Advances in Computational Modeling for Molecular Property Prediction: From Foundation Models to Real-World Applications

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of computational molecular property prediction, a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and materials science.

Advances in Computational Modeling for Molecular Property Prediction: From Foundation Models to Real-World Applications

Abstract

This article provides a comprehensive overview of the rapidly evolving field of computational molecular property prediction, a cornerstone of modern drug discovery and materials science. We explore the foundational principles of molecular representation, from traditional descriptors to modern graph-based and sequence-based models. The review systematically covers cutting-edge methodological advances, including foundation models, multi-view architectures, and high-throughput computing frameworks. A dedicated troubleshooting section addresses critical challenges such as data heterogeneity, model interpretability, and optimization strategies. Finally, we present rigorous validation approaches and comparative analyses across benchmark datasets, offering researchers and drug development professionals practical insights for implementing these technologies while highlighting emerging trends and future directions for the field.

Molecular Representations and Core Concepts: Building Blocks for Predictive Modeling

Traditional molecular representations are foundational to computational chemistry and drug discovery, serving as the critical first step in quantitative structure-activity relationship (QSAR) models and machine learning-based property prediction [1]. These representations—including fixed descriptors, structural fingerprints, and SMILES strings—transform complex molecular structures into mathematically tractable formats, enabling rapid virtual screening and biological activity prediction [2] [3]. Despite the emergence of deep learning approaches that learn features directly from molecular graphs or line notations, traditional representations remain widely valued for their interpretability, computational efficiency, and strong performance across diverse tasks, particularly when training data is limited [2] [4]. This application note provides a comprehensive overview of these fundamental representation methods, detailing their underlying principles, comparative performance characteristics, and standardized protocols for their implementation in molecular property prediction research.

Types of Traditional Molecular Representations

Fixed Molecular Descriptors

Fixed molecular descriptors encompass experimentally measured or theoretically calculated physicochemical properties that provide a quantitative profile of a compound's characteristics [4]. These descriptors are typically categorized by the level of structural information they encode:

- 0D Descriptors: Basic molecular formula information including atom counts, molecular weight, and formal charge [4].

- 1D Descriptors: Whole-molecule properties such as molar refractivity (MolMR), partition coefficient (MolLogP), and topological polar surface area (PSA) [4].

- 2D Descriptors: Topological descriptors derived from molecular connectivity, including molecular connectivity indices, Wiener index, and Balaban index [4].

Comprehensive descriptor sets such as the RDKit 2D descriptors provide approximately 200 molecular features that can be rapidly computed, offering a rich numerical representation for machine learning algorithms [4]. A subset of 11 drug-likeness PhysChem descriptors is frequently used as a baseline representation for pharmaceutical applications (Table 1) [4].

Molecular Fingerprints

Molecular fingerprints encode molecular structures as fixed-length bit or count vectors, with different algorithms designed to capture specific structural aspects [2] [1]. The choice of fingerprint significantly impacts model performance and should be aligned with the specific research application [1].

Table 1: Classification and Characteristics of Major Fingerprint Types

| Fingerprint Type | Representative Examples | Structural Basis | Key Parameters | Common Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dictionary-Based (Structural Keys) | MACCS, PubChem | Predefined structural fragments | Fixed size (e.g., 166 bits for MACCS) | Rapid substructure searching, database filtering [2] [5] |

| Circular | ECFP4, ECFP6, FCFP | Circular atom environments | Radius (2 for ECFP4, 3 for ECFP6), vector size (1024, 2048) | Structure-activity modeling, similarity assessment [2] [4] |

| Path-Based (Topological) | RDKit, Daylight, Atom Pairs | Linear paths through molecular graph | minPath, maxPath (typically 1-7 bonds) | Similarity searching, scaffold hopping [2] [1] |

| Pharmacophore | 3-point PP, 4-point PP | 3D functional features | Feature types (H-bond donor/acceptor, etc.) | Target-based screening, binding mode prediction [1] |

| Protein-Ligand Interaction (PLIFP) | SIFt, SPLIF | Protein-ligand interaction patterns | Atom types, geometric criteria | Binding affinity prediction, binding mode analysis [1] |

SMILES Strings

The Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) represents molecular structures as linear strings using ASCII characters [5] [3]. SMILES utilizes simple grammar rules: atoms are represented by atomic symbols; bonds by '-', '=', '#' for single, double, and triple bonds respectively (single and aromatic bonds are often omitted); branches are enclosed in parentheses; and ring closures are indicated by numerical suffixes [5]. A significant limitation of SMILES is that a single molecule can generate multiple valid strings due to different atom ordering, though canonicalization algorithms can produce a unique representation for each structure [4] [5]. Despite their widespread use, SMILES strings present challenges for natural language processing algorithms due to their fragile grammar, where single-character errors can render strings invalid [5].

Comparative Performance in Molecular Property Prediction

Benchmarking Studies

Recent large-scale benchmarking studies have systematically evaluated the performance of traditional representations against learned representations across diverse molecular property prediction tasks. Key findings from these evaluations are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Molecular Representations in Property Prediction

| Representation Type | Representative Examples | Data-Rich Regimes | Low-Data Regimes | Interpretability | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed Descriptors | RDKit 2D, PhysChem | Moderate | Strong | High | Limited feature learning, manual engineering [4] |

| Molecular Fingerprints | ECFP4, ECFP6, MACCS | Strong | Strong | Moderate to High | Lossy transformation, fixed feature set [2] [4] |

| SMILES Strings | Canonical SMILES | Variable | Moderate | Low | Fragile grammar, tokenization issues [4] [5] |

| Learned Representations | GNNs, Transformers | Strong to Superior | Weaker | Low | Data hunger, computational intensity [2] [4] |

A comprehensive study evaluating 62,820 models across multiple datasets revealed that representation learning models exhibit limited performance advantages in most molecular property prediction tasks when compared to traditional fingerprints and descriptors [4]. The study emphasized that dataset characteristics, particularly size and label distribution, significantly influence the optimal choice of representation. In scenarios with limited training data—common in early drug discovery—traditional representations frequently outperform learned approaches [4].

For drug sensitivity prediction in cancer cell lines, benchmarking studies have demonstrated that the predictive performance of end-to-end deep learning models is comparable to, and occasionally surpasses, that of models trained on molecular fingerprints [2]. However, ensemble approaches that combine multiple representation methods often achieve superior performance, leveraging complementary strengths of different representations [2].

Key Factors Influencing Representation Performance

- Dataset Size: Traditional fingerprints generally outperform learned representations in low-data scenarios, while learned representations show stronger performance with larger datasets (>10,000 compounds) [2] [4].

- Task Complexity: For predicting simple molecular descriptors, traditional representations show competitive performance, while learned representations may excel at capturing complex, non-linear structure-property relationships [4].

- Activity Cliffs: Molecular pairs with high structural similarity but large property differences significantly challenge all representation methods, though circular fingerprints like ECFP often demonstrate greater robustness [4].

- Representational Consistency: Unlike SMILES strings which can have multiple valid representations for a single molecule, fingerprints and descriptors provide consistent representations, improving model stability [5].

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Generating Molecular Fingerprints for QSAR Modeling

Purpose: To standardize the generation of molecular fingerprints for building robust QSAR models for biological activity prediction.

Materials:

- Chemical Dataset: Compounds with associated biological activity data (e.g., IC₅₀, Ki)

- Software: RDKit (v2020.09.1 or later) or equivalent cheminformatics toolkit

- Computing Environment: Python 3.7+ with pandas, numpy, and scikit-learn

Procedure:

- Data Preparation:

- Obtain canonical SMILES for all compounds using RDKit's

Chem.MolToSmiles()function withisomericSmiles=Truefor stereochemistry awareness. - Remove duplicates and invalid structures using the ChEMBL Structure Pipeline or equivalent [2].

- Obtain canonical SMILES for all compounds using RDKit's

Fingerprint Generation:

- ECFP Generation:

- Use

rdkit.Chem.rdFingerprintGenerator.GetMorganGenerator(radius=2, fpSize=1024)for ECFP4 - Use

radius=3for ECFP6 - Set

useFeatures=Falsefor ECFP,Truefor FCFP

- Use

- MACCS Keys Generation:

- Use

rdkit.Chem.rdFingerprintGenerator.GetMACCSKeysGenerator()

- Use

- Path-Based Fingerprints:

- For RDKit fingerprints:

rdkit.Chem.rdFingerprintGenerator.GetRDKitFPGenerator(minPath=1, maxPath=7, fpSize=1024) - For AtomPair fingerprints:

rdkit.Chem.rdFingerprintGenerator.GetAtomPairGenerator(minDistance=1, maxDistance=30, fpSize=1024)

- For RDKit fingerprints:

- ECFP Generation:

Model Training & Validation:

Troubleshooting:

- For imbalanced datasets, use stratified splitting or appropriate weighting strategies.

- If model performance is poor, try combining multiple fingerprint types or incorporating molecular descriptors.

Protocol 2: Reconstruction of Molecular Representations from Fingerprints

Purpose: To convert structural fingerprints back to molecular representations, enabling interpretation and visualization of important structural features.

Materials:

- Input: Precomputed molecular fingerprints (ECFP, MACCS, etc.)

- Software: RDKit, Transformer models for fingerprint decoding [5]

- Reference Database: Chemical database for structural matching (e.g., PubChem, ChEMBL)

Procedure:

- Fingerprint Decoding:

- For dictionary-based fingerprints (MACCS), map set bits to corresponding structural patterns using the predefined key dictionary.

- For circular fingerprints (ECFP), identify the corresponding molecular substructures using the hashing function inversion where possible.

Structure Reconstruction:

- Neural Translation Approach: Utilize transformer-based models trained on fingerprint-SMILES pairs to decode fingerprints to SMILES representations [5].

- Genetic Algorithm Approach: Apply evolutionary algorithms to generate molecular structures that match target fingerprint patterns [5].

- Database Mining: Screen chemical databases for compounds with similar fingerprint patterns to identify structural matches.

Validation:

- Verify reconstructed structures by comparing generated fingerprints with original fingerprints.

- Assess chemical validity using RDKit's structure validation tools.

- For novel structures, verify synthetic accessibility using retrosynthesis tools.

Performance Metrics:

- Reconstruction success rate (typically 58-69% for ECFP to SMILES conversion) [5]

- Structural similarity between original and reconstructed molecules

- Computational efficiency (time per reconstruction)

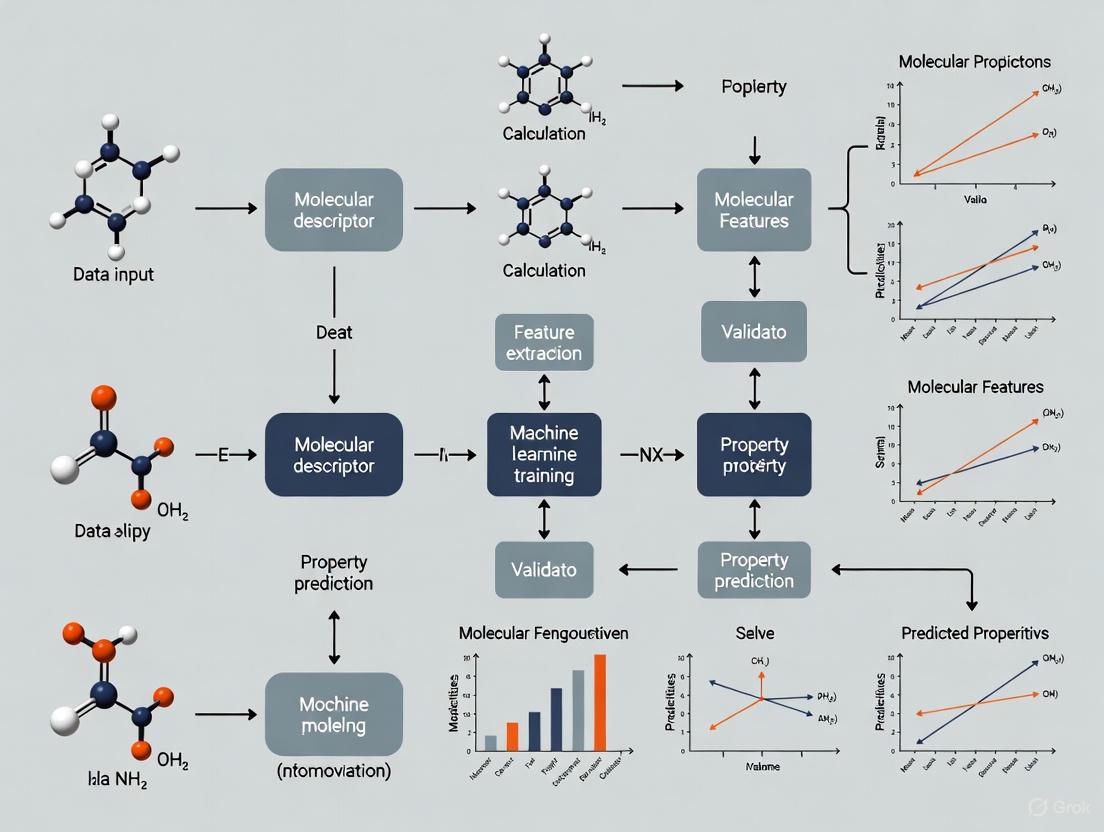

Visualization of Molecular Representation Workflows

Table 3: Key Software Tools and Databases for Molecular Representation

| Tool/Database | Type | Primary Function | Application Context |

|---|---|---|---|

| RDKit | Open-source Cheminformatics | Fingerprint generation, descriptor calculation, SMILES processing | General-purpose molecular representation and manipulation [4] |

| DeepMol | Python Package | Benchmarking different representations, drug sensitivity prediction | Comparative analysis of representation methods [2] |

| ChEMBL | Chemical Database | Bioactivity data, compound structures, target information | Source of validated structures and properties for model training [2] [5] |

| Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) | DFT Dataset | High-accuracy quantum chemistry calculations | Benchmarking representations against quantum chemical properties [6] |

| Meta's Universal Model for Atoms (UMA) | Foundation Model | Interatomic potential prediction | Transfer learning for molecular property prediction [6] |

| PubChem | Chemical Database | Compound information, bioactivity data, structural keys | Fingerprint generation and similarity searching [1] |

Traditional molecular representations—including fixed descriptors, molecular fingerprints, and SMILES strings—remain indispensable tools in computational chemistry and drug discovery research. Their computational efficiency, interpretability, and strong performance in low-data regimes continue to make them valuable for virtual screening, QSAR modeling, and molecular property prediction [2] [4]. While deep learning approaches show promise in data-rich environments, traditional representations provide robust baselines and often achieve competitive performance without extensive computational resources [4]. The development of methods to reconstruct molecular structures from fingerprints and the emergence of hybrid approaches that combine traditional and learned representations represent promising directions for future research [5] [3]. By understanding the strengths, limitations, and appropriate application contexts of each representation type, researchers can make informed decisions to advance their molecular property prediction projects.

Graph-based representations have fundamentally transformed computational modeling for molecular property prediction. By representing molecules as graphs, where atoms correspond to nodes and chemical bonds to edges, researchers can directly input molecular topology into machine learning models [7] [8]. This approach preserves the structural relationships that dictate chemical behavior and pharmacological activity.

Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) have emerged as the predominant architecture for learning from these representations. Through message-passing mechanisms, GNNs recursively aggregate information from neighboring atoms, building sophisticated representations that capture both local chemical environments and global molecular structure [9]. The field is currently advancing along multiple frontiers: novel GNN architectures with enhanced expressive power, integration with other model families like Transformers, and increasing emphasis on interpretability and data efficiency [7] [9] [8].

Current GNN Architectures for Molecular Property Prediction

Kolmogorov-Arnold Graph Neural Networks (KA-GNNs)

The recently proposed KA-GNN framework integrates Kolmogorov-Arnold networks (KANs) into GNN components to enhance expressivity and interpretability [7]. Unlike traditional multi-layer perceptrons that use fixed activation functions, KANs employ learnable univariate functions on edges, enabling more accurate and parameter-efficient function approximation.

KA-GNNs implement Fourier-series-based univariate functions within KAN layers, which theoretically enables capture of both low-frequency and high-frequency structural patterns in molecular graphs [7]. The framework systematically replaces conventional MLP-based transformations with Fourier-based KAN modules across three core GNN components: node embedding initialization, message passing, and graph-level readout. This creates a unified, fully differentiable architecture with enhanced representational power and improved training dynamics [7].

Two architectural variants have demonstrated particular promise: KA-Graph Convolutional Networks (KA-GCN) and KA-Graph Attention Networks (KA-GAT) [7]. In KA-GCN, each node's initial embedding is computed by passing concatenated atomic features and neighboring bond features through a KAN layer. Node features are then updated via residual KANs instead of traditional MLPs. KA-GAT incorporates edge embeddings by fusing bond features with endpoint node features using KAN layers, creating more expressive message-passing operations.

Table 1: Performance Comparison of GNN Architectures on Molecular Property Prediction Benchmarks

| Architecture | BBBP | Tox21 | ClinTox | BACE | SIDER | Average Improvement vs. Baseline |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| KA-GCN [7] | 0.741 | 0.783 | 0.943 | 0.858 | 0.635 | +4.2% |

| KA-GAT [7] | 0.749 | 0.791 | 0.951 | 0.866 | 0.641 | +4.8% |

| EHDGT [9] | 0.735 | 0.776 | 0.932 | 0.842 | 0.628 | +3.5% |

| ACES-GNN [8] | 0.728 | 0.769 | 0.925 | 0.831 | 0.619 | +2.8% |

| CRGNN [10] | 0.731 | 0.772 | 0.928 | 0.835 | 0.622 | +3.1% |

Performance metrics represent ROC-AUC scores. Baseline is standard GCN architecture.

Enhanced Graph Neural Networks and Transformers (EHDGT)

The EHDGT architecture addresses prevalent deficiencies in local feature learning and edge information utilization inherent in standard Graph Transformers [9]. This approach enhances both GNNs and Transformers through several innovations. For GNN components, EHDGT employs encoding strategies on subgraphs of the original graph, augmenting their proficiency for processing local information. For Transformer components, it incorporates edges into attention calculations and introduces a linear attention mechanism to reduce computational complexity [9].

A key innovation in EHDGT is the enhancement of positional encoding. The method superimposes edge-level positional encoding based on node-level random walk positional encoding, optimizing the utilization of structural information [9]. To balance local and global features, EHDGT implements a gate-based fusion mechanism that dynamically integrates outputs from both GNN and Transformer components, harnessing their synergistic capabilities.

Activity-Cliff-Explanation-Supervised GNN (ACES-GNN)

The ACES-GNN framework addresses the critical challenge of interpretability in molecular property prediction by integrating explanation supervision for activity cliffs (ACs) directly into GNN training [8]. Activity cliffs—pairs of structurally similar molecules with significant potency differences—pose particular challenges for traditional models due to their reliance on shared structural features.

ACES-GNN supervises both predictions and model explanations for ACs in the training set, enabling the model to identify patterns that are both predictive and chemically intuitive [8]. The framework assumes that attributions for minor substructure differences between an AC pair should reflect corresponding changes in molecular properties. This approach aligns model attributions with chemist-friendly interpretations, bridging the gap between prediction and explanation.

Consistency-Regularized Graph Neural Networks (CRGNN)

Data insufficiency remains a significant challenge in molecular property prediction due to the cost and time required for experimental property determination. CRGNN addresses this through a consistency regularization method based on augmentation anchoring [10]. This approach introduces a consistency regularization loss that quantifies the distance between strongly and weakly-augmented views of a molecular graph in the representation space.

By incorporating this loss into the supervised learning objective, the GNN learns representations where strongly-augmented views are mapped close to weakly-augmented views of the same graph [10]. This improves generalization while mitigating the negative effects of molecular graph augmentation, as even slight perturbations to molecular graphs can alter their intrinsic properties.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Implementing KA-GNN for Molecular Property Prediction

Purpose: To implement and evaluate Kolmogorov-Arnold Graph Neural Networks for molecular property prediction.

Materials and Reagents:

- Molecular datasets (e.g., MoleculeNet benchmarks)

- Python 3.8+

- PyTorch 1.12+ and PyTor Geometric 2.3+

- RDKit for molecular processing

- NVIDIA GPU with ≥8GB VRAM

Procedure:

- Data Preprocessing:

- Convert molecular SMILES strings to graph representations using RDKit

- Node features: atomic number, chirality, formal charge, hybridization, aromaticity, hydrogen count, radical electrons

- Edge features: bond type, conjugation, ring membership, stereochemistry

- Split data into training/validation/test sets (80/10/10) using scaffold splitting for realistic evaluation

Model Implementation:

- Implement Fourier-based KAN layer using sinusoidal basis functions with 10 harmonics

- Construct KA-GNN architecture:

- Node embedding: Pass concatenated atomic features through KAN layer

- Message passing: 5 layers with residual KAN connections

- Readout: Global attention pooling followed by KAN classification head

- Initialize parameters using Xavier uniform initialization

Training Configuration:

- Optimizer: AdamW with learning rate 0.001, weight decay 0.01

- Loss function: Cross-entropy for classification, MSE for regression

- Batch size: 32

- Early stopping with patience of 50 epochs

- Maximum training epochs: 500

Evaluation:

- Calculate ROC-AUC, precision-recall AUC, F1 score

- Perform statistical significance testing via bootstrapping

- Compare against GCN, GAT, and MPNN baselines

Diagram 1: KA-GNN Molecular Property Prediction Workflow

Protocol 2: Activity Cliff Explanation Supervision

Purpose: To implement explanation-guided learning for activity cliff prediction and interpretation.

Materials and Reagents:

- Activity cliff dataset with ground-truth explanations [8]

- PyTorch Geometric and Captum libraries

- Pre-trained GNN backbone (MPNN or GIN)

Procedure:

- Activity Cliff Identification:

- Calculate molecular similarity using Tanimoto coefficient on ECFP4 fingerprints

- Identify molecular pairs with structural similarity >0.9 and potency difference >10-fold

- Designate uncommon substructures as ground-truth explanations

Model Modification:

- Implement integrated gradients attribution method

- Add explanation supervision loss term:

- For AC pairs (mᵢ, mⱼ) with uncommon atomic sets Mᵢ and Mⱼ

- Ensure (Φ(ψ(Mᵢ)) - Φ(ψ(Mⱼ)))(yᵢ - yⱼ) > 0 [8]

- Combine prediction loss and explanation loss with weighting factor λ=0.7

Training:

- Freeze backbone layers for first 50 epochs

- Joint optimization of prediction and explanation losses for remaining epochs

- Monitor both prediction accuracy and explanation fidelity

Evaluation:

- Calculate explanation accuracy using ground-truth atom coloring

- Assess model robustness via perturbation tests

- Visualize explanatory substructures for chemist validation

Table 2: Research Reagent Solutions for GNN Molecular Property Prediction

| Reagent/Resource | Type | Function | Example Sources |

|---|---|---|---|

| MoleculeNet | Benchmark Dataset | Standardized evaluation across multiple molecular properties | [10] |

| OGB (Open Graph Benchmark) | Benchmark Dataset | Large-scale graph datasets for rigorous evaluation | - |

| RDKit | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular graph representation from SMILES | [8] |

| PyTorch Geometric | Deep Learning Library | GNN implementation and training | [7] [9] |

| CHEMBL | Chemical Database | Source of bioactive molecules with property data | [8] |

| Captum | Model Interpretation | Gradient-based attribution methods for explanations | [8] |

Results and Discussion

Performance Benchmarking

Recent architectural advances have demonstrated consistent improvements over conventional GNNs across multiple molecular property benchmarks. As shown in Table 1, KA-GNN variants achieve an average performance improvement of 4.2-4.8% compared to standard GCN baselines [7]. The integration of KAN modules provides particularly strong benefits for complex molecular properties where traditional activation functions may be suboptimal.

The EHDGT architecture shows competitive performance, especially on datasets requiring both local and global structural reasoning [9]. Its ability to capture long-range dependencies through Transformer components while maintaining local chemical sensitivity via GNNs makes it suitable for macromolecular properties and protein-ligand interactions.

ACES-GNN demonstrates that explanation supervision can simultaneously enhance both predictive accuracy and interpretability [8]. In evaluations across 30 pharmacological targets, 28 datasets showed improved explainability scores, with 18 achieving improvements in both explainability and predictivity. This suggests a positive correlation between improved prediction of activity cliff molecules and explanation quality.

Data Efficiency and Regularization

CRGNN and other consistency-regularized approaches address the critical challenge of data scarcity in molecular property prediction [10]. By leveraging molecular graph augmentation with consistency regularization, these methods improve generalization performance, particularly with limited labeled data. The augmentation anchoring strategy ensures that the model learns representations robust to semantically-irrelevant structural variations while remaining sensitive to chemically meaningful modifications.

Diagram 2: Consistency Regularization with Augmentation Anchoring

Graph-based representations coupled with advanced GNN architectures have established a powerful paradigm for molecular property prediction in drug discovery. The integration of novel mathematical frameworks like Kolmogorov-Arnold networks, hybrid GNN-Transformer architectures, and explanation-guided learning represents significant advances toward more accurate, data-efficient, and interpretable models.

These computational approaches enable researchers to capture complex structure-property relationships that directly inform molecular design and optimization. As the field progresses, the integration of three-dimensional molecular geometry, multi-scale representations encompassing both atomic and supra-molecular structure, and knowledge transfer across related targets will further enhance the predictive power and practical utility of GNNs in drug discovery pipelines.

The protocols and architectures presented herein provide researchers with practical frameworks for implementing state-of-the-art graph-based molecular property prediction, establishing a foundation for continued innovation at the intersection of geometric deep learning and computational chemistry.

The application of artificial intelligence in molecular property prediction is transforming the discovery of drugs, materials, and catalysts. Foundation models, pre-trained on extensive molecular datasets, have emerged as a powerful paradigm, enabling researchers to overcome the critical challenge of data scarcity that often impedes traditional machine learning approaches. These models leverage transfer learning to adapt knowledge from large-scale pre-training to specific downstream tasks with limited labeled data. This Application Note examines current pre-training strategies and transfer learning protocols for molecular foundation models, providing structured quantitative comparisons, detailed experimental methodologies, and practical toolkits for research implementation. Framed within the broader context of computational modeling for molecular property prediction, this resource equips scientists with the protocols needed to effectively implement these advanced techniques in their research workflows, ultimately accelerating molecular design and optimization.

Pre-training Strategies for Molecular Foundation Models

Molecular foundation models employ diverse pre-training strategies on large-scale datasets to learn generalized chemical representations before being adapted to specific property prediction tasks. The core principle involves self-supervised learning on unlabeled molecular datasets, typically represented as Simplified Molecular-Input Line-Entry System (SMILES) strings or molecular graphs, to capture fundamental chemical principles and structural patterns.

Architectural Approaches: Two prominent architectural paradigms have emerged: encoder-decoder transformers and graph neural networks. The SMI-TED model family exemplifies the transformer approach, utilizing an encoder-decoder mechanism trained on 91 million carefully curated molecules from PubChem [11] [12]. These models employ a novel pooling function that enables effective SMILES reconstruction while preserving molecular properties. For molecular crystals, the Molecular Crystal Representation from Transformers (MCRT) implements a multi-modal architecture that processes both atom-based graph embeddings and persistence image embeddings to capture local and global structural information [13].

Pre-training Tasks: Diverse pre-training objectives help models learn comprehensive representations. Common tasks include masked language modeling (MLM) where portions of SMILES strings are hidden and predicted, next sentence prediction adapted for molecular sequences, and molecular reconstruction objectives [13] [12]. For geometric deep learning, models like MCRT employ multiple pre-training tasks including graph-level and geometry-level objectives that enforce consistency between different molecular representations [13].

Table 1: Representative Molecular Foundation Models and Their Pre-training Specifications

| Model Name | Architecture | Pre-training Data Scale | Parameters | Key Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SMI-TED289M | Encoder-Decoder Transformer | 91 million molecules from PubChem | 289M (base), 8×289M (MoE) | Novel pooling function for SMILES reconstruction [11] |

| MCRT | Multi-modal Transformer | 706,126 experimental crystal structures from CSD | Not specified | Integrates atom-based graph embeddings + persistence images [13] |

| MoE-OSMI | Mixture-of-Experts | 91 million molecules from PubChem | 8×289M | Activates specialized sub-models for different tasks [11] |

Transfer Learning Protocols and Methodologies

Transfer learning enables the adaptation of pre-trained foundation models to specific molecular property prediction tasks through fine-tuning strategies that mitigate negative transfer—where performance degrades due to insufficient similarity between source and target tasks.

Quantifying Transferability

The Principal Gradient-based Measurement (PGM) provides a computation-efficient method to quantify transferability between source and target molecular properties prior to fine-tuning [14]. PGM calculates a principal gradient through a restart scheme that approximates the direction of model optimization on a dataset, then measures transferability as the distance between principal gradients obtained from source and target datasets.

Protocol: Principal Gradient-based Measurement (PGM)

- Model Initialization: Initialize the model with predetermined weights

- Principal Gradient Calculation:

- For each dataset (source and target), compute gradients on a subset of data

- Apply restart scheme with multiple re-initializations

- Calculate gradient expectations to obtain principal gradients

- Transferability Quantification:

- Compute distance between source and target principal gradients

- Smaller distances indicate higher transferability and reduced negative transfer risk

Fine-tuning Strategies

Conventional Fine-tuning: This approach involves initializing models with pre-trained weights followed by full or partial retraining on target task data. For SMI-TED models, this typically yields state-of-the-art performance across diverse molecular benchmarks [11].

Adaptive Checkpointing with Specialization (ACS): Designed for multi-task learning scenarios, ACS integrates shared task-agnostic backbones with task-specific heads, adaptively checkpointing model parameters when negative transfer signals are detected [15]. The protocol includes:

- Shared Backbone Training: Train a single graph neural network backbone across multiple tasks

- Task-Specific Heads: Employ dedicated multi-layer perceptron heads for each property prediction task

- Validation Monitoring: Track validation loss for each task during training

- Adaptive Checkpointing: Save the best backbone-head pair when a task's validation loss reaches a new minimum

Table 2: Performance Comparison of Transfer Learning Strategies on MoleculeNet Benchmarks

| Method | Strategy | Average Performance Gain | Key Advantages | Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGM-Guided Transfer [14] | Transferability quantification before fine-tuning | Strong correlation with actual performance | Prevents negative transfer; Computation-efficient | Requires principal gradient calculation |

| ACS [15] | Multi-task learning with adaptive checkpointing | 11.5% average improvement vs. baseline | Mitigates negative transfer; Effective with ultra-low data (≤29 samples) | Complex implementation; Requires validation monitoring |

| Conventional Fine-tuning [11] | Full fine-tuning of pre-trained models | Matches or exceeds SOTA on 9/11 benchmarks | Simple implementation; High performance on balanced data | Risk of negative transfer; Requires substantial target data |

Experimental Validation and Benchmarking

Rigorous evaluation on standardized benchmarks demonstrates the effectiveness of foundation models and transfer learning protocols for molecular property prediction.

Benchmarking Protocols

Dataset Selection and Splitting: The MoleculeNet benchmark provides standardized datasets for evaluating molecular property prediction, including quantum mechanical (QM7, QM8, QM9), physical chemistry (ESOL, FreeSolv, Lipophilicity), and biophysical (ClinTox, SIDER, Tox21) properties [11] [15]. Consistent with established practices, use the same train/validation/test splits as the original benchmarks to ensure unbiased evaluation [11]. For temporal validation in real-world scenarios, implement time-based splits where training data precedes test data chronologically [15].

Evaluation Metrics: For classification tasks (e.g., toxicity prediction), employ area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (ROC-AUC) and average precision (PR-AUC) [15]. For regression tasks (e.g., quantum property prediction), use root mean square error (RMSE) and mean absolute error (MAE) [11].

Performance Outcomes

Foundation Model Capabilities: The SMI-TED289M model demonstrates state-of-the-art performance, outperforming existing approaches on 9 of 11 MoleculeNet benchmarks [11]. On classification tasks, fine-tuned SMI-TED289M achieves superior performance in 4 of 6 datasets, while on regression tasks, it outperforms competitors across all 5 evaluated datasets [11].

Transfer Learning Efficacy: PGM-guided transfer learning shows strong correlation between measured transferability and actual performance improvements, effectively preventing negative transfer by selecting optimal source datasets [14]. The ACS method achieves accurate predictions with as few as 29 labeled samples in sustainable aviation fuel property prediction, demonstrating particular strength in ultra-low data regimes [15].

Table 3: Essential Research Reagents and Computational Resources for Molecular Foundation Models

| Resource Name | Type | Description | Access Information |

|---|---|---|---|

| PubChem [11] | Molecular Database | Curated repository of 91+ million chemical structures with associated properties | https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov |

| Cambridge Structural Database (CSD) [13] | Crystal Structure Database | 706,126+ experimentally determined organic and metal-organic crystal structures | https://www.ccdc.cam.ac.uk |

| MoleculeNet [14] [15] | Benchmark Suite | Standardized molecular property prediction datasets with predefined splits | https://moleculenet.org |

| MOSES [11] | Benchmarking Dataset | 1.9+ million molecular structures for evaluating generative models and reconstruction | https://github.com/molecularsets/moses |

| SMI-TED289M [11] [12] | Foundation Model | Encoder-decoder transformer pre-trained on 91M PubChem molecules | Hugging Face: ibm/materials.smi-ted |

| PGM [14] | Transferability Metric | Principal gradient-based measurement for quantifying task relatedness | Implementation details in original publication |

Workflow Visualization

Diagram 1: Molecular Foundation Model Workflow. This workflow encompasses data collection, pre-training strategies, transfer learning protocols, and evaluation phases for molecular property prediction.

Foundation models represent a transformative approach to molecular property prediction, effectively addressing data scarcity challenges through sophisticated pre-training strategies and targeted transfer learning methodologies. The protocols and analyses presented in this Application Note demonstrate that approaches such as PGM-guided transfer learning and adaptive checkpointing with specialization significantly enhance model performance while mitigating negative transfer risks. As these methodologies continue to evolve, they promise to further accelerate discoveries across drug development, materials science, and catalyst design by enabling more accurate predictions with increasingly limited experimental data.

Within the paradigm of computational modeling for molecular property prediction, the quality and composition of underlying datasets are not merely preliminary concerns but are foundational to the validity and practical utility of the resulting models. Data heterogeneity and distributional misalignments pose critical challenges for machine learning models, often compromising predictive accuracy and generalizability [16]. These issues are acutely present in critical early-stage drug discovery processes, such as preclinical safety modeling, where limited data and experimental constraints exacerbate integration problems [16]. This application note examines two intertwined pillars of dataset quality—comprehensive chemical space coverage and the critical awareness of benchmark dataset limitations—and provides structured protocols to empower researchers to systematically address these challenges in their molecular property prediction workflows.

The Challenge of Data Heterogeneity and Distributional Misalignment

Systematic analyses of public absorption, distribution, metabolism, and excretion (ADME) datasets have uncovered significant misalignments and inconsistent property annotations between gold-standard sources and popular benchmarks like the Therapeutic Data Commons (TDC) [16]. These discrepancies, which can originate from differences in experimental conditions, measurement protocols, or inherent chemical space coverage, introduce noise that ultimately degrades model performance. A critical finding is that naive data integration or standardization, despite harmonizing discrepancies and increasing training set size, does not automatically lead to improved predictive performance [16]. This underscores the necessity of rigorous data consistency assessment prior to model development.

Table 1: Common Sources of Dataset Discrepancies in Molecular Property Prediction

| Source of Discrepancy | Impact on Model Performance | Common Affected Properties |

|---|---|---|

| Experimental protocol variability (e.g., in vitro conditions) | Introduces batch effects and noise, reducing model accuracy and reliability [16] | ADME properties, solubility, toxicity [16] [17] |

| Chemical space coverage differences | Creates applicability domain gaps; models fail on underrepresented regions [16] | All properties, particularly for novel scaffolds [4] |

| Annotation inconsistencies between sources | Confuses model learning, leading to incorrect predictions for shared molecules [16] | Toxicity endpoints, clinical trial outcomes [16] [15] |

| Temporal and spatial data disparities | Inflates performance estimates in random splits versus time-split evaluations [15] | Properties measured over long periods or across labs [15] |

Chemical Space Coverage and Its Implications

Chemical space coverage refers to the breadth and diversity of molecular structures represented within a dataset. A dataset with limited coverage creates models with narrow applicability domains that fail to generalize to novel molecular scaffolds. The core challenge is that real-world chemical space is vast and high-dimensional, while experimental data is inherently sparse and costly to generate.

The Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) dataset represents a transformative effort to address the coverage challenge for quantum chemical properties, containing over 100 million density functional theory (DFT) calculations covering 83 elements and systems of up to 350 atoms [18] [19]. However, for experimental biological properties (e.g., ADME, toxicity), such exhaustive coverage remains impractical. In these domains, careful dataset curation and integration from multiple sources are necessary to expand coverage.

The impact of coverage is not theoretical. Models trained on datasets with expanded chemical space have demonstrated improved predictive accuracy and generalization. For instance, integrating aqueous solubility data from multiple curated sources nearly doubled molecular coverage, which resulted in better model performance [16]. Similarly, integrating proprietary datasets from Genentech and Roche into a multitask model improved predictive accuracy, an outcome attributed to the expanded chemical space that broadened the model's applicability domain [16].

Figure 1: A workflow for building datasets with robust chemical space coverage, emphasizing multi-source data collection and systematic gap analysis.

Limitations of Existing Benchmark Datasets

Heavy reliance on standardized benchmark datasets, while convenient for model comparison, introduces several often-overlooked risks that can compromise real-world applicability.

A primary concern is the limited practical relevance of some benchmark datasets. Studies indicate that achieving state-of-the-art performance on these benchmarks does not necessarily translate to meeting practical needs in real-world drug discovery [4]. Furthermore, the inconsistency in data splitting practices across literature introduces unfair performance comparisons. Without standardized, rigorous splitting protocols (e.g., scaffold-based splits that better simulate real-world generalization), reported performance improvements may represent statistical noise rather than genuine methodological advances [4].

Perhaps most critically, dataset provenance and quality are frequently overlooked. Significant distributional misalignments and annotation inconsistencies exist between commonly used benchmark sources and gold-standard datasets [16]. Naively aggregating data without addressing these fundamental inconsistencies can degrade, rather than improve, model performance.

Table 2: Popular Benchmark Sources and Their Documented Limitations

| Benchmark/Source | Primary Use | Reported Limitations |

|---|---|---|

| MoleculeNet | General molecular property prediction benchmark | Contains datasets of limited relevance to real-world drug discovery; evaluation metrics may lack practical relevance [4]. |

| Therapeutic Data Commons (TDC) | Standardized benchmarks for therapeutics development | Shows significant misalignments with gold-standard sources for ADME properties like half-life [16]. |

| ChEMBL | Large-scale bioactivity database | Data extracted from diverse literature sources, leading to potential heterogeneity in experimental protocols and measurements. |

| Genentech/Roche (Proprietary) | ADME and physicochemical property modeling | Used as an example of high-quality data that can improve models when integrated, but access is restricted [16]. |

Experimental Protocols for Data Consistency Assessment

Protocol: Data Curation and Standardization

Purpose: To create a clean, standardized, and non-redundant dataset from raw molecular data sources, minimizing "internal" noise before integration or modeling.

Structure Standardization:

- Input: Raw SMILES, CAS numbers, or chemical names.

- Procedure: Use the RDKit Python package to standardize structures. This includes neutralizing salts, removing duplicates at the SMILES level, and generating canonical SMILES [17].

- Exclusion Criteria: Filter out inorganic compounds, organometallics, mixtures, and molecules containing unusual elements (beyond H, C, N, O, F, Br, I, Cl, P, S, Si) [17].

Property Value Curation:

- For Continuous Data: Identify duplicates. If the standardized standard deviation (standard deviation/mean) for a duplicate's values is > 0.2, remove the data point as ambiguous. Otherwise, average the values [17].

- For Classification Data: Remove compounds that do not have the same response value across duplicate entries [17].

- Outlier Removal: Calculate the Z-score for each data point within a dataset. Remove data points with a Z-score > 3 as potential "intra-outliers" resulting from annotation errors [17].

Protocol: Multi-Source Data Integration with AssayInspector

Purpose: To systematically identify and address distributional misalignments and annotation conflicts when integrating molecular property data from multiple public or proprietary sources.

Tool Setup:

- Install the AssayInspector package (publicly available at https://github.com/chemotargets/assay_inspector) [16].

- Prepare input files: Each dataset should be a CSV file containing canonical SMILES and the target property/endpoint.

Descriptive Analysis and Statistical Testing:

- Run AssayInspector to generate a summary report for each data source, including the number of molecules, endpoint statistics (mean, SD, min, max, quartiles), and class counts [16].

- Perform statistical comparisons. For regression tasks, AssayInspector applies the two-sample Kolmogorov–Smirnov (KS) test to compare endpoint distributions between dataset pairs. For classification, it uses the Chi-square test [16].

Visualization and Discrepancy Detection:

- Generate property distribution plots to visually identify significantly different distributions between sources [16].

- Execute dataset intersection analysis to identify shared compounds and quantify the numerical differences in their annotations across datasets. This highlights conflicting labels for the same molecule [16].

- Perform chemical space visualization using the built-in UMAP projection of molecular fingerprints (e.g., ECFP4) to assess dataset coverage and overlap [16].

Insight Report Generation:

- Review the automatically generated insight report from AssayInspector, which provides alerts on dissimilar datasets, datasets with conflicting annotations, divergent datasets with low molecular overlap, and redundant datasets [16].

- Use these insights to make informed data integration decisions, such as excluding datasets with irreconcilable differences or applying robust normalization techniques.

Figure 2: A protocol for assessing data consistency across multiple molecular datasets, leveraging the AssayInspector tool for statistical and visual analysis.

Table 3: Key Software Tools for Data Handling and Model Evaluation

| Tool Name | Type | Primary Function | Application Note |

|---|---|---|---|

| AssayInspector [16] | Python Package | Data consistency assessment prior to modeling. | Critical for identifying outliers, batch effects, and distributional discrepancies when integrating datasets. Model-agnostic. |

| RDKit [4] [17] | Cheminformatics Library | Molecular standardization, descriptor calculation, and fingerprint generation. | The workhorse for structure curation and feature generation. Used internally by many other tools. |

| OPER | QSAR Model Suite | Predicts physicochemical and toxicokinetic properties. | Identified in benchmarking as a robust tool with good predictivity, especially for PC properties [17]. |

| Open Molecules 2025 (OMol25) [18] [19] | Quantum Chemical Dataset | Provides DFT-level data for training machine learning interatomic potentials. | Unprecedented in scale and diversity for quantum property prediction. Use for pre-training or developing MLIPs. |

| Therapeutic Data Commons (TDC) [16] [4] | Benchmark Platform | Provides standardized datasets for therapeutic development. | Useful for initial benchmarking but be aware of documented misalignments with gold-standard data [16]. |

The Role of High-Throughput Computing in Generating Training Data

High-throughput computing (HTC) has emerged as a transformative paradigm for generating the large-scale, high-quality training data required for advanced computational models in molecular property prediction. By automating and parallelizing thousands of first-principles calculations and experimental data processes, HTC addresses the critical data scarcity and quality issues that have historically constrained machine learning (ML) applications in drug discovery and materials science [20] [21]. This protocol details the implementation of HTC-driven workflows for data generation, establishing robust benchmarks for model training and enabling the discovery of novel materials and drug candidates with targeted properties.

The accuracy of predictive models in molecular property prediction is fundamentally limited by the availability of high-quality, consistently generated experimental and computational data [21]. Traditional experimental approaches are often resource-intensive and time-consuming, while data curated from disparate literature sources frequently suffer from inconsistencies due to varying experimental conditions and methodologies [20] [21]. A recent analysis comparing IC50 values reported by different groups for the same compounds found almost no correlation between the reported values, highlighting the severe quality issues with many existing public datasets [21].

High-throughput computing directly addresses this bottleneck by enabling the systematic generation of standardized data at scale. The integration of HTC with data-driven methodologies has optimized performance predictions, making it possible to identify novel materials with desirable properties efficiently [20]. This shift towards digitized material design reduces reliance on trial-and-error experimentation and promotes data-driven innovation, particularly in critical areas such as absorption, distribution, metabolism, excretion, and toxicity (ADMET) prediction [21].

High-Throughput Computational-Experimental Screening Protocols

The most effective HTC frameworks combine computational and experimental methods in an integrated, closed-loop discovery process [22] [23]. These protocols leverage computational screening to guide experimental validation, which in turn refines the computational models.

Protocol for Bimetallic Catalyst Discovery

A representative HTC screening protocol for discovering bimetallic catalysts with properties comparable to palladium (Pd) involves the following automated workflow [23]:

- Candidate Generation: Define a search space of 435 binary systems from 30 transition metals, considering 10 ordered crystal phases for each combination, resulting in 4,350 initial candidate structures.

- Thermodynamic Stability Screening: Use density functional theory (DFT) calculations to compute formation energy (∆Ef) for each structure. Filter candidates with ∆Ef < 0.1 eV to ensure thermodynamic stability and synthetic feasibility.

- Electronic Structure Similarity Analysis: For thermodynamically stable candidates, calculate the electronic density of states (DOS) pattern projected on close-packed surfaces. Quantify similarity to the reference Pd(111) surface using the ΔDOS metric:

ΔDOS₂₋₁ = {∫ [DOS₂(E) - DOS₁(E)]² g(E;σ) dE}^(1/2)whereg(E;σ)is a Gaussian distribution function centered at the Fermi energy with σ = 7 eV. - Experimental Validation: Synthesize and test top candidates (those with lowest ΔDOS values) for target catalytic reactions (e.g., H₂O₂ synthesis). Compare performance metrics (e.g., catalytic activity, cost-normalized productivity) against reference Pd catalyst.

Table 1: Performance Metrics of HTC-Discovered Bimetallic Catalysts for H₂O₂ Synthesis

| Catalyst Composition | DOS Similarity to Pd (ΔDOS) | Catalytic Performance vs. Pd | Cost-Normalized Productivity vs. Pd |

|---|---|---|---|

| Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ | Low | Comparable | 9.5x enhancement |

| Au₅₁Pd₄₉ | Low | Comparable | Not specified |

| Pt₅₂Pd₄₈ | Low | Comparable | Not specified |

| Pd₅₂Ni₄₈ | Low | Comparable | Not specified |

This protocol successfully identified several high-performing catalysts, including the previously unreported Ni₆₁Pt₃₉ which outperformed the benchmark Pd catalyst with a 9.5-fold enhancement in cost-normalized productivity [23].

Workflow Architecture for HTC Data Generation

The following diagram illustrates the automated, multi-stage workflow for high-throughput data generation, integrating both computational and experimental components:

HTC Data Generation Workflow

Computational Methods and Data Generation Standards

High-throughput computational screening relies on robust first-principles calculations, primarily Density Functional Theory (DFT), to predict molecular and material properties reliably. Standardized protocols are essential for balancing precision and computational efficiency across large-scale simulations [24].

Standard Solid-State Protocols (SSSP) for High-Throughput DFT

The Standard Solid-State Protocols provide optimized parameters for high-throughput DFT calculations, ensuring consistent data quality across diverse material systems [24]:

- Pseudopotential Selection: Curated libraries of extensively tested pseudopotentials suitable for different precision/efficiency tradeoffs.

- k-point Sampling Optimization: Automated determination of Brillouin zone sampling density based on material system and desired precision.

- Smearing Techniques: Application of smearing methods (e.g., Marzari-Vanderbilt cold smearing) to improve convergence in metallic systems, with optimized temperatures for different material classes.

Table 2: Standardized Protocols for High-Throughput DFT Calculations

| Protocol Parameter | High-Precision Setting | High-Efficiency Setting | Target Error/Property |

|---|---|---|---|

| Plane-Wave Cutoff Energy | Based on pseudopotential recommendations (SSSP precision) | 20-30% reduction from precision setting | Total energy convergence (< 1 meV/atom) |

| k-point Sampling Density | Γ-centered grid with spacing < 0.02 Å⁻¹ | Γ-centered grid with spacing < 0.04 Å⁻¹ | Fermi surface integration accuracy |

| Smearing Method | Marzari-Vanderbilt cold smearing | Fermi-Dirac smearing | Metallic system convergence |

| Electronic SCF Convergence | 10⁻⁸ Ha/atom | 10⁻⁶ Ha/atom | Total energy and forces |

| Force Convergence | < 0.001 eV/Å | < 0.01 eV/Å | Ionic relaxation accuracy |

These protocols operate within computational workflow engines (e.g., AiiDA, FireWorks) acting as an interface between high-level workflow logic and the inner-level parameters of DFT codes such as Quantum ESPRESSO [24].

Machine Learning Integration and Training Data Applications

The data generated through HTC pipelines enables the training of sophisticated machine learning models for molecular property prediction. The SCAGE (self-conformation-aware graph transformer) architecture demonstrates how HTC-generated data can be leveraged in pretraining frameworks [25].

SCAGE Multitask Pretraining Framework

The SCAGE model utilizes a multitask pretraining paradigm (M4) incorporating four supervised and unsupervised tasks on approximately 5 million drug-like compounds [25]:

- Molecular Fingerprint Prediction: Learning compressed representations of molecular structures.

- Functional Group Prediction: Incorporating chemical prior information through a novel annotation algorithm that assigns unique functional groups to each atom.

- 2D Atomic Distance Prediction: Capturing basic molecular topology.

- 3D Bond Angle Prediction: Learning spatial conformation information through a Multiscale Conformational Learning (MCL) module.

This multitask approach, balanced using a Dynamic Adaptive Multitask Learning strategy, enables the model to learn comprehensive semantics from molecular structures to functions, significantly improving generalization across various molecular property tasks [25].

Table 3: Performance Comparison of SCAGE vs. State-of-the-Art Models on Molecular Property Prediction

| Model Architecture | Pretraining Data Scale | Average Accuracy Gain | Key Advantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| SCAGE (Proposed) | ~5 million compounds | Significant improvement | Conformation-aware, functional group interpretation |

| Uni-Mol | Large-scale 3D data | Baseline | 3D structural understanding |

| GROVER | 10 million molecules | Moderate improvement | Self-supervised graph learning |

| ImageMol | 10 million molecular images | Moderate improvement | Multi-granularity learning |

| KANO | Knowledge-graph enhanced | Moderate improvement | Functional group incorporation |

Data Generation for Blind Challenges and Model Validation

High-quality HTC-generated data enables rigorous model validation through blind challenges, which are critical for assessing real-world performance [21]. The OpenADMET initiative, for example, combines high-throughput experimentation and computation to generate consistent datasets for regular blind challenges focused on ADMET endpoints, mimicking the successful CASP challenges in protein structure prediction [21].

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagent Solutions

The following table catalogs key computational tools and resources essential for implementing HTC-driven data generation for molecular property prediction:

Table 4: Essential Research Reagent Solutions for HTC Data Generation

| Tool/Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Application in HTC Workflow |

|---|---|---|---|

| AiiDA | Workflow Manager | Automates and manages computational workflows, ensuring reproducibility | Coordinates high-throughput DFT calculations across computing resources [24] |

| Quantum ESPRESSO | DFT Code | Performs first-principles electronic structure calculations | Core engine for property prediction in materials screening [24] |

| SSSP Pseudopotentials | Computational Library | Curated collection of optimized pseudopotentials | Ensures accuracy and efficiency in high-throughput DFT simulations [24] |

| OpenADMET Datasets | Experimental Database | High-quality, consistent ADMET property measurements | Provides ground-truth data for model training and validation [21] |

| SCAGE Framework | ML Architecture | Pretrained model for molecular property prediction | Leverages HTC-generated conformational data for enhanced prediction [25] |

| Materials Project API | Materials Database | Access to computed properties of thousands of inorganic compounds | Reference data for validation and candidate generation [20] |

High-throughput computing serves as the foundational engine for generating the standardized, large-scale training data required to advance molecular property prediction. Through integrated computational-experimental protocols, standardized DFT methodologies, and specialized ML architectures, HTC enables researchers to overcome historical data bottlenecks and accelerate the discovery of novel materials and therapeutic compounds. The continued development of open data initiatives and robust computational workflows will further enhance the role of HTC in powering the next generation of predictive models in molecular science.

Advanced Architectures and Implementation Strategies for Real-World Applications

Molecular property prediction is a critical task in cheminformatics and drug discovery, enabling researchers to rapidly screen compounds and prioritize candidates for synthesis and testing. Traditional machine learning approaches have relied on expert-crafted molecular descriptors or fingerprints, which require significant domain knowledge to engineer and may not fully capture complex molecular characteristics [26]. The emergence of foundation models represents a paradigm shift in this field. These models are pre-trained on vast amounts of unlabeled data to learn general molecular representations, which can then be fine-tuned for specific prediction tasks with limited labeled examples, addressing the data scarcity common in chemical domains [27].

This application note explores CheMeleon, a novel descriptor-based foundation model that leverages Directed Message-Passing Neural Networks (D-MPNNs) for molecular property prediction. We examine its architecture, performance benchmarks, and provide detailed protocols for implementation, framed within the broader context of computational modeling for molecular property prediction research.

Technical Foundation

Directed Message-Passing Neural Networks (D-MPNNs)

Message Passing Neural Networks (MPNNs) provide a framework for learning from graph-structured data by iteratively passing information between connected nodes. In the context of molecular graphs, atoms represent nodes and bonds represent edges. The Directed MPNN (D-MPNN) variant introduces a crucial architectural improvement over generic MPNNs by associating messages with directed edges (bonds) rather than vertices (atoms) [26].

This directed approach prevents "message totters" – unnecessary loops where messages pass back to their originator atoms along paths of the form v1→v2→v1. By eliminating this redundancy, D-MPNNs create more efficient and effective message passing trajectories. In practice, a message from atom 1 to atom 2 propagates only to atoms 3 and 4 in the next iteration, rather than circling back to atom 1 [26]. This architecture more closely mirrors belief propagation in probabilistic graphical models and has demonstrated superior performance in molecular property prediction tasks across both public and proprietary datasets [26].

Descriptor-Based Foundation Models

Foundation models in chemistry address data scarcity through self-supervised pre-training on large molecular databases before fine-tuning on specific property prediction tasks. CheMeleon innovates within this space by using deterministic molecular descriptors from the Mordred package as pre-training targets [28]. Unlike conventional approaches that rely on noisy experimental data or computationally expensive quantum mechanical simulations, CheMeleon learns to predict 1,613 molecular descriptors from the ChEMBL database in a noise-free setting, compressing them into a dense latent representation of only 64 features [27]. This approach allows the model to learn rich molecular representations that effectively capture structural nuances and separate distinct chemical series [28].

CheMeleon Architecture and Implementation

Model Architecture

CheMeleon employs a dual-phase architecture consisting of pre-training and fine-tuning stages:

Pre-training Phase: The model is trained as a self-supervised autoencoder using a D-MPNN backbone to predict 1,613 molecular descriptors from the Mordred package calculated for molecules in the ChEMBL database. The model learns to compress these descriptors into a dense latent representation of 64 features [27].

Fine-tuning Phase: The pre-trained model is adapted to specific property prediction tasks through transfer learning, requiring minimal task-specific data – in some cases, fewer than 100 training examples [29].

The following diagram illustrates the complete CheMeleon workflow, from input processing through to final property prediction:

Research Reagent Solutions

Table 1: Essential computational tools and resources for implementing CheMeleon

| Resource Name | Type | Primary Function | Implementation Role |

|---|---|---|---|

| Mordred Descriptors | Molecular Descriptor Package | Calculates 1,613 molecular descriptors | Pre-training targets for foundational representation learning [28] |

| ChEMBL Database | Chemical Database | Provides ~1.6M bioactive molecules | Large-scale pre-training dataset [27] |

| D-MPNN Architecture | Neural Network Framework | Directed message passing between molecular graph nodes | Core encoder architecture for processing molecular structure [26] |

| ChemProp Library | Software Framework | D-MPNN implementation and model training | Primary codebase for fine-tuning and inference (v2.2.0+) [30] |

| Polaris Benchmark | Evaluation Suite | Standardized molecular property prediction tasks | Performance validation across 58 datasets [28] |

Performance Analysis

Benchmark Results

CheMeleon has been extensively evaluated against established baselines across multiple benchmark suites. The following table summarizes its performance compared to other approaches:

Table 2: Performance comparison of CheMeleon against baseline models on standardized benchmarks

| Model | Polaris Win Rate | MoleculeACE Win Rate | Data Efficiency | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CheMeleon | 79% | 97% | <100 examples, <10 minutes [29] | Struggles with activity cliffs [28] |

| Random Forest | 46% | 63% | Requires more data and features | Limited representation learning |

| fastprop | 39% | N/R | Moderate | Descriptor-based only |

| ChemProp | 36% | N/R | Moderate | Standard D-MPNN without pre-training |

| Other Foundation Models | Variable | Lower than CheMeleon [28] | Varies by model | Often require complex pre-training |

The exceptional performance of CheMeleon, particularly its 97% win rate on MoleculeACE assays, demonstrates its effectiveness across diverse molecular property prediction tasks. The model's data efficiency is particularly noteworthy, matching the performance of expert-crafted models with fewer than 100 training examples in under 10 minutes [29].

Representation Quality Analysis

Visualization of CheMeleon's learned representations using t-SNE projections demonstrates effective separation of chemical series, confirming the model's ability to capture structurally meaningful molecular representations [28]. This structural discrimination capability is crucial for real-world drug discovery applications where distinguishing between related compound series is essential.

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Pre-training CheMeleon

Objective: Train a foundational CheMeleon model using molecular descriptors from a large chemical database.

Workflow Steps:

Data Collection

- Obtain ~1.6 million bioactive molecules from ChEMBL database [27]

- Standardize molecular structures (tautomer normalization, charge correction)

- Remove duplicates and compounds with structural errors

Descriptor Calculation

- Compute 1,613 Mordred descriptors for each molecule using MordredCommunity package

- Handle missing values and normalize descriptor distributions

- Split data into training/validation sets (98%/2%)

Model Configuration

- Implement D-MPNN architecture with bond-focused message passing

- Set hidden size to 1,600 dimensions (compatible with descriptor count)

- Configure model to output 1,613 continuous values (descriptor predictions)

Training Parameters

- Batch size: 128-256 (adjust based on GPU memory)

- Learning rate: 0.001 with linear decay

- Loss function: Mean Squared Error (MSE) on normalized descriptors

- Early stopping based on validation loss plateau

Latent Representation Extraction

- Extract 64-dimensional latent vectors from bottleneck layer

- Save pre-trained weights for fine-tuning

The following diagram illustrates the pre-training workflow:

Protocol 2: Fine-tuning for Property Prediction

Objective: Adapt a pre-trained CheMeleon model to specific molecular property prediction tasks.

Workflow Steps:

Data Preparation

- Collect labeled dataset for target property (can be <100 samples)

- Apply same preprocessing as pre-training phase

- Perform scaffold split to ensure generalization [26]

Model Initialization

- Load pre-trained CheMeleon weights

- Replace output layer with task-specific head (regression/classification)

- Optionally freeze early layers for very small datasets

Fine-tuning Configuration

- Batch size: 16-32 (smaller than pre-training)

- Learning rate: 0.0001 (lower than pre-training)

- Task-appropriate loss function (MSE for regression, Cross-Entropy for classification)

- Monitor validation performance with early stopping

Evaluation

- Predict on held-out test set

- Calculate task-relevant metrics (RMSE, ROC-AUC, etc.)

- Compare against baseline models

- Analyze performance on activity cliffs if relevant

Protocol 3: Generating CheMeleon Fingerprints

Objective: Create CheMeleon molecular representations without fine-tuning.

Workflow Steps:

Environment Setup

- Install ChemProp 2.2.0 or newer:

pip install 'chemprop>=2.2.0' - Download

chemeleon_fingerprint.pyfrom official repository [30]

- Install ChemProp 2.2.0 or newer:

Implementation

- Import

CheMeleonFingerprintclass - Instantiate with pre-trained weights

- Process SMILES strings or RDKit mol objects

- Import

Usage

- Generate fingerprints for single molecules or batches

- Integrate representations into existing machine learning pipelines

- Use for similarity analysis or visualization

Applications in Drug Discovery

CheMeleon's combination of data efficiency and high performance makes it particularly valuable in drug discovery workflows:

- High-Throughput Screening Triage: Rapidly prioritize compounds from virtual screens with minimal labeled data

- Multi-Property Optimization: Simultaneously predict multiple ADMET properties early in discovery

- Transfer Learning: Leverage knowledge from abundant assay data to predict properties with limited data

- Lead Optimization: Guide structural modifications using interpretable representations that separate chemical series

The model's ability to match expert-crafted model performance with minimal training data represents a significant advancement for computational chemistry workflows, particularly in early-stage discovery where data is most limited [29].

Implementation Considerations

Computational Requirements

Successful implementation requires appropriate computational resources:

- Pre-training: Significant resources needed (days on multiple GPUs) but performed once

- Fine-tuning: Efficient (minutes to hours on single GPU, even CPU for small datasets)

- Inference: Near real-time prediction suitable for interactive design

Best Practices

- Data Quality: Ensure standardized molecular input (tautomer, charge, stereochemistry)

- Descriptor Preprocessing: Normalize Mordred descriptors during pre-training

- Transfer Learning Strategy: Adjust layer freezing based on dataset size

- Evaluation: Always use scaffold splits to assess real-world generalization [26]

CheMeleon represents a significant advancement in molecular property prediction through its innovative combination of descriptor-based pre-training and Directed Message-Passing Neural Networks. By achieving state-of-the-art performance while requiring minimal fine-tuning data, it addresses critical challenges in computational drug discovery. The protocols provided herein enable researchers to implement this powerful approach within their molecular design workflows, potentially accelerating the identification and optimization of novel therapeutic compounds.

The accurate prediction of molecular properties is a cornerstone in accelerating drug discovery and materials science. Traditional computational models often rely on a single type of molecular representation, which can limit their predictive power and generalizability. This application note details advanced multi-view and multi-modal frameworks that integrate diverse molecular representations—specifically SMILES (Simplified Molecular Input Line Entry System), SELFIES (SELF-referencing Embedded Strings), and molecular graphs. Framed within a broader thesis on computational modeling, these protocols demonstrate how leveraging the complementary strengths of these representations leads to enhanced robustness and accuracy in molecular property prediction tasks for research scientists and drug development professionals. By systematically combining these views, these frameworks mitigate the inherent limitations of any single representation, enabling more reliable virtual screening and property estimation.

Molecular Representations: A Primer

At the heart of any molecular machine-learning model is the initial representation of the chemical structure. The choice of representation fundamentally shapes how a model learns and generalizes.

- SMILES: A line notation that uses ASCII strings to describe the structure of a molecule using a depth-first traversal of its graph. While widely used and human-readable, its major limitations include syntactic fragility (small changes can generate invalid strings) and potential ambiguity in representing the same molecule [31] [32].

- SELFIES: A robust string-based representation developed to address the limitations of SMILES. A key innovation of SELFIES is its foundation in a formal grammar, which guarantees that every possible string is syntactically valid and corresponds to a viable molecule. This 100% robustness makes it particularly suitable for generative models and evolutionary algorithms [33] [32].

- Molecular Graphs: This representation explicitly models a molecule as a graph, where atoms are nodes and bonds are edges. This two-dimensional format naturally captures the topological structure of a molecule, making it the preferred representation for Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) [34]. Hierarchical graph structures can further decompose molecules into atom-, motif-, and graph-level features, providing a multi-scale perspective [34].

Table 1: Comparison of Fundamental Molecular Representations

| Representation | Format | Key Advantages | Key Limitations |

|---|---|---|---|

| SMILES | String | Human-readable, concise, extensive historical use in databases | Syntactically fragile; invalid outputs common in generation; ambiguous representations |

| SELFIES | String | 100% robust (all strings are valid); simpler grammar; avoids semantic errors | Relatively newer, with a smaller ecosystem of supporting tools |

| Molecular Graph | Graph (Nodes & Edges) | Naturally captures topology and connectivity; invariant to atom ordering | Does not inherently encode 3D spatial information; requires specialized GNN architectures |

Multi-View Fusion Frameworks and Protocols

Multi-view frameworks integrate different representations of the same underlying molecular entity, treating each representation as a distinct "view." The following protocols outline key implementations.

Protocol: The MoL-MoE (Multi-view Mixture-of-Experts) Framework

The MoL-MoE framework is designed to dynamically leverage the complementary strengths of SMILES, SELFIES, and graph representations [35].

1. Principle: The model employs a Mixture-of-Experts (MoE) architecture, where separate "expert" sub-networks are dedicated to processing each molecular representation. A gating network then learns to selectively weigh and combine the contributions of these experts based on the specific task or molecule.

2. Experimental Workflow:

- Input Preparation: Encode each molecule in the dataset concurrently into its SMILES, SELFIES, and molecular graph representations.

- Expert Model Training:

- Implement four expert neural networks for each of the three modalities (totaling 12 experts).

- For string-based representations (SMILES/SELFIES), experts are typically transformer-based encoders.

- For graph-based representations, experts are Graph Neural Networks (GNNs).

- Gating Network Training: A trainable gating network is implemented to calculate a set of weights for the experts. For a given input molecule, the gating network outputs a weight for each expert, and the final prediction is a weighted sum of all experts' outputs.

- Routing and Activation: The top-k experts (e.g., k=4 or k=6) are activated for each input, ensuring computational efficiency [35].

- Fusion and Prediction: The outputs from the activated experts are aggregated via the weighted sum from the gating network, and the fused representation is fed into a task-specific head (e.g., an MLP) for the final property prediction.