Advanced Troubleshooting Guide for Heterologous Expression Systems: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Solutions

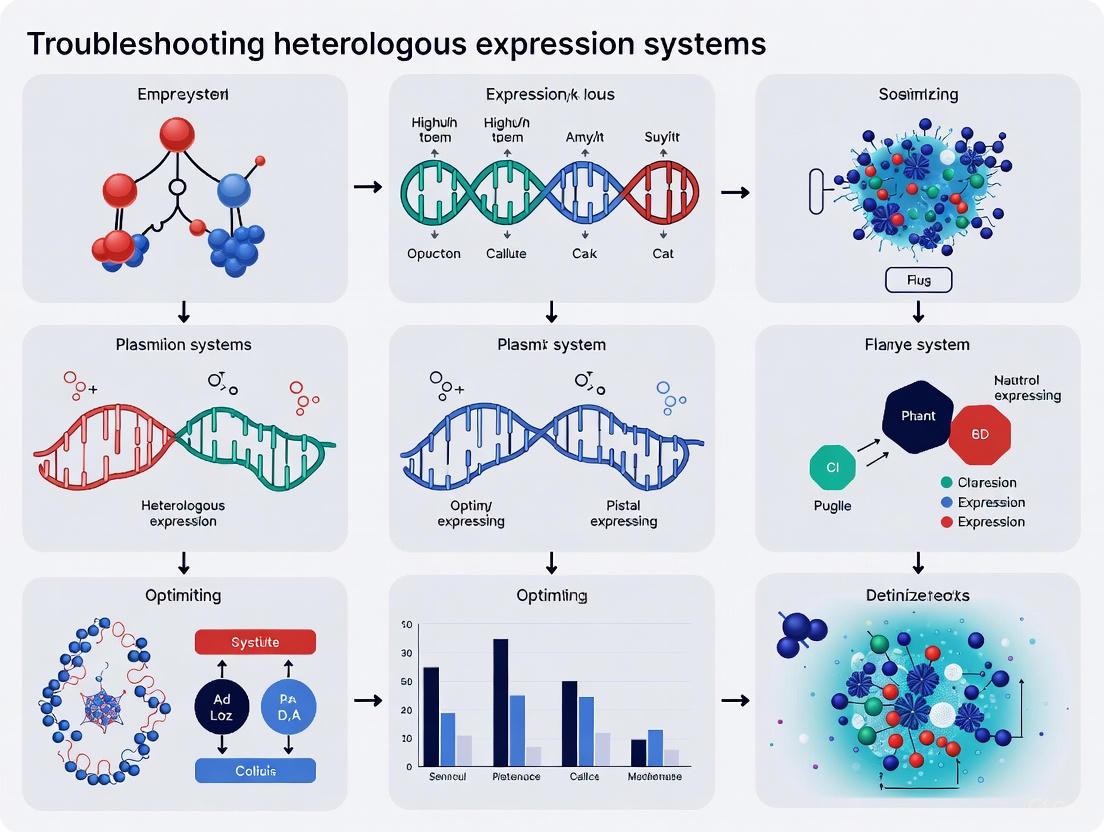

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenges researchers face in heterologous protein expression, a cornerstone technique in biotechnology and drug development.

Advanced Troubleshooting Guide for Heterologous Expression Systems: From Foundational Principles to Cutting-Edge Solutions

Abstract

This comprehensive guide addresses the critical challenges researchers face in heterologous protein expression, a cornerstone technique in biotechnology and drug development. Covering foundational principles to advanced optimization, it systematically explores host system selection (E. coli, yeast), vector design, and codon optimization strategies. The article provides practical methodologies for expressing complex proteins including membrane proteins and toxic proteins, alongside proven troubleshooting protocols for low yields, solubility issues, and proteolysis. Through comparative analysis of expression platforms and validation techniques, it equips scientists with integrated strategies to overcome expression barriers and maximize success in producing recombinant proteins for research and therapeutic applications.

Understanding Heterologous Expression: Core Principles and Common Roadblocks

Core Concepts and FAQs

What is heterologous expression?

Heterologous expression is the process of introducing and expressing a gene or DNA sequence from one species into a different host organism. This host organism, known as the heterologous host, then uses its own cellular machinery to produce the recombinant protein. The production of a protein encoded by recombinant DNA in a heterologous host is a cornerstone of modern biotechnology [1].

What are the main applications of heterologous expression?

This technology is fundamental to various scientific and industrial endeavors. It is used for the large-scale production of therapeutic proteins and enzymes, functional analysis of genes and proteins, structural biology studies requiring high protein yields, and the development of biopharmaceuticals, including some vaccines, as evidenced by its role in certain COVID-19 vaccine production [1].

How do I choose the right expression system?

Selecting an optimal expression system depends on multiple criteria, including the origin and intrinsic characteristics of your target protein, the required post-translational modifications, the intended application, and practical considerations like cost and laboratory expertise [2] [1]. The table below summarizes the common systems:

Table 1: Comparison of Heterologous Expression Systems

| Expression System | Typical Yield | Key Advantages | Key Limitations | Ideal For |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bacterial (e.g., E. coli) | High (mg to g/L) | Simple, fast, low-cost, high yield [2] | Lack of complex PTMs, protein misfolding & inclusion bodies [2] | Non-glycosylated proteins, prokaryotic proteins, research requiring high yield quickly [2] |

| Yeast (e.g., P. pastoris) | High | Eukaryotic PTMs, scalable, cost-effective [2] | Glycosylation patterns differ from mammals | Secreted proteins, scalable production of eukaryotic proteins [2] [3] |

| Insect Cells (Baculovirus) | Up to 500 mg/L [2] | Better PTMs than yeast, more native-like protein folding, handles large proteins | Culture can be challenging, slower than bacterial systems [2] | Complex eukaryotic proteins, membrane proteins, viral proteins |

| Mammalian Cells (e.g., HEK293, CHO) | Variable | Most native PTMs and protein folding, produces functional proteins [2] | High cost, slow growth, technically demanding [2] | Therapeutic proteins, complex proteins requiring authentic PTMs [2] |

| Cell-Free | Low to moderate | Rapid, bypasses cell viability, good for toxic proteins [2] [4] | Not sustainable for large-scale production [2] | High-throughput screening, labeling for structural studies, toxic proteins [4] |

Troubleshooting Common Experimental Issues

Problem 1: No or Low Protein Expression

This is a common issue where the target protein is not detected or is produced at very low levels after induction.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Verify Your Construct: The first step is always to check your plasmid by sequencing the entire expression cassette. A single point mutation or a frameshift can introduce a premature stop codon, preventing expression [5] [6].

- Check Promoter and Ribosome Binding Site (RBS): Secondary structures in the mRNA around the 5' untranslated region (UTR) or the beginning of the coding sequence can prevent efficient translation by the ribosome. Trying a different promoter or altering the RBS to more closely match the ideal sequence (e.g., AGGAGGT in E. coli) can help [5] [4].

- Assay Sensitivity: Do not rely solely on SDS-PAGE with Coomassie staining, as it is relatively insensitive. Use a more sensitive method like western blot (if you have an antibody) or an activity assay to confirm whether low-level expression is occurring [5].

- Codon Usage: Check if your gene of interest is rich in codons that are rare for your expression host. This can cause the ribosome to stall, resulting in truncated or non-functional proteins. Solutions include using a host strain engineered to supply rare tRNAs (e.g., Rosetta for E. coli) or having the gene synthesized with optimized codon usage [5] [6] [3].

Problem 2: Protein is Expressed but Insoluble (Inclusion Bodies)

You detect a strong band for your protein, but it's located in the pellet fraction after centrifugation, indicating the formation of inclusion bodies—aggregates of misfolded protein.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Slow Down Expression: Rapid expression can overwhelm the cell's folding machinery. Lowering the induction temperature (e.g., to 20-30°C) or reducing the concentration of the inducer (e.g., IPTG) can slow down translation, giving the protein more time to fold correctly [5] [3].

- Use Fusion Tags: Fusing your protein to a highly soluble partner like Maltose Binding Protein (MBP) or Thioredoxin (Trx) can greatly enhance solubility. Test both N-terminal and C-terminal fusions [5] [4].

- Co-express Chaperones: Co-expressing molecular chaperones (e.g., GroEL/GroES, DnaK/DnaJ) can assist in the proper folding of the target protein within the cell. Kits with chaperone plasmids are commercially available for this purpose [5] [3].

- Screen for Solubility: Always check for solubility by lysing the cells and centrifuging. The supernatant contains the soluble fraction, while the pellet contains the insoluble fraction. Re-suspend the pellet in buffer to the same volume as the supernatant to compare them via SDS-PAGE [5].

Problem 3: High Basal (Leaky) Expression or Protein Toxicity

The target protein is expressed even without induction, which can be toxic to the host cells, leading to poor cell growth, plasmid instability, or loss of the recombinant gene.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Tighten Promoter Control:

- For lac/T7-lac promoter systems, ensure your system has sufficient LacI repressor. Use host strains that carry the lacIq gene, which increases repressor production ten-fold, providing tighter control [4].

- For the common T7 system (e.g., in BL21(DE3) strains), basal expression comes from low-level activity of T7 RNA polymerase. Switch to a host that co-expresses T7 lysozyme (e.g., pLysS or lysY strains), which is a natural inhibitor of T7 RNA polymerase [4] [6].

- Use Tunable Expression Systems: For highly toxic proteins, use tightly regulated and tunable systems like the Lemo21(DE3) strain, where expression of the inhibitory T7 lysozyme is controlled by the rhamnose promoter. Titrating rhamnose concentration allows you to fine-tune the expression level of your toxic protein just below the host's toxicity threshold [4].

- Consider Cell-Free Expression: If the protein is extremely toxic to living cells, a cell-free protein synthesis system can be a viable alternative [4].

Problem 4: Protein Degradation

The full-length protein is degraded by host cell proteases, resulting in multiple smaller bands or a complete loss of the protein band on a western blot.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Use Protease-Deficient Strains: Use expression strains that lack key proteases like OmpT and Lon to minimize degradation during cell lysis and processing [4] [3].

- Add Protease Inhibitors: Always include a cocktail of protease inhibitors in your lysis buffer [3].

- Adjust Growth Conditions: Shorten the induction time or lower the induction temperature to reduce protease activity.

- Engineer the Protein: If the protein contains readily recognized degradation signals, consider removing these sequences through protein engineering to enhance stability [3].

Problem 5: Lack of Biological Activity

The protein is expressed and soluble but is not functionally active, which is often due to improper folding or missing post-translational modifications.

Potential Causes and Solutions:

- Promote Disulfide Bond Formation: If your protein requires disulfide bonds for stability or activity, the reducing cytoplasm of standard E. coli strains is not suitable. Use strains like Origami or SHuffle, which have mutations that promote disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm. SHuffle strains also express the disulfide bond isomerase DsbC in the cytoplasm to help correct misfolded bonds [5] [4].

- Switch Expression Systems: If your protein requires specific eukaryotic PTMs (e.g., complex glycosylation, gamma-carboxylation), a prokaryotic system like E. coli will not be sufficient. You must switch to a eukaryotic host such as yeast, insect, or mammalian cells [5] [2] [3].

- Test Fusion Tags: Sometimes, a fusion tag can interfere with the protein's active site or oligomerization. Test the protein's activity with the tag removed (using a protease cleavage site) or try a different tag configuration (e.g., switch from N-terminal to C-terminal) [5].

Essential Experimental Workflows

Standard Workflow for Testing Heterologous Expression in E. coli

This workflow provides a foundational methodology for establishing a protein expression experiment.

Decision Workflow for Troubleshooting Expression Problems

This logic diagram guides the troubleshooting process based on initial experimental observations.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

This table details essential materials and reagents used to address common challenges in heterologous expression.

Table 2: Essential Reagents for Heterologous Expression

| Reagent / Tool | Function / Purpose | Example Products / Strains |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized E. coli Strains | Engineered hosts to solve specific problems like codon bias, disulfide bond formation, or toxicity. | Rosetta: Supplies rare tRNAs for rare codons [5].Origami/SHuffle: Promotes cytoplasmic disulfide bond formation [5] [4].BL21(DE3) pLysS/T7 Express lysY: Provides T7 lysozyme for tight control of basal expression [4]. |

| Fusion Tags | Polypeptides fused to the target protein to aid in solubility, detection, and purification. | His-tag: Simplifies purification via immobilized metal affinity chromatography (IMAC) [7].MBP/GST-tag: Enhances solubility; also used for purification (amylose/glutathione resin) [5] [4].SUMO-tag: Enhances solubility and allows for highly specific cleavage [7]. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Kits | Co-expression plasmids for molecular chaperones that assist in the correct folding of the target protein inside the cell, reducing inclusion body formation. | Takara's Chaperone Plasmid Set [5]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Chemical mixtures added to lysis buffers to inhibit endogenous proteases released during cell disruption, preventing protein degradation. | Commercial cocktails (e.g., from Roche, Thermo Fisher) containing inhibitors for serine, cysteine, metallo, and aspartic proteases. |

| Tunable Induction Systems | Systems that allow precise control over the level of protein expression, crucial for expressing toxic proteins. | Lemo21(DE3) strain: Expression level is tuned with L-rhamnose concentration [4].Arabinose-inducible (pBAD) systems: Tightly regulated by arabinose [3]. |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1: What are the common causes of low recombinant protein expression in CHO cells and how can they be addressed? Low expression can stem from several factors related to vectors, promoters, and the host organism itself. A key issue is the use of suboptimal regulatory elements in the expression vector. Research has demonstrated that incorporating a Kozak sequence (GCCGCCRCC) upstream of the start codon can enhance translation initiation, while adding a Leader peptide sequence can improve protein folding and trafficking [8]. Combining these two elements has been shown to increase the expression of model proteins like eGFP by over 2-fold and secreted alkaline phosphatase (SEAP) by 1.55-fold compared to baseline vectors [8]. Furthermore, the site of transgene integration within the host genome is critical. Integration into transcriptionally inactive heterochromatin regions leads to silencing or low expression [9]. Strategies to overcome this include using Site-Specific Integration (SSI) systems like CRISPR-Cas9 to target "hotspot" genomic loci such as the Hprt1 gene, or employing chromatin opening elements like Scaffold/Matrix Attachment Regions (S/MARs) in the vector design to promote a more active chromatin state and stable expression [9] [10].

Q2: How can I reduce clonal heterogeneity and ensure stable protein production in recombinant CHO cell lines? Clonal heterogeneity, where different cell clones show vast differences in productivity and growth, is primarily caused by Random Transgene Integration (RTI) [9]. When a transgene integrates randomly, its expression is highly influenced by the local genomic environment. To address this, consider moving away from traditional RTI methods. Semi-Targeted Integration (STI) systems, such as the Sleeping Beauty or PiggyBac transposases, can improve the proportion of high-expressing clones and yield better productivity stability [9]. The most effective strategy is Site-Specific Integration (SSI) using CRISPR-based tools to insert the transgene into a predefined, transcriptionally active genomic "landing pad" [9]. This ensures that every selected clone has the transgene in the same favorable genetic context, drastically reducing heterogeneity. Additionally, for any chosen method, implementing a rigorous single-cell cloning and expansion protocol, followed by a Long-Term Culture (LTC) study to monitor for phenotypic drift over 55+ days, is crucial to identify the most stable production clones [9].

Q3: What strategies can improve CRISPR-Cas9 editing efficiency in difficult-to-transfect host cells like iPSCs or primary lymphocytes? Editing efficiency in sensitive primary cells like lymphocytes or finicky iPSCs can be enhanced by optimizing the delivery and nuclear localization of the CRISPR machinery. A proven strategy is using Hairpin Internal Nuclear Localization Signals (hiNLS) engineered directly into the backbone of the Cas9 protein [11]. This design increases the density of NLS sequences without hindering protein production, leading to more efficient import of the Cas9 ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complex into the nucleus. This approach has successfully enhanced gene knockout efficiency in primary human T cells compared to standard terminally-fused NLS constructs [11]. For iPSCs, which have notoriously low rates of Homology-Directed Repair (HDR), enriching for successfully transfected cells is key. This can be achieved by adding antibiotic selection or using Fluorescence-Activated Cell Sorting (FACS) to sort for cells that have taken up the editing components [12] [13].

Q4: How can I minimize off-target effects in CRISPR-based genome editing experiments? Minimizing off-target activity is critical for clean experimental results and therapeutic safety. The first line of defense is careful guide RNA (gRNA) design. Use established online tools to design highly specific gRNAs and scan for potential off-target sites in your specific genome [14]. Beyond design, employ high-fidelity Cas9 variants (e.g., HiFi Cas9) that have been engineered to drastically reduce off-target cleavage while maintaining robust on-target activity [14]. Finally, the choice of delivery method matters. Using pre-assembled Cas9 Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) complexes for editing, rather than plasmid DNA, limits the time the nuclease is active in the cell, thereby reducing the window for off-target cutting [11]. Always include proper controls, such as cells treated with a non-targeting gRNA, to accurately account for background noise and off-target effects in your analysis [14].

Troubleshooting Guides

Table 1: Troubleshooting Low Recombinant Protein Expression

| Problem Area | Potential Cause | Recommended Solution | Experimental Protocol to Test |

|---|---|---|---|

| Vector | Weak or unsuitable promoter | Use a strong, constitutive promoter (e.g., CMV) and validate its activity in your specific host cell type. | Clone your Gene of Interest (GOI) into a vector with a validated strong promoter. Transfert and measure mRNA (qPCR) and protein levels (ELISA/Western Blot) after 48h against a positive control. |

| Lack of enhancer elements | Incorporate regulatory elements like a Kozak sequence (GCCGCCRCC) and/or a Leader sequence upstream of the GOI [8]. | Construct vectors with the GOI alone, GOI+Kozak, and GOI+Kozak+Leader. Transfert in parallel and compare expression via flow cytometry (for fluorescent reporters) or specific activity assays over 72h [8]. | |

| Transgene Integration | Integration into silent heterochromatin | Employ Site-Specific Integration (SSI) into a known active locus (e.g., Hprt1) or use Bacterial Artificial Chromosomes (BACs) to include full regulatory loci [9] [10]. | Use CRISPR-Cas9 to target the GOI to a defined hotspot. Compare protein titer and clonal stability from SSI-derived clones versus those from Random Integration (RTI) over at least 15 passages. |

| Low copy number or gene silencing | Use a transposase-based Semi-Targeted Integration (STI) system (e.g., PiggyBac) to achieve higher, more stable copy numbers [9]. | Cotransfect the GOI plasmid with the transposase plasmid. Select pools and single clones. Use digital PCR to assess copy number and compare expression stability to RTI pools in a long-term culture study. | |

| Host Cell | Low transfection efficiency | Optimize delivery method. For CHO cells, test lipofection, electroporation, or different viral vectors [14] [10]. | Transfert cells with a GFP reporter plasmid using different methods/parameters. Analyze GFP positivity by flow cytometry at 24-48h to determine the most efficient protocol for your cell line. |

| Cellular stress / apoptosis | Engineer the host cell line to be more robust, e.g., by knocking out pro-apoptotic genes like Apaf1 to extend culture longevity and productivity [8]. | Use CRISPR-Cas9 to generate an Apaf1 knockout CHO cell line. Culture the KO and WT cells in production mode and compare viability (via Trypan Blue exclusion) and product titer at days 7, 10, and 14. |

Table 2: Quantitative Impact of Vector Optimization on Protein Expression

| Recombinant Protein | Regulatory Element Added | Expression Fold Change vs. Control | Key Experimental Finding |

|---|---|---|---|

| eGFP [8] | Kozak sequence | 1.26x | Increased translation initiation, measured by Mean Fluorescence Intensity (MFI) via flow cytometry. |

| eGFP [8] | Kozak + Leader sequence | 2.2x | Synergistic effect on translation and proper folding, measured by MFI. |

| SEAP (Transient) [8] | Kozak sequence | 1.37x | Elevated levels of secreted enzyme in culture supernatant, detected by enzymatic activity assay. |

| SEAP (Stable) [8] | Kozak + Leader sequence | 1.55x | Sustained higher yield in selected stable cell pools, confirming long-term benefit of element combination. |

Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Testing Regulatory Elements for Vector Optimization

This protocol outlines the steps to empirically test the effect of Kozak and Leader sequences on the expression of your gene of interest (GOI) in a mammalian cell system [8].

Workflow Diagram: Testing Regulatory Elements

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- Expression Vectors: Start with a standard mammalian expression vector (e.g., pcDNA3.1, pCMV-based).

- Cell Line: CHO-S or CHO-K1 cells are standard for recombinant protein production [10].

- Transfection Reagent: Use a high-efficiency reagent optimized for your cell line (e.g., Lipofectamine 3000) [12].

- Selection Antibiotic: e.g., Blasticidin, Puromycin, or G418, depending on the resistance marker in your vector.

- Analysis Kits: e.g., Alkaline phosphatase kit for SEAP, or specific ELISA kits for your GOI.

Methodology:

- Vector Construction: Clone your GOI into three variants of the backbone vector: (A) the basic vector with no added elements, (B) vector with a strong Kozak sequence (GCCGCCACC) added directly upstream of the start codon, and (C) vector with both the Kozak and a suitable Leader sequence [8]. Verify all constructs by sequencing.

- Cell Transfection: Culture CHO cells in an appropriate medium (e.g., DMEM/F12). Transfect the cells in parallel with the three constructed vectors using an optimized protocol. Include a mock transfection as a negative control.

- Transient Expression Analysis: 48 hours post-transfection, harvest the cell culture supernatant (for secreted proteins) or the cells themselves (for intracellular proteins). Quantify expression using a method suitable for your protein (e.g., fluorescence measurement for eGFP, enzymatic activity assay for SEAP, or ELISA) [8].

- Stable Cell Pool Generation: After transfection, passage the cells into a medium containing the appropriate selection antibiotic. Maintain the culture for 1-2 weeks, replenishing the selection medium every 2-3 days, to select for a stable pool of integrants.

- Stable Expression Analysis: Once a stable pool is established, assay the protein expression from the pools under standard production conditions. Compare the yield from the three different pools (A, B, and C) to determine the effect of the regulatory elements on long-term, stable production [8].

Protocol 2: Enhancing CRISPR Editing Efficiency with hiNLS Cas9

This protocol describes the use of novel Hairpin Internal Nuclear Localization Signal (hiNLS) Cas9 constructs to achieve higher editing rates in primary human cells, a common challenge in therapeutic development [11].

Workflow Diagram: hiNLS CRISPR Workflow

Key Research Reagent Solutions:

- CRISPR Nuclease: Use commercially available or research-provided hiNLS-Cas9 protein [11].

- Synthetic gRNA: Chemically synthesized crRNA and tracrRNA, or a single-guide RNA (sgRNA), designed for your specific genomic target.

- Delivery System: Electroporator system (e.g., Neon, Amaxa) for efficient RNP delivery into primary cells [11].

- Genotyping Detection Kit: T7 Endonuclease I assay kit or materials for Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) library prep and analysis.

Methodology:

- RNP Complex Assembly: Complex the purified hiNLS-Cas9 protein with the synthesized target gRNA at a predetermined molar ratio in a suitable buffer. Incubate for 10-20 minutes at room temperature to form the active RNP complex.

- Cell Preparation and Delivery: Harvest and wash the primary cells (e.g., T cells). Resuspend the cells in the appropriate electroporation buffer. Mix the cell suspension with the pre-assembled RNP complex and electroporate using optimized parameters for your cell type [11].

- Post-Transfection Culture: Immediately after electroporation, transfer the cells to pre-warmed culture medium. Allow the cells to recover and the editing to occur for 48-72 hours.

- Editing Efficiency Analysis: Harvest the genomic DNA from the edited cells. Amplify the target genomic region by PCR. Quantify the editing efficiency using the T7 Endonuclease I (T7E1) assay, which cleaves heteroduplex DNA formed by edited and wild-type sequences, or through Next-Generation Sequencing (NGS) for a more precise and quantitative measurement [14] [12]. Compare the efficiency achieved with hiNLS-Cas9 to that of standard NLS-Cas9 constructs.

The Scientist's Toolkit

Table 3: Essential Reagents for Heterologous Expression and Genome Engineering

| Reagent / Solution | Function / Application | Example(s) |

|---|---|---|

| Kozak Sequence | A nucleotide sequence (GCCGCCRCC) that enhances the initiation of translation in eukaryotic cells by ensuring accurate ribosome binding [8]. | GCCGCCACC |

| Leader Sequence | A peptide sequence that directs the nascent protein to the secretory pathway, aiding in proper folding and post-translational modification, and is often cleaved from the mature protein [8]. | Native secretion signal peptides (e.g., from IL-2) |

| Site-Specific Integration (SSI) Systems | Enables precise insertion of a transgene into a predefined, transcriptionally active genomic locus, reducing clonal heterogeneity [9]. | CRISPR-Cas9, Cre-loxP, Bxb1 integrase |

| Semi-Targeted Integration (STI) Systems | Transposase-based systems that facilitate higher integration efficiency into transcriptionally active regions compared to random integration, without requiring a predefined site [9]. | PiggyBac, Sleeping Beauty transposases |

| High-Fidelity Cas9 | Engineered Cas9 variants with reduced off-target cleavage activity, crucial for applications requiring high specificity, such as therapeutic development [14]. | HiFi Cas9, eSpCas9 |

| Hairpin Internal NLS (hiNLS) | Engineered nuclear localization signals placed within a protein's structure to increase nuclear import density and efficiency, boosting editing rates in primary cells [11]. | hiNLS-Cas9 constructs |

| Ribonucleoprotein (RNP) Complex | A pre-assembled complex of Cas9 protein and guide RNA, delivered directly into cells. Offers high efficiency, rapid action, and reduced off-target effects compared to plasmid DNA delivery [11]. | Cas9 protein + sgRNA complexed in vitro |

| Chromatin Opening Elements | DNA elements (e.g., S/MARs) included in vectors to help maintain an open, transcriptionally active chromatin state at the integration site, promoting stable transgene expression [10]. | Scaffold/Matrix Attachment Regions (S/MARs) |

Troubleshooting Guides

Insoluble Aggregate Formation

Q: My target protein is expressed but forms insoluble aggregates (inclusion bodies). What strategies can I use to improve solubility?

A: Insoluble aggregation often occurs when proteins misfold or hydrophobic residues are exposed. A multi-pronged approach is needed to address this.

- Modify Expression Conditions: Slowing down the expression rate allows the cellular folding machinery to keep up. You can achieve this by:

- Utilize Fusion Tags: Fusing your protein to a highly soluble partner can dramatically improve its solubility. A common and effective tag is Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) [5] [15] [16]. Test both N- and C-terminal fusions, as the optimal configuration can be protein-specific. A case study showed that adding an MBP tag led to a strong increase in protein yield for a viral coat protein with known solubility issues, whereas expression without the tag was barely detectable [16].

- Employ Chaperone Co-expression: Co-express molecular chaperones, such as GroEL/S, DnaK/DnaJ, or ClpB, to assist with proper protein folding inside the cell. Kits are available that provide plasmids for co-expressing specific chaperone sets [5] [15].

- Address Disulfide Bonds: If your protein requires disulfide bonds for stability, use engineered E. coli strains like SHuffle or Origami. These strains have a more oxidizing cytoplasm that facilitates the formation of correct disulfide bonds [5] [15].

- Analyze the Mechanism: Understand that aggregates are typically stabilized by non-covalent forces. Hydrophobic interactions are the main driving force, while hydrogen bonding and van der Waals forces also contribute to structural stability. In some cases, disulfide bonds can also play a role in aggregation [17].

Table: Strategies to Combat Insoluble Aggregates

| Strategy | Method Example | Key Mechanism |

|---|---|---|

| Process Modulation | Lower temperature (15-20°C), reduce inducer concentration [5] [15] | Slows synthesis rate for proper folding |

| Genetic Fusion | MBP, Thioredoxin, or SUMO solubility tags [5] [16] | Enhances solubility of passenger protein |

| Chaperone Co-expression | Plasmids for GroEL/S, DnaK/DnaJ complexes [5] [15] | Increases cellular folding capacity |

| Specialized Strains | SHuffle (disulfide bonds), Rosetta (rare codons) [5] [15] | Corrects specific folding deficiencies |

Proteolysis and Protein Degradation

Q: I see multiple lower molecular weight bands on my Western blot, suggesting proteolysis. How can I minimize degradation of my recombinant protein?

A: Proteolysis indicates that host cell proteases are cleaving your target protein.

- Select a Protease-Deficient Strain: Always use expression strains that lack key proteases. Look for strains with mutations in genes like ompT (outer membrane protease) and lon (cytoplasmic protease) [15]. Common E.coli strains like BL21(DE3) are often deficient in these proteases.

- Work at Low Temperatures: Perform cell lysis and all subsequent purification steps on ice or at 4°C. Always include a broad-spectrum protease inhibitor cocktail in your lysis buffer [15].

- Consider the Protein's Destination: For proteins that naturally form disulfide bonds, targeting them to the oxidative environment of the periplasm can be beneficial. Use expression vectors that include a signal sequence (e.g., pelB, DsbA) for periplasmic secretion [15].

- Shorten Experiment Time: If degradation persists, try to shorten the time between induction and harvest, as the stress of recombinant protein production can upregulate protease activity.

Low Protein Yields

Q: I am getting very low yields of my target protein. What are the primary factors I should investigate?

A: Low yields can stem from problems at the transcriptional, translational, or post-translational level.

- Verify Your DNA Construct: The first step is always to sequence the entire expression cassette to ensure there are no accidental mutations, stray stop codons, or errors in the ribosomal binding site (RBS) [5].

- Check for Rare Codons: Analyze the codon usage of your gene. If it contains codons that are rare in your expression host (e.g., E. coli), the translation will stall. This can be resolved by using strains like Rosetta that carry extra copies of rare tRNA genes, or by having the gene synthesized using host-optimized codons [5] [15].

- Troubleshoot Low Basal Expression: For toxic proteins, even low levels of "leaky" expression before induction can inhibit cell growth and plasmid stability.

- In IPTG-inducible T7 systems (e.g., BL21(DE3)), use strains that co-express T7 Lysozyme (e.g., pLysS strains or T7 Express lysY), which is a natural inhibitor of T7 RNA polymerase [15].

- Ensure sufficient levels of the Lac repressor by using strains with the lacIq allele, which produces more repressor protein [15].

- Optimize Culture Conditions: The culture medium and growth conditions are critical cost drivers and significantly impact yield [18]. Optimization involves:

- Medium Composition: Use a well-defined medium and experiment with carbon sources and key nutrients. Statistical design of experiments (DoE) can efficiently identify optimal concentrations [18].

- Process Parameters: Carefully control and optimize pH, dissolved oxygen levels, and feeding strategies in bioreactors [18].

Table: Culture Condition Optimization for Improved Yield

| Parameter | Potential Impact | Optimization Approach |

|---|---|---|

| Medium Composition | Accounts for up to 80% of production cost; affects nutrient availability and physicochemical environment [18] | High-throughput screening, Statistical Design of Experiments (DoE), AI/ML-driven modeling [18] |

| pH | Influences protein stability, fragmentation, and charge variants [18] | Controlled feedback loops in bioreactors |

| Dissolved Oxygen | Critical for cell health and proper protein folding; low oxygen can lead to aggregation [18] | Cascade control of air/O2/N2 gas mixing |

| Temperature | Affects growth rate, expression rate, and folding efficiency [5] [15] | Test a range (e.g., 15°C, 25°C, 37°C) |

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q: When should I consider switching to a different expression system? A: Consider switching if you have exhaustively tried the strategies above in E. coli without success. This is particularly true for complex proteins that require post-translational modifications (e.g., specific glycosylation patterns), are highly disulfide-bonded, or are toxic to bacterial cells. Alternative systems include:

- Insect Cells (Sf9, Sf21): Use the baculovirus expression system (BEVS) for producing more complex eukaryotic proteins [19].

- Mammalian Cells: The preferred choice for therapeutic proteins requiring human-like glycosylation [18].

- Cell-Free Systems: Useful for toxic proteins or for rapid screening. Platforms like ALiCE can produce proteins within 24 hours and are excellent for testing different tags and constructs [16].

Q: What is the quickest way to test if a solubility tag will help my protein? A: The fastest approach is to use a cell-free protein expression system. These systems, such as ALiCE, allow you to test multiple constructs (e.g., with and without an MBP tag) in parallel within a single day, bypassing the time-consuming steps of bacterial transformation and culture growth [16].

Q: Are there emerging technologies that can help with these challenges? A: Yes, the field is rapidly advancing. Key trends include:

- AI-Driven Protein Engineering: AI and machine learning are now used to accurately model protein structures, optimize stability, and reduce immunogenicity [20].

- Advanced Modeling for Culture Optimization: Artificial Intelligence and Machine Learning (AI/ML) are being integrated to model the complex relationships between medium components and protein yield, accelerating optimization [18].

- Novel Delivery Systems: Research into nanocarriers and cell-penetrating peptides aims to improve the delivery of protein drugs, which can influence the design criteria for expression [20].

Experimental Workflow: A Systematic Approach to Troubleshooting

The following diagram outlines a logical workflow for diagnosing and addressing common heterologous expression challenges.

The Scientist's Toolkit: Key Research Reagent Solutions

Table: Essential Reagents for Troubleshooting Heterologous Expression

| Reagent / Material | Function in Troubleshooting | Example Use Cases |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized E. coli Strains | Provides a tailored cellular environment for expression. | SHuffle: For disulfide-bonded proteins [5] [15]. Rosetta 2: Supplies tRNAs for rare codons [5] [15]. BL21(DE3) pLysS: For tight control of basal expression [15]. |

| Solubility Enhancement Tags | Improves solubility and folding of the target protein. | MBP (Maltose-Binding Protein): A highly effective, large solubility tag [5] [16]. SUMO: Also acts as a chaperone and can be cleaved with high specificity. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Sets | Co-expression of folding assistants to improve yield of soluble protein. | Takara's Chaperone Plasmid Set: Allows for co-expression of GroEL/S, DnaK/DnaJ, etc., to test which complex aids your protein [5]. |

| Cell-Free Protein Synthesis Kit | Rapidly test constructs without live cells; useful for toxic proteins. | PURExpress Kit (NEB): Recombinant system for in vitro expression [15]. ALiCE (LenioBio): Eukaryotic-based system for rapid screening of tags and constructs [16]. |

| Protease Inhibitor Cocktails | Prevents proteolytic degradation during cell lysis and purification. | Added to lysis buffer when using non-protease-deficient strains or when degradation is suspected [15]. |

System Comparison and Selection Guide

Selecting the appropriate protein expression system is a critical first step in experimental design. The table below summarizes the core characteristics of E. coli and yeast systems to guide this decision.

| Feature | E. coli (Prokaryotic) | Yeast (Eukaryotic) |

|---|---|---|

| Growth Rate | Very fast (doubling time ~20-30 min) [21] [22] | Moderate (doubling time ~90 min - 2 hours) [21] [22] |

| Cost & Complexity | Low cost; simple growth medium [23] [21] [24] | Low cost; simple to medium complexity [21] [25] |

| Post-Translational Modifications | None or minimal (e.g., no glycosylation) [21] [24] [22] | Capable of many (e.g., glycosylation, disulfide bond formation) [21] [24] [25] |

| Typical Protein Localization | Primarily intracellular (can form inclusion bodies) [21] [24] | Can be secreted into the medium or intracellular [21] [25] |

| Common Yields | High [23] [21] | Low to High [21] |

| Glycosylation Pattern | Not applicable | High-mannose type; can differ from mammalian patterns (may be hyperglycosylation in S. cerevisiae) [21] |

| Genetic Manipulation | Easy; very mature and standardized tools [23] [24] | Easy to medium complexity [21] [25] |

| Ideal For | Simple proteins not requiring eukaryotic PTMs; rapid, low-cost production [24] [22] | Proteins requiring eukaryotic-like folding and PTMs; secreted production [24] [25] |

Troubleshooting FAQs and Guides

Frequently Asked Questions

Q1: I see no protein expression in my E. coli culture after induction. What should I check?

- Verify your construct: Sequence the expression cassette to ensure there are no unintended stop codons or frame shifts [26] [5].

- Check for protein toxicity: If your gene of interest is toxic to the host, use tighter regulation systems like BL21(DE3)pLysS or BL21-AI strains, and consider adding glucose to the medium to repress basal expression [26].

- Confirm antibiotic selection: If using ampicillin, it can degrade during culture. Substitute with the more stable carbenicillin to maintain plasmid selection pressure [26].

- Assess solubility: Your protein may be expressed but insoluble. Centrifuge the lysate and analyze both the supernatant (soluble fraction) and the resuspended pellet (insoluble fraction) by SDS-PAGE [5].

Q2: My target protein is expressed in E. coli but forms inclusion bodies. How can I improve solubility?

- Lower induction temperature: Reduce the temperature to 30°C, 25°C, or even 18°C during induction. Lower temperatures slow down protein synthesis, allowing more time for proper folding [26].

- Reduce inducer concentration: Use a lower amount of IPTG (e.g., 0.1 - 1 mM) to moderate the expression rate [26] [5].

- Co-express chaperones: Co-express molecular chaperones (e.g., using commercial chaperone plasmid sets) to assist with protein folding [5].

- Use fusion tags: Fuse your protein to highly soluble partners like Maltose Binding Protein (MBP) or thioredoxin to enhance solubility [5].

Q3: I am getting low transformation efficiency in my Pichia pastoris system. What could be wrong?

- Use log-phase cells: Ensure cells are harvested during log-phase growth (OD600 generally below 1.0) for making competent cells [27].

- Check reagent pH and freshness: The pH of transformation solutions should be at 8.0. Prepare the PEG solution fresh each time [27].

- Increase DNA amount and incubation time: Use more linearized DNA and consider extending the incubation time during the transformation process to up to 3 hours [27].

Q4: My protein yield in yeast is low, even though the gene is integrated. What are potential causes?

- Check codon usage: The heterologous gene may contain codons that are rare in your yeast host. Consider using codon-optimized gene synthesis or specialized host strains [26] [5].

- Proteolytic degradation: Proteases in the culture medium may be degrading your secreted protein. Use protease-deficient host strains and add compatible protease inhibitors to the culture medium [26] [21].

- Optimize secretion: If secreting the protein, test different secretion signal sequences (e.g., the α-mating factor pre-sequence) to find the most efficient one for your target protein [21].

Experimental Troubleshooting Workflow

The following diagram outlines a logical, step-by-step approach to diagnosing and resolving common issues in heterologous protein expression.

Essential Reagents and Tools

The table below catalogs key reagents and materials frequently used to address common problems in E. coli and yeast expression systems.

| Reagent / Tool | Function | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| BL21(DE3) pLysS/E Strains [26] | Tighter regulation of T7 RNA polymerase; reduces basal expression. | Expressing proteins toxic to E. coli. |

| BL21-AI Strain [26] | Expression is induced by arabinose, offering very tight control. | An alternative for expressing toxic proteins in E. coli. |

| Chaperone Plasmid Sets [5] | Overexpress specific molecular chaperones (e.g., GroEL/GroES). | Improving folding and solubility of complex proteins in E. coli. |

| SHuffle / Origami Strains [5] | Promote disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm. | Expressing proteins that require correct disulfide bonding in E. coli. |

| Rosetta Strain [5] | Supplies tRNAs for codons rarely used in E. coli. | Expressing genes with codons not optimal for E. coli. |

| Protease-deficient Yeast Strains [21] | Reduce proteolytic degradation of the target protein. | Increasing yield of secreted proteins in yeast systems. |

| PichiaPink System [21] | A suite of strains and vectors for optimized expression in P. pastoris. | High-yield secretion of recombinant proteins with options to combat toxicity. |

| Various Secretion Signals [21] | Leader sequences to direct protein secretion (e.g., α-mating factor). | Finding the most efficient signal to secrete a target protein from yeast. |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Testing for Solubility and Small-Scale Expression Optimization in E. coli

This protocol is essential when initial expression attempts fail or when a protein is suspected to be insoluble [5].

- Transformation and Growth: Transform your expression plasmid into an appropriate E. coli host strain (e.g., BL21(DE3)). Plate on selective media and incubate overnight at 37°C.

- Inoculate Cultures: Inoculate 2-5 mL of autoinduction media or LB with antibiotic with a single fresh colony. Grow at the appropriate temperature (e.g., 37°C) with shaking until the OD600 reaches ~0.5.

- Induce Expression: Add IPTG to a final concentration (e.g., 0.1 mM, 0.5 mM, 1.0 mM). For temperature testing, split the culture into smaller aliquots and induce at different temperatures (e.g., 37°C, 25°C, 18°C). Continue shaking for 3-4 hours or overnight for lower temperatures.

- Harvest and Lysis: Pellet 1 mL of each culture by centrifugation. Resuspend the cell pellets in 100 µL of lysis buffer (e.g., with lysozyme) and incubate on ice for 15-30 minutes. Lyse cells by sonication or freeze-thaw cycles.

- Fractionation: Centrifuge the lysate at high speed (e.g., >12,000 x g) for 10-15 minutes at 4°C.

- Analysis: Carefully transfer the supernatant (soluble fraction) to a new tube. Resuspend the pellet (insoluble fraction) in 100 µL of SDS-PAGE loading buffer. Analyze equal proportions of the total, soluble, and insoluble fractions by SDS-PAGE to determine expression level and solubility.

Protocol 2: Diagnostic Colony PCR for Yeast Transformants

This protocol confirms the successful integration of an expression cassette into the yeast genome [27].

- Pick Colonies: Using a sterile pipette tip, pick a small portion of a putative yeast transformant colony.

- Prepare Template: Resuspend the cells in 20 µL of a lysis solution (e.g., 20 mM NaOH, 0.1% SDS) and incubate at 95-100°C for 10-15 minutes to lyse the cells and release genomic DNA. Centrifuge briefly to pellet cell debris.

- Set Up PCR: Use 1-2 µL of the supernatant as a template in a standard PCR reaction. The primers should be designed to flank the intended integration site or to amplify a product spanning the junction between the host genome and the integrated cassette.

- Run PCR: Perform PCR using a standard thermocycling program suitable for your primer pair and expected product size.

- Analyze: Run the PCR products on an agarose gel. A band of the expected size confirms correct integration, while no band suggests a failed transformation or incorrect integration.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

FAQ 1: What are the first steps to take when my recombinant protein is not expressing at all? The initial troubleshooting should focus on verifying your vector, host strain, and growth conditions.

- Vector: Ensure your gene of interest is in-frame after cloning by sequencing the plasmid. Check the sequence for long stretches of rare codons, which can cause truncation, and consider using a host strain engineered to express rare tRNAs. Also, avoid high GC content at the 5' end of the gene, as this can affect mRNA stability [28].

- Host Strain: Confirm that your chosen host strain is appropriate for your expression system (e.g., a T7 RNA polymerase-expressing strain for a T7 promoter-based vector) [29] [28].

- Growth Conditions: Perform an expression time course, taking samples every hour after induction. Test different induction temperatures (e.g., 30°C vs. 37°C) and inducer concentrations, as IPTG can be toxic at high levels [28].

FAQ 2: How can I prevent "leaky" basal expression of a toxic protein? High basal (uninduced) expression can inhibit cell growth or cause plasmid loss.

- For T7-based systems (e.g., in BL21(DE3)), use hosts that co-express T7 Lysozyme (e.g., pLysS/LysY strains), which inhibits T7 RNA polymerase [29] [28].

- Use host strains with enhanced repressor production, such as those carrying the lacIq gene, for tighter control of lac-derived promoters [29].

- Consider strains with lower basal T7 RNA polymerase production, such as T7 Express strains, which use a wild-type lac promoter instead of lacUV5 [29].

FAQ 3: My protein is expressed but is insoluble. What strategies can I use to improve solubility? If your protein forms inclusion bodies, several approaches can promote soluble expression.

- Lower Induction Temperature: Induce protein expression at a lower temperature, typically between 15–20°C [29].

- Use a Solubility Tag: Fuse your protein to a solubility tag like Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) using systems like the pMAL Protein Fusion and Purification System. These tags can enhance solubility and allow for purification [29].

- Co-express Chaperones: Co-express molecular chaperones such as GroEL, DnaK, or ClpB to assist with proper folding in vivo [29].

FAQ 4: What specific solutions are available for expressing membrane proteins? Membrane proteins require specialized hosts and strategies for proper integration and folding.

- Tunable Expression Systems: Use systems like the Lemo21(DE3) strain, which allows for precise control of expression levels by titrating the concentration of L-rhamnose. This helps to avoid saturation of the membrane insertion machinery [29] [30].

- Specialized Strains: Employ strains engineered for disulfide bond formation, such as SHuffle strains, if your membrane protein requires correct cysteine pairing [29].

FAQ 5: How can I achieve proper disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm? The E. coli cytoplasm is a reducing environment, which inhibits disulfide bond formation.

- Use engineered strains like SHuffle strains, which have a mutated thioredoxin reductase pathway that allows for disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm. These strains also express the disulfide bond isomerase DsbC in the cytoplasm to correct mis-oxidized proteins [29].

Troubleshooting Guide

The table below summarizes common problems, their potential causes, and recommended solutions.

| Problem Category | Specific Symptom | Possible Cause | Recommended Solution |

|---|---|---|---|

| Low or No Expression | No protein band on SDS-PAGE | Gene sequence errors, rare codons, or mRNA instability | Sequence plasmid; use rare tRNA strains (e.g., Rosetta); check GC content [28] |

| Incorrect host strain for vector system | Use T7-compatible strains (e.g., BL21(DE3)) for T7 promoters [29] | ||

| Suboptimal growth/induction conditions | Perform a time course; test temperatures (16°C-30°C) and IPTG concentrations [31] [28] | ||

| Toxic Protein Expression | Poor cell growth, plasmid instability | Leaky basal expression before induction | Use strains with tighter repression (lacIq, pLysS/LysY, T7 Express) [29] [28] |

| Overwhelming expression upon induction | Use a tunable system (e.g., Lemo21(DE3)) [29] or switch to a cell-free system [29] [32] | ||

| Solubility & Folding Issues | Protein in inclusion bodies | Aggregation due to rapid expression | Reduce induction temperature (15-20°C); use solubility tags (e.g., MBP) [29] |

| Lack of proper folding assistance | Co-express chaperones (GroEL, DnaK) [29] | ||

| Incorrect disulfide bonds | Reducing environment of cytoplasm | Use SHuffle strains for cytoplasmic disulfide bond formation [29] | |

| Membrane Protein Challenges | Low yield, misfolded protein | Saturation of membrane insertion machinery | Use tunable expression (Lemo21(DE3)) to control expression rate [29] |

Detailed Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: High-Throughput Screening for Soluble Expression

This protocol is adapted for a 96-well plate format to rapidly screen multiple constructs or conditions [31].

Key Materials:

- Expression Vector: e.g., pMCSG53 (with cleavable N-terminal 6xHis-tag) [31].

- Competent E. coli: High-throughput competent cells (e.g., BL21(DE3) or derivatives) [31].

- Media: Luria-Bertani (LB) broth with appropriate antibiotics.

- Inducer: Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG).

- Lysis Buffer: e.g., Tris-based buffer with lysozyme and/or detergents.

- Equipment: 96-well deep-well plates, microplate shaker/incubator, centrifuge with plate rotor.

Methodology:

- Transformation: Transform commercially synthesized, codon-optimized plasmid clones into high-efficiency competent E. coli directly in a 96-well plate format [31].

- Expression Culture: Inoculate 1-2 mL of LB medium in a deep-well plate with single colonies. Grow at 37°C with shaking until mid-log phase (OD600 ~0.6-0.8).

- Induction: Induce protein expression by adding IPTG to a final concentration of 200 µM. Incubate with shaking at 25°C overnight (~16-20 hours) [31].

- Harvesting and Lysis: Centrifuge plates to pellet cells. Resuspend pellets in a suitable lysis buffer (e.g., containing lysozyme). Perform freeze-thaw cycles or use chemical lysis to disrupt cells.

- Solubility Analysis: Centrifuge the lysates to separate soluble (supernatant) and insoluble (pellet) fractions. Analyze both fractions by SDS-PAGE or use a method compatible with His-tag detection to assess the amount of soluble target protein.

Protocol 2: Tunable Expression for Toxic and Membrane Proteins

This protocol uses the Lemo21(DE3) strain to fine-tune expression levels by varying L-rhamnose concentration [29].

Key Materials:

- Host Strain: Lemo21(DE3) competent cells.

- Inducers: IPTG and L-Rhamnose.

- Media: LB or defined medium.

Methodology:

- Transformation: Transform your expression plasmid into the Lemo21(DE3) strain.

- Setting up Expression Trials: Inoculate multiple cultures and grow them to mid-log phase.

- Titration of Expression: To each culture, add a different concentration of L-rhamnose, ranging from 0 µM to 2000 µM. Then, induce with a fixed concentration of IPTG [29].

- Analysis: Incubate the cultures post-induction for the desired time. Monitor cell growth (OD600) and analyze protein expression and solubility (via SDS-PAGE) for each condition. The optimal L-rhamnose concentration is the one that maximizes soluble yield while maintaining healthy cell growth.

Experimental Workflow and Pathways

The following diagram illustrates a systematic troubleshooting workflow for heterologous protein expression.

Systematic Troubleshooting Workflow for Heterologous Protein Expression

The Scientist's Toolkit: Research Reagent Solutions

This table details key reagents and their functions for troubleshooting heterologous expression.

| Reagent / Material | Function / Application | Examples / Notes |

|---|---|---|

| Specialized E. coli Strains | Engineered hosts to overcome specific hurdles. | BL21(DE3) pLysS/LysY: For toxic proteins, reduces basal T7 expression [29] [28]. SHuffle: For disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm [29]. Lemo21(DE3): For tunable expression of toxic/membrane proteins [29]. Rosetta: Supplies rare tRNAs for genes with non-optimal codon usage [28]. |

| Expression Vectors with Tags | Vectors designed to enhance solubility and simplify purification. | pMAL Vectors: Fuse protein to Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) to improve solubility [29]. pMCSG53: Vector with a cleavable N-terminal 6xHis-tag for purification [31]. |

| Inducers & Inhibitors | Chemicals to control expression and prevent degradation. | IPTG: Inducer for lac/T7-lac systems [33]. L-Rhamnose: Used for tunable induction in systems like Lemo21(DE3) [29]. Protease Inhibitor Cocktail: Added during cell lysis to prevent protein degradation [29] [33]. |

| Culture Media | Nutrient sources for cell growth and protein production. | LB (Lysogeny Broth): Standard rich medium [33] [31]. Terrific Broth (TB): High-density growth for increased yield [33]. Defined/Minimal Media (e.g., M9): For isotope labeling or metabolic studies [33]. |

| Lysis & Purification Reagents | For cell disruption and protein isolation. | Lysis Buffers: Typically Tris- or phosphate-based, with lysozyme (for bacteria) and detergents [33]. IMAC Resins: For purifying His-tagged proteins (e.g., Ni-NTA) [33]. Amylose Resin: For purifying MBP-fusion proteins [29]. |

Strategic Implementation: Host Selection, Vector Design, and Expression Optimization

FAQs: Selecting and Troubleshooting Your Expression System

Q1: What are the four key questions to ask when selecting a gene expression system?

A systematic approach is recommended, starting with four key questions about your protein of interest [34]:

- What is the biological source of the protein? Prokaryotic proteins often express well in E. coli, whereas eukaryotic proteins typically require eukaryotic hosts.

- Is the protein secreted or intracellular in its native source? This influences the choice of secretion signals and cellular compartment for expression (e.g., targeting the periplasm in E. coli).

- What is the protein's size and structural complexity? Large, multi-domain proteins or those with complex quaternary structures often require the sophisticated folding machinery of insect or mammalian cells [34] [35].

- Does the protein require post-translational modifications (PTMs) for functionality? If yes, the type of PTM (e.g., glycosylation, disulfide bonds) will dictate the host. E. coli cannot perform complex glycosylation, while yeast, insect, and mammalian cells offer varying capabilities [34] [36].

Q2: My protein is toxic to the host cells. What strategies can I use?

Protein toxicity can stunt cell growth and drastically reduce yields [3]. Several proven solutions exist:

- Use Tightly Controlled Inducible Systems: Systems such as the lac operon, T7 lac, or arabinose-inducible (pBAD) promoters allow you to grow the cells to a robust density before inducing expression [3] [37]. For the T7 system in E. coli, using strains that express T7 lysozyme (e.g., pLysS or lysY strains) can effectively inhibit basal expression before induction [37].

- Employ Tunable Expression Systems: For fine-grained control, systems like the rhamnose-inducible PrhaBAD promoter allow you to titrate expression levels by varying the inducer concentration, keeping the toxic protein just below the host's tolerance threshold [37].

- Switch to Low-Copy Number Plasmids: These plasmids reduce the gene dosage, slowing down protein production and mitigating toxicity [3].

- Consider a Cell-Free System: For highly toxic proteins, cell-free expression systems completely bypass cell viability issues [37].

Q3: My protein is expressed but forms inclusion bodies. How can I improve solubility?

The formation of insoluble inclusion bodies is a common challenge, especially in E. coli [3]. You can address this by:

- Lowering the Expression Temperature: Reducing the temperature (e.g., to 20–30°C) upon induction slows down translation, giving the protein more time to fold correctly [3] [37].

- Using Fusion Tags: Tags like Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP) or Glutathione-S-Transferase (GST) can enhance solubility and prevent misfolding [3] [37].

- Co-expressing Molecular Chaperones: Co-expression of chaperone systems like GroEL/GroES or DnaK/DnaJ can assist in proper protein folding [3].

- Using Specialized Strains: Strains like SHuffle are engineered for disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm and can aid in the folding of complex proteins [37].

Q4: I am not getting any protein expression. What could be wrong?

- Codon Mismatch: The gene may contain rare codons for your host organism, causing translational stalling. Solution: Perform codon optimization of the gene sequence to match the tRNA pool of your host [3] [38].

- Poor Transcriptional Initiation: Weak promoters or inefficient ribosomal binding sites (RBS) can limit expression. Solution: Use strong, well-characterized promoters (e.g., T7, AOX1 for P. pastoris) and ensure optimal Kozak (eukaryotes) or Shine-Dalgarno (prokaryotes) sequences [8] [38].

- mRNA Secondary Structure: Stable structures in the 5' UTR can prevent ribosome binding. Solution: Re-engineer the sequence to avoid such structures [37].

- Protein Degradation: Your protein may be degraded by host proteases. Solution: Use protease-deficient host strains (e.g., BL21(DE3) for E. coli) and add protease inhibitors during lysis and purification [3] [37].

Troubleshooting Guides

Guide to Common Protein Expression Challenges

The table below summarizes frequent problems, their likely causes, and proven solutions.

| Challenge | Root Cause | Proven Solutions |

|---|---|---|

| Low or No Yield [3] [37] | Codon bias; mRNA secondary structure; weak promoter; protein degradation. | Codon optimization; optimize 5' UTR/RBS; use stronger promoter; use protease-deficient strains and inhibitors. |

| Inclusion Body Formation [3] [37] | Misfolding in high-expression prokaryotic systems; reducing cytoplasm. | Lower expression temperature (15-30°C); use fusion tags (MBP, GST); co-express chaperones; use engineered strains (e.g., SHuffle). |

| Host Cell Toxicity [3] [37] | Protein function inhibits host growth. | Use tightly controlled inducible systems (e.g., pLysS, rhamnose-inducible); use low-copy plasmids; induce at high cell density; switch to cell-free systems. |

| Incorrect PTMs / Lack of Activity [34] [36] | Prokaryotic host cannot perform essential eukaryotic modifications (e.g., glycosylation). | Switch to eukaryotic host: yeast, insect, or mammalian cells based on PTM complexity required. |

| Protein Degradation [3] | Recognition by host proteases; inherent instability. | Use protease-deficient strains; add protease inhibitors; engineer protein to remove degradation signals. |

Quantitative Comparison of Major Expression Systems

Selecting the right host is critical. The following table provides a comparative overview of the most common systems to guide your decision.

| Expression System | Typical Yield (mg/L) | Timeline | Key Advantages | Major Limitations | Ideal For |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| E. coli [36] | Varies widely; can be very high | 2-3 weeks | Low cost, fast growth, high yield, simple scale-up | No complex PTMs, high risk of inclusion bodies, codon bias | Non-glycosylated proteins, enzymes, structural biology targets |

| S. cerevisiae (Yeast) [39] | Up to gram-scale for some proteins [39] | 3-4 weeks | GRAS status, eukaryotic PTMs (simpler glycosylation), secretion | Hyper-mannosylation can be immunogenic, lower yields for some proteins | Industrial enzymes, some therapeutic proteins (e.g., insulin, hepatitis vaccine) |

| Insect Cells (Baculovirus) [36] | 1-500 | 6-8 weeks | Complex PTMs, proper folding for large eukaryotic proteins | Production slower than E. coli, non-human glycosylation | Membrane proteins, viral antigens, multi-subunit complexes |

| Mammalian Cells (CHO, HEK293) [8] [36] | 10-5000 (process-dependent) | 4-6 weeks (transient); months (stable) | Full human-like PTMs, high biological activity, correct folding | Highest cost, longest timeline, technically demanding | Therapeutic antibodies, complex glycoproteins, receptors |

Experimental Protocols for Key Methodologies

Protocol: CRISPR/Cas9-Mediated Genomic Integration in a Fungal Chassis

This protocol, adapted from a 2025 study on engineering Aspergillus niger, details the creation of a clean chassis strain for high-yield heterologous protein production [40].

Principle: To minimize background secretion and free up genomic "hotspots" for target gene integration by deleting multiple copies of a native highly expressed gene (e.g., glucoamylase, TeGlaA) and a major extracellular protease (PepA).

Materials:

- Host Strain: Industrial A. niger strain AnN1 (or equivalent with high secretory capacity).

- Plasmids: CRISPR/Cas9 plasmid expressing a tailored sgRNA.

- Donor DNA: Linear DNA fragments containing homologous arms for gene deletion and a selectable marker.

- Reagents: Protoplast transformation reagents (osmotic stabilizers, lytic enzymes), selection antibiotics, PCR reagents for verification.

Procedure:

- sgRNA Design: Design sgRNAs targeting the conserved regions of the tandemly repeated native gene (TeGlaA).

- Donor DNA Construction: Synthesize a donor DNA cassette containing a selectable marker (e.g., hygromycin resistance) flanked by homology arms (~1 kb) specific to the regions upstream and downstream of the target gene cluster.

- Protopast Transformation: Co-transform the CRISPR/Cas9-sgRNA plasmid and the donor DNA into A. niger protoplasts.

- Selection and Screening: Select transformations on appropriate antibiotic media. Screen colonies via PCR to identify those with successful multi-copy gene deletions.

- Marker Recycling: Use the CRISPR/Cas9 system to excise the selectable marker, allowing for subsequent rounds of engineering.

- Protease Knockout: Repeat steps 1-5 to disrupt the gene for the major extracellular protease (PepA) to reduce target protein degradation.

- Chassis Validation: The resulting chassis strain (e.g., AnN2) is evaluated for reduced extracellular protein background and retained strong secretion machinery [40].

Protocol: Multi-Copy Gene Integration via RMCE inStreptomyces

This protocol describes the use of Recombinase-Mediated Cassette Exchange (RMCE) to integrate multiple copies of a Biosynthetic Gene Cluster (BGC) into a defined chromosomal locus of a Streptomyces chassis strain to enhance yield [41].

Principle: Utilize orthogonal tyrosine recombinase systems (Cre-lox, Vika-vox, Dre-rox) to precisely exchange a chromosomal landing pad with a plasmid-borne gene of interest, enabling multi-copy integration without recombining the plasmid backbone.

Materials:

- Chassis Strain: Engineered S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 with endogenous BGCs deleted and pre-engineered RMCE landing pads (e.g., loxP, vox, rox sites).

- E. coli Donor Strains: ET12567 (pUZ8002) or superior engineered strains (from Micro-HEP platform) for conjugation.

- RMCE Vectors: Modular cassettes containing the target BGC, an oriT for conjugation, and the corresponding recombination target sites (RTS).

- Recombinase Expression System: Plasmid or genome-integrated genes for the required recombinase (Cre, Vika, Dre).

Procedure:

- Vector Construction: Clone the target BGC into an RMCE vector containing the appropriate RTS (e.g., lox5171).

- Conjugal Transfer: Mobilize the constructed plasmid from the E. coli donor strain into the Streptomyces chassis via biparental conjugation.

- RMCE Induction: Induce the expression of the cognate recombinase (e.g., Cre for lox sites) to catalyze the cassette exchange between the plasmid and the chromosomal landing pad.

- Selection and Validation: Select for exconjugants where the target BGC has successfully replaced the landing pad's counter-selectable marker. Verify integration via PCR and Southern blotting.

- Multi-Copy Integration: Repeat the process using RTS with different spacer sequences (e.g., lox2272) to integrate additional copies of the BGC into other defined loci. The study showed that increasing the copy number of the xiamenmycin BGC from two to four led to a corresponding increase in final product yield [41].

Visualizing the Host Selection and Optimization Workflow

The diagram below outlines a logical workflow for selecting and optimizing a protein expression system based on protein characteristics and common experimental outcomes.

System Selection & Troubleshooting Workflow

The Scientist's Toolkit: Essential Research Reagents

This table lists key reagents, strains, and vectors used in advanced heterologous expression experiments, as cited in recent literature.

| Item | Function / Application | Example Use Case |

|---|---|---|

| SHuffle E. coli Strains [37] | Engineered for disulfide bond formation in the cytoplasm. | Production of proteins requiring multiple or complex disulfide bonds for activity. |

| Lemo21(DE3) E. coli Strain [37] | Tunable expression via rhamnose-controlled T7 lysozyme; ideal for toxic proteins. | Fine-tuning expression levels to balance yield and cell viability for toxic targets. |

| pMAL Vectors [37] | Protein fusion system using MBP (Maltose-Binding Protein) tag. | Enhances solubility of prone-to-aggregate proteins; allows purification via amylose resin. |

| Micro-HEP Platform E. coli Strains [41] | Engineered for superior stability of repeated sequences and conjugative transfer of large DNA. | Transferring large Biosynthetic Gene Clusters (BGCs) from E. coli to Streptomyces. |

| S. coelicolor A3(2)-2023 [41] | Optimized Streptomyces chassis with endogenous BGCs deleted and multiple RMCE sites. | Heterologous expression and yield improvement of natural products from cryptic BGCs. |

| Modular RMCE Cassettes (Cre-lox, Vika-vox) [41] | Enables precise, multi-copy, markerless integration of genes into specific genomic loci. | Stable, high-level expression of gene clusters in microbial chassis. |

| CRISPR/Cas9 System for A. niger [40] | Enables precise gene knockouts and integrations in the fungal genome. | Engineering chassis strains with reduced background secretion (e.g., AnN2 strain). |

| A. niger Chassis Strain AnN2 [40] | Low-background host with high-expression loci available for integration. | Rapid, high-yield production of diverse heterologous enzymes and biopharmaceuticals. |

# Troubleshooting Guide: FAQs on Promoter and Regulatory Systems

Question 1: Why is my recombinant protein not expressing at all inE. coli, even though the plasmid sequence is correct?

Answer: Non-expression in a validated system can stem from several issues, with protein toxicity and genetic sequence problems being the most common.

Protein Toxicity: If the recombinant protein disrupts the host's normal physiology, it can inhibit growth or cause cell death, preventing expression [42]. Common toxic proteins include ribonucleases, proteases, and membrane proteins.

- Solution: Use tightly regulated, low basal expression systems. Consider using specialized E. coli strains like C41(DE3) or C43(DE3) that are engineered for expressing toxic proteins [42]. Lowering the induction temperature and using a lower inducer concentration can also help reduce the metabolic burden.

Suboptimal Genetic Sequence: The DNA sequence itself may contain hidden features that hinder transcription or translation, even if the coding sequence is accurate [42].

- Solution:

- Codon Optimization: Redesign the gene sequence to use codons that are frequently used by the host organism, avoiding rare codons that can stall ribosomes [42].

- Check mRNA Secondary Structure: Use bioinformatics tools to analyze the 5' end of the mRNA for stable secondary structures that could prevent ribosome binding and translation initiation [42].

- Optimize the Translation Initiation Region (TIR): Ensure the Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) and the start codon context follow optimal sequences for high translation efficiency [42].

- Solution:

Question 2: My protein is expressed but forms inclusion bodies. How can I achieve soluble, functional protein?

Answer: Inclusion body formation is a frequent challenge, particularly with complex eukaryotic proteins or high-level expression in E. coli.

- Lower Expression Temperature: Shifting the growth temperature from 37°C to lower temperatures (e.g., 16-25°C) after induction can slow down protein synthesis, giving the protein more time to fold correctly [1].

- Use Fusion Tags: Fuse your target protein to a solubility-enhancing tag such as Maltose-Binding Protein (MBP), Glutathione S-transferase (GST), or SUMO. These tags can improve solubility and also aid in purification [1].

- Co-express Chaperones: Co-express molecular chaperones (e.g., GroEL-GroES, DnaK-DnaJ-GrpE) and foldases (e.g., protein disulfide isomerase) in the host strain. These auxiliary proteins assist in the proper folding of nascent peptides [1] [43].

- Modify Culture Conditions: Adjusting the medium composition, inducer concentration, and aeration can influence the folding environment within the cell [1].

Question 3: I am switching fromE. colito a Gram-positive host likeBacillus subtilis. Why is my vector unstable, and how can I improve protein yield?

Answer: Bacillus subtilis is an excellent protein secretion host but presents distinct challenges regarding vector stability and expression level.

Vector Instability: Many standard B. subtilis plasmid vectors undergo rolling-circle replication, generating single-stranded DNA intermediates that lead to plasmid loss during cell division [44].

- Solution:

- Use Integration Vectors: Stably integrate your expression cassette into the B. subtilis chromosome using homologous recombination. This eliminates plasmid instability issues [44].

- Employ Engineered Shuttle Vectors: Use advanced vectors like the iREX system, which controls RecA expression to prevent aberrant homologous recombination and improve DNA insert stability [44].

- Apply Essential Gene Complementation: Use a plasmid that carries an essential gene (e.g., floB) in a host strain where the endogenous copy is knocked out. This forces the cell to retain the plasmid for survival [44].

- Solution:

Low Protein Yield:

- Optimize Regulatory Elements: Replace the native promoter with a strong, inducible promoter specific for B. subtilis. Similarly, optimize the Ribosome Binding Site (RBS) strength and use an appropriate signal peptide for efficient secretion [44].

- Increase Gene Dosage: For plasmid-based systems, use vectors with a higher copy number origin of replication. For chromosomal integration, target the gene to a genetically stable, high-expression locus in the genome [44].

Question 4: How can I achieve high-level expression of a multi-subunit protein complex in a eukaryotic system?

Answer: The Baculovirus Expression Vector System (BEVS) in insect cells (e.g., Sf9, Sf21) is a powerful tool for this purpose.

- Choose the Right Cell Line: Sf9 cells are generally more robust, tolerant to high densities and shear stress, making them ideal for virus amplification and large-scale protein production. Sf21 cells are highly susceptible to infection and are excellent for initial virus titer determination via plaque assays [19].

- Utilize the MultiBac System: For expressing multi-subunit complexes, use the MultiBac system, which is specifically designed to accommodate and co-express multiple genes from a single baculovirus genome [19].

- Monitor Cell Health and Infection Parameters: The health of the insect cells at the time of infection is critical. Use cells in the mid-log phase of growth. Optimize the Multiplicity of Infection (MOI) and time of harvest post-infection (typically 48-72 hours) to maximize yield [19].

- Address Protein Degradation: Insect cells can produce proteases. If protein degradation is an issue, add protease inhibitors to the culture medium or try a different cell line like HighFive, though note that HighFive may also produce high protease levels [19].

# Performance Metrics of Standardized Regulatory Nodes

The table below summarizes the quantitative performance of five regulatory nodes standardized within the same plasmid backbone (SEVA standard) in E. coli, enabling direct comparison of their characteristics. This data helps in selecting the right system based on the required expression capacity, leakiness, and inducibility [45].

| Regulatory Node | Origin | Inducer | Mechanism | Key Performance Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LacI/P_trc [45] | E. coli | IPTG | Transcriptional Repressor | High capacity, but expression noise and basal levels are influenced by intracellular LacI levels. |

| XylS/P_m [45] | Pseudomonas putida | m-toluate (3-mBz) | Transcriptional Activator | Easier to standardize; can be activated by XylS overproduction even without effector. |

| AlkS/P_alkB [45] | Pseudomonas oleovorans | n-octane / DCPK | Transcriptional Activator (MalT family) | Requires ATP binding for activity; variant available that is free of catabolite repression. |

| CprK/P_DB3 [45] | Desulfitobacterium hafniense | CHPA | Transcriptional Activator (CRP/FNR family) | Binds to a specific "dehalobox" sequence in the promoter upon effector binding. |

| ChnR/P_chnB [45] | Acinetobacter sp. | cyclohexanone | Transcriptional Activator (AraC/XylS family) | Transcriptionally silent in the absence of the cognate inducer. |

Abbreviations: DCPK (Dicyclopropyl ketone); CHPA (3-chloro-4-hydroxyphenylacetic acid); 3-mBz (3-methylbenzoate).

# Experimental Protocols

Protocol 1: Assessing and Troubleshooting Non-Expression in E. coli T7 System

This protocol outlines a systematic approach to diagnose the root cause when no protein is expressed [42].

- Verify Plasmid Integrity: Isolate the plasmid from the expression strain and perform diagnostic restriction digestion or sequencing to confirm the correct insert and absence of mutations.

- Check Cell Growth Profile:

- Inoculate a small culture and grow to mid-log phase.

- Split the culture into induced and non-induced flasks.

- Monitor the optical density (OD600) over time. If growth is severely inhibited or arrested in the induced culture, it strongly indicates protein toxicity.

- Analyze Protein Expression:

- Take samples from both cultures before induction and at several time points after induction.

- Lyse the cells and analyze the total protein content by SDS-PAGE. The absence of a band at the expected molecular weight warrants further steps.

- Check mRNA Levels: Perform RT-PCR or quantitative PCR (qPCR) on RNA extracted from induced cells. If mRNA is detected, the problem is likely at the translation level. If no mRNA is present, the problem is transcriptional (e.g., promoter issue, toxic sequence causing silencing).

- Implement Solutions:

- If toxic: Switch to a more tightly controlled strain (e.g., C41/C43), use a weaker promoter, or lower induction temperature.

- If translational: Perform codon optimization and check the RBS and mRNA secondary structure.

Protocol 2: Refactoring a Gene Cluster with Modular Promoters in Streptomyces

This protocol describes how to replace native promoters in a biosynthetic gene cluster with well-characterized modular promoters to activate or enhance expression [46] [47].

- Cluster Cloning: Isolate the target gene cluster from the native host. This can be achieved using direct cloning methods like Cas9-Assisted Targeting of CHromosome segments (CATCH) [46].

- Vector Preparation: Use a modular toolkit vector (e.g., pPAB series) designed for flexibility in Streptomyces. The vector should contain yeast recombination sites and a marker for selection in S. cerevisiae [46].

- sgRNA Design and Cas9 Digestion: Design CRISPR guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting the promoter regions you wish to replace. Digest the cloned cluster plasmid with Cas9 protein complexed with the sgRNAs in vitro [46].

- Promoter Cassette Assembly:

- Design and synthesize double-stranded DNA fragments containing your chosen strong, constitutive promoters.

- Amplify these promoter cassettes and a yeast selection marker (e.g., URA) by PCR, adding 30-40 bp homology arms that match the sequences flanking the Cas9 cut sites in the target plasmid [46].

- Yeast Recombination:

- Co-transform the Cas9-linearized vector and the promoter cassette(s) into Saccharomyces cerevisiae.

- The yeast's highly efficient in vivo homologous recombination machinery will assemble the parts, inserting the new promoter into the target site [46].