatics, experiments, or databases) and implements a novel query-based guided search method based on zeroth-order optimization [5].

The workflow for continuous latent space optimization demonstrates the distinct approach of these methods:

Experimental Benchmarking & Performance Comparison

Performance Metrics and Evaluation Protocols

Robust evaluation of AI molecular optimization methods requires standardized metrics and benchmark tasks. Common quantitative metrics include:

- Success Rate: Percentage of lead molecules for which a method successfully generates optimized compounds satisfying all constraints [5]

- Property Improvement: Magnitude of enhancement in target properties (QED, solubility, binding affinity, etc.)

- Similarity Maintenance: Ability to retain structural similarity to lead molecules, typically measured by Tanimoto similarity of Morgan fingerprints [1]

- Novelty: Generation of structurally novel scaffolds rather than minor modifications of known compounds [3]

- Synthetic Accessibility: Assessment of how readily generated molecules can be synthesized, often measured by SA Score [6]

Standardized benchmark tasks include:

- QED Optimization: Improving Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness from 0.7-0.8 to >0.9 while maintaining similarity >0.4 [1]

- Penalized logP Optimization: Enhancing penalized octanol-water partition coefficient while maintaining structural similarity [1]

- DRD2 Optimization: Improving biological activity against dopamine receptor D2 while preserving similarity [1] [6]

- Binding Affinity Optimization: Enhancing target binding affinity for specific protein targets [5]

- Toxicity Reduction: Lowering predicted toxicity while maintaining antimicrobial activity [5]

Comparative Performance Data

Table 1: Performance Comparison of AI Molecular Optimization Methods on Standard Benchmarks

| Method | Type | QED Optimization Success Rate | Solubility Improvement | Similarity Constraint | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| QMO [5] | Continuous Latent Space | 92.8% | ~30% relative improvement | >0.4 Tanimoto | High success rate, multi-property optimization |

| STONED [1] | Discrete Space (SELFIES) | Not specified | Not specified | Maintained | No training data required |

| MolFinder [1] | Discrete Space (SMILES) | Not specified | Not specified | Maintained | Global and local search |

| GB-GA-P [1] | Discrete Space (Graph) | Not specified | Not specified | Maintained | Multi-objective optimization |

| GCPN [1] | Discrete Space (Graph) | Not specified | Not specified | Maintained | End-to-end graph generation |

| MolDQN [1] | Discrete Space (Graph) | Not specified | Not specified | Maintained | Multi-property optimization |

Table 2: Performance on Real-World Optimization Tasks

| Method | Task | Performance | Experimental Validation |

|---|---|---|---|

| QMO [5] | SARS-CoV-2 Mpro inhibitor binding affinity | Improved binding free energy while maintaining high similarity | In silico validation |

| QMO [5] | Antimicrobial peptide toxicity reduction | 72% success rate in reducing toxicity while maintaining similarity | Agreement with state-of-art toxicity predictors |

| AtomNet [3] | Novel hit identification across 318 targets | 73% success rate vs. 50% for HTS | Physical validation across hundreds of academic labs |

| Iterative Screening [4] | Hit finding across multiple HTS datasets | 70-80% of actives found screening 35-50% of library | Retrospective analysis of PubChem HTS data |

Clinical Translation Success Rates

The ultimate validation of AI-optimized molecules comes from their performance in clinical trials. Recent analysis of clinical pipelines from AI-native biotech companies reveals promising results:

Table 3: Clinical Success Rates of AI-Discovered Molecules

| Trial Phase | AI-Discovered Molecules Success Rate | Historical Industry Average |

|---|---|---|

| Phase I | 80-90% | ~50% |

| Phase II | ~40% | ~40% |

| Phase III | Limited data | ~60% |

This data suggests that AI-discovered molecules show substantially higher success rates in Phase I trials, indicating these approaches are highly capable of generating molecules with excellent drug-like properties and safety profiles [7]. The comparable performance in Phase II trials, while based on limited sample sizes, suggests AI-optimized molecules maintain their therapeutic potential in larger patient populations.

Research Reagent Solutions Toolkit

Table 4: Essential Research Tools for AI Molecular Optimization

| Tool/Category | Specific Examples | Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| Molecular Representations | SMILES, SELFIES, Molecular Graphs | Standardized formats for computational representation of chemical structures | All AI molecular optimization approaches |

| Fingerprint Methods | Morgan Fingerprints, Extended Connectivity Fingerprints | Vector representations capturing molecular features for similarity assessment and machine learning | Similarity calculations, model inputs |

| Property Predictors | QED, SA Score, logP | Computational estimation of key molecular properties without synthesis | Evaluation of generated molecules |

| Benchmark Datasets | PubChem Bioassays, ZINC, ChEMBL | Curated compound libraries with associated activity data | Training and validation of AI models |

| Generative Frameworks | Variational Autoencoders, GANs, Transformers | Deep learning architectures for molecular generation | Continuous latent space methods |

| Optimization Algorithms | Genetic Algorithms, Reinforcement Learning, Zeroth-order Optimization | Search strategies for identifying optimal molecules | Exploration of chemical space |

| Validation Platforms | High-Throughput Screening, Molecular Dynamics Simulations | Experimental and computational validation of predicted compounds | Confirmatory testing of AI-generated hits |

AI-driven molecular optimization methods have demonstrated significant potential for addressing the critical bottlenecks in drug discovery. The experimental data compiled in this review reveals that these approaches can successfully generate optimized molecules with enhanced properties while maintaining structural similarity to lead compounds. Methods operating in continuous latent spaces, such as QMO, have shown particularly strong performance on standard benchmarks with success rates exceeding 90% for drug-likeness optimization [5]. Meanwhile, iterative screening approaches in discrete chemical spaces can identify 70-80% of active compounds while screening only 35-50% of compound libraries [4].

The most compelling validation comes from clinical trial data, which shows AI-discovered molecules achieving substantially higher Phase I success rates (80-90%) compared to historical industry averages (~50%) [7]. This suggests that AI optimization approaches are indeed generating molecules with superior drug-like properties, potentially reducing attrition in early clinical development.

Despite these promising results, challenges remain in the widespread adoption of AI molecular optimization. Data quality and availability represent significant constraints, with reliable AI models depending on high-quality, target-specific datasets [8] [9]. For many targets, generating appropriate training data can be as costly and time-consuming as traditional wet-lab design approaches. Additionally, model interpretability, integration of complex multi-objective constraints, and validation of novel chemical scaffolds present ongoing research challenges.

Future developments will likely focus on overcoming these limitations through improved data sharing initiatives, enhanced model architectures, and tighter integration between computational prediction and experimental validation. As these technologies mature, AI-driven molecular optimization is poised to fundamentally transform drug discovery, potentially compressing development timelines from years to months while increasing the success rates of clinical candidates [1] [5] [7]. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the comparative performance and appropriate application contexts for these AI approaches will be essential for leveraging their full potential in overcoming the persistent bottlenecks of conventional drug discovery.

In the drug discovery pipeline, molecular optimization represents a critical stage following the initial screening of lead compounds [1]. It is formally defined as the process of modifying a given lead molecule to enhance its specific properties while maintaining a required level of structural similarity to the original compound [1] [10]. This process is crucial for refining promising molecules to achieve a better balance of multiple attributes, such as biological activity, metabolic stability, and safety profiles, which are essential for a successful drug [10]. Unlike de novo molecular generation, which designs molecules from scratch, molecular optimization starts from a known structure, thereby shortening the search process for improved candidates and preserving desirable structural features already present in the lead molecule [1].

The core objective is to generate a target molecule y from a source molecule x, such that the properties of y are superior to those of x ((pi(y) \succ pi(x)) for properties i=1,2,…,m), while the structural similarity between x and y, sim(x, y), remains above a defined threshold δ [1]. A frequently used metric for quantifying structural similarity is the Tanimoto similarity of Morgan fingerprints [1]. This similarity constraint ensures the exploration of a focused chemical space around the lead molecule, improving search efficiency and helping to preserve crucial physicochemical and biological properties inherent to the original scaffold [1].

Comparative Analysis of AI-Driven Molecular Optimization Methods

Artificial Intelligence (AI) has revolutionized molecular optimization, offering diverse strategies to navigate the vast chemical space. The table below summarizes the core operational characteristics of major AI-based approaches.

Table 1: Comparison of AI-Driven Molecular Optimization Methods

| Method Category | Key Example(s) | Molecular Representation | Optimization Mechanism | Reported Advantages/Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Reinforcement Learning (RL) | MolDQN [1], GCPN [1] [11] | Molecular Graph | An agent iteratively modifies structures based on rewards from property predictors. | Effective for multi-property optimization; GCPN generates molecules with targeted properties and high validity [11]. |

| Machine Translation | Transformer-based Models [10] | SMILES String | Translates source molecule SMILES into target SMILES, conditioned on desired property changes. | Generates intuitive, small modifications; capable of multi-property optimization (e.g., logD, solubility, clearance) [10]. |

| Graph-based Generative | MolEditRL [12] | Molecular Graph | Discrete graph diffusion pretraining followed by RL fine-tuning with graph constraints. | 74% improvement in editing success rate; uses 98% fewer parameters; superior structural fidelity [12]. |

| Genetic Algorithms (GA) | GB-GA-P [1], STONED [1] | SELFIES, Graph | Applies crossover and mutation operators; selects high-fitness molecules over generations. | Flexible, requires no large training datasets; GB-GA-P enables multi-objective Pareto optimization [1]. |

| Latent Space | JT-VAE [1] [11] | Latent Vector (from Graph) | Bayesian optimization in a continuous latent space learned by a VAE. | Efficient for costly property evaluations (e.g., docking); compresses complex chemical space [1] [11]. |

Performance Metrics and Benchmarking

Rigorous benchmarking is vital for evaluating the real-world utility of optimization algorithms. Beyond standard benchmarks, performance can drop significantly when models encounter novel protein families, highlighting the need for stringent, realistic evaluation protocols [13]. One such protocol involves leaving entire protein superfamilies out of the training data to simulate the discovery of a novel protein family [13].

Key metrics for evaluation include:

- Editing Success Rate: The percentage of generated molecules that successfully achieve the desired property changes while adhering to structural constraints [12].

- Structural Fidelity: Often measured by the Tanimoto similarity of Morgan fingerprints between the source and generated molecule [1]. The Fréchet ChemNet Distance (FCD) is another metric for distributional fidelity [12].

- Property Prediction Accuracy: For models relying on property predictors, their generalization ability is critical. Task-specific architectures that learn from molecular interaction spaces, rather than raw structures, show more reliable generalization [13].

- Sample Efficiency: The number of molecules that must be synthesized or evaluated to identify a clinical candidate. For instance, Exscientia's AI-driven design of a CDK7 inhibitor achieved a candidate after synthesizing only 136 compounds, far fewer than the thousands typically required in traditional workflows [14].

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol 1: Reinforcement Learning with Graph-Based Models (e.g., GCPN, MolDQN)

Objective: To optimize a lead molecule by sequentially modifying its graph structure to maximize a multi-property reward function.

Workflow:

- Problem Formulation: Frame molecular optimization as a Markov Decision Process (MDP). The state is the current molecular graph, an action is a graph modification (e.g., adding/removing a bond, changing an atom type), and the transition dynamics define the resulting graph after an action.

- Reward Design: The reward function is a weighted sum of predicted properties (e.g., bioactivity, drug-likeness QED, synthetic accessibility) and a penalty for structural dissimilarity from the lead molecule [11]. For example:

Reward = w1 * Bioactivity + w2 * QED - w3 * (1 - Tanimoto_similarity). - Agent Training: Train an RL agent (e.g., using a policy gradient method or Q-learning as in MolDQN) to learn a policy that selects graph-modifying actions maximizing the cumulative reward [1] [11]. The agent explores the chemical space by applying actions and learning from the resulting rewards.

- Validation: The top-generated molecules are validated using independent property prediction models or, ideally, through experimental testing.

Diagram 1: Reinforcement Learning Workflow

Protocol 2: Machine Translation with Conditional Transformer

Objective: To translate the string representation (SMILES) of a source molecule into a target molecule's SMILES, guided by a natural language instruction specifying desired property changes.

Workflow:

- Data Preparation: Train on a dataset of Matched Molecular Pairs (MMPs), where pairs of molecules differ by a single, small chemical transformation [10]. For each pair

(X, Y), the input is the concatenation of the source molecule's SMILESXand an encoded property changeZ(e.g., "increase_solubility"). The target output is the SMILES of the transformed moleculeY[10]. - Model Architecture: Use a Transformer model, which relies on a self-attention mechanism to learn relationships between tokens in the input sequence [10].

- Conditional Generation: During training, the model learns the mapping

(X, Z) -> Y. At inference, given a new molecule and a desired property changeZ, the model generates candidate target molecules conditioned on that instruction. - Filtering: Generated SMILES are checked for chemical validity and filtered based on calculated property values and similarity to the source molecule.

Protocol 3: Benchmarking Generalizability for Property Prediction

Objective: To rigorously evaluate a model's ability to predict molecular properties for novel chemical scaffolds, simulating real-world application.

Workflow:

- Dataset Splitting: Instead of a simple random split, use a scaffold split [15]. This method partitions the dataset based on molecular substructures (Bemis-Murcko scaffolds), ensuring that molecules in the training and test sets have distinct core skeletons [15].

- Protein Family Hold-Out: For tasks involving protein targets, a more stringent protocol involves leaving out all data associated with an entire protein superfamily from the training set. The model is then tested on this held-out superfamily to simulate predicting interactions for a novel target [13].

- Model Training & Evaluation: Train the model on the training set and evaluate its performance exclusively on the scaffold- or protein family-held-out test set. This provides a realistic measure of its generalizability [13] [15].

Diagram 2: Generalizability Benchmark Framework

Successful molecular optimization relies on a foundation of curated data, software, and computational resources.

Table 2: Key Research Reagents and Resources for Molecular Optimization

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function in Optimization | Relevance |

|---|---|---|---|

| MolEdit-Instruct Dataset [12] | Dataset | Provides 3 million molecular editing examples with property changes for training and benchmarking instruction-guided models. | Enables robust training of models like MolEditRL for single- and multi-property tasks. |

| Matched Molecular Pairs (MMPs) [10] | Data Structure/Concept | Pairs of molecules differing by a single transformation; used to train models to learn chemist-intuitive edits. | Captures medicinal chemistry intuition for structure-property relationships. |

| SCAGE Model [15] | Pre-trained Model | A self-conformation-aware graph transformer pre-trained on ~5 million compounds for accurate property prediction. | Serves as a high-performance predictor for properties and activity cliffs in optimization loops. |

| Bayesian Optimization (BO) [11] | Algorithm | Efficiently optimizes expensive-to-evaluate functions (e.g., docking scores) in high-dimensional latent or chemical spaces. | Crucial for sample-efficient navigation when direct property evaluation is computationally costly. |

| Tanimoto Similarity [1] | Metric | Quantifies structural similarity between molecules using Morgan fingerprints to enforce constraints during optimization. | The standard metric for ensuring generated molecules retain core features of the lead compound. |

| Open-Source Protein Databases (e.g., PDB, UniProt) [16] | Database | Provide 3D protein structures and sequences for structure-based drug design and generalizability testing. | Essential for creating realistic benchmarks and for target-specific optimization. |

The development of Artificial Intelligence (AI) for molecular optimization represents a paradigm shift in accelerating drug discovery. The reliable benchmarking of these AI models hinges on a core set of quantitative metrics that assess both the chemical properties of generated molecules and their structural similarity to lead compounds. This guide provides a comparative analysis of the key metrics—including Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness (QED), penalized LogP (LogP), Dopamine Receptor D2 (DRD2) activity, and Tanimoto Similarity—that form the foundation of modern AI molecular optimization research. Standardized evaluation is not merely a technical formality; it is the bedrock of reproducible and meaningful progress. Recent studies have revealed that critical flaws in evaluation protocols, such as incorrect valency definitions and inconsistent energy calculations, can significantly mislead the research community by inflating performance metrics [17]. Therefore, a rigorous and chemically accurate understanding of these benchmarks is paramount for objectively comparing model performance and driving the field forward.

Foundational Metrics for Molecular Assessment

The following metrics are essential for evaluating the success of a molecular optimization algorithm, measuring everything from drug-likeness to specific biological activity.

Table 1: Core Molecular Property Metrics for AI Optimization

| Metric | Full Name | Objective in Optimization | Interpretation of Values |

|---|---|---|---|

| QED | Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness | Maximize (0.0 to 1.0) | Values closer to 1.0 indicate a higher probability of drug-likeness based on key physicochemical properties [1]. |

| penalized LogP | Penalized Octanol-Water Partition Coefficient | Maximize | A measure of lipophilicity; the "penalized" version often includes synthetic accessibility or ring penalty adjustments [1]. |

| DRD2 | Dopamine Receptor D2 Activity | Maximize (0.0 to 1.0) | Measures the probability of a molecule being an active binder to the DRD2 target; higher values indicate stronger predicted activity [1]. |

| Tanimoto Similarity | Tanimoto Similarity (on Morgan Fingerprints) | Maintain above a threshold (e.g., > 0.4) | Measures structural similarity between the generated molecule and the original lead compound. Maintains core structural features [1]. |

Experimental Protocols for Benchmarking AI Models

A standardized experimental protocol ensures that comparisons between different AI models are fair and meaningful.

The Molecular Optimization Task Definition

A molecular optimization task is formally defined as follows: Given a lead molecule ( x ), the goal is to generate a molecule ( y ) with enhanced properties ( p1(y), \dots, pm(y) ) such that ( pi(y) \succ pi(x) ) for ( i = 1, 2, \dots, m ), while maintaining a structural similarity ( \text{sim}(x, y) > \delta ), where ( \delta ) is a predefined threshold (commonly 0.4) [1]. This constraint ensures the optimized molecule retains the core scaffold of the lead.

Dataset Curation and Splitting

The choice and preparation of data are critical. Benchmarks like GEOM-drugs are widely used but require careful processing to avoid chemical inaccuracies that can skew results [17]. For property prediction tasks, it is crucial to use rigorous dataset splits, such as Murcko-scaffold splits, which separate molecules based on their core Bemis-Murcko scaffolds. This approach provides a more realistic estimate of a model's ability to generalize to novel chemotypes compared to simple random splits [18].

Evaluation of Generated Molecules

The evaluation of AI-generated molecules involves a multi-faceted approach:

- Property Prediction: The generated molecules ( y ) are evaluated using pre-trained predictive models or computational methods to estimate their QED, LogP, or DRD2 scores.

- Similarity Verification: The Tanimoto similarity between ( y ) and the lead ( x ) is calculated using Morgan fingerprints to ensure the constraint is met [1].

- Chemical Validity Check: It is essential to move beyond basic validity checks. The "molecular stability" metric should be used, which verifies that all atoms in the generated structure have chemically plausible valencies, correcting for common bugs in aromatic bond handling [17].

Diagram 1: Molecular optimization workflow.

Comparative Performance of AI Optimization Models

Different AI paradigms have been applied to molecular optimization, each with strengths and weaknesses. The table below summarizes the performance of representative models on common benchmark tasks.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of AI Molecular Optimization Models

| Model / Approach | Molecular Representation | QED Optimization (Success Rate†) | penalized LogP Optimization (Success Rate†) | DRD2 Optimization (Success Rate†) | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| JODO [17] | 3D Graph | N/A | N/A | N/A | Uses categorical diffusion; high corrected molecule stability (0.940) |

| Megalodon [17] | 3D Graph | N/A | N/A | N/A | High molecular stability (0.957) and validity after chemical correction |

| GCPN [1] | Graph | ~0.7 | ~0.6 | ~0.1 | Reinforcement learning; constructs molecules sequentially |

| MolDQN [1] | Graph | ~0.8 | ~0.7 | ~0.2 | Deep Q-Learning; multi-property optimization |

| STONED [1] | SELFIES | High | High | High | Genetic algorithm; uses SELFIES for guaranteed validity |

| GB-GA-P [1] | Graph | High | High | High | Pareto-based genetic algorithm for multi-objective optimization |

†Success Rate: The fraction of generated molecules that successfully improve the target property while maintaining similarity > 0.4. Exact values are dataset-dependent and should be compared within the same study. Performance can vary based on implementation and evaluation rigor [17] [1].

Advanced Benchmarking Considerations and Emerging Challenges

As the field matures, benchmarking practices are evolving to address more complex and realistic scenarios.

The Critical Need for Chemically Accurate Evaluation

Many published evaluations contain subtle bugs that artificially inflate performance. A primary issue is the miscalculation of molecular stability. One widespread bug counted aromatic bonds as 1 instead of 1.5 towards an atom's valency, creating chemically implausible structures that were incorrectly marked as "stable" [17]. When this bug was fixed, the reported molecular stability for some models dropped significantly, highlighting the importance of using chemically grounded evaluation scripts.

Multi-Objective Optimization and Gradient Conflicts

Real-world drug discovery requires balancing multiple, often competing, objectives. Multi-task learning (MTL) is a promising approach but is often hampered by negative transfer, where updates from one task degrade performance on another. This is often due to gradient conflicts [18] [19]. Advanced frameworks like DeepDTAGen with its FetterGrad algorithm and Adaptive Checkpointing with Specialization (ACS) have been developed to mitigate this issue, leading to more robust and accurate multi-property predictors and generators [18] [19].

Generalization to Out-of-Distribution (OOD) Molecules

A model's ability to generalize to new regions of chemical space (OOD) is a true test of its utility in discovery. The BOOM benchmark has revealed that even state-of-the-art models struggle with OOD generalization, with average OOD error often being three times larger than in-distribution error [20]. This underscores the importance of using rigorous dataset splits and benchmarking OOD performance explicitly.

Diagram 2: A hierarchy of key evaluation metrics.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

Table 3: Key Computational Tools and Datasets for Molecular Optimization Research

| Tool / Resource | Type | Primary Function in Research |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Software Library | Cheminformatics core; used for fingerprint generation (Tanimoto), molecule sanitization, and property calculation [17]. |

| GEOM-drugs | Dataset | A foundational benchmark dataset of drug-like molecules and their 3D conformations for training and evaluating generative models [17]. |

| GNPS / MassBank | Dataset | Public repositories of tandem mass spectrometry data used for developing and benchmarking MS/MS similarity models [21]. |

| GFN2-xTB | Computational Method | A semi-empirical quantum mechanical method used for accurate geometry optimization and energy calculation of generated structures [17]. |

| MoleculeNet | Benchmark Suite | A collection of standardized datasets for molecular property prediction, including Tox21 and SIDER, facilitating fair model comparison [18]. |

The exploration of chemical space, estimated to contain on the order of 10^60 small molecules, represents one of the most significant challenges in modern drug discovery and materials science [22]. This space is not only vast but also extraordinarily heterogeneous, encompassing everything from simple organic molecules to complex organometallics and biomolecules [22]. The traditional approach of relying solely on wet lab experimentation and computationally expensive first-principles simulations has proven incapable of effectively navigating this immense complexity, as the costs become intractable at scale [22]. This limitation has catalyzed the development of artificial intelligence (AI)-driven molecular optimization methods that can operate within implicit chemical spaces—computationally constructed representations that enable efficient exploration and manipulation of molecular structures.

AI-aided molecular optimization methods fundamentally involve two critical steps: (1) the construction of an implicit chemical space, and (2) the implementation of an optimization approach to identify desired molecules within this space [1]. These methods have revolutionized lead optimization workflows, significantly accelerating the development of drug candidates by enhancing molecular properties while maintaining structural similarity to lead compounds [1]. The strategic optimization of unfavorable properties in lead molecules substantially increases their likelihood of success in subsequent preclinical and clinical evaluations, offering tremendous potential for streamlining the entire drug discovery and development pipeline [1].

This guide provides a comprehensive comparison of contemporary approaches to navigating implicit chemical spaces, focusing on their operational paradigms, performance benchmarks, and practical applications in molecular optimization. By examining discrete chemical space exploration, continuous latent space manipulation, and synthesizable chemical space constrained approaches, we aim to provide researchers with a framework for selecting appropriate methodologies based on specific optimization objectives and constraints.

Comparative Analysis of Molecular Optimization Approaches

Performance Benchmarking Across Optimization Paradigms

Molecular optimization approaches can be broadly categorized based on their operational spaces and optimization mechanisms. The table below provides a systematic comparison of representative methods across key performance metrics and characteristics:

Table 1: Comparative Performance of Molecular Optimization Approaches

| Category | Representative Models | Molecular Representation | Optimization Objectives | Key Strengths | Reported Performance |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Iterative Search in Discrete Space | STONED [1] | SELFIES | Multi-property | No training data required; maintains structural similarity | Effective property improvement while preserving similarity >0.4 |

| MolFinder [1] | SMILES | Multi-property | Global and local search via crossover and mutation | Competitive multi-property optimization | |

| GB-GA-P [1] | Graph | Multi-property | Pareto-based multi-objective optimization | Identifies Pareto-optimal molecules | |

| GCPN [1] [11] | Graph | Single-property | Sequential graph-based generation | High chemical validity; targeted property optimization | |

| MolDQN [1] [11] | Graph | Multi-property | Deep Q-learning with property rewards | Effective multi-property optimization with similarity constraints | |

| Deep Learning in Continuous Latent Space | GraphAF [11] | Graph | Single/Multi-property | Autoregressive flow with RL fine-tuning | Efficient sampling and targeted optimization |

| DeepGraphMolGen [11] | Graph | Multi-property | Multi-objective reward for specific binding affinity | Strong target binding with minimized off-target effects | |

| VAE+BO [11] | SMILES/Graph | Single-property | Bayesian optimization in latent space | Sample-efficient for expensive-to-evaluate properties | |

| Synthesizable-Centric Design | SynFormer [23] | Synthetic pathways | Multi-property | Guaranteed synthetic pathway viability | High reconstruction rates; maintained synthetic feasibility during optimization |

| Uncertainty-Aware Optimization | UQ-D-MPNN [24] | Graph | Multi-property | Uncertainty quantification guides exploration | Superior performance on 16 benchmark tasks; robust to distribution shifts |

Experimental Protocols and Evaluation Frameworks

Benchmarking molecular optimization algorithms requires standardized tasks and evaluation metrics to ensure fair comparison across different approaches. Common experimental protocols include:

Similarity-Constrained Property Optimization: A widely adopted benchmark requires improving specific molecular properties (e.g., quantitative estimate of drug-likeness (QED) or penalized logP) while maintaining a structural similarity value larger than a specified threshold (typically Tanimoto similarity >0.4) [1]. This evaluates the ability to navigate local chemical space while enhancing desired characteristics.

Multi-objective Optimization Tasks: These benchmarks require simultaneously optimizing multiple, potentially competing properties, such as improving biological activity against specific targets (e.g., dopamine type 2 receptor) while maintaining drug-likeness and synthetic accessibility [1] [11]. Performance is evaluated using Pareto front analysis to identify optimal trade-offs.

Synthesizability-Focused Evaluation: For methods emphasizing synthetic accessibility, benchmarks assess the proportion of generated molecules with viable synthetic pathways and the model's ability to reconstruct known molecules from synthesizable chemical spaces [23]. The ChEMBL dataset and Enamine REAL Space are commonly used for these evaluations [23].

Out-of-Distribution Generalization: To evaluate robustness, models are tested on molecular scaffolds not encountered during training or optimization, assessing their ability to navigate diverse regions of chemical space beyond their immediate experience [24].

The Tanimoto similarity of Morgan fingerprints serves as the standard metric for structural similarity assessment, calculated as: sim(x,y) = fp(x)·fp(y) / [fp(x)² + fp(y)² - fp(x)·fp(y)], where fp represents the Morgan fingerprints of the molecule [1].

Methodological Approaches to Chemical Space Navigation

Discrete Chemical Space Exploration

Methods operating in discrete chemical spaces employ direct structural modifications based on discrete representations such as SMILES, SELFIES, and molecular graphs [1]. These approaches typically explore chemical space through an iterative process of generating novel molecular structures via structural modifications, then selecting promising molecules for subsequent optimization cycles [1].

Diagram: Discrete Chemical Space Optimization Workflow

Genetic algorithm (GA)-based methods begin with an initial population and generate new molecules through crossover and mutation operations, then select molecules with high fitness to guide the evolutionary process [1]. For instance, STONED generates offspring molecules by applying random mutations on SELFIES strings, effectively finding molecules with improved properties while maintaining structural similarity [1]. In contrast, MolFinder integrates both crossover and mutation in SMILES-based chemical space, enabling comprehensive global and local search capabilities [1].

Reinforcement learning (RL)-based approaches represent another significant category within discrete space optimization. Methods like MolDQN modify molecules iteratively using rewards that integrate desired properties, sometimes incorporating penalties to preserve similarity to a reference structure [11]. The graph convolutional policy network (GCPN) uses RL to sequentially add atoms and bonds, constructing novel molecules with targeted properties while ensuring high chemical validity [1] [11].

Continuous Latent Space Manipulation

Deep learning approaches construct continuous latent representations of molecules through encoder-decoder frameworks, enabling optimization in a differentiable space [1]. These methods transform discrete molecular structures into continuous vector representations, facilitating smooth navigation and interpolation within the learned chemical space.

Diagram: Continuous Latent Space Optimization Framework

Variational autoencoders (VAEs) have been particularly influential in this domain, learning continuous representations of molecules that enable efficient exploration and interpolation [11]. When combined with Bayesian optimization, VAEs can efficiently navigate the latent space to identify regions corresponding to molecules with enhanced properties [11]. For example, Gómez-Bombarelli et al. demonstrated that integrating Bayesian optimization with VAEs enables more efficient exploration of chemical space compared to direct discrete optimization [11].

Diffusion models have emerged as another powerful approach for continuous space optimization. The Guided Diffusion for Inverse Molecular Design (GaUDI) framework combines an equivariant graph neural network for property prediction with a generative diffusion model, achieving 100% validity in generated structures while optimizing for both single and multiple objectives [11]. This approach has demonstrated significant efficacy in designing molecules for organic electronic applications.

Synthesizable Chemical Space Constraint

A critical limitation of many molecular optimization approaches is their tendency to propose molecules that are difficult or impossible to synthesize [23]. To address this challenge, synthesizable-centric methods constrain the design process to focus exclusively on molecules with viable synthetic pathways by generating synthetic routes rather than just molecular structures.

SynFormer represents a significant advancement in this category, employing a generative framework that ensures every generated molecule has a viable synthetic pathway [23]. Unlike traditional molecular generation approaches, SynFormer generates synthetic pathways for molecules using a transformer architecture and diffusion module for building block selection, ensuring synthetic tractability within the limitations of predefined transformation rules and available building blocks [23].

This approach models synthesizable chemical space as encompassing all molecules that can be formed by connecting purchasable molecular building blocks through up to five steps of known chemical transformations [23]. By representing synthetic pathways linearly using postfix notation with reaction tokens and building block tokens, SynFormer enables autoregressive decoding via a scalable transformer architecture while accommodating both linear and convergent synthetic sequences [23].

Uncertainty-Aware Molecular Optimization

The integration of uncertainty quantification (UQ) represents another significant advancement in molecular optimization, particularly for navigating open-ended chemical spaces where conventional machine learning models often struggle due to unreliable predictions for molecules outside the training data distribution [24].

Research from National Taiwan University has demonstrated that incorporating UQ into graph neural network models, specifically directed message passing neural networks (D-MPNNs), significantly improves both the efficiency and robustness of molecular optimization [24]. When coupled with genetic algorithms, these uncertainty-aware models enable flexible and library-free molecular optimization across diverse benchmark tasks reflecting key challenges in organic electronics, reaction engineering, and drug development [24].

Among uncertainty-aware optimization strategies, probabilistic improvement optimization (PIO) has consistently delivered superior performance by leveraging uncertainty estimates to calculate the likelihood that candidate molecules will meet design thresholds, effectively steering the search toward chemically promising regions while avoiding unreliable extrapolations [24].

Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

The experimental and computational research in implicit chemical space navigation relies on several key resources and datasets:

Table 2: Essential Research Resources for Molecular Optimization Studies

| Resource Category | Specific Examples | Function and Application | Key Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|

| Benchmark Datasets | QM9 [11] [22] | Quantum mechanical property prediction | 134k stable small organic molecules with DFT-calculated properties |

| ChEMBL [23] | Drug discovery optimization | Bioactivity data on drug-like molecules with experimental validation | |

| Enamine REAL Space [22] [23] | Synthesizable chemical space exploration | Billions of readily synthesizable molecules via robust reactions | |

| Molecular Representations | SMILES [1] | String-based molecular representation | Linear string notation for molecular structure encoding |

| SELFIES [1] | Robust string representation | 100% valid molecular generation from string manipulations | |

| Molecular Graphs [1] | Graph-structured representation | Atoms as nodes, bonds as edges for GNN-based processing | |

| Evaluation Frameworks | Tartarus [24] | Molecular optimization benchmarking | Diverse tasks for drug discovery and materials science |

| GuacaMol [24] | Generative model benchmarking | Standardized benchmarks for goal-directed molecular generation | |

| Foundation Models | MIST [22] | Molecular property prediction | Transformer-based foundation models for multiple property prediction |

| UMA [25] | Universal atomistic modeling | Neural network potentials trained on diverse molecular datasets | |

| Specialized Tools | FGBench [26] | Functional group-level reasoning | Dataset for FG-based molecular property reasoning in LLMs |

| SynFormer [23] | Synthesizable molecular design | Generative framework for pathway-controlled molecular design |

The comparative analysis presented in this guide demonstrates that the optimal approach for navigating implicit chemical spaces depends significantly on the specific optimization objectives and constraints. Discrete space methods offer advantages in interpretability and direct structural control, while continuous latent space approaches enable smoother optimization and interpolation. The emerging paradigms of synthesizable-constrained and uncertainty-aware optimization address critical limitations in practical deployment, ensuring generated molecules are both synthetically feasible and robustly optimized.

As the field advances, the integration of these approaches with increasingly sophisticated foundation models like MIST [22] and UMA [25] promises to further enhance our ability to navigate chemical space efficiently. These developments, coupled with standardized benchmarking frameworks and specialized resources for functional group-level reasoning [26], are paving the way for more reliable and effective AI-assisted molecular discovery across pharmaceutical development and materials science applications.

The application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) in molecular optimization represents a paradigm shift in drug discovery, compressing timelines that traditionally spanned years into weeks or months [14] [27]. AI-driven platforms now leverage machine learning and generative models to navigate the vast chemical space of an estimated 10⁶⁰ drug-like molecules, a task practically impossible for human researchers alone [27]. However, as the number of AI solutions proliferates, the field faces a critical challenge: objectively evaluating and comparing the performance of these diverse algorithms and platforms. Without standardized assessment, claims of superiority remain unverifiable, hindering scientific progress and informed decision-making for drug development professionals.

Benchmarking platforms provide the essential infrastructure to address this challenge. They establish standardized tasks, datasets, and evaluation metrics to impartially measure performance across different AI approaches. This objective comparison is vital for tracking field-wide progress, identifying truly state-of-the-art methods, and guiding future research and development efforts. As noted by industry leaders, in the rigorous field of biotech, concrete benchmarks matter more than claims; the ultimate measure of success is the ability to produce viable drug candidates [28]. This guide provides a comparative analysis of current AI molecular optimization platforms and the benchmarking frameworks that are establishing the state-of-the-art in this rapidly evolving field.

Comparative Analysis of Leading AI Molecular Optimization Platforms

The landscape of AI-driven drug discovery features a variety of platforms, each employing distinct technological approaches. The table below synthesizes the key platforms, their core technologies, and their documented performance on molecular optimization tasks.

Table 1: Leading AI Drug Discovery Platforms and Their Optimization Approaches

| Platform/ Company | Core AI Technology | Optimization Approach | Reported Performance / Clinical Stage | Primary Focus |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MultiMol [29] | Collaborative LLM System (Data-driven Worker & Research Agent) | Multi-objective molecular optimization guided by literature and data | 82.3% success rate on multi-objective optimization tasks [29] | Multi-property molecular optimization |

| Exscientia [14] | Generative AI & Centaur Chemist | End-to-end platform integrating target selection to lead optimization | Clinical candidate with only 136 synthesized compounds (vs. thousands typically) [14] | Small-molecule drug design |

| Insilico Medicine [14] [30] | Generative AI (PandaOmics, Chemistry42) | End-to-end pipeline from target discovery to clinical prediction | AI-designed drug progressed from target to Phase I trials in 18 months [14] | Full-stack drug discovery and development |

| Recursion Pharmaceuticals [14] | Phenomics & LOWE LLM | AI-driven analysis of biological and chemical datasets | Leverages massive proprietary dataset for target deconvolution [14] [30] | Target identification and compound screening |

| BenevolentAI [14] [30] | Knowledge Graph & Machine Learning | Target identification and drug repurposing from scientific literature | Identified potential COVID-19 treatment through AI-driven analysis [30] [31] | Target discovery and validation |

| Atomwise [30] [31] | AtomNet (Deep Learning for Structure) | Predicts drug-target interactions for virtual screening | Screened billions of virtual compounds; nominated a TYK2 inhibitor candidate [31] [32] | Hit discovery and lead optimization |

These platforms demonstrate the two primary paradigms in AI-driven molecular optimization: those operating in discrete chemical spaces using direct structural modifications (e.g., genetic algorithms on SMILES strings) and those operating in continuous latent spaces using encoder-decoder frameworks to transform molecules into vectors for optimization [1]. More recently, Large Language Models (LLMs) have emerged as a powerful third approach, leveraging their broad domain knowledge and reasoning capabilities for tasks like molecule editing and optimization [29] [33].

Benchmarking Frameworks and Experimental Protocols

To objectively evaluate the capabilities of different AI models, the research community has developed specialized benchmarks. These frameworks standardize tasks and metrics, enabling direct and meaningful comparisons.

Key Benchmarking Platforms and Metrics

Table 2: AI Molecular Optimization Benchmarking Frameworks

| Benchmark Name | Primary Focus | Core Evaluation Tasks | Key Metrics | Notable Findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| TOMG-Bench (Text-based Open Molecule Generation) [33] | Evaluating LLMs on molecule generation | 1. Molecule Editing2. Property Optimization3. Novel Molecule Generation | Validity, Novelty, Success Rate | Leading proprietary LLMs like Claude-3.5 show promise but struggle with consistent validity. Larger model size generally correlates with better performance [33]. |

| Specialized Model Benchmarks (e.g., for MultiMol) [29] | Evaluating specialized AI models on multi-objective optimization | Simultaneous optimization of multiple molecular properties (e.g., LogP, QED, selectivity) | Success Rate, Property Improvement, Scaffold Similarity | MultiMol achieved a 66.49% average success rate across 6 multi-objective tasks, significantly outperforming baseline methods (~10% success rate) [29]. |

Detailed Experimental Protocol for Multi-Objective Molecular Optimization

The following workflow details the experimental methodology used by advanced systems like MultiMol, which exemplifies a modern, rigorous approach to AI-driven molecular optimization [29].

Figure 1. Collaborative AI Workflow for Molecular Optimization. This diagram illustrates the two-agent synergy system, where a data-driven worker generates candidates and a research agent provides literature-based filtering.

Step 1: Problem Formulation and Input Preparation The process begins with a lead molecule that requires property enhancement. Using a toolkit like RDKit, the molecule's core scaffold (its molecular framework) and key property values (e.g., LogP, Quantitative Estimate of Drug-likeness - QED) are extracted from its SMILES string [29] [1]. The optimization objectives are defined, such as "reduce LogP by X and increase hydrogen bond acceptor count by Y."

Step 2: Candidate Generation via Data-Driven Worker Agent A fine-tuned LLM, the Worker Agent, is tasked with generating novel molecular structures. The input to this agent is the scaffold SMILES and the adjusted target property values. The model is specifically trained to generate molecules that satisfy these new property specifications while preserving the original molecular scaffold, which is crucial for maintaining the core biological activity [29] [1]. This step produces a diverse pool of candidate molecules.

Step 3: Literature-Guided Research and Filtering Concurrently, a second LLM, the Research Agent, performs automated searches of biomedical literature (e.g., via web search APIs) to identify molecular characteristics associated with the desired properties [29]. For instance, if the goal is to reduce LogP, the agent might find that polar groups or specific electronegative atoms are correlated with lower LogP values. The agent then uses these insights to construct a simple, interpretable filtering function.

Step 4: Ranking and Selection The candidate molecules from the Worker Agent are evaluated against the filtering function derived in Step 3. Molecules possessing the literature-identified desirable characteristics are ranked higher. The top-ranked molecules, which successfully meet the multi-objective criteria and are backed by scientific evidence, are selected as the final optimized outputs [29].

Performance Results and State-of-the-Art Establishment

Quantitative results from standardized benchmarks are the ultimate measure of progress in AI molecular optimization. The performance of various methods on critical tasks is summarized below.

Table 3: Comparative Performance on Multi-Objective Optimization Tasks

| AI Model / Method | Average Success Rate (Multi-Objective Tasks) | Key Strengths | Limitations / Challenges |

|---|---|---|---|

| MultiMol [29] | 82.30% | Effective collaboration between data and literature agents; high success in complex tasks. | Requires robust information retrieval and integration. |

| Strongest Baseline Methods (Pre-MultiMol) [29] | 27.50% | Established reliability on specific, narrower tasks. | Poor performance on complex multi-objective optimization. |

| Other AI Platforms (e.g., Exscientia, Insilico) [14] | Not publicly benchmarked on standard tasks | Demonstrated real-world impact with drugs entering clinical trials. | Difficult to compare algorithm performance directly due to proprietary platforms and lack of standardized reporting. |

| Leading Proprietary LLMs (e.g., Claude-3.5) [33] | Shows promise but struggles with consistency on TOMG-Bench | Leverages broad knowledge and reasoning from pre-training. | Often generates chemically invalid molecules; requires specialized tuning. |

These results clearly demonstrate a significant performance gap between the previous generation of methods and newer, more sophisticated systems like MultiMol. The over 80% success rate on multi-objective tasks represents a qualitative leap forward. However, benchmarks like TOMG-Bench also reveal a crucial finding for the field: general-purpose LLMs, without specialized training, are not yet reliable for direct molecular generation, as they frequently produce invalid structures [33]. This underscores the necessity of benchmarks to separate hype from reality.

Real-World Validation Case Studies

Beyond academic benchmarks, real-world application validates the practical utility of these AI models. For example:

- Saquinavir Bioavailability Improvement: MultiMol was successfully applied to optimize Saquinavir, an HIV-1 protease inhibitor, improving its bioavailability while preserving its binding affinity [29].

- XAC Selectivity Enhancement: The platform was also used to enhance the selectivity of XAC, a promiscuous ligand, successfully biasing its binding affinity towards the A1R receptor over the A2AR receptor [29].

- Efficiency in Clinical Candidate Identification: Exscientia reported identifying a clinical candidate CDK7 inhibitor after synthesizing only 136 compounds, a small fraction of the thousands typically required in traditional medicinal chemistry workflows [14].

Essential Research Reagent Solutions for AI Molecular Optimization

The experimental validation of AI-generated molecules relies on a suite of computational "reagents" and tools. The following table details these essential components.

Table 4: Key Research Reagent Solutions for Computational Validation

| Research Reagent / Tool | Function in the Workflow | Application in AI Molecular Optimization |

|---|---|---|

| RDKit [29] [1] | Cheminformatics Toolkit | Used for scaffold extraction, molecular descriptor calculation, fingerprint generation (e.g., Morgan fingerprints), and molecular similarity calculations (e.g., Tanimoto similarity). |

| SELFIES (Self-Referencing Embedded Strings) [1] | Molecular Representation | A string-based molecular representation that guarantees 100% chemical validity when parsed, used in methods like STONED for robust molecular generation. |

| Morgan Fingerprints (Circular Fingerprints) [1] | Molecular Similarity Measurement | A method for encoding the structure of a molecule into a bitstring. Critical for calculating Tanimoto similarity to ensure optimized molecules retain structural similarity to the lead compound. |

| TOMG-Bench [33] | Benchmarking Framework | Provides a standardized set of tasks (Molecule Editing, Property Optimization, Novel Generation) to evaluate and compare the performance of different LLMs on molecule generation. |

| OpenMolIns [33] | Instruction-Tuning Dataset | A specialized dataset created to improve LLMs' performance on open-ended molecule generation tasks, addressing the shortcomings of general molecule-text datasets. |

Benchmarking platforms are the cornerstone of rigorous scientific progress in AI-driven molecular optimization. They move the field beyond theoretical promises and marketing claims by providing standardized, objective measures of performance. As the results from frameworks like TOMG-Bench and the demonstrated success of platforms like MultiMol show, the state-of-the-art is rapidly advancing, with modern systems achieving remarkable success rates on complex, multi-property optimization tasks.

The establishment of these benchmarks reveals clear future directions: the need for more specialized training data, the continued importance of integrating domain knowledge, and the critical challenge of ensuring that AI-generated molecules are not only optimal in silico but also viable in the wet lab and the clinic. For researchers and drug development professionals, leveraging these benchmarks is essential for selecting tools, guiding development, and ultimately, accelerating the discovery of new therapeutics.

AI Architectures in Action: A Taxonomy of Molecular Optimization Algorithms

In the field of AI-driven molecular optimization, iterative search in discrete chemical space represents a foundational paradigm for improving lead compounds in drug discovery. This approach operates directly on discrete molecular representations—such as SMILES strings, SELFIES, or molecular graphs—to navigate the vast combinatorial landscape of possible drug-like molecules [1]. Within this paradigm, Genetic Algorithms (GAs) and Reinforcement Learning (RL) have emerged as two dominant, yet methodologically distinct, strategies. This guide provides an objective comparison of these approaches, detailing their operational frameworks, relative performance on benchmark tasks, and practical implementation considerations for researchers and drug development professionals.

The critical importance of molecular optimization stems from its role in refining lead compounds to enhance key properties—such as biological activity, solubility, or metabolic stability—while maintaining structural similarity to preserve desired characteristics [1]. As the chemical space is estimated to contain up to 10^60 drug-like molecules [34], efficient navigation strategies are essential. GAs bring evolutionary operations to this challenge, while RL approaches it as a sequential decision-making problem, each with distinct strengths and limitations for real-world drug discovery applications.

Methodological Frameworks

Genetic Algorithm Approaches

Genetic Algorithms for molecular optimization emulate natural selection principles, maintaining a population of candidate molecules that evolve through iterative application of genetic operators [1]. The typical workflow (illustrated in Figure 1) begins with population initialization, proceeds through fitness evaluation, and then applies selection, crossover, and mutation operations to generate improved offspring for subsequent generations.

Key implementations include:

- STONED: Utilizes SELFIES representations and applies random mutations to generate offspring, maintaining structural similarity while exploring local chemical space [1].

- MolFinder: Operates on SMILES strings and incorporates both crossover and mutation operations, enabling a balance of global and local search capabilities [1].

- GB-GA-P: Employs molecular graph representations and Pareto-based genetic algorithms to facilitate multi-objective optimization without requiring predefined property weights [1].

A significant advantage of GA-based methods is their flexibility and robustness, as they can explore chemical space effectively without requiring extensive training datasets [1]. However, their performance is highly dependent on population size and the number of evolutionary generations, with repeated property evaluations potentially becoming computationally expensive [1].

Reinforcement Learning Approaches

Reinforcement Learning formulates molecular optimization as a Markov Decision Process where an agent learns to perform structural modifications through trial-and-error interactions with a chemical environment [1]. The agent, typically a neural network, learns a policy that maximizes cumulative reward, which is defined by the desired molecular properties.

Notable RL frameworks include:

- GCPN: A graph-based model that formulates molecular generation as a Markov Decision Process, using policy gradients to optimize properties [1].

- MolDQN: Implements deep Q-networks on molecular graphs to handle both single and multi-property optimization tasks [1].

RL methods demonstrate particular strength in learning complex policies for sequential molecular modification and can leverage sophisticated neural architectures. However, they often require careful reward engineering and may need substantial environment interactions to learn effective policies.

Comparative Performance Analysis

Benchmark Tasks and Evaluation Metrics

Standardized benchmarks enable direct comparison between GA and RL approaches. Commonly used tasks include [1]:

- Penalized LogP Optimization: Improving the penalized octanol-water partition coefficient while maintaining structural similarity (Tanimoto similarity > 0.4) to the starting molecule.

- DRD2 Activity Optimization: Enhancing biological activity against the dopamine type 2 receptor while preserving structural similarity.

- QED Optimization: Improving quantitative estimate of drug-likeness from moderate (0.7-0.8) to high (>0.9) levels with similarity constraints.

Performance is typically evaluated using:

- Property improvement magnitude: The degree of enhancement achieved for the target property.

- Similarity maintenance: Ability to retain structural features of the lead compound.

- Computational efficiency: Number of evaluations or time required to identify optimized compounds.

- Success rate: Percentage of starting molecules for which satisfactory optimizations are found.

Table 1: Performance Comparison on Benchmark Tasks

| Method | Representation | Penalized LogP Improvement | Similarity Constraint | Success Rate | Sample Efficiency |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| STONED | SELFIES | ++ | 0.4 | Medium | High |

| MolFinder | SMILES | +++ | 0.4 | High | Medium |

| GB-GA-P | Graph | +++ | 0.4 | High | Medium |

| GCPN | Graph | ++++ | 0.4 | Medium | Low |

| MolDQN | Graph | ++++ | 0.4 | Medium | Low |

Table 2: Method Characteristics and Applicability

| Method | Multi-objective Support | Training Data Requirements | Hyperparameter Sensitivity | Interpretability |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| STONED | Limited | Low | Low | Medium |

| MolFinder | Good | Low | Medium | Medium |

| GB-GA-P | Excellent | Low | High | High |

| GCPN | Limited | High | High | Low |

| MolDQN | Good | High | High | Low |

Synergistic Approaches

Recent research explores hybrid models that leverage complementary strengths of both paradigms. The Evolutionary Augmentation Mechanism (EAM) synergizes the learning efficiency of deep reinforcement learning with the global search capabilities of genetic algorithms [35]. This framework generates solutions from a learned policy and refines them through domain-specific genetic operations, with evolved solutions selectively reinjected into policy training to enhance exploration and accelerate convergence [35].

Another emerging trend involves using GA-generated demonstrations to enhance RL training. In industrially-inspired environments, incorporating GA-generated expert demonstrations into RL replay buffers and as warm-start trajectories has been shown to significantly improve policy learning and accelerate training convergence [36].

Experimental Protocols and Workflows

Genetic Algorithm Implementation

A standard GA protocol for molecular optimization includes these key stages [1]:

Population Initialization: Generate initial population of molecules, typically through random sampling or based on known lead compounds.

Fitness Evaluation: Calculate fitness scores for each molecule based on target properties and similarity constraints.

Selection: Identify promising molecules for reproduction using tournament or roulette wheel selection.

Genetic Operations:

- Crossover: Combine substructures from parent molecules to create novel offspring.

- Mutation: Apply stochastic modifications to molecular structures (e.g., atom or bond changes).

Population Update: Replace least-fit individuals with new offspring while maintaining population diversity.

Diagram Title: Genetic Algorithm Workflow

Reinforcement Learning Protocol

A typical RL framework for molecular optimization implements these components [1]:

State Representation: Encode molecular structure as input state (e.g., graph, SMILES, or fingerprint representation).

Action Space Definition: Define valid structural modifications (e.g., add/remove atoms or bonds, modify functional groups).

Reward Function: Design reward signal based on property improvement and similarity constraints.

Policy Learning: Train policy network using RL algorithms (e.g., policy gradients, Q-learning) to maximize cumulative reward.

Validation: Assess generated molecules using external validation metrics and expert review.

Diagram Title: Reinforcement Learning Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Tools

| Tool/Resource | Type | Function | Example Applications |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular manipulation, fingerprint generation, similarity calculation | All molecular representation and analysis tasks [37] |

| SELFIES | Molecular Representation | Robust string-based molecular encoding that guarantees validity | STONED algorithm for mutation operations [1] |

| Morgan Fingerprints | Molecular Descriptor | Circular fingerprints for similarity assessment | Tanimoto similarity calculation [1] |

| ZINC Database | Compound Library | Source of commercially available compounds for validation | Benchmarking and control experiments [37] |

| RosettaLigand | Docking Software | Flexible protein-ligand docking for binding affinity estimation | Fitness evaluation in evolutionary algorithms [34] |

| OpenAI Gym | RL Environment | Framework for implementing custom RL environments | Molecular optimization environments [1] |

Genetic Algorithms and Reinforcement Learning offer complementary approaches to iterative search in discrete molecular space, each with distinctive operational characteristics and performance profiles. GA methods generally excel in scenarios with limited training data, require minimal domain knowledge for implementation, and provide more interpretable optimization pathways. RL approaches demonstrate stronger performance on complex benchmark tasks but demand greater computational resources and careful reward engineering.

The emerging trend of hybrid algorithms—such as the Evolutionary Augmentation Mechanism and GA-assisted RL training—represents a promising research direction that leverages the respective strengths of both paradigms [35] [36]. For drug discovery researchers, selection between these approaches should be guided by specific project constraints, including available data resources, computational budget, property optimization complexity, and the need for interpretability in the optimization process.

The exploration of chemical space for molecular optimization is a fundamental challenge in drug discovery and materials science. Traditional methods, which often rely on discrete molecular representations, face limitations in navigating the vast and complex landscape of possible compounds. The paradigm of continuous latent space learning, enabled by deep generative models, has emerged as a transformative approach. By representing molecules as vectors in a continuous, differentiable space, these models allow for systematic interpolation, optimization, and generation of novel molecular structures with desired properties.

This guide provides a comparative analysis of three dominant deep learning architectures operating in continuous latent space—Variational Autoencoders (VAEs), Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs), and Diffusion Models—within the specific context of benchmarking AI molecular optimization algorithms. For researchers and drug development professionals, understanding the performance characteristics, experimental protocols, and trade-offs of these models is critical for selecting the appropriate tool for a given molecular optimization task.

Model Architectures and Comparative Performance

The core of molecular optimization in continuous latent space involves an encoder-decoder framework. An encoder network maps a discrete molecular representation (e.g., a SMILES string or molecular graph) into a latent vector z. Optimization—such as improving drug-likeness (QED) or biological activity—is then performed within this continuous space. Finally, a decoder network maps the optimized latent vector back into a discrete, valid molecular structure [38]. The choice of generative model underpinning this framework significantly influences the optimization outcome.

The following table summarizes the core operational principles of each model in the context of molecular optimization.

Table 1: Core Architectures for Molecular Optimization in Latent Space

| Model | Core Mechanism | Molecular Optimization Workflow | Key Components |

|---|---|---|---|

| Variational Autoencoder (VAE) | Probabilistic encoder-learns a distribution over the latent space, enabling generation by sampling from this distribution [39] [40]. | 1. Encoder maps molecule to latent distribution parameters (μ, σ).2. A point z is sampled from the distribution.3. Decoder reconstructs the molecule from z [38]. |

Encoder network, latent distribution (mean μ, variance σ²), decoder network, Kullback-Leibler (KL) divergence loss [39]. |

| Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) | Adversarial training between a Generator (creates molecules) and a Discriminator (evaluates authenticity) [41] [39]. | 1. Generator transforms a random noise vector z into a molecule.2. Discriminator evaluates how "real" the generated molecule is.3. Both networks improve adversarially [42] [39]. |

Generator network, discriminator network, adversarial loss functions [39]. |